Abstract

Purpose

Little evidence exists on the burden that chronic heart failure (HF) poses specifically to patients in China. The objective of this study, therefore, was to describe the burden of HF on patients in China.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional survey of cardiologists and their patients with HF was conducted. Patient record forms were completed by 150 cardiologists for 10 consecutive patients. Patients for whom a patient record form was completed were invited to complete a patient questionnaire.

Results

Most of the 933 patients (mean [SD] age 65.8 [10.2] years; 55% male; 80% retired) included in the study received care in tier 2 and 3 hospitals in large cities. Patients gave a median score of 4 on a scale from 1 (no disruption) to 10 (severe disruption) to describe how much HF disrupts their everyday life. Patients in paid employment (8%) missed 10% of work time and experienced 29% impairment in their ability to work due to HF in the previous week. All aspects of patients’ health-related quality of life (QoL) were negatively affected by their condition. Mean ± SD utility calculated by the 3-level 5-dimension EuroQol questionnaire was 0.8±0.2, and patients rated their health at 70.3 (11.5) on a 100 mm visual analog scale. Patients incurred costs associated with HF treatment, travel, and professional caregiving services.

Conclusion

HF is associated with poor health-related QoL and considerable disruption in patients’ lives. Novel and improved therapies are needed to reduce the burden of HF on patients and the health care system.

Keywords: patient burden, health-related quality of life, heart failure, survey, real-world

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) represents a major clinical and public health problem worldwide, affecting 40,000,000 people.1 In China, there are ~4,500,000 individuals with HF, equating to a prevalence of 0.9%.2

Multiple studies have demonstrated that HF has a negative impact on all aspects of patients’ physical, social, psychological, and emotional well-being.3,4 Patients with HF often experience difficulties in performing activities of daily living, suffer from economic, sexual, and psychosocial problems, and encounter troubles in social and professional relationships.5–7 These difficulties ultimately lead to impairment in patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL), maintenance of which may be as important as survival to patients living with a chronic, progressive illness, such as HF.7,8 Moreover, studies consistently demonstrate that poorer HRQoL correlates with increased hospitalization and death.9,10

Significant gaps exist in terms of evidence of the burden that HF poses, specifically to patients in China.11 Available evidence to date is drawn from small, single-center studies that may not represent the wider Chinese population with HF in real-world clinical practice.12,13 We conducted a cross-sectional survey of cardiologists and their patients with HF to estimate the burden of HF to patients in China.

Materials and methods

Study design

Data were drawn from the Adelphi HF Disease Specific Programme (DSP), a cross-sectional survey of cardiologists, their patients with HF, and those patients’ informal caregivers, conducted in a real-world setting in China in 2016. A DSP comprises 3 key phases: preparatory, data collection, and data processing/analysis.14 No formal validation procedure was undertaken; however, all numerical data were double entered.

Preparatory phase

Development of fieldwork materials

Four questionnaires were developed to inform the DSP – a physician survey, a patient record form (PRF), a patient self-completion questionnaire (PSC), and a caregiver self-completion questionnaire. The physician survey was used in face-to-face interviews with cardiologists. PRFs were completed by the cardiologist for their patients presenting with HF using data from medical records. PSCs were completed by the same patients, and caregiver self-completion questionnaires were completed by the informal caregivers of the patients (results gathered from the caregiver self-completion questionnaires have been reported by Jackson et al).15 The questionnaires were developed empirically, and their pharmacometric properties were not systematically assessed. The questionnaires were developed with input from experts in HF care; the concepts deemed most relevant to patients were selected empirically, and not as result of a formal process defining a conceptual framework, endpoint model and content validity, usually required to validate a patient-reported outcome measure (Ref FDA Guidance for Industry. Patient-reported outcomes measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims). The questionnaires were developed in English and then translated into Chinese by a local DSP fieldwork agency. A second independent UK-based translation agency verified the translated materials. Samples of the questionnaires are available on request.

Participant recruitment

Cardiologists were identified from public lists of health-care professionals, and were invited to participate in the DSP based on their eligibility in terms of: their speciality in cardiology; the year they qualified as a cardiologist (between 1974 and 2012); whether they worked in tier-2 (medium-sized, regional hospitals serving medium-sized cities) or tier-3 (large, municipal hospitals providing care at a national level) hospitals (if they worked in a hospital); whether they were personally responsible for treatment decisions; and the number of patients they saw in a typical week (in total and with HF, to ensure that they managed patients with HF on a regular basis; cardiologists who managed at least 16 patients with HF per month were eligible to participate). The first 150 cardiologists who met these criteria and agreed to participate in the study were enrolled.

Cardiologists were asked to complete PRFs for the next 10 patients they saw who presented with HF, immediately after their consultation. To ensure representativeness of HF patients with different phenotypes, a quota of 5 patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and 5 with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) was stipulated. An additional question in the survey specifically asked about the patient’s left ventricular ejection fraction values. Response to this question was used to stratify the patient as HFrEF or HFpEF. No other patient selection criteria were applied. Because participation by cardiologists was voluntary, the patient samples were not required to be representative of the Chinese population in terms of ethnicity, income, social class, or age. The same patients were invited to complete PSCs at the practice, independently of their cardiologist and immediately after their consultation. The data derived from the patient sample completing a PSC (n=933) corresponds to the main population assessed in this study. Included patients gave consent to participate.

Data-collection phase

Information on practice type was captured from the physician surveys. Information from the PRFs included: patient demographics; clinical characteristics; lifestyle; common symptoms of HF; and common side effects of HF treatment. Information from the PSCs included: demographics; lifestyle; common symptoms of HF and how troublesome they are; disruption of daily life due to HF; economic burden of HF; impact of HF on employment and HRQoL. Impact on employment was measured by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire, which is composed of 6 questions with the first one on employment status and the following ones referring to the past 7 days and assessing work time missed and work and activity impairment due to HF.16 The patient HRQoL was measured by the 3-level 5-dimension EuroQol questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L), which assesses mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. For each of these dimensions, the respondent is asked to indicate their level of difficulty, with response options being “no problems”, “some problems”, or extreme problems.17

All responses were anonymized to preserve participant confidentiality and avoid potential bias. The cardiologists could not see or influence the responses given by the patients or caregivers. The decision by a patient not to complete their respective questionnaire did not disqualify data recorded by the cardiologist on the PRF from being included in the analysis.

The questionnaire applied in this study followed the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association guidelines.18 The Code of Conduct states that within this context, ethical approval is not necessary, considering that the goal of research, rather than being to test a hypothesis is to improve understanding. The research was conducted in accordance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 and European equivalents.18,19

Data-processing/analysis phase

For the purposes of analysis and interpretation, HFrEF was defined as left ventricular ejection fraction <50% and HFpEF as ≥50%, according to Chinese guidelines.20 Basic descriptive statistics were derived using the software package QPSMR Reflect, version 2007.1 g (QPSMR Ltd, Wallingford, UK).

Results

Study population

The study comprised 150 cardiologists and 1,500 patients. Almost two-thirds (62%, n=933) of the patients for whom a PRF was completed also completed a PSC; this is the main population that this study focuses on.21

Cardiologist demographics

Of the 150 cardiologists, 91% worked only in a hospital; of these, 69% worked in tier-3 hospitals.

Patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics

Of the patients who completed a PSC (N=933), 55% of the patients were male, and their mean (SD) age was 65.8 (10.2) years (Table 1). Patients had a mean (SD) body mass index of 24.1 (3.1) kg/m2, 10% were current smokers, and 7% current consumers of alcohol (amount unspecified). Information on HF phenotype at the time of diagnosis was known by cardiologists for 88% of patients; 51% of patients were considered to have HFrEF (left ventricular ejection fraction <50%) and 37% to have HFpEF (left ventricular ejection fraction ≥50%). Information on New York Heart Association functional class of HF was available for all but 3 patients; at the time of consultation, 23% of patients were New York Heart Association class I, 48% class II, 25% class III, and 4% class IV. On average (SD), patients had been diagnosed with HF for 577 (795) days. The main causes of HF were hypertension (67%), coronary heart disease or myocardial infarction (44%), arrhythmia (25%), and diabetes (17%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics (N=933)

| Demographic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex (n=933) | |

| Male | 512 (55) |

| Female | 420 (45) |

| Age (years) (n=933) | |

| Mean (SD) | 65.8 (10.2) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (n=927) | |

| Mean (SD) | 24.1 (3.1) |

| Smoking status (n=933) | |

| Never smoked | 529 (57) |

| Ex-smoker | 285 (31) |

| Current smoker | 90 (10) |

| Unknown | 25 (3) |

| Alcohol consumption (n=933) | |

| Has never drunk alcohol | 561 (60) |

| Used to drink alcohol | 119 (13) |

| Drinks alcohol | 67 (7) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction at diagnosis (n=933) | |

| HFrEF (<50%) | 474 (51) |

| HFpEF (≥50%) | 343 (37) |

| New York Heart Association functional class (n=933) | |

| I | 217 (23) |

| II | 449 (48) |

| III | 230 (25) |

| IV | 34 (4) |

| Employment status (n=933) | |

| Retired/pensioner | 745 (80) |

| Working full time | 80 (9) |

| Homemaker | 54 (6) |

| Other | 25 (3) |

| Unemployed | 19 (2) |

| Don’t know | 8 (1) |

| Working part time | 1 (<1) |

| Student | 0 (0) |

| Days since diagnosis (n=919) | |

| Mean (SD) | 577 (795) |

| Top 5 underlying causes of HF (n=933) | |

| Hypertension | 621 (67) |

| Coronary heart disease/myocardial infarction | 410 (44) |

| Arrhythmia | 231 (25) |

| Diabetes | 159 (17) |

| High cholesterol | 134 (14) |

Notes: Values are presented as n (%) unless otherwise stated; percentages are calculated by including missing data and are subject to rounding. Data were obtained from patient record forms for patients who completed a patient self-completion questionnaire.

Abbreviations: HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Burden of HF on the patient

Common symptoms of HF

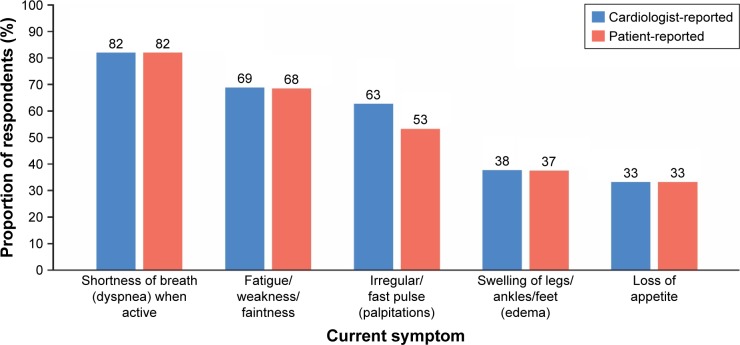

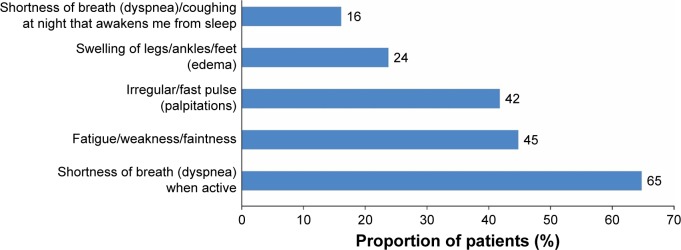

A matched analysis of cardiologist-versus patient-reported HF symptoms (n=933) was conducted. Patients (PSC) and cardiologists (PRF) were to select on a list of 17 symptoms, which were most troublesome for the patients, associated with HF. The most common symptoms reported by both groups were dyspnea when active, fatigue/weakness/faintness, palpitations, edema, and loss of appetite (Figure 1). The prevalence of these symptoms was aligned between patients and cardiologists, with the exception of palpitations, which patients reported less frequently than cardiologists (Figure 1). The symptoms reported to be the most troublesome by patients (n=924) correlated with those reported most frequently, with the exception of dyspnea/coughing at night that awakens the patient from sleep, which was frequently reported to be troublesome despite not being one of the most common symptoms (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

The 5 most common current symptoms of HF reported by patients and cardiologists (N=933 for both data sets).

Note: Data were obtained from patient record forms and patient self-completion questionnaires.

Abbreviation: HF, heart failure.

Figure 2.

The 5 most troublesome current symptoms of HF reported by patients (N=924).

Note: Data were obtained from patient self-completion questionnaires.

Abbreviation: HF, heart failure.

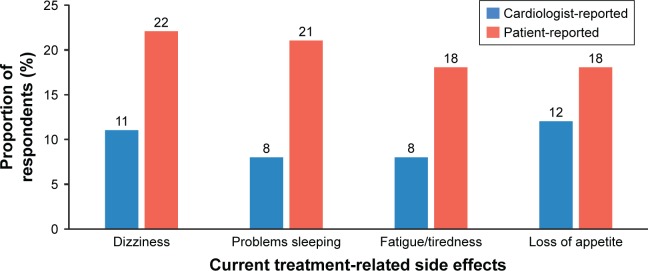

Common treatment-related side effects

A matched analysis of cardiologist-versus patient-reported treatment-related side effects (n=933) was conducted. The most common treatment-related side effects reported in both groups were loss of appetite, dizziness, problems sleeping, and fatigue/tiredness. Patients reported all of these side effects more frequently than cardiologists (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The 4 most common current side effects of HF treatment reported by patients and cardiologists (N=933 for both data sets).

Note: Data were obtained from patient record forms and patient self-completion questionnaires.

Abbreviation: HF, heart failure.

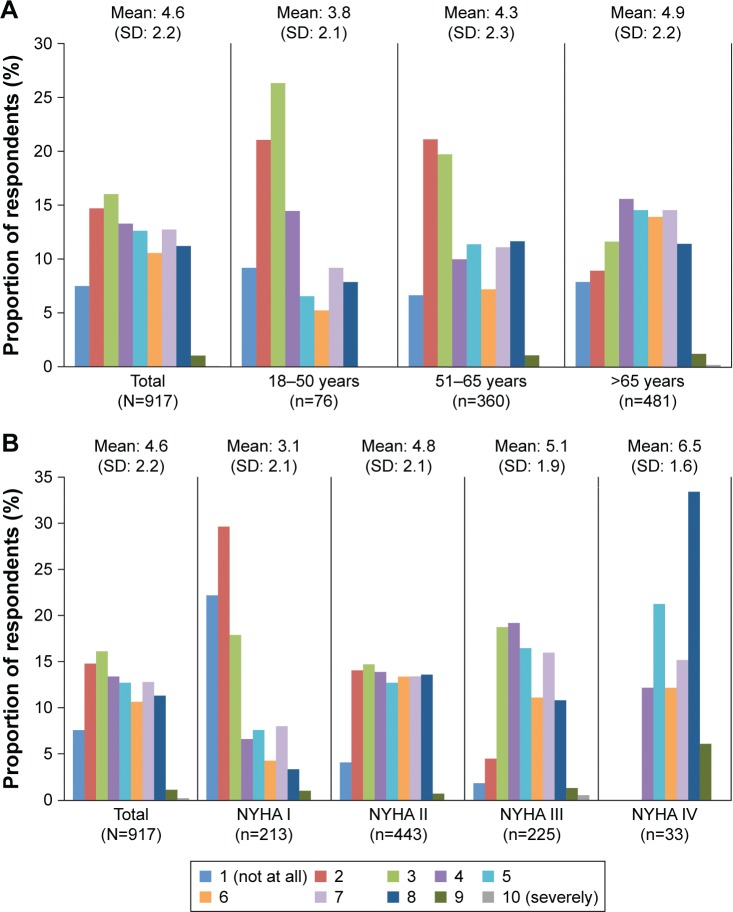

Disruption to daily life due to HF

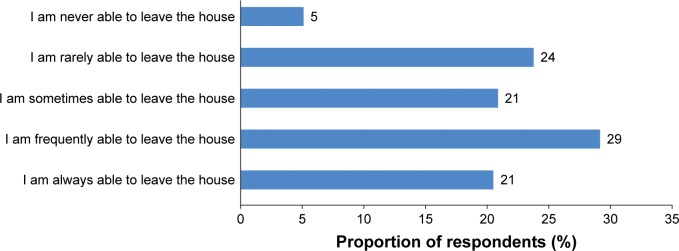

On a scale from 1 (not at all) to 10 (severely), patients (n=917) gave a median score (interquartile range) of 4.0 (3.0–7.0) to indicate how much HF disrupted their everyday life; this score increased with age (Figure 4). Only 1 in 5 patients (21%) reported that they were always able to leave the house, with almost one-third (29%) reporting that they were rarely or never able to leave the house due to HF (n=924; Figure 5).

Figure 4.

The level of disruption caused by HF on patients’ everyday life (N=917) stratified by (A) age and (B) New York Heart Association functional class.

Notes: Data were obtained from patient self-completion questionnaires. Presented from 1 “not at all” (no disruption) up to 10 “Severely” (highest disruption level).

Abbreviations: HF, heart failure; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Figure 5.

The impact of HF on patients’ ability to leave the house (N=924).

Note: Data were obtained from patient self-completion questionnaires.

Abbreviation: HF, heart failure.

Impact of HF on employment and activities outside of work

Most patients (80%) were retired, and a small proportion of patients (2%) were unemployed (Table 1). Of the patients who were unemployed (n=19), more than half (53%, n=10) were unemployed due to HF compared with just 2% (n=16) of those who were retired. In all, patients who had changed jobs or reduced their working hours at any time due to HF, 14% (n=89) reported that this had resulted in a drop in income. These patients reported a mean (SD) drop in income of 24% (17%) (n=55).

Based on patients’ responses to the WPAI questionnaire (n=924), 8% of patients were in paid employment at the time of study. These patients missed a mean (SD) of 10% (23%) of work time (n=56) and experienced a 29% (22%) impairment in their ability to work due to HF in the past 7 days (n=62). In addition, patients reported a 46% (23%) impairment in their ability to carry out daily activities outside of work (n=929).

Impact of HF on patients’ HRQoL

Patients’ responses to the EQ-5D-3L (n=931–933) suggested that the HRQoL of patients with HF was negatively affected across all domains (Table 2). The proportions of patients reporting a moderate or severe impact on HRQoL across the self-care, mobility, anxiety or depression, and usual activities domains was 21%, 24%, 28%, and 41%, respectively. Moreover, more than half (54%) of patients reported moderate or extreme pain or discomfort. Patients reported a mean (SD) utility score of 0.8 (0.2), and rated their health at 70.3 (11.5) on a 100 mm visual analog scale of the EQ-5D (EQ-5D VAS).

Table 2.

Responses of patients to the EQ-5D-3L (N=933)

| EQ-5D-3L domain | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mobility (N=933) | |

| I have no problems walking about | 708 (76) |

| I have some problems walking about | 214 (23) |

| I am confined to bed | 11 (1) |

| Self-care (n=931) | |

| I have no problems with self-care | 736 (79) |

| I have some problems with self-care | 171 (18) |

| I am unable to wash or dress myself | 24 (3) |

| Usual activities (n=933) | |

| I have no problems with performing my usual activities | 552 (59) |

| I have some problems with performing my usual activities | 333 (36) |

| I am unable to perform my usual activities | 48 (5) |

| Pain/discomfort (n=933) | |

| I have no pain or discomfort | 426 (46) |

| I have moderate pain or discomfort | 494 (53) |

| I have extreme pain or discomfort | 13 (1) |

| Anxiety/depression (n=933) | |

| I am not anxious or depressed | 675 (72) |

| I am moderately anxious or depressed | 247 (26) |

| I am extremely anxious or depressed | 11 (1) |

| Utility score (n=931) | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.2) |

| Visual analog scale (100 mm) (n=931) | |

| Mean (SD) | 70.3 (11.5) |

Notes: Values are presented as n (%) unless otherwise stated; percentages are calculated following the exclusion of missing data and are subject to rounding. Data were obtained from patient self-completion questionnaires.

Abbreviations: EQ-5D-3L, 3-level 5-dimension EuroQol questionnaire; Qol, quality of life.

Economic burden of HF on patients

Drug costs

Almost all (>99%) of the 887 patients who reported on their insurance plan were enrolled in an insurance scheme; of these, 99% had national insurance, and the remainder had commercial insurance. The full cost of HF-related drugs was covered for less than a quarter (24%) of these patients, while 51% and 31% paid a fixed amount or fixed percentage, respectively, for HF-related drugs. Patients paying a fixed amount for HF-related drugs (n=373) paid mean (SD) out-of-pocket costs of ¥255.00 (234.10) (USD $2.30 [2.11]) (at an exchange rate of ¥1: $0.01 on 12 June 2017) per month (Table 3). Patients paying a fixed percentage of the cost of HF-related drugs (n=231) paid mean(SD) out-of-pocket costs of 29% (17%) of the cost per month (Table 3).

Table 3.

HF-related costs incurred by patients

| Type of cost | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| HF-related drug costs | |

| For patients paying a fixed cost, per month (¥) (n=373) | 255.00 (234.10) |

| For patients paying a fixed percentage, per month (%) (n=231) | 29.1 (16.9) |

| Costs incurred during hospital visits | |

| Cost of transport, per hospital visit (¥) (n=789) | 24.30 (40.80) |

| Cost of food consumed during transport, per hospital visit (¥) (n=405) | 21.80 (40.70) |

| Professional caregiver costs, per month (¥) (n=57) | 1,701.00 (1,200.00) |

Notes: Data were obtained from patient self-completion questionnaires. Conversion rate to US dollars is exchange rate of ¥1: $0.01 on 12 June 2017.

Abbreviation: HF, heart failure.

Travel, food, and accommodation costs associated with hospital visits

Patients reported paying a mean (SD) of ¥24.30 (40.80) (USD $0.24 [0.41]) (at an exchange rate of ¥1: $0.01 on 12 June 2017) on transport per hospital visit (n=789), and a mean (SD) of ¥21.80 (40.70) (USD $0.22 [0.41]) (at an exchange rate of ¥1: $0.01 on 12 June 2017) on food consumed during the journey (n=405) (Table 3). Of the 901 patients who answered the question, most (97.9%) did not use overnight accommodation during their visit(s) to hospital.

Professional caregiver costs

A small proportion (9%, n=83) of patients were receiving assistance from a professional caregiver, paying a mean (SD) of ¥1,701.00 (1,200.00) per month (USD $17.01 [12]) (at an exchange rate of ¥1: $0.01 on 12 June 2017) for this service (n=57) (Table 3). Patients required assistance from a professional caregiver for a mean (SD) of 24.5 (19.3) hours per week (n=81).

Discussion

In order to truly understand the burden of HF in patients living with the condition, an accurate understanding of HF at the patient level is required. This survey assessed the burden of HF on patients from China, for which there is currently a large evidence gap.

In the current study, the typical patient with HF surveyed was a retired male of age 66 years – generally younger than the typical patient seen in studies in Western countries, who has a mean age of 67–70 years.22 Nevertheless, the burden of HF on patients included in this study was considerable; patients often experienced multiple, debilitating symptoms, the most troublesome of which were dyspnea when active, fatigue/weakness/faintness, and palpitations. Patients also reported treatment-related side effects, such as dizziness, loss of appetite, and problems sleeping. In the current study, cardiologists underestimated the frequency of these side effects by up to 13%; this suggests that some barriers exist in communication between patients and their physicians. HF negatively impacts patients’ ability to carry out activities of daily living.

HF had a considerable impact on patients’ ability to work and meant that patients who were in paid employment at the time of the study missed a mean of 10% of work time and experienced 29% impairment in their ability to work in the past 7 days. However, almost 4 in 5 patients were retired, likely due to the low retirement age in China rather than HF.23

The burden of HF felt by patients is reflected in an impact on patients’ HRQoL across all domains, as measured by the EQ-5D-3L. In particular, patients reported the greatest impact on their health status for the pain or discomfort domain, with more than half of individuals reporting moderate or extreme pain or discomfort. This demonstrates that greater effort needs to be made to improve patients’ pain relief. In addition, the current study found that 28% of patients reported being moderately or extremely anxious or depressed; this rate is generally higher than rates reported in previous studies of the general elderly population in China.24–28 For example, a meta-analysis conducted by Chen et al found that the prevalence of depression and depressive mood in patients in China aged ≥60 years was 3.86% and 14.8%, respectively.25 This meta-analysis included studies that used a range of methods to define depression, and so this comparison should be interpreted with caution. In the current study, the EQ-5D-3L generated a mean utility score of 0.8 and an EQ-5D VAS score of 70.3. These findings are in line with a recent study conducted by Zhu et al29 which reported a mean utility value of 0.7 and an EQ-5D VAS score of 66.8 for Chinese patients with HF treated in cardiology departments within tier-3 hospitals in 4 major cities in China. These findings suggest that HRQoL for patients with HF is lower than that observed for the general elderly (defined as either >60 or >65 years of age) population in China (utility score, 0.8–0.9; EQ-5D VAS score, 71.4).30,31 Finally, the EQ-5D-3L has just 1 question that assesses the emotional well-being of patients (“I am not/moderately/extremely anxious or depressed”), so this element of HRQoL may be under-represented.15,32

In the current study, almost all patients were enrolled in an insurance scheme; this is in line with universal health insurance coverage in China, which was achieved for >95% of the population in 2011.33 In addition, most patients were enrolled in a scheme that covered at least part of their HF-related drug costs; however, less than one-quarter of patients had insurance covering the full cost of their treatment. In those patients who were paying for their treatment, out-of-pocket costs attributed to HF-related drugs and traveling to the hospital were incurred. Larger costs were incurred by the small proportion of patients who were receiving assistance from a professional caregiver, for which they were paying a mean of ¥1,701 per month (USD $17.01) (at an exchange rate of ¥1: $0.01 on 12 June 2017). In the context of the minimum monthly wage in China, which varied from ¥1,270 to ¥2,190 (USD $12.7 to $21.9) (at an exchange rate of ¥1: $0.01 on 12 June 2017) in 2016,34 and a monthly gross domestic product per capita of ¥44,586 in 2017 (USD $446) (at an exchange rate of ¥1: $0.01 on 12 June 2017),35 these costs are considerable and likely to cause additional worry to those patients who are not in an accommodating financial situation.

The inevitable limitations associated with data collected from surveys are relevant for the current study, including recall bias, missing data, over-reporting of surveyed events and lack of representativeness to the overall HF population. Nevertheless, the Adelphi DSP is an established method for investigating real-world behavior and attitudes across a wide range of disease areas.36

The patient population included in the study were not required to be representative of the Chinese population in terms of ethnicity, income, social class, or age and caution should be taken to generalize the findings of this study to that of the whole population of patients with HF in China. This study represents a sample of consulting patients with HF who are treated in a cardiology setting, and not those managed in primary care or by other specialities, such as internal medicine or geriatricians. Only patients receiving care in tier-2 or -3 hospitals were included in the current study; these are more commonly found in large cities and, therefore, may not reflect caregivers of patients receiving care in tier-1 hospitals, which are usually found in rural areas. Furthermore, in the current study, the split of tier-2 and -3 hospitals was 31% and 69%, respectively, which does not reflect the split in the Chinese health care system (78% versus 21%).37

In addition, reporting bias may have been introduced because patients’ responses given during treatment by a cardiologist may have favored the specialist perspective. Nevertheless, in China, most patients with HF (~70%) initially consult a cardiologist; internists and family physicians play a less prominent role.21 In addition, cardiologists have an even greater role than internists and family physicians in confirming a diagnosis of HF (~82% of patients).21

Although cardiologists were requested to complete PRFs on a series of consecutive patients to avoid selection bias, formal source data verification (ie, checks against patient medical records) was not performed. Moreover, diagnosis in the target patient group is based primarily on the judgment and diagnostic skills of the respondent cardiologist rather than on a diagnostic checklist, although patients are managed in accordance with the same routine diagnostic procedures representative of that clinical practice setting. In this respect, the cardiologists’ responses are likely to reflect real-world data.

The selection of patients favors inclusion of those who consult more frequently, so patients with more severe disease or complications may be overrepresented in this sample. In addition, the inclusion criteria of this study required each cardiologist to recruit 10 patients, half of whom had HFrEF and the other half HFpEF. Because there is an equal distribution of HF phenotype in the general HF population in China,38–40 this would be unlikely to introduce bias.

Conclusion

This study contributes to increased understanding of the burden that HF imposes on patients from China, both from a humanistic and economic perspective. Patients included in this study had a considerable disruption in their HRQoL, and work productivity was impaired due to their condition. With an increase in the HF prevalence globally, a proper characterization of disease-specific impact in patients’ lives is important to develop new treatment strategies that may alleviate this burden for both patients and society.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Medical writing support was provided by Carly L Sellick of PharmaGenesis London, London, UK, and was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland.

Footnotes

Disclosure

James DS Jackson and Sarah E Cotton are employees of Adelphi Real World, and were contracted by Novartis to conduct this study. Sara Bruce Wirta is an employee of Novartis Sweden AB, Raquel Lahoz and Frederico J Calado are employees of Novartis Pharma AG, and Milun Zhang is an employee of Novartis Pharma China. Catia C Proenca is an employee of Wellmera AG contracted by Novartis Pharma AG. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu D, Huang G, Jiang H, et al. Investigation of prevalence and distributing feature of chronic heart failure in Chinese adult population. Chin J Cardiol. 2003;31(1):3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin RY, Levine RJ, Lin H. Adverse drug effects and angioedema hospitalizations in the United States from 2000 to 2009. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2013;34(1):65–71. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen HM, Clark AP, Tsai LM, Lin CC. Self-reported health-related quality of life and sleep disturbances in Taiwanese people with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(6):503–513. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181e15c37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallenborn J, Angermann CE. Depression and heart failure – a twofold hazard?: diagnosis, prognostic relevance and treatment of an underestimated comorbidity. Herz. 2016;41(8):741–754. doi: 10.1007/s00059-016-4483-8. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demir M, Unsar S. Assessment of quality of life and activities of daily living in Turkish patients with heart failure. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(6):607–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis EF, Johnson PA, Johnson W, Collins C, Griffin L, Stevenson LW. Preferences for quality of life or survival expressed by patients with heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20(9):1016–1024. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(01)00298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heo S, Lennie TA, Okoli C, Moser DK. Quality of life in patients with heart failure: ask the patients. Heart Lung. 2009;38(2):100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett SJ, Pressler ML, Hays L, Firestine LA, Huster GA. Psychosocial variables and hospitalization in persons with chronic heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 1997;12(4):4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstam V, Salem D, Pouleur H, et al. Baseline quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization in 5,025 patients with congestive heart failure. SOLVD investigations. Studies of left ventricular dysfunction investigators. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(8):890–895. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariely R, Evans K, Mills T. Heart failure in China: a review of the literature. Drugs. 2013;73(7):689–701. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang MX, Ruan XF, Xu Y. Effects of Kanlijian on exercise tolerance, quality of life, and frequency of heart failure aggravation in patients with chronic heart failure. Chin J Integr Med. 2006;12(2):94–100. doi: 10.1007/BF02857353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao JT, Ding J, Wang Z. The study of quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure. Xin Xue Guan Kang Fu Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2001;10:404–406. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: disease-specific programmes – a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–3072. doi: 10.1185/03007990802457040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson J, Cotton S, Bruce Wirta S, et al. Burden of heart failure on caregivers in China: results from a cross-sectional survey. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2018;12:1669–1678. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S148970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.EuroQol Group EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR) International Code of Marketing and Social Research Practice. 2007. [Accessed August 22, 2013]. Available from: http://www.icc.se/reklam/english/engresearch.

- 19.Department US of Health & Human Services [Accessed January 24, 2018];Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule, July 2013. Availble from: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chinese Society of Cardiology of the Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Board of the Chinese Journal of Cardiology Chinese heart failure diagnosis and treatment guidelines. 2014. [Accessed August 4, 2017]. Available from: http://www.cjcv.org.cn/xinxueguan20144202/33844.htm?locale=zh_CN.

- 21.Jackson J, Cotton S, Bruce Wirta S, et al. Care pathways and treatment patterns for patients with heart failure in China: results from a cross-sectional survey. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018 doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S166277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callender T, Woodward M, Roth G, et al. Heart failure care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(8):e1001699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.China Labour Bulletin China’s social security system. 2016. [Accessed August 4, 2017]. Available from: http://www.clb.org.hk/content/china%E2%80%99s-social-security-system.

- 24.Niti M, Ng TP, Kua EH, Ho RC, Tan CH. Depression and chronic medical illnesses in Asian older adults: the role of subjective health and functional status. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(11):1087–1094. doi: 10.1002/gps.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen R, Copeland JR, Wei L. A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies in depression of older people in the People’s Republic of China. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(10):821–830. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199910)14:10<821::aid-gps21>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen R, Wei L, Hu Z, Qin X, Copeland JR, Hemingway H. Depression in older people in rural China. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(17):2019–2025. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao S, Jin Y, Unverzagt FW, et al. Correlates of depressive symptoms in rural elderly Chinese. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1358–1366. doi: 10.1002/gps.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma X, Xiang YT, Li SR, et al. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of depression in an elderly population living with family members in Beijing, China. Psychol Med. 2008;38(12):1723–1730. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu S, Zhang M, Ni Q, et al. Indirect, direct non-medical cost and QoL by New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification in Chinese heart failure patients. Abstract presented at: ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress; October 31–November 6, 2016; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou T. Health related quality of life for general population in China: a systematic review. Chin Health Serv Manag. 2016;8:621–630. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun S, Chen J, Johannesson M, et al. Population health status in China: EQ-5D results, by age, sex and socio-economic status, from the National Health Services Survey 2008. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(3):309–320. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9762-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stromberg A, Bonner N, Grant L, et al. Psychometric validation of the Heart Failure Caregiver Questionnaire (HF-CQ®) Patient. 2017;10(5):579–592. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People’s Republic of China (MoHRSS) Year-end special edition: 2011 National Medical Insurance Work Summary. 2012. [Accessed August 4, 2017]. Available from: http://www.mohrss.gov.cn/SYrlzyhshbzb/dongtaixinwen/dfdt/gzdt/201201/t20120106_94504.html.

- 34.US-China Business Council (USCBC) Minimum wage rises in the cities, stalls in the provinces. China Business Review. 2017. [Accessed August 4, 2017]. Available from: http://www.chinabusinessreview.com/minimum-wage-rises-in-the-cities-stalls-in-the-provinces/

- 35.China GDP per capita, 1960–2017. [Accessed August 4, 2017]. Available from: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/china/gdp-per-capita.

- 36.Andersohn F, Walker J. Characteristics and external validity of the German Health Risk Institute (HRI) Database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(1):106–109. doi: 10.1002/pds.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) The number of national medical and health institutions as of the end of June 2016. [Accessed August 4, 2017]. Available from: http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/mohwsbwstjxxzx/s7967/201608/87343c7d63ce41ca8d8fddf7a5db66b7.shtml.

- 38.Collaborative Group on Survey of Heart Failure in Shanghai Cross-sectional survey on the current status of drug therapy in patients with stable heart failure in Shanghai. Chin J Cardiol. 2001;29:644–648. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shanghai Investigation Group of Heart Failure The evolving trends in the epidemiologic factors and treatment of hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure in Shanghai during the years of 1980, 1990 and 2000. Chin J Cardiol. 2002;30:24–26. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma JP, Wang L, Dang Q, et al. Retrospective analysis of drug treatment on inpatients with chronic heart failure. Chin J Epidemiol. 2007;28(1):78–82. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]