Abstract

Litchi (Litchi chinensis) is an important subtropical fruit tree with high commercial value. However, the short and centralized fruit maturation period of litchi cultivars represents a bottleneck for litchi production. Therefore, the development of novel cultivars with extremely early fruit maturation period is critical. Previously, we showed that the genotypes of extremely early-maturing (EEM), early-maturing (EM), and middle-to-late-maturing (MLM) cultivars at a specific locus SNP51 (substitution type C/T) were consistent with their respective genetic background at the whole-genome level; a homozygous C/C genotype at SNP51 systematically differentiated EEM cultivars from others. The litchi gene on which SNP51 was located was annotated as flavonol synthase (FLS), which catalyzes the formation of flavonols. Here, we further elucidate the variation of the FLS gene from L. chinensis (LcFLS) among EEM, EM, and MLM cultivars. EEM cultivars with a homozygous C/C genotype at SNP51 all contained the same 2,199-bp sequence of the LcFLS gene. For MLM cultivars with a homozygous T/T genotype at SNP51, the sequence lengths of the LcFLS gene were 2,202–2,222 bp. EM cultivars with heterozygous C/T genotypes at SNP51 contained two different alleles of the LcFLS gene: a 2,199-bp sequence identical to that in EEM cultivars and a 2,205-bp sequence identical to that in MLM cultivar ‘Heiye.’ Moreover, the coding regions of LcFLS genes of other MLM cultivars were almost identical to that of ‘Heiye.’ Therefore, the LcFLS gene coding region may be used as a source of diagnostic SNP markers to discriminate or identify genotypes with the EEM trait. The expression pattern of the LcFLS gene and accumulation pattern of flavonol from EEM, EM, and MLM cultivars were analyzed and compared using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for mature leaves, flower buds, and fruits, 15, 30, 45, and 60 days after anthesis. Flavonol content and LcFLS gene expression levels were positively correlated in all three cultivars: both decreased from the EEM to MLM cultivars, with moderate levels in the EM cultivars. LcFLS gene function could be further analyzed to elucidate its correlation with phenotype variation among litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods.

Keywords: Litchi chinensis Sonn., flavonol synthase (FLS), allelic diversity, fruit maturation period, extremely early-maturing trait, selection of cultivars

Introduction

Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.), a member of the family Sapindaceae, is an important subtropical fruit tree with high commercial value because of the excellent taste and rich nutritional value of its fruits (Li et al., 2013). China has a long history of litchi cultivation (more than 2,300 years), and abundant germplasm resources have been established (Wu, 1998). However, most litchi cultivars ripen between mid-June and mid-July. This results in a short and centralized fruit maturation period, which represents a bottleneck for litchi production in China (Li, 2008). Therefore, development of novel litchi cultivars with extremely early fruit maturation periods is critical for the industry.

The fruit maturation period of litchi is determined jointly by the flowering time and the fruit development process. The molecular mechanisms underlying the fruit maturation period of litchi are not yet fully understood; to our knowledge, there have been only two studies addressing this subject (Zhao et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2015). Zhao et al. (2011) detected five quantitative trait loci for the fruit maturation period using an F1 hybrid population from a cross of litchi cultivars: ‘Maguili’ × ‘Jiaohesanyuehong.’ Ding et al. (2015) showed that LcFT1 played an essential part in litchi floral induction, and that sequence differences in the LcFT1 promoter may be one of the causes of the natural variation in the flowering times of different litchi cultivars.

Previously, we surveyed the genetic relationships between 96 litchi accessions collected across China, using 90 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) evenly spaced across the litchi genome (Liu et al., 2015). The 96 litchi accessions could be classified into four main groups according to the fruit maturation period: extremely early-maturing (EEM), early-maturing (EM), middle-maturing, and late-maturing (Liu et al., 2015). Two clusters were detected among the 96 litchi accessions using STRUCTURE analysis. Accessions with the EEM trait were assigned to cluster 1, and accessions with the middle-to-late-maturing (MLM) trait were assigned to cluster 2. Accessions with the EM trait showed an almost equal percentage of admixture with each cluster (Liu et al., 2015). We further compared the genotypes of each SNP locus among these three groups. We identified a specific locus SNP51 (substitution type C/T), at which all six EEM cultivars were the only cultivars that showed a homozygous C/C genotype; all 75 except five MLM cultivars showed a homozygous T/T genotype, whereas all 15 except three EM cultivars showed a heterozygous C/T genotype. Therefore, the genotypes of litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods at the locus SNP51 seemed to be consistent with their respective genetic backgrounds on the whole-genome level, as identified by the previous STRUCTURE analysis (Liu et al., 2015). Litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods exhibited systematic variation in genotype at SNP51, and the homozygous C/C genotype at SNP51 could be used to systematically differentiate EEM cultivars from the other cultivars.

The gene on which SNP51 is located in litchi was annotated as flavonol synthase (FLS)1, which belongs to the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase subfamily. The first FLS gene was isolated from Petunia hybrida (Holton et al., 1993). More FLS genes were cloned and characterized from various plant species, including Arabidopsis thaliana (Pelletier et al., 1997; Owens et al., 2008; Preuss et al., 2009), Eustoma grandiflorum (Nielsen et al., 2002), Ginkgo biloba (Xu et al., 2012), and Vaccinium corymbosum (Zhang et al., 2016). FLS is an important enzyme in the flavonoid pathway that catalyzes the formation of flavonols. The flavonol pathway is an important downstream branch of the flavonoid pathway, as there is competition between FLS and dihydroflavonol 4-reductase for the common substrates dihydroflavonols, which leads to the biosynthesis of flavonols and anthocyanins (Davies et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2016). Flavonols are the most abundant subgroup of flavonoids and have important functions in plant growth and development, including regulation of auxin transport (Kuhn et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2011), modulation of leaf and flower color (Takahashi et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2015), and protection against ultraviolet-B irradiation (Bandurska et al., 2012; Majer et al., 2014).

In this study, we aimed to further elucidate the variation of the FLS gene from L. chinensis (LcFLS) among litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods. To this end, we cloned and characterized full-length cDNA and genomic DNA sequences of the LcFLS gene. We also examined the allelic diversity of the LcFLS gene among the EEM, EM, and MLM cultivars. In addition, the LcFLS gene expression patterns and flavonol content of the EEM, EM, and MLM cultivars were analyzed and compared using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), respectively. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an FLS from the family Sapindaceae.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Litchi cultivars grown in the National Litchi Germplasm Gene Bank in the Institute of Fruit Tree Research, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Guangzhou, China), were used in this study.

Genomic DNA and cDNA of the LcFLS gene were cloned from young leaves of an EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong’ and an MLM cultivar ‘Heiye.’ To explore the sequence variation of LcFLS gene sequence among cultivars with different fruit maturation periods, genomic DNA of the LcFLS gene was also cloned from young leaves of 27 other litchi cultivars (Table 1). A 10-year-old litchi tree with uniform vigor was selected for each cultivar, and young leaves were collected during the spring season of 2015.

Table 1.

Sequence lengths of the LcFLS gene and genotypes at SNP51 of 29 litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods.

| Number | Cultivar | Origin | Fruit maturation period | Genotype at SNP51 | Sequence length of LcFLS gene (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sanyuehong | Guangdong | Extremely early-maturing | C/C | 2199 |

| 2 | Yuhebao | Guangxi | Extremely early-maturing | C/C | 2199 |

| 3 | Hemaoli | Yunnan | Extremely early-maturing | C/C | 2199 |

| 4 | Yuanliyihao | Yunnan | Extremely early-maturing | C/C | 2199 |

| 5 | Yuanlierhao | Yunnan | Extremely early-maturing | C/C | 2199 |

| 6 | Yuanyangerhao | Yunnan | Extremely early-maturing | C/C | 2199 |

| 7 | Feizixiao | Guangdong | Early-maturing | C/T | 2199+2205 |

| 8 | Shuidong | Guangdong | Early-maturing | C/T | 2199+2205 |

| 9 | Dazao | Guangdong | Early-maturing | C/T | 2199+2205 |

| 10 | Baitangying | Guangdong | Early-maturing | C/T | 2199+2205 |

| 11 | Guangxitangbo | Guangxi | Early-maturing | C/T | 2199+2205 |

| 12 | Siyuehong | Guangxi | Early-maturing | C/T | 2199+2205 |

| 13 | Lanzhu | Fujian | Early-maturing | C/T | 2199+2205 |

| 14 | Dachenzi | Fujian | Early-maturing | C/T | 2199+2205 |

| 15 | Yuanhong | Fujian | Early-maturing | C/T | 2199+2205 |

| 16 | Heiye | Guangdong | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2205 |

| 17 | Lvhebao | Fujian | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2202 |

| 18 | Xinqiumili | Fujian | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2202 |

| 19 | Edanli | Hainan | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2206 |

| 20 | Nuomici | Guangdong | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2207 |

| 21 | Huaizhi | Guangdong | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2207 |

| 22 | Hongdenglong | Guangdong | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2207 |

| 23 | Jinzhong | Guangxi | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2207 |

| 24 | Xiafanzhi | Fujian | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2207 |

| 25 | Lingshanxiangli | Guangxi | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2211 |

| 26 | Wuheli | Hainan | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2211 |

| 27 | Maguili | Guangdong | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2219 |

| 28 | Huangpili | Hainan | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2221 |

| 29 | Jizuili | Guangxi | Middle-to-late-maturing | T/T | 2222 |

To compare the expression levels of the LcFLS gene and flavonol content among cultivars with different fruit maturation periods, the representative EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong,’ EM cultivar ‘Shuidong,’ and MLM cultivar ‘Nuomici’ were used. Mature leaves, flower buds, and fruits of the three cultivars were collected. Mature leaves were collected during the summer season of 2015. Flower buds were collected during the floral differentiation stage; the sampling dates were January 26, February 27, and March 18 of 2015 for ‘Sanyuehong,’ ‘Shuidong,’ and ‘Nuomici,’ respectively. Fruit samples were collected at four representative stages of development and maturation, 15, 30, 45, and 60 days after anthesis (DAA), respectively. Pericarp and seed were separated for fruits at 30 DAA. Pericarp, aril, and seed were separated for fruits at 45 and 60 DAA. Fruitlets at 15 DAA were used as a whole because separation was difficult at this stage. Three replications were set for each cultivar. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen upon collection and stored at -80°C until further use.

Cloning of the Full-Length cDNA and Genomic DNA of the LcFLS Gene

The LcFLS gene sequences were obtained from the litchi genome database (see foot note text 1). Primers were designed to isolate the LcFLS gene and explore its expression patterns (Table 2). Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaves of litchi cultivars using a modified CTAB method (Murray and Thompson, 1980). Total RNA was extracted from the fresh leaves using an RNAout 2.0 kit (Tiandz, China), and cDNA was synthesized with a PrimeScriptTM II 1st Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Takara, Japan). The genomic DNA and cDNA from leaves were used as templates to amplify the LcFLS gene from L. chinensis. PCR-amplified products were cloned into a pMD19-T vector (Takara, Japan), transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α, and then sequenced at the Beijing Genomics Institute (Beijing, China).

Table 2.

Primers for cloning and for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) assay of LcFLS gene.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Function |

|---|---|---|

| LcFLS-F | TAAAAACACTAGAGTGGCCTTGGC | Gene cloning |

| LcFLS-R | ATAGAATGTCTTTATTTTGGCACGG | Gene cloning |

| Q LcFLS-F | GCTACACAGAACCACCGTCA | qRT-PCR |

| Q LcFLS-R | TGGGAGGATTTTCAGGGTCA | qRT-PCR |

| Q LcActin-F | AGTTTGGTTGATGTGGGAGAC | qRT-PCR |

| Q LcActin-R | TGGCTGAACCCGAGATGAT | qRT-PCR |

Bioinformatic Analysis

LcFLS gene sequences were analyzed using online bioinformatics tools2,3. Multiple sequence alignments were performed with DNAMAN 8.04. The three-dimensional (3D) structure of LcFLS was built using the Web-based SWISS-MODEL server homology modeling pipeline. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 7.0 with the neighbor-joining method (Kumar et al., 2016). The reliability of the constructed trees was tested with a bootstrapping method using 1,000 replicates.

qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA from mature leaves, flower buds, and fruits of litchi cultivars were extracted using the RNAout 2.0 kit (Tiandz, China). Total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the aid of the PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit (Takara, Japan). Transcript levels of the LcFLS gene were analyzed using qRT-PCR with a CFX ConnectTM Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, United States) and SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II (Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific qRT-PCR primers were designed with Primer Express Software 3.0 (Applied Biosystems, United States) (Table 2). Gene expression values were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) and normalized using the LcActin gene (GenBank accession number HQ615689) as a reference. All reactions were performed in triplicate (with three biological replicates).

Determination of Flavonol Content

Harvested organs (mature leaves, flower buds, and fruits) were lyophilized for 48 h and ground into a fine powder. Powdered samples (100 mg) were extracted by adding 80% (v/v) methanol. The samples were then hydrolyzed by adding an equal volume of 2 N HCl, followed by incubation at 70°C for 40 min. During incubation, samples were vortexed every 10 min. After extraction, one volume of 100% (v/v) methanol was added, and the extracts were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm syringe filter and subjected to HPLC analysis. HPLC was performed with a C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; Sunfire, United States) using a Waters Alliance 2695 separation module. Methanol and double-distilled water were used as mobile phases A and B, respectively. The linear elution gradient method was used as follows: 0–5 min, 80% B; 5–30 min, 80% B; 30–40 min, 0% B. The flow rate was maintained at 1.0 mL/min. An injection volume of 10 μL and a wavelength of 368 nm were used for analysis. Quercetin was selected as the standard sample because it was the predominant flavonol in litchi tissue (Guo et al., 2008). Standard quercetin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (United States). The compounds in the sample were determined using a standard curve. All analyses were performed with three biological replicates.

Results

Identification of the Full-Length cDNA and Genomic DNA Sequences of the LcFLS Gene

The full-length cDNA sequence of the LcFLS gene amplified from the representative EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong’ was 1,079 bp long and contained a 1,008-bp open reading frame (ORF). The full-length genomic DNA of the LcFLS gene from ‘Sanyuehong’ was 2,199 bp long and had 100% identity with the coding region of the full-length cDNA sequence. Comparison of the cDNA sequence and the genomic DNA sequence indicated that there were three exons in the LcFLS gene, exon 1 (468 bp), exon 2 (327 bp), and exon 3 (213 bp), separated by two introns, intron 1 (459 bp) and intron 2 (661 bp).

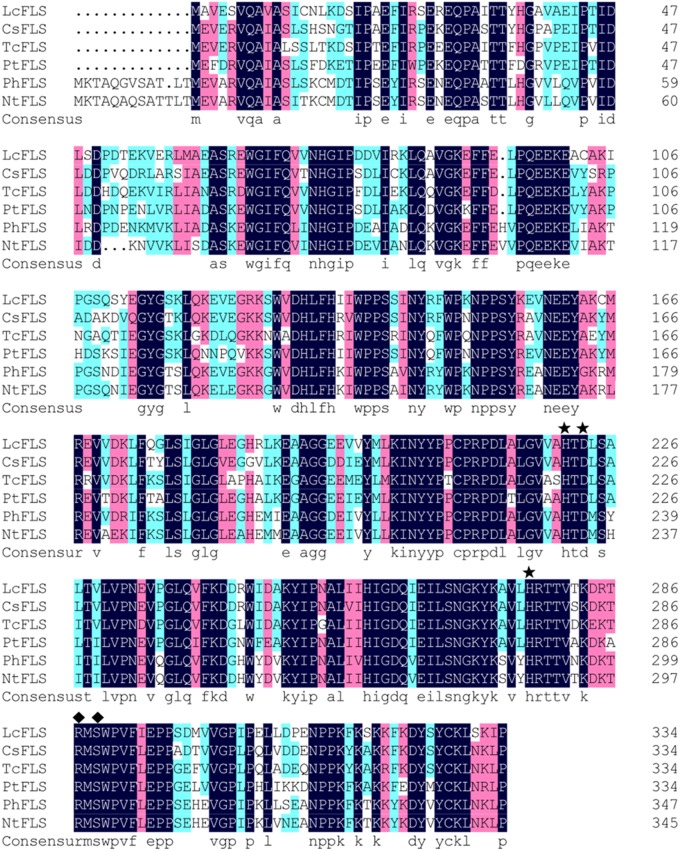

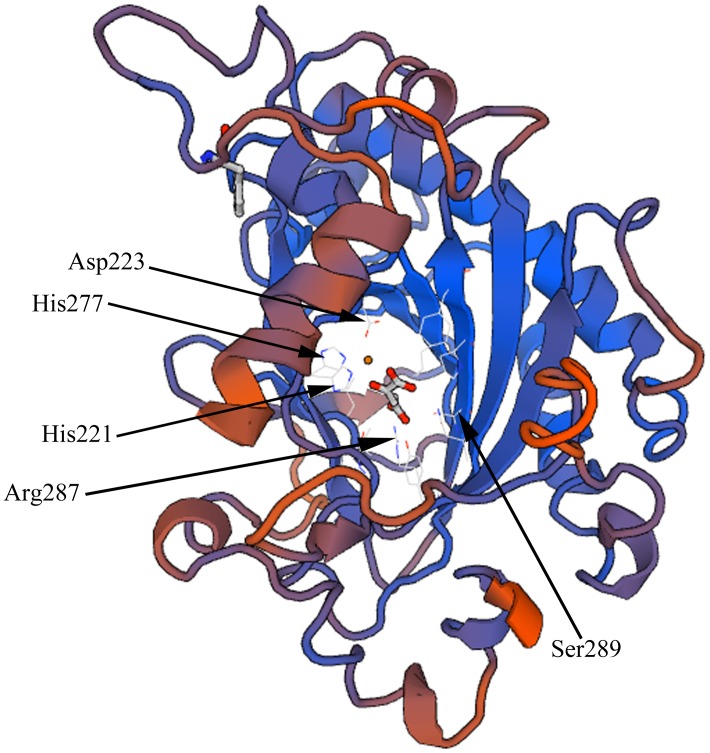

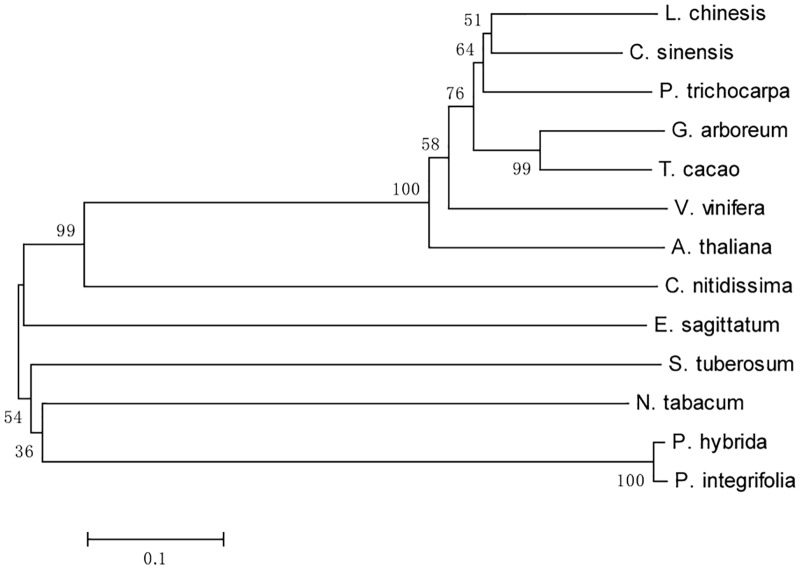

The deduced LcFLS protein contained 335 amino acids, with a calculated molecular weight of 37.88 kDa and an isoelectric point of 5.72. LcFLS had amino acid homology with the previously reported FLS proteins from Citrus sinensis (CsFLS, XP_006466183, 78%), Theobroma cacao (TcFLS, EOY09743, 74%), Populus trichocarpa (PtFLS, XP_002325697, 74%), P. hybrida (PhFLS, Q07512, 72%), and Nicotiana tabacum (NtFLS, NP_001312508, 70%) (Figure 1). A GenBank conserved domain database search revealed that LcFLS belongs to the 2OG-Fe(II) oxygenase superfamily, which is characterized by the presence of a conserved 2OG-FeII Oxy domain. The conserved sequence motifs of other members of the 2OG-FeII oxygenase superfamily, the H × D × nH motif for ligating ferrous iron (His221, Asp223, and His277) and the R × S motif participating in the 2-oxoglutarate binding (Arg287 and Ser289), were also found (Figure 1). The 3D structure of LcFLS was generated based on the crystal structure of the A. thaliana anthocyanidin synthase (AtANS; PDB ID 1gp5) (Wilmouth et al., 2002). The sequence similarity between LcFLS and the AtANS homologue was 45.18%, and the overall structures of LcFLS and AtANS were very similar (Figure 2). Notably, the conserved ferrous iron- and 2-oxoglutarate-binding sites that constitute the active site of LcFLS were found (Figure 2). Phylogenetic analysis of the LcFLS gene and 10 other FLS genes showed that the FLS gene of L. chinensis is closely related to that of C. sinensis (Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Sequence alignments of Litchi chinensis flavonol synthase (LcFLS) and flavonol synthase (FLS) proteins from Citrus sinensis (CsFLS), Theobroma cacao (TcFLS), Populus trichocarpa (PtFLS), Petunia hybrida (PhFLS), and Nicotiana tabacum (NtFLS); asterisks and diamonds indicate HXD and RXS motifs, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Three-dimensional structures of the deduced LcFLS protein; the conserved ferrous iron-binding sites at His221, Asp223, and His277, and 2-oxoglutarate-binding sites at Arg287 and Ser289 are indicated.

FIGURE 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of LcFLS and FLS proteins from selected species. Numbers at each interior branch indicate bootstrap support of 1,000 replicates. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: Solanum tuberosum (NP_001274926), Camellia nitidissima (ADZ28516), Vitis vinifera (BAE75808), Epimedium sagittatum (ABY63659), Gossypium arboreum (KHG18898), Citrus sinensis (XP_006466183), Theobroma cacao (EOY09743), Populus trichocarpa (XP_002325697), Petunia hybrid (Q07512), Nicotiana tabacum (NP_001312508), Arabidopsis thaliana (NP_196481), and Petunia integrifolia (ALQ80982).

Allelic Variation in the LcFLS Gene Among Litchi Cultivars With Different Fruit Maturation Periods

We amplified the cDNA and genomic DNA of the LcFLS gene from the representative MLM cultivar ‘Heiye.’ The full-length cDNA sequence of the LcFLS gene amplified from ‘Heiye’ was 1,079 bp long and contained a 1,008-bp ORF. The full-length genomic DNA of the LcFLS gene from ‘Heiye’ was 2,205 bp long and had 100% identity with the coding region of its full-length cDNA sequence.

A comparison of the 2,205 bp and 2,199 bp sequences of the LcFLS genes from ‘Heiye’ and ‘Sanyuehong’ showed only 95% identity. Researchers from the China Litchi and Longan Industry Technology Research System have completed the whole-genome sequencing of litchi cultivar ‘Feizixiao’ (an EM cultivar), assembled its highly heterozygous diploid genome into two haplotypes5, and identified pairs of allelic genes between the two haplotypes (unpublished data). The 2,199-bp and 2,205-bp sequences of the LcFLS genes from ‘Sanyuehong’ and ‘Heiye’ identified in our study were found to be two alleles on different haplotypes of a single gene (unpublished data).

To explore the allelic variation of LcFLS gene among litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods, full-length genomic DNA of the LcFLS genes from 27 other litchi cultivars was sequenced; the results are presented in Table 1. There were three main findings. (1) For the EEM cultivars with a homozygous C/C genotype at SNP51, the sequence length of the LcFLS gene was 2,199 bp, and all the sequences were identical to that of ‘Sanyuehong.’ (2) For the MLM cultivars with a homozygous T/T genotype at SNP51, the sequence length of the LcFLS gene ranged from 2,202 to 2,222 bp, and sequences with the same length were identical. The length variation was attributed mainly to the number variation of simple sequence repeat motif (AT)n in the first intron in LcFLS genes (Supplementary Figure S1). (3) All EM cultivars with a heterozygous C/T genotype at SNP51 contained two different alleles of the LcFLS gene: a 2,199-bp sequence identical to those in all EEM cultivars, and a 2,205-bp sequence identical to that in MLM cultivar ‘Heiye.’

A comparison of the full-length genomic DNA sequence of the LcFLS gene from other MLM cultivars with the ORF of the LcFLS gene from ‘Heiye’ showed that the sequences were almost identical, except for one non-synonymous SNP in each of exon 1 and exon 3, and two synonymous SNPs in exon 2 (Table 3). Therefore, the ORFs of the LcFLS gene in litchi cultivars could be divided into two types: the ORF of EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong’ and the ORF of MLM cultivar ‘Heiye.’ A comparison of the ORFs of the LcFLS genes of Sanyuehong’ and ‘Heiye’ gave 27 SNPs, including 16 synonymous and 11 non-synonymous SNPs (Figure 4). The 3D structure of LcFLS from ‘Heiye’ was similar to that of ‘Sanyuehong’ (result not shown).

Table 3.

Nucleotide diversity of the LcFLS gene open reading frame (ORF) for the middle-to-late-maturing (MLM) cultivar ‘Heiye’ (LcFLS-2205 bp) and other MLM cultivars (LcFLS-2,202 bp to 2,222 bp).

| LcFLS gene | Exon 1 | Exon 2 | Exon 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| LcFLS-2202bp | – | ACG-ACC (Thr-Thr) | – |

| LcFLS-2206bp | – | ACG-ACC (Thr-Thr) | GTG-ATG (Val-Met) |

| LcFLS-2207bp | – | ACG-ACC (Thr-Thr) | – |

| LcFLS-2211bp | TTT-TAT (Phe-Tyr) | ACG-ACC (Thr-Thr) | – |

| LcFLS-2219bp | TTT-TAT (Phe-Tyr) | ACG-ACC (Thr-Thr), GTG-GTA (Val-Val) | – |

| LcFLS-2221bp | TTT-TAT (Phe-Tyr) | ACG-ACC (Thr-Thr) | – |

| LcFLS-2222bp | TTT-TAT (Phe-Tyr) | ACG-ACC (Thr-Thr) | – |

FIGURE 4.

Sequence alignment between open reading frame (ORF) of extremely early-maturing (EEM) cultivar ‘Sanyuehong’ and middle-to-late-maturing (MLM) cultivar ‘Heiye.’

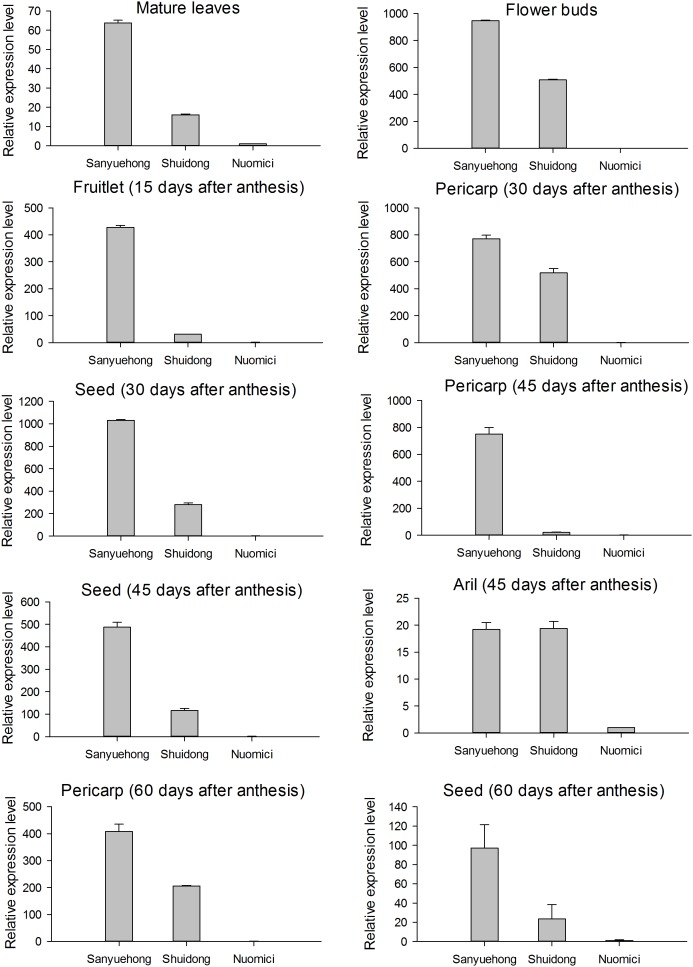

LcFLS Gene Expression Profiles in Litchi Cultivars With Different Fruit Maturation Periods

To compare the expression patterns of the LcFLS gene among litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods, the transcript levels of LcFLS genes in mature leaves, flower buds, and fruits of the EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong,’ EM cultivar ‘Shuidong,’ and MLM cultivar ‘Nuomici’ were analyzed using qRT-PCR (Supplementary Data Sheet S1). The transcript levels of the LcFLS gene were generally highest in ‘Sanyuehong,’ whereas they were lowest in ‘Nuomici’ (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Expression profile of the LcFLS gene among various tissues of EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong,’ early-maturing (EM) cultivar ‘Shuidong’ and MLM cultivar ‘Nuomici’; vertical bars represent the standard error of triplicate experiments.

In the mature leaves, LcFLS transcript levels were 63.8- and 16.1-fold higher in ‘Sanyuehong’ and ‘Shuidong,’ respectively, than in ‘Nuomici.’ The LcFLS gene transcript level in flower buds reached a 946.1- and 508.7-fold higher level in ‘Sanyuehong’ and ‘Shuidong,’ respectively, than in ‘Nuomici.’ In the fruitlets at 15 DAA, LcFLS transcript levels were 427.6- and 31.2-fold higher in ‘Sanyuehong’ and ‘Shuidong,’ respectively, than in ‘Nuomici.’ Pericarp and seed were separated for the fruits of 30 DAA; the expression levels of the LcFLS gene in these two tissues were 771.0- and 1031.1-fold higher in ‘Sanyuehong’ than in ‘Nuomici.’ In the fruits of 45 DAA, pericarp, aril, and seed were separated; the LcFLS gene showed the highest expression levels in pericarp and seed of ‘Sanyuehong’ and the lowest level in those of ‘Nuomici.’ In the case of aril, LcFLS mRNA levels were similar in ‘Sanyuehong’ and ‘Shuidong,’ and approximately 19-fold higher than in ‘Nuomici.’ For the pericarp of fruits at 60 DAA, LcFLS transcript levels were 407.9- and 205.6-fold higher in ‘Sanyuehong’ and ‘Shuidong,’ respectively, than that in ‘Nuomici.’ No LcFLS expression could be detected in the aril of fruits at 60 DAA.

Flavonol Content in Litchi Cultivars With Different Fruit Maturation Periods

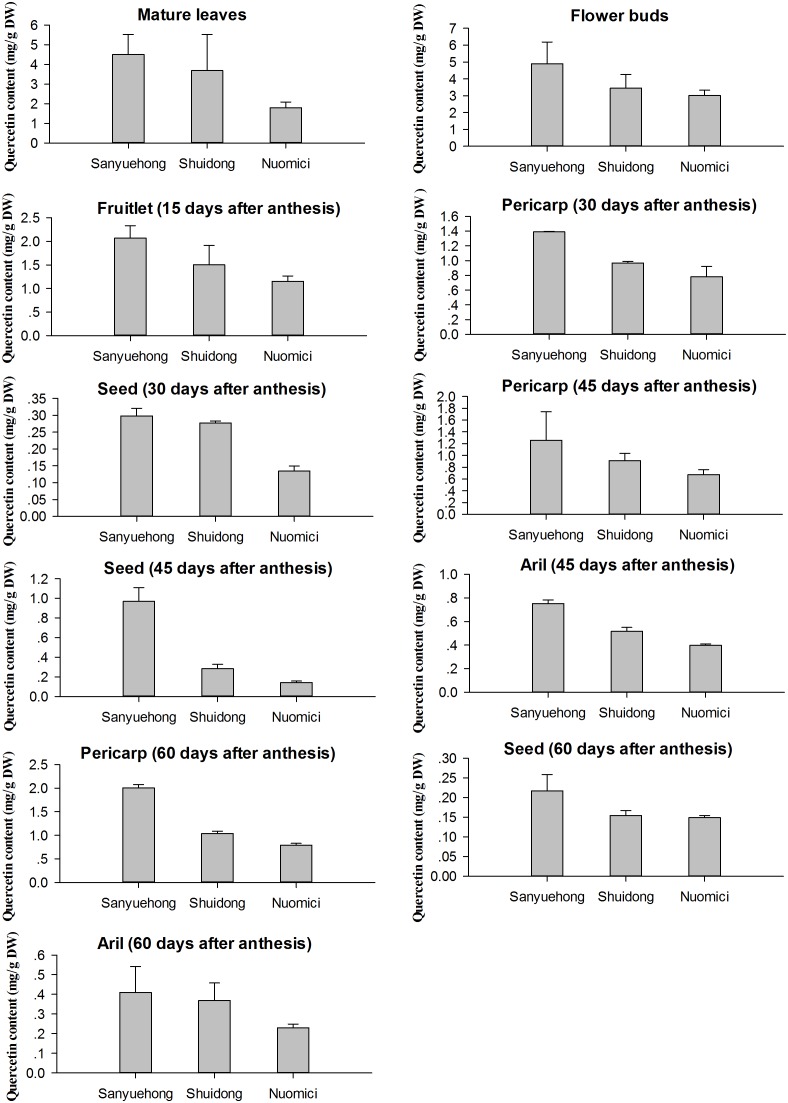

To further examine the correlation between flavonol content and LcFLS expression levels among litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods, the content of quercetin (a major type of flavonol in litchi tissue) was also measured for the EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong,’ EM cultivar ‘Shuidong,’ and MLM cultivar ‘Nuomici’ using HPLC analysis.

The correlation coefficient (R2) between different concentrations of quercetin standards and their peak areas was greater than 0.99, which indicated that the HPLC method developed in our study has good linearity. The profiles of quercetin standard samples are listed in Supplementary Figure S2. The quercetin content of various tissues of three litchi cultivars is shown in Figure 6. The quercetin content was highest in the EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong,’ with moderate levels in the EM cultivar ‘Shuidong’ and the lowest amounts in the MLM cultivar ‘Nuomici.’ The accumulation patterns of quercetin in the three litchi cultivars correlated well with the transcription patterns of the LcFLS gene.

FIGURE 6.

Quercetin content in various tissues of EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong,’ early-maturing (EM) cultivar ‘Shuidong,’ and MLM cultivar ‘Nuomici’; values are the means of three independent experiments, calculated as mg quercetin equivalent per 1 g dry weight (mg/g).

Discussion

Allelic Variation in the LcFLS Gene Among Litchi Cultivars With Different Fruit Maturation Periods

Owing to the long juvenile period of litchi, conventional natural breeding and cross-breeding are time-consuming. Predicting the fruit maturation period of individuals at an early stage, using molecular markers closely associated with the desirable trait, should reduce the space and labor investment and greatly accelerate the progress of litchi breeding trials. In our previous study, we found a perfect correlation between litchi phylogenetic relationships and the fruit maturation period, based on 90 SNPs evenly spaced across the litchi genome (Liu et al., 2015). We identified a specific locus SNP51 (substitution type C/T), genotypes at which of EEM cultivars (all C/C), EM cultivars (mostly C/T), and MLM cultivars (mostly T/T) seemed to be completely in accordance with their genetic background on the whole-genome level; moreover, the homozygous C/C genotype at SNP51 systematically differentiated EEM cultivars from others. In the present study, we further elucidated variation in the gene on which SNP51 is located – that is, FLS of litchi (LcFLS) – among the EEM, EM, and MLM cultivars. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an FLS from the family Sapindaceae.

The full-length genomic DNA sequences of the LcFLS gene from the EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong’ and MLM cultivar ‘Heiye’ were 2,199 bp and 2,205 bp long, respectively, and the two sequences were confirmed to correspond to two alleles on different haplotypes of a single gene (unpublished data). When we compared the allelic variation of LcFLS gene among 29 litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods (Table 1), we found that EEM cultivars with a homozygous C/C genotype at SNP51 all contained a 2,199-bp sequence of the LcFLS gene, the same as in ‘Sanyuehong.’ For the MLM cultivars with a homozygous T/T genotype at SNP51, the LcFLS gene length ranged from 2,202 to 2,222 bp; this length variation could be attributed mainly to the number variation of simple sequence repeat motif (AT)n in the first intron. Researchers from the China Litchi and Longan Industry Technology Research System have analyzed the genome sizes of 14 litchi accessions using flow cytometry and found significant variation in genome size, ranging from 550 to 620 Mb (unpublished data). Within-species variation in genome size among different accessions has been reported in various species (Biémont, 2008); this variation could be attributed to the different numbers of various repeated sequences, including satellite DNA (Ma and Jackson, 2006; Bosco et al., 2007). Our results suggested that addition and loss of satellite repeat elements might have contributed to the significant differences in genome size found among litchi accessions. All of the EM cultivars with a heterozygous C/T genotype at SNP51 contained two different alleles of LcFLS gene, a 2,199-bp sequence identical to that in all EEM cultivars and a 2,205-bp sequence identical to that in MLM cultivar ‘Heiye’. Furthermore, although the genomic DNA sequences of MLM cultivars varied greatly, their coding regions were almost identical to that of ‘Heiye.’ Therefore, there were two different types of ORF sequences of LcFLS genes among litchi cultivars, and these two ORF sequences contained 11 non-synonymous SNPs. Several active site residues have previously been identified, including Gly68 and Gly261, which are involved in proper folding of the FLS polypeptide (Wellmann et al., 2002), and H132, F134, K202, F293, and E295, which have roles in substrate binding of the FLS enzyme (Chua et al., 2008). Further studies are required to determine whether the 11 non-synonymous SNPs between the two different LcFLS ORFs lead to different catalytic activities of the FLS enzyme between litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods.

Based on comparison of the allelic variation of the LcFLS gene among EEM, EM, and MLM cultivars, we proposed that the coding region of the LcFLS gene represents a source of diagnostic SNP markers (such as SNP51) to discriminate or identify genotypes with the EEM trait in litchi. Liu (2001) analyzed the genetic relationships of 60 Chinese litchi accessions using 470 random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) loci and found that these accessions could be classified into three groups, which corresponded to the traits of EEM, EM, and late-to-extremely late-maturing. Liu (2001) identified 18 RAPD loci that were present only in EEM and EM cultivars, but absent in all late-to-extremely late-maturing cultivars. Huang (2005) subsequently converted one of the 18 RAPD loci to a sequence-characterized amplified region (SCAR) marker named SC-Em-J06-1360 and suggested that this marker could be used for early selection for breeding of litchi cultivars with EEM and EM traits. However, the 18 RAPD loci identified by Liu (2001) and the SCAR marker developed by Huang (2005) could not discriminate EEM cultivars from EM cultivars. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to identify a litchi gene and SNP marker that may be used for reliable and robust discrimination of EEM cultivars from others.

LcFLS Gene Expression Profile and Accumulation Pattern of Flavonol Among Litchi Cultivars With Different Fruit Maturation Periods

The expression pattern of the LcFLS gene and the accumulation pattern of flavonol (quercetin) from EEM, EM, and MLM cultivars were analyzed and compared using qRT-PCR and HPLC. We found positive correlations between flavonol (quercetin) content and LcFLS gene expression level among these three cultivars, indicating that the LcFLS gene encodes one of the key enzymes in the flavonol biosynthesis pathway of L. chinensis, which might be responsible for the formation of quercetin in L. chinensis. Positive correlations between flavonoid concentration and mRNA levels of FLS genes have also been reported in other plant species. For example, Moriguchi et al. (2002) isolated an FLS gene from Satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu Marc.), CitFLS, and found that increases in its transcript levels in fruit peel correlated with flavonol accumulation during fruit development. Fujita et al. (2006) obtained genomic sequences of FLS genes from Vitis vinifera ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (VvFLSs) and found that the accumulation pattern of quercetin coincided with the change in mRNA accumulation of the VvFLSs gene in the berry skins. Moreover, Xu et al. (2012) investigated tissue-specific and development-dependent transcript levels of the FLS gene of G. biloba (GbFLS) and found that the expression pattern of GbFLS correlated with the accumulation pattern of flavonols. Li et al. (2012) cloned and characterized an FLS gene from Fagopyrum tataricum (FtFLS), revealing an organ-specific expression pattern of the FtFLS gene that corresponded with trends in flavonoid content.

Among the three litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods, the transcript levels of the LcFLS gene and flavonol (quercetin) content both decreased from the EEM cultivar ‘Sanyuehong’ to the MLM cultivar ‘Nuomici,’ with moderate levels in the EM cultivar ‘Shuidong.’ In plants, flavonols are significantly involved in plant growth and development, and have been identified as the most active flavonoids, acting as regulators of polar auxin transport (Jacobs and Rubery, 1988; Buer et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2014). Reduction of quercetin content in FLS-silenced tobacco lines has been shown to increase polar auxin transport toward the root, decreasing the levels of auxin at apical region of shoots and thus leading to delayed flowering (Mahajan et al., 2011). In addition, flavonols usually act as co-pigments, affecting the color of many plant organs (Aida et al., 2000; Nielsen et al., 2002), and can also impart color by themselves (Middleton and Teramura, 1993). For example, overexpression of Camellia nitidissima FLS1 (CnFLS1) in tobacco altered the floral color to white or light yellow, and metabolic analysis indicated a significant increase in flavonol levels in transgenic plants, suggesting that CnFLS1 has a critical role in yellow color pigmentation (Zhou et al., 2013).

In litchi, the major distinguishing characteristic among the EEM, EM, and MLM cultivars is their fruit maturation period. EEM cultivars generally have earlier flowering dates and a shorter fruit development process (Li, 2008). Flavonols are known to be key regulators of auxin transport (Jacobs and Rubery, 1988; Buer et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2014), and auxin has been shown to have an important role in determining flowering time (Mahajan et al., 2011) and in the fruit development process (Mounet et al., 2012; Dare et al., 2013; El-Sharkawy et al., 2014). Thus, the flavonols might be involved in the differences in fruit maturation periods observed among litchi cultivars through the regulation of auxin transport. The color of flower buds is another distinguishing characteristic among the cultivars. EEM, EM, and MLM cultivar flower buds are dark brown, brown, and light-yellow, respectively (Liu, 2001); however, the mechanisms underlying this difference have never been explored. The decreasing flavonol content from EEM to EM and MLM cultivars might contribute to the gradually lightening color of their flower buds. Furthermore, there might be other characteristics among EEM, EM, and MLM litchi cultivars that have not yet been discovered. Therefore, future research should focus on functional analysis of the LcFLS gene and elucidation of its correlation with distinctive characteristics among litchi cultivars with different fruit maturation periods.

Author Contributions

WL and XX conceived and designed the study. ZX conducted the experiments. CF, NJ, and XM prepared the plant material and performed the analysis. WL, ZX, and XX wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read, reviewed, and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This study was granted by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31401829 and 31272135), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (No. 2014A030310467), and Guangdong Provincial Department of Science and Technology (No. 2017A070702005).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00567/full#supplementary-material

Sequence alignments of the first intron of LcFLS genes cloned from middle-to-late-maturing (MLM) cultivars.

The chromatogram of quercetin standard samples.(A) 0.005 mg/mL; (B) 0.01 mg/mL; (C) 0.02 mg/mL; (D) 0.04 mg/mL; and (E) 0.08 mg/mL.

Raw quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) data.

References

- Aida R., Yoshida K., Kondo T., Kishimoto S., Shibata M. (2000). Copigmentation gives bluer flowers on transgenic torenia plants with the antisense dihydroflavonol-4-reductase gene. Plant Sci. 160 49–56. 10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00364-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandurska H., Pietrowska-Borek M., Cieślak M. (2012). Response of barley seedlings to water deficit and enhanced UV-B irradiation acting alone and in combination. Acta Physiol. Plant. 34 161–171. 10.1007/s11738-011-0814-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biémont C. (2008). Genome size evolution: within-species variation in genome size. Heredity 101 297–298. 10.1038/hdy.2008.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco G., Campbell P., Leiva-Neto J. T., Markow T. A. (2007). Analysis of Drosophila species genome size and satellite DNA content reveals significant differences among strains as well as between species. Genetics 177 1277–1290. 10.1534/genetics.107.075069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buer C. S., Kordbacheh F., Truong T. T., Hocart C. H., Djordjevic M. A. (2013). Alteration of flavonoid accumulation patterns in transparent testa mutants disturbs auxin transport, gravity responses, and imparts long-term effects on root and shoot architecture. Planta 238 171–189. 10.1007/s00425-013-1883-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua C. S., Biermann D., Goo K. S., Sim T.-S. (2008). Elucidation of active site residues of Arabidopsis thaliana flavonol synthase provides a molecular platform for engineering flavonols. Phytochemistry 69 66–75. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dare A. P., Tomes S., Jones M., McGhie T. K., Stevenson D. E., Johnson R. A., et al. (2013). Phenotypic changes associated with RNA interference silencing of chalcone synthase in apple (Malus × domestica). Plant J. 74 398–410. 10.1111/tpj.12140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K. M., Schwinn K. E., Deroles S. C., Manson D. G., Lewis D. H., Bloor S. J., et al. (2003). Enhancing anthocyanin production by altering competition for substrate between flavonol synthase and dihydroflavonol 4-reductase. Euphytica 131 259–268. 10.1023/A:1024018729349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding F., Zhang S. W., Chen H. B., Su Z. X., Zhang R., Xiao Q. S., et al. (2015). Promoter difference of LcFT1 is a leading cause of natural variation of flowering timing in different litchi cultivars (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Plant Sci. 241 128–137. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sharkawy I., Sherif S. M., Jones B., Mila I., Kumar P. P., Bouzayen M., et al. (2014). TIR1-like auxin-receptors are involved in the regulation of plum fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 65 5205–5215. 10.1093/jxb/eru279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita A., Goto-Yamamoto N., Aramaki I., Hashizume K. (2006). Organ-specific transcription of putative flavonol synthase genes of grapevine and effects of plant hormones and shading on flavonol biosynthesis in grape berry skins. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 70 632–638. 10.1271/bbb.70.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C. J., Xu J., Wei J. Y., Yang J. J., Wu J. Q. (2008). The flavonoid content of common fruits in China. Acta Nutr. Sin. 30 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Holton T. A., Brugliera F., Tanaka Y. (1993). Cloning and expression of flavonol synthase from Petunia hybrida. Plant J. 4 1003–1010. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1993.04061003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T. L. (2005). Molecular Marker Analysis of Two Important Traits of Litchi chinensis Sonn and Genetic Linkage Map Construction of Dimocarpus longan Lour. Ph.D. dissertation, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M., Rubery P. H. (1988). Naturally occurring auxin transport regulators. Science 241 346–349. 10.1126/science.241.4863.346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn B. M., Geisler M., Bigler L., Ringli C. (2011). Flavonols accumulate asymmetrically and affect auxin aransport in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 156 585–595. 10.1104/pp.111.175976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. R., Ramirez M. V., Miller N. D., Vallabhaneni P., Ray W. K., Helm R. F., et al. (2011). Auxin and ethylene induce flavonol accumulation through distinct transcriptional networks. Plant Physiol. 156 144–164. 10.1104/pp.111.172502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. L., Bai Y. C., Li S. J., Chen H., Han X. Y., Zhao H. X., et al. (2012). Cloning, characterization, and activity analysis of a flavonol synthase gene FtFLS1 and its association with flavonoid content in tartary buckwheat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60 5161–5168. 10.1021/jf205192q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. Q., Wang Y., Huang X. M., Li J., Wang H. C., Li J. G. (2013). De novo assembly and characterization of fruit transcriptome in Litchi chinensis Sonn and analysis of differentially regulated genes in fruit in response to shading. BMC Genomics 14:552. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. G. (2008). The litchi. Beijing: China Agriculture Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. M. (2001). Construction of Genetic Linkage Map and Analysis of Germplasm Resources of Litchi chinensis Soon. Ph.D. dissertation, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Xiao Z. D., Bao X. L., Yang X. Y., Fang J., Xiang X. (2015). Identifying litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) cultivars and their genetic relationships using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers. PLoS One 10:e0135390. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCt method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo P., Ning G., Wang Z., Shen Y., Jin H., Li P., et al. (2016). Disequilibrium of flavonol synthase and dihydroflavonol-4-reductase expression associated tightly to white vs. red color flower formation in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1257. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Jackson S. A. (2006). Retrotransposon accumulation and satellite amplification mediated by segmental duplication facilitate centromere expansion in rice. Genome Res. 16 251–259. 10.1101/gr.4583106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan M., Ahuja P. S., Yadav S. K. (2011). Post-transcriptional silencing of flavonol synthase mRNA in tobacco leads to fruits with arrested seed set. PLoS One 6:e28315. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majer P., Neugart S., Krumbein A., Schreiner M., Hideg É. (2014). Singlet oxygen scavenging by leaf flavonoids contributes to sunlight acclimation in Tilia platyphyllos. Environ. Exp. Bot. 100 1–9. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton E. M., Teramura A. H. (1993). The role of flavonol glycosides and carotenoids in protecting soybean from ultraviolet-B damage. Plant Physiol. 103 741–752. 10.1104/pp.103.3.741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi T., Kita M., Ogawa K., Tomono Y., Endo T., Omura M. (2002). Flavonol synthase gene expression during citrus fruit development. Physiol. Plant. 114 251–258. 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1140211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounet F., Moing A., Kowalczyk M., Rohrmann J., Petit J., Garcia V., et al. (2012). Down-regulation of a single auxin efflux transport protein in tomato induces precocious fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 63 4901–4917. 10.1093/jxb/ers167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. G., Thompson W. F. (1980). Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8 4321–4326. 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K., Deroles S. C., Markham K. R., Bradley M. J., Podivinsky E., Manson D. (2002). Antisense flavonol synthase alters copigmentation and flower color in lisianthus. Mol. Breed. 9 217–229. 10.1023/a:1020320809654 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owens D. K., Alerding A. B., Crosby K. C., Bandara A. B., Westwood J. H., Winkel B. S. J. (2008). Functional analysis of a predicted flavonol synthase gene family in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 147 1046–1061. 10.1104/pp.108.117457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier M. K., Murrell J. R., Shirley B. W. (1997). Characterization of flavonol synthase and leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase genes in Arabidopsis. Further evidence for differential regulation of “early” and “late” genes. Plant Physiol. 113 1437–1445. 10.1104/pp.113.4.1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss A., Stracke R., Weisshaar B., Hillebrecht A., Matern U., Martens S. (2009). Arabidopsis thaliana expresses a second functional flavonol synthase. FEBS Lett. 583 1981–1986. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R., Githiri S. M., Hatayama K., Dubouzet E. G., Shimada N., Aoki T., et al. (2007). A single-base deletion in soybean flavonol synthase gene is associated with magenta flower color. Plant Mol. Biol. 63 125–135. 10.1007/s11103-006-9077-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J., Han Z., Zhang J., Hu Y., Song T., Yao Y. (2015). The balance of expression of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase and flavonol synthase regulates flavonoid biosynthesis and red foliage coloration in crabapples. Sci. Rep. 5:12228. 10.1038/srep12228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellmann F., Lukacin R., Moriguchi T., Britsch L., Schiltz E., Matern U. (2002). Functional expression and mutational analysis of flavonol synthase from Citrus unshiu. Eur. J. Biochem. 269 4134–4142. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmouth R. C., Turnbull J. J., Welford R. W. D., Clifton I. J., Prescott A. G., et al. (2002). Structure and mechanism of anthocyanidin synthase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Structure 10 93–103. 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00695-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. X. (1998). Encyclopedia of China fruits. Beijing: China Forestry Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu F., Li L. L., Zhang W. W., Cheng H., Sun N. N., Cheng S. Y., et al. (2012). Isolation, characterization, and function analysis of a flavonol synthase gene from Ginkgo biloba. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39 2285–2296. 10.1007/s11033-011-0978-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R., Han K., Heller W., Albert A., Dobrev P. I., Zažímalová E., et al. (2014). Kaempferol 3-O-rhamnoside-7-O-rhamnoside is an endogenous flavonol inhibitor of polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis shoots. New Phytol. 201 466–475. 10.1111/nph.12558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. Y., Liu H. C., Jia C. G., Liu Y. J., Wang F. T., Wang J. Y. (2016). Cloning, characterization and functional analysis of a flavonol synthase from Vaccinium corymbosum. Trees 30 1595–1605. 10.1007/s00468-016-1393-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. H., Guo Y. S., Fu J. X., Huang S. S., Lu B. B., Zhou J., et al. (2011). Molecular genetic map construction and QTL analysis for fruit maturation period in litchi. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 25 2315–2320. 10.5504/bbeq.2011.0046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. W., Fan Z. Q., Chen Y., Zhu Y. L., Li J. Y., Yin H. F. (2013). Functional analyses of a flavonol synthase-like gene from Camellia nitidissima reveal its roles in flavonoid metabolism during floral pigmentation. J. Biosci. 38 593–604. 10.1007/s12038-013-9339-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequence alignments of the first intron of LcFLS genes cloned from middle-to-late-maturing (MLM) cultivars.

The chromatogram of quercetin standard samples.(A) 0.005 mg/mL; (B) 0.01 mg/mL; (C) 0.02 mg/mL; (D) 0.04 mg/mL; and (E) 0.08 mg/mL.

Raw quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) data.