Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to provide recommendations on initiating and maintaining long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) in individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder.

Methods

A 50-question survey comprising 916 response options was completed by 34 expert researchers and high prescribers with extensive LAI experience, rating relative appropriateness/importance on a 9-point scale. Consensus was determined using chi-square test of score distributions. Results of 21 questions comprising 339 response options regarding LAI initiation, maintenance treatment, adequate trial definition, identifying treatment nonresponse, and switching are reported.

Results

Experts agreed that the most important LAI selection factor was patient response/tolerability to previous antipsychotics. An adequate therapeutic LAI trial was defined as the time to steady state ± 1–2 injection cycles. Experts suggested that oral efficacy and tolerability should be established before switching to an LAI, without consensus on the required time, and that the time for oral supplementation and next injection interval should be determined by the time to attainment of therapeutic LAI levels. Most experts agreed that ≥1 adequate LAI trial is needed to identify the lack of efficacy. There was little agreement about strategies for switching between LAIs.

Conclusion

Expert guidance may aid clinicians in their decisions regarding initiating/maintaining LAIs in individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder.

Keywords: expert consensus, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, long-acting injectable antipsychotics

Introduction

In individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) have been shown to be beneficial in preventing relapse.1 An important issue in these individuals is poor medication adherence, which can negatively affect clinical outcomes. In bipolar disorder, poor adherence is associated with mood relapses (particularly depressive episodes), an increased risk of hospitalization and emergency room visits, and increased employee costs due to greater absenteeism, short-term disability, and workers’ compensation.2 Similar consequences are associated with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder because of relapse resulting from poor adherence.3 Some of the factors that may contribute to reduced adherence include side effects (perceived or actual), poor efficacy, lack of social support, cognitive deficits, complexity of treatment regimens, religious or cultural beliefs, limited insight into need for treatment, substance use disorder, treatment access or cost issues, inadequate or lack of health insurance, and an unstable living environment.4,5

Although currently underutilized in comparison with oral antipsychotics, LAIs can be an important treatment option for addressing the high rates of poor adherence to medication in individuals with serious mental illness.6–11 LAIs possess several important features that may help improve adherence in individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder, including elimination of the need for daily administration, enabling health care providers (HCPs) to be alerted and intervene if the LAI is not taken, and a guarantee of administration and transparency of adherence. When an individual is being administered an LAI and relapse does occur, the HCP knows that relapse is due to a reason other than nonadherence.9 Importantly, LAIs may reduce the risk of relapse and hospitalization, which can affect health outcomes, quality of life, and health care costs.12 Although meta-analyses of early randomized controlled trial data failed to show consistent superiority of LAIs over oral antipsychotics with regard to relapse prevention, hospitalization, or secondary outcomes,13 these studies often did not adequately represent real-world practice.12,14 Subsequent analyses of LAI mirror image studies12 and cohort studies,15 which may better represent real-world individuals and more typical practice settings, suggested that LAIs may be superior to oral antipsychotics in preventing hospitalization in patients with schizophrenia.12

Although LAIs appear to be a potentially useful element of the treatment armamentarium for schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder based on these data, there is a lack of published evidence and treatment guidelines on optimal strategies for the initiation and maintenance of treatment with LAIs, which would at least partly explain why LAIs remain underutilized.2,16–18 Most guidelines in the US support atypical LAIs as an effective option for managing nonadherence; however, recommendations for LAI use are not standardized. Expert consensus guidelines supported by the French Association for Biological Psychiatry and Neuropsychopharmacology (AFPBN) suggest that psychiatrists should inform patients about LAIs and offer an LAI as a first-line treatment to most individuals who require long-term antipsychotic treatment.18 In contrast, the American Psychiatric Association guidelines recommend these agents for use only in the case of recurrent relapses due to nonadherence or in individuals who would prefer an LAI.17 Guidelines from the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments recommend the LAI, risperidone, as first-line maintenance monotherapy in addition to other antipsychotics in bipolar disorder as well as an adjunctive therapy with lithium or divalproex.2 A more recent systemic review and expert consensus for LAIs in bipolar disorder recommended using an LAI in individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar I disorder, rapid cycling bipolar disorder, and bipolar-type schizoaffective disorder.16 This report also recommends use of LAIs in individuals with bipolar disorder at risk for or demonstrating poor adherence and multiple episodes, infrequent but serious episodes, residual symptoms while taking multiple oral agents, or a preference for an LAI over oral medications.16

Given the lack of supporting clinical trial data, inadequate evidence base, and overall low use of LAIs despite indications of compelling advantages with respect to adherence and other outcomes, additional guidance on the use of LAIs is needed to address gaps in the literature and inform their appropriate use in individuals with serious mental illness.

Aims of the study

To address gaps in knowledge regarding appropriate LAI use, an expert consensus survey of US experts was conducted to obtain recommendations on the clinical use of LAIs in individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective and bipolar disorders. A companion paper has been developed providing expert guidance on identifying appropriate individuals for LAI prescribing, potential barriers to LAI use, and potential facilitators that would help HCPs decide to administer an LAI.48 The purpose of this analysis of the expert consensus survey was to provide guidance on initiation and maintenance treatment with LAIs in individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective and bipolar disorders.

Materials and methods

This expert consensus survey assessed the relative appropriateness of LAI treatment for several patient characteristics and clinical scenarios as well as optimal prescribing practices for initiation and continuation/maintenance treatment with LAIs. For the purpose of this survey, LAIs were considered as one group, and a distinction between typical and atypical antipsychotics was not made. The survey was administered online via SurveyMonkey® (SurveyMonkey Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) between April and November 2016 and contained 50 questions (a total of 916 response options). Respondents’ opinions and practices regarding LAI prescribing for individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective and bipolar disorders were elicited from the experts surveyed. In line with the patient assessment and clinical decision-making process, the survey consisted of three overarching and sequential sections: 1) identifying patients, 2) initiation of therapy, and 3) maintenance treatment.

A 9-point scale adapted from the RAND method19 was used by survey respondents to rate predefined options with some questions including a write-in or comment option. The rating scale ranged from 1 to 9: 1 represented the least appropriate or worst option and 9 represented the most appropriate or best option. The exact wording of the worst to best terminology was slightly modified depending on a question’s context (ie, 1 indicated extremely inappropriate, strongly disagree, or not important at all; 9 indicated extremely appropriate, strongly agree, or extremely important). Options rated as first line were considered as very or usually appropriate, second line as somewhat appropriate, and third line as inappropriate. In completing the survey, respondents were asked to draw on their personal clinical experience in treating individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective and bipolar disorders as well as their knowledge of research and/or published literature. The survey was distributed to 42 experts in the US who were either researchers in mood and psychotic disorders with expertise in LAI trials or clinicians with extensive expertise in the use of multiple LAI formulations. The time required to complete the survey was approximately 2.5–3.0 hours. Each academic expert met two or more of the following inclusion criteria: has published in the area of adherence or LAI use as it relates to individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective and bipolar disorders; is a principal investigator or coprincipal investigator for studies involving LAIs for the treatment of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; has an advanced degree in psychology, medicine, or an associated field; and is responsible for the selection of treatment options for patients with schizophrenia/schizoaffective and bipolar disorders. Each clinician with extensive expertise fulfilled the following criteria (based on prescribing data): routinely prescribes LAIs in their practice; prescribes at least two different LAIs in their practice; has an advanced degree in psychology, medicine, or associated field; and is responsible for the selection of treatment options for their patients with schizophrenia/schizoaffective and bipolar disorders. Respondents received an honorarium for their participation in the survey and were blinded to the study sponsor. Respondents were informed of the purpose of the survey and invited to continue by clicking a web button, which was deemed as confirming agreement. This study only involved the use of survey procedures and did not involve children, and the responses were aggregated and anonymized such that none of the responses could be linked to any specific respondent; this study is exempt from approval by an institutional review board.

Statistical analyses

The presence or absence of consensus on each question was defined as a distribution unlikely to occur by chance using the chi-square test (P<0.05) across three ranges of appropriateness on the rating scale (ie, 1–3, 4–6, and 7–9). Consistent with previous expert consensus survey methodology,20 the mean rating with 95% CI was calculated for each option in a given question. Results were summarized graphically with a horizontal box representing the 95% CI for each consecutive option in a given question. Options receiving a rating of 9 by ≥50% of respondents were marked by an asterisk, and shading was used to indicate consensus. CIs of mean ratings were used to designate first-, second-, or third-line ratings (ie, items were first line if the bottom of the CI boundary was >6.5, second line if the bottom of the CI fell between 3.5 and 6.5, and third line [not appropriate] if the bottom of the CI was <3.5). Tests of significance were not performed for most items; however, wider gaps between CIs generally indicated smaller P-values.

Expert consensus related to initiation and maintenance treatment with LAIs in individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective and bipolar disorders is summarized in this study.

Results

Of 175 experts who were invited to take the survey, 42 (24%) agreed to participate, and 81% (34 out of 42) of those who received the survey completed it. A list of survey respondents and their demographics and experience have been provided in a companion paper.48 The majority of the expert panel was composed of psychiatrists (n=24), of whom seven were clinicians with extensive expertise in the use of multiple LAIs (high prescribers). Overall, experts had a relatively high level of clinical experience, with >50% reporting they spent either half, a majority, or all of their time in clinical practice. The expert panel also reported spending a mean of 30% of their time either treating or supervising the treatment of individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and 25% of their time either treating or supervising the treatment of individuals with bipolar disorder. Within the clinical practices of the selected experts, 33% of patients with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and 11% with bipolar disorder were being treated with LAIs. In response to the first survey question, which asked how confident these experts were in assessing their patients’ adherence to oral medication, most of the experts indicated that they were only somewhat confident (45%) or not very confident (33%).

Optimal practices and procedures before initiating an LAI and partnering with patients

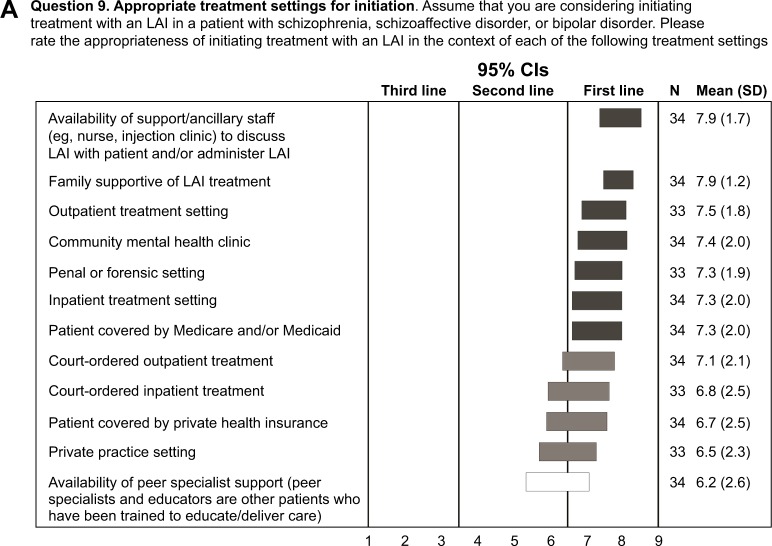

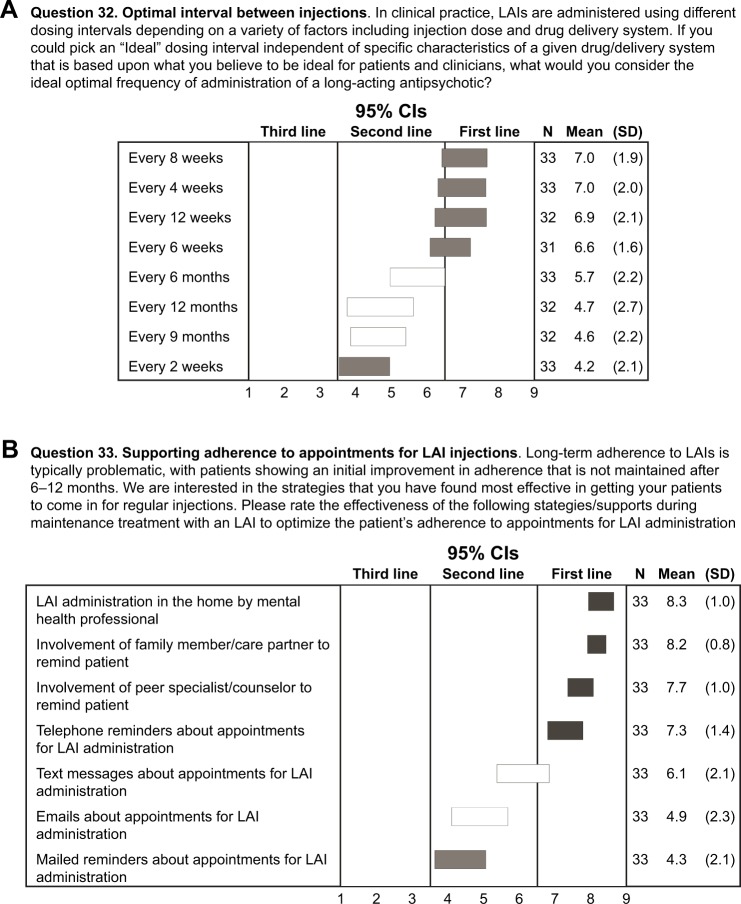

Appropriate treatment settings for initiation

Experts rated the appropriateness of initiating treatment with an LAI in the context of various predetermined treatment settings. The experts considered it appropriate to initiate an LAI in a wide range of treatment settings and clinical situations (Figure 1A). First-line consensus was achieved for outpatient, community mental health clinic, correctional or forensic, and inpatient treatment settings as well as the following situations: availability of support/ancillary staff to discuss LAIs with patient and/or administer LAI, family supportive of LAI treatment, and patient covered by Medicare and/or Medicaid. High second-line consensus was achieved for court-ordered inpatient or outpatient treatment, patients covered by private health insurance, and private practice settings.

Figure 1.

Procedures before initiating an LAI and partnering with patients.

Notes: (A) Appropriate treatment setting for initiating treatment with an LAI (rating scale: 1, not appropriate at all; 9, extremely appropriate), (B) important steps in initiating treatment with an LAI (rating scale: 1, not important at all; 9, extremely important), and (C) importance of discussing potential benefits of LAIs in motivating patients to use an LAI (rating scale: 1, not important at all; 9, extremely important). An asterisk in a bar represents an option that received the highest ranking of 9 by ≥50% of respondents. Horizontal bars represent CIs. Open bars indicate no consensus; shaded bars indicate consensus (dark shading: first line; medium shading: second line; light shading: third line). High second line: CI bar crosses the boundary with first line.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotic.

Important steps in initiating treatment

When rating the importance of various steps in initiating an LAI, >65% of experts gave a rating of 9 (first line; extremely important) to discussing the risks and benefits of LAI treatment with the patient and family/care partners as well as for obtaining the patient’s agreement to LAI treatment. Additional steps achieving consensus as being extremely important are shown in Figure 1B. Overall, the experts placed importance on educating patients and families, normalizing the use of LAIs, and engaging patients in a treatment plan that includes LAIs.

Partnering/discussing LAIs with patients

LAIs possess a number of potential advantages that may help patients accept treatment. Experts rated which LAI-associated benefits would motivate patients to use LAIs, and the following benefits were considered first line/extremely important (rating of 9 by ≥50% of experts; Figure 1C): a better chance of preserving functioning and achieving long-term goals if on continuous medication, reduced risk of relapse, and easier to be adherent (only need to remember to go for injections).

Factors to consider in selecting an LAI

Experts rated patient-, system-, and medication-related factors that might be considered in selecting a specific LAI (Table 1). The patient’s previous response to specific antipsychotics and history of side effects were rated as the most important patient-related factors to consider (first line; extremely important). Out-of-pocket patient expense and formulary/insurance restrictions were rated as the most important system-related factors (both rated as first line/usually important), whereas the most important medication-related factors were the clinician’s belief that a specific LAI would provide the best tolerability and efficacy profiles, availability of different formulations with varying dosing intervals, and the ability to administer the LAI via deltoid as well as gluteal injection (all first line/usually important [defined as a score of 7–8 on the rating scale]). Of note, no consensus was achieved on how important a history of violence/aggression, presence of comorbid substance abuse, or a history of suicidality would be in selecting a specific LAI.

Table 1.

Factors to consider in selecting an LAI

| Patient-related factors | System-related factors | Medication-related factors |

|---|---|---|

| First-line ratings,a mean (SD) | ||

| Patient’s previous response to LAI,b 8.2 (1.1) | Out-of-pocket expense for the patient, 8.1 (1.0) | Clinician believes the chosen LAI will have the best tolerability, 7.8 (1.5) |

| Weight gain, metabolic syndrome, symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, tardive dyskinesia, or parkinsonism with previous antipsychotic, 7.9 (1.2) | Formulary or insurance restrictions, 8.0 (1.1) | Clinician believes the selected LAI has the best chance of being efficacious for the specific patient, 7.7 (1.5) |

| Symptoms of hyperprolactinemia with previous antipsychotic therapy, 7.7 (1.3) | Availability of longer-acting formulation (injections can be given less frequently), 7.7 (1.5) | |

| Patient’s previous response to oral antipsychotic, 7.7 (1.3) | LAI that allows for longer interval when a dose is missed before oral augmentation required, 7.5 (1.0) | |

| Tardive dyskinesia with previous antipsychotic therapy, 7.4 (1.9) | Availability of different formulations with varying dosing intervals, 7.1 (1.5) | |

| Parkinsonism with previous antipsychotic therapy, 7.2 (1.4) | LAI that can be given via deltoid as well as gluteal injection, 7.0 (1.3) | |

| High second-line ratings,a mean (SD) | ||

| Akathisia, sedation, or sexual dysfunction with previous antipsychotic, 7.1 (1.8) | Clinician’s personal experience using a specific LAI, 6.9 (2.2) | Availability of prefilled syringes for LAI administration, 6.8 (1.5) |

| Persistent positive symptoms in a patient with SCZ, 6.9 (1.9) | No availability of appropriately monitored refrigeration facilities, 6.6 (2.1) | Availability of multiple dosing strengths in prefilled syringes, 6.7 (1.6) |

| Sedation with previous antipsychotic therapy, 6.7 (1.8) | Properties of the specific antipsychotic molecule, 5.9 (2.0) | |

| Sexual dysfunction with previous antipsychotic therapy, 6.5 (2.2) | Package insert recommends LAI dosing that takes into account hepatic metabolism status, 5.8 (1.7) | |

| Persistent manic symptoms in a patient with bipolar disorder, 6.5 (1.8) | ||

| Medical comorbidity involving cardiovascular disease, 6.3 (1.9) | ||

| Medical comorbidity involving hepatic disease/dysfunction, 6.2 (2.0) | ||

| Borderline or prolonged QTc interval, 6.2 (2.1) | ||

| Persistent depressive symptoms in a patient with SCZ, 6.0 (1.9) | ||

| Persistent depressive symptoms in a patient with bipolar disorder, 5.9 (2.1) | ||

| Persistent negative symptoms in a patient with SCZ, 5.8 (2.2) |

Notes:

CIs of mean ratings were used to designate first-line or high second-line ratings (ie, items were first line if the bottom of the CI boundary was >6.5 and high second line if the bottom of the CI boundary was ≥3.5 and the top of the CI boundary was >6.5).

Options that received the highest rating of 9 by ≥50% of experts.

Abbreviations: LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotic; SCZ, schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder.

Establishing tolerability and efficacy when initiating treatment

Assuming a decision has been made to use a specific LAI, experts rated the most appropriate strategies for establishing tolerability and efficacy of the LAI in a patient who had not previously received this LAI (ie, a unique molecule). There was little consensus regarding the best strategy in establishing the tolerability and efficacy of a molecule (specific drug) before initiating the LAI. Overall, the experts appeared to prefer shorter intervals (4–14 days) of oral medication before initiating treatment with an LAI of the same molecule (second-line rating). However, there was consensus that they would not recommend continuing the oral medication for >6 weeks before beginning an LAI with the same molecule (third-line rating; usually inappropriate [defined as a score of 2–3 on the rating scale]). The strategy to continue treatment with oral medication for >8 weeks to ensure both tolerability and efficacy before initiating an LAI with that same molecule received the lowest rating and expert consensus as being usually inappropriate.

Dosing of initial injections

Respondents rated the appropriateness of prescribing a lower initial dose or a higher dose of the LAI than recommended in the package insert in individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder. Generally, there was little support for initiating an LAI at doses lower or higher than recommended in the package insert with the following exceptions: experts gave high second-line ratings to starting with a lower initial dose of the LAI in older patients as well as patients who have extrapyramidal side effects to minimize side effect burden. The experts gave high second-line ratings to initiating treatment with a higher initial dose of the LAI for patients who had a history of requiring larger than usual daily dosages of oral antipsychotics to achieve treatment response or to prevent relapse. The option to give either a lower or higher initial dose than recommended in the package insert to all individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder received the lowest rating and achieved consensus as being usually inappropriate.

Timing of the second injection

Experts rated the most important factors that would determine the timing of the second LAI injection. Experts achieved consensus that the most important factors were the package insert recommendations and the patient showing an increase in symptoms before the end of the dosing interval (first-line recommendation; both were rated as usually important). High second-line consensus was also attained for the length of time to achieve therapeutic levels (usually appropriate), pharmacologic/molecular properties of the antipsychotic agent (usually appropriate), presence of side effects believed to be due to the LAI (sometimes appropriate [defined as a score of 4–6 on the rating scale]), and severity of the patient’s psychiatric symptoms (sometimes appropriate).

Managing oral antipsychotics during and after initiation of an LAI

When queried regarding starting dose, the use of loading doses, the procedure for switching from oral antipsychotic to LAI (eg, duration of overlap), and interval between injections, the experts overwhelmingly agreed that they generally follow package insert recommendations if provided. When asked to rate appropriateness of several schedules for tapering and discontinuing oral supplementation (if recommended in the package insert [PI]) after the period of time recommended in the PI, the experts gave high second-line ratings to discontinuing oral supplementation exactly as recommended in the package insert. They would also consider tapering off the oral antipsychotic over an additional 1–3 weeks (second-line rating); however, they would not recommend continuing oral antipsychotic supplementation beyond 3 weeks (ie, maintain regular dosing for only a short time frame and not longer term). The strategy to taper or discontinue oral antipsychotic medication after an additional period of >3 months after the period of oral supplementation recommended in the package insert received the lowest rating and consensus as being usually inappropriate.

Managing side effects

Experts rated the appropriateness of various medications to manage distressing side effects in patients who had recently initiated LAI treatment and in whom the expert had already considered or tried a decrease in LAI dose. Experts recommended the following medications as first-line (usually appropriate) treatments for the following side effects: β-blocker for akathisia/restlessness; an anticholinergic for dystonia or parkinsonism; a non-benzodiazepine sedative/hypnotic for insomnia; and metformin, statins, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for the metabolic syndrome component abnormalities of elevated glucose, lipid abnormalities, and high blood pressure, respectively.

In addition, high second-line recommendations (all were rated as sometimes appropriate) achieved consensus for the use of a sedative/hypnotic or anticonvulsive agent for agitation, oral partial D2 agonist antipsychotic (if not on partial D2 agonist LAI) for prolactin-related side effects, and a drug targeting erectile dysfunction for sexual dysfunction.

Optimal practices for continuation and maintenance treatment with LAIs

Optimizing maintenance treatment

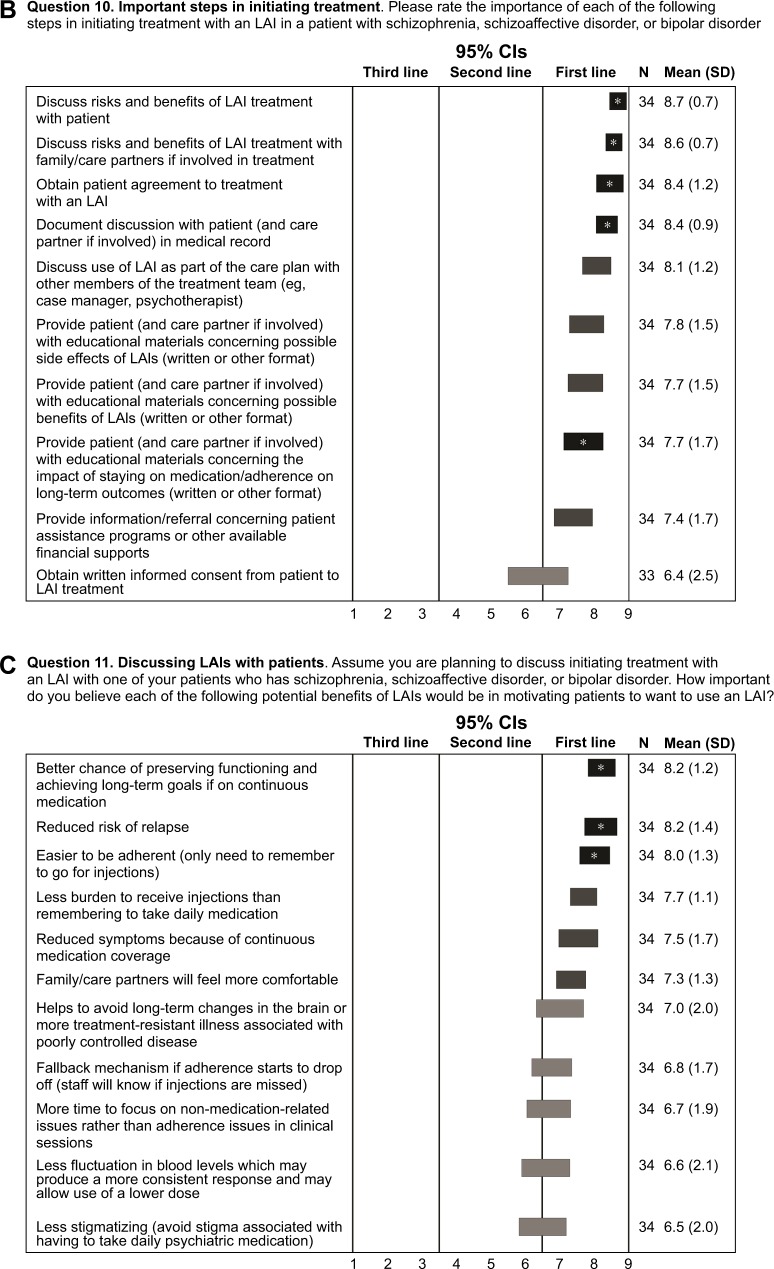

For maintenance treatment, experts rated the ideal time interval between LAI injections, independent of the specific characteristics of the drug/delivery system. Although no first-line recommendations were achieved, high second-line ratings (usually appropriate) were given for intervals ranging from 4 to 12 weeks, with no consensus on longer intervals ranging from 6 to 12 months and little support for injections given at shorter intervals (ie, every 2 weeks; Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Optimizing maintenance treatment and supporting LAI adherence.

Notes: (A) Optimal interval between injections (rating scale: 1, extremely inappropriate; 9, extremely appropriate) and (B) effectiveness of strategies during maintenance treatment with an LAI to optimize the patient’s adherence to appointments for LAI administration (rating scale: 1, likely to be ineffective; 9, likely to be effective). Horizontal bars represent CIs. Open bars indicate no consensus; shaded bars indicate consensus (dark shading: first line; medium shading: second line; light shading: third line). High second line: CI bar crosses the boundary with first line.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotic.

Supporting adherence to appointments for LAI injections

Because maintaining long-term adherence is a difficult goal for many patients,21 experts rated strategies to optimize adherence to appointments for LAI administration. Four strategies achieved consensus and were recommended by the experts as first-line (usually appropriate) methods to optimize adherence to appointments for LAI administration: LAI administration in the home by mental health care professional, involvement of family member/partners in care, involvement of peer specialist/counselor in care, and telephone reminders about appointments for LAI administration (Figure 2B). Consensus was not achieved among the experts on the utility of technology-focused alerts (eg, text messages and emails) in reminding patients to keep an appointment; there was only minimal support for using mailed reminders.

Assessing response: most important clinical symptoms

Experts rated the clinical symptoms they considered important to target in evaluating therapeutic response to an LAI. In individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, experts gave first-line recommendations to monitoring positive symptoms (eg, psychosis, delusions, and hallucinations), which received the highest rating of 9 from 79% of the experts (extremely important), and functional status (eg, social and occupational; considered to be usually important). In individuals with bipolar disorder, experts considered psychotic symptoms, manic/hypomanic symptoms, and mixed symptoms, all of which received the highest rating of 9 from 79% of the experts (extremely important), as most important in evaluating therapeutic response to an LAI. Functional status and rate of mood cycling were rated as usually important.

Defining an adequate trial of an LAI

Because the definition of an adequate LAI trial is not established, experts rated how important they considered the time duration of treatment versus the number of injection cycles that had been completed to determine whether a patient has had an adequate trial of an LAI. There were no first-line ratings. The experts gave high second-line ratings to both number of cycles once steady-state plasma levels are reached (rated as 9 by 30% and 7–9 by 67%) and duration of time in determining whether a patient has had an adequate trial of an LAI (rated as 9 by 19% and 7–9 by 61%).

Experts were then asked to assume that they had an individual with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had been maintained on an LAI at the maximum dosage they were comfortable administering for this patient and that the patient had failed to achieve an adequate response. Experts rated the appropriateness of a number of definitions of an adequate therapeutic trial of an LAI in this predefined setting. None of the options received first-line ratings. The experts gave high second-line ratings to the need for multiple cycles of LAI injections to ensure an adequate therapeutic trial, with the least conservative definition being the number of cycles needed to achieve steady state and a more conservative definition involving one to two cycles beyond steady state or at least 12 weeks of treatment. The parameter of giving one to two injection cycles less than needed to reach full steady state received the lowest rating and consensus as being usually inappropriate.

Similar responses were obtained for determining an adequate LAI therapeutic trial for an individual with bipolar disorder. In addition, 66% of the experts indicated that the patient’s history of mood cycling intervals would affect their decision concerning the numbers of cycles/periods of time they would continue LAI treatment before deciding whether the patient was having an adequate response.

Strategies for inadequate response

If an individual with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder was at steady state of the maximum allowed or tolerated dose of an LAI and had some improvement but either continued to experience persistent residual symptoms or began to develop breakthrough symptoms, the experts rated the appropriateness of treatment strategies depending on the type of symptoms involved (ie, positive/psychotic, negative, or cognitive symptoms; Table 2). If positive symptoms occurred (eg, hallucinations, delusions, and aggression), first-line consensus emerged for switching to a medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia (rated as usually appropriate). High second-line consensus was achieved for switching the patient to an alternative LAI with a different molecular base or adding the same oral antipsychotic as the LAI (both rated as sometimes appropriate). Adding estrogen or other hormonal treatments achieved consensus as being usually inappropriate. If negative symptoms occurred (eg, lack of motivation), no first-line consensus emerged for any of the strategies. High second-line consensus emerged for switching to a medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia (rated as usually appropriate). Adding an oral medication to slow down second-pass metabolism of the LAI received the lowest rating and consensus as being usually inappropriate. Finally, if cognitive symptoms occurred, no first-line or high second-line recommendations emerged, and no consensus on any second-line strategy was achieved by the experts. Adding electroconvulsive therapy to the treatment regimen received the lowest rating and consensus as being usually inappropriate.

Table 2.

Strategies for an inadequate response to an LAI in patients with schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder

| Type of persistent or breakthrough symptom | First linea | High second linea |

|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder | ||

| Positive symptoms (eg, hallucinations, delusions, aggression) | • Switch to a medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, 7.4 (1.9) | • Switch to an alternative LAI with a different molecular base, 6.5 (1.9) • Add the same oral antipsychotic as the LAI, 6.3 (2.0) • Decrease time period between injections to a shorter interval,b 6.1 (2.4) |

| Negative symptoms | • Switch to a medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, 6.5 (2.4) | |

| Cognitive symptomsc | ||

| Bipolar disorder | ||

| Manic symptoms | • Switch to a different mood stabilizer if the patient is currently being treated with one, 7.4 (1.6) • Add lithium, 7.4 (1.3) • Add an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer the patient has not previously received, 7.4 (1.3) |

• Add an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer to which the patient has previously had at least a partial response, 7.1 (1.8) |

| Depressive symptoms | • Add lithium, 6.3 (1.9) • Add an antidepressant medication if the patient is already receiving lithium or an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer, 6.1 (2.3) • Add an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer, 6.0 (2.0) |

|

| Psychotic symptoms | • Switch to a medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, 5.9 (2.6) • Switch to an alternative LAI with a different molecular base, 5.8 (2.1) • Add the same oral antipsychotic as the LAI,b 5.7 (2.4) |

|

Notes:

CIs of mean ratings were used to designate first-line or high second-line ratings (ie, items were first line if the bottom of the CI boundary was >6.5 and high second-line if the bottom of the CI boundary was ≥3.5 and the top of the CI boundary was >6.5).

No consensus was reached.

No first-line or high second-line recommendations; no consensus on any second-line strategy.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotic.

Similarly, if an individual with bipolar disorder was at steady state for the maximum allowed or tolerated dose of an LAI and had some improvement but either continued to experience persistent residual symptoms or began to develop breakthrough symptoms, the experts rated the appropriateness of treatment strategies depending on the type of symptoms involved (ie, manic, depressive, or psychotic symptoms; Table 2). If manic symptoms occurred, first-line consensus emerged for switching to a different mood stabilizer if the patient is currently being treated with one, adding lithium, or adding an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer the patient has not previously received (all rated as usually appropriate). There was no consensus for any recommended second-line strategy. The two strategies receiving the lowest rating and achieving consensus as being usually inappropriate were adding oral medication to slow down second-pass metabolism of the LAI or adding a different LAI with alternating injection time points. No first-line recommendations were given in case of occurrence of depressive symptoms; however, high second-line consensus emerged for the following strategies: adding an antidepressant medication if the patient is already receiving (or HCP is adding) lithium or an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer, or adding an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer (all rated as sometimes appropriate). Adding an oral medication to slow down second-pass metabolism of the LAI received the lowest rating and consensus as being usually inappropriate. The experts did not arrive at first-line recommendations for any of the treatment strategy options for persistent or breakthrough psychotic symptoms occurring on LAI treatment; however, high second-line consensus emerged for switching to a medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia or switching to an alternative LAI with a different molecular base. The lowest rated strategy was the same as that shown for depressive symptoms.

Identifying and defining lack of treatment response

Although lack of treatment response is typically defined as a failure to respond to multiple adequate trials of oral antipsychotic medications in individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder, defining nonresponse to treatment in the context of treatment with an LAI is not clear. A confounding factor for oral antipsychotic drugs is that many individuals are nonadherent or only partially adherent. Therefore, experts were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the statement that schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder should not be identified as treatment-resistant “without” at least one trial of an LAI (to ensure that what appears to be refractory illness is not actually the result of poor adherence with prescribed treatment). For schizophrenia, 21% of experts strongly agreed (score of 9 on the rating scale) with the statement, 67% agreed (rating of 7–9), 21% somewhat agreed (rating of 4–6), and 12% disagreed. Thus, the majority of experts (nearly 90%) believe that an LAI trial is needed to determine the lack of therapeutic response to antipsychotic treatment in individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder.

For bipolar disorder, expert agreement was not as high as for individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder; however, a majority of experts agreed that an LAI trial was needed to determine the lack of therapeutic treatment response in bipolar disorder (9% strongly agreed [rating of 9], 52% agreed [rating of 7–9], 33% somewhat agreed [rating of 4–6], and 15% disagreed).

Medical monitoring of patients being treated with an LAI (no major comorbidities)

Most important medical parameters to monitor

Safety monitoring is important in patients being treated for severe mental illness;22,23 however, most of the available guidance for safety monitoring is related to treatment with antipsychotics in general and not specifically for LAIs. In an individual being treated with an LAI who has schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder and does not have any major comorbidities (eg, diabetes, hypertension, or active cardiovascular disease), experts rated body weight/body mass index (BMI), fasting lipid levels, and standardized assessments for tardive dyskinesia as the most important medical parameters to monitor (highest rating of 9 by ≥50% of the experts). Additional first-line parameters were hemoglobin HbA1c and fasting glucose level (rated as usually appropriate).

Frequency of medical monitoring

Experts rated the frequency of medical monitoring for the average patient treated with an LAI, assuming the patient had no major medical conditions during and after the first 6 months of treatment (Table S1). The medical parameters receiving the highest ratings by the experts were similar irrespective of the time period assessed (ie, body weight/BMI and blood pressure), although the experts’ responses indicated that, for some parameters (eg, liver function and prolactin abnormalities), the effects would not be expected to appear immediately after LAI initiation but would rather take weeks to months to change with sustained LAI treatment.

Switching between LAIs

Because there is currently little guidance available on how to switch from one LAI to another, the experts rated different methods of switching LAIs for a patient who had failed to respond to an LAI after what the experts considered to be a full therapeutic trial. There was little agreement on appropriate ways to switch between LAIs, with no LAI switching options rated as extremely appropriate. Regardless of whether therapeutic levels are reached quickly (eg, within days) or over a significant period of time (eg, within weeks) with the prior LAI, if levels are reached quickly with the new LAI, the experts agreed that the new LAI can be given at the same time the previous LAI would have been given and at the same dose recommended in the PI for the new LAI, without providing a concomitant oral antipsychotic. Of note, free text comments from the experts stressed the importance of first establishing oral tolerability of the new antipsychotic. In contrast, if therapeutic levels are reached quickly with the prior LAI but over a longer period with the new LAI, experts agreed that it is sometimes appropriate to supplement therapy with an oral antipsychotic during the switch.

No first-line or high second-line agreement was achieved, and no consensus was reached on the best strategy for switching when significant time is needed to reach therapeutic levels with both the previous and new LAI. Consensus was reached for the following strategies being usually inappropriate: 1) substituting at the same time the previous LAI would have been given with either a higher dose of the new LAI (whether or not an oral antipsychotic is also given) or a lower dose of the new LAI, and 2) substituting at an earlier time than the previous LAI would have been given, whether at a lower or higher dose of the new LAI.

Among the experts who responded (n=31), the most frequent reasons for switching LAIs were suboptimal efficacy and side effects (38% and 28%, respectively). Finally, of the 30 who responded regarding combining LAIs, 21 (70%) did not support this practice.

Limitations

Generalizability of the findings could be reduced by the fact that a relatively small number of experts invited to take the survey actually agreed to take the survey.

Because many clinically relevant areas lacked clinical trial data, recommendations were based on both trial data and clinical experience and opinion.

Discussion

Although recent studies indicate that the use of LAIs may have the potential to prevent relapse compared with oral antipsychotic use,24–26 and although second-generation LAI formulations are widely available in the US, it has been estimated that only 13%–28% of eligible US patients are actually prescribed LAIs.9 One explanation for why these agents are potentially underprescribed may be the current lack of published guidance on how to initiate and maintain treatment with these agents. The purpose of this expert consensus survey was to provide recommendations to help fill in some of the existing knowledge gaps concerning the appropriate use of LAIs in the treatment of individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder. Results pertaining to initiating and maintaining LAI treatment are reported in this study (summary is given in Table 3), whereas additional results pertaining to appropriate patients and clinical scenarios are reported in a companion paper.48 Overall, expert recommendations in the current survey align closely with those in the AFPBN guidelines for the use of LAIs in serious mental illness18 while addressing additional clinical topics and practical aspects of LAI treatment.

Table 3.

Summary of first-line recommendations for initiating and maintaining treatment with an LAI

| Practices/procedures | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Agreeing to LAI trial | • Discuss risks/benefits with patient and family/care partners • Obtain patient agreement • Document discussion with patient • Provide educational materials |

| Choosing an agent | Consider: • Patient’s previous response to specific antipsychotics, including history of side effects with different agents • Metabolic and EPS side effects experienced with previous antipsychotics • Out-of-pocket expense and formulary restrictions • Clinician’s expectation of good tolerability and efficacy for specific LAI • Availability of formulations with varying dosing intervals • Option for deltoid or gluteal injection |

| LAI initiation | • Sufficient tolerability to the LAI should be established for the oral medication before initiating LAI with that same molecule • When starting LAI, use concomitant oral antipsychotic according to package insert • Start with intended maintenance dose for most patients • Give second injection according to schedule in package insert, unless symptoms increase before the end of dosing interval |

| LAI trial | • Duration of trial should allow achievement of steady state or one to two cycles after steady state is reached • Measure treatment response based on the presence of positive symptoms and/or functional status (SCZ) or based on psychotic symptoms, manic/hypomanic symptoms, functional status, and/or mixed symptoms (BP) • If steady state of maximum tolerated dose is reached but symptoms persist: ◦ (SCZ) positive symptoms – switch to medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia; negative or cognitive symptoms – no first-line consensus ◦ (BP) manic symptoms – add lithium or mood stabilizer or switch to a different mood stabilizer; depressive or psychotic symptoms – no first-line consensus |

| Maintenance treatment | • Support continued injections through ◦ Appointment reminders (by clinic [phone], family member, care partner, peer specialist, counselor) ◦ LAI administration in the home by a mental health professional • Address side effects • Monitor body weight, BMI, blood pressure, liver function, metabolic parameters, prolactin, EPS |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, bipolar disorder; EPS, extrapyramidal symptoms; LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotic; SCZ, schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder.

Before prescribing an LAI, the majority of experts in this survey felt it was extremely important to discuss the risks/benefits with the patient and family/care partners, obtain a patient’s agreement to LAI treatment, and document discussion with a patient/care partner in the medical record when initiating an LAI. Similarly, when partnering with patients, they felt it was extremely important to explain the most meaningful advantages of using an LAI,27 including a better chance of preserving function and achieving long-term goals if on continuous medication, a reduced risk of relapse, and greater ease of adhering to treatment.

Experts in this survey determined that the most important patient-related factor in selecting a specific LAI was a patient’s previous response to the respective oral antipsychotic or LAI (if provided in the past). Although there is limited guidance available in the published literature to help choose a specific LAI for a particular patient, a review by Sacchetti et al28 suggests that LAIs appear to have similar tolerability to oral antipsychotics, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines propose using the same risk assessment criteria for selecting either an LAI or an oral antipsychotic.29

Overall, expert consensus in this survey was achieved for the appropriate treatment settings in which to initiate an LAI. However, although experts agreed that efficacy and tolerability of an oral antipsychotic should be established before the initiation of a new LAI, there was little consensus on the required duration of the oral treatment phase. AFPBN guidelines recommend offering LAIs as first-line treatment to patients, but if the patient is going to be switched from an oral antipsychotic to an LAI, they recommend prescribing the oral antipsychotic to establish an effective dose before initiating the LAI.18 The NICE schizophrenia guidelines recommend starting with a small test dose of the LAI,29 whereas the British Association of Psychopharmacology guidelines for bipolar disorder recommend using an oral antipsychotic to establish the best tolerated dose before initiating an LAI.30 Establishing ideal LAI treatment initiation strategies remains an important knowledge gap that likely reflects a lack of both prospective studies and data from observational databases that might shed light on prescribing practices associated with optimal outcomes.

Upon initiation of treatment with a specific LAI in an individual with schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder, an appropriate injection schedule must be established. The majority of the experts agreed that they would follow the PI recommendations for the starting dose, use of a loading dose, procedure for switching from an oral antipsychotic to the LAI, and the interval between injections during the initiation of an LAI. The expert responses also showed that they generally favor a relatively short interval (4–14 days) of oral medication before initiating an LAI of the same molecule and that they would not recommend continuing the oral medication for >6 weeks before starting the LAI. However, survey responses showed no first-line ratings for the ideal time interval between injections; high second-line ratings were given for an interval ranging between 4 and 12 weeks, with little support for shorter injection intervals. These recommendations complement the fact that most available LAIs have an injection interval of ≥4 weeks.8 LAIs with longer dosing intervals are an important consideration for patients who are either unwilling or unable to make more frequent in-person visits. Additional research needs to be conducted to determine the effectiveness of the available LAIs with particular dosing schedules and must include individual patient preferences/characteristics. Such research should provide data to enable a consensus on recommended dosing strategies.

Because the efficacy of an antipsychotic may vary depending on the individual patient, determination of treatment response is a high priority in the management of LAIs. The majority of experts rated the presence of positive symptoms such as psychosis, delusions, and hallucinations as being an extremely important (ie, received the highest possible rating from a majority of the experts) factor in assessing LAI response in an individual with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder. For bipolar disorder, the highest possible rating (extremely important) was given by 79% of the experts for assessing the occurrence of psychotic symptoms, manic/hypomanic symptoms, functional status, and mixed symptoms. Depressive symptoms received the lowest ratings for LAI response evaluation in individuals with bipolar disorder. This may reflect the fact that more antipsychotic drugs have US Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of bipolar mania compared with bipolar depression.31,32 Moreover, this seeming disconnect with the functional impact of depression on outcomes may also stem from the fact that LAIs have no indication for depression as monotherapy and that other oral agents or psychosocial treatments will need to be prescribed to address depression and/or negative symptoms. The two LAIs currently approved for the treatment of bipolar I disorder, risperidone LAI and aripiprazole once monthly, have shown efficacy in reducing or preventing manic episodes, not depressive episodes.33–35

Long-term adherence to antipsychotics has historically been an important issue for many individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder. It is important to identify whether apparent lack of response is due to either nonadherence or the illness itself. The majority of experts in this survey believed that nonadherence and lack of efficacy of non-clozapine oral antipsychotic drugs could not be properly identified without ≥1 trial of an LAI in schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder; however, no first-line consensus was achieved. Moreover, when respondents were asked to define an adequate LAI trial in patients with schizophrenia, no first-line consensus emerged. The experts did give a high second-line rating for multiple cycles of LAI injections being necessary to define an adequate LAI trial. Similarly, no first-line consensus emerged in individuals with bipolar disorder; however, the experts again gave high second-line ratings to the number of injection cycles needed to reach steady state or one to two injection cycles more than needed to reach full steady state. An important consideration in defining an adequate LAI trial is how the recommended trial duration can be achieved in clinical practice. However, an LAI trial is generally initiated after there has been an indication of efficacy and tolerability of oral antipsychotic. Therefore, the degree of stability or further improvement/worsening after the switch to an LAI needs to be monitored in an ongoing manner. Given the effort and monitoring burden of clozapine therapy, using an LAI trial to clearly differentiate pseudoresistance to an antipsychotic drug because of poor adherence versus genuine lack of therapeutic response has the potential to improve identification of individuals who warrant a different treatment or clozapine trial. A broader use of LAIs could help address the gross underutilization of clozapine in many treatment settings.36,37

Another important consideration for the clinician who has initiated LAI treatment is persistent residual symptoms or the development of breakthrough symptoms in a patient who is already at steady state for the maximum allowed or tolerated dose. Experts achieved a first-line consensus for the strategy of switching to a medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia in patients with continued positive symptoms and failure on an LAI if this constituted at least a second antipsychotic trial. However, no first-line recommendations emerged for the treatment of negative or cognitive symptoms, likely owing to the fact that there are no approved and effective treatments available for these two symptom constellations that would provide the basis for a rational switch.38 With regard to bipolar disorder, if a patient had ongoing manic symptoms despite an LAI trial, first-line consensus emerged for switching to a different mood stabilizer if the patient was currently being treated with one, adding lithium, or adding an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer if the patient had not previously received one. These recommendations are consistent with bipolar disorder guidelines.30,39 Unlike schizophrenia, where there is no high-quality evidence for the efficacy of polypharmacy with a second antipsychotic40 and other psychotropic agents,38 combination treatment with two mood stabilizers or an antipsychotic with a mood stabilizer has demonstrated efficacy and regulatory approval for bipolar disorder.30 No first-line consensus was achieved for individuals with bipolar disorder who had depressive or psychotic symptoms. However, additional reasons for a lack of first-line consensus for treating residual negative/cognitive symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia or depressive/psychotic symptoms in individuals with bipolar disorder may relate to the limited role of antipsychotic drugs with regard to these symptoms; a hypothesis that is consistent with published findings.41,42

Notably, consistent with a recent expert guideline on the definition of treatment-resistant schizophrenia,43 experts in this survey also considered it prudent to have patients who seem to not be responding to first-line treatments for schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder to undergo ≥1 trial with an LAI to rule out “pseudoresistance” due to insufficient treatment adherence.

The issue of how to switch a patient from one LAI to a different LAI is another important consideration for clinicians. The lack of consensus in this survey, as well as the absence of any associated first-line ratings for switching strategies, reflects the lack of clinical research data available to guide LAI switching. The AFPBN guidelines do provide limited guidance concerning switching between LAIs. The AFPBN first-line strategy is to initiate a new LAI only after discontinuing the current LAI while coordinating the switch such that the time since the last injection will correspond to the interval between both injections.18 In addition, it is recommended that the initial dose of the new LAI should correspond to an equivalent dose of the previous LAI if possible. Notably, the expert recommendations from this survey acknowledge the importance of considering pharmacokinetic properties when switching between agents. More specifically, it is recommended that the appropriate time interval for initiating a new LAI should be based on how quickly the therapeutic levels of both LAIs are attained, and the oral tolerability with the new antipsychotic should be established before switching agents. In addition, oral supplementation should be given when switching to an LAI that takes a substantial amount of time to reach therapeutic levels but not when switching to an LAI that reaches therapeutic levels quickly.

With regard to adverse effect and physical health monitoring in individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder treated with an LAI, expert recommendations were generally consistent with those of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders23 and the European Psychiatric Association.22 Although there is limited guidance from the published literature to help choose a specific LAI for a particular patient, a review28 and a meta-analysis44 suggested that the tolerability of LAIs appears to be similar to that of oral antipsychotics, and the NICE guidelines propose using the same risk criteria to select either an LAI or an oral antipsychotic.29 The AFBPN guidelines recommend offering LAIs as first-line treatment, but in the event of a switch from an oral antipsychotic to an LAI, they recommend giving the oral antipsychotic for an appropriate length of time to establish an effective dose before initiating the LAI.18 The NICE schizophrenia guidelines recommend starting with a small test dose of the LAI,29 whereas the British Association of Psychopharmacology guidelines for bipolar disorder recommend using an oral antipsychotic to establish the best tolerated dose before initiating an LAI.30

Limitations to the interpretation of this expert consensus survey include low overall response rate and relatively small sample size. Because the survey took about 2.5–3 hours to complete, there is also a risk of inconsistent responses. Furthermore, although such an analysis would be of interest, an insufficient number of responses were received to allow comparisons between responses from researchers and high-volume clinical prescribers. It should also be noted that the survey questions mostly considered LAIs as a group and did not differentiate individual LAI-specific factors; however, some of the differences were implicit when the survey respondents were asked to consider the package inserts. Because the survey was limited to US experts, the responses most likely reflected opinion on atypical antipsychotics more so than typical antipsychotics although the type of antipsychotic was not specified in the survey. Expert recommendations were based on consideration of clinical trial data, clinical experience, and opinion. Although the latter could weaken the impact and generalizability of the recommendations, expert consensus can provide guidance in areas where clinicians need to make decisions and where clinical trial data are missing. Finally, the recommendations reflect experiences of experts in the US; the treatment landscape may differ in other countries. Strengths of this study include a high overall survey completion rate, the blinded format (survey respondents were not provided information on funding source), and the national representation of experts. Importantly, the survey methodology has previously been used to provide guidance for treatment decisions in individuals with schizophrenia45,46 and bipolar disorder.47

Conclusion

Although LAIs are widely available and have clinical benefits for individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder, these agents are currently underutilized. Because clinical data are lacking, the findings from this expert consensus survey may help provide clinical guidance/recommendations to clinicians on initiating and maintaining LAIs in individuals with schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder. These expert recommendations may also provide a foundation for additional clinical research to better understand the role of LAIs in these clinical groups.

Significant outcomes

The most important factor in long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI) selection was patient response and/or the side effect profile with previous antipsychotics.

Experts agreed that oral antipsychotic efficacy and tolerability should be established before switching to an LAI, but opinions varied with regard to the minimum time period.

Because levels of adherence are frequently unclear, most experts agreed that ≥1 adequate LAI trial is needed before the lack of antipsychotic efficacy can be determined.

Supplementary material

Table S1.

Frequency of medical monitoring during and after the first 6 months of treatment with LAIs

| During the first 6 months of LAI treatment

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experts’ endorsing option, n | Do not monitor | Baseline | After 1 month | After 2 months | After 3 months | After 6 months |

| Body weight/BMI | 0 | 30 | 28 | 24 | 24 | 29 |

| Blood pressure | 2 | 29 | 20 | 13 | 20 | 23 |

| Electrocardiogram | 16 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Fasting glucose level | 0 | 28 | 9 | 4 | 16 | 23 |

| Fasting lipid levels | 0 | 28 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 23 |

| HbA1c | 2 | 27 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 23 |

| Liver function testing | 5 | 24 | 5 | 1 | 12 | 15 |

| Prolactin level if the patient is being treated with a medication with the potential to raise prolactin | 10 | 15 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 16 |

| Standardized assessments for extrapyramidal symptoms (parkinsonism, akathisia) | 5 | 22 | 17 | 11 | 22 | 22 |

| Standardized assessments for tardive dyskinesia | 5 | 25 | 7 | 6 | 17 | 25 |

| Waist circumference | 15 | 16 | 7 | 8 | 14 | 16 |

|

| ||||||

|

After the first 6 months of LAI treatment

| ||||||

| Experts’ endorsing option, n | Do not monitor | At 8 months | At 10 months | At 1 year | Every 6 months thereafter | Every year thereafter |

|

| ||||||

| Body weight/BMI | 0 | 16 | 15 | 21 | 25 | 11 |

| Blood pressure | 1 | 11 | 10 | 22 | 17 | 16 |

| Electrocardiogram | 14 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 14 |

| Fasting glucose level | 1 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 12 | 18 |

| Fasting lipid levels | 0 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 10 | 20 |

| HbA1c | 2 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 10 | 18 |

| Liver function testing | 4 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 7 | 19 |

| Prolactin level if the patient is being treated with a medication with the potential to raise prolactin | 12 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 6 | 14 |

| Standardized assessments for extrapyramidal symptoms (parkinsonism, akathisia) | 5 | 9 | 8 | 18 | 21 | 6 |

| Standardized assessments for tardive dyskinesia | 5 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 21 | 8 |

| Waist circumference | 14 | 3 | 3 | 13 | 11 | 7 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotic.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. Editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Sheri Arndt, PharmD, and Alan Klopp, PhD, of C4 MedSolutions, LLC (Yardley, PA, USA), a CHC Group company, with funding from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., and H. Lundbeck A/S.

Footnotes

Disclosure

MS, MB, CUC, and JMK received consulting fees from Otsuka for their roles in the beta testing of the survey and data analysis for this study. MS has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Reinberger Foundation, Reuter Foundation, Alkermes, Otsuka, and the Woodruff Foundation; has been a consultant for Bracket, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Pfizer, Prophase, Health Analytics and Supernus; has received royalties from Johns Hopkins University Press, Lexicomp, Oxford University Press, Springer Press, and UpToDate; has participated in continuing medical education activities for the American Physician Institute, CMEology, and MCM Education; and was compensated by Otsuka for her work on the survey development and data analysis for this study. RR is a paid consultant for Otsuka and was compensated for her work on the survey and data analysis by Otsuka. SNL was an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. at the time of the study. MB has received grant or research support from the NIH and Otsuka. JMK has received honoraria for lectures and/or consulting from Alkermes, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Forrest, Genentech, Intracellular Therapeutics, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Neurocrine, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Proteus, Reviva, Roche, Sunovion, Takeda, and Teva and is a shareholder of MedAvante, LB Pharma, and the Vanguard Research Group. FD is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization. HF is an employee of Lundbeck. CUC has received grant or research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Bendheim Foundation, and Takeda; has served as a member of advisory boards/the Data Safety Monitoring Boards for Alkermes, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Sunovion; has served as a consultant to Alkermes, Allergan, the Gerson Lehrman Group, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, Medscape, Otsuka, Pfizer, ProPhase, Sunovion, Supernus, and Takeda; has presented expert testimony for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Otsuka; and has received honorarium from Medscape and travel expenses from Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sunovion, and Takeda. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Fagiolini A, Alfonsi E, Amodeo G, et al. Switching long acting antipsychotic medications to aripiprazole long acting once-a-month: expert consensus by a panel of Italian and Spanish psychiatrists. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(4):449–455. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2016.1155553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(1):1–44. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morken G, Widen JH, Grawe RW. Non-adherence to antipsychotic medication, relapse and rehospitalisation in recent-onset schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1–46. 47–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson TJ, Owen RR, Thrush CR, et al. A pilot study of barriers to medication adherence in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):211–216. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane JM, Eerdekens M, Lindenmayer JP, Keith SJ, Lesem M, Karcher K. Long-acting injectable risperidone: efficacy and safety of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1125–1132. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Non-adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(3):216–226. doi: 10.1002/wps.20060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl 3):1–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15032su1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brissos S, Veguilla MR, Taylor D, Balanza-Martinez V. The role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a critical appraisal. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(5):198–219. doi: 10.1177/2045125314540297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gigante AD, Lafer B, Yatham LN. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(5):403–420. doi: 10.2165/11631310-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nasrallah HA. The case for long-acting antipsychotic agents in the post-CATIE era. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115(4):260–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957–965. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kishimoto T, Robenzadeh A, Leucht C, et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):192–213. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Assessing the comparative effectiveness of long-acting injectable vs. oral antipsychotic medications in the prevention of relapse provides a case study in comparative effectiveness research in psychiatry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8 suppl):S37–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Nitta M, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(3):603–619. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou YH, Chu PC, Wu SW, et al. A systemic review and experts’ consensus for long-acting injectable antipsychotics in bipolar disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):121–128. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2015.13.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2 suppl):1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, Guillaume S, Lancrenon S, Samalin L. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brook RH, Chassin MR, Fink A, Solomon DH, Kosecoff J, Park RE. A method for the detailed assessment of the appropriateness of medical technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1986;2(1):53–63. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300002774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiden PJ, Preskorn SH, Fahnestock PA, et al. Roadmap Survey Translating the psychopharmacology of antipsychotics to individualized treatment for severe mental illness: a roadmap. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 7):1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiden P, Rapkin B, Zygmunt A, Mott T, Goldman D, Frances A. Postdischarge medication compliance of inpatients converted from an oral to a depot neuroleptic regimen. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46(10):1049–1054. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.10.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, Kahl KG, Holt RI, Moller HJ. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(6):412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al. International Society for Bipolar Disorders The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alphs L, Mao L, Lynn Starr H, Benson C. A pragmatic analysis comparing once-monthly paliperidone palmitate versus daily oral antipsychotic treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(2–3):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schreiner A, Aadamsoo K, Altamura AC, et al. Paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in recently diagnosed schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;169(1–3):393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822–829. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiden PJ, Roma RS, Velligan DI, Alphs L, DiChiara M, Davidson B. The challenge of offering long-acting antipsychotic therapies: a preliminary discourse analysis of psychiatrist recommendations for injectable therapy to patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):684–690. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacchetti E, Grunze H, Leucht S, Vita A. Long-acting injection antipsychotic medications in the management of schizophrenia. Evid Based Psychiatr Care. 2015;1:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICL) Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: Treatment and Management. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICL); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495–553. doi: 10.1177/0269881116636545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ketter TA. Acute and maintenance treatments for bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(4):e10. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13010tx2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor DM, Cornelius V, Smith L, Young AH. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of drug treatments for bipolar depression: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(6):452–469. doi: 10.1111/acps.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calabrese JR, Sanchez R, Jin N, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole once-monthly in the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 52-week randomized withdrawal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(3):324–331. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vieta E, Montgomery S, Sulaiman AH, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess prevention of mood episodes with risperidone long-acting injectable in patients with bipolar I disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(11):825–835. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quiroz JA, Yatham LN, Palumbo JM, Karcher K, Kushner S, Kusumakar V. Risperidone long-acting injectable monotherapy in the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(2):156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kane JM, Correll CU. The role of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):187–188. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, Huang C, Olfson M. Geographic and clinical variation in clozapine use in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):186–192. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Correll CU, Rubio JM, Inczedy-Farkas G, Birnbaum ML, Kane JM, Leucht S. Efficacy of 42 pharmacologic cotreatment strategies added to antipsychotic monotherapy in schizophrenia: systematic overview and quality appraisal of the meta-analytic evidence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):675–684. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostacher MJ, Tandon R, Suppes T. Florida best practice psychotherapeutic medication guidelines for adults with bipolar disorder: a novel, practical, patient-centered guide for clinicians. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(7):920–926. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15cs09841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galling B, Roldan A, Hagi K, et al. Antipsychotic augmentation vs. monotherapy in schizophrenia: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):77–89. doi: 10.1002/wps.20387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leucht S, Leucht C, Huhn M, et al. Sixty years of placebo-controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review, Bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(10):927–942. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16121358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malhi GS, Morris G, Hamilton A, Outhred T, Das P. Defining the role of SGAs in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(1):65–67. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, et al. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group consensus guidelines on diagnosis and terminology. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(3):216–229. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]