Abstract

Lung alveoli are lined by squamous alveolar epithelial type 1 (AT1) epithelial cells that facilitate gas exchange, and neighboring AT2 cells that synthesize and secrete surfactant. Alveoli are maintained by intermittent activation of rare ‘bifunctional’ AT2 cells that retain surfactant biosynthesis function but also serve as stem cells, generating new AT1 cells and self-renewing throughout adult life. While stem cell proliferation is controlled by EGFR/KRAS signaling, how the stem cells are selected, maintained, and the fates of their daughter cells controlled are unknown. Here we show that expression of the Wnt target gene Axin2 in mouse lung identifies a rare, stable subpopulation of AT2 cells with stem cell activity. Many lie near single fibroblasts that express Wnt5a and other Wnt genes, and genetically targeting Wnt secretion by fibroblasts depletes the Axin2+ AT2 stem cell population. Axin2 turns off when daughter cells leave the Wnt niche and transdifferentiate into AT1 cells, and sustaining Wnt signaling blocks transdifferentiation whereas abrogation of Wnt signaling promotes it, both in vivo and in vitro. Upon severe alveolar epithelial injury, Axin2 is induced throughout the AT2 population, recruiting ‘ancillary’ AT2 cells into a progenitor role. Niche expression of Wnt5a and the Wnt secretion mediator Porcupine is unchanged by injury, but Wnt7b and several other Wnt genes are broadly induced along with Porcupine in AT2 cells, and pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of this autocrine Wnt signaling impairs the AT2 proliferative response. The results support a model in which individual AT2 cells reside in single cell fibroblast niches that provide a short-range paracrine (or "juxtacrine") Wnt signal that selects and maintains alveolar stem cell identity and proliferative capacity, while severe injury induces AT2 autocrine Wnt signals that transiently expand the stem cell pool during repair.

Introduction

Although there has been great progress identifying adult tissue stem cells, much less is known about their niches and how niche signals control stem cell function and influence the fate of the daughter cells (1, 2). The best understood examples come from genetically tractable systems (3–5) such as Drosophila testis, where the niche is composed of 10–15 cells (“the hub”) that provide three short-range signals to the 5–10 germline stem cells they directly contact (6). These signals promote stem cell adhesion to the niche and inhibit their differentiation, but following polarized stem cell division the daughter cell that leaves the niche escapes these inhibitory signals and initiates the sperm differentiation program. In mammalian systems, stem cells and their niches are typically more complex, with more cells and/or more complex cellular interactions and dynamics. Even in the best-studied tissues such as blood (7), skin (8, 9), and intestine (10), there is still an incomplete understanding of niche cells, signals, and the specific aspects of stem cell behavior each signal controls. Here we describe what may be the simplest stem cell niche and control program, which maintains the gas exchange surface of the adult lung.

Genetic studies in mice support a hierarchy of adult stem cells that can replenish the alveolar gas exchange surface (11), some of which are active only following massive injury (12–14). Under normal homeostatic conditions, the alveolar epithelium is maintained by rare ‘bifunctional’ alveolar epithelial type 2 (AT2) cells, cuboidal cells that retain the surfactant biosynthesis and secretory function of standard ("bulk") AT2 cells (15) but also serve as stem cells that renew the alveolar epithelium throughout the lifespan (16, 17). Their intermittent activation gives rise to new AT1 cells, the exquisitely thin epithelial cells that mediate gas exchange, and generates clonal alveolar ‘renewal foci’ that progressively expand over time and together create ~7% new alveoli per year (16). Dying alveolar epithelial cells are proposed to provide a mitogenic signal transduced by the EGFR-KRAS pathway that triggers stem cell division (16). However, it is unclear how the stem cells are selected from bulk AT2 cells, how they are maintained throughout life, and how the fate of their daughter cells -- stem cell renewal vs. reprogramming to AT1 identity -- is controlled.

Here we molecularly identify alveolar stem cells as a rare subpopulation of AT2 cells with constitutive Wnt pathway activity, and show that specialized stromal fibroblasts located adjacent to the stem cells express Wnt5a and other Wnts and comprise a single cell Wnt signaling niche. We provide evidence that this short-range paracrine Wnt signal maintains the stem cell and controls the fate of its daughter cells. We also show that following severe epithelial injury, 'bulk' AT2 cells are recruited as ancillary stem cells, not by expanding the stromal Wnt signaling niche but by transiently inducing autocrine Wnt signaling by AT2 cells.

Results

The Wnt pathway gene Axin2 is expressed in a rare subset of AT2 cells

Molecular readouts of canonical Wnt signaling activity have identified stem cell populations in a variety of tissues (10), and the Wnt pathway has been shown to be active in developing alveolar progenitors (18–21). To determine if any AT2 cells in adult mice show active Wnt signaling, we examined AT2 cell expression of the Wnt target gene Axin2 (22) using an Axin2-Cre-ERT2 ‘knock-in’ allele (23) crossed to the Cre-dependent membrane GFP reporter Rosa26mTmG (24). After three daily injections of tamoxifen to induce Cre-ERT2 recombinase activity in Axin2-expressing cells at 2 months of age, FACS analysis showed that 1% of purified AT2 cells expressed the GFP reporter (Fig. 1d). Immunostaining for GFP and the canonical AT2 marker Surfactant protein C (SftpC) showed that the Axin2-Cre-ERT2 labeled AT2 cells were distributed sporadically throughout the lung (Fig. 1a–c). Multiplex single molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization for Axin2 and SftpC confirmed a minor population of Axin2-expressing (Axin2+) AT2 cells distributed throughout the lung (Fig. S1). The Axin2+ AT2 cells appear to represent a stable subpopulation because the percentage of AT2 cells labeled using Axin2-Cre-ERT2 did not increase when the daily tamoxifen injections were repeated one and two weeks after the initial induction, and the percentage was similar among adult animals induced at different ages (two and four months) (Fig. 1i). This AT2 cell subset expressed all extant markers of mature AT2 cells, including proteins and lipids associated with surfactant phospholipid production (Fig. S2), suggesting that the cells are physiologically functional. No marked AT1 or airway epithelial cells were detected under these "pulse-labeling" conditions (>1000 AT1 cells scored in each of 3 mice), although other (non-epithelial) alveolar cells also expressed Axin2 (see below). Thus, Axin2+ AT2 cells represent a rare and stable subpopulation of mature AT2 cells distributed throughout the alveolar region of the adult lung.

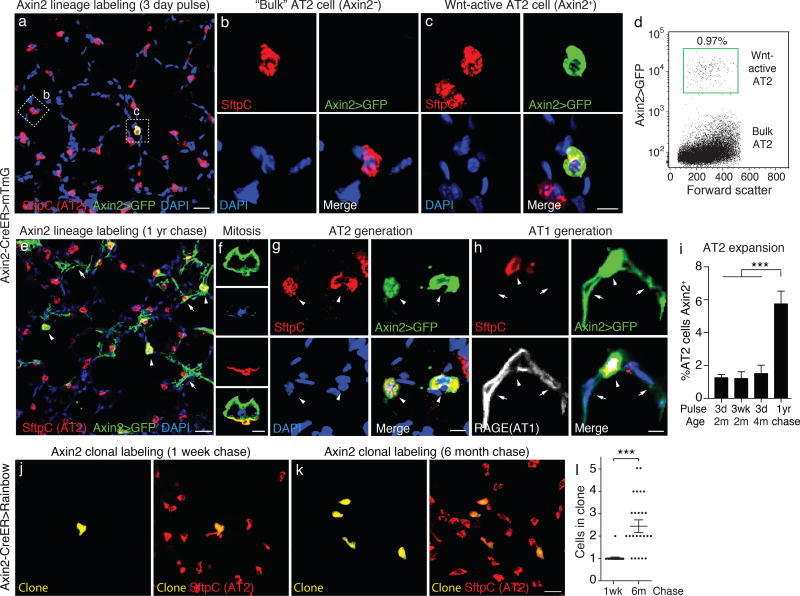

Figure 1. Wnt pathway gene Axin2 marks a rare population of AT2 cells with stem cell activity.

(a–c) Section through alveoli of adult (2 month old) Axin2-CreERT2;Rosa26-mTmG mouse lung immunostained for Cre recombinase reporter mGFP, AT2 cell marker pro-surfactant protein C (SftpC), and DAPI 5 days after 3 daily injections of 3 mg tamoxifen (3d "pulse") to induce CreERT2 and lineage label Axin2-expressing (Axin2+) cells (Axin2>GFP, green). Most AT2 cells ("bulk" AT2 cells) are Axin2- (box b in a, close up in b), but rare ones are Axin2+ (box c in a, close up in c) indicating activation by a Wnt signal ("Wnt-active"). (d) FACS analysis of AT2 cells from lungs as above. One percent of AT2 cells (1.0 ±0.5%, n=3 biological replicates) express Axin2>GFP. (e) Alveolar section from lungs lineage labeled as above but harvested one year after labeling ("1 yr chase"). Note expansion of Axin2-lineage AT2 cells (arrowheads) as well as AT1 cells and fibroblasts (arrows), the latter arising from a different Axin2+ cell lineage (Nabhan et al, unpublished). (f–h) Close-ups of lungs as in e showing Axin2+ lineage-labeled AT2 cells in mitosis (f) and after generating another AT2 cell (g, arrowheads) or AT1 cells (h, arrows). AT2 marker in f is apical surface protein Muc1 (red). AT1 marker in h is membrane protein RAGE (white). (i) Quantification of percent AT2 cells that are Axin2-lineage labeled immediately following a 3d pulse as above or a 3 week (3wk) pulse (3d pulse each week for 3 weeks) at age 2 months, a 3d pulse at 4 months, or after a 3d pulse at 2 months followed by 1 year chase ("1yr chase"). Values shown are mean ±SD (n=3500 AT2 cells scored in 2–4 biological replicates for each condition). (j,k) Alveolar sections of Axin2-CreERT2; Rosa26-Rainbow mice given limiting dose (2 mg) of tamoxifen at age 2 months to label isolated Axin2+ cells (j) with one of several Rainbow colors, and immunostained for SftpC (red) 1 week (j) or 6 months (k) later. (j) Isolated Axin2+ AT2 cell expressing mOrange clone marker (yellow) 1 week after labeling. (k) Four-cell clone 6 months later (k). (l) Quantification of AT2 clone sizes 1 week and 6 months after labeling. ***, p<0.001 (t test). Scale bars: 25 µm (a,e), 5 µm (b,c,fh), 20 µm (k).

Axin2+ AT2 cells have alveolar stem cell activity

To determine if the Axin2+ AT2 cells have stem cell activity, we followed the fate of the Axin2-Cre-ERT2 labeled AT2 cells during adult life by adding a half or full year "chase" (Fig. 1e–l). The labeled cells exhibited three principal features of stem cells (25). First, unlike most AT2 cells which are thought to be quiescent (26), 79% of Axin2+ AT2 cells labeled with a Cre-dependent Rainbow reporter (Fig. 1j) generated small clones of labeled cells (2.5 ±1.2 cells per clone for all labeled cells including singletons, 3.0 ±1.0 cells per clone for the 79% of labeled cells that generated clones, range 2 – 5 cells, n=24 Rainbow clones scored) in a six month period (Fig. 1k,l). Daughter cells remained local (Fig. 1k) with some found as doublets (Fig. 1g) that presumably represent instances of recent stem cell division (self-duplication); indeed, on occasion an Axin2+ AT2 cell was captured in the process of dividing (Fig. 1f), an intermediate we never observed for bulk AT2 cells in normal lungs. Second, there was a six-fold expansion of lineage-labeled AT2 cells relative to unlabeled cells during a one-year chase (Fig. 1i), indicating that the Axin2+ subset contributes substantially more to AT2 cell maintenance than Axin2-negative AT2 cells. Third, the labeled cells gave rise to another alveolar cell type, as shown by appearance over time of AT1 cells (flat RAGE+ SftpC- cells) expressing the lineage label (Fig. 1h). Like the AT2 daughter cells, daughter AT1 cells were typically found in close physical association with the presumed founder Axin2+ AT2 cell. We conclude that the Axin2+ cells constitute a rare subpopulation of AT2 cells with stem cell activity, which slowly (about once every 4 months) self-renew and produce new AT2 and AT1 cells during adult life.

Isolated fibroblasts expressing Wnt5a and other Wnts provide a short-range signal to neighboring AT2 stem cells

Because Wnt ligands are local signals with a typical range of just one or two cells (27), we presumed there must be a nearby Wnt source that continuously activates the Wnt pathway in the Axin2+ AT2 cells. Neighboring fibroblasts were an excellent candidate for the source because some share intimate physical connections with AT2 cells (28), such as Pdgfrα-expressing 'lipofibroblasts' that support their production of surfactant and formation of alveolospheres in culture (17, 29, 30). Indeed, we found that the transmembrane protein Porcupine (Porcn), which catalyzes fatty acylation of Wnts and promotes their secretion (31) and is a putative marker of Wnt signaling niches (32), was expressed in rare alveolar stromal cells (Fig. 2a), most of which were Pdgfrα-expressing fibroblasts (Fig. 2c) and at least some of which are found in close association with AT2 cells (Fig. 2b). Serial dosing of the Porcupine inhibitor C59 (4-(2-methyl-4-pyridinyl)-N-[4-(3-pyridinyl)phenyl]benzeneacetamide) reduced the pool of Axin2-expressing AT2 cells by 68% (Fig. 2d). Targeted deletion of Wntless, another transmembrane protein required for Wnt trafficking and secretion (33), in lung fibroblasts with TBXLME-Cre (34) or Pdgfrα-Cre-ER also reduced the pool of Axin2-expressing AT2 cells (Fig. 2e,f), confirming the role of PDGFRα-expressing fibroblasts as a source of secreted Wnts that maintains the Axin2+ AT2 stem cell pool. The remaining Axin2+ AT2 cells could be due to incomplete deletion or perdurance of Wntless in PDGFRα+ fibroblasts and/or to an alternate Wnt source, like the one induced by injury (see below).

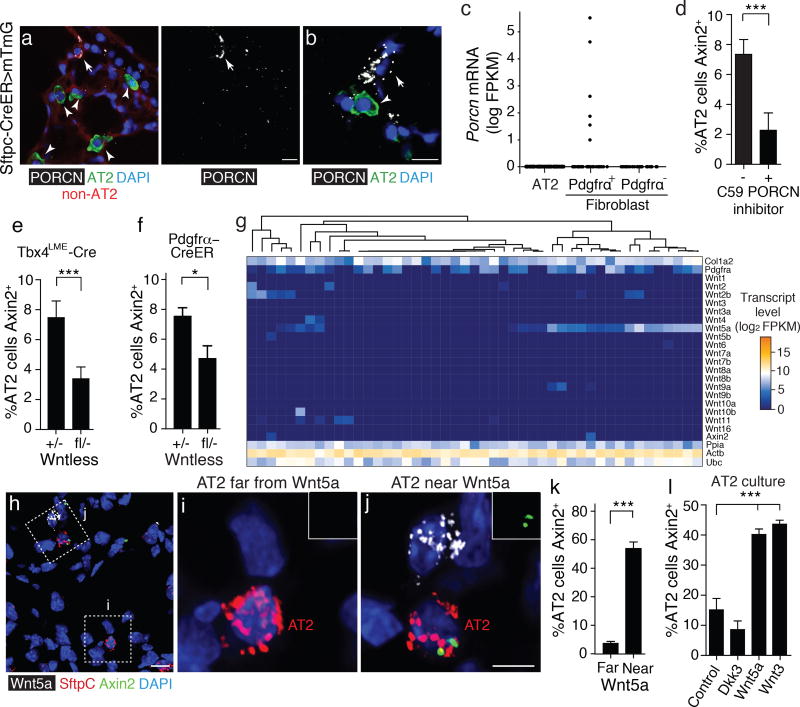

Figure 2. Single, Wnt-secreting fibroblasts comprise the AT2 stem cell niche.

(a,b) Alveolar sections of 2 month old adult Sftpc-CreER; Rosa26-mTmG lungs 1 week after induction with tamoxifen to label AT2 cells (green), and immunostained for Wnt secretion protein Porcupine (PORCN, white). Note rare stromal cells (non-AT2 cells, TdTomato+, red, arrow), but noAT2 cells (GFP+, green, arrowheads), expressing PORCN, some contacting AT2 cells (b). (c) Porcn mRNA levels determined by single cell RNAseq of adult lung fibroblasts and AT2 cells. A subpopulation of Pdgfrα-expressing fibroblasts express Porcn. Blue, DAPI. (d) Effect of 5 daily doses of PORC inhibitor C59 (+) or vehicle control (-) on Axin2-expresssion in AT2 cells at age 2 months, measured by multiplex single molecule proximity ligation in situ hybridization (PLISH) for Axin2 and Sftpc mRNA. Values shown are percentage (mean ±SD; of Sftpc-expressing AT2 cells that co- express Axin2 (n=900 AT2 cells scored in 3 biological replicates for each condition). ***, p=0.001 (t test). (e, f) Effect on Axin2-expresssion in AT2 cells by inhibiting fibroblast secretion of Wnts by conditional deletion of Wntless using lung mesenchyme driver Tbx4LME-Cre (e) or Pdgfrα-CreERT2 induced with 3 mg tamoxifen 3 days before analysis (f). *, p=0.02; ***, p=0.003 (t test). The Axin2+ AT2 cells remaining in the Wntless deletion conditions could be due to incomplete deletion (or perdurance) of Wntlessfl from fibroblasts, a Wnt signal provided by another cellular source (see below), or a Wntless-independent signal. (g) Expression of the 19 Wnt genes, fibroblast markers Pdgfrα and Col1a2, Axin2, and three ubiquitously-expressed control genes (Ubc, Ppla, Actb) (rows) in 47 alveolar fibroblasts (columns) isolated from wild type B6 adult lungs and analyzed by single cell RNA sequencing. Note subpopulation with robust expression of Wnt5a and lower expression of several other Wnt genes, and sporadic cells expressing other Wnt genes. Many Wnt5a-expressing fibroblasts co-express Pdgfrα. (h) Expression of Wnt5a, Axin2, and AT2 marker SftpC detected by PLISH in alveolar section of adult (2 month old) lung. Blue, DAPI. Note rare Wnt5a-expressing cell (box j). (i, j) Close up of boxed regions in h showing AT2 cell far from (i) or near (j) a Wnt5a-expressing cell. AT2 cell near Wnt5a source expresses Axin2 (green), indicating it is activated by the secreted signal; insets in i and j show Axin2 channel of the AT2 cell. (k) Quantification of data as in d–f showing percentage (mean ±SD) of AT2 cells located far from a Wnt5a source (>15 um, n=132 cells from 3 biological replicates) or near a Wnt5a source (<15 um, n=150 cells) that express Axin2. ***, p<0.0001 (t test). (l) Axin2 expression in AT2 cells isolated from adult Axin2-lacZ mice and cultured for 5 days with indicated Wnt proteins (Wnt5a, Wnt3) or antagonist Dickkopf3 (Dkk3) at 1ug/mL, then assayed with fluorogenic LacZ (beta-galactosidase) substrate Spider-gal. ***, p<0.0001 (t test). Scale bars: 10 µm (a, b, h) and 5 µm (j).

Single cell RNA sequencing of isolated alveolar fibroblasts revealed that a subset expressed Wnt5a, most of which (74%) also expressed PDGFRα (Fig. 2g). Many of the Wnt5a-expressing fibroblasts also expressed low levels of one or two other Wnt genes, including Wnt2 (see also ref (30)), Wnt2b, Wnt4, and Wnt9a, as did other smaller subpopulations of fibroblasts (Fig. 2g), whereas AT2 cells themselves did not express Porcupine (Fig. 2a) or any Wnt genes (Fig. S3), at least under normal conditions. Multiplexed single molecule in situ hybridization (35) demonstrated that Wnt5a-expressing fibroblasts (Fig. S4) are scattered throughout the alveolar region of the lung, most in close physical association or directly contacting an Axin2+ AT2 cell (Fig. 2h–k). Although Wnt5a protein is sufficient to induce Axin2 expression in AT2 cells (Fig. 2l), it is not the only Wnt ligand operative in vivo because other Wnts can also induce Axin2 (Fig. 2l), and conditional deletion of Wnt5a with Tbx4LME-Cre only reduced the number of Axin2+ AT2 cells in vivo by 15% and the effect did not reach statistical significance (p=0.12). We conclude that Wnt5a, along with the other Wnt ligands expressed by the fibroblasts, activate the canonical Wnt pathway in neighboring AT2 cells. This is a very short range signal, because AT1 daughter cells that derive from Axin2+ AT2 cells do not express Axin2 (n>1000 cells scored in 3 lungs at age 4 months), implying that they do not receive enough signal to maintain Axin2 expression once they move away from the Wnt source. Interestingly, some Wnt-expressing fibroblasts themselves (but not other nearby fibroblasts) expressed Axin2 (Figs. 2g, S4), suggesting that they may provide an autocrine signal as well.

Wnt signaling prevents reprogramming of alveolar stem cells into AT1 cells

To investigate the function of Wnt signaling in Axin2+ AT2 stem cells, we deleted β-catenin (36), a transducer of canonical Wnt pathway activity, in mature AT2 cells in vivo using a Lyz2-Cre knock-in allele (37) or an inducible SftpC-CreERT2 knock-in allele (12) while simultaneously marking recombined cells with the Rosa26mTmG Cre-reporter allele. We reasoned that only AT2 cells actively undergoing Wnt signaling (i.e., Axin2+ AT2 cells) would be affected by β-catenin deletion. The results showed a tripling in the number of AT1 cells (flat RAGE+ SftpC- cells) expressing the AT2 cell lineage mark (23±4% of all AT1 cells scored with Lyz2-Cre driver, vs 8±1.3% in wild-type β-catenin controls, n=100 random fields scored in 2 or 3 biological replicates), while preserving the percentage of lineage-labeled AT2 cells (85±3% of all AT2 cells scored vs 82±3% in wild-type β-catenin controls, n=500 AT2 cells scored in 3 biological replicates) and alveolar structure (Fig. 3a,b,d; Fig. S5a,b,d). Interestingly, 27% of the AT2 lineage-marked AT1 cells in this experiment (48 of 172 scored cells in 3 animals) were spatially isolated and not in physical association with a marked founder AT2 cell, implying that the stem cell had directly converted into an AT1 cell, a rare occurrence in control lungs (4%, n=145 scored cells in 3 biological replicates) (Fig. 3e,f, Fig. S5e,f). These results indicate that abrogation of constitutive Wnt signaling promotes differentiation ("transdifferentiation") of Axin2+ AT2 cells into AT1 cells.

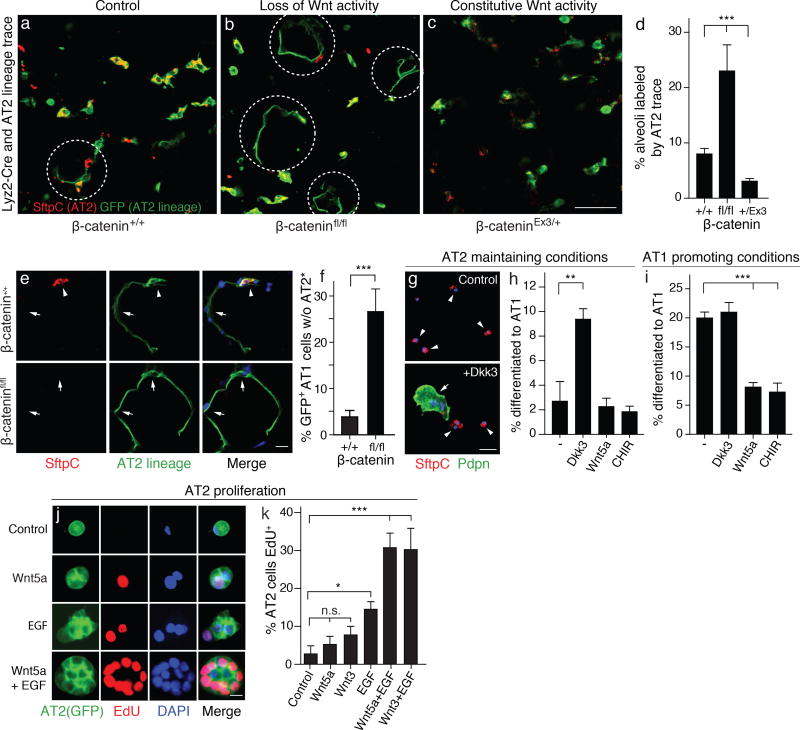

Figure 3. Wnt signaling maintains AT2 stem cells by preventing reprogramming to AT1 fate.

(a–d) Wnt regulation of reprogramming to AT1 fate. Alveolar sections of 8 month old adult Lyz2-Cre; Rosa26-mTmG (a, control), Lyz2-Cre; Rosa26-mTmG; β-cateninfl/fl (b, AT2 cell loss of Wnt activity), and Lyz2-Cre; Rosa26-mTmG; β-cateninEx3/+ (c, AT2 cell constitutive Wnt activity) immunostained for AT2 marker SftpC (red) and Lyz2-Cre (AT2 marker) lineage trace (mGFP, green). Lyz2-Cre turns on in mature AT2 cells (16). Dashed circles, alveolar renewal foci identified by squamous AT1 cells that arise from AT2 stem cells and express AT2 lineage trace. Note increased reprogramming to AT1 fate when β-catenin is deleted to eliminate Wnt signaling (b), and decreased reprogramming when β-catenin exon3 (Ex3) is deleted to constitutively activate Wnt signaling (c). Scale bar, 50 µm. Quantification (d) shows percent (mean ±SD) of alveoli with AT2 lineage-labeled AT1 cells (n=25 100µm z-stacks scored in 2 or 3 biological replicates for each condition). ***, p=0.002 (Kruskal-Wallis test). (e,f) Deletion of β-catenin results in loss of AT2 stem cells during reprogramming to AT1 fate. Close up of renewal foci (e) as above in wild type β-catenin control (Lyz2-Cre; β-catenin+/+, upper panels) and β-catenin conditional deletion (Lyz2-Cre; β-cateninfl/fl, bottom panels) lungs. Note AT1 cell (arrow) and its AT2 parent cell (open arrowhead) in control focus, and absence of AT2 parent cell (*) in β-catenin-deleted focus, implying loss of stem cell by direct reprogramming (without self renewal) to AT1 fate. Quantification (f) shows percentage (mean ±SD) of AT1 cells derived from AT2 lineage (GFP+) that lack a parent AT2 cell. ***, p=0.0004 (t test). (g–i) Wnt signaling prevents reprogramming to AT1 fate in culture. AT2 cells isolated from wild type (B6) adult mouse lungs were cultured under AT2-maintaining conditions (Matrigel, minimal media, 1% FBS, FGF-7; g,h) or AT1 promoting conditions (poly-lysine coated glass, minimal media, 10% FBS; i) without (control) or with the indicated Wnt pathway antagonists (0.15 ug/ml Dkk3) or agonists (0.1 ug/ml Wnt5a or 10 nM CHIR99201, a canonical Wnt pathway activator). After 4 days of culture, cells were immunostained for SftpC (red) and Podoplanin (green) (g) and the percentage (mean ±SD) of AT2 cells (small, cuboidal SftpC+; arrowheads) and AT1 cells (large, squamous, Podoplanin+; arrow) quantified (n=500 cells from 3 biological replicates for each culture condition) (h,i) **, p=0.002; ***, p<0.001 (t test). (j, k) AT2 cells isolated from 2 month old Sftpc-CreER; Rosa26-mTmG adults were cultured as above (AT2-maintaining conditions, g) without (control) or with indicated Wnt proteins (at 100 ng/mL) and/or EGF (at 50 ng/mL), then proliferation measured by incorporation of synthetic nucleotide EdU. Quantification in k (n= 400 cells scored per condition, 4 biological replicates). * p=0.007, ***; p<0.001 (t test). n.s., not significant. Scale bars: 50 µm (c, g), 10 µm (e), 5 µm (j).

We also tested the consequence of preventing AT2 cells from downregulating canonical Wnt signaling by using Lyz2-Cre and SftpC-Cre-ERT2-rtTA to express a stabilized allele of β-catenin (β-cateninEx3) (38). This did not induce significant proliferation (Fig. S6) or any other obvious phenotypic effect on AT2 cells, but reduced by 2.7-fold the number of lineage-marked AT1 cells compared to wild type β-catenin controls (Fig. 3c,d, Fig. S5c,d,g). Together, these results suggest that Wnt signaling maintains Axin2+ AT2 stem cells by preventing their differentiation into AT1 cells.

Studies of cultured AT2 cells support the in vivo results. Under culture conditions that promote maintenance of the AT2 cell phenotype (39), addition of the Wnt antagonist Dickkopf 3 (Dkk3) (40) increased by 3.8-fold the percentage of cells that reprogrammed to AT1 identity (2.5±1.5% vs. 9.5±0.1% with Dkk3) (Fig. 3g,h). Conversely, under conditions that promote differentiation into an AT1 fate (39), addition of recombinant Wnt5a inhibited this transdifferentiation 2.6-fold (21±1% vs 8±1% with Wnt5a) (Fig. 3i). CHIR99021, a pharmacological activator of canonical Wnt signaling (41), had a similar effect as Wnt5a (3-fold inhibition of transdifferentiation, 7±1%).

Thus, canonical Wnt signaling maintains the AT2 stem cell pool by preventing their reprogramming to AT1 identity, both in vivo and in vitro. Although Wnt signaling on its own had little effect on AT2 proliferation in vivo (Fig. S6) or in culture (Fig. 3j,k), it enhanced the mitogenic activity of EGF (Fig. 3j,k), an important result we return to in the Discussion.

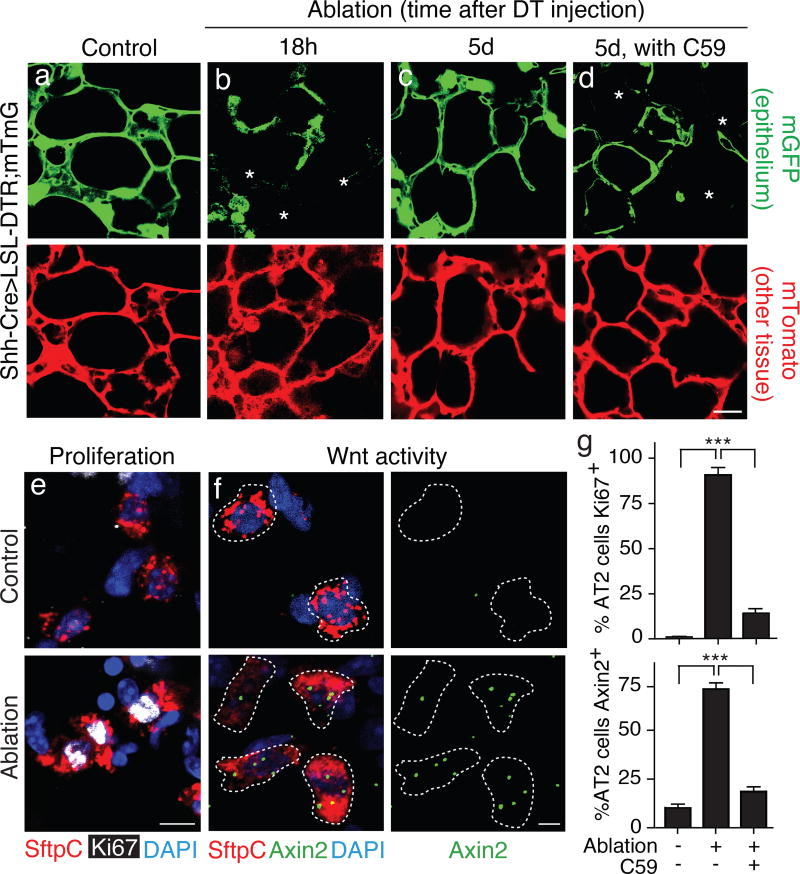

Wnt signaling is induced in and required for progenitor activity of ‘ancillary’ AT2 stem cells following epithelial injury

To investigate the activity of alveolar stem cells following injury, we established a genetic system to induce alveolar epithelial cell death. Human diphtheria toxin receptor was expressed throughout the lung epithelium of adult mice using a Shh-Cre driver (42, 43). Diphtheria toxin (DT, 150 ng) was then administered, triggering apoptosis in ~40% of alveolar epithelial cells (Fig. 4a,b) but sparing enough cells for epithelial repair (Fig. 4c) and the animal's survival. Staining for the proliferation marker Ki67 under these conditions revealed that nearly all (85%) of the surviving AT2 cells began proliferating after injury (Fig. 4e,g), indicating that 'bulk' AT2 cells that do not function as stem cells during normal aging are recruited to serve as ‘ancillary’ progenitors to rapidly repair epithelial damage. Recruitment of bulk AT2 cells as ancillary progenitors is also observed following hyperoxic alveolar injury (44, 45) (see below). Most AT2 cells (73%) expressed Axin2 following DT-triggered injury, indicating that canonical Wnt signaling is broadly induced in the ancillary AT2 stem cells (Fig. 4f,g). Inhibition of Wnt signaling by administering Porcupine inhibitor C59 abrogated AT2 cell proliferation and blocked alveolar epithelial repair (Fig. 4d,g). Thus, in addition to its role in maintaining Axin2+ AT2 cells during normal aging, Wnt signaling recruits ancillary AT2 cells with progenitor capacity following severe epithelial injury.

Figure 4. Epithelial injury induces ancillary Axin2-expressing AT2 cells in alveolar repair.

(a–d) System for genetically-targeted acute epithelial injury. Shh-Cre drives expression of Diptheria toxin receptor (DTR) and mGFP transgenes throughout epithelium; sporadic epithelial cell death ("ablation") is induced by injecting limiting dose (150 ng) of Diptheria toxin (DT). mGFP (upper panels) and mTomato (lower panels) micrographs of the same dual-labeled alveolar section of adult Shh-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-DTR/Rosa26-mTmG lungs18 hours after vehicle (a, control) or DT injection (b), or 5d after DT injection without (c) or with (d) Porcn inhibitor C59 to block Wnt secretion. Disruption of alveolar epithelium (mGFP, upper panels) is apparent at 18 hrs after DT injection (b, asterisks), and epithelial repair nearly complete at 5 days (c). Blocking Wnt secretion inhibits repair (d, asterisks). Other alveolar tissues (mTomato, lower panels) remain intact. (e–g) Effect of epithelial injury on proliferation and Wnt signaling in AT2 cells. Alveolar sections of Shh-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-DTR animals injected with vehicle (control, upper panels) or DT (ablation, lower panels) as above and immunostained for AT2 marker SftpC (red) and proliferation marker Ki67 (white) (e), or probed by PLISH for SftpC (red) and Axin2 (green) expression (f) five days after injury. DAPI, blue. Quantification (g) (n=250 cells in 4 animals for each condition) of percentage of AT2 cells that express Ki67 (mean ±S.D, upper plot) or Axin2 (mean ±S.D, lower plot). Epithelial ablation induces proliferation and Wnt pathway activation in most AT2 cells, and both effects are abrogated by Wnt secretion inhibitor C59. ***, p<0.001 for each comparison indicated (t test). Scale bars: 25 µm (d), 10 µm (e) 5 µm (f).

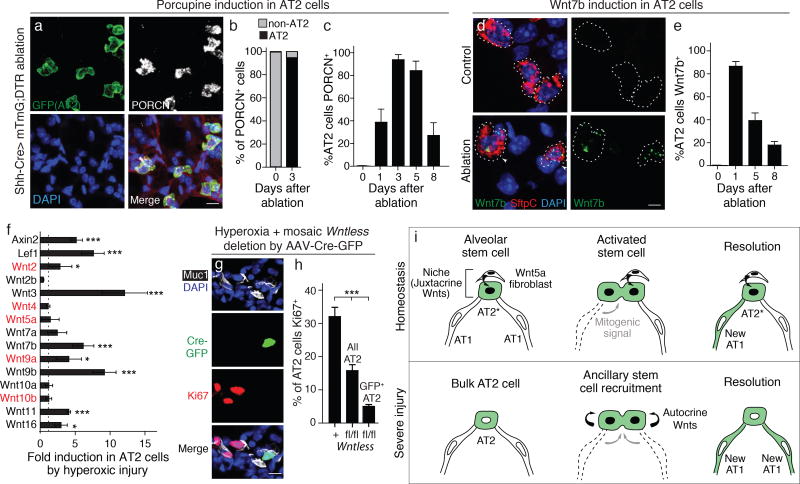

Injury induces autocrine signaling in AT2 cells by a suite of Wnts

We tested whether the expanded pool of Axin2+ AT2 cells following DT-triggered epithelial injury was due to expansion of the stromal Wnt signaling centers. Multiplex in situ hybridization and immunostaining demonstrated no accompanying change in Wnt5a expression (Fig. S7c) or stromal expression of Porcupine (Fig. 5a,b), respectively. By contrast, Porcupine was broadly induced in AT2 cells (Fig. 5a–c), suggesting that injury activates an autocrine Wnt signal. Indeed, we found that Wnt7b, which is expressed in epithelial progenitors during alveolar development (19, 46) but not in healthy adult AT2 cells (Fig. S3), was broadly induced in AT2 cells following DT-triggered injury (Fig. 5d,e). A time course of repair (Fig. S7) showed that AT2 expression of Wnt7b and Porcupine, and activation of canonical Wnt signaling measured by Axin2 expression, were induced within 24 hours of injury (Fig. 5c,e, Fig. S7). AT2 proliferation initiated over the next two days and peaked at day 5 as epithelial integrity was restored, after which AT2 cell proliferation and gene expression returned toward baseline and new AT1 cells began to appear (Fig. S7).

Figure 5. Epithelial injury induces autocrine Wnt signaling in bulk AT2 cells.

(a) Alveolar sections immunostained as indicated from 2 month old Shh-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-DTR/Rosa26-mTmG mouse 3 days after DT injection to induce sporadic epithelial ablation. Note AT2 cells (cuboidal GFP+ cells), but not other cells, express Porcupine (PORCN, white). (b,c) Quantifications showing percentage of PORCN+ cells that are AT2 cells, before and 3d after ablation (b) (n=200 scored PORCN+ cells in 3 mice per condition), and percentage (mean ±SD) of AT2 cells expressing PORCN at indicated time after ablation (c) (n=500 scored AT2 cells in 4 mice per time point). (d) Alveolar sections of Shh-Cre; Rosa26LSL-DTR animals probed by PLISH for Wnt7b (green) and SftpC (red) 1 day after injection with vehicle (Control) or DT (Ablation). DAPI, blue. Ablation induces Wnt7b expression by AT2 cells. (e) Quantification showing time course of induction of Wnt7b expression by AT2 cells following ablation (n=300 AT2 cells scored per animal, 4 biological replicates per time point, mean ±S.D). ***, p<0.001 (t test) for both comparisons indicated. (f) mRNA induction of indicated Wnt genes and Wnt pathway target genes (Axin2, Lef1) measured by qRT-PCR of lineage-labeled AT2 cells sorted from mice before (control) and 2d after hyperoxic alveolar injury (5d at 75% O2) (see scheme in Fig. S8b). Values shown are fold mRNA induction relative to control (mean ±SD, n=3 mice per condition). A suite of Wnt genes is induced in AT2 cells, most of them different from the Wnt genes expressed by the fibroblast niche cells under control conditions (highlighted red; see Fig. 2g). Dashed line, control value. *, p< 0.05, ***, p<0.001 (g,h) Function of autocrine Wnt signaling in AT2 cell proliferative response following hyperoxic alveolar injury. Alveolar section immunostained as indicated from adult (2 month old) Wntlessfl/fl mouse with alveolar epithelium infected with AAV9-GFP-Cre virus (Fig. S8d–f) to mosaically delete Wntless from AT2 cells (to prevent autocrine Wnt secretion) 1 week before hyperoxic injury. Note proliferation (Ki67 staining, red) of AT2 cells (Muc1 apical surface marker, white) induced by hyperoxic injury (see Fig. S8a), but not AT2 cell infected with AAV-Cre-GFP (green) to delete Wntless. (h) Quantification of g, showing percentage of AT2 cells that were Ki67+ following hyperoxic alveolar injury to AAV9-Cre-GFP-infected control (Wntless+/+) and Wntlessfl/fl mice, scored for all or just GFP+ (AAV9-Cre-GFP-infected) AT2 cells. Values shown are mean ±SD (n=500 AT2 cells scored per mouse, 3 mice per condition, except only 52 GFP+ cells were scored in Wntlessfl/fl because they were rare). Note almost complete elimination of proliferative response in GFP+ AT2 cells, implying key role for autocrine Wnt signaling in their proliferative response to injury. (j) Model of alveolar stem cells and their niche. During homeostasis (top), the niche is composed of a single fibroblast constitutively expressing Wnt5a and/or other Wnt genes (Fig. 2g) that provide a "juxtacrine" signal (arrow) to the neighboring AT2 cell (green cytoplasm indicating lineage trace label, black nucleus indicating Wnt signal reception and Axin2 induction), selecting and maintaining it as a stem cell (left panel). Upon receiving a mitogenic signal from a dying AT1 cell (middle panel), the activated stem cell proliferates and the two daughter cells (green) compete for the niche. One remains in the niche as the stem cell (stem cell renewal). The other leaves niche, losing the Wnt signal and disinhibiting the AT1 differentiation program (stem cell reprogramming) to form a new AT1 cell (right panel). Although bulk AT2 cells are normally quiescent (bottom left panel), following acute epithelial injury bulk AT2 cells are recruited as "ancillary stem cells" by induction of autocrine Wnt signaling by a different suite of Wnts including Wnt7b (middle panel), which allows unlimited proliferation in response to mitogenic signaling from dying cells. Autocrine Wnt signaling diminishes as the epithelial injury resolves (right panel). Scale bars: 10um (a, g), 5um (d).

To explore the generality and function of injury-induced autocrine Wnt signaling, we used a hyperoxic alveolar injury model (75% oxygen) to induce the repair program (44) (Fig. S8a). This allowed us to mark, isolate, and genetically manipulate alveolar epithelial cells by endotracheal delivery of an adeno-associated virus encoding a Cre recombinase (AAV9-Cre) into the lungs of mice carrying a Cre-dependent reporter gene and conditional Wnt pathway alleles. qPCR analysis of FACS-purified, lineage-labeled AT2 cells (Fig. S8b,c) showed that hyperoxic injury induced AT2 cell expression of Wnt7b and at least six other Wnt genes by 3 to 12-fold, and similarly increased Axin2 (5-fold) and Lef1 (7-fold) expression, indicating autocrine activation of the canonical Wnt pathway (Fig. 5f). Interestingly, the suite of Wnt genes induced by injury did not include most of the Wnt genes expressed by the fibroblast niche including Wnt5a (Fig. 5f, Wnt genes in red). AAV9-Cre-mediated mosaic deletion of Wntless in ~50% of alveolar epithelial cells (Fig. S8d–f) to prevent Wnt secretion reduced the number of proliferating (Ki67+) AT2 cells following injury (Fig. 5h). The effect was cell autonomous because AT2 cells expressing high levels of Cre-GFP, but not neighboring control AT2 cells, showed diminished proliferation (Fig. 5g,h). Like the paracrine fibroblast niche, this autocrine effect is likely mediated by multiple Wnts because deletion of just one of the highly induced Wnt genes (Wnt7b) did not diminish proliferation. We conclude that epithelial injury induces AT2 cell expression of a suite of Wnt genes that provide an autocrine Wnt signal, which transiently endows bulk AT2 cells with progenitor cell function and proliferative capacity during repair.

Discussion

We have molecularly identified and characterized a rare subset of mature AT2 cells with stem cell function that are scattered throughout the mouse lung in specialized niches that renew the alveolar epithelium throughout adult life. These isolated stem cells (AT2stem) are marked by continuous expression of the Wnt target gene Axin2, and many lie near single fibroblasts that express Wnt5a and other Wnt genes that serve as a paracrine Wnt signaling niche (Fig. 5i). The stem cells divide intermittently, self-renewing and giving rise to daughter AT1 cells that lose Wnt pathway activity after they exit the niche. Maintaining canonical Wnt signaling blocked transdifferentiation to AT1 cells, whereas loss or antagonism of Wnt signaling promoted it.

Our results support a model in which each Wnt-expressing fibroblast defines a stem cell niche accommodating a single AT2stem, due to the short-range paracrine Wnt signal, and this "juxtacrine" signal serves to select and maintain AT2stem identity (Fig. 5i). When an AT2stem divides, daughter cells compete for the niche. The one that remains in the niche continues to receive the Wnt signal and retains AT2stem identity, whereas the one that leaves the niche escapes the signal and reprograms to AT1 fate. Daughter cells leaving the niche can also become standard surfactant-secreting AT2 cells, if they land near a mesenchymal signaling center that selects and maintains bulk AT2 fate (Brownfield et al, in preparation). This streamlined stem cell niche, the simplest conceivable comprising perhaps just a single Wnt-expressing fibroblast and the stem cell it supports, minimizes impact of the niche on the gas exchange function of the alveolus. It also explains why the growing foci of new alveoli are clonal, derived from a single AT2stem mother cell that typically remains associated with the niche and its growing focus throughout life (16). Although our model posits that the niche cell selects the stem cell, it remains uncertain how and when the niche cells -- scattered throughout the alveolar interstitium of the lung -- are selected. Some niche cells themselves are Axin2+ (Figs. 2g, S4; see also reference (30)), suggesting that autocrine Wnt signaling might maintain the niche as the paracrine signal maintains the stem cell within it.

Our results also reveal a dramatic expansion of the alveolar stem/progenitor population in the face of severe epithelial injury, when the rare AT2stem are insufficient to replace lost cells. Under these conditions, many 'bulk' AT2 cells that are normally quiescent turn on Axin2 and are recruited as ancillary alveolar stem cells that rapidly proliferate and regenerate the lost AT1 and AT2 cells (Fig. 5i). This widespread recruitment of bulk AT2 cells to AT2stem function is not achieved by expansion of Wnt5a or Porcupine expression among fibroblasts. Rather, injury induces expression in AT2 cells of Porcupine and a different suite of Wnt genes including Wnt7b. This switch to autocrine control of stem cell identity following injury obviates dependence on the stromal niche. As the injury resolves and the alveolar epithelium is restored, Wnt expression subsides in ancillary AT2stem and they cease proliferating and begin differentiating into AT1 cells or returning to their bulk AT2 identity. The Wnt pathway has also recently been found to be broadly active during alveolar development (19, 20) and in cancer (see below), where most cells proliferate, so Wnt signaling may have a general role in maintaining alveolar progenitor and stem cell states.

Our data suggest that Wnt signaling to mature AT2 cells, whether paracrine Wnts from the fibroblast niche or autocrine Wnts induced by injury, endows them with two stem cell properties. One is induction and maintenance of AT2stem gene expression and identity, preventing spontaneous reprogramming from AT2stem to AT1 (and presumably bulk AT2) fate, as occurred when Wnt signaling was abrogated (Fig. 3). The other is an ability to proliferate extensively and perhaps indefinitely, as observed following epithelial injury when the ancillary AT2stem divide rapidly to restore the epithelium, an effect abolished by Wnt inhibition (Fig. 5). Thus, Wnt signaling confers stem cell identity and capability ("stemness") on AT2 cells, but does not itself activate the stem cells; indeed, driving constitutive Wnt signaling in AT2stem in vivo (Fig. S6), or adding Wnt ligands in vitro (Fig. 3j,k), induced little proliferation. Stem cell proliferation is proposed to be controlled by the EGFR/KRAS mitogenic signaling pathway in AT2stem (16) (Fig. 3j,k), triggered by EGF ligand(s) induced by injury (47). We propose here that Wnt and EGFR/KRAS signaling pathways function in parallel to select/maintain and activate alveolar stem cells, respectively, explaining their observed synergy (Fig. 3j,k).

The above findings could have important implications for lung adenocarcinoma, the leading cancer killer (48). Adenocarcinoma is initiated by oncogenic mutations that constitutively activate the EGFR/KRAS pathway in AT2 cells (16, 49, 50). Although most AT2 cells show a limited proliferative response following expression of oncogenic KRAS, a rare subset continues proliferating indefinitely and forms deadly tumors (16). Recently, Porcupine, Wnt expression, and Wnt pathway activation were found to mark a subpopulation of cells in lung adenocarcinoma that are proposed to comprise the lung cancer stem cell and its niche (51). We speculate that the tumor-initiating cells are AT2stem, and the niche signal is provided by the Wnt-expressing stromal fibroblasts and/or an autocrine Wnt signal secreted by the tumor cells themselves, as in the AT2 injury response. As oncogenic KRAS drives stem cell proliferation, Wnt signaling would maintain stem cell identity and the capacity to proliferate indefinitely. This would explain why Wnt signaling has little proliferative or oncogenic activity on its own but robustly potentiates KRASG12D and BRAFV600E mouse models of lung carcinogenesis, and why inhibition of Wnt signaling in both models induces tumor senescence (51–53). If this idea is correct, then Wnt pathway antagonists should be a powerful adjuvant to EGFR antagonists in treatment of EGFR-activated adenocarcinomas, attacking stem cell identity as well as activity and thereby halting proliferation while simultaneously reprogramming the stem cells to benign AT1 or bulk AT2 states. One reason that alveolar stem cell activity may have restricted during evolution to a minor pool of AT2 cells (AT2stem) is that it reduces the number of cells susceptible to oncogenic transformation.

There is growing appreciation that some mature cell types in adult tissues can provide stem cell function (54–58). However, like AT2stem their clinical potential has been largely overlooked as more classical "undifferentiated" and pluripotent tissue stem cells have been sought. Our study shows that stem cells and their niche cells can each represent minor, solitary subsets of the mature cell types in an organ. But by molecularly identifying these rare subpopulations and the endogenous niche signals and mechanisms, as we have done for AT2stem, it should be possible to prospectively isolate and expand them for regenerative medicine.

Methods

Mouse strains

C57BL/6 (abbreviated B6; Jackson Laboratories) was the wild type strain. Expression of Cre recombinase or estrogen-inducible Cre recombinase (Cre-ERT2) for conditional cell- and tissue-specific manipulation of gene expression in vivo used gene-targeted Cre alleles Axin2-Cre-ERT2(23), Lyz2 (also called LysM)-Cre(37), Shh-Cre-EGFP (42), SftpC-Cre-ERT2-rtTA (12) and Pdgfrα-Cre-ERT2 (59). Cre-dependent target genes used were the conditional "floxed" alleles: β-cateninfl/fl for inactivation (36) and β-cateninEx3 for activation of canonical Wnt signaling(38), Wntlessfl to prevent Wnt secretion (60), Rosa26iDTR for diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) expression for cell ablation (43) and the Cre reporters Rosa26-mTmG, which expresses membrane-targeted GFP (mGFP) following Cre-mediated recombination and mTomato in all other tissues (24), and Rainbow, where all cells express eGFP before recombination and switch to permanent expression of one of mCerulean, mCherry or mOrange after recombination (61). Induction of Cre-ERT2 conditional alleles was done by intraperitoneal injection of 3 mg tamoxifen once a day for three days, except where noted. Vehicle control injections of Axin2 Cre-ERT2;R26mTmG animals gave no background labeling of lung cells. All mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Stanford University.

Immunostaining, microscopy, and histological scoring

Lungs were collected as previously described (16). After inflation, lungs were removed en bloc, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking, then either cryo-embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT, Sakura) or sectioned (350 um slices) using a vibrating microtome (Leica). Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (62) using primary antibodies raised against the following epitopes and used at the indicated dilutions: pro-SftpC (rabbit, Chemicon AB3786, 1:250), GFP (chicken, Abcam AB13970, 1:500), RAGE (rat, R&D MAB1179, 1:250), E-cadherin (rat, Life Technologies 131900 clone ECCD-2, 1:100), Podoplanin (Pdpn, hamster, DSHB 8.1.1, 1:20), Aquaporin 5 (Aqp5, rabbit, Calbiochem 178615, 1:500), Mucin 1 (Muc1, hamster, Thermo Scientific HM1630, clone MH1, 1:250), Ki67 (rat, DAKO M7249, clone TEC-3, 1:100), Lamellar associated membrane protein (Lamp-1, Rat, DSHB 1D4B, 1:250), Lamp-2 (rat, DSHB GL2A7, 1:250), Hopx (rabbit, Abcam ab10625, 1:250) and Porcupine (rabbit, Abcam ab105543, 1:200). Primary antibodies were detected with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) unless otherwise noted. LipidTOX deep red neutral lipid stain (Life Technologies/Thermo-Fisher) was used at 1:200. Stained specimens were placed in #1 coverglass chambers (LabTEK), mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (5 ug/ml, Vector labs), and images acquired with a laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscope (Zeiss LSM780) and processed with ImageJ.

In situ hybridization

Multiplexed single molecule in situ hybridization of mRNAs was performed by proximity ligation in situ hybridization (PLISH) (35), in which OCT-embedded, cryopreserved tissue sections are hybridized with anti-sense probe pairs that anneal at adjacent positions in a tiled manner along a target transcript. Probe pairs targeting each mRNA share a barcoded sequence complementary to bridge and circle constructs that after annealing undergo proximity ligation to form a closed circle that undergoes rolling circle amplification. Each circle encodes a 'landing pad' specific for detection oligonucleotides conjugated to a distinct fluorophore, generating discrete puncta for each transcript that can be spectrally resolved for multiplexing. The following sets of primer pairs were used to detect transcripts of the indicated genes:

Axin2

-

5’TAGCGCTAACAACTTACGTCGTTATGATTTCGTGGCTGTTGCGTA3’

5’TTTCATTTTCCTTCAGAATTTATACGTCGAGTTGAACGTCGTAACA3’

-

5’TAGCGCTAACAACTTACGTCGTTATGAGCTGTGCCAAAGTGTTGG3’

5’CCTGCGGCAGGCTTCCTCTTTATACGTCGAGTTGAACGTCGTAACA3’

-

5’TAGCGCTAACAACTTACGTCGTTATGAGTGGTGGTGAACGTGCT3’

5’ACAGCGTGGTGGTGGATGTTTATACGTCGAGTTGAACGTCGTAACA3’

-

5’TCAACTCGACGTATAACATAACGACGTAAGTAACACGGCGCTACTCATGGT3’

5’ATCTGGAAGGAGAGTCACTTTATACGTCGAGTTGAACGTCGTAACA 3’

Pdgfra

-

5’TCGTACGTCTAACTTACGTCGTTATGAAAGGCCCCAAATTCAGAA

5’TCCTGATAGCCTACCACCTTTATACGTCGAGTTGAAGAACAACCTG

-

5’TCGTACGTCTAACTTACGTCGTTATGTTCTAGCCCCGTTCCAAAT

5’GCCTTCCTGCATGGTTGACTTATACGTCGAGTTGAAGAACAACCTG

-

5’TCGTACGTCTAACTTACGTCGTTATGAACGTGCCTGTGGGGAATA

5’ATTCAAAAGTGCAACAGTTTTATACGTCGAGTTGAAGAACAACCTG

SftpC

-

5’TCGTACGTCTAACTTACGTCGTTATGTGCGGTTTCTACCGACC

5’GGTCTTTCCTGTCCCGCTTATACGTCGAGTTGAAGAACAACCTG

Wnt2b

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGATCAACACGTCCCTAGGGC

5’CCTCCTAAATCCATCCCCTTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGAAGTCGATCGTGGAACGTG

5’GAGAGAACCTTCCCTGTTTTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGAAATCTGCCTCTGTGGCCA

5’ATTAGTCCTATCATCCAAATTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGACGGTATCAGTGATGGCATT

5’GGGCGAGAACATCCAAGTTTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

Wnt5a

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGATTTCGTGGCTGTTGCGTAG

5’GTTTCATTTTCCTTCAGAATTTATACGTCGAGTTGAACGTCGTAACA

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGAAGCCTTGGGGGACAAT

5’TCAAGCGAAGCGTCGGGGTTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGACTGTCCTACGGCCTGCTT

5’TACATCTGCCAGGTTGTATTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGATGTGGTGAGCTGGTTTGC

5’ATTGTTTAAACTAGCTATCTTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

Wnt7b

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGAACCACCTCTCTCCCCCA

5’TGCCCTGCCTGGGTCCACTTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGATCAGCCCTGGCAGTTTCT

5’TAGGCTGTGGGCAGTTGTATTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGAGGTCTGGCTACCCAGTCG

5’AGGGTGTCCTCAAATAGGGTTTTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

-

5’GACGCTAATAGACTTACGTCGTTATGTGTCCCTGACCTCTCCTGA

5’ATCTGTCATGTGGGGCAATTATACGTCGAGTTGATAGACACTCTT

Wnt9b

-

TGGGTGTGAACCATGAGAAGTATGACAACAGCCTCAAGATCATC

GATGATCTTGAGGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGGTTCACACCCA

Following PLISH, expression was detected by fluorescence microscopy as tiny (~0.5 µm) puncta of fluorescence, each representing a single RNA molecule. PLISH (Fig.S1) was more sensitive than the fluorescent (mGFP) genetic (Axin2-CreERT2;Rosa26-mTmG) reporter (Fig. 1a–d) at detecting Axin2+ AT2 cells, and indeed we confirmed by single cell RNA sequencing of GFPAT2 cells that Axin2-CreERT2;Rosa26-mTmG does not label all Axin2+ AT2 cells.

For in situ mRNA detection using a proprietary high sensitivity RNA amplification and detection technology (RNAscope, Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark CA), paraffin-embedded lung sections (15 um) were processed for in situ detection using proprietary probes for Axin2 and SftpC RNA and the RNAscope 2-plex Detection Kit (chromogenic), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Lineage tracing and clonal analysis

For AT2 lineage tracing, Lyz2-Cre; Rosa26mTmG mice, or SftpC-Cre-ERT2-rtTA; Rosa26mTmG mice induced by intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen, were used to permanently turn on expression of mGFP in AT2 cells. At the indicated ages or times after labeling, AT2 cell-derived AT1 cells were quantified by scoring in a blinded fashion 100 random alveolar fields (Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 25× objective, field size ~ 120 um2) for AT1 cells labeled with the AT2 lineage label mGFP, with each alveolus assumed to contain two AT1 cells as previously described (16). To determine the frequency of AT2-cell derived AT1 cells that had lost the parent AT2 cell, benzyl alcohol benzyl benzoate (BABB)-cleared 350 um lung slices from 8 month old animals were examined, and foci of AT1 cells expressing the AT2 lineage label mGFP in random fields (Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 63× objective, field size ~ 70 um2) were scored for a neighboring founder AT2 cell; those lacking one were considered 'parentless.'

For clonal analysis of Axin2+ AT2 cells, Axin2-Cre-ERT2;Rosa26-Rainbow mice were administered a limiting dose of tamoxifen (2 mg) by intraperitoneal injection at age 2 months (PN60d) to sparsely label Axin2-Cre-ERT2- expressing cells with one of the three Rainbow fluorescent reporter proteins. After one week or six months to allow proliferation of labeled cells, lungs were collected, immunostained for SftpC and then an anti-rabbit Alexa-647 labeled secondary, and cleared as described above. Left lobes were sectioned (250 um slices) with a Leica vibratome and imaged. Clones were scored as clusters of cells expressing the same fluorescent reporter localized within 20 um of each other. Under the sparse labeling conditions, cells from different clones were never observed to intermingle, implying restricted dispersion of daughter cells.

FACS sorting and marker expression analysis of Axin2+ AT2 cells

For FACS quantification of Axin2+ AT2 cells, single cell suspensions of AT2 cells were prepared as described below from tamoxifen-induced Axin2-Cre-ERT2; Rosa26mTmG, then stained with an Allophyocyanin (APC)-conjugated EPCAM antibody (Ebiosciences; 1:50) for 30 minutes and DAPI at 0.1 ug/ml (to exclude dead cells) and analyzed for GFP, EPCAM, and DAPI fluorescence by FACS (Aria II; BD Biosciences). Littermates with no tamoxifen injection were used as control. To analyze AT2 marker expression in Axin2+ AT2 cells, cDNA was prepared from sorted single Axin2+ AT2 cells and control Axin2- AT2 cells and ciliated cells using Smartseq2 protocol (Clonetech). Quality and concentration of cDNA was determined on a Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical) and sequencing libraries were constructed (Illumina Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation Kit) from cells with high quality cDNA. Single-cell libraries were then pooled and sequenced 2 × 150 base pair paired end reads to a depth of 2 ×106 reads per cell on an Illumina NextSeq500 instrument using Illumina NextSeq high-output kit. Reads were aligned and quantified as transcripts per kilobase million (TPM) using Kallisto.

Genetically targeted lung epithelial cell ablation

Epithelial cell ablation was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of 150 ng of Diphtheria toxin (DT; R&D) in sterile PBS (250 ul) into adult Shh-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-DTR mice, which express Diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) throughout the airway and alveolar epithelium. This dose of DT was found in preliminary titration experiments to induce sporadic cell death ('ablation') of ~40% alveolar epithelial cells. To inhibit Wnt secretion and signaling during the repair process, the Porcupine inhibitor C59 (Tocris) was administered by oral gavage at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight every twelve hours for 5 days beginning 5 minutes before DT injection. C59 was prepared in a solution of 0.5% methyl cellulose/0.1% Tween 80 that was sonicated for 20 minutes immediately prior to administration.

Hyperoxic alveolar injury and Wnt gene induction in AT2 cells

Two to three months old mice were housed in a sealed chamber equipped with an oxygen controller (ProOx 110, Biospherix) with medical grade 100% O2 delivered continuously to maintain chamber O2 levels at 75% to injure the alveolar epithelium; O2 levels above 75% were not used because they caused over 50% mortality. After 5 days at 75% O2, mice were returned to room air to initiate repair. Two days later, lungs were harvested and analyzed by immunostaining for alveolar markers and the cell proliferation marker Ki67 as described above.

To identify Wnt genes induced in AT2 cells by hyperoxic injury, mGFP+ AT2 cells were purified by FACS from lungs of tamoxifen-induced, AT2 lineage-labeled SftpC-CreERT2; Rosa26mTmG mice injured by hyperoxia as above, or from uninjured control mice processed in parallel. cDNA libraries were prepared by Smartseq2 protocol (63) from 1000 FACS-sorted GFP+ AT2 cells from each lung and from 1000 control GFP- cells. After dilution to equalize cDNA concentrations between samples, qPCR was performed for the genes indicated below on 50–100 ng cDNA with 1 uM forward and reverse primers and SYBER Green I reagents (Invitrogen) using an ABI 7900HT real-time PCR system (Invitrogen – Life Technologies). qPCR was performed in triplicate for each biological sample and fold enrichment was calculated from Ct values for each gene of interest, normalized to expression of housekeeping genes Gapdh and Actb, using Microsoft Excel and PRISM. Purity of sorted AT2 cells was confirmed by enrichment in expression of AT2 marker Sftpc in sorted GFP+ cells vs sorted control GFP- cells (Fig. S8c).

qPCR primers:

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Gapdh | 5’-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3’ | 5’-ACACATTGGGGGTAGGAACA-3’ |

| SftpC | 5'-AGC AAA GAG GTC CTG ATG GA-3' | 5'-GAG CAG AGC CCC TAC AAT CA-3' |

| Wnt2 | 5’-GCTGAGTGGACTGCAGAGTG-3 | 5’-ACTTCCAGCCTTCTCCAGGT-3’ |

| Wn3 | 5’-TTTGGAGGAATGGTCTCTCG-3’ | 5’-ACCACCAGCAGGTCTTCACT-3’ |

| Wnt5a | 5’-CTGGCAGGACTTTCTCAAGG-3’ | 5’-GTCTCTCGGCTGCCTATTTG-3’ |

| Wnt7a | 5’-AGGAGCTCAAAGTGGGGAGT-3’ | 5’-TGGTACTGGCCTTGCTTCTC-3’ |

| Wnt7b | 5’-TCCGAGTAGGGAGTCGAGAG-3’ | 5’-CCTTCCGCCTGGTTGTAGTA-3’ |

| Wnt10a | 5’-CCGAGGTTTTCGAGAGAGTG-3’ 5 | 5’-AACCGCAAGCCTTCAGTTTA-3’ |

| Wnt10b | 5’-TTCTCTCGGGATTTCTTGGA-3’ | 5’-CACTTCCGCTTCAGGTTTTC-3’ |

| Wnt11 | 5’-ACCTGCTTGACCTGGAGAGA-3’ | 5’-AGCCCGTAGCTGAGGTTGT-3’ |

| Wnt16 | 5’-TGATGTCCAGTACGGCATGT-3’ | 5’-CAGGTTTTCACAGCACAGGA-3’ |

| Wnt4 | 5’-CGAGGAGTGCCAATACCAGT-3’ | 5’-GTCACAGCCACACTTCTCCA-3’ |

| Wnt2b | 5’-TTGTGTCAACGCCTACCCAGA-3’ | 5’-ACCACTCCTGCTGACGAGAT-3’ |

| Wnt9a | 5’-CCCCTGACTATCCTCCCTCT-3’ | 5’-GATGGCGTAGAGGAAAGCAG-3’ |

| Wnt9b | 5’-GGGTGTGTGTGGTGACAATC-3’ | 5’-TCCAACAGGTACGAACAGCA-3’ |

| Axin2 | 5’-ACTGGGTCGCTTCTCTTGAA-3’ | 5’-CTCCCCACCTTGAATGAAGA-3’ |

| Lef1 | 5’-TGAAGCCTCAACACGAACAG-3’ | 5’-GCCCAGGATCTGGTTGATAG-3’ |

AAV-Cre virus-mediated gene deletion in alveolar epithelium

AAV9-Cre-GFP is a recombinant adeno-associated virus with a CMV promoter driving expression of a Cre-GFP fusion protein. Viral particles (1×1013 GC/ml, from Vector Labs #7100 or University of Pennsylvania Viral Core) were diluted 1:5 in RPMI medium, and then 50 uL of the diluted virus preparation were delivered endotracheally into the lungs of isoflurane anesthetized adult mice carrying a Cre-dependent conditional allele of Wntless (Wntlessfl/fl). Infected alveolar cells were identified by GFP fluorescence; infection was specific for the alveolar epithelium, with ~50% of AT2 cells infected under the described conditions (see Fig. S8f).

AT2 cell isolation and culture

Peripheral lung cells were isolated from 2 month old B6 mice (Jackson laboratories) as previously described (39). Mice were euthanized with CO2 and lung vasculature perfused through the right ventricle with 37°C media (DMEM, 10% FBS). The trachea was punctured and lungs inflated with digestion buffer (media, 1mg/ml elastase (Worthington), 10% dextran (Sigma)) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Lungs were then removed and the lobes separated, minced and digested with DNase (200 µg/ml; Sigma) for 5 minutes at 37°C. The resulting cell suspensions were filtered first through a 100 um then 40 um filter. AT2 cells in the flow-through were enriched by negative selection against CD31, CD45 and Pdgfrα (Miltenyi), followed by positive selection for EPCAM on a magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) MS selection column (Miltenyi). The isolated AT2 cells (>95% purity) were cultured in 8-well #1 coverglass chambers (Labtek) under AT1-promoting conditions (DMEM/F12 media with 10% FBS on glass) or AT2-maintaining conditions (1% FBS, 10 ng/ml FGF7, 50 µg/ml Penicillin and Streptomycin, on growth-factor-reduced Matrigel (BD)) as previously described (16, 39) in a 10% CO2/air incubator for five days at 37°C with daily replacement of medium. Wnt3a(R&D), Wnt5a (R&D), Dkk3 (R&D), Egf (R&D) and CHIR99201 (Sigma) were added to cultures at the concentrations indicated, 3 hours after plating to allow cell attachment. To detect AT2 proliferation in vitro, EdU was added to the culture medium to a concentration of 10uM. Following a 24 hour incubation period, cells were fixed and EdU incorporation visualized using a Click It EdU Detection Kit (Fisher) following immunostaining as described above.

Single-cell RNA sequencing of lung fibroblasts to identify Wnt-expressing cells

Isolation, single cell RNA sequencing, and analysis of adult mouse AT2 cells was done as described (16, 64). Isolation, sequencing, and analysis of alveolar fibroblasts was done similarly and will be detailed elsewhere (Brownfield et al, in preparation). Briefly, peripheral lung cells were obtained from adult mouse lungs, and the single-cell suspension was incubated with a cell viability stain and antibodies to fluorescently label leukocytes (anti-CD45), endothelial (anti-Pecam), and epithelial (anti-EpCAM, eBioscience) cells. Viable CD45- Pecam- EpCAM- cells were sorted into DMEM containing 10% FBS, and sorted cells were stained with a cell viability marker and loaded onto a medium-size (10–17 µm cell diameter) microfluidic Fluidigm C1 RNA-seq chip. Captured cells were imaged to assess number and viability of cells per capture site. Sequencing libraries were constructed (Illumina Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation kit) (65), and single-cell libraries pooled and sequenced 100 base pairs (bp) paired-end to a depth of (2–6)×106 reads. Sequencing data were processed as described (64), and transcript levels quantified as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) generated by TopHat/Cufflinks. Cells not expressing (FPKM < 1) three of four housekeeping genes (Actb, Gapdh, Ubc, Ppia) or expressing them less than three standard deviations below the mean, were removed from the analysis. Fibroblasts were identified as cells expressing canonical fibroblast markers Mgp, Col1a1, and Col1a2 that also lacked expression of canonical markers of the major airway or alveolar epithelial cell types (64). Subsequent analysis including hierarchical clustering was performed as described (64).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis and statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism software. Replicate experiments were all biological replicates with different animals, and quantitative values are presented as mean ±S.D. Student’s t-tests were two-sided. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size, and data distribution was assumed to be normal. Both male and female animals were used in experiments, and subjects were age- and gender-matched in biological replicates and in comparisons of different groups.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. A subpopulation of AT2 cells detected by single molecule in situ hybridization to Axin2. (a) Alveolar section of 2 month old wild type B6 adult mouse lung probed for RNA expression of AT2 cell marker Sftpc (red) and Axin2 (green) by multiplex single molecule proximity ligation in situ hybridization (PLISH). DAPI, blue. (b) Close-up of box b. Most AT2 cells ("bulk" AT2 cells), like one shown, do not express Axin2. (c) Close-up of box c showing rare AT2 cell that expresses Axin2, indicating activation by a Wnt signal. (d) Similar alveolar section probed for Axin2 (red, colorimetric amplification that also fluoresces red) and Sftpc mRNA (cyan, colorimetric amplification only) using RNAscope in situ hybridization and amplification. Fluorescent (upper panel) and brightfield (lower panel) images of same alveolar section are shown. Like PLISH, RNAscope detects bulk Sftpc-expressing AT2 cells (lower left cell) and a rare subpopulation of Wnt-active AT2 cells that express both Sftpc and Axin2 (upper right cell). Scale bars, 10 µm (a), 5µm (c,d).

Figure S2. Axin2-expressing AT2 cells express mature AT2 cell markers. Alveolar sections (a,d,g) of 2 month old lungs from Axin2-CreERT2; Rosa26-mTmG mouse lung immunostained for Cre reporter mGFP (Axin2>GFP, green) and mature AT2 markers (red) Lamp1 (a), Lamp2 (b), and neutral lipid stain LipidTOX (c) 5 days after 3 daily injections of 3 mg tamoxifen to activate CreERT2. Close-ups of boxed regions show AT2 marker expression in a bulk AT2 cell (b,e,h) and an Axin2-expressing (Axin2+) AT2 cell (c,f,i). Axin2+ AT2 cells express mature AT2 markers and accumulate lipids like bulk AT2 cells. DAPI, blue. (j) Heat map showing RNA expression levels of eGFP and tdTomato (tdT) transgenes, 11 canonical AT2 genes, and 2 canonical ciliated cell genes (Foxj1, Cdc113) (rows) in individual, flow-sorted Axin2>GFP+ AT2 cells (n=58), control Axin2>GFP- AT2 cells (n=24), and control ciliated airway cells (n=22) (columns) from lungs of 2 month old adult Axin2-CreERT2; Rosa26-mTmG mice. Note similar expression profiles of canonical AT2 markers in Axin2-GFP+ and Axin2-GFP- AT2 cells. Scale bars, 20 um (a,d,g), 5 µm (b,c,e,f,h,i).

Figure S3. Single cell RNA sequencing shows AT2 cells do not normally express Wnt genes. Expression of the 19 Wnt genes, AT2 markers SftpC and Lyz2, and three ubiquitously-expressed control genes (Ubc, Ppla, Actb) (rows) in 44 AT2 cells (columns) isolated from wild type B6 adult lungs and analyzed by single cell RNA sequencing (64). Note absence of Wnt gene expression in AT2 cells, in contrast to a similar analysis of alveolar fibroblasts that showed robust expression of Wnt5a and several other Wnt genes (Fig. 2b).

Figure S4. Expression of an alveolar fibroblast marker and Wnt target gene in Wnt5a-expressing alveolar cell. Close-up of an isolated Wnt5a-expressing cell in an alveolar section of 2 month old wild type B6 adult mouse lung probed by PLISH for RNA expression of Wnt5a (white), alveolar fibroblast marker Pdgfrα (red), and Wnt target gene Axin2 (green). All three markers are co-expressed by the same cell, confirming that it is a Pdgfrα+ alveolar fibroblast (Fig. 2b) that is apparently activated by the Wnt5a signal it expresses. Scale bar, 2 µm.

Figure S5. Effect of manipulating canonical Wnt pathway activity in mature AT2 cells in vivo using Sftpc-CreER transgene. Alveolar sections of 10 month old adult Sftpc-CreER; Rosa26-mTmG (a, control), Sftpc-CreER; Rosa26-mTmG; β-cateninfl/fl (b, AT2 cell loss of Wnt activity), and Sftpc-CreER; Rosa26-mTmG; β-cateninEx3/+ (c, AT2 cell constitutive Wnt activity) lungs immunostained for AT2 marker SftpC (red) and AT2 lineage trace (mGFP, green) 8 months after 3 daily injections of 3 mg tamoxifen to induce CreER in AT2 cells. Dashed circles, alveolar renewal foci identified by squamous AT1 cells that arise from AT2 stem cells and express AT2 lineage trace. Note increased reprogramming to AT1 fate when β-catenin is deleted to eliminate Wnt signaling (b), and decreased reprogramming when β-catenin exon3 (Ex3) is deleted to constitutively activate Wnt signaling (c), similar to results obtained using Lyz2-Cre AT2 cell driver (Fig. 3a-c). Quantification (d) shows percent (mean ±SD) of alveoli with AT2 lineage-labeled AT1 cells (n=60 100 µm thick z-stacks scored in 3 biological replicates of each genotype). **, p=0.021 (Kruskal-Wallis test). Close-ups of alveolar sections as above immunostained for AT2 marker (SftpC, red), AT2 cell lineage trace (mGFP, green), and AT1 marker (RAGE, white). Flat cells expressing AT2 lineage trace (arrows) are RAGE+ SftpC-, indicating transdifferentiation to AT1 identity; note lineage-labeled AT2 cells (arrowheads) in e and f, but absence of lineage-labeled AT2 cell in f, suggesting that founder AT2 stem cell transdifferentiated into an AT1 cell. Scale bars, 50 µm (c), 10 µm (g).

Figure S6. Effect of constitutive Wnt pathway activation on AT2 cell proliferation in vivo. Alveolar sections of 8 month old adult Lyz2-Cre; Rosa26-mTmG (a, control) and Lyz2-Cre; Rosa26-mTmG; β-cateninEx3/+ lungs with constitutive Wnt pathway activation in AT2 cells (b) immunostained for AT2 marker SftpC (red), AT2 cell lineage trace mGFP (Lyz2>GFP, green), and cell proliferative marker Ki67 (white). Note same number of AT2 cells in each field, and a rare proliferating AT2 cell (arrowhead) in b. (c) Quantification of a and b showing similar number of AT2 cells (mean ±S.D) per 25× field of view (~130 um2) (n=200 fields scored in 3 biological replicates of each genotype). n.s., not significant (p=0.58, t test). (d) Quantification of a and b showing percentage of AT2 cells (mean ±S.D) expressing proliferation marker Ki67 (n=900 AT2 cells scored in 3 biological replicates of each genotype). Note small (1.7%) but not statistically significant (n.s.; p=0.08, t test) effect of constitutive Wnt pathway activation (beta-cateninEx3). Scale bar, 10 µm.

Figure S7. Time course of cellular and molecular changes in AT2 cells during alveolar regeneration following genetically-targeted epithelial ablation. (a) Time course of AT2 cell proliferation following targeted epithelial ablation. Alveolar sections of 2 month old adult Shh-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-DTR mouse mock-injected with phosphate-buffered saline (day 0 control), or injected with 200 ng DT to induce partial (~40%) epithelial ablation and then analyzed by immunostaining for AT2 apical marker Muc1 (green) and cell proliferation marker Ki67 (red) at indicated times after ablation. DAPI, blue. Open arrowheads, quiescent AT2 cells; filled arrowheads, proliferating AT2 cells. No proliferative AT2 cells are observed before injury, but almost all AT2 cells are proliferating at day 5, before returning to quiescence by day 8. (b) Close-ups of normal AT2 cell (top row, arrowhead) and AT2 cells differentiating toward AT1 fate (middle and bottom rows) 5 days after ablation as in a, as shown by immunostaining for AT2 apical marker Muc1 (green), AT1 nuclear marker Hopx (red) and basal surface marker RAGE (white), counterstained with DAPI (blue). Middle row shows AT2 cell (arrowhead) expressing AT2 marker Muc1 that has turned on AT1 transcription factor Hopx. Bottom row shows similar AT2 cell (arrowhead) that has also begun to flatten toward AT1-like morphology and turned on AT1 marker RAGE (white, basal). (c) Quantification of cellular and molecular events during alveolar regeneration following targeted epithelial ablation as in a and b. Top graph shows quantification of number of Wnt5a RNA-expressing cells (mean ±S.D) assayed by PLISH (see Fig. 2h) in each 25× field (n=100 fields, 4 biological replicates per time point) at indicated times after DT injection to induce epithelial ablation. Note Wnt5a expression is not affected by ablation. Other plots show changes following ablation in percentage (mean ±S.D) of AT2 cells that express Wnt7b RNA (see Fig. 5e; n=300 scored AT2 cells per mouse, 4 biological replicates per time point), Porcupine protein (see Fig. 5c; n=500 scored AT2 cells per mouse, 4 biological replicates per condition), Axin2 RNA (Fig. 4f,g; n=300 scored AT2 cells per mouse, 4 biological replicats per time point), and Ki67 protein (see Fig. 4e,g; n=500 scored AT2 cells per mouse, 4 biological replicates per condition), and % AT2 cells with flat, AT1-like morphology (n=200 scored Muc1+ AT2 cells per mouse, 4 biological replicates per condition). Scale bars, 10 µM (a,b).

Figure S8. Experimental schemes for analyzing induction of autocrine Wnt signaling in AT2 cells following alveolar injury and its role in repair. (a) Effect of hyperoxic alveolar injury on AT2 cell proliferation. Alveolar section of 2 month old adult B6 mouse following 5 days of hyperoxia (75% O2) and two day recovery, immunostained for AT2 marker Muc1 (red) and proliferative marker Ki67 (white), and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Approximately 30% of AT2 cells are induced to proliferate (arrowheads) by the injury. (b) Schematic of approach to characterize induction of Wnt gene expression in AT2 cells following hyperoxic injury. SftpC-CreERT2; R26-mTmG animals are injected with tamoxifen (3 mg) to lineage label AT2 cells. One week later, mice are placed in sealed chamber maintained at 75% O2 for 5 days to induce alveolar injury. After two days of recovery in atmospheric O2 to initiate regeneration, lungs are harvested and GFP+ AT2 cells and control GFP- cells are purified by FACS, and expression of Wnt genes, Wnt target genes, and AT2 markers is analyzed in each population by qRT-PCR. (c) qRT-PCR of AT2 marker Sftpc RNA in GFP+ and GFP- cells shows dramatic (>20,000-fold) enrichment in GFP+ cells, confirming purity of AT2 cells. Results for Wnt genes and Wnt targets are given in Fig. 5f. (d) Experimental scheme for analyzing role of autocrine Wnt signaling in alveolar repair. Recombinant adeno-associated virus AAV9-Cre-GFP was delivered intratracheally to lungs of Wntlessfl/fl mice (or Wntless+/+ mice as control). After 14 days to allow viral infection and Cre-mediated deletion of Wntless in AT2 cells to prevent their secretion of Wnts, mice were subjected to hyperoxic alveolar injury as above. After 2 day recovery, the proliferative response of infected (GFP+) and uninfected AT2 cells (GFP-) was analyzed (see Fig. 5g,h). (e,f) Assessment of AAV9-Cre-GFP targeting selectivity (e) and AT2 cell infection efficiency (f). Lung section of 2 month old adult Rosa26-mTmG that received an intratracheal AAV-9-Cre-GFP as above, then immunostained 12 days later for AT2 marker Muc1 (which also marks airway epithelium) and GFP to show infected cells. Low magnification (e) shows AAV9-Cre-GFP infection selectively in alveolar region (Alv), not bronchi (Br). High magnification of alveolar region (f) shows some infected AT2 cells (filled arrowheads) whereas others are not (open arrowheads). Quantification (n=500 scored AT2 cells per mouse, 3 biological replicates) shows that 50 ±11% of AT2 cells are infected with the AAV9-Cre-GFP virus under these conditions. Scale bars: 100 µm (e), 20 µm (f).

Figure S9. RNAscope validation of in situ results. Alveolar sections of adult Shh-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-DTR/Rosa26-mTmG lungs 5 days after vehicle (a, control) or DT injection (b) to ablate ~40% of epithelial cells. Sections were probed for SftpC RNA (cyan in left colorimetric images) or Axin2 RNA (red in left colorimetric images and fluorescent image of same tissue on right) by RNAscope dual color in situ hybridization. Note increase in Axin2+ SftpC+ cells, as well as in some other (unidentified) cells after ablation. Scale bar, 5 um.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andres Andalon for technical assistance; Barbara Treutlein and Stephen Quake for help with single cell RNA sequencing; Roel Nusse and colleagues for generously sharing mouse lines and reagents; members of the Krasnow, Desai, and Nusse labs for discussion; and Maria Peterson for help preparing the manuscript and figures. This work was supported by an NHLBI U01 Progenitor Cell Biology Consortium grant (M.A.K., T.J.D.), NHLBI 1R56HL1274701 (T.J.D.), and Stanford BIO-X IIP-130 (T.J.D.). A.N.N. was supported by NIH CMB training grant fellowship 2T32GM007276, and M.A.K is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The data reported in this paper will be tabulated in the Supporting Online Material and expression-profiling data sets will be deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

ANN, TD and MAK designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. All experiments except fibroblast and AT2 single cell RNA sequencing were performed and analyzed by ANN. DB performed and analyzed single cell RNA sequencing of alveolar fibroblasts and AT2 cells.

References and Notes

- 1.Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008;132:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scadden DT. Nice neighborhood: emerging concepts of the stem cell niche. Cell. 2014;157:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuller MT, Spradling AC. Male and female Drosophila germline stem cells: two versions of immortality. Science. 2007;316:402–404. doi: 10.1126/science.1140861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrd DT, Kimble J. Scratching the niche that controls Caenorhabditis elegans germline stem cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:1107–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Losick VP, Morris LX, Fox DT, Spradling A. Drosophila stem cell niches: a decade of discovery suggests a unified view of stem cell regulation. Dev Cell. 2011;21:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Cuevas M, Matunis EL. The stem cell niche: lessons from the Drosophila testis. Development. 2011;138:2861–2869. doi: 10.1242/dev.056242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison SJ, Scadden DT. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;505:327–334. doi: 10.1038/nature12984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rompolas P, Greco V. Stem cell dynamics in the hair follicle niche. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2014;25–26:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu YC, Li L, Fuchs E. Emerging interactions between skin stem cells and their niches. Nat Med. 2014;20:847–856. doi: 10.1038/nm.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clevers H, Loh KM, Nusse R. Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science. 2014;346:1248012. doi: 10.1126/science.1248012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Logan CY, Desai TJ. Keeping it together: Pulmonary alveoli are maintained by a hierarchy of cellular programs. Bioessays. 2015;37:1028–1037. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman HA, et al. Integrin alpha6beta4 identifies an adult distal lung epithelial population with regenerative potential in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2855–2862. doi: 10.1172/JCI57673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar PA, et al. Distal airway stem cells yield alveoli in vitro and during lung regeneration following H1N1 influenza infection. Cell. 2011;147:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray S, et al. Rare SOX2+ airway progenitor cells generate KRT5+ cells that repopulate damaged alveolar parenchyma following influenza virus Infection. Stem Cell Reports. 2016;7:817–825. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitsett JA, Wert SE, Weaver TE. Alveolar surfactant homeostasis and the pathogenesis of pulmonary disease. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:105–119. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.041807.123500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desai TJ, Brownfield DG, Krasnow MA. Alveolar progenitor and stem cells in lung development, renewal and cancer. Nature. 2014;507:190–194. doi: 10.1038/nature12930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barkauskas CE, et al. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3025–3036. doi: 10.1172/JCI68782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mucenski ML, et al. beta-Catenin is required for specification of proximal/distal cell fate during lung morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40231–40238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajagopal J, et al. Wnt7b stimulates embryonic lung growth by coordinately increasing the replication of epithelium and mesenchyme. Development. 2008;135:1625–1634. doi: 10.1242/dev.015495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank DB, et al. Emergence of a wave of Wnt signaling that regulates lung alveologenesis by controlling epithelial self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2312–2325. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okubo T, Hogan BL. Hyperactive Wnt signaling changes the developmental potential of embryonic lung endoderm. J Biol. 2004;3:11. doi: 10.1186/jbiol3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jho EH, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1172–1183. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1172-1183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Amerongen R, Bowman AN, Nusse R. Developmental stage and time dictate the fate of Wnt/beta-catenin-responsive stem cells in the mammary gland. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lajtha LG. Stem cell concepts. Differentiation. 1979;14:23–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1979.tb01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messier B, Leblond CP. Cell proliferation and migration as revealed by radioautography after injection of thymidine-H3 into male rats and mice. Am J Anat. 1960;106:247–285. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farin HF, et al. Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem-cell niche. Nature. 2016;530:340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature16937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]