Abstract

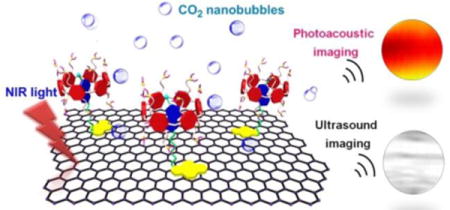

Photoacoustic imaging combines the merits of ultrasound imaging and optical imaging that allows a fascinating imaging paradigm with deeper tissue penetration than optical imaging and higher spatial resolution than ultrasound imaging. Herein, we develop a supramolecular hybrid material composed of graphene oxide (GO) and a pillar[6]arene-based host–guest complex (CP6⊃PyN), which can be used as a ultrasound (US) and photoacoustic (PA) signal nanoamplifier. Triggered by the near-infrared (NIR) light mediated photothermal effect, CO2 nanobubbles are generated on the surface of GO@CP6⊃PyN due to the decomposition of bicarbonate counterions, thus strongly amplifying its US and PA performances. Our study, for the first time, demonstrates enhanced US and PA activity in supramolecular hybrid material on the basis of host–guest chemistry as a photoacoustic nanoplatform.

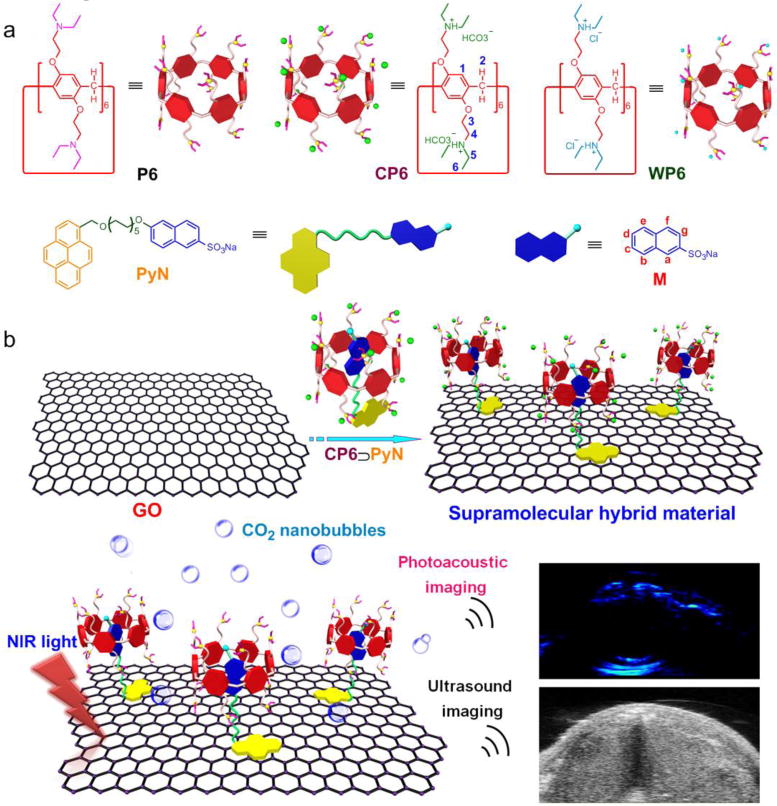

Graphical abstract

A supramolecular hybrid material is developed using graphene oxide and a pillar[6]arene-based host–guest complex as building blocks, which can be used as a ultrasound and photoacoustic signals nanoamplifier by fully taking advantages of supramolecular chemistry. Our study paves a distinctive way to fabricate smart nanomaterials for imaging-guided theranostic applications.

Photoacoustic (PA) imaging depends on the detection of ultrasonic waves generated by thermo-elastic expansion, which combines the advantages of both ultrasound and optical imaging.1–3 Compared with most optical imaging techniques, PA imaging provides extraordinary opportunities for monitoring and detecting disease pathophysiology in vivo benefiting from its capacity for high-resolution imaging of rich optical contrast at depths beyond the optical transport mean-free-paths. Efficient contrasts are urgently needed for excellent-performance PA imaging, of which the PA signal amplitude is determined by optical-to-acoustic conversion efficiency, including the light absorption and the conversion from absorbed laser energy to an outgoing thermoacoustic wave.4–6

Ascribing to their unique chemical, physical and mechanical properties, graphene and its derivatives have attracted tremendous interest for applications ranging from energy, electronics, materials science to biomedicine. Among various graphene derivatives, graphene oxide (GO) has been extensively studied in biomedical applications such as bioassays, biosensors and drug delivery, arising from their easy preparation, high water solubility, excellent biocompatibility, low toxicity and ultrahigh drug loading efficiency.7–10 For example, GO has been widely utilized as a drug delivery vehicle to load hydrophobic drugs through π–π stacking and hydrophobic interactions between GO and the drugs.11–13 Photothermal-activated drug release can be achieved in vitro and in vivo by taking advantage of the near-infrared (NIR) light-mediated photothermal effect of GO resulting from its NIR optical absorption ability.14–17 However, its inefficient photothermal effect becomes the main obstacle for using GO as a drug delivery system or a PA imaging agent, attributing to the structural defects in the regular flat geometry of graphene introduced by oxidative processes. In comparison with the plasmonic photoacoustic contrast agents, such as gold nanorods, nanoshells, nanocages, nanostars, nanotripods and nanovesicles, GO is hardly employed for PA imaging owing to its weak absorption in the NIR region and poor PA conversion efficiency resulting from its smaller sp2 domains than graphene or reduced graphene oxide, greatly hindering its application in cancer theranostics.

Supramolecular chemistry is “chemistry beyond the molecule”, which is based upon intermolecular interactions, i.e. on the association of two or more building blocks being held together by non-covalent interactions.18 Different from traditional molecular chemistry that is predominantly based on the covalent interactions, the reversible and dynamic nature of the non-covalent interactions endows the resultant supramolecular architectures with excellent stimuli-responsiveness and infinite possible applications in various fields.19,20 Bottom-up supramolecular assembly provides a productive tool to fabricate multifunctional hybrid systems by integrating individual functional components through non-covalent interactions. Among various non-covalent interactions, such as π–π stacking, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions and charge-transfer interactions, host–guest molecular recognition is attracting more and more attention from scientists, arising from their distinctive properties by introducing macrocylic hosts into the supramolecular systems.21–28 Considering their highly symmetrical and rigid structures, sophisticated functionalization, and fruitful host–guest chemistry, pillar[n]arenes become star molecules in supramolecular chemistry since 2008.29,30 Compared with other macrocyclic hosts, the easy functionalization and unique symmetrical structure of pillararenes have afforded them superior abilities to bind different guests and provided a useful platform for the fabrication of interesting supramolecular nanomaterials.31–38 Fantastic supramolecular systems, such as liquid crystals, mechanical interlocking molecules, metal–organic frameworks, supramolecular polymers, drug delivery systems, cell imaging agents, transmembrane channels and cell glue, have been constructed by fully taking advantage of their unique properties.39–48 However, the development of functional hybrid materials exploiting the pillar[n]arenes-based platforms is scant until now.

Herein, we report a novel strategy for preparing a supramolecular hybrid material (GO@CP6⊃PyN) fabricated from GO and a pillar[6]arene-based host–guest complex by hierarchical self-assembly, which exhibited near-infrared (NIR) light-triggered PA and ultrasound (US) signal amplification. For this purpose, a CO2-responsive host–guest complex (CP6⊃PyN) is constructed by using a pillar[6]arene CP6 containing 12 tertiary amine groups as the host and an amphiphilic molecule PyN containing a pyrene tail as the guest. Driven by the π–π stacking between GO and the pyrene, and host–guest interactions between CP6 and PyN, CP6⊃PyN is attached on the surface of GO to form the hybrid material. The bicarbonate counterions on the surface of GO@CP6⊃PyN are decomposed into carbon dioxide (CO2) triggered by the NIR light-mediated photothermal effect of GO. In vitro and in vivo investigations demonstrated that the resultant CO2 nanobubbles acting as “molecular boosters” can be used to significantly enhance the PA and US signals.

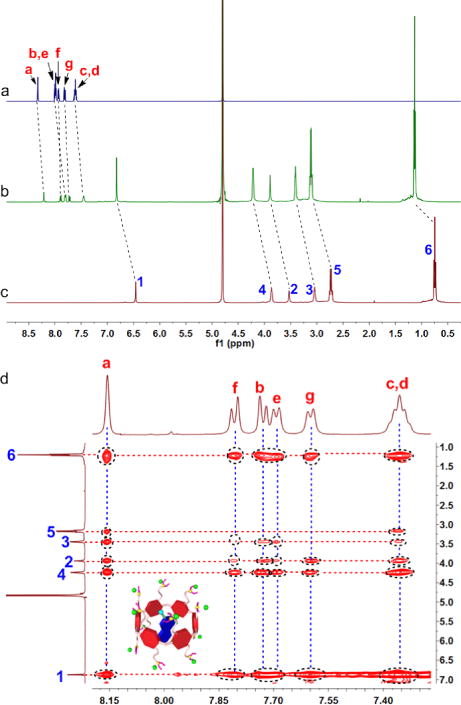

The neutral pillar[6]arene P6 was not able to interact with PyN in water due to its poor solubility and the shortage of driving forces. Host–guest complexation was achieved after the tertiary amine parts were changed into cationic tertiary ammonium groups upon protonation by CO2. Multiple electrostatic interactions were responsible for the formation of the inclusion complex, which was demonstrated by 1H NMR and 2D NOESY spectroscopies. Considering the poor solubility of PyN in water, sodium 2-naphthalenesulfonate (M) was employed as a model compound to study the host–guest complexation. The 1H NMR spectrum of an equimolar solution of CP6 and M in D2O exhibits only one set of peaks, suggesting the complexation was rapidly exchanging on the 1H NMR time scale (Fig. 1b). In comparison with the spectrum of free M (Fig. 1a), significant chemical shift changes were monitored for the resonances related to the protons on M, because these protons were threaded in the cavity and shielded by the electron-rich cyclic structure by the formation of CP6⊃M. Additionally, the peaks corresponding to the protons on CP6 (H1–6) shifted down-field upon formation of host–guest complex, further confirming the interactions between CP6 and M. These observations indicated that the cavity of pillar[6]arene was large enough to wrap the guest molecule. 2D NOESY NMR spectroscopy was utilized to provide convincing insight into the formation of host–guest inclusion complex. As shown in Fig. 1d, strong nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) correlations were detected between the peaks of protons on M (Ha–g) and CP6 (H1–6), demonstrating that the naphthalene ring was penetrated into the cavity of the pillararene moiety, thus forming a 1:1 [2]pseudorotaxane-type host–guest complex.

Fig. 1.

1H NMR spectra (500 MHz, D2O, 295 K) of (a) M (2.00 mM), (b) CP6 (2.00 mM) and M (2.00 mM), and (c) CP6 (2.00 mM). (d) 2D NOESY NMR spectrum (500 MHz, D2O, 295 K) of CP6 (10.0 mM) and M (10.0 mM).

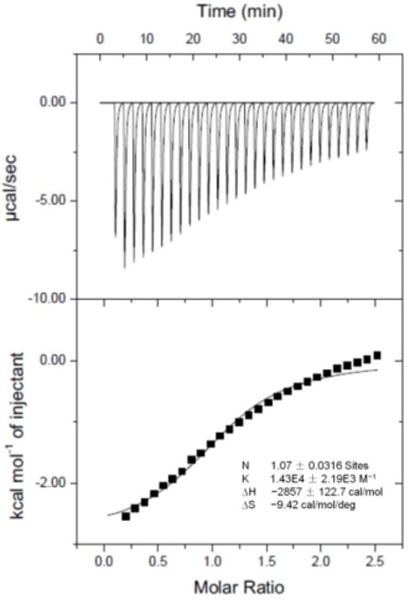

The binding affinity (Ka) of CP6⊃M was measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) investigation, where the Ka value of CP6⊃M was determined to be (1.43 ± 0.22) × 104 M−1 in 1:1 complexation (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, some thermodynamic parameters (enthalpy and entropy changes, ∆H° and ∆S°, respectively) were obtained. As shown in Fig. 2, we knew that this complexation was primarily driven by the enthalpy change with entropic assistance (T∆S>0; ∆H < 0; |∆H| > |T∆S|).

Fig. 2.

Microcalorimetric titration of M with CP6 in water at 298.15 K. Top: raw ITC data for 27 sequential injections (10 μL per injection) of an M solution (2.00 mM) into a CP6 solution (0.100 mM); Bottom: net reaction heat obtained from the integration of the calorimetric traces.

The direct evidences for the formation of CP6⊃PyN were obtained from conductivity test and TEM investigations. The critical aggregation concentration of PyN was measured to be 2.43 × 10−7 M (Fig. S9), and pronouncedly increased to 1.07 × 10−6 M in the presence of CP6 (Fig. S10), ascribing to the host–guest complexation. As shown in TEM images, the nanosheets self-assembled from PyN transformed into nanoparticles by adding CP6 caused by the host–guest interactions (Fig. S11). The reason for the morphology changes of the self-assemblies was that the membrane curvature of the nanosheets became higher upon the insertion of CP6 arising from the generation of electrostatic repulsion and steric hindrance.49

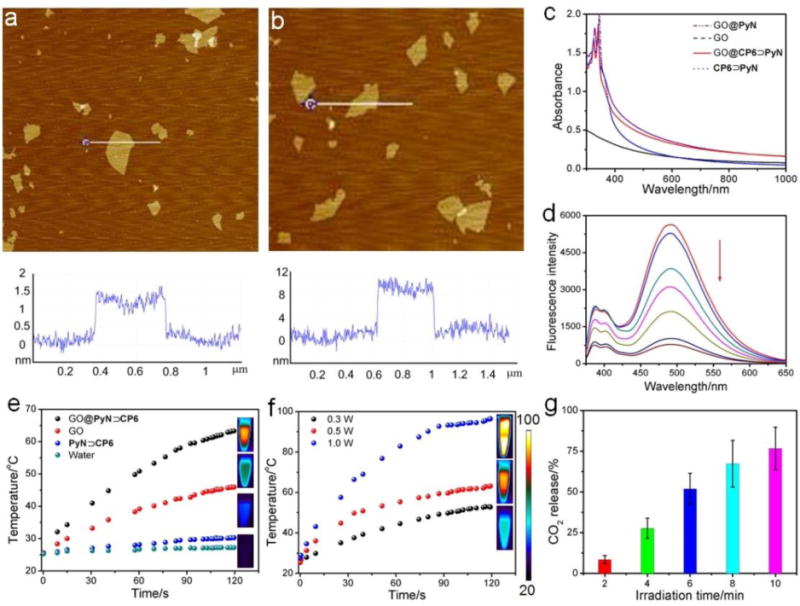

GO@CP6⊃PyN hybrids were prepared by sonication of CP6⊃PyN (500 mg) in H2O (100 mL) with 50 mg of GO for 4 h. After the sonication, the supernatant was dialyzed against H2O to remove excess amount of free CP6⊃PyN from the solution. Notably, the stability of the resultant supramolecular hybrid material was extremely high, the homogeneous solution of GO@CP6⊃PyN could stand for more than 2 months without precipitation (Fig. S17). In order to verify the successful preparation of GO@CP6⊃PyN, various characterizations were carried out, including atomic force microscope (AFM), thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA), UV-vis and fluorescence titrations. AFM image of GO@CP6⊃PyN shown in Fig. 3b indicated that the height of the supramolecular hybrid material was ca. 10.2 nm, apparently thicker than that of pristine GO (1.18 nm, Fig. 3a). According to the molecular model, the length of CP6⊃PyN was calculated to be about 4.1 nm (Fig. S13), approximately equal to half of the thickness changes of GO in the presence and absence of CP6⊃PyN. Driven by the π-π stacking interactions, the hydrophobic section containing the pyrenyl ring attached on the surfaces of GO to form GO@CP6⊃PyN, where the hydrophilic part containing the host–guest complex dispersed in the water. In the UV-vis spectrum of GO@CP6⊃PyN, the characteristic peaks at 325 and 341 nm ascribing to the pyrenyl group were recorded (Fig. 3c), further confirming the π-stacking of CP6⊃PyN to GO. Interestingly, gradual increase in absorption in the range between 500 and 1000 nm was observed upon addition of CP6⊃PyN (Fig. S14). This phenomenon was extremely conducive to improving the photothermal effect and PA signal of the resultant supramolecular hybrid material by increasing its light absorption efficiency. Fluorescence titration experiment was conducted to compare the difference in fluorescence emission between the solution of CP6⊃PyN and GO@CP6⊃PyN. Fig. 3d shows a broad emission band ranging from 425 to 650 nm, characteristic emission of pyrene excimer in aqueous solution. However, gradual addition of GO into the solution led to strong fluorescence quenching. This phenomenon was most likely caused by the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) effect, where CP6⊃PyN acted as a donor fluorophore and GO acted as the acceptor.50,51 By introducing the cationic host–guest complex into the hybrid material, zeta potential value of GO increased from −37.4 to 8.7 mV (Fig. S15). Moreover, the content of CP6⊃PyN in the supramolecular hybrid material was measured by TGA. TGA showed that the weight ratio between GO and CP6⊃PyN was 1:1 (Fig. S16), indicating that the loading content was quite high. These data together strongly support the successful fabrication of GO@CP6⊃PyN.

Fig. 3.

AFM images of (a) GO and (b) GO@CP6⊃PyN. (c) UV-vis spectra of GO, CP6⊃PyN, GO@PyN and GO@CP6⊃PyN. (d) Fluorescence titration spectra of CP6⊃PyN (2 μM) in the presence of increasing GO. (e) The photothermal heating curves of pure water, CP6⊃PyN, GO and GO@CP6⊃PyN (the concentration of GO and CP6⊃PyN was 250 μg/mL) under 808 nm laser irradiation at the power density of 0.5 W/cm2. (f) The photothermal heating curves of GO@CP6⊃PyN under 808 nm laser irradiation at different power density. (g) CO2 release from GO@CP6⊃PyN upon laser irradiation for different time period (808 nm, 0.5 W/cm2).

To evaluate the photothermal properties of GO@CP6⊃PyN, different nanomaterials (GO, CP6⊃PyN, GO@CP6⊃PyN) were dispersed in water and then irradiated with a suitable laser (808 nm, 0.5 W/cm2). The solution temperature was then monitored as a function of time (Fig. 3e). Negligible temperature change was detected for pure water. Upon laser illumination, the temperature of GO@CP6⊃PyN solution increased from 25.4 to 63.3 °C within 3 min, in sharp contrast to the small temperature changes of the irradiated GO (∆T = 20.5 °C) and the CP6⊃PyN (∆T = 4.9 °C) samples. This temperature elevation of the GO@CP6⊃PyN solution was also confirmed by thermal images monitored using an IR camera that showed a red color (GO@CP6⊃PyN) versus a blue color (pure water, Fig. 3e). Compared with that of GO, the temperature changes for GO@CP6⊃PyN were much effective under the same conditions, demonstrating the GO@CP6⊃PyN can rapidly and efficiently convert NIR light into thermal energy. The reason was that the absorbance of GO@CP6⊃PyN increased significantly compared with that of pristine GO (Fig. 3c and Fig. S14), which was favorable to enhance its photothermal conversion efficiency, thus implying that CP6⊃PyN played a significant role in this supramolecular hybrid material. Meanwhile, GO@CP6⊃PyN aqueous solutions at the same concentration was exposed to an 808 nm NIR laser at different power densities from 0.3, 0.5 and 1.0 W/cm2 for 3 min, an obvious laser power-dependent temperature increase was observed (Fig. 3f).

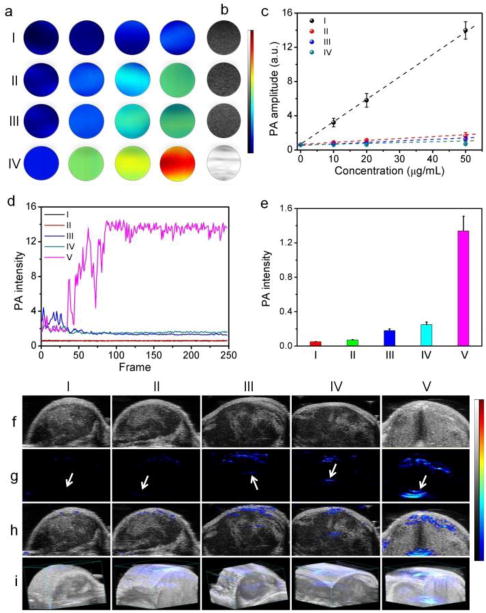

By taking advantage of the NIR light-mediated photothermal effect, GO@CP6⊃PyN can be used as a heat source to trigger the decomposition of the bicarbonate counterions, thus generating CO2 nanobubbles. Therefore, we envisaged that CP6⊃PyN could act as a supramolecular chaperone to enhance the US and PA signals of the hybrid material. In order to monitor the release of CO2, we detected the weight loss of GO@CP6⊃PyN in the presence of NIR light irradiation at 808 nm for different time. During the experiments, we observed that the solution temperature increased to 82 °C after 10 min irradiation. Fig. 3g verified the irradiation-dependent CO2 release, and 76.8% of the bicarbonate counterions were decomposed upon NIR light irradiation for 10 min. The formed nanobubbles were able to reflect and scatter ultrasound effectively (being echogenic), which could be utilized as contrast agents in diagnostic ultrasonography. Fig. 4b exhibited the 2D ultrasound images taken after 20 s of ultrasonication for the tube of water was doped with CP6⊃PyN, GO, GO@WP6⊃PyN and GO@CP6⊃PyN, respectively. Compared with the other samples, considerable echo signals captured in conventional B-mode, were observed for the tube filled with aqueous solution containing GO@CP6⊃PyN. Notably, the US signal arising from GO@WP6⊃PyN was much lower than that of GO@CP6⊃PyN. The only difference between them located in the counter-anions of these hybrid materials, indicating that the generation of CO2 was responsible for US resonation.

Fig. 4.

(a) In vitro PA images, (b) US images, and (c) concentration-dependent PA intensity of (I) CP6⊃PyN, (II) GO, IIII) GO@WP6⊃PyN, and (IV) GO@CP6⊃PyN. (d) PA spectra of (I) PBS, (II) CP6⊃PyN, (III) GO, IV) GO@WP6⊃PyN, and (V) GO@CP6⊃PyN. In vivo (e) PA intensity, (f) 2D US images, (g) PA images, (h) merge images, and (i) 3D PA images of tumor tissues before and after the intratumoral administrations of (I) PBS, (II) CP6⊃PyN, (III) GO, (IV) GO@WP6⊃PyN, and (V) GO@CP6⊃PyN. Arrows indicate the location of injections.

A preliminary evaluation of phantoms containing aqueous solutions of CP6⊃PyN, GO, or GO@WP6⊃PyN showed that they generated weak photoacoustic signal intensities (Fig. 4a). In sharp contrast, the PA signal produced by the sample of GO@CP6⊃PyN was much stronger at the same concentration. The PA signal intensity of GO@CP6⊃PyN was linearly correlated with its concentration (R2 = 0.99). Additionally, the linear slope of GO@CP6⊃PyN was markedly higher than those of the other groups (Fig. 4c), suggesting that GO@CP6⊃PyN can be a promising PA contrast agent. It is intriguing to find that an increase in PA intensity was monitored by a factor of ca. 4 upon NIR laser irradiation (Fig. 4d, Fig. S18–22). This phenomenon was not observed in the previous PA imaging studies. The reason for this PA enhancement might be the generation of CO2 nanobubbles through NIR light-mediated photothermal effect of GO, acting as nanoamplifiers to enhance the PA signal by increasing the vibration of the medium. In our case, GO@CP6⊃PyN possessed stronger photothermal effect, so it is no surprising that the PA signal amplification by GO@CP6⊃PyN is remarkably higher than those of CP6⊃PyN, GO and GO@WP6⊃PyN.

Prior to the bio-relevant applications of GO@CP6⊃PyN, its cytotoxicity was evaluated using a 3-(4′,5′-dimethylthiazol-2′-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. As shown in Fig. S23, the relative cell viability of GO@CP6⊃PyN was higher than 80% even at a high concentration, confirming the excellent biocompatibility of this supramolecular hybrid material. With the proof-of-concept imaging results in hand, in vivo experiments were conducted to verify the US and PA imaging capabilities of GO@CP6⊃PyN using nude mice bearing U87MG tumor via intratumor injection (250 μg/mL, 20 μL). Negligible US contrast enhancement in tumor tissues was detected for the mice treated with GO, CP6⊃PyN or GO@WP6⊃PyN under B-mode (Fig. 4f). On the contrary, the US contrast of the tumor tissue for the mouse injected with GO@CP6⊃PyN was brightened and the gray scale intensity increased effectively. Note that although the tumors were injected sporadically, the ultrasound signal is rather homogeneous throughout the tumor region, firmly demonstrating the excellent tissue permeability of the generated CO2 nanobubbles arising from their small size. Like micrometer-sized counterparts (microbubbles), these nanobubbles effectively reflected ultrasound, which were suitable contrast agents for US imaging. From the PA images (Fig. 4g), we found that the enhancement in PA signal was negligible for the mice injected with GO, CP6⊃PyN or GO@WP6⊃PyN. In sharp comparison with these groups, the PA signal in the region of interest increased significantly for the tumors treated with GO@CP6⊃PyN, which was about 5.36, 7.44, and 18.9 times higher than those observed in the groups treated with GO@WP6⊃PyN, GO, and CP6⊃PyN, respectively (Fig. 4e). Interestingly, the tertiary amine groups on the pillar[6]arene were able to be protonated by bubbling with CO2,38 thus this supramolecular hybrid could be repeatedly used. These preliminary results suggest that our supramolecular hybrid material could be a promising candidate for US and PA imaging contrast enhancement, where the generated CO2 nanobubbles acted as “molecular boosters”.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we developed a novel supramolecular hybrid material GO@CP6⊃PyN integrating GO and a pillar[6]arene-based host–guest complex (CP6⊃PyN) driven by the non-covalent interactions. By employing the NIR light-mediated photothermal effect of GO, the bicarbonate counterions on the surface of the supramolecular hybrid material were decomposed into CO2 nanobubbles upon NIR laser irradiation. The generated CO2 nanobubbles acting as “molecular boosters” can be used to enhance the US and PA signals, resulting from their small size and excellent tissue permeability. On the other hand, the supramolecular formulation effectively increased the NIR absorption of the resultant supramolecular hybrid material, improving the photothermal effect of GO@CP6⊃PyN, which was further beneficial to the enhancement of its PA signal. This supramolecular method provides an exceedingly exquisite strategy to improve the PA and US performances of the functional hybrid materials by fully taking advantage of supramolecular chemistry, which paved a distinctive way to develop smart nanomaterials for imaging-guided theranostic applications.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

(a) Chemical structures of the building blocks (P6, CP6, WP6, PyN and M). (b) Schematic representation of the preparation of supramolecular hybrid material (GO@CP6⊃PyN) exhibiting NIR light-triggered PA and US imaging enhancement.

Conceptual insights.

As an emerging non-invasive diagnostic modality, photoacoustic (PA) imaging integrating the excellent tissue penetration of ultrasound (US) and high sensitivity of optical imaging provides extraordinary opportunities for detecting and monitoring disease pathophysiology in vivo. Superior contrasts with high optical-to-acoustic conversion efficiency are urgently needed for excellent-performance PA imaging, of which the PA agents can effectively convert the absorbed light to localized volume heating, thus resulting in transient thermoelastic expansion and consequently broadband acoustic waves. Unfortunately, thermoelastic expansion that is the least efficient mechanism becomes the main obstacle inhibiting the clinical applications of PA imaging. Herein, we develop a novel supramolecular hybrid material (GO@CP6⊃PyN) fabricated from graphene oxide (GO) and a pillar[6]arene-based host–guest complex (CP6⊃PyN) by hierarchical self-assembly to solve this scientific issue. Carbon dioxide nanobubbles are generated in situ due to the decomposition of bicarbonate counterions triggered by the NIR light-mediated photothermal effect of GO, which can be used as “molecular boosters” to significantly enhance US/PA signal amplitudes through thermoelastic expansion. This supramolecular strategy possessing the ability to change the fate of existing nanomaterials opens new opportunities for the fabrication of new and excellent imaging agents, showing irreplaceable advantages in theranostics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and National Institutes of Health (ZIA EB000073), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21674091, 21434005, 91527301), the National Basic Research Program (2013CB834502), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant LR16E030001), and the Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Supramolecular Structure and Materials.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Author contributions

G. Yu, Z. Mao, F. Huang and X. Chen conceived and designed the research. X. Fu conducted the AFM measurements. J. Yang and L. Shao performed the 1H NMR and 2D NOESY studies. Z. Wang, Y. Liu and Z. Yang carried out the PA imaging. Z. Mao performed TGA studies. G. Yu, F. Zhang, W. Fan, J. Song and Z. Zhou analysed the data. G. Yu, Z. Mao, C. Gao, F. Huang and X. Chen co-wrote the paper.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Notes and references

- 1.Zhang HF, Maslov K, Stoica G, Wang LV. Nat Biotech. 2006;24:848–851. doi: 10.1038/nbt1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pu K, Shuhendler AJ, Jokerst JV, Mei J, Gambhir SS, Bao Z, Rao J. Nat Nanotech. 2014;9:233–239. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H, Zhang P, Smaga LP, Hoffman RA, Chan J. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:15628–15631. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YS, Frey W, Kim S, Kruizinga P, Homan K, Emelianov S. Nano Lett. 2011;11:348–354. doi: 10.1021/nl1042006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi Y, Qin H, Yang S, Xing D. Nano Res. 2016;9:3644–3655. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miao Q, Pu K. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016;27:2808–2823. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang K, Zhang S, Zhang G, Sun X, Lee ST, Liu Z. Nano Lett. 2010;10:3318–3323. doi: 10.1021/nl100996u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Wang J, Ren J, Qu X. Adv Mater. 2013;25:6737–6743. doi: 10.1002/adma.201302810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung C, Kim YK, Shin D, Ryoo SR, Hong BH, Min DH. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:2211–2224. doi: 10.1021/ar300159f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Grüner G, Zhao Y. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1:2542–2567. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20405g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Xia J, Zhao Q, Liu L, Zhang Z. Small. 2010;6:537–544. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson JT, Tabakman SM, Liang Y, Wang H, Casalongue HS, Vinh D, Dai H. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6825–6831. doi: 10.1021/ja2010175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Zhang YM, Chen Y, Zhao D, Chen JT, Liu Y. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:4208–4215. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Lee D, Kim J, Kim T, Kim WJ. ACS Nano. 2013;7:6735–6746. doi: 10.1021/nn403096s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miao W, Shim G, Lee S, Lee S, Choe YS, Oh YK. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3402–3410. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanmugam V, Selvakumar S, Yeh CS. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:6254–6287. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00011k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song J, Yang X, Jacobson O, Lin L, Huang P, Niu G, Ma Q, Chen X. ACS Nano. 2015;9:9199–9209. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fyfe MCT, Stoddart JF. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:393–401. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehn JM. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:151–160. doi: 10.1039/b616752g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Wang C. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:94–101. doi: 10.1039/b919678c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang QC, Qu DH, Ren J, Chen K, Tian H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2661–2665. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeon YJ, Kim H, Jon S, Selvapalam N, Seo DH, Oh I, Park CS, Jung SR, Koh DS, Kim K. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15944–15945. doi: 10.1021/ja044748j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang WH, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:7425–7427. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niu Z, Gibson HW. Chem Rev. 2009;109:6024–6046. doi: 10.1021/cr900002h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang W, Schäfer A, Mohr PC, Schalley CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2309–2320. doi: 10.1021/ja9101369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu K, Vukotic VN, Loeb SJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2168–2172. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo DS, Liu Y. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:5907–5921. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35075k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lan Y, Loh XJ, Geng J, Walsh Z, Scherman OA. Chem Commun. 2012;48:8757–8759. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34016j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogoshi T, Kanai S, Fujinami S, Yamagishi TA, Nakamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5022–5023. doi: 10.1021/ja711260m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogoshi T, Yamagishi T-a, Nakamoto Y. Chem Rev. 2016;116:7937–8002. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui W, Tang H, Xu L, Wang L, Meier H, Cao D. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2017;38:1700161. doi: 10.1002/marc.201700161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song N, Chen DX, Xia MC, Qiu XL, Ma K, Xu B, Tian W, Yang YW. Chem Commun. 2015;51:5526–5529. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08205b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang W, Chen LJ, Wang XQ, Sun B, Li X, Zhang Y, Shi J, Yu Y, Zhang L, Liu M, Yang HB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:5597–5601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500489112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo L, Nie G, Tian D, Deng H, Jiang L, Li H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:12713–12716. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray J, Kim K, Ogoshi T, Yao W, Gibb BC. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:2479–2496. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00095b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng B, Kaifer AE. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:9788–9791. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo M, Wang X, Zhan C, Demay-Drouhard P, Li W, Du K, Olson MA, Zuilhof H, Sue ACH. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:74–77. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jie K, Zhou Y, Yao Y, Shi B, Huang F. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:10472–10475. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao DR, Kou YH, Liang JQ, Chen ZZ, Wang LY, Meier H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9721–9723. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strutt NL, Forgan RS, Spruell JM, Botros YY, Stoddart JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5668–5671. doi: 10.1021/ja111418j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Si W, Chen L, Hu XB, Tang G, Chen Z, Hou JL, Li ZT. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:12564–12568. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duan Q, Cao Y, Li Y, Hu X, Xiao T, Lin C, Pan Y, Wang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10542–1054. doi: 10.1021/ja405014r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Han K, Li J, Jia X, Li C. Polym Chem. 2013;4:3998–4003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H, Ma X, Nguyen KT, Zhao Y. ACS Nano. 2013;7:7853–7863. doi: 10.1021/nn402777x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan LL, Li H, Tao Y, Zhang SXA, Wang B, Yang YW. Adv Mater. 2014;26:7027–7031. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun Y, Guo F, Zuo L, Hua J, Diao G. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12042. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu G, Yung BC, Zhou Z, Mao Z, Chen X. ACS Nano. 2018;12:7–12. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b07851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang R, Sun Y, Zhang F, Song M, Tian D, Li H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:5294–5298. doi: 10.1002/anie.201702175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu G, Zhou X, Zhang Z, Han C, Mao Z, Gao C, Huang F. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:19489–19497. doi: 10.1021/ja3099905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu G, Xue M, Zhang Z, Li J, Han C, Huang F. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:13248–13251. doi: 10.1021/ja306399f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang HL, Wei XL, Zang Y, Cao JY, Liu S, He XP, Chen Q, Long YT, Li J, Chen GR, Chen K. Adv Mater. 2013;25:4097–4101. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.