Abstract

Infective endocarditis (IE) secondary to Staphylococcus lugdunensis has been increasingly recognized since 1988. IE-related thromboembolism represents an associated complication of the disease and carries a dismal prognosis. However, the incidence of cerebrovascular accident secondary to S. lugdunensis IE is relatively uncommon and its treatment has not been clearly elucidated yet.

We performed an extensive literature search using Pubmed, Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar to identify the articles using the following keywords: ‘Staphylococcus lugdunensis’, ‘infective endocarditis’, ‘stroke’, and ‘cerebrovascular accident.’ Patient characteristics, risk factors, severity of neurological deficit, echocardiographic findings, medical management, required surgical intervention, complications and mortality rate were reviewed in detail.

Eighteen cases (mean age of 47.8 years, 55% male) from 17 publications with S. lugdunensis-related cerebrovascular accident (CVA) were identified. Of these, 16 (87%) cases were left-sided endocarditis and 10 (61%) cases experienced right-sided neurological deficit. The source of infection was documented in eight cases (50%) in which four cases (50%) were related to groin-related procedures and the mitral valve (52.5%) was mostly infected followed by aortic valve (37%). Surgical valve replacement was done in 61% of patients and overall mortality rate was 22%.

S. lugdunensis endocarditis is associated with high mortality and morbidity, including a higher prevalence of CVA. Early disease identification with aggressive intervention is crucial for better outcomes.

Keywords: staphylococcus lugdunensis, endocarditis, cerebrovascular accident, cardiology, infectious endocarditis

Introduction and background

Infective endocarditis (IE) has long been recognized and treated over three centuries starting from 1674 when Lazare Riviere first noticed IE as a disease [1]. The overall annual incidence of IE varies from 3 to 7 per 100,000 person-years in the global population study while Bor et al. reported that approximately 40,000 IE cases/year with a 14.5% mortality rate occurred in the USA [2,3]. IE can be caused by various pathogens including bacteria and fungus although the former is more common. Due to frequent invasive procedures such as cardiac catheterization, defibrillator and central line placement, Staphylococcus aureus has become the most causal organism followed by Streptococcus species with an estimated incidence of 49.3% and 24.7%, respectively [2].

Coagulase-negative Staphylococci (CoNS) is known to be a nonpathogenic commensal in individuals with normal immune response. However, this concept changed when Staphylococcus lugdunensis, a member of the CoNS group, was first identified as a causal pathogen of IE in 1988 by Freney et al. [4]. Although most CoNS tend to have more latent pathogenicity, S. lugdunensis is an exception with a higher degree of virulence similar to Staphylococcus aureus. S. lugdunensis often requires immediate and aggressive treatment including surgical intervention. Embolic complications related to IE represent a more severe endpoint of the disease including S. lugdunensis endocarditis-induced embolic stroke. The question regarding how and when to start treatment remains unclear as no definitive management plan is described in the guidelines.

This review article aims to evaluate the clinical presentation, characteristics and risk factors, as well as the necessity of surgical treatment in cerebrovascular accident (CVA) due to S. lugdunensis endocarditis.

Review

Materials and methods

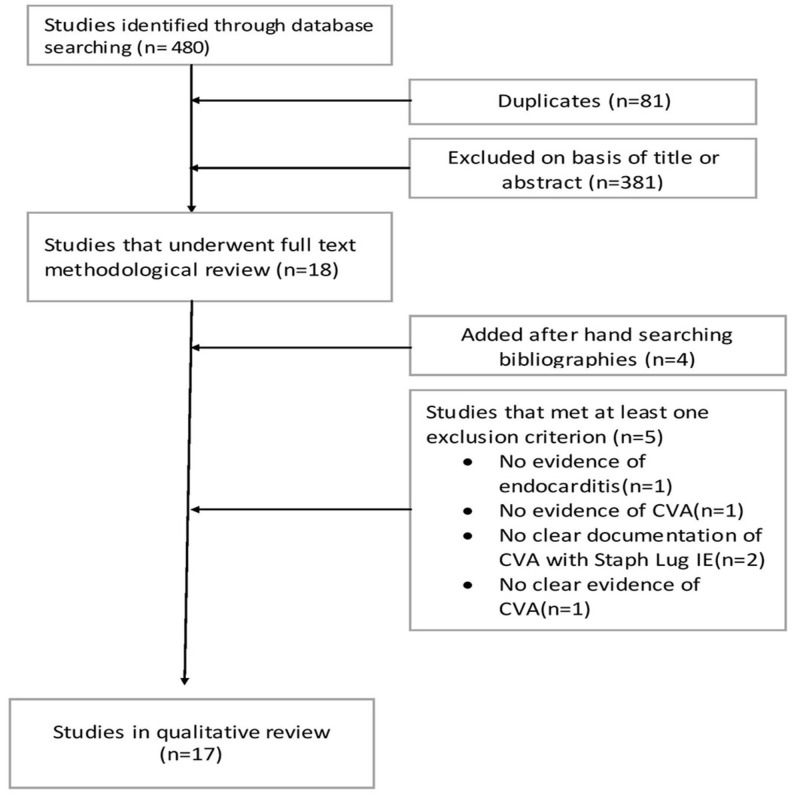

We performed an extensive literature search using Pubmed, Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar to identify peer-reviewed original research, review articles, case reports and series using ‘Staphylococcus lugdunensis’, ‘infective endocarditis’, ‘stroke’, and ‘cerebrovascular accident’. The search period included all the articles published until January 2017. Search result yielded mostly case reports and case series. Patient characteristics, risk factors, echocardiographic findings, vegetation size, required surgical intervention and its complications, and mortality rate were reviewed in detail (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Literature search and selection.

CVA: Cerebrovascular accident.

Results

A total of 17 original published articles were considered appropriate for inclusion in our review article (Figure 1). Out of these 17 studies, 16 were case reports from Italy [5,6], Switzerland [7], USA [8-11], UK [12,13], Morocco [14], Taiwan [15,16], Saudi Arabia [17], Spain [18,19], and Norway [20] while one case series was from Greece [21]. Koh et al. had reported the first case of S. lugdunensis endocarditis-associated CVA from London, UK in 1996 [12]. A total of 18 cases from 17 articles were included in the review article. All cases are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and demographic information.

IE: Infective endocarditis; IV: Intravenous; TTE: Trans-thoracic echocardiogram; URI: Upper respiratory tract infection; LV: Left ventricle; PPM: Permanent pacemaker.

| First author (year) [Ref. No.] | Total patients | Age (Years) | Sex (M/F) | IV Drug abuse history | Previous IE history | Portal of entry | Location of IE | Type of valve | Vegetation TTE (Y/N) |

| Htoo Kyaw (2016) [11] | 1 | 63 | 1/0 | Not-mentioned | None | Unknown | Mitral valve | Native mitral valve | Y |

| Hossein Schandiz (2015) [20] | 1 | 56 | 1/0 | Not-mentioned | None | Vasectomy | Mitral valve | Native mitral valve | N (autopsy finding) |

| Manova David (2015) [10] | 1 | 36 | 1/0 | Not-mentioned | None | Vasectomy | Mitral valve | Native mitral valve | Y |

| Jose Kuzhively (2014) [9] | 1 | 61 | 1/0 | Polysubstance abuse | None | Spinal fracture fixation | Mitral valve anterior leaflet | Native mitral valve | Y |

| Wei-Chi Tsai (2013) [15] | 1 | 48 | 1/0 | Not-mentioned | None | Femoral catheterization | Aortic valve | Native aortic valve | Y |

| Federico Pacei (2013) [6] | 1 | 77 | 1/0 | Not-mentioned | None | Mechanical valve replacement for AS and CABG | Mechanical aortic valve | Mechanical aortic valve | Y |

| Rosaria Pecoraro (2012) [5] | 1 | 18 | 0/1 | Not-mentioned | None | Not-mentioned | Anterior mitral valve leaflets | Native mitral valve | Y |

| Kalliopi-Stavroula Chatzigeorgiou (2010) [21] | 2 | 67.5 | 0/2 | Not-mentioned | None | Not-mentioned | LV outflow/PPM lead with Tricuspid valve | Prostatic aortic valve / native tricuspid valve with PPM | Y |

| Asmaa Tamdy (2010) [14] | 1 | 17 | 0/1 | Not-mentioned | None | Not-mentioned | Mitral valve | Native mitral valve | Y |

| Yeun Tarl Fresner Ng Jao (2010) [16] | 1 | 44 | 1/0 | Not-mentioned | None | Pneumonia | Mitral and aortic valve | Native mitral and aortic valve | Y |

| Khaled E. Alebrahim (2007) [17] | 1 | 13 | 1/0 | Not-mentioned | None | Not-mentioned | Mitral valve | Native mitral valve | Y |

| S. Gianella (2006) [7] | 1 | 49 | 0/1 | Not-mentioned | None | Not-mentioned | Bicuspid aortic valve | Native bicuspid aortic valve | Y |

| M Rodríguez-Gascón (2003) [18] | 1 | 77 | 0/1 | Not-mentioned | None | Valvular surgery/URI | Mitral valve | Native mitral valve | Y |

| A. Sánchez (2000) [19] | 1 | 71 | 0/1 | Not-mentioned | None | Not-mentioned | Aortic valve | Native aortic valve | Y |

| Susan J. Burgert (1999) [8] | 1 | 33 | 1/0 | Not-mentioned | None | Not-mentioned | Bicuspid aortic valve | Native bicuspid aortic valve | Y |

| T. W. Koh (1996) [12] | 1 | 52 | 0/1 | Not-mentioned | None | Not-mentioned | Mitral valve | Native mitral valve | Y |

| B Walsh and JP Mounsey (1990) [13] | 1 | 32 | 1/0 | Not-mentioned | None | Vasectomy | Aortic valve | Native aortic valve | N |

Table 2. Summary of infective endocarditis treatment and outcome.

CVA: Cerebrovascular accident; LVOT: Left ventricular outflow tract; PPM: Permanent pacemaker.

| First author (year) [Ref. No.] | Vegetation size on echocardiography | CVA severity | Medical treatment (Y/N) | Penicillin resistance (Y/N) | Surgical intervention (Y/N) | Required valve replacement | Outcome |

| Htoo Kyaw (2016) [11] | Vegetation on anterior and posterior mitral valve leaflets | Aphasia and right-sided hemiplegia | Y | N | Y | Y | Recovered |

| Hossein Schandiz (2015)[20] | Massive vegetation on mitral valve | Not mentioned: presented as syncope | N | Y | N (planned) | N | Died before surgery |

| Manova David (2015) [10] | 7 mm on anterior leaflets and 15 mm on posterior leaflet of mitral valve | Dysarthria and left-sided hemiparesis | Y | N | Y | Y | Recovered |

| Jose Kuzhively (2014) [9] | 15.5 x 11.1 mm on the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve | Right hemiplegia and facial palsy | Y | N | N | N | Recovered |

| Wei-Chi Tsai (2013) [15] | Aortic valve vegetation with perivalvular abscess | Right internuclear ophthalmoplegia | Y | N | N (planned) | N | Died before surgery |

| Federico Pacei (2013) [6] | Not mentioned | Quadriplegia | Y | N | N | N | Recovered |

| Rosaria Pecoraro (2012) [5] | 10.3 x 16.6 mm on anterior mitral valve leaflet | Right leg weakness | Y | N | Y | Y | Recovered |

| Kalliopi-Stavroula Chatzigeorgiou (2010)[21] | 18 x 22 mm at LVOT/7 x 16 mm on PPM leads and small vegetation on tricuspid valve | Dysarthria and facial nerve paresis | Y/Y | N/N | Y/N (only removal of PPM wires) | N/N | Recovered (died 5 years later with calciphylaxis)/Recovered |

| Asmaa Tamdy (2010)[14] | 17 x 5 mm on the anterior mitral valve with small vegetation on both leaflets of mitral valve | Right hemiplegia and aphasia | Y | N | N (planned) | N (planned) | Died before surgery |

| Yeun Tarl Fresner Ng Jao (2010) [16] | Not mentioned | Right hemiparesis | Y | N | Y | Y | Died |

| Khaled E. Alebrahim (2007) [17] | 7 x 8 mm on anterior and 3 x 6 mm posterior leaflets of mitral valve | Right hemiparesis and aphasia | Y | N | Y | Y | Recovered |

| S. Gianella (2006) [7] | 12 x 4 mm on the bicuspid aortic valve | Right hemiparesis and aphasia | Y | N | Y | Y | Recovered |

| M Rodríguez-Gascón (2003) [18] | 3 x 3 cm vegetation on mitral valve | Left hemiparesis | Y | N | N | N | Recovered |

| A. Sánchez (2000) [19] | Not mentioned | Generalized weakness | Y | N | Y | Y | Recovered |

| Susan J. Burgert (1999) [8] | 5 mm perforation with multiple vegetations on aortic valve | Dysarthria, aphasia and right hemiparesis | Y | N | Y | Y | Recovered |

| T. W. Koh (1996) [12] | Vegetation on posterior leaflets of the mitral valve | Dysphasia and right facial weakness | Y | N | Y | Y | Recovered |

| B Walsh and JP Mounsey ( 1990) [13] | Not mentioned | Right-hand weakness | Y | N | Y | Y | Recovered |

Demographics

Most of the reported cases were from European countries and only two cases were from China. Four reported cases were from the USA and very limited published data regarding S. lugdunensis endocarditis-induced CVA has been noted in the past literature. Of these 18 cases, 10 were men and eight were women with mean age of 47.9 years (range 13-77 years).

Risk factors, patients’ characteristics and clinical spectrum

The risk factors associated with Staphylococcus lugdunensis are intravenous drug abuse, previous history of infective endocarditis, and surgical intervention in the groin area. Among patients with a documented source of infection, four cases (50%) were noted to have either vasectomy or femoral catheterization. No previous history of IE was reported in any of the cases.

Left-sided IE is the most common site involved, accounting for 94.7% of all total cases in which mitral valve, aortic valve, or both amounted to 52.5%, 37%, and 5.2%, respectively (Table 3). Foreign body-related IE comprised three cases including one case with pacemaker-related endocarditis and two cases of prosthetic valve IE. Sixteen individuals (88.88%) were found to have vegetations on echocardiogram with the largest measuring 3 cm x 3 cm in diameter on the mitral valve. The neurological deficit was mostly located in the right side (61%) with facial palsy in 17% and left-sided hemiparesis in 11% (Table 2).

Table 3. Characteristic, location of infected valves, and outcome of Staphylococcus lugdunensis infective endocarditis.

LVOT: Left ventricular outflow tract.

| Total cases, N (%) | |

| Type of infected valve | |

| Mitral valve, aortic valve, tricuspid valve, pulmonary valve, LVOT | 10 (52.5%), 7 (37%), 1 (5.2%), 01 (5.2%) |

| Location of vegetation | |

| Left sided, right sided | 17 (94.4%), 1 (5.5%) |

| Valve replacement | |

| Yes, No | 11 (61.1%), 7 (39%) |

| Outcome | |

| Recovered, died | 14 (78%), 4 (22%) |

Investigation, medical and surgical treatment

Blood culture remains the gold standard to diagnose this type of bacteria and it should be in the differential whenever coagulase-negative Staphylococcus growth is present. Once S. lugdunensis is isolated, early antibiotic therapy and surgical intervention should be considered.

Antibiotic sensitivity testing showed methicillin susceptibility in most of the cases except one case (5.5%) which had penicillin resistance and was consistent with the previous reported literature. In studies by Anguera et al. and Hellbacher et al., S. lugdunensis was susceptible to penicillin with a rate of 84% and 85%, respectively [22,23]. Most of the cases were treated with sensitivity-guided medical therapy but 12 cases (66.6%) were eventually required to undergo surgical treatment. This particular finding is relatively higher than other pathogens including S. aureus.

Anguera et al. had reported a four-year study of IE in which surgical intervention was performed in Staphylococcus aureus IE (~37%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (~60%), and Staphylococcus lugdunensis (~70%) [22]. Another national study done by Ferreiros et al. and Krcmery et al. showed that surgical treatment with valve replacement was done in 26-42% of IE caused by all pathogens [24,25]. Despite S. lugdunensis IE-related CVA being mostly methicillin/penicillin sensitive, it is less likely to be eradicated by medical therapy alone and often requires surgical intervention.

Perhaps extrapolating from our experience in treating CVA associated with S. Lugdunensis IE, early surgical treatment was often required to have a better outcome. However, the latest 2015 AHA guideline has failed to mention any specific recommendation for this disease entity [26]. Thus, clinicians will have to make a decision based on their clinical experiences which could create a heterogeneity in disease management.

Prognosis

Unlike other organisms, S. lugdunensis is characterized by an insidious clinical course resulting in a higher mortality. The mortality rate was 22% (four out of 18 cases) but only one case out of 11 cases that underwent surgical intervention expired compared to those with medical treatment (8.3% vs 37.5%) (Table 3).

Anguera et al. disclosed that the changes in mortality rate before and after 1995 were primarily due to earlier recognition of S. lugdunensis with more aggressive management including surgical intervention [22]. According to the two studies done in 1993 and 2003, the mortality rate was 16% due to CoNS IE as well as 22.4% with S. aureus IE, which had a reduced mortality rate than our review [27,28]. In a 2010 review article done by Liu et al., among 68 patients with S. lugdunensis infective endocarditis, the mortality rate was 38.8% [29]. Although there are no randomized controlled clinical trials given the disease rarity; based on the above data and past experiences, we can at least extrapolate that early surgical intervention would be a reasonable approach especially in those with CVA related to S. lugdunensis IE.

Conclusions

Compared to other organisms, S. lugdunensis seems to display a higher propensity to cause CVA in our review. In addition, embolic stroke secondary to S. lugdunensis IE appears to have a higher incidence in middle age men than women. Invasive procedures such as catheterization and vasectomy should be performed with proper sterile protocol to help reduce S. lugdunensis bacteremia or endocarditis. Although broad-spectrum antibiotics are typically the first medical treatment option, some patients may require a valve replacement surgery suggesting a higher virulence compared to other CoNS organism. The efficacy of medical therapy alone compared to the possible superiority of early surgical approach needs further investigation. However, it is challenging to conduct future large-scale studies to clarify the exact timeline of the surgical approach as S. lugdunensis endocarditis-related embolic stroke is a rare disease.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Historical aspects of infective endocarditis (Article in English, Portuguese) Grinberg M, Solimene MC. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2011;57:228–233. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302011000200023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Infective endocarditis in the US, 1998-2009: a nationwide study. Bor DH, Woolhandler S, Nardin R, Brusch J, Himmelstein DU. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:60033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temporal trends in infective endocarditis in the context of prophylaxis guideline modifications: three successive population-based surveys. Duval X, Delahaye F, Alla F, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1968–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staphylococcus lugdunensis sp. nov. and Staphylococcus schleiferi sp. nov., two species from human clinical specimens. Freney J, Brun Y, Bes M, et al. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1988;38:168–172. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis complicated by embolism in an 18-year-old woman with mitral valve prolapse. Pecoraro R, Tuttolomondo A, Parrinello G, Pinto A, Licata G. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2013;2013:730924. doi: 10.1155/2013/730924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinal epidural abscess as a complication of cardiosurgery. Pacei F, Bet L. Neurol Sci. 2014;35:805–807. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1670-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conservative management of a brain abscess in a patient with Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis. Gianella S, Ulrich S, Huttner B, Speich R. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:476–478. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Destructive native valve endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Burgert SJ, LaRocco MT, Wilansky S. http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/10456723. South Med J. 1999;92:812–814. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199908000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The long CoN (S): a case of Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis with cerebral and coronary embolism. Kuzhively J, Patel SA, Abraham H. J Med Cases. 2014;5:535–537. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Embolic stroke caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis complicating vasectomy in a 36-year-old man. David M, Loftsgaarden M, Chukwudelunzu F. Tex Heart Inst J. 2015;42:585–587. doi: 10.14503/THIJ-14-4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Septic embolic stroke resulting from Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis. Kyaw H, Shaikh AZ, Yaratha G, Misra D. http://www.ochsnerjournal.org/doi/pdf/10.1043/TOJ-16-0028?code=occl-site. Ochsner J. 2017;17:184–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Successful treatment of Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis complicated by multiple emboli: a case report and review of the literature. Koh TW, Brecker SJ, Layton CA. Int J Cardiol. 1996;55:193–197. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(96)02679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staphylococcus lugdunensis and endocarditis. Walsh B, Mounsey JP. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC502305/ J Clin Pathol. 1990;43:171–173. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.2.171-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Multiple mycotic aneurysms reveal Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis in a young patient. Tamdy A, El Louali F, Ounzar M, et al. Heart Lung. 2011;40:352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.One-and-a-half syndrome: a less appreciated emergency in native valve infective endocarditis. Tsai W-C, Chen W-L, Tsao Y-T. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:459. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis. Jao YTFN, Fang C-C, Wang S-P. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6d92/f6bb79e67f871812048b8bae38ab81d3e926.pdf Acta Cardiol Sin. 2010;26:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Successful surgical treatment of mitral valve endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Alebrahim K. JKAU: Med Sci. 2007;14:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acute Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis with septic cerebral and pulmonary emboli, showing favorable evolution (Article in Spanish) Rodriguez-Gascon M, Roig P, Montagud JB, Merino J. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2003;21:465–467. doi: 10.1016/s0213-005x(03)72987-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aggressive acute endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis complicated with multiple cerebral septic emboli (Article in Spanish) Sanchez A, Martinez I, Sanz F, Lopez F, Aguado JM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11198008. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2000;18:526–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis following vasectomy-report of a case history and review of the literature. Schandiz H, Hermansen NO, Jørgensen T, Roald B. APMIS. 2015;123:726–729. doi: 10.1111/apm.12396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Two successfully treated cases of Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis. Chatzigeorgiou K-S, Ikonomopoulou C, Kalogeropoulou S, et al. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;68:445–448. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staphylococcus lugdunensis infective endocarditis: description of 10 cases and analysis of native valve, prosthetic valve, and pacemaker lead endocarditis clinical profiles. Anguera I, Del Rio A, Miro JM, et al. http://heart.bmj.com/content/91/2/e10. Heart. 2005;91:0. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.040659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staphylococcus lugdunensis: clinical spectrum, antibiotic susceptibility, and phenotypic and genotypic patterns of 39 isolates. Hellbacher C, Törnqvist E, Söderquist B. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:43–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Etiology and risk factors of 339 cases of infective endocarditis: report from a 10-year national prospective survey in the Slovak Republic. Krcmery V, Gogova M, Ondrusova A, et al. J Chemother. 2003;15:579–583. doi: 10.1179/joc.2003.15.6.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epidemiologic, clinical, and microbiologic profile of infective endocarditis in Argentina: a national survey. The Endocarditis Infecciosa en la República Argentina-2 (EIRA-2) Study. Ferreiros E, Nacinovich F, Casabé JH, et al. Am Heart J. 2006;151:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Circulation. 2015;132:1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Endocarditis due to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Microbiologic, epidemiologic, and clinical considerations. Whitener C, Caputo GM, Weitekamp MR, Karchmer AW. http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/8463655. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1993;7:81–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and endocarditis. Petti CA, Fowler VG Jr. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12874895. Cardiol Clin. 2003;21:219–233. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staphylococcus lugdunensis infective endocarditis: a literature review and analysis of risk factors. Liu P-Y, Huang Y-F, Tang C-W, et al. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43:478–484. doi: 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]