Abstract

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs) are a result of the teratogenic effects of alcohol on the developing fetus. Decades of research examining both individuals with FASDs and animal models of developmental alcohol exposure have revealed the devastating effects of alcohol on brain structure, function, behavior, and cognition. Neurotrophic factors have an important role in guiding normal brain development and cellular plasticity in the adult brain. This chapter reviews the current literature showing that alcohol exposure during the developmental period impacts neurotrophin production and proposes avenues through which alcohol exposure and neurotrophin action might interact. These areas of overlap include formation of long-term potentiation, oxidative stress processes, neuroinflammation, apoptosis and cell loss, hippocampal adult neurogenesis, dendritic morphology and spine density, vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, and behaviors related to spatial memory, anxiety, and depression. Finally, we discuss how neurotrophins have the potential to act in a compensatory manner as neuroprotective molecules that can combat the deleterious effects of in utero alcohol exposure.

1. INTRODUCTION

Neurotrophins, members of one of the three families of neurotrophic factors, play a key role in proper brain development and are important mediators of synaptic plasticity involved in memory formation during adulthood. Disruption of neurotrophins or receptor function during development could result in long-term changes to cognition, memory formation, and mood. Prenatal alcohol exposure has long been known to cause severe cognitive and behavioral deficits due to functional and anatomical changes within the brain. The deficits caused by alcohol exposure in utero are collectively known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs), which manifest with a variety of physical, intellectual, social, and executive functioning impairments. Recent evidence suggests that alcohol–neurotrophin interactions during development could contribute to the damaging effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on neuroplasticity, learning, and memory measures. Specifically, disruption of neurotrophin signaling and prenatal alcohol exposure not only results in overlapping detrimental effects, but there is also emerging evidence that alcohol may act directly on neurotrophin pathways. In this chapter, we review the role of neurotrophins during brain development, how prenatal alcohol exposure affects brain function and structure through the life span, and potential ways in which alcohol and neurotrophins interact to result in alcohol-related deficits.

2. NEUROTROPHINS AND THE DEVELOPING BRAIN

The proper timing of the birth, survival, and death of neurons is carefully orchestrated with the help of neurotrophin signaling. Each neurotrophin exhibits a unique expression profile throughout development in the brain and periphery, with alterations to expression causing significant and long-term consequences on cell structure and function. Studies in chicken embryos show neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) as the earliest neurotrophin found in the developing embryo, with expression of its receptor, tropomyosin receptor kinase C (TrkC), beginning in the neural plate (Bernd, 2008). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its receptor, TrkB, emerge later, appearing first in the neural tube. Nerve growth factor (NGF) and its receptor, TrkA, is first expressed in peripheral sensory neurons later in embryonic development, suggesting a role for this neurotrophin in later developmental stages rather than initial cell proliferation and migration processes. Another set of neurotrophins, vascular endothelial growth factors or VEGF, is critical for embryonic vasculogenesis. VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and VEGF-B have three receptors, VEGFR1–3, with VEGF-A and its receptor VEGFR2 being the most plentiful in the brain. Exposure to toxins or stress during gastrulation and neurulation could influence expression of these neurotrophins in a timing-dependent manner.

Neurotrophins also show overlapping but distinctive patterns of expression during later brain development. In rat embryos, levels of NT-3, NGF, and BDNF increase to coincide with mass neurogenesis in the developing central and peripheral nervous system around embryonic days (E) 11–12 (Maisonpierre et al., 1990). During these first waves of neurogenesis, NT-3 is the most abundantly produced neurotrophin, with BDNF being far less plentiful, suggesting a prominent role of NT-3 during initial neurogenesis. In addition to being developmentally regulated, neurotrophic expression is also brain region specific, with expression of NT-3, NGF, and BDNF decreasing in concentration in the adult vs prenatal spinal cord; conversely, expression of NGF and BDNF increases into adulthood in the hippocampus (Karege, Schwald, & Cisse, 2002; Katoh-Semba, Semba, Takeuchi, & Kato, 1998; Timmusk et al., 1993), while expression of NT-3 peaks in the early postnatal period (equivalent to third trimester of human pregnancy). Based on these expression profiles, NT-3 might play a more important role in early neuronal proliferation and migration, with NGF and BDNF contributing to later developmental processes, such as neuronal survival, neurite outgrowth, and synaptic plasticity.

3. ALCOHOL AS A TERATOGENIC AGENT

During prenatal development, the fetus could be exposed to a variety of environmental or infectious agents, called teratogens, which impact normal growth and survival, ultimately resulting in malformations to the fetus or “birth defects.” Common teratogens include pesticides, infections, drugs of abuse, and prescription medication. Teratogens exert their deleterious effects through a variety of pathways and the resulting defects can range from severe (limb loss following maternal use of thalidomide) to subtle (delayed language skills following prenatal cocaine exposure). One of the most widely used teratogenic agents is alcohol, which will be the focus of this chapter.

Alcohol (ethyl alcohol or ethanol, specifically) is a commonly used psychoactive drug with sedative properties. Primarily used recreationally, over 70% of adults over age 18 report using alcohol in the past year (NIAAA, 2015). Binge drinking (usually defined as >4 drinks in one sitting) is also prevalent, with over 24% of adults reporting at least one episode of binge drinking in the past month. Alcohol exerts its sedative effects through inhibition of NMDA-subtype glutamate receptor activity and enhancement of chloride ion flow through GABAA receptor ion channels. In adults, even low doses of alcohol can result in impaired motor control, judgment, and reaction time due to the widespread and potent effects of alcohol on multiple brain regions.

Pregnant women also report relatively high rates of alcohol consumption, with 20–30% of women reporting some degree of alcohol use during their pregnancy, despite well-publicized campaigns to warn women of potential danger to the developing fetus. When a pregnant woman ingests alcohol, the alcohol easily passes through the placenta, meaning that blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) in the fetus are comparable to or even higher than those recorded from the mother (Nava-Ocampo, Velazquez-Armenta, Brien, & Koren, 2004; van Faassen & Niemelä, 2011). While alcohol is easily metabolized in adults through the action of alcohol dehydrogenase in the stomach and liver; however, fetuses lack the enzymes necessary for the breakdown of alcohol. Thus, the alcohol is only metabolized after being circulated back into the maternal blood supply, meaning that concentrations of alcohol within the placenta could be higher than the mother’s BAC and remain elevated for a prolonged period.

3.1 Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

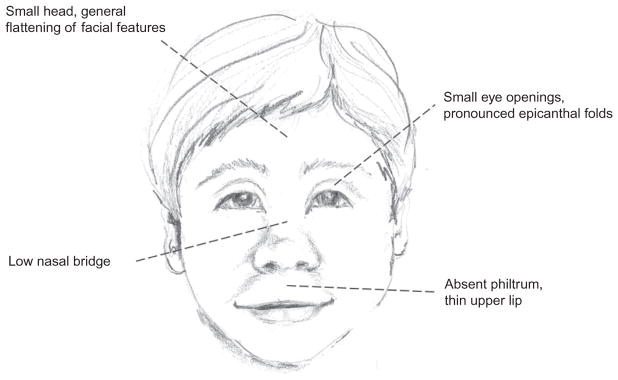

Fetal exposure to alcohol can cause a wide range of long-lasting physiological and behavioral effects, collectively referred to as FASDs. The most severe form of fetal alcohol effects is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which manifests with craniofacial malformations (Fig. 1), including short palpebral fissure length, smooth philtrum, and a thin upper lip, reduced body and brain weight, intellectual disabilities, and cognitive and behavioral impairments. Prevalence statistics for the United States have been historically difficult to obtain due to the stigma associated with maternal drinking, making pregnant women less likely to accurately report rates of alcohol consumption. The current statistics estimate that up to 5% of live births each year in the Unites States are affected by FASD, while FAS occurs in approximately 0.1% of live births (Centers for Disease Control, 2015; May et al., 2009). Children with FASD, including FAS, can require lifelong care, both in terms of extra medical expenditures in childhood (Amendah, Grosse, & Bertrand, 2011) and access to specialized services to help cope with learning disabilities and other behavioral needs. Estimates from 2002 indicated that care for children with FAS costs on average $2 million across the life span, and that services for these individuals cost the United States approximately $4 billion a year (1998 estimate; Lupton, Burd, & Harwood, 2004). More recent estimates or costs including the full range of FASD are not readily available, but it can be inferred that care for these individuals is a significant use of resources, both for families and society as a whole.

Fig. 1.

Classic craniofacial dysmorphologies associated with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). All illustrations drawn by P.T. Boschen.

Cost estimates for individuals with FAS and the full spectrum of FASDs are difficult to calculate due to the range of primary and secondary disabilities caused by prenatal alcohol exposure. Primary disabilities in children with FASDs refer to changes to the brain that directly result in impaired mental function, such as decreased volume of both white and gray matter structures which cause deficient performance on reading, writing, and arithmetic tasks (Mattson, Riley, Delis, Stern, & Jones, 1996; Mattson, Riley, Sowell, et al., 1996). These children often perform poorly on working memory and IQ tests (Mattson, Goodman, Caine, Delis, & Riley, 1999; Mattson, Riley, Gramling, Delis, & Jones, 1997; Rasmussen, Soleimani, & Pei, 2011) and are more likely to require special education services. These disabilities often extend beyond scholastic performance and can affect social interactions, executive functioning, impulse control, and emotion regulation, often resulting in higher rates of incarceration and mental illness in adulthood (Franklin, Deitz, Jirikowic, & Astley, 2008; Irner, Teasdale, & Olofsson, 2012; Kodituwakku, Handmaker, Cutler, Weathersby, & Handmaker, 1995; Pei, Job, Kully-Martens, & Rasmussen, 2011; Stevens et al., 2012; Streissguth et al., 2004).

Public safety campaigns, including announcements from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the CDC in 2015 and 2016 officially recommending no alcohol use during pregnancy, have ultimately not eradicated the existence of a completely preventable cause of mental retardation, leading researchers to continue to investigate (1) the molecular, cellular, and system-wide damage caused by prenatal alcohol exposure; and (2) potential behavioral and pharmacological interventions to reverse the detrimental cognitive and behavioral effects. This pursuit has led to a vast number of animal models of FASDs which have been critical in understanding how the dose, timing, and pattern of alcohol exposure can impact behavioral and neuroanatomical outcomes.

3.2 Modeling Developmental Alcohol Effects in Experimental Animals

Rats and mice are the most commonly used for FASD models, though sheep and primates are sometimes used as well. Rat and mouse pups are born at a developmentally earlier stage than humans, meaning that brain development occurring during the third trimester of human pregnancy takes place over the first 2 postnatal weeks in rodents (Dobbing & Sands, 1979). Alcohol exposure during specific points in development results in damage to whatever developmental process is occurring during this time. For example, administration of alcohol during the first trimester equivalent (gastrulation or neurulation) would cause craniofacial dysmorphologies analogous to those seen in children with FAS, but administration during the third trimester equivalent would produce neuroanatomical damage to late-developing brain structures such as the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, or cerebellum. As mentioned earlier, neurotrophins also display developmentally regulated expression patterns, suggesting that interactions between alcohol and neurotrophin function would likely depend on developmental stage.

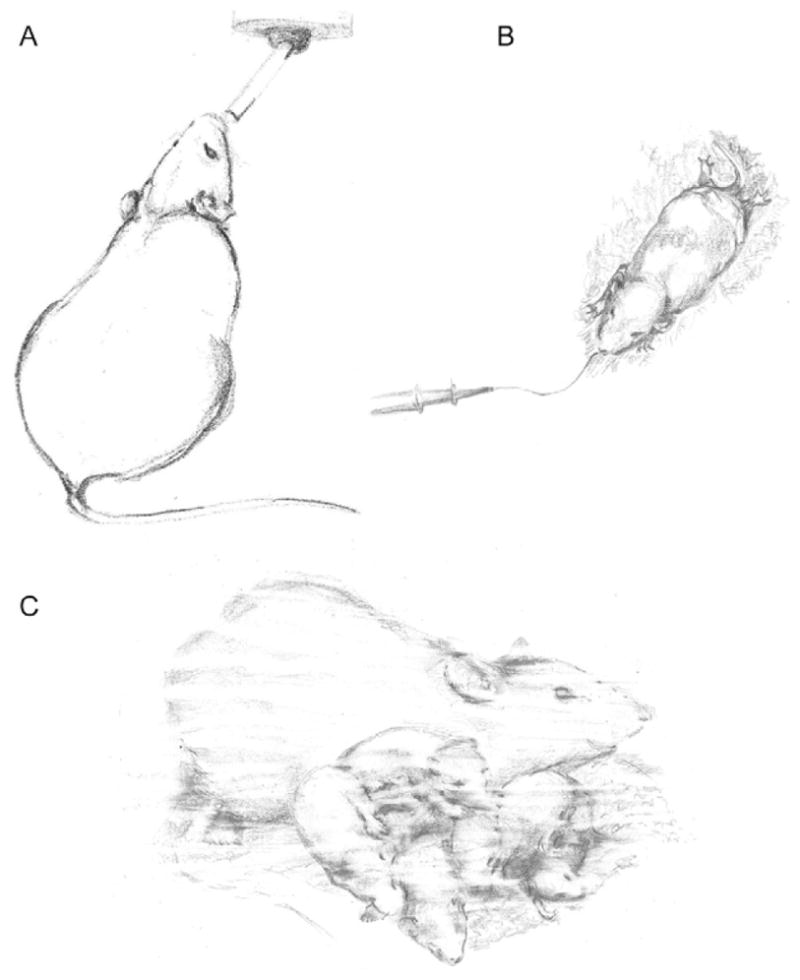

FASD models can be split into two broad categories: prenatal and postnatal exposure. Prenatal models mimic alcohol exposure during approximately the first two trimesters of human pregnancy, while postnatal models mimic exposure during the third trimester. In prenatal models, alcohol is administered to the dam either through maternal voluntary drinking (Fig. 2A), intraperitoneal or subcutaneous injection or intragastric gavage. Voluntary drinking paradigms are relatively low stress for the dam; however, they usually model low-to-moderate levels of drinking due to the amount of alcohol being ingested are under the control of the dam rather than the experimenter directly. In contrast, injections and gavage are able to achieve higher BACs and the relative amount of alcohol administered is constant across animals; however, injections and gavage are inherently stressful procedures. Postnatal models deliver the alcohol directly to the pups, enabling control and alcohol-exposed pups to be assigned to the same litter, which leaves maternal care of the pups unaffected. Intragastric intubation (Fig. 2B) and injections are commonly used methods of alcohol delivery for neonatal pups, achieving high BACs in a controlled dose, with the negative consequence of increased stress and morbidity rate. Vapor inhalation paradigms (Fig. 2C) are also commonly used, with pups being placed in a chamber filled with ethanol vapor for 1–4 h at a time. Long periods of maternal separation can be detrimental to pup development, so dams are often placed in the vapor chamber with the pups. As a result, this method usually models low-to-moderate levels of alcohol exposure in order to leave the dam unimpaired and able to sufficiently care for the pups. While ethanol vapor can cause irritation to mucous membranes, the stress induced by this method is minimal.

Fig. 2.

Representative illustration of alcohol exposure paradigms. (A) Maternal drinking during pregnancy, (B) postnatal gavage/intragastric intubation, and (C) postnatal exposure using a vapor chamber (dam with pups).

Two important differences distinguish the models described earlier: developmental time point (trimester equivalent) and level of BAC achieved. These two variables can determine the type and severity of alcohol-induced damage depending on what developmental processes are occurring. For instance, alcohol exposure during gastrulation can affect neural tube closure, while alcohol exposure during the third trimester equivalent could impact synaptogenesis and cell differentiation in the prefrontal cortex. These developmental windows also have unique expression patterns of neurotrophins, meaning that alcohol would have differing interactions with neurotrophins based on exposure time point and level of alcohol administered. In the remainder of the chapter, we will discuss how rodent models of FASD target neurotrophin expression during different developmental periods, and other avenues through which alcohol and neurotrophins may interact, from molecules to behavior. Finally, we will discuss cases in which neurotrophins may act in a neuroprotective capacity following developmental alcohol exposure.

4. NEUROTROPHINS AS TARGETS OF ALCOHOL EXPOSURE

Alcohol during development can have direct consequences on neurotrophin signaling, even long after cessation of the exposure. The effects of alcohol exposure on neurotrophin and receptor expression are highly dependent on a number of variables, including the alcohol dose and developmental window targeted, timing of the tissue collection following the exposure, route of administration, and the brain region in question. Inter-study variability on these factors can make the literature difficult to parse. The most well-studied neurotrophin–alcohol relationship is the interaction with BDNF and its receptor TrkB, though numerous papers have assessed NGF as well. NT-3 and VEGF have been less explored, though it is likely that more resources will be put toward investigating VEGF in more detail in the future due to an emerging understanding of its role in neuroplasticity.

4.1 BDNF

In recent years, numerous studies have been published trying to determine how developmental alcohol exposure affects BDNF levels in the brain, and often these studies have been at odds with one another due to the range of alcohol exposure paradigms, rodent species, and timing of the tissue analysis utilized, as well as differences in which brain regions were examined. While there is little doubt rodent models of FASDs do impact BDNF, questions remain regarding the directionality and stability of the changes. It is not known if alcohol interacts with the BDNF molecule or TrkB receptor directly; it seems more likely that BDNF levels are affected through action of alcohol on NMDA or GABAA receptors. For example, in cerebellar granule cell cultures, BDNF was increased following NMDA treatment; however, this enhancement was blocked following pretreatment with ethanol (Bhave, Ghoda, & Hoffman, 1999).

Models of prenatal alcohol exposure have consistently demonstrated changes to BDNF signaling in various brain regions. Following exposure from gestational days 5–20, BDNF protein and mRNA were reduced in the rat cortex and hippocampus when assessed on PD7-8 (Feng, Yan, & Yan, 2005). Mice exposed to alcohol prenatally show decreased levels of BDNF protein, total and exon III-, IV-, and VI-driven Bdnf mRNA transcripts in adulthood in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; Caldwell et al., 2008); at 18 months of age, levels of BDNF were depleted in the liver and elevated in the hippocampus of prenatally exposed mice, suggesting an interaction with developmental alcohol exposure and natural aging processes (Ceccanti et al., 2012). Prenatal exposure also has been shown to alter levels of the TrkB receptor, inhibiting the phosphorylation of TrkB on PD7-8 while leaving the total amount of TrkB unchanged (Feng et al., 2005). In another study, male rat pups exposed to alcohol in utero also showed decreased levels of TrkB receptors on postnatal day 1 in the hippocampus, no changes to TrkB in the septum or cerebellum, and increased levels in cortex (Moore, Madorsky, Paiva, & Barrow Heaton, 2004). Interestingly, female pups showed a different pattern of changes, with levels of TrkB decreased in septum, no changes in hippocampus, and consistent increases in TrkB in cortex. Most alterations to receptor number had returned to baseline by postnatal day 10. These studies highlight the variety of changes to BDNF signaling which can vary by brain region, sex of animal, and time point. In general, the consensus of these prenatal studies seems to point to decreased BDNF production in hippocampus following prenatal alcohol exposure, with more variability reported in other brain regions.

BDNF and TrkB receptor expression have also been shown to be altered in postnatal alcohol exposure models. Studies assessing BDNF 24 h or less following neonatal exposure have found increased protein levels in hippocampus and cortex (PD2-10 or PD4; Heaton, Mitchell, Paiva, & Walker, 2000; Heaton et al., 2003), increased BDNF and TrkB protein, Bdnf total and exon I- and IV-driven gene expression in hippocampus (PD4-9; Boschen, Criss, Palamarchouk, Roth, & Klintsova, 2015), and decreased Bdnf and Trkb gene expression in cerebellum (PD2-3 and PD4 exposures; Heaton et al., 2003; Light, Ge, & Belcher, 2001). Another report assessing Bdnf mRNA and downstream signaling pathways on PD8 following PD5-8 alcohol exposure found decreased levels of Bdnf and downregulation of the MAPK and Akt pathways in the cerebral cortex (Fattori, Abe, Kobayashi, Costa, & Tsuji, 2008). Postnatal exposure (PD10-15) via vapor inhalation disrupted normal age-related fluctuations in Bdnf gene expression, with alcohol-exposed rats having higher expression in the hippocampus on PD16 and 20 and decreased expression on PD60 compared to control animals, again supporting an interaction between alcohol exposure and age on alterations in neurotrophin signaling (Miki et al., 2008). Aside from age-related fluctuations, BDNF production is also linked to the circadian cycle. Allen, West, Chen, and Earnest (2004) reported that PD4-9 alcohol exposure significantly decreased overall levels of BDNF protein in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and blunted the circadian rhythmicity of expression when the animals were 5–6 months of age. BDNF is thought to contribute to circadian regulation through action in the SCN (Liang, Allen, & Earnest, 2000) and disruptions to circadian rhythms have been reported in both children with FASDs and in rodent neonatal exposure models (Chen, Olson, Picciano, Starr, & Owens, 2012; Sakata-Haga et al., 2006).

4.2 Other Neurotrophic Factors: NGF, NT-3, VEGF

The interaction between alcohol and NGF has been well studied with alcohol addiction models in adult rodents, with levels of NGF often increasing during or immediately following alcohol intake and decreasing during alcohol withdrawal periods (Aloe, Bracci-Laudiero, & Tirassa, 1993; Gericke, Schulte-Herbruggen, Arendt, & Hellweg, 2006; Heberlein et al., 2008). In developmental models, prenatal exposure significantly increased levels of NGF in a cortex/striatum homogenate on PD1, though levels returned to baseline by PD10 (Heaton et al., 2000). Levels of the NGF receptor TrkA were decreased in the male hippocampus and cerebellum and increased in the cortex of male and female pups on PD1 after prenatal exposure (Moore et al., 2004). TrkA levels were also increased in the thymus and spleen of prenatally exposed neonatal mice, possibly contributing to alcohol-related immunodeficiency (Gauthier, 2015; Gottesfeld, Morgan, & Perez-Polo, 1990). Following PD4-10 exposure, NGF protein was upregulated in cortex/striatum on PD10 and remained elevated at PD21, returning to baseline levels by PD60 (Heaton et al., 2000). However, NGF gene expression was unchanged in cerebral cortex on PD8 following PD5-8 alcohol exposure in another study (Fattori et al., 2008), possibly due to differences in route of administration (vapor vs intubation) or specific brain region included in the analyses (cortex/striatum vs cerebral cortex only). The interaction between NGF and withdrawal during the developmental period remains to be elucidated, but work with chronic alcohol administration models in adulthood suggests that there may be a strong relationship that could further propagate tissue damage, making this avenue of research worthy of further investigation.

Limited work has examined how models of FASD impact production on NT-3, and work that has been done has found few alcohol-induced changes. Heaton et al. (2000) found no significant alterations to NT-3 in any brain region following prenatal or postnatal alcohol exposure, and similar findings were reported following PD5-8 exposure (Fattori et al., 2008). Prenatal alcohol exposure did affect levels of the TrkC receptor protein (Moore et al., 2004). TrkC was decreased in the male and female hippocampus and male cerebellum and increased in the male cortex on PD1. On PD10, there were no significant differences for either sex. These results are consistent with the idea that NT-3 plays a large role in early embryonic development and is less critical during the later stages, such as the time points assessed in these studies.

Recent work investigating VEGF has found some evidence that developmental alcohol exposure alters VEGF regulation, which could in turn impact angiogenesis, microvasculature structure, and cell proliferation. Prenatal alcohol exposure decreased VEGF levels in the neonatal mouse cortex on PD2 and induced retraction and reorganization of cortical microvasculature in humans with FAS or partial FAS (Jegou et al., 2012). Age might interact with alcohol’s effects on VEGF, as neonatal alcohol exposure significantly upregulated VEGF levels in the adult mouse hippocampus and cortex (Ceccanti et al., 2012). Since VEGF has a role in both angiogenesis and cytogenesis, enhanced levels of this protein could be a double-edged sword with potential beneficial effects on adult neurogenesis and maintenance of the neurogenic niche, but also possible negative health-related consequences such as increased tumor risk.

5. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN DEVELOPMENTAL ALCOHOL EXPOSURE AND NEUROTROPHINS IN THE BRAIN: MOLECULAR AND INTRACELLULAR EFFECTS

Beyond the direct interaction of developmental alcohol exposure and neurotrophins, there are numerous molecular processes within and between cells affected by both in utero alcohol exposure and neurotrophic factors. This section will discuss how alcohol and neurotrophin signaling either influence or are influenced by NMDA and GABAA receptors, including long-term potentiation (LTP). Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation are two other areas of possible overlap, with both of these processes representing potential sources of secondary tissue damage following developmental alcohol exposure.

5.1 Glutamatergic NMDA Receptors and GABA Receptors

Alcohol acts as a glutamatergic NMDA receptor antagonist and GABAA receptor agonist. These receptor types are also affected by neurotrophins and present a potential area of crossover between neurotrophic factor and alcohol action. Both NMDA and GABA receptors have widespread distribution throughout the brain and are found on most, but not all, neurons. Since glutamate and GABA are the predominant excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters, respectively, alterations to their signaling pathways can impact not only immediate cell and system function but also long-term structural and functional plasticity. Importantly, NMDA receptors are necessary for induction and maintenance of LTP, a critical process for learning and memory formation.

While neurotrophins do not act directly on glutamate receptors, NMDA- and non-NMDA-mediated glutamatergic activity can enhance synthesis of BDNF and NGF in the rodent hippocampus (Lindholm, Castren, Berzaghi, Blochl, & Thoenen, 1994; Zafra, Hengerer, Leibrock, Thoenen, & Lindholm, 1990). NT-3 seems to be unaffected by NMDA receptor activity. The interaction between NMDA receptors and neurotrophins is important as increased activity in a neural system could induce neurotrophic factor synthesis and release to supplement other plasticity-related processes. Activity-dependent BDNF release caused through NMDA receptors can regulate antiapoptotic signaling cascades through the TrkB receptor; blockade of this receptor disrupts the antiapoptotic effect (Bhave et al., 1999). Neurotrophic factors, namely BDNF, have also been shown to be necessary for protein synthesis-dependent, late-phase LTP in the neonatal and adult rodent brain. Even in the presence of protein synthesis inhibitors, administration of BDNF can maintain LTP in vitro (Lu & Chow, 1999) and inhibition of BDNF through antagonists or BDNF scavengers can eliminate previously stable LTP. In the neonatal rat, high-frequency stimulation often only produces short-term potentiation due to synaptic fatigue; however, administration of BDNF allows for induction of LTP in the neonatal brain (Gottschalk, Pozzo-Miller, Figurov, & Lu, 1998). Some authors have posited that it is no coincidence that levels of BDNF increase in the neonatal brain alongside the ability to maintain LTP (Figurov, Pozzo-Miller, Olafsson, Wang, & Lu, 1996). One way in which BDNF is thought to enhance maintenance of LTP is by increasing vesicle docking and neurotransmitter release from the presynaptic terminal (as opposed to direction interaction with AMPA or NMDA receptors). Mutant BDNF knockout mice display fewer docked vesicles and decreased levels of vesicle-docking proteins synaptophysin and synaptobrevin (Pozzo-Miller et al., 1999) and treatment with BDNF attenuates these effects. Increases in region-specific due to BDNF have functional significance, resulting in increased frequency of AMPA-mediated spikes which are connected to vesicle, and thus neurotransmitter, release (Tyler & Pozzo-Miller, 2001). Aside from BDNF, there is evidence that other neurotrophic factors could affect LTP. Recent work has shown that VEGF may play a role in LTP and memory formation, as overexpression of VEGF in vivo enhanced LTP but blockade of VEGF reduced LTP to normal levels (Licht et al., 2011). These data suggest importance of VEGF for enhancement of LTP but not necessarily induction and maintenance of “normal” LTP. The mechanisms through which VEGF affects LTP remain to be determined.

Alcohol is known to act as an NMDA receptor antagonist by reducing ion channel opening probability and open time. Though the precise nature of its antagonistic properties is still unclear, a direct interaction of alcohol with the NMDA receptor is likely due to the rapid reduction in channel activity (<100 ms) (Ron & Wang, 2009). NMDA receptors help regulate neuronal migration and differentiation in the developing brain, making disruption of NMDA receptor activity due to alcohol exposure all the more devastating during this time period (Komuro & Rakic, 1993). A short-term blockade of NMDA receptors in the late fetal or early neonatal period results in widespread apoptosis with a pattern of damage mimicking developmental alcohol exposure (Ikonomidou et al., 1999; Thomas, Fleming, & Riley, 2001). NMDA receptors are also hypothesized to be particularly sensitive to damage through excitotoxic stimulation during the neonatal period (Ikonomidou, Mosinger, Salles, Labruyere, & Olney, 1989), though it is not known if this hypersensitivity could extend to antagonism via alcohol exposure. Rodent models of FASD have also demonstrated that alcohol exposure affects LTP formation in the developing rat hippocampus, though this effect seems to be dose and timing dependent. Administration of alcohol during the third trimester equivalent disrupts LTP in neonatal CA1 in vivo, and in vitro models show that this effect is likely due to action on both the NMDA and AMPA receptor ion channels (Puglia & Valenzuela, 2010a, 2010b). Age of the animal during LTP recording also likely makes a difference, as measurements of LTP in the adult rat brain following prenatal alcohol exposure tell a relatively different story, one that is highly dependent on sex of the animal. While male rats show reduced LTP in adulthood, female animals either exhibit no effect of alcohol exposure or an enhancement of LTP (Sickmann et al., 2014; Titterness & Christie, 2012). This observation in females seems to be independent of circulating estradiol (estrogen), as ovariectomized female rats present with the same pattern; some of the authors suggest increased synthesis of glutamate in females as a potential explanation.

Neurotrophins, such as BDNF, can alter GABAA receptor distribution and reduce inhibitory postsynaptic currents. Administration of BDNF in culture rapidly downregulates postsynaptic inhibitory current which is GABAA receptor mediated; this reduction is due to the presence of fewer postsynaptic GABAA receptors (Brunig, Penschuck, Berninger, Benson, & Fritschy, 2001). BDNF also attracts more glutamatergic terminals to the postsynaptic cell, while at the same time reducing the number of GABAergic terminals, shifting the balance from inhibitory to excitatory (Singh et al., 2006). On the other side of the coin, GABAergic activity can downregulate BDNF and NGF synthesis (Berninger et al., 1995; Lindholm et al., 1994). Interestingly, it has been suggested that GABA signaling during embryonic development, a window during which GABA acts as an excitatory rather than an inhibitory neurotransmitter, might actually enhance BDNF synthesis; the switch to downregulation of BDNF by GABA would arise after GABA changes to an inhibitory role (Zucca & Valenzuela, 2010).

Alcohol binds directly to the GABAA receptor and mimics the effects of GABA by opening the ion channel which allows hyperpolarizing chloride to enter the cell. GABAA agonists, including alcohol, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates, induce apoptosis throughout the developing brain, compounding the cell death related to NMDA receptor antagonism following alcohol exposure. GABAA hyperactivation seems to have the opposite effect during development as it does in the adult brain, where activation of this receptor acts as a protective mechanism against NMDA-related excitotoxic apoptosis (Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Olney et al., 1991, Olney, Wozniak, Jevtovic-Todorovic, & Ikonomidou, 2001). Thus, the fetus is far more sensitive to exposure to GABAmimetic agents compared to adults and alcohol presents a source of cell death on two fronts that work in concert. Normal neuronal maturation relies on a synchrony of signaling pathways, including GABA, glutamate, and neurotrophic factors, to achieve proper cell differentiation, neurite outgrowth, and synaptic integration. GABA is particularly important during development prior to formation of glutamatergic synapses and has an excitatory effect in maturing cells; administration of alcohol to cultured neonatal hippocampal pyramidal cells disrupts GABA-mediated LTP in these cells (Zucca & Valenzuela, 2010).

5.2 Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress damages cells and DNA through the production of peroxidases and other free radical molecules, leading to increased cell death. Neurotrophins have been shown to combat oxidative damage in various disease models through upregulation of antioxidant molecules. Alternatively, reactive oxygen species (ROS) inhibit neurotrophins (Gardiner, Barton, Overall, & Marc, 2009). Diets high in saturated fat increase oxidative stress-related damage and reduce BDNF. Vitamin E supplementation decreased tissue damage and upregulated BDNF, possibly through phosphorylation of synapsin I and activation of CREB signaling pathways (Wu, Ying, & Gomez-Pinilla, 2004). NGF has also been shown to reduce oxidative damage to synaptic transporters by β-amyloid and iron molecules (Guo & Mattson, 2000). Postmortem analysis of brain tissue from autistic donors found increased levels of the ROS 3-nitrotyrosine in the frontal cortex and cerebellum; levels of NT-3 were also found to be increased in some of the same regions; however, more work is needed to determine any type of causation in this association. Cultured hybrid cells made from mitochondrial DNA of Parkinson’s disease patients had enhanced vulnerability to oxidative damage and reduce glutathione presence; however, administration of either BDNF or glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor protected the cells from oxidative stress-induced death (Onyango, Tuttle, & Bennett, 2005). Finally, most relevant to the current topic, BDNF, NGF, and NT-5 all showed neuroprotective effects on oxidative damage in the neonatal brain (Kirschner et al., 1996). Administration of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) into the PD8 striatum caused significant hypoxic lesions to the tissue which were reduced in volume by systemic administration of neurotrophic factors prior to MPP+ injection. While the exact mechanisms of the neurotrophin–oxidative stress interaction are still unclear, it has been proposed that a positive feedback loop between neurotrophin and antioxidant production exists in the healthy brain (Gardiner et al., 2009).

Developmental alcohol exposure has been repeatedly demonstrated to increase markers of oxidative stress in the neonatal and adult rodent brain. Prenatal exposure increased levels of ROS and apoptosis in fetal rat cortical neurons, while antioxidant pretreatment of the cells prevented the apoptosis, meaning ROS production directly contributed to increased alcohol-induced cell death (Ramachandran et al., 2003). Increased levels of the oxidative stress marker lipid peroxidase were found in cultured PC12 (dopaminergic) neurons following acute alcohol administration (Sun, Chen, James-Kracke, Wixom, & Cheng, 1997). Lipid peroxidase was also upregulated throughout the brain for up to 12 weeks following postnatal alcohol exposure (Petkov, Stoianovski, Petkov, & Vyglenova, 1992) and until at least PD60 following perinatal exposure (Brocardo et al., 2012). Perinatal alcohol also increased protein oxidation in the hippocampus and cerebellum and increased anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors in the mice. Animals exposed to aerobic exercise during adolescence had increased levels of the antioxidant glutathione and ameliorated aberrant behavioral performance; however, it is not known if these two results were through overlapping or unique exercise-induced mechanisms.

5.3 Neuroinflammation

Microglial colonization of the CNS occurs during the embryonic stages in rodents, with phenotypically mature microglia comprising the majority of these immune cells by PD14 (Bilbo & Schwarz, 2009). Dysregulation of the developing immune system has the capacity to shape long-term microglial morphological and chemical activation patterns to immune challenges, possibly contributing to the emergence of neurological and psychological disorders in adulthood, including schizophrenia and depression. Immune activation is often modeled through systemic injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), molecules which comprise part of the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria, or the bacteria Escherichia coli. While LPS does not pass the blood–brain barrier, it can still induce a microglial response and upregulation of cytokine production. Immune activation through either of these methods has been shown to reduce levels of neurotrophins in various brain regions, possibly through a negative feedback loop with the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (Calabrese et al., 2014). Injection of LPS significantly decreased BDNF and NGF in the rat hippocampus and throughout the cortex, though the reductions were region specific (Guan & Fang, 2006). NT-3 was only decreased in frontal cortex, suggesting a differential vulnerability of neurotrophin response to infection. Further study found decreased levels of both pro- and mature BDNF isoforms at synapses in the mouse brain, which corresponded with reductions in Bdnf gene expression (Schnydrig et al., 2007). Chapman et al. (2012) demonstrated that E. coli affects CA1 and DG Bdnf gene expression in an exon-specific pattern, with exon I-, II-, and IV-driven transcripts showing the largest reduction. A direct interaction between the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β and BDNF was reported over two decades ago; systemic injection of IL-1β decreased hippocampal Bdnf expression, though the exact mechanism of this interaction is still unclear (Lapchak, Araujo, & Hefti, 1993). Further studies are needed to clarify exactly how infection or cytokines impede neurotrophin production, the exact role of the HPA axis in this process, and whether the findings discussed here also hold true in the developing brain.

Children with in utero exposure to alcohol have a higher risk of developing secondary health complications, such as respiratory illnesses, in part due to increased likelihood of premature birth and nutritional deficiencies in alcohol-exposed infants (Gauthier, 2015). Recent work in animal models has begun to delve into the complex neuroinflammatory response induced by developmental alcohol exposure and investigation of this response as a secondary source of damage during alcohol exposure and withdrawal. To date, most in vivo work has focused on postnatal FASD models and the short-term impact of alcohol on markers of neuroinflammation. PD4-9 exposure in rat and mouse intragastric intubation models increases microglial activation and proinflammatory cytokine gene expression (IL-1β, TNF-α, CCL2, CCL4, CD11b) in the hippocampus (Boschen, Ruggiero, & Klintsova, 2016), cerebellum, and cortex on PD10 (Drew, Johnson, Douglas, Phelan, & Kane, 2015). PD3-5 alcohol vapor inhalation also induced proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in the hippocampus and cerebellum of the neonatal pups, with particular upregulation of cytokine expression during withdrawal periods (Topper, Baculis, & Valenzuela, 2015). Ethanol administration to cultured cerebellar microglia has potentially neurotoxic effects, reducing the number of microglia while simultaneously increasing activation and production of proinflammatory cytokines in the remaining cells (Kane et al., 2011). Tiwari and Chopra (2011) showed that aberrant activation of the developing immune system can have long-term consequences on cytokine expression. PD7-9 alcohol exposure via intubation resulted in enhanced levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus in adulthood. This finding is important as aberrant activation of the immune system early in development could result in overactivation of microglia and overproduction of inflammatory molecules following further immune challenges later in life and contribute to pathological conditions (Bilbo & Schwarz, 2009); overexpression of cytokines at baseline conditions in the alcohol-exposed brain could indicate disruption of normal immune function in these animals. Interestingly, there is limited evidence that postnatal alcohol exposure might also enhance levels of cytokines with antiinflammatory properties. Levels of TGF-β mRNA were increased in the hippocampus on PD10 following PD4-9 alcohol exposure (Boschen et al., 2016) and in the adult cortex and hippocampus following PD7-9 exposure (Tiwari & Chopra, 2011). However, Topper et al. (2015) reported no changes to TGF-β or another antiinflammatory cytokine, IL-10, in the neonatal brain following PD3-5 vapor inhalation; these differences could be due to the model or timing of exposure used. Further investigation of how antiinflammatory cytokines might react to alcohol-induced damage in the developing brain is needed and considered as a potential therapeutic intervention to mitigate apoptosis.

6. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN DEVELOPMENTAL ALCOHOL EXPOSURE AND NEUROTROPHINS: NEUROANATOMICAL AND BEHAVIORAL EFFECTS

6.1 Neuroanatomical Effects

Through action on the molecular mechanisms discussed earlier, alcohol exposure during development exerts deleterious effects on neuroanatomical measures including cell number, dendritic morphology and spine density, the process of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus, and structure of microvasculature. All of these measures can speak to the general health of the neural circuit and give information about potential dysfunction leading to impaired behavioral outcomes. Section 6.1.1 primarily focuses on alcohol’s detrimental effects on brain region volume and cell number. The importance of neurotrophins for cell proliferation and migration cannot be overstated and will be addressed in more detail in the section discussing adult neurogenesis (Section 6.1.2), in addition to evidence that developmental alcohol exposure disrupts these processes. The health of neurons can also be assessed through other means, including the complexity and morphology of the dendritic trees and spine density on the dendrites (Section 6.1.3). Section 6.1.4 reviews how neurotrophins and alcohol impact angiogenesis and microvasculature.

6.1.1 Brain Region Volume and Alcohol-Induced Apoptosis

With the emergence of noninvasive technologies to study brain structure and function in humans, brain region volume, and cortical thickness became a few neuroanatomical measures well characterized in children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Significant reductions in overall brain volumes and in specific brain regions in children with FASDs were reported in several studies (Archibald et al., 2001; Autti-Ramo et al., 2002; Gautam et al., 2015; Johnson, Swayze, Sato, & Andreasen, 1996; Sowell et al., 2002; Willoughby, Sheard, Nash, & Rovet, 2008). Cortical thickness, white matter, and subcortical gray matter in children with prenatal alcohol exposure are also subjects of change; however, the changes in these parameters are not unidirectional: greater cortical thickness was observed in parietal and posterior temporal regions (Fernandez-Jaen et al., 2011; Sowell et al., 2008, 2001, 2002; Yang et al., 2012). In contrast, reduced cortical thickness was reported by other groups (Treit et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2011), especially at ages when cortical thickness is expected to be at its maximum (Robertson et al., 2016). Other brain areas such as the hippocampus (Willoughby et al., 2008), caudate nucleus (Archibald et al., 2001; Cortese et al., 2006; Fryer et al., 2012), and cerebellar vermis (Autti-Ramo et al., 2002; Fryer et al., 2012) had decreased volume, suggesting significant regional loss of cells and neuropil. In addition, results from studies using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) demonstrate that individuals exposed to alcohol in utero have less organized white matter fiber tracts (Wozniak & Muetzel, 2011) and significantly decreased fractional anisotropy in white matter regions (Fryer et al., 2012; Sowell et al., 2008) compared to control subjects. Decreases in overall and region-specific brain volume are well documented in animal models of FASDs (Bonthius & West, 1988, 1990; Maier, Chen, & West, 1996; Maier, Miller, Blackwell, & West, 1999; Napper & West, 1995). More recently, both ex vivo MRI and DTI studies confirmed that animal models of FASDs cause decreased overall brain and cortical volume (Leigland, Budde, Cornea, & Kroenke, 2013; Leigland, Ford, Lerch, & Kroenke, 2013; O’Leary-Moore et al., 2010; Parnell, Holloway, Baker, Styner, & Sulik, 2014; Parnell et al., 2013), as well as abnormally high cerebral cortical functional anisotropy that indicates reduced morphological complexity (Leigland, Budde, et al., 2013; Leigland, Ford, et al., 2013).

One mechanism through which alcohol alters neurodevelopment is by inducing apoptosis, or programmed cell death (Creeley & Olney, 2013; Kerr, Wyllie, & Currie, 1972). A critical process in normal development, apoptosis is a naturally occurring phenomenon in the developing mammalian brain both pre- and postnatally (Johnston et al., 2009). Apoptosis exhibits region specificity, showing variations in both quantity and latency (Nijhawan, Honarpour, & Wang, 2000; Rabinowicz, de Courten-Myers, Petetot, Xi, & de los Reyes, 1996; Rakic & Zecevic, 2000). As many as half of the cells generated during early development die by apoptosis, making the interplay between the successful establishment of appropriate connections with synaptic targets and the competition for antiapoptotic factors extremely important. Neurotrophic factors represent one group of factors capable of protecting developing neurons against apoptotic cascades (Nijhawan et al., 2000; Stiles & Jernigan, 2010).

Alcohol is a teratogen that is known to induce widespread apoptosis in CNS tissue at various developmental stages (Climent, Pascual, Renau-Piqueras, & Guerri, 2002; Dunty, Chen, Zucker, Dehart, & Sulik, 2001; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Olney et al., 2002). Exposure to alcohol during the gestational period in primates or the early postnatal period in rodents produces massive stimulation of apoptosis in the immature brain (Farber, Creeley, & Olney, 2010; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Olney et al., 2002). The mechanism of apoptosis includes the alcohol-driven decrease in neuronal activity in the developing brain through a suppression of glutamatergic NMDA receptors and potentiation of GABAergic receptors (discussed in Section 5.1), resulting in suppressed spontaneous network activity and the silencing of neurons in a dose-dependent manner (Lebedeva et al., 2015). Since synaptic activity is essential for neuronal survival during the gestational/early postnatal period, such silencing can result in activity-dependent apoptosis. Indeed, Ikonomidou et al. (2000) demonstrated a wide range of regional susceptibilities to alcohol-induced neurodegeneration following a single-day binge-like developmental exposure to ethanol. Furthermore, increased rates of apoptosis were found in hippocampi of rats exposed to alcohol in either a single-day or 2-day binge during third trimester equivalent (Smith, Guevremont, Williams, & Napper, 2015). Hippocampal cells displayed increased sensitivity to alcohol-induced neurodegeneration during the neonatal period (Heaton et al., 2003; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Livy, Miller, Maier, & West, 2003; Wozniak et al., 2004). Our lab’s unpublished data show that the rate of hippocampal apoptosis on PD5 (following a single day of binge alcohol exposure on PD4) is over 250% of the rate present in the normally developing brain at that age. Remarkably, the hippocampus has been shown to compensate for damage induced by ethanol through subsequent decreases in cell death and increases in adult neurogenesis. Smith and colleagues (2015) showed that animals exposed to ethanol on both PD6 and 8 displayed a reduced magnitude of apoptosis on PD8 relative to animals exposed to ethanol on PD8 only. Our data support these findings, indicating that apoptosis is decreased in CA1 of alcohol-exposed animals on PD8 (4 days after exposure). It is important to keep in mind that these compensatory events are not nearly as massive as the increase in cell death seen in the days immediately following the alcohol exposure. For the discussion of the role of neurotrophins in neuroprotection against apoptosis, see Section 7.

6.1.2 Adult Neurogenesis: Proliferation, Differentiation, Migration, and Cell Survival

Adult neurogenesis is the process through which the brain continues to generate new neurons throughout the life span in two specific regions: the sub-ventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricle and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Cells from the SVZ migrate via the rostral migratory stream to the olfactory bulb where they mature into interneurons, while most proliferating cells in the SGZ differentiate into dentate gyrus granule cells and migrate into the granule cell layer and integrate fully into the hippocampal trisynaptic pathway. This section will primarily focus on how neurotrophins and developmental alcohol exposure affect hippocampal adult neurogenesis, as this process is thought to be important for behaviors and cognition associated with the hippocampus, including spatial learning, context memory, pattern separation and completion, and emotion regulation. Performance on tasks that involve these dimensions of learning are often impaired in animal models of developmental alcohol exposure, and humans with FASDs often have significant learning disabilities (discussed in Section 6.2).

Adult neurogenesis is separated into stages of cell maturation: (1) proliferation, (2) differentiation, (3) migration, (4) maturation, and (5) long-term survival (dependent on successful synaptic integration). The entire process from cell birth to full integration takes up to 3 months. Neurotrophins are highly expressed in the adult rodent hippocampus and play an important role in all of these stages and work in synchrony for proper development, though certain neurotrophins seem to be more critical during certain maturation processes (Maisonpierre et al., 1990). BDNF is likely more important for later cell maturation, not initial proliferation, based on work showing that expression of the TrkB receptor is low during the first week following cell birth and increased as the cell ages (Donovan, Yamaguchi, & Eisch, 2008). Sairanen, Lucas, Ernfors, Castren, and Castren (2005) also reported that BDNF mutant mice displayed disrupted cell survival, even following administration of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) which increased new cell survival in wild-type mice. BDNF mutant mice also demonstrate stalled neuronal maturation and migration and reduced dendritic arborization in adult-born dentate gyrus cells (Chan, Cordeira, Calderon, Iyer, & Rios, 2008). VEGF has also been shown to play a role in adult neurogenesis, both indirectly through establishment of a neurogenic niche and by directly enhancing cell maturation processes (Licht et al., 2011).

Alcohol exposure during early development can impact both the health of neural progenitors in the adult rodent brain and the ability of these newly born granule cells to successfully mature and integrate into the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit, though the most consistent effects are reported on neuronal survival. Prenatal alcohol exposure decreased the size of the progenitor pool and number of proliferating neurons in one report (Redila et al., 2006) and a single binge on PD7 was shown to disrupt cell proliferation (Ieraci & Herrera, 2007). However, several other studies did not demonstrate an effect of alcohol on cell proliferation (Choi, Allan, & Cunningham, 2005; Gil-Mohapel et al., 2011; Hamilton et al., 2011; Klintsova et al., 2007). On the other hand, deficits in neuronal maturation processes and survival have been shown repeatedly (Gil-Mohapel et al., 2011; Hamilton et al., 2011; Ieraci & Herrera, 2007; Klintsova et al., 2007; Singh, Gupta, Jiang, Younus, & Ramzan, 2009), suggesting that alcohol exposure, particularly during the brain growth spurt period, permanently alters signaling pathways or gene expression necessary for successful maturation and synaptic integration. Ultimately, inability of the hippocampus to produce and integrate the number of new granule cells necessary for new memory formation could contribute to the cognitive deficits in children with FASDs and the behavioral impairments observed in animals models.

6.1.3 Dendritic Morphology and Spine Density

One avenue through which alcohol exposure could disrupt the ability of new cells in the hippocampus to successfully integrate is through alterations to dendritic spine density and complexity of the dendritic trees. Extension of neurites (dendrites toward the molecular layer and entorhinal cortex and axons toward CA3) is an essential step of granule cell maturation which begins when the cells are classified as immature neurons and can be immunolabeled with doublecortin (DCX). Formation of excitatory synapses with neurons located in the medial entorhinal cortex is a competitive process and a more complex dendritic tree increases the chances of functional connections being made. Even once a neuron is successfully integrated, decreased dendritic complexity and synapse number can impact efficiency of signal transduction within a brain region or circuit.

Neurotrophins play an important and well-orchestrated role in dendritic morphology and spine density throughout the brain. In the cortex, BDNF and NT-3 have been shown to oppose one another’s impact on dendritic structure depending on the cortical layer (McAllister, Katz, & Lo, 1997). In Layer IV, BDNF enhanced dendritic growth while NT-3 administration blocked this effect. In Layer VI, the roles were reversed, with BDNF inhibiting and NT-3 administration stimulating dendritic growth. BDNF has been repeatedly shown to enhance dendritic length and complexity in the hippocampus and in cell culture (Alonso et al., 2002; Singh et al., 2006; Tolwani et al., 2002) and conditional knockdown of BDNF in the mouse hippocampus decreases granule cell dendritic arborization (Chan et al., 2008). BDNF also increases spine density on CA1 dendrites (Alonso et al., 2002; Tyler & Pozzo-Miller, 2001). Aside from increasing spinogenesis, BDNF administration can cause spines to take on a more unstable, immature phenotype (Horch, Krüttgen, Portbury, & Katz, 1999; Shimada, Mason, & Morrison, 1998), possibly priming the dendrite for upcoming changes to intracellular signaling. The enhancing effects of BDNF are likely through action at the TrkB receptor, as activation of the p75 receptor seems to have the opposite effect of BDNF administration by decreasing dendritic complexity and spine density (Zagrebelsky et al., 2005). VEGF has recently been reported to be necessary for dendritic growth in new olfactory bulb neurons arising from progenitors in the SVZ, suggesting another new role for this neurotrophin (Licht et al., 2010).

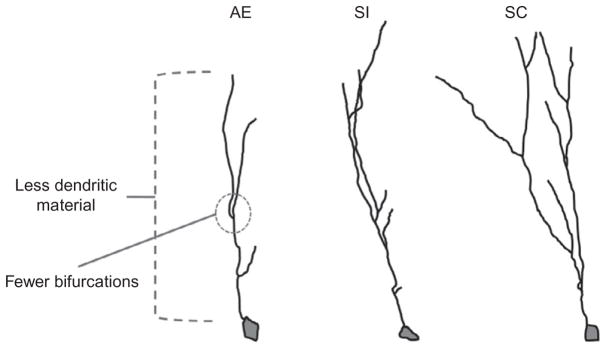

The exact mechanism through which developmental alcohol exposure compromises dendritic complexity in the adult brain is not well understood, but it is thought that these alterations contribute significantly to cognitive deficits in children with FAS. In fact, in cases of mental retardation due to either genetic or environmental factors, “dendritic abnormalities are the most consistent anatomical correlates” reported (Kaufmann & Moser, 2000). Third trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure has been shown to decrease basilar dendritic complexity in Layer II/III pyramidal neurons of the mPFC (Hamilton, Criss, & Klintsova, 2015; Hamilton, Whitcher, & Klintsova, 2010). Spine morphology on the basilar dendrites also shifted to a more mature, less plastic phenotype, though spine density was unchanged. On the other hand, the apical dendrites are affected in an almost opposite pattern by this model of alcohol exposure: dendritic tree morphology was stable but spine density was significantly decreased in alcohol-exposed animals (Whitcher & Klintsova, 2008). Perinatal alcohol exposure (combining pre- and postnatal exposure) had limited effect on dendritic structure in the nucleus accumbens, but reduced spine density on Layer II/III pyramidal cell dendrites in the mPFC (Lawrence, Otero, & Kelly, 2012). More recently, our lab has examined dendritic complexity of immature DCX+ dentate gyrus granule cells in the hippocampus of postnatally alcohol-exposed male Long–Evans rats using the Sholl analysis (Fig. 3). We have found that alcohol exposure (via intragastric intubation on PD4-9) significantly decreased the number of dendritic intersections and bifurcations per radius and decreased the amount of dendritic material per radius compared to control conditions (sham intubated and suckle control/undisturbed). Deficits in dendritic outgrowth at this stage of cell maturation could directly affect the neuron’s ability to successfully integrate into the hippocampal circuit and survive, in part contributing to the decreases in neuronal survival observed following third trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure (Klintsova et al., 2007). Prenatal alcohol exposure has not been found to affect spine density in hippocampal CA1 neurons in rats housed in isolation; however, alcohol-exposed rats housed in a complex “enriched” environment (which increases spine density in normal animals) display no change in spine density (Berman, Hannigan, Sperry, & Zajac, 1996). These findings suggest that timing of the alcohol exposure dictates whether baseline changes to dendritic complexity and spine density are present and that deficits might not be apparent until the system is challenged in some way. Overall, the abnormalities in dendritic morphology and spine density in alcohol-exposed animals likely contribute significantly to the behavioral deficits observed in rodent models of FASDs.

Fig. 3.

Third trimester-equivalent (postnatal days 4–9) alcohol exposure decreases dendritic complexity in immature dentate gyrus granule cells in the adult rat hippocampus. AE, alcohol-exposed (5.25 g/kg/day, binge-like exposure, intragastric intubation); SC, suckle control (undisturbed); SI, sham intubated (no liquid).

6.1.4 Microvasculature

Establishment and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier is essential to brain development, function, and plasticity. Neurotrophins enhance microvasculature and promote blood–brain barrier permeability. Treatment with BDNF prior to a spinal cord injury can even offer limited protection against injury through opening of the blood–spinal cord barrier (Sharma, 2003). BDNF is thought to have dual roles in enhancement of angiogenesis: promotion of endothelial cell survival through action at the TrkB receptor and through recruitment of immune cells to the site of an injury (Kermani & Hempstead, 2007). BDNF is an important part of ischemic injury repair in the skin, arterial, and cardiac tissues. NGF has been show to support angiogenesis in certain preparations as well (Cantarella et al., 2002). Perhaps the most important neurotrophin for the microcirculatory system and angiogenesis is VEGF, particularly for vasculogenesis during development. In addition, VEGF is critical in the formation and restructuring of blood vessels following injury, establishment of the neurogenic niche in the hippocampus, and tumorigenesis (Alvarez-Buylla & Lim, 2004; Ferrara, Gerber, & LeCouter, 2003; Rosenstein & Krum, 2004). VEGF has been tested as a protective agent in hypoxic or ischemic injury and VEGF antagonists have been put through trials to inhibit tumor growth (Ellis & Hicklin, 2008), though the success of these trials has been limited, not at least in part due to the complex timing of events during hypoxic injuries and mechanistic underpinnings of VEGF signaling that remain to be addressed.

Hypoperfusion of blood to target organs during embryonic development has been hypothesized to contribute to low birth weight and the cognitive impairments observed in children with FAS. This hypothesis has been supported by studies showing that children with FAS have lower cerebral blood flow, with considerable hypoperfusion of the temporal lobe specifically (Bhatara et al., 2002; Riikonen, Salonen, Partanen, & Verho, 1999). Similar findings have been borne out using animal models. Alcohol administration in adult rats decreased vasodilatory response to a variety of drugs that increase microvessel diameter in the healthy brain (Mayhan, 1992). In utero, alcohol-exposed fetuses experience reduced placental and arterial blood flow to the brain (Bake, Tingling, & Miranda, 2012; Jones, Leichter, & Lee, 1981). Inspection of brain sections taken from prenatally exposed mice revealed a disorganized and dying microvasculature (Jegou et al., 2012); death of the microvessels was prevented with administration of VEGF, supporting a neuroprotective role for this neurotrophin. Interestingly, cerebellar hyperperfusion was observed in fetal sheep following third trimester exposure (Parnell et al., 2007), which correlated with a reduction in Purkinje cell number. While most studies have found reduced cranial blood flow following prenatal alcohol exposure, the relationship between alcohol and the microcirculatory system is not always clear cut, and even areas that receive transiently increased blood flow can still show signs of alcohol-induced damage.

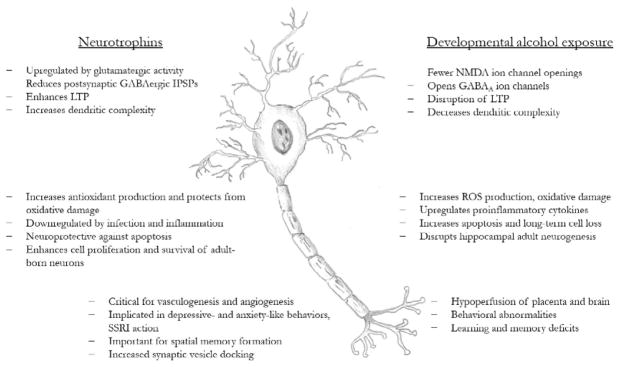

6.2 Behavioral Effects

Through actions on the molecular and anatomical systems of the brain, neurotrophin levels are correlated with a wide range of behavioral phenotypes. BDNF release in the hippocampus has been shown in multiple animal models to be required for short- and long-term contextual and spatial memory formation (Alonso et al., 2002; Griffin, Bechara, Birch, & Kelly, 2009; Lu & Chow, 1999). BDNF is rapidly upregulated during contextual memory formation (Hall, Thomas, & Everitt, 2000) and blockade of hippocampal BDNF release impairs the ability of mice to form hippocampus-dependent memories (Heldt, Stanek, Chhatwal, & Ressler, 2007). Exercise, which robustly enhances neurotrophin production in the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex, also improves performance on both spatial and nonspatial memory tasks (Griffin et al., 2009). Supporting the role of BDNF in the behavioral enhancements, injection of BDNF directly into the cerebroventricular system resulted in the same augmentation to memory. Mechanistically, BDNF increases levels of docked synaptic vesicles and neurotransmitter release, leading to enhanced LTP induction and maintenance, making BDNF a critical variable in the synaptic and cellular changes underlying memory formation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the overlapping effects of alcohol exposure during development and neurotrophin action on brain structure and function. Numbers indicate the section of the chapter’s text which include references for each point.

Neurotrophin dysregulation has also been implicated in anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors in rodent models of mood disorders (Martinowich, Manji, & Lu, 2007; Fig. 4). Some studies have found that decreases in BDNF have been correlated with behavioral phenotypes of depression and anxiety, but often these effects are small and inconsistent between models and differ between male and female animals. More convincing is the upregulation of BDNF following antidepressant treatment with SSRIs, and evidence suggests that regulation of BDNF expression and signaling is a downstream target of these drugs. Bdnf mutant mice that express increased anxiety-like behaviors did not show improvements following treatment with SSRIs, suggesting BDNF upregulation as a key component of antidepressant action (Chen et al., 2006). In humans, the Val66Met polymorphism has been linked to reduced hippocampal volume and the development of psychopathologies including depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia (Martinowich et al., 2007; Sanchez et al., 2011). This single-nucleotide polymorphism refers to a methionine (Met) substitution for valine (Val) in the prodomain (codon 66) of the BDNF protein and disrupts activity-dependent release of BDNF (Chen et al., 2005). While the Val66Met polymorphism increases an individual’s genetic risk for developing psychopathology, experiencing early life stress or trauma can enhance this risk (Gatt et al., 2009). Mouse models of this polymorphism (BDNFMet/Met) also show increased anxiety-related behaviors, including reductions in time spent in the center of an open field and in the open arms of an elevated plus maze (Chen et al., 2006). These behavioral changes were not reversed with administration of an SSRI and were accompanied by decreased hippocampal volume and dendritic complexity.

Children with FASDs exhibit both scholastic and intellectual disabilities (Mattson et al., 1999; Mattson, Riley, Delis, et al., 1996; Mattson et al., 1997; Mattson, Riley, Sowell, et al., 1996; Rasmussen et al., 2011), as well as abnormal social and emotional interactions. As adults, individuals with FASDs are more likely to have trouble with the law, in part due to executive functioning and impulse control deficits (Franklin et al., 2008; Irner et al., 2012; Kodituwakku et al., 1995; Pei et al., 2011; Stevens et al., 2012; Streissguth et al., 2004). To some degree, the learning and memory dysfunctions observed in humans with FASDs (Uecker & Nadel, 1996) have been modeled in animals as well. In animal models, alcohol-induced alterations to behavioral endpoints are largely dependent on the timing and dose of the exposure; however, both prenatal and postnatal models can significantly disrupt hippocampal-associated behavior (Berman & Hannigan, 2000; Clements, Girard, Ellard, & Wainwright, 2005; Hamilton, Boschen, Goodlett, Greenough, & Klintsova, 2012; Hunt, Jacobson, & Torok, 2009; O’Leary-Moore, McMechan, Mathison, Berman, & Hannigan, 2006; Thomas, Weinert, Sharif, & Riley, 1997). These deficits include impairment on spontaneous alternation tasks, the Morris Water Maze, the radial arm maze, discrimination and reversal learning, and variants of fear conditioning. Third trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure impairs the ability of rats to learn a novel context and reduces novelty-associated c-Fos expression in hippocampal CA1 (Murawski, Klintsova, & Stanton, 2012).

Beyond performance on spatial memory tasks, alcohol-exposed animals also show alterations to social and anxiety behaviors (Fig. 4). Third trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure reduced exploratory and play behaviors in adolescent rats housed in a complex environment with enhanced social and novelty-related stimulation (Boschen, Hamilton, Delorme, & Klintsova, 2014), and alcohol-exposed rats also show altered play fighting and decreased social recognition behaviors in other social interaction paradigms (Kelly & Dillingham, 1994; Kelly, Leggett, & Cronise, 2009; Middleton, Varlinskaya, & Mooney, 2012; Mooney & Varlinskaya, 2011). Children with FAS likewise show social behavior deficits which present independent of changes to IQ (Thomas, Kelly, Mattson, & Riley, 1998). There is some evidence that alcohol-exposed animals also show anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors, such as increased learned helplessness and immobility during the forced swim test, which were correlated with downregulation of Bdnf expression in the mPFC and hippocampus (Caldwell et al., 2008; Hellemans, Verma, Yoon, Yu, & Weinberg, 2008). Depression is also more commonly diagnosed in children with documented prenatal alcohol exposure compared to age-matched controls (Roebuck, Mattson, & Riley, 1999). Increased presentation of psychopathology is apparent from early childhood and the risk continues through adolescence, at the least (O’Connor & Kasari, 2000; O’Connor & Paley, 2006; Steinhausen & Spohr, 1998). Like social functioning deficits, anxiety and depression are associated with prenatal alcohol exposure even if the children had a normal IQ and performance other measures of intelligence. Whether the increased propensity of children with prenatal alcohol exposure to develop depression and anxiety is related to altered neurotrophin functioning within the prefrontal cortex or limbic areas remains to be investigated.

7. NEUROTROPHINS AS COMPENSATORY/NEUROPROTECTIVE MOLECULES FOLLOWING DEVELOPMENTAL ALCOHOL EXPOSURE

While BDNF and other neurotrophins have been long investigated for their role in neuroprotection, future work must continue to explore neurotrophins as compensatory molecules during or following developmental alcohol exposure (Davis, 2008; Idrus & Thomas, 2011; Pezet & Malcangio, 2004). As discussed earlier, alcohol exposure induces widespread waves of apoptosis throughout the developing brain shortly following administration. BDNF prevents apoptosis in a variety of experimental paradigms, including excitotoxicity and ischemic hypoxia (Almeida et al., 2005; Han & Holtzman, 2000). There is also evidence that pharmacological modulation of NGF and BDNF can protect against cytotoxicity and apoptosis following alcohol exposure, though this effect has only been directly demonstrated in vitro. Both BDNF and NGF reduced cytotoxicity as measured by a reduction in 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide in a model of ethanol exposure combined with hypoxia and hypoglycemia (Mitchell, Paiva, Walker, & Heaton, 1999). Administration of alcohol to cultured human neuroblastomas decreased cell viability (mitochondrial activity) and BDNF and CREB levels; exogenously applied BDNF improved mitochondrial activity in alcohol-exposed cells (Sakai et al., 2005). Alcohol induced apoptosis in cerebellar granule cells, but the upregulation of cell death was blocked by BDNF (Bhave et al., 1999). Finally, Climent et al. (2002) showed that BDNF activated anti-apoptotic and procell survival pathways in the postnatal cerebral cortex; however, this activation is disrupted by prenatal alcohol exposure. Further research needs to be done to determine if these results hold true in vivo. Numerous studies have found enhanced levels of neurotrophins in the hippocampus and cortex within 24 h of alcohol administration, suggesting a possible endogenous mechanism of neuroprotection (Boschen et al., 2015; Heaton et al., 2000, 2003). This enhancement may be timing and region specific and temporally restricted, with possible links to alcohol withdrawal. It is not known if blocking this upregulation of neurotrophins would further alcohol-related cell loss or which isoform of BDNF protein is increased (pro vs mature BDNF).

While administration of exogenous neurotrophic factors to cultured cells has shown some therapeutic promise, little work has been done exploring administration of neurotrophins to alcohol-exposed rodents, possibly due to logistical or technical issues (Davis, 2008). The neuroprotective effect of neurotrophic factors would depend largely on timing of administration following the alcohol exposure. To achieve true protection from the negative effects of alcohol, the neurotrophin would be administered either shortly before or during the alcohol exposure, or possibly during the withdrawal period. BDNF infused intracerebroventricularly to mice exposed prenatally to alcohol and stress has positive benefits on anxiety-like behavior (marble burying) and aberrant sexual and social interactions (Popova, Morozova, & Naumenko, 2011); however, these effects were only apparent following 7–10 days of daily infusions. Incerti, Vink, Roberson, Benassou, et al. (2010) and Incerti, Vink, Roberson, Wood, et al. (2010) reported that embryos exposed to alcohol on GD8 had decreased levels of BDNF after 6 h and enhanced levels after 24 h; BDNF levels were normalized with neuropeptides related to vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP). Administration of these neuropeptides in adulthood reversed alcohol-induced learning deficits (Incerti, Vink, Roberson, Benassou, et al., 2010; Incerti, Vink, Roberson, Wood, et al., 2010). VIP and BDNF have been shown to reciprocally enhance expression of one another in certain cell types (Cellerino, Arango-Gonzalez, Pinzon-Duarte, & Kohler, 2003; Pellegri, Magistretti, & Martin, 1998). Recently, other pharmacological agents including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ), which suppresses production of proinflammatory cytokines (Drew et al., 2015) and lithium (Luo, 2010) have shown promise in protecting against alcohol-induced cytotoxic damage. Lithium, for one, is known to enhance neurotrophin levels, and activation of the neuroimmune response can downregulate BDNF expression, calling for future research to determine if these drugs exert action, at least in part, through neurotrophin signaling.

Neuropharmacological approaches to increase neurotrophin availability in order to promote neuroprotection against alcohol toxicity provide a quick, but invasive possible solution. Other therapeutic interventions known to naturally enhance neurotrophin expression in the brain present a very valuable avenue to have the brain potentially heal itself. Such therapies include the “usual suspects”: exercise, learning experience, environmental stimulation, and dietary restriction (Bekinschtein, Oomen, Saksida, & Bussey, 2011; Cotman & Berchtold, 2007; Lee, Seroogy, & Mattson, 2002; Russo-Neustadt, Beard, & Cotman, 1999). Indeed, the first three interventions have been extensively in animal models of developmental alcohol exposure to produce improvements in behavioral outcomes and neuroanatomical parameters (Hamilton et al., 2012, 2014; Hannigan, Berman, & Zajac, 1993; Helfer, Goodlett, Greenough, & Klintsova, 2009; Klintsova et al., 2002; Redila et al., 2006; Thomas, Sather, & Whinery, 2008). It has been demonstrated that ethanol-mediated damage can be powerfully modulated by neurotrophins (Heaton, Madorsky, Paiva, & Mayer, 2002), which are upregulated by the interventions listed. Incorporating exercise, increased novelty and social stimulation, and careful diet regulation as part of a therapeutic program for children with FASDs could help the brain produce more neurotrophins, promote neuroplasticity, and mitigate at least some of the alcohol-induced deficits to cognition and behavior.

8. CONCLUSIONS

FASDs are devastating for children, families, and communities, and completely preventable through the avoidance of alcohol during pregnancy. Despite increased public awareness and safety campaigns from government and medical agencies, the rate of FASDs has not decreased significantly in recent years. Development of pharmacological and behavioral interventions for children with FASDs is an important step in helping these individuals gain functional independence and alleviate the emotional and monetary burden of care from the families and society. Exposure to alcohol during development can impact the production and function of neurotrophins, which represents both a mechanism of alcohol-induced brain damage and a potential avenue of therapeutic intervention which remains to be fully explored. There are also numerous processes which seem to be affected by both alcohol and neurotrophins or which could represent mechanisms through which alcohol-induced changes could then alter neurotrophin levels, such as oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Both of these areas of research have many open questions remaining. Further investigation of neurotrophins as neuroprotective molecules in the alcohol-damaged brain could lead to the development of new therapeutic alternatives for children with FASDs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank P.T. Boschen for the illustrations in this chapter and K.J. Criss and T.F. Gamage for assistance in editing the manuscript. The dendritic morphology and apoptosis work was supported by NIH/NIGMS COBRE: The Delaware Center for Neuroscience Research Grant 1P20GM103653 to A.Y.K.

References

- Allen GC, West JR, Chen WJ, Earnest DJ. Developmental alcohol exposure disrupts circadian regulation of BDNF in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2004;26(3):353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.02.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ntt.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida RD, Manadas BJ, Melo CV, Gomes JR, Mendes CS, Graos MM, … Duarte CB. Neuroprotection by BDNF against glutamate-induced apoptotic cell death is mediated by ERK and PI3-kinase pathways. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2005;12(10):1329–1343. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401662. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloe L, Bracci-Laudiero L, Tirassa P. The effect of chronic ethanol intake on brain NGF level and on NGF-target tissues of adult mice. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1993;31(2):159–167. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso M, Vianna MR, Depino AM, Mello e Souza T, Pereira P, Szapiro G, … Medina JH. BDNF-triggered events in the rat hippocampus are required for both short- and long-term memory formation. Hippocampus. 2002;12(4):551–560. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10035. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hipo.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA. For the long run: Maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron. 2004;41(5):683–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendah DD, Grosse SD, Bertrand J. Medical expenditures of children in the United States with fetal alcohol syndrome. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2011;33(2):322–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.10.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ntt.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Gamst A, Riley EP, Mattson SN, Jernigan TL. Brain dysmorphology in individuals with severe prenatal alcohol exposure. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2001;43(3):148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]