Abstract

Substance abuse is serious public health problem for which there are few effective pharmacotherapies. Traditional strategies for drug development have focused on antagonists to block the abuse-related effects of a drug at its site of action, and agonists to replace/mimic the effects of the abused substance. However, recent efforts have targeted receptors, such as serotonin (5-HT)2 receptors, that can indirectly modulate dopamine neurotransmission with the goal of developing a pharmacotherapy that might be effective at reducing the abuse-related effects of drugs more generally. Lorcaserin is a 5-HT2C receptor-preferring agonist that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of obesity. Mounting evidence from preclinical and clinical studies suggests that lorcaserin might also be effective at reducing the abuse-related effects of drugs with different pharmacological mechanisms (e.g., cocaine, heroin, ethanol, and nicotine). Lorcaserin represents a promising and important first step towards the development a new class of pharmacotherapies that have the potential to dramatically improve the treatment of substance abuse. This article will review the behavioral pharmacology of 5-HT2C receptor-preferring agonists, with a focus on lorcaserin, and evaluate the preclinical evidence supporting the development of lorcaserin for treating substance abuse.

1. INTRODUCTION1

The recreational use/abuse of drugs remains a significant public health problem, with worldwide estimates suggesting that 1 out of every 20 adults, or a quarter of a billion people, abused at least one drug (e.g., cocaine) in 2014 (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2016). Although the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved drugs to treat substance use disorders (e.g., methadone or naltrexone for opioid abuse, and bupropion or varenicline for cigarette smoking), there are currently no FDA-approved pharmacotherapies for the abuse of stimulants, such as cocaine or methamphetamine. Drugs of this class interact with dopamine (DAT), serotonin (SERT), and norepinephrine (NET) transporters where they either inhibit monoamine uptake (e.g., cocaine) or stimulate monoamine release (e.g., methamphetamine); however, their abuse-related effects are mediated predominantly by their capacity to increase dopamine neurotransmission, particularly within the nucleus accumbens (Ritz et al., 1987). Because of this central role of dopamine, drugs targeting dopamine systems have received considerable attention as candidate medications for cocaine abuse, and generally fall into one of three general categories: 1) direct- and indirect-acting dopamine receptor agonists, which aim to provide a replacement drug for cocaine (e.g., Grabowski et al., 2004; Negus & Henningfield, 2015); 2) cocaine “antagonists”, which aim to block/reduce the actions of cocaine at DAT (e.g., Rothman et al., 2008; Tanda et al., 2009); and 3) modulators of cocaine, which aim to alter the effects of cocaine through actions at sites other than DAT (e.g., Dackis & O’Brien, 2003; Mello, 1990; Newman et al., 2005; Roberts & Brebner, 2000). It is well established that serotonin (5-HT) systems modulate dopamine activity, and this review focuses on the effectiveness of lorcaserin, a 5-HT2C receptor-preferring agonist, to reduce the abuse-related effects of cocaine, and other drugs of abuse.

Although the modulatory effects of drugs acting on a variety of neurotransmitter systems (e.g., gamma-aminobutyric acid [GABA], glutamate, and opioid) have been evaluated, to date there are no effective medications for stimulant abuse. Mounting evidence suggests that drugs acting on 5-HT systems could provide a safe and effective approach for treating stimulant abuse. In particular, because 5-HT2 receptors play important roles in modulating dopamine neurotransmission (for review see Howell & Cunningham, 2015), a number of 5-HT2A receptor antagonists and 5-HT2C receptor agonists have been evaluated for their capacity to decrease stimulant self-administration and/or prevent the reinstatement of responding by drug-associated stimuli and/or priming injections of the drug itself (e.g., Grottick et al., 2000; Fletcher et al., 2002; 2004; Nic Dhonnchada et al., 2009; Murnane et al., 2013). Importantly, in 2012 the US FDA approved lorcaserin, a 5-HT2C receptor-preferring agonist, for the treatment of obesity in adults. Subsequently, lorcaserin has shown positive effects in 11 preclinical studies evaluating its capacity to decrease the self-administration of nicotine (Levin et al., 2011; Higgins et al., 2012; Cousins et al., 2014; Zeeb et al., 2015; Briggs et al., 2016), ethanol (Rezvani et al., 2014), opioids (Neelakantan et al., 2017), or stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine (Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016; Collins et al., 2016; Gerak et al., 2016), although Banks & Negus (2017) report that lorcaserin did not alter the allocation of responding in a cocaine versus food choice paradigm. It should be noted, however, that the majority of these effects (Levin et al., 2011; Cousins et al., 2014; Rezvani et al., 2014; Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016; Neelakantan et al., 2017) were observed at doses of lorcaserin that have been shown to produce behavioral effects mediated by 5-HT2A receptors (Serafine et al., 2015; Serafine et al., 2016). Together, these findings raise the possibility that doses of lorcaserin larger than those currently approved for use in humans (10 mg, twice daily; BID) might be required to effectively treat substance abuse.

2. BASIC PHARMACOLOGY OF 5-HT2 RECEPTORS

To date, 14 distinct subtypes of 5-HT receptors (11 G protein-coupled receptors, and 3 ligand gated ion channels [5-HT3A-C receptors]) have been identified, with the structural and functional properties of these receptors further subdividing them into one of seven families of 5-HT receptors (i.e., 5-HT1 through 5-HT7; for review, see Hannon & Hoyer, 2008). The 5-HT2 family of receptors includes the 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors, each of which couple to Gaq/11 G proteins. Of note, 5-HT2C receptor pre-mRNA contains 5 sites that are capable of undergoing adenosine to inosine editing, a process that is regulated by 5-HT and can result in the expression of up to 24 different isoforms of the 5-HT2C receptor (Gurevich et al., 2002). 5-HT2A receptors are expressed in brain regions known to be important for perception (neo-cortex), motor control, motivation, and reward (pontine nuclei and basal ganglia), whereas 5-HT2C receptors are expressed in the choroid plexus, and in brain regions important for the regulation of feeding (hypothalamus), as well as motor control, motivation, and reward (basal ganglia; Hannon & Hoyer, 2008). Unlike 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors, 5-HT2B receptors are primarily expressed in the periphery (gut, heart, kidney, and lung) with only limited expression in the central nervous system (Hannon & Hoyer, 2008). Although 5-HT2A/2B/2C receptors all couple to Gaq/11 G proteins, differences in their patterns of expression as well as differences in the functional potency of 5-HT at 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors (31 nM, 2.1 nM, and 5.8 nM, respectively; Porter et al., 1999) contribute to differences in the behavioral pharmacology and clinical indications for 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptor-preferring agonists and antagonists.

In humans, 5-HT2A receptor agonists alter cognition and perception in a manner that is often referred to as a psychedelic effect, whereas 5-HT2A receptor antagonists (e.g., clozapine) and inverse agonists (e.g., pimavanserin) have antipsychotic properties and have also been evaluated as potential treatments for addiction. Although the development of drugs with psychedelic properties as pharmacotherapies has long been controversial, there is renewed interest in their potential to treat a variety of diseases including depression, anxiety, and addiction, as well as a number of inflammatory conditions (discussed elsewhere in this special issue). Because chronic activation of 5-HT2B receptors has been linked to cardiovascular valvopathy (Rothman & Baumann, 2009; Hutchenson et al., 2011), agonist actions at 5-HT2B receptors are avoided in the development of potential therapeutics; however, 5-HT2B receptor antagonists have been developed as potential treatments for migraine and heart disease. Based in large part on evidence that 5-HT2C receptors mediate the hypophagic effects of direct- and indirect-acting 5-HT receptor agonists (Kennett & Curzon, 1991; Tecott et al., 1995; Vickers et al., 2001), significant efforts have been devoted towards developing selective 5-HT2C receptor agonists in the hopes of identifying drugs that decrease appetite without also producing hallucinations (5-HT2A receptor-mediated) and/or cardiovascular toxicities (5-HT2B receptor-mediated) that can occur with less selective and/or indirect-acting 5-HT drugs. Interestingly, and of direct relevance to this review, 5-HT2C receptor agonists also decrease the intravenous self-administration of a variety of drugs (i.e., cocaine, methamphetamine, nicotine, opioids, and alcohol) (Grottick et al., 2000; Fletcher et al., 2004, 2008; Levin et al., 2011; Cunningham et al., 2011; Manvich et al., 2012a; Cousins et al., 2014; Rezvani et al., 2014; Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016; Collins et al., 2016; Gerak et al., 2016; Neelakantan et al., 2017), suggesting that they might be effective for treating a range of substance use disorders. Although inhibition of 5-HT2C receptors is a property of many atypical antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine) and antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline), 5-HT2C receptor antagonists have been shown to have mild stimulant properties (Manvich et al., 2012b), presumably because of interactions between 5-HT2C receptors and dopamine neurotransmission.

2.1. REGULATION OF DOPAMINE NEUROTRANSMISSION BY 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C RECEPTORS

Serotonin systems play an important and well-documented role in modulating goal-directed behaviors, such as feeding and drug self-administration. Although the anti-obesity effects of 5-HT2C receptor selective agonists appear to be mediated by receptors on pro-opiomelanocortin neurons located in brain regions important for feeding (e.g., dorsomedial and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus), the anti-addiction effects of 5-HT2A receptor antagonists and 5-HT2C receptor agonists are thought to be mediated by their capacity to modulate mesolimbic dopamine neurotransmission (see Howell & Cunningham, 2015 for review). Briefly, 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors exhibit a partially overlapping pattern of expression on dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons within brain regions important for reward and reinforcement, including the ventral tegmental area, prefrontal cortex, and nucleus accumbens. Importantly, these patterns of distribution allow 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors to play important, although functionally opposite, roles in controlling dopamine neurotransmission, with 5-HT2A receptor agonists stimulating, and 5-HT2C receptor agonists inhibiting, the activity of dopamine systems under basal and activated conditions (see Howell & Cunningham, 2015 for review and references therein). Specifically because of their capacity to dampen the activity of mesolimbic dopamine systems, 5-HT2A receptor antagonists and inverse agonists, as well as 5-HT2C receptor agonists, have been evaluated as pharmacotherapies for substance abuse.

3. EFFECTS OF 5-HT2A AND 5-HT2C RECEPTOR LIGANDS IN PRECLINICAL MODELS OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Two of the most widely used procedures to model substance abuse in laboratory animals are intravenous self-administration, which provides a direct measure of drug reinforcement, and the reinstatement of extinguished responding that was previously maintained by drug, which is thought to model behaviors relevant to relapse. Intravenous self-administration is a procedure in which laboratory animals (e.g., mice, rats, monkeys) can respond (e.g., press a lever) to receive an infusion of drug. In addition to being the gold standard for evaluating the abuse liability of drugs (O’Connor et al., 2011), self-administration procedures are also well suited to evaluate candidate medications to aid in the cessation of drug taking. Although the capacity to decrease ongoing self-administration (i.e., drug reinforcement) is a desirable property for candidate medications to treat substance abuse, it is perhaps equally important for these drugs to prevent relapses to drug taking once abstinence is established. To this end, numerous variations of the reinstatement model of relapse (deWit & Stewart, 1981) have been widely used to evaluate the effectiveness of candidate medications to inhibit the capacity of drug-associated stimuli and/or non-contingent infusions of drug to increase/reinstate a previously extinguished drug-taking response.

Although 5-HT2A receptor antagonists (e.g., ketanserin, MDL100907), and inverse agonists (e.g., pimavanserin) appear to be more effective at reducing the reinstatement of extinguished responding, than at decreasing the ongoing self-administration of drugs, such as cocaine, MDMA, and nicotine (Lacosta & Roberts, 1993; Howell & Byrd, 1995; Fletcher et al., 2002; 2012; Nic Dhonnchada et al., 2009; Pockros et al., 2011; Murnane et al., 2013; Cousins et al., 2014; Schenk et al., 2016; Banks & Negus, 2017; but see Fantegrossi et al., 2002), 5-HT2C receptor agonists appear to be effective in both the self-administration and reinstatement models of substance abuse. With regard to the development of 5-HT2C receptor agonists as pharmacotherapies for substance abuse, the vast majority of preclinical evidence supporting this indication is from studies using Ro 60-0175, an agonist that is ~14-fold selective for 5-HT2C over 5-HT2A receptors in vitro (Table 1). In addition to decreasing the self-administration of cocaine and nicotine, Ro 60-0175 has been shown to reduce the reinstatement of extinguished responding previously maintained by either cocaine or nicotine (Grottick et al., 2000; Fletcher et al., 2004; 2008; 2012; Manvich et al., 2012a; Higgins et al, 2013a; Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2015). Consistent dose-dependent decreases in the self-administration of cocaine, as well as the inhibition of these effects by the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist SB 242,084 (Table 1), provides strong support for the 5-HT2C receptor hypothesis; however, the fact that Ro 60-0175 is more potent at 5-HT2B than 5-HT2C receptors (Table 1) suggests that its translational potential would likely be limited by cardiovascular toxicities (Launay et al., 2002), thus highlighting the need for more selective 5-HT2C receptor agonists.

Table 1.

Radioligand binding and functional potency measures for 5-HT2 receptor agonists and antagonists

| 5-HT2A | 5-HT2B | 5-HT2C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonists | EC50 (nM) | Efficacy % 5-HT | EC50 (nM) | Efficacy % 5-HT | EC50 (nM) | Efficacy % 5-HT | 2A/2C | 2B/2C |

| 5-HTa | 31 | 102 | 2.1 | 106 | 5.8 | 97 | 5.3 | 0.4 |

| Ro 60-0175a | 447 | 69 | 8.9 | 79 | 32 | 84 | 14 | 0.3 |

| Lorcaserinb | 168 | 100 | 943 | 75 | 9 | 100 | 19 | 105 |

|

| ||||||||

| Efficacy | Efficacy | Efficacy | ||||||

| Antagonist | Ki (nM) | % 5-HT | Ki (nM) | % 5-HT | Ki (nM) | % 5-HT | 2A/2C | 2B/2C |

|

| ||||||||

| SB 242084c | 158 | n.d. | 100 | n.d. | 1 | n.d. | 158 | 100 |

| MDL100907d | 0.85 | n.d. | 261 | n.d. | 136 | n.d. | 0.006 | 1.9 |

EC50 values determined by FLIPR in CHO-K1 cells expressing human 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, or 5-HT2C receptors with efficacy determined relative to 10 μM 5-HT, Porter et al., 1999

EC50 values determined by inositol phosphate accumulation assays in HEK293 cells expressing human 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, or 5-HT2C receptors with efficacy determined relative to 10 μM 5-HT, Thomsen et al., 2008

Ki values determined by radioligand binding studies in HEK293 cells expressing human 5-HT2A ([3H]-ketanserin), 5-HT2B ([3H]-5-HT), or 5-HT2C ([3H]-mesulergine) receptors, Kennett et al., 1997

Ki values for PDSP certified radioligand binding studies with human 5-HT2A ([3H]-ketanserin), 5-HT2B ([3H]-LSD), or 5-HT2C ([3H]-mesulergine) receptors, kidbdev.med.unc.edu/databases/kidb.php.

3.1. LORCASERIN AS A CANDIDATE MEDICATION FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE

In 2008, Arena Pharmaceuticals reported lorcaserin to be a 5-HT2C receptor agonist with modest selectivity over 5-HT2A receptors (~19-fold), substantial selectivity over 5-HT2B receptors (~100-fold; Table 1) based on in vitro functional assays, and good pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties that resulted in the reduction of food intake and body weight gain in rats (Thomsen et al., 2008). Importantly, lorcaserin also proved effective at decreasing body weight in a multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trial (Smith et al., 2010) and, after receiving approval from the US FDA in 2012, was marketed as Belviq® for treating obesity in adults. In addition to providing a novel treatment for obesity, the approval of lorcaserin for use in humans facilitated the opportunity to evaluate very rapidly the effectiveness of a 5-HT2C receptor agonist to decrease substance abuse. Indeed, in the 5 years since its approval, lorcaserin has been shown to consistently decrease the abuse-related effects of a variety of drugs (cocaine, methamphetamine, nicotine, alcohol, and opioids), and these positive preclinical results have resulted in a number of clinical trials that are evaluating lorcaserin for the treatment of substance use disorders (clinicaltrials.gov).

Early studies focused on the capacity of lorcaserin to alter nicotine self-administration in rats, with lorcaserin producing consistent and dose-dependent decreases in responding for 0.03 mg/kg/infusion nicotine. Levin and colleagues reported minimally effective doses of lorcaserin ranging from 0.3-1.25 mg/kg (Levin et al., 2011; Cousins et al., 2014; Briggs et al., 2016), whereas Higgins and colleagues (2012) reported a minimally effective dose of 1 mg/kg. Importantly, Higgins and colleagues (2012) also reported that a smaller dose of lorcaserin (0.3 mg/kg) inhibited the reinstatement of extinguished responding for nicotine, and that the effects of lorcaserin in both of these assays (self-administration and reinstatement) were antagonized by 0.5 mg/kg of the 5-HT2C receptor selective antagonist SB 242,084. Although these findings provided strong evidence that agonist actions at 5-HT2C receptors can decrease nicotine self-administration, the capacity of lorcaserin to inhibit responding maintained by intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS), an effect that was blocked by the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist SB 242,084 (Zeeb et al., 2015), suggests a more general role for 5-HT2C receptors in modulating brain systems important for reward. Consistent with this notion, lorcaserin is roughly equipotent at decreasing responding for either nicotine or food in rats, with reports showing that lorcaserin is ~1.6-fold more potent at decreasing responding for food relative to nicotine (Higgins et al. 2012), or ~2-fold more potent at decreasing responding for nicotine relative to food (Briggs et al., 2016).

Although the majority of studies with lorcaserin that used rodents have investigated interactions between lorcaserin and nicotine, recent studies have extended those findings to the consumption of ethanol (Rezvani et al., 2015) as well as the self-administration of cocaine (Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016) or oxycodone (Neelakantan et al., 2017). As was observed with nicotine, lorcaserin dose-dependently decreased the consumption of ethanol, the self-administration of cocaine or oxycodone, and the reinstatement of extinguished responding for cocaine or oxycodone in rats, with minimally effective doses ranging from 0.6-1 mg/kg. Importantly, these effects of lorcaserin were also antagonized by 0.5 mg/kg SB 242,084 (Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016; Neelakantan et al., 2017), consistent with the notion that the abuse-related effects of cocaine and oxycodone can be modulated by activation of 5-HT2C receptors.

Recent studies in rhesus monkeys extend these findings and provide additional support for using lorcaserin to treat stimulant abuse (Collins et al., 2016; Gerak et al., 2016). As shown in Figure 1A, acute, intra-gastric (IG) administration of lorcaserin dose-dependently decreased the self-administration of 0.032 mg/kg/infusion cocaine, with doses of 1 and 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin decreasing response rates by ~50% and ~80%, respectively (Collins et al., 2016). Although lorcaserin also decreased responding maintained by food, these effects occurred at doses ~5-fold larger than those required to decrease responding for cocaine (Figure 1A). Further evidence that lorcaserin is capable of decreasing the reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine was provided by studies in which the acute administration of lorcaserin (3.2 mg/kg) produced a ~7-fold rightward shift in the cocaine dose-response curve in monkeys responding under a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement (Figure 1B; also see Gerak et al., 2016). Together with the finding that lorcaserin dose-dependently inhibited the reinstatement of extinguished responding for cocaine in monkeys (Figure 1C; Gerak et al., 2016), these findings suggest that lorcaserin might facilitate quit attempts by not only reducing the reinforcing effects of cocaine, but also by preventing relapse to cocaine use.

Figure 1.

Summary of the effects of acute (A-C) and repeated (D-F) intra-gastric (IG) administration of lorcaserin on responding maintained by various stimuli in rhesus monkeys. A) Acute administration of lorcaserin dose dependently decreases the rates of responding maintained by 0.032 mg/kg/infusion cocaine (FR30:TO 180-sec) and food pellets (FR10); B) acute administration of lorcaserin (3.2 mg/kg) produces a rightward shift of the dose-response curve for cocaine self-administration under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement; C) acute administration of lorcaserin dose dependently decreases the reinstatement of extinguished responding (above EXT) for cocaine (FR30:TO 180-sec; above BL) by cocaine-associated stimuli alone (above CS) and in conjunction with non-contingent cocaine administration (above 0.1, 0.32, 1 mg/kg cocaine); D) repeated, daily administration of lorcaserin (3.2 mg/kg) produces a sustained decrease the rate of responding for 0.032 mg/kg/infusion cocaine (FR30:TO 180-sec) (open circles), with baseline levels of responding recovered when lorcaserin treatment is replaced with saline (filled circles); E) repeated, daily administration of lorcaserin (3.2 mg/kg) produces a sustained decrease the number of cocaine infusions (0.032 mg/kg) earned under a PR schedule of reinforcement (open circles), with baseline levels of responding recovered when lorcaserin treatment is replaced with saline (filled circles); F) repeated, daily administration of lorcaserin (3.2 mg/kg) produces a sustained decrease in the peak rates of responding for methamphetamine (FR30:TO 60-sec) (open circles), with baseline levels of responding recovered when lorcaserin treatment is replaced with saline (filled circles). Data in panels A and D were replotted with permission from Collins et al., 2016. Data in panels B, C, E, and F were replotted with permission from Gerak et al., 2016.

While these findings are consistent with reports from rodents and suggest that the acute administration of lorcaserin yields positive effects in two important preclinical models of substance abuse, it is important to remember that addiction is a chronic disease, typically requiring patients to remain on treatments long-term in order to maintain abstinence. Accordingly, we and others have also evaluated the capacity of lorcaserin to alter the self-administration of drugs such as cocaine, nicotine, and methamphetamine following repeated, daily, or continuous administration (Levin et al., 2011; Collins et al., 2016; Gerak et al., 2016; Banks & Negus, 2017). As shown in Figure 1D, when administered at a daily dose of 3.2 mg/kg (IG), lorcaserin decreased responding in monkeys self-administering 0.032 mg/kg/infusion cocaine under a fixed ratio (FR) 30 schedule of reinforcement to ~50% of baseline across the entire 14-day treatment period. Importantly, not only were similarly persistent results obtained when monkeys self-administered cocaine under a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement (Figure 1E) or methamphetamine under an FR30 schedule of reinforcement (Figure 1F), but in each case responding returned to baseline levels within the first two sessions after terminating daily treatment with lorcaserin (Figure 1D-F). Together, these findings provide strong evidence that lorcaserin decreases the reinforcing effects of cocaine and methamphetamine, and that tolerance does not develop to these effects of lorcaserin during the course of repeated administration (at least 14 days).

Of the 12 preclinical studies that have evaluated lorcaserin in drug self-administration or reinstatement assays, 11 have reported favorable results across multiple species (rats and rhesus monkeys) and drug classes (nicotine, ethanol, cocaine, and opioids), with a single study reporting that lorcaserin was ineffective at shifting the allocation of behavior away from cocaine in a cocaine versus food choice procedure (Banks & Negus, 2017). Although such a uniformly positive preclinical profile certainly warrants clinical evaluations, a variety of factors, including differences in outcome measures (i.e., decrease drug-taking in preclinical studies versus complete abstinence in clinical studies), make it difficult to predict whether lorcaserin will prove to be as effective at prolonging abstinence in humans as it is at reducing drug self-administration in rats and monkeys. For example, even though preclinical studies have consistently demonstrated that lorcaserin decreases drug intake, the effects have been relatively modest in rats (~30-50% reductions; Levin et al., 2011; Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016; Neelakantan et al., 2017), with the largest doses tested in monkeys (3.2 mg/kg; IG) only reducing cocaine self-administration by 75% (acute) or 50% (repeated) (Collins et al., 2016: Gerak et al., 2016). This profile of activity suggests that still larger doses might be required to achieve clinically relevant outcomes (i.e., sustained abstinence), thereby increasing the likelihood that lorcaserin treatment would be associated with other adverse effects.

4. EVIDENCE FOR 5-HT2C AND 5-HT2A RECEPTOR-MEDIATED EFFECTS OF LORCASERIN

Studies with the 5-HT2C receptor selective antagonist SB 242,084 (Table 1) in rodents suggest that the capacity of lorcaserin to decrease the intravenous self-administration of nicotine, cocaine, and oxycodone is mediated by its actions at 5-HT2C receptors (Higgins et al., 2012; Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016; Neelakantan et al., 2017); however, several lines of evidence suggest that lorcaserin also has actions at 5-HT2A receptors. First, in vitro functional studies suggest that lorcaserin is only modestly (~19-fold) selective for 5-HT2C over 5-HT2A receptors in vitro (Thomsen et al., 2008; also see Table 1), raising the possibility that the doses required to decrease intravenous drug self-administration are large enough to bind to and possibly exert effects at 5-HT2A receptors. Indeed, when evaluated in a sample of recreational polydrug users, doses only slightly larger (20-60 mg) than the maximally approved dose of 10 mg (administered twice daily [BID]) produced feelings of “high” and “bad effects”, as well as perceptual changes that were described by a subset of subjects as “hallucination” and/or feeling “detached” and “spaced out” (Shram et al., 2011). Dose-dependent increases in other adverse effects (e.g., nausea, headache, dizziness, euphoric mood, etc.) were also noted, with most subjects (70-100%) reporting at least one adverse effect after receiving larger doses of lorcaserin (Shram et al., 2011). Although there are no reports of antagonism studies that might confirm the receptor(s) mediating these adverse effects, these effects are likely due to these doses of lorcaserin having agonist actions at 5-HT2A receptors.

Although it is difficult to make direct comparisons of dose across species, evidence suggests that doses of lorcaserin required to decrease drug self-administration in rats and monkeys produce peak plasma levels that exceed the steady state blood levels of ~60 ng/ml observed in humans given the largest approved dose of lorcaserin (10 mg BID) (Arena Pharmaceuticals, 2010, FDA Briefing Document NDA 22529). For instance, in monkeys, acute administration of 3.2 mg/kg (IG) lorcaserin has been reported to produce peak plasma levels of ~80 ng/ml (Collins et al., 2016), whereas in rats the acute sub-cutaneous (SC) administration of 1 mg/kg lorcaserin produced peak blood levels ~230 ng/ml (Higgins et al., 2012). Not only are these plasma levels greater than those achieved by 10 mg lorcaserin (BID) in humans, but evidence from humans (Smith et al., 2009) suggests that twice daily dosing can result in plasma levels of lorcaserin ~30% greater than those achieved during acute dosing conditions (i.e., ~100 ng/ml in monkeys administered 3.2 mg/kg [IG; BID], and ~300 ng/ml in rats administered 1 mg/kg [SC; BID]). Thus, it is reasonable to assume that translating these positive preclinical effects to humans could require doses ~2 to 5-fold greater than what is currently approved for use in humans, well within the range of doses reported to produce adverse effects in humans (Shram et al., 2011).

One way to begin to assess the potential for “off-target” (i.e., non-5-HT2C receptor-mediated) effects is to compare the relative potencies of lorcaserin to decrease drug-taking behavior and to induce behavioral effects mediated by various 5-HT receptor subtypes. For example, Serafine and colleagues (2015) characterized the behavioral profile of lorcaserin in rats and reported it to induce yawning, a 5-HT2C receptor-mediated behavior (e.g., Collins & Eguibar, 2010), over a range of small doses (0.0178-0.1 mg/kg), with no other behaviors noted until forepaw treading, a 5-HT1A receptor-mediated behavior (e.g., Berendsen et al., 1989; Kleven et al., 1997), was observed at doses of 3.2 mg/kg and larger (Figure 2A-C; open circles). Importantly, not only were these effects inhibited by 5-HT2C receptor (yawning) and 5-HT1A receptor (forepaw treading) selective antagonists (Figure 2A and C; closed symbols), but they are consistent with in vitro binding studies (Thomsen et al., 2008) that suggest lorcaserin is highly selective for 5-HT2C over 5-HT1A receptors. Despite the fact that prototypical 5-HT2A receptor-mediated effects, such as head twitch (Vicker et al., 2001), were not observed when lorcaserin was administered alone, previous studies have suggested that agonist actions at 5-HT2C receptors can inhibit the head twitch response in mice (Fantegrossi et al., 2010). Importantly, even though 5-HT2C receptor agonists can attenuate 5-HT2A receptor-mediated head twitch, it is not necessarily the case that 5-HT2C receptor agonists inhibit all 5-HT2A receptor-mediated effects (e.g., hallucination); however, this interaction suggests that 5-HT2A receptor-mediated effects of lorcaserin could be unmasked by combining lorcaserin with a 5-HT2C receptor antagonist. Indeed, when the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist SB 242,084 was administered prior to lorcaserin (Figure 2B; filled circles), the head twitch response emerged at doses of lorcaserin as small as 1 mg/kg; head twitch was not evident when the same doses of lorcaserin were administered alone. Not only is this behavioral profile consistent with lorcaserin having actions at 5-HT2A receptors, but it also suggests that it is only modestly (~18-fold) selective for 5-HT2C over 5-HT2A receptors in vivo, raising the possibility that the adverse effects of lorcaserin (e.g., “bad drug effect”, “hallucination”, etc.) are mediated by its actions at 5-HT2A receptors. Indeed, Serafine and colleagues (2016) provided further support for this notion by demonstrating that the 5-HT2A receptor agonist DOM increased lorcaserin-appropriate responding in rats trained to discriminate a relatively small dose (0.56 mg/kg) of lorcaserin from saline. Thus, even though antagonist studies provide strong evidence that the capacity of lorcaserin to decrease drug self-administration is mediated by its actions at 5-HT2C receptors (Higgins et al., 2012; Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016; Neelakantan et al., 2017), it is important to note that doses of lorcaserin that are minimally effective in decreasing drug self-administration in rats (~0.3-1.25 mg/kg) are ~20 to 30-fold larger than those that produce other 5-HT2C receptor-mediated effects (e.g., yawning), but comparable to those that have been shown to produce 5-HT2A receptor-mediated effects (e.g., head twitch). These data from rats suggest that lorcaserin might have a relatively narrow therapeutic window to treat substance abuse; however, it should be noted that the functional selectivity of lorcaserin for 5-HT2C over 5-HT2A receptors is lower for receptors derived from rats (~3.5-fold) relative to humans (~19-fold; Thomsen et al., 2008), raising the possibility that lorcaserin may have a wider safety margin in humans.

Figure 2.

Acute effects of lorcaserin on directly observable behaviors in male Sprague-Dawley rats. A) Lorcaserin induces yawning over a range of small doses (0.0178-0.56 mg/kg) (open circles); however, this effect is inhibited by pretreatment with the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist SB 242,084 (filled circles); B) lorcaserin fails to induce head twitch (a 5-HT2A receptor-mediated effect) over a wide range of doses (0.1-17.8 mg/kg) (open circles); however, significant increases in head twitch are observed when lorcaserin is administered after pretreatment with the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist SB 242,084 (filled circles); C) lorcaserin induces forepaw treading over a range of large doses (1-32 mg/kg) (open circles), and this effect is inhibited following pretreatment with the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY 100,635 (filled circles); data are expressed as a change from saline. Data were replotted with permission from Serafine et al., 2015.

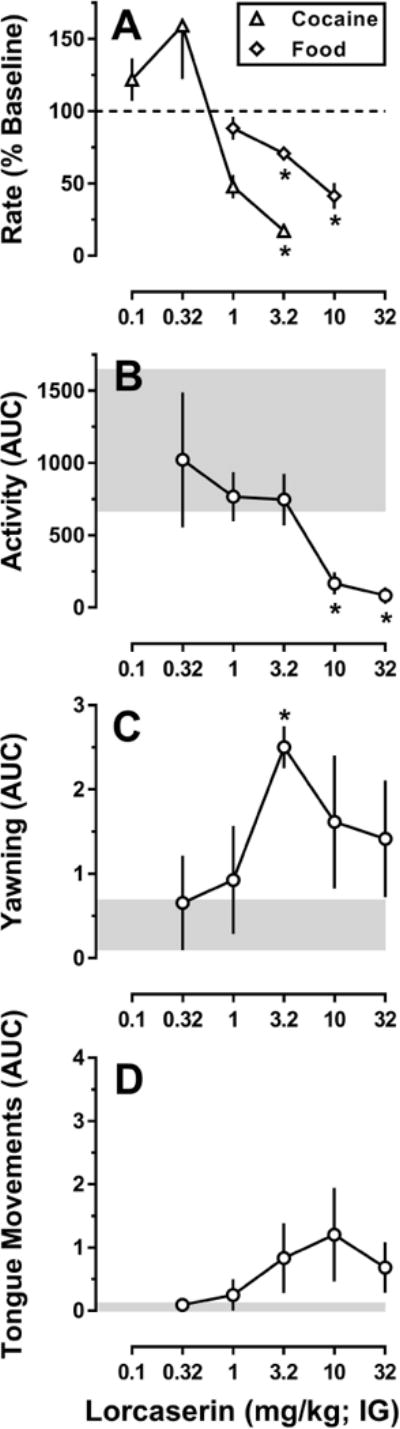

Observational studies in non-human primates support this notion, with lorcaserin-induced yawning (Figure 3C), a 5-HT2C receptor-mediated behavior (e.g., Collins & Eguibar, 2010; Serafine et al., 2015), occurring over the same range of doses that decreased responding for cocaine (Figure 3A), whereas doses ~3 to 5-fold larger were required to disrupt responding for food (Figure 3A), decrease locomotor activity (Figure 3B), and induce abnormal tongue movements (Figure 3D; Collins et al., 2016). Although this profile of activity is consistent with a role for 5-HT2C receptors in decreasing cocaine self-administration, further studies will be required to rule out the possibility that these doses of lorcaserin are acting at other receptors, particularly 5-HT2A receptors.

Figure 3.

Relative potency of acute lorcaserin administration (IG) to alter responding maintained by cocaine or food, locomotor activity, and directly observable behaviors in rhesus monkeys. A) Lorcaserin dose dependently decreases rates of responding maintained by 0.032 mg/kg/infusion cocaine (FR30:TO 180-sec) (open triangles) or food pellets (FR10) (open diamonds), with a minimally effective dose of 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin; B) lorcaserin dose dependently decreases spontaneous locomotor activity with a minimally effective dose of 10 mg/kg lorcaserin; C) lorcaserin dose dependently increases yawning with a minimally effective dose of 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin; D) lorcaserin increases tongue movements over a range of doses; however, none of these effects were significantly different than saline. For panel A, response rate data are expressed as a percent of the rate of responding observed following IG administration of saline (i.e., baseline). For panels B, C, and D the data are expressed as the area under the curve (AUC) for the effects of each dose of lorcaserin over a 4-hr observation period. Data obtained after saline administration are represented by the gray-shaded areas. * p < 0.05; denotes effects that were significantly different from saline, as determined by post hoc Holm–Sidak tests. Data are replotted with permission from Collins et al., 2016.

The putative 5-HT2A receptor agonist effects of lorcaserin have generally been thought to be dose limiting (i.e., something to be avoided), it is possible that agonist actions at 5-HT2A receptors contribute to the effectiveness of lorcaserin to decrease drug self-administration in preclinical studies. For example, recent studies showing that 5-HT2A receptor agonists, such as psilocybin, can prolong abstinence from smoking or alcohol consumption (Garcia-Romeu et al., 2014; Bogenschutz et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2017a; Johnson et al., 2017b) have renewed interest in the development of 5-HT2A receptor agonists as candidate medications for substance abuse. However, because the effectiveness of psilocybin to decrease drug use appears to be linked to its capacity to produce a “mystical” experience (e.g., feelings of unity, sacredness, positive mood, transcendence of space/time, and ineffability), it seems unlikely that the putative 5-HT2A receptor-mediated effects of lorcaserin (e.g., increases in “bad effects”, and reductions in “overall drug liking” and willingness to “take drug again”; Shram et al., 2011) would result in a psilocybin-like effect on drug taking.

5. CLINICAL TRIALS OF LORCASERIN FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Taken together with a growing number of preclinical studies establishing a role for 5-HT2C receptor agonists in modulating reward-related behaviors (Grottick et al., 2000; Fletcher et al., 2004, 2008, 2010; Cunningham et al., 2011; Manvich et al., 2012a, 2012b; Higgins et al., 2013a), mounting evidence suggests that lorcaserin, an FDA-approved 5-HT2C receptor-preferring agonist, could prove useful for treating the abuse of a diverse set of substances including nicotine, ethanol, cocaine, methamphetamine, and opioids. Accordingly, there are currently 13 clinical trials (3 completed and 10 currently recruiting subjects) to evaluate lorcaserin alone, or as an adjuvant to other approved therapies (i.e., nicotine patch, varenicline, naltrexone), for a variety of indications related to the abuse of nicotine (NCT02906644, NCT02044874, NCT02412631), cocaine (NCT03007394, NCT03192995, NCT02680288, NCT02393599, NCT03143543, NCT02537873), opioids (NCT03169816, NCT03143543, NCT03143855), or cannabis (NCT02932215). Although a 3-month randomized trial showed that 10 mg lorcaserin BID can improve rates of abstinence and reduce weight gain associated with smoking cessation (Shanahan et al., 2016), the results of the other clinical trials will be important for determining the clinical utility of lorcaserin for treating substance use disorders more generally.

Regardless of whether lorcaserin proves to be effective at prolonging abstinence from drug use, it is important to remember that it has limited selectivity for 5-HT2C over 5-HT2A receptors, and that doses only slightly larger than those currently approved for use in humans (10 mg, BID) have been shown to produce adverse, “off-target” effects that are likely mediated by 5-HT2A receptors (Shram et al., 2011). Taken together with data from preclinical studies in rodents and non-human primates in which relatively large doses of lorcaserin were required to decrease on-going drug self-administration (or the reinstatement of extinguished responding), it is possible, if not likely, that doses larger than 10 mg (BID) lorcaserin will be required to produce clinically relevant outcomes (i.e., sustained abstinence) thereby increasing the likelihood for 5-HT2A receptor-mediated effects (e.g., hallucination) that could limit the therapeutic potential of lorcaserin to treat substance abuse.

6. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Together with preclinical and clinical evidence that 5-HT2C receptor agonists, such as lorcaserin, are effective at reducing food intake in obese individuals, the positive results from preclinical studies with lorcaserin and other 5-HT2C receptor agonists provide strong support for a more general role of 5-HT2C receptors in regulating food- and drug-motivated behaviors. Although it is too early to tell whether the preclinical effects of lorcaserin to decrease the reinforcing and relapse-related effects of a variety of drugs of abuse will translate to clinical success, the efforts already underway to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of lorcaserin will not only provide valuable information but also serve as a good first test of the 5-HT2C receptor hypothesis in humans. Future efforts should be directed towards developing novel agonists with greater selectivity for 5-HT2C over 5-HT2A receptors, such as CP-809101 (~1500-fold selective for 5-HT2C over 5-HT2A receptors; Siukiak et al., 2007), which appear to have a similar profile of activity in preclinical models of substance abuse with a lower incidence of “side effects” (Higgins et al., 2013b). Although additional studies are needed, lorcaserin represents a promising and important first step towards the development of a new class of pharmacotherapies that have the potential to dramatically improve the treatment of especially challenging clinical conditions, such as substance abuse, for which there are few (if any) effective therapies.

Highlights.

Lorcaserin is a 5-HT2C receptor agonist approved for treating obesity in humans.

Lorcaserin also decreases drug self-administration in preclinical studies.

Lorcaserin also might be useful in treating drug abuse.

Large doses of lorcaserin produce hallucinations in humans and head-twitch in rats.

Actions at 5-HT2A receptors might limit the therapeutic utility of lorcaserin.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants U01 DA034992, K05 DA017918, T32 DA031115, and R01 DA05018] and by the Welch Foundation [Grant AQ-0039]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors thank Eli Desarno, Marlisa Jacobs, Nicole Garcia, Mark Garza, Steven Garza, Taylor Martinez, Marissa McCarthy, Chris Robinson, and Crystal Taylor for their technical contributions towards the completion of these studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations: Food and Drug Administration (FDA), dopamine transporter (DAT), serotonin transporter (SERT), norepinephrine transporter (NET), serotonin (5-HT), gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), twice daily (BID), intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS); intra-gastric (IG), fixed ratio (FR), progressive ratio (PR), sub-cutaneous (SC), time out (TO), extinction (EXT), baseline (BL), area under the curve (AUC)

References

- Arena Pharmaceuticals. Briefing document: NDA 22–529. 2010 lorcaserin hydrochloride (APD356) [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Negus SS. Repeated 7-Day treatment with the 5-HT2C agonist lorcaserin or the 5-HT2A antagonist pimavanserin alone or in combination fails to reduce cocaine vs food choice in male rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:1082–1092. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.259. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen HH, Jenck F, Broekkamp CL. Selective activation of 5HT1A receptors induces lower lip retraction in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;33:821–827. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PC, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:289–299. doi: 10.1177/0269881114565144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881114565144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs SA, Hall BJ, Wells C, Slade S, Jaskowski P, Morrison M, Rezvani AH, Rose JE, Levin ED. Dextromethorphan interactions with histaminergic and serotonergic treatments to reduce nicotine self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2016;142:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.12.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Gerak LR, Javors MA, France CP. Lorcaserin reduces the discriminative stimulus and reinforcing effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;356:85–95. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.228833. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.115.228833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Eguibar JR. Neurophamacology of yawning. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2010;28:90–106. doi: 10.1159/000307085. https://doi.org/10.1159/000307085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins V, Rose JE, Levin ED. IV nicotine self-administration in rats using a consummatory operant licking response: sensitivity to serotonergic, glutaminergic and histaminergic drugs. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;54:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.06.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KA, Fox RG, Anastasio NC, Bubar MJ, Stutz SJ, Moeller FG, Gilbertson SR, Rosenzweig-Lipson S. Selective serotonin 5-HT(2C) receptor activation suppresses the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine and sucrose but differentially affects the incentive-salience value of cocaine- vs. sucrose-associated cues. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.04.034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.04.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis C, O’Brien C. Glutamatergic agents for cocaine dependence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:328–345. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Stewart J. Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1981;75:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00432175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Ullrich T, Rice KC, Woods JH, Winger G. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) and its stereoisomers as reinforcers in rhesus monkeys: serotonergic involvement. Psychopharmacology. 2002;161:356–364. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1021-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-002-1021-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Simoneau J, Cohen MS, Zimmerman SM, Henson CM, Rice KC, Woods JH. Interaction of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors in R(−)-2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine-elicited head twitch behavior in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:728–734. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.172247. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.110.172247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Grottick AJ, Higgins GA. Differential effects of the 5-HT(2A) receptor antagonist M100907 and the 5-HT(2C) receptor antagonist SB242084 on cocaine-induced locomotor activity, cocaine self-administration and cocaine-induced reinstatement of responding. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:576–586. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00342-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00342-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Chintoh AF, Sinyard J, Higgins GA. Injection of the 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro60-0175 into the ventral tegmental area reduces cocaine-induced locomotor activity and cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:308–318. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300319. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Rizos Z, Sinyard J, Tampakeras M, Higgins GA. The 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro60-0175 reduces cocaine self-administration and reinstatement induced by the stressor yohimbine, and contextual cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1402–1412. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301509. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Sinyard J, Higgins GA. Genetic and pharmacological evidence that 5-HT2C receptor activation, but not inhibition, affects motivation to feed under a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;97:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.07.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Rizos Z, Noble K, Soko AD, Silenieks LB, Lê AD, Higgins GA. Effects of the 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro60-0175 and the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100907 on nicotine self-administration and reinstatement. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:2288–2298. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2014;7:157–164. doi: 10.2174/1874473708666150107121331. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerak LR, Collins GT, France CP. Effects of lorcaserin on cocaine and methamphetamine self-administration and reinstatement of responding previously maintained by cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;359:383–391. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.236307. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.116.236307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Shearer J, Merrill J, Negus SS. Agonist-like, replacement pharmacotherapy for stimulant abuse and dependence. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1439–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grottick AJ, Fletcher PJ, Higgins GA. Studies to investigate the role of 5-HT(2C) receptors on cocaine- and food-maintained behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:1183–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich I, Tamir H, Arango V, Dwork AJ, Mann JJ, Schmauss C. Altered editing of serotonin 2C receptor pre-mRNA in the prefrontal cortex of depressed suicide victims. Neuron. 2002;34:349–356. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00660-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon J, Hoyer D. Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2008;195:198–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey-Lewis C, Li Z, Higgins GA, Fletcher PJ. The 5-HT(2C) receptor agonist lorcaserin reduces cocaine self-administration, reinstatement of cocaine-seeking and cocaine induced locomotor activity. Neuropharmacology. 2016;101:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Silenieks LB, Rossmann A, Rizos Z, Noble K, Soko AD, Fletcher PJ. The 5-HT2C receptor agonist lorcaserin reduces nicotine self-administration, discrimination, and reinstatement: relationship to feeding behavior and impulse control. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1177–1191. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.303. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Sellers EM, Fletcher PJ. From obesity to substance abuse: therapeutic opportunities for 5-HT2C receptor agonists. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013a;34:560–570. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.08.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Silenieks LB, Lau W, de Lannoy IA, Lee DK, Izhakova J, Coen K, Le AD, Fletcher PJ. Evaluation of chemically diverse 5-HT2C receptor agonists on behaviours motivated by food and nicotine and on side effect profiles. Psychopharmacology. 2013b;226:475–490. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2919-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-012-2919-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Byrd LD. Serotonergic modulation of the behavioral effects of cocaine in the squirrel monkey. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1551–1559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Cunningham KA. Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor interactions with dopamine function: implications for therapeutics in cocaine use disorder. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67:176–197. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.009514. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.114.009514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson JD, Setola V, Roth BL, Merryman WD. Serotonin receptors and heart valve disease–it was meant 2B. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;132:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.03.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017a;43:55–60. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Johnson PS, Griffiths RR. An online survey of tobacco smoking cessation associated with naturalistic psychedelic use. J Psychopharmacol. 2017b;31:841–850. doi: 10.1177/0269881116684335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116684335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett GA, Curzon G. Potencies of antagonists indicate that 5-HT1C receptors mediate 1-3(chlorophenyl)piperazine-induced hypophagia. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:2016–2020. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett GA, Wood MD, Bright F, Trail B, Riley G, Holland V, Avenell KY, Stean T, Upton N, Bromidge S, Forbes IT, Brown AM, Middlemiss DN, Blackburn TP. SB 242084, a selective and brain penetrant 5-HT2C receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:609–20. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleven MS, Assié MB, Koek W. Pharmacological characterization of in vivo properties of putative mixed 5-HT1A agonist/5-HT(2A/2C) antagonist anxiolytics. II. Drug discrimination and behavioral observation studies in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:747–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacosta S, Roberts DC. MDL 72222, ketanserin, and methysergide pretreatments fail to alter breaking points on a progressive ratio schedule reinforced by intravenous cocaine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;44:161–165. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launay JM, Hervé P, Peoc’h K, Tournois C, Callebert J, Nebigil CG, Etienne N, Drouet L, Humbert M, Simonneau G, Maroteaux L. Function of the serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine 2B receptor in pulmonary hypertension. Nat Med. 2002;8:1129–1135. doi: 10.1038/nm764. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Johnson JE, Slade S, Wells C, Cauley M, Petro A, Rose JE. Lorcaserin, a 5-HT2C agonist, decreases nicotine self-administration in female rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:890–896. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.183525. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.111.183525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvich DF, Kimmel HL, Howell LL. Effects of serotonin 2C receptor agonists on the behavioral and neurochemical effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012a;341:424–434. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.186981. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.111.186981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvich DF, Kimmel HL, Cooper DA, Howell LL. The serotonin 2C receptor antagonist SB 242084 exhibits abuse-related effects typical of stimulants in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012b;342:761–769. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.195156. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.112.195156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK. Preclinical evaluation of the effects of buprenorphine, naltrexone and desipramine on cocaine self-administration. NIDA Res Monogr. 1990;105:189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane KS, Winschel J, Schmidt KT, Stewart LM, Rose SJ, Cheng K, Rice KC, Howell LL. Serotonin 2A receptors differentially contribute to abuse-related effects of cocaine and cocaine-induced nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopamine overflow in nonhuman primates. J Neurosci. 2013;33:13367–13374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1437-13.2013. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1437-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelakantan H, Holliday ED, Fox RG, Stutz SJ, Comer SD, Haney M, Anastasio NC, Moeller FG, Cunningham KA. Lorcaserin suppresses oxycodone self-administration and relapse vulnerability in rats. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8:1065–1073. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00413. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Henningfield J. Agonist medications for the treatment of cocaine use disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:1815–1825. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.322. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AH, Grundt P, Nader MA. Dopamine D3 receptor partial agonists and antagonists as potential drug abuse therapeutic agents. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3663–3679. doi: 10.1021/jm040190e. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm040190e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nic Dhonnchadha BA, Fox RG, Stutz SJ, Rice KC, Cunningham KA. Blockade of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor suppresses cue-evoked reinstatement of cocaineseeking behavior in a rat self-administration model. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:382–396. doi: 10.1037/a0014592. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor EC, Chapman K, Butler P, Mead AN. The predictive validity of the rat self-administration model for abuse liability. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:912–938. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockros LA, Pentkowski NS, Swinford SE, Neisewander JL. Blockade of 5-HT2A receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex attenuates reinstatement of cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2011;213:307–320. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2071-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-2071-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter RH, Benwell KR, Lamb H, Malcolm CS, Allen NH, Revell DF, Adams DR, Sheardown MJ. Functional characterization of agonists at recombinant human 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors in CHO-K1 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:13–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702751. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0702751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani AH, Cauley MC, Levin ED. Lorcaserin, a selective 5-HT(2C) receptor agonist, decreases alcohol intake in female alcohol preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;125:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.07.017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science. 1987;237:1219–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.2820058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Brebner K. GABA modulation of cocaine self-administration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;909:145–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH. Serotonergic drugs and valvular heart disease. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8:317–329. doi: 10.1517/14740330902931524. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740330902931524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Prisinzano TE, Newman AH. Dopamine transport inhibitors based on GBR12909 and benztropine as potential medications to treat cocaine addiction. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüedi-Bettschen D, Spealman RD, Platt DM. Attenuation of cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking in squirrel monkeys by direct and indirect activation of 5-HT2C receptors. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:2959–2968. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3932-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-015-3932-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S, Foote J, Aronsen D, Bukholt N, Highgate Q, Van de Wetering R, Webster J. Serotonin antagonists fail to alter MDMA self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2016;148:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.06.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Rice KC, France CP. Directly observable behavioral effects of lorcaserin in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;355:381–385. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.228148. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.115.228148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Rice KC, France CP. Characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of lorcaserin in rats. J Exp Anal Behav. 2016;106:107–16. doi: 10.1002/jeab.222. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan WR, Rose JE, Glicklich A, Stubbe S, Sanchez-Kam M. Lorcaserin for smoking cessation and associated weight gain: a randomized 12-week clinical trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw301. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw301 pii: ntw301 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shram MJ, Schoedel KA, Bartlett C, Shazer RL, Anderson CM, Sellers EM. Evaluation of the abuse potential of lorcaserin, a serotonin 2C (5-HT2C) receptor agonist, n recreational polydrug users. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:683–692. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.20. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2011.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuciak JA, Chapin DS, McCarthy SA, Guanowsky V, Brown J, Chiang P, Marala R, Patterson T, Seymour PA, Swick A, Iredale PA. CP-809,101, a selective 5-HT2C agonist, shows activity in animal models of antipsychotic activity. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Prosser WA, Donahue DJ, Morgan ME, Anderson CM, Shanahan WR, APD356-004 Study Group Lorcaserin (APD356), a selective 5-HT(2C) agonist, reduces body weight in obese men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:494–503. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.537. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Weissman NJ, Anderson CM, Sanchez M, Chuang E, Stubbe S, Bays H, Shanahan WR, Behavioral Modification and Lorcaserin for Overweight and Obesity anagement (BLOOM) Study Group Multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of lorcaserin for weight management. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:245–256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909809. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0909809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Newman AH, Katz JL. Discovery of drugs to treat cocaine dependence: behavioral and neurochemical effects of atypical dopamine transport inhibitors. Adv Pharmacol. 2009;57:253–289. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)57007-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-3589(08)57007-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tecott LH, Sun LM, Akana SF, Strack AM, Lowenstein DH, Dallman MF, Julius D. Eating disorder and epilepsy in mice lacking 5-HT2c serotonin receptors. Nature. 1995;74:542–546. doi: 10.1038/374542a0. https://doi.org/10.1038/374542a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen WJ, Grottick AJ, Menzaghi F, Reyes-Saldana H, Espitia S, Yuskin D, Whelan K, Martin M, Morgan M, Chen W, Al-Shamma H, Smith B, Chalmers D, Behan D. Lorcaserin, a novel selective human 5-hydroxytryptamine2C agonist: in vitro and in vivo pharmacological characterization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:577–587. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133348. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.107.133348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2016. United Nations publication; 2016. Sales No. E.16.XI.7. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers SP, Easton N, Malcolm CS, Allen NH, Porter RH, Bickerdike MJ, Kennett GA. Modulation of 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated head-twitch behaviour in the rat by 5-HT(2C) receptor agonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;69:643–652. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeb FD, Higgins GA, Fletcher PJ. The serotonin 2C receptor agonist lorcaserin attenuates intracranial self-stimulation and blocks the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2015;6:1231–1240. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]