Abstract

Radiometals are becoming increasingly accessible and are utilized frequently in the design of radiotracers for imaging and therapy. Nuclear properties ranging from the emission of γ-ray and β+-particles (imaging) to Auger electron, β− and α-particles (therapy) in combination with long half-lives are ideally matched with the relatively long biological half-life of monoclonal antibodies in vivo. Radiometal labelling of antibodies requires the incorporation of a metal chelate onto the monoclonal antibody. This chelate must coordinate the metal under mild conditions required for the handling of antibodies, as well as provide high kinetic, thermodynamic and metabolic stability once the metal ion is coordinated in order to prevent in vivo release of the radionuclide before the target site is reached. Herein, we review the role of different radiometals that have found applications the design of radiolabelled antibodies for imaging and radioimmunotherapy. Each radionuclide is described with regard to its nuclear synthesis, coordinative preference, and radiolabelling properties with commonly used and novel chelates, as well as examples of their preclinical and clinical applications. An overview of recent trends in antibody-based radiopharmaceuticals is provided to spur continued development of the chemistry and application of radiometals for imaging and therapy.

Keywords: Radiometals, chelates, coordination chemistry, immuno-PET, radioimmunotherapy

Graphical Abstract

We review the role of different radiometals that have found applications for the radiolabelling of antibodies for imaging and radioimmunotherapy. An overview of their nuclear synthesis, coordinative preference, and radiolabelling properties with commonly used and novel chelates, as well as examples of their preclinical and clinical applications is provided.

Introduction

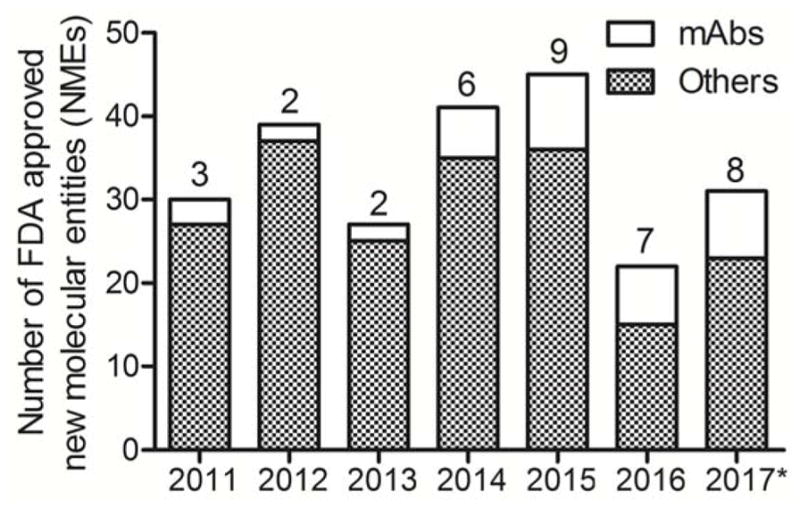

In the pharmaceutical industry, biological products (biologics) and related biosimilar compounds represent one of the fastest growth sectors. In 2016, the size of the biologics market was estimated to be ~$200 billion USD. Recent forecasts predict continued growth at around 10% per annum with the market reaching ~$480 billion USD by 2024. Biologics include recombinant hormones and proteins, as well as cellular- and gene-based therapies, but the majority of this growth is driven by new vaccines and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). Monoclonal antibodies or antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent the single most important branch of biologics.1 Between 2011 and August 2017, the United States Federal Drug Administration (US-FDA) approved a total of 235 New Molecular Entities (NMEs), of which 37 were either mAbs or ADCs for therapy (Figure 1). This growing trend is supported by historical data which suggest that biologics, and mAbs in particular, have received higher approval rates than conventional small-molecule drugs.2 With prescription costs for mAb-based treatments estimated to be around 22-times more than small-molecule therapies, and profit margins often over 40%, it is easy to see the commercial attraction of biologics. However, this success is partially offset by the longer time frames required from initial clinical trials to full approval, more stringent manufacturing regulations, and the associated increase in costs. Recent changes to US legislation, implemented as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, are also helping to create an abbreviated licensure pathway for NMEs that are demonstrated to be “biosimilar” to, or “interchangeable” with, an FDA-licensed biological product. This new legal framework will speed-up the discovery and clinical translation of mAb-based agents.

Figure 1.

Stacked bar chart showing the total number of US-FDA approved New Molecular Entities from 2011 until August 2017 with a breakdown showing the contribution from mAb-based agents and other drugs. * Data available until 08/2017.

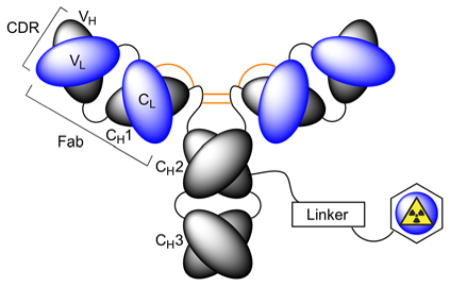

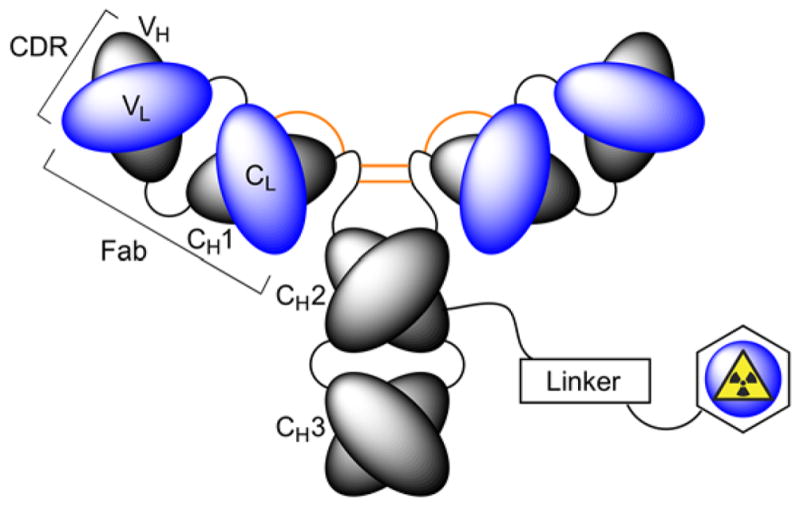

In nuclear medicine, desirable biochemical properties including high target affinity, specificity and selectivity, pre-optimised pharmacokinetics, and relative ease of selection using various library technologies mean that antibody-based radiotracers are attractive platforms for developing diagnostic imaging and radioimmunotherapy (RIT) agents.3–6 Nevertheless, production and validation of radiolabelled mAbs for use as immuno-single photon emission computed tomography (immuno-SPECT), immuno-positron emission tomography (immuno-PET) or RIT agents is non-trivial.3 Synthesis of radiolabelled mAbs requires chemical reactions on the protein (Figure 2). Functionalisation usually involves post-translational modification of amino-acid side chains (particularly peptide bond formation using the primary amine group of lysine residues), derivatisation of cysteine sulfhydryl groups, or site-specific labelling of glycans using chemical and/or enzymatic methods.7,8 More recent protein engineering routes have also exploited site-specific enzymatic ligation with prominent methods including transglutaminase derivatisation, sortase coupling and formylglycine reactions to produce a range of ADCs.7–9 While the chemical nature of the linker group plays an important role in determining the metabolic stability and pharmacokinetics of a radiolabelled mAb, an equally important decision revolves around the choice of the radiometal ion and the chelation chemistry used to produce thermodynamically and kinetically stable radiometal ion complexes.10 In this review, we discuss the chemical requirements for chelation of various radiometal ions and highlight selected applications of radiometal chemistry in the development of radiotracers for immuno-PET, immune-SPECT and RIT.11

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of a radiolabelled mAb involving chemical modification of the protein using covalent bond formation to a radiometal binding chelate via a linker group.

1. Radionuclides for antibody imaging and therapy

In this issue of the Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals, Engle and co-workers present an overview of the emerging radionuclides for use in combination with mAbs for diagnostic and RIT applications. Pertinent physical decay characteristics of 11 radiometal ions, and for comparison three different iodine radionuclides are presented in Table 1.12 When selecting a radionuclide for labelling antibodies or antibody-related constructs, the most crucial decision is to ensure that the physical half-life of the radionuclide is a reasonable match to the expected biological half-life of the radiotracer in vivo.10 For example, 68Ga (t1/2 = 67.7 min.) is an excellent radionuclide for producing PET radiotracers based on small-molecules and peptides but would be an inappropriate choice for developing immuno-PET radiotracers based on full-sized mAbs (molecular weight ~150 kDa). Experience has found that mAbs reach optimum target (usually tumour) uptake and present maximal tumour-to-background contrast ratios in mouse models at around 24 – 96 h post-administration. Hence, in this pharmacokinetic situation, 68Ga is likely to undergo complete decay before the biodistribution of a radiolabelled mAb reaches the optimum imaging window. Notably, in humans the pharmacokinetic profiles of radiolabelled mAbs are often slower than in rodents, with optimum target accumulation and image contrast achieved at time points beyond 72 h post-administration of the radiotracer. Such prolonged circulation times necessitate the use of radionuclides that have physical half-lives ranging from ca. 10 hours to several days. For immuno-PET imaging, 64Cu, 86Y, 89Zr and 124I are the most commonly used radionuclides, whereas for immuno-SPECT, 67Ga, 99mTc, 111In, 123I and 177Lu have been the radionuclides of choice. The majority of radiolabelled mAbs for applications in RIT use the beta-emitting radionuclides 90Y, 131I, and 177Lu. Other radionuclides of note for potential RIT applications include the dual-decay mode of 64Cu (branching ratio of 38.5% beta-decay to the daughter nuclide 65Zn), 67Cu13 and the alpha emitter 225Ac.14,15

Table 1.

Physical decay characteristics of various radionuclides that have potential applications in diagnostic imaging and radioimmunotherapy with antibody-based radiopharmaceuticals.

| Radionuclide | Half-life, t1/2 | Decay mode (% branching ratio) | Production route(s) | GS-GS Q-value (keV) | Particle end-point energy / keV | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64Cu | 12.701 h | ε+β+ (61.5%) β+ (17.60%) β− (38.5%) |

64Ni(p,n)64Cu | 1675.03 (64Ni) 579.4 (64Zn) |

β+ 653.03 β− 579.4 |

Immuno-PET and RIT |

| 67Cu | 61.83 h | β− (100%) |

68Zn(p,2p)67Cu 70Zn(p,α)67Cu 67Zn(n,p)67Cu 68Zn(γ,p)67Cu |

561.7 | β− 561.7 | RIT (Immuno-SPECT) |

| 67Ga | 3.2617 d | ε (100%) |

natZn(p,x)67Ga 68Zn(p,2n)67Ga |

1000.8 | Auger and CE | Immuno-SPECT and RIT |

| 86Y | 14.74 h | ε+β+ (100%) β+ (31.9%) |

86Sr(p,n)86Y | 5240 | β+ 3141 | Immuno-PET |

| 89Zr | 78.41 h | ε+β+ (100%) β+ (22.74%) |

89Y(p,n)89Zr | 2833 | β+ 902 | Immuno-PET |

| 90Y | 64.00 h | β− (100%) | 90Sr/90Y | 2280.1 | β− 2280.1 | RIT |

| 99mTc | 6.01 h | β− (0.0037%) IT (99.9963%) |

99Mo/99mTc | Excited state (parent) level: 142.68 | β− 435.9 | Immuno-SPECT |

| 111In | 2.8047 d | ε (100%) |

111Cd(p,n)111m,gIn 112Cd(p,2n)111m,gIn |

862 | Auger and CE | Immuno-SPECT and RIT |

| 123I | 13.2234 h | ε (100%) |

124Xe(p,2n)123Cs/123Xe/123I 124Xe (p,pn)123I 123Te(p,n)123I |

1228.6 | Auger and CE | RIT (Immuno-SPECT) |

| 124I | 4.1760 d | ε+β+ (100%) β+ (22.7%) |

124Te(p,n)124I | 3159.6 | β+ 2137.6 | Immuno-PET |

| 131I | 8.0252 d | β− (100%) | 130Te(n, γ)131Te/131I | 970.8 | β− 806.9 Auger and CE |

RIT |

| 177Lu | 6.647 d | β− (100%) |

176Lu(n, γ)177Lu 176Yb(n, γ)177Yb/177Lu |

498.3 | β− 498.3 Auger and CE |

RIT (Immuno-SPECT) |

| 213Bi | 45.59 m | α(2.20%) β− (97.80%) |

225Ac/213Bi | β− 1423 α 5988 |

β− 1423 α 5875 Auger and CE |

RIT |

| 225Ac | 10.0 d | α(100%) | 229Th/225Ra/225Ac | 5935.1 | α 5830 Auger and CE |

RIT |

2. Copper radiolabelled antibodies

Copper has a range of radionuclides with varying decay characteristics that are suitable for applications in both nuclear imaging and molecularly targeted radionuclide therapy.16 PET imaging radionuclides of copper include 60Cu (t1/2 = 23.7 min.), 61Cu (t1/2 = 3.333 h), 62Cu (t1/2 = 9.67 min.) but with the possible exception of 61Cu for use in radiolabelling small peptides, proteins and antibody-based fragments, the most suitable radionuclide for combination with immuno-PET is 64Cu.17 In addition to PET imaging, 64Cu also shows potential for therapeutic applications via separate decay involving beta-particle emission. However, 67Cu (t1/2 = 61.83 h; β– = 100%) with a maximum linear energy transfer of 561.7 keV is one of the most promising radionuclides for potential development of 67Cu-mAbs for RIT.18

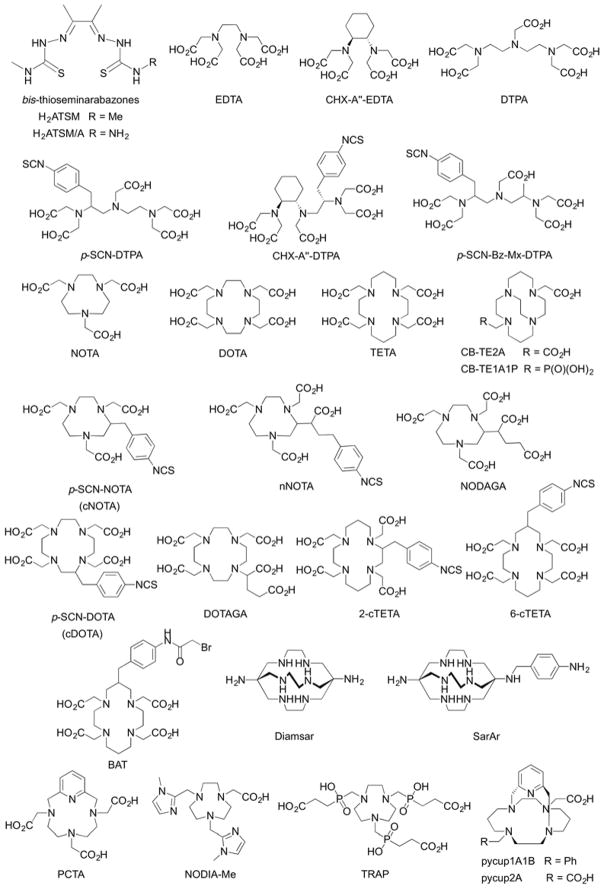

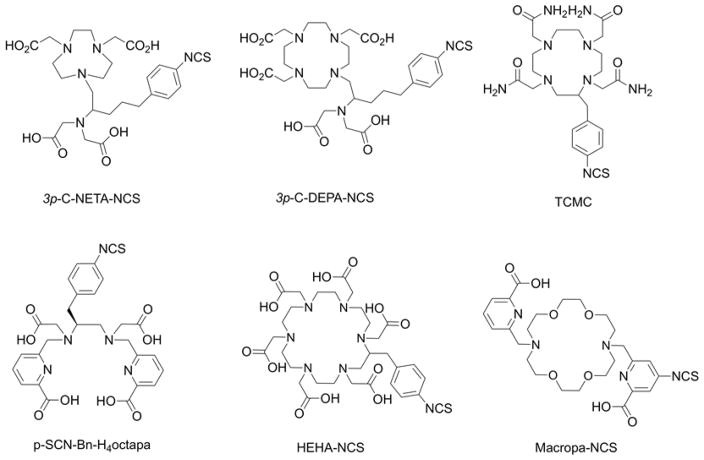

While the radiochemical landscape of copper radionuclides presents opportunities for developing imaging and therapeutic agents, controlling the chemistry of copper ions in vivo remains a formidable challenge.19,20 Copper chemistry in oxygenated, aqueous conditions is dominated by the Cu2+ cation. Cu2+ ions have a d9 electronic configuration which induces large Jahn-Teller distortion in the first coordination sphere and the additional crystal field stabilisation favours complexes with a 4-coorindate, square planar geometry. The charge density of Cu2+(aq.) ions (ionic radius = 0.80 Å)21 lies intermediate between hard class A ions and softer class B metal ions. This property means that Cu2+ ions favour coordination with chelating ligands that present a mixed donor set with both small, hard donors like N and O, and larger, soft S donors. For this reason, some of the most successful chelates for coordinating Cu2+ ions have been developed around bis-thiosemicarbazonato-based ligand systems that offer dative covalent bond formation via N2S2 or N2SO donor atoms sets (Figure 3).22 Although tetra-coordinate, square planar complexes with a fully occupied d(z2)2 orbital stabilise Cu2+ ions thermodynamically, ligands like H2ATSM, and the asymmetric bifunctional version H2ATSM/A, have two faces of the central metal cation open to solvent.23 Solvent exposed sites in the first coordination sphere leave complexes like CuATSM susceptible to degradation via nucleophilic attack, which can decrease their overall kinetic/metabolic stability in vivo. In the case of copper-based radiotracers, loss of the metal ion from the radiopharmaceutical leads to higher accumulation of radioactivity in background tissues such as the liver, spleen and kidneys. For immuno-PET and immuno-SPECT agents, such instability can complicate analysis and quantification by reducing target specificity and decreasing image contrast. For RIT, off-target accumulation of radioactivity causes a potential problem in terms of dosimetry with the need to avoid radiation dose to background organs to minimise potential side-effects. Therefore, when developing copper-based mAbs, it is of paramount importance to minimise demetallation/transchelation in vivo.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of selected chelates that have been employed for complexation of various radiometal ions including those of copper, gallium, indium, yttrium, lutetium, actinium and beyond.

Another aspect of copper chemistry that must be taken into account when selecting a suitable ligand is the fact that Cu2+ ions undergo facile one-electron reduction to their corresponding Cu+ species. While square planar Cu2+ complexes are thermodynamically stable due to high crystal field splitting forces, Cu+ complexes prefer a tetrahedral geometry and are often far less stable with lower formation constants (log β). Reduced Cu+ complexes are also kinetically labile and normally undergo rapid ligand exchange, leading to demetallation and potential loss of the copper ion in vivo to competing ligands such human serum albumin, ceruloplasmin and other copper-binding proteins. Single-crystal X-ray structures supported by Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations have shown that tetra-coordinate Cu2+ complexes comprising asymmetric donor atom sets like N2S2 bis-thiosemicarbazonato ligands induce a twist distortion in the square planar geometry.23 While structural distortion induces a slight increase in thermodynamic stability of complexes like CuATSM/A, the twisted geometry lies intermediate between true square planar Cu2+ complexes and a tetrahedral geometry favoured for reduced Cu+ complexes. Hence, geometric distortion facilitates metal-centred reduction of Cu2+ complexes to give Cu+ species that rapidly demetallate in vivo due to their lower thermodynamic, kinetic and metabolic stability. For this reason, N2S2 bis-thiosemicarbazonato ligands are typically not employed in the design of long-circulating copper-radiolabelled mAbs. Instead, the majority of copper-radiolabelled mAbs concentrate on stabilising the Cu2+ ion, and have been developed around aza-macrocyclic-based chelates like NOTA, DOTA and TETA (Figure 3). Other Cu2+ chelates incorporate varying combinations of macrocyclic N-donors with other donor groups such as carboxylates, phosphates or heteroaromatic rings such as derivatised pyridines or imidazoles etc.

To best of our knowledge, only two different chelates, BAT and DOTA, have been used in the development of 64/67Cu-radiolabelled mAbs for imaging and RIT in human trials. In a pioneering Phase I/II clinical trial, Philpott et al. investigated the distribution and specificity of a 64Cu-labelled murine mAb, [64Cu]-BAT-2IT-1A3, in 36 patients with suspected advanced primary or metastatic colorectal cancer.24 Imaging was compared with compared [18F]-FDG and the study found that [64Cu]-BAT-2IT-1A3 was more specific for detecting colorectal tumours than [18F]-FDG which showed false positive indications in patients with inflammatory lesions. The sensitivity of [64Cu]-BAT-2IT-1A3 was found to be 71% per lesion and 86% per patient. The investigation also found that immuno-PET imaging with [64Cu]-BAT-2IT-1A3 offered diagnostic improvements over previously developed radioimmunoscintigraphy imaging using [111In]-HBED-1A325 (63% per lesion and 76% per patient). Critically, follow-up studies found no adverse side-effects from 64Cu-mAb administration. However, it was noted that in about 25% of patients, increased titres of human anti-mouse antibody (HAMA) were found. This immune response toward an administered mAb-based radiopharmaceutical can be minimised/avoided by the use of chimeric or fully humanised mAbs. Subsequent pre-clinical studies by Connett et al.26 showed the potential of both 64Cu and 67Cu-radiolabelled BAT-2IT-1A3 for RIT. Small GW39 tumours (~0.2 g) showed 82% and 93% remission in tumour size when treating with 2.0 mCi of 64Cu- or 0.4 mCi of 67Cu-BAT-2IT-1A3, respectively. Interestingly, larger tumours (~0.6 g) only showed growth inhibition but not regression, even when treating with higher doses of radioactivity. These data highlight an important limitation of using mAb-based drugs that often fail to penetrate fully into the core of larger solid tumours.

In the late 1990s, DeNardo and co-workers reported preclinical27 studies and clinical translation13,28,29 of the radiolabelled murine mAb, 67Cu-BAT-2IT-Lym-1, for RIT in patients with Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). In one study, O’Donnell et al.28 measured the dosimetry and pharmacokinetics of 67Cu-BAT-2IT-Lym-1 in 12 NHL patients with stage III or IV disease that had failed to respond to standard therapy. Patients received up to 4 separate doses of 67Cu-RIT at 4 week intervals with administered activities between 0.93 – 2.22 GBq/m2/dose. The trial found that chemotherapy-resistant patients had a combined partial and complete response rate of 58% (7/12 patients). Radiation dosimetry measurements confirmed specificity of radiotracer uptake in tumours which led to disease lesions receiving the highest mean radiation dose (2.35±0.97 Gy/GBq). Measurements also found favourable radiotracer distribution with tumour-to-background organ ratios against marrow lung, kidney and liver of 28:1, 7.4:1, 5.3:1 and 2.6:1, respectively. In a follow-up study, Mirick et al.13 performed detailed analysis of the radiochemical stability of 67Cu-BAT-2IT-Lym-1. Transfer of 67Cu to ceruloplasmin was observed in all patients with an average of 2.8±1.5% of the initial dose being lost to ceruloplasmin in the liver. The release rate of 67Cu from 67Cu-ceruloplasmin in the liver to the blood was 0.9±0.4 %ID/day during the first 3 days post-radiotracer administration. The researchers noted that loss of 67Cu ions to endogenous proteins led to a biphasic clearance rate.

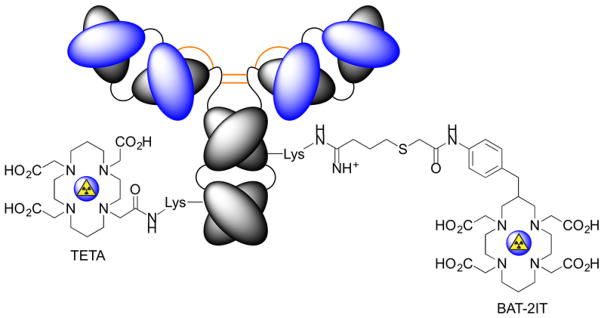

In efforts to increase the metabolic stability of 64/67Cu-radiolabelled mAbs, Lewis et al.30 compared 64Cu-TETA-1A3 versus 64Cu-BAT-2IT-1A3 (Figure 4). Head-to-head experiments showed that conjugation of the TETA chelate to the mAb via amide bond formation led to favourable serum stability, biodistribution, immunoreactivity and dosimetry properties. Alongside earlier work,31 these data demonstrate the importance of developing new chelating systems to increase the stability of Cu-based radiotracers in vivo.

Figure 4.

Chemical conjugation of TETA and BAT-2IT to antibodies coupling to the ε-NH2 group of lysine residues.

Recent clinical studies using 64Cu-mAbs have tended to employ the DOTA chelate coupled to the mAb via amide bond formation. Clinical trials worldwide have reported the efficacy of using 64Cu-DOTA-trastuzumab to measure expression of the human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2/neu) in breast cancer patients.32–34 In addition, 64Cu-labelled cetuximab for imaging epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) has been studied extensive in preclinical work with experiments comparing the performance of different chelates including DOTA,35,36 CB-TE1A1P, CB-TE1K1P in combination with either tradition amide bond coupling or ‘Copper-free Click’ methods for rapid bioconjugation.37 As efforts gather pace to improve access to 67Cu,18 identification of new chelates, linkers and radiolabelling methods to produce 64/67Cu-mAbs is essential.

3. Zirconium radiolabelled antibodies

Over the last two decades, 89Zr (t1/2 = 78.41 h; β+ = 22.74%) has emerged as the most important radionuclide for immuno-PET.4 Elsewhere in this issue of Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals, Viola-Villegas and co-workers present a detailed overview of progress made in the use of 89Zr-radiolabelled mAbs for clinical imaging. The follow section focuses on the radiochemistry and coordination chemistry of 89Zr4+ ions. The half-life of just over 3 days matches well with the extended circulation times of mAbs in the human body which facilitates accurate measurements of antibody pharmacokinetics at time points beyond 1 week after radiotracer administration. The chemistry and radiochemistry of 89Zr offers a number of technological advantages over other radionuclides such as 64Cu. 89Zr is produced via low energy (ca. 13 – 15 MeV) proton beam irradiation of commercially available 89Y solid metal foils.38 The 89Y target material has a natural isotopic abundance of 100%, which unlike 64Cu that requires recycling of isotopically enriched 64Ni electroplated targets, makes production of 89Zr comparatively cheap. Extraction methods are optimised and fully automatable yielding either 89Zr-tetraoxalate ([89Zr(C2O4)4]4−) or 89Zr-chloride in high chemical and radiochemical purity, and high specific activity (470–1195 Ci/mmol).

The aqueous phase chemistry of zirconium is limited to the group oxidation state of 4+ with a d0 electronic configuration. The thermodynamic stability of Zr4+ complexes is dominated by electrostatic interactions with no contribution from crystal field stabilisation. The very high charge density of Zr4+(aq.) ions (ionic radius = 0.85 Å)21 induces significant bond polarisation in the first coordination sphere and the dative bonds have strong ‘covalent character’. The very low solubility product of Zr(OH)4 (log Ksp = 56.94±0.32)39 means that Zr4+ species have a strong tendency to hydrolyse and form colloidal species in aquo. Avoiding precipitation of Zr-oxo species requires the use of metal binding chelates that form exceptionally stable complexes with high-valent metal ions. For this reason, most of the work using 89Zr-mAbs has employed the hexadentate, tris-hydroxamic acid chelate, desferrioxamine B (DFO). The formation constant of Zr-DFO has yet to be determined but experience has found that excess Fe3+ ions do not transmetallate with the preformed ZrDFO complex on a time scale appropriate for immuno-PET (Holland unpublished data). This observation suggests that either the ZrDFO complex is kinetically stable toward transmetallation with Fe3+ ions, and/or that the formation constant of ZrDFO is possibly higher than the reported thermodynamic stability of FeDFO (log β = 30.6).40

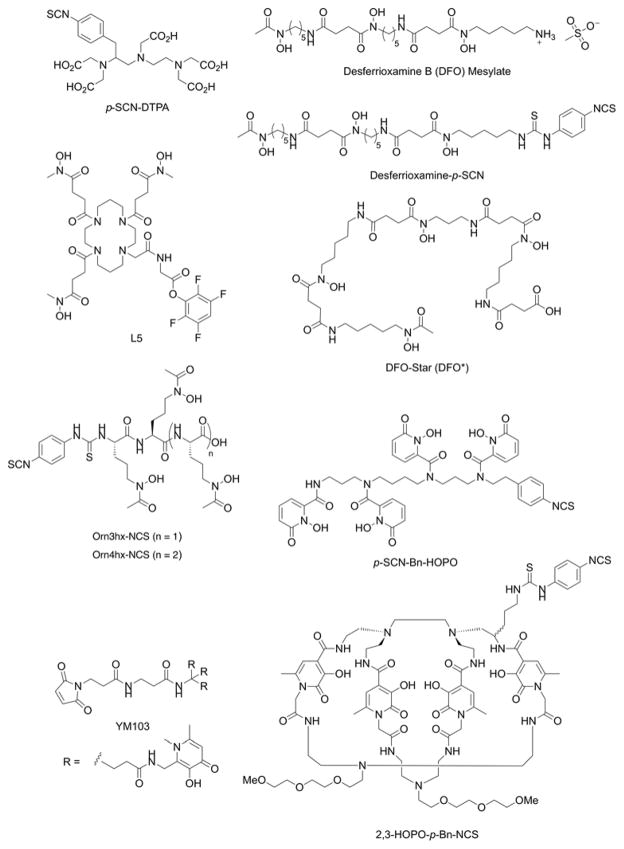

It is notable that although DFO is an exceptionally powerful chelate for coordination of Zr4+ ions, zirconium has the ability to accommodate between 6 and 8 donor atoms in the first coordination. DFT calculations have indicated that DFO fails to fully saturate the first coordination sphere of Zr4+ ions and the ligand is quite strained.41,42 One or two vacant coordination sites are potentially occupied by labile water molecules or anions like chloride. Additional experiments using 89Zr-immuno-PET in rodent models have found elevated levels of activity accumulating in the bone over time. Interestingly, bone activity is typically higher when investigating tumour models that show positive expression of the target antigen than in models where tumour accumulation occurs via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR).41,43–45 These data point toward a specific intratumoural metabolism that leads to recirculation of unidentified Zr4+ species that sequester in the bone. Other studies have shown that [ZrDFO]+ is excreted rapidly via a renal clearance mechanism yet other species including a putative ‘89Zr-chloride’ in phosphate buffered saline, and [89Zr(C2O4)4]4− accumulate in liver and bone, respectively.38,46 Collectively, data suggest that 89Zr species with overall anionic charge have a higher propensity to sequester in bone. As previously mentioned for the 64Cu work, further studies are required to elucidate the nature of the radioactive metabolites that recirculate in vivo after release from tumours and potentially other background organs like the liver. We note that similar bone sequestration of 89Zr radioactivity has not been reported in human trials. Nevertheless, these preclinical data, combined with the fact that DFO does not fully satisfy the coordination requirements Zr4+ ions, have prompted recent efforts in the design and synthesis of alternative chelate systems for this radionuclide.47 A selection of recent bifunctional chelates that have been developed as potential alternatives to the ‘gold standard’ DFO chelates are presented in Figure 5.47–53

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of selected bifunctional chelates that have been developed for derivatisation of proteins and complexation of 89Zr4+ ions.

Detailed DFT calculations explored the mechanism of ligand substitution between oxalate and hydroxamate ligands bound to Zr4+ ions.42 This computational study revealed a comprehensive set of ‘design criteria’ that can aid the synthesis of new chelates for selective, high affinity coordination of Zr4+ ions. New ligands should aim to incorporate hard, class A donor atoms in a ligand geometry that is pre-organised for coordination to Zr4+ ions. Since Zr4+ ions can accommodate between 6- to 8- donor atoms in the first coordination sphere, new chelates should aim to maximise thermodynamic and kinetic stability. Whilst increasing the denticity of a chelate has the general effect of increasing the thermodynamic and kinetic stability of a metal complex due to an increased chelate effect, there is no fixed rule that dictates 7- or 8-coordinate complexes are more stable that 6-coordinate complexes. Rather, the relative thermodynamic stability between 6-, 7- and 8-coorindate complexes is a balance between the generally increased stabilisation acquired through coordination of an extra donor atom versus increased repulsive forces generated from increased steric crowding in the first coordination sphere and potentially increased strain induced in the ligand backbone. Furthermore, larger metal ion complexes with 8-coordinate geometries are likely to be more susceptible toward ligand exchange mediated by solvent (water) molecules. For maximum thermodynamic stabilisation of Zr4+ ions, ligand scaffolds should be carefully designed to increase the acidity of the donor atoms. This will potentially increase the degree of “covalent-character” bonding between the ligand and 89Zr4+ ions. To achieve this, donor atoms should be part of strongly acidic groups. Suitable functional groups that have been used in the design of successful Zr4+ chelates include carboxylic acids, phosphates, hydroxamic acids, phenols, catechols, and hydroxypyridinonates (Figure 5).

Desferrioxamine B is a natural product produced by bacteria and acts as a siderophore, extracting Fen+ ions from highly insoluble iron oxides (the log Ksp (Fe(OH)3 lies between 10−37 and 10−44 depending on the conditions).54 Extracting iron from soil requires very powerful chelates which can pose a potential problem for radiochemistry with 89Zr4+ ions. While [Zr(DFO)]+ is stable with respect to transmetallation by Fe3+ ions, care must be taken to ensure that no iron contaminants are present in any of the solutions used for 89Zr4+ extraction or radiolabelling. Experience has found that trace amounts of Fe3+ ions act as efficient ‘poisons’ toward 89Zr radiochemistry. Since the majority of new chelates designed for coordination of 89Zr4+ ions are based on, or inspired by, the structures of siderophores, working with high-purity metal ion free solutions is essential to ensure that radiolabelling proceeds efficiently, and generates products with high radiochemical purity and effective specific activity. In spite of these challenges, efficient protocols have been reported for producing many 89Zr-DFO-mAbs.43,55 We note that although several bifunctional chelates have been produced and claimed to be superior in terms of radiochemical stability toward transchelation of Zr4+ ions, it is yet to be seen if any of these new ligands will emerge as a genuine competitor to DFO. In the clinical setting, DFO has a number of strong advantages that present a very high barrier for any alternative chelate to cross. For instance, DFO is a US-FDA approved drug, it is readily available and cheap, has good solubility properties (unlike many new chelates), and chemical methods for attaching DFO to mAbs are highly reproducibly, efficient and now practiced as routine in many radiochemistry facilities. As clinical trials using 89Zr-DFO-mAbs accelerate, and generally image quality from reported clinical trials is considered excellent with no loss of radiometal to the bone, these positive experiences will make many physicians reluctant to venture into uncharted waters without obvious need or benefit. In addition, the costs of generating essential toxicological studies of a new chelate prior to clinical translation may prove prohibitive for most second-generation chelates. The question that must be addressed by any new radiotracer (or here chelate) is, how much better must a new tool be to cause the Nuclear Medicine community to shift from a well-established, reliable and trusted technology?

While the ability to image mAb distribution over the course of several weeks can be considered an advantage, the major limitations of 89Zr-mAbs are the comparatively poor dosimetry profile and the practical challenges of managing patients who receive a 89Zr radiotracer injection and remain radioactive for extended periods of time. Long circulation times with limited excretion mean that 89Zr-mAb radiotracer doses are limited to ~185 MBq56–58 with typical doses of, for example, 89Zr-DFO-trastuzumab for imaging HER2/neu expression in breast cancer patients around 37 MBq/patient. As an initial tool to validate the usefulness of a new biomarker, 89Zr-mAbs remain an excellent choice. However, as alternative radiotracers based on small-molecules are developed to image the same targets, for example 68Ga-urea-based Glu-NH-C(O)-NH-Lys compounds for PET imaging of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) agents, practical considerations are likely to dictate the long-term future of 89Zr-mAbs.

4. Gallium-67 radiolabelled antibodies

Gallium-67 radiolabelled mAbs were amongst some of the first antibody-based radiotracer tools developed for radioimmunoscintigraphy and immuno-SPECT.59 The radiochemical properties of 67Ga (t1/2 = 3.26 d; ε = 100%), with intense Auger electron emissions and various γ-rays emitted in the range 8 – 887 keV make this radionuclide suitable for both imaging and RIT with mAbs. Similar to 89Zr, 67Ga3+ exist in the group oxidation state with no redox chemistry. The thermodynamic stability of Ga3+ complexes is dominated by electrostatic interactions with a strong preference for hexadentate chelates proffering hard, class A donor atoms. In addition, the high charge density of Ga3+ ions (ionic radius = 0.62 Å)21 leads to a high propensity of Ga complexes to hydrolyse in aqueous solution, potentially forming Ga-colloidal species of uncertain chemical composition. Stabilising Ga3+ ions against rapid hydrolysis and formation of either gallium tetrahydroxide anions (Ga(OH)4−) or Ga-colloids requires careful control of the reaction buffer composition, ionic strength and pH, and the use of chelates that form Ga complexes with very high formation constants. Chelates of choice for Ga3+ radionuclides include bifunctional derivatives of DFO, EDTA and various aza-macrocycles primarily based on the structures of NOTA and DOTA (Figures 3 and 5). Indeed, Koizuma et al. reported efficient radiolabelling of 67Ga-DFO-mAbs in 1988. Interestingly, they also tested the stability of different coupling strategies and found that the use of glutaraldehyde coupling led to high non-specific uptake in liver and spleen. In contrast, 67Ga-DFO-mAbs linked via thioether bonds (maleimido chemistry) displayed the highest tumour-to-liver ratios, and radiotracers produced using disulphide bridges were unstable, with activity cleared rapidly from circulation. Nowadays, alternative methods for mAb coupling and different chelates for Ga3+ ion coordination are available but DFO remains a competitive choice.60 With a prevailing shift toward immuno-PET, development of 67Ga-mAbs has stagnated in recent years. Nevertheless, as research efforts aimed at delivering an Auger-emitting radionuclide to the cell nucleus intensify, 67Ga has potential to see a resurgence in interest. A recent article by Othman et al. reassessed the therapeutic potential of 67Ga and concluded that on a per cell basis, 67Ga causes as much damage as 111In to plasmid DNA.61

5. Indium-111 radiolabelled antibodies

Since the 1980s, 111In-radiolabelled mAbs have been developed as tools for radioimmunoscintigraphy, immuno-SPECT and for RIT. The radionuclide 111In (t1/2 = 2.80 d; ε = 100%) decays with intense low energy Auger electron emission (2.72 keV, 100%) and also emits a number of γ-rays whose energy and intensity (171 keV [90.7%]; 245 keV [94.1%]) are ideally suited for high resolution SPECT imaging and targeted RIT.

In the following examples of 111In-mAbs, DTPA was used as the chelate for coordination of the 111In3+ ion. Indium lies underneath gallium in group 13 (group 3A) of the Periodic Table. As such, the chemistry of In3+ and Ga3+ ions are quite similar. One notable difference is that In3+ ions have a larger ionic radius (0.80 Å)21 and can accommodate additional donor atoms in the first coordination sphere. In this regard, the coordination requirements of 111In3+ lie between Ga3+ and Zr4+ ions, and for this reason, DTPA (which offers up to nine, class A, hard donor atoms) remains the primary chelate used for 111In3+ coordination. To the best of our knowledge, little work has been reported on the development of alternative chelates for specific coordination of 111In3+ ions. However, as discussed for 67Ga, the resurgence of interest in targeted RIT using Auger emitters is likely to stimulate radiochemists to revisit the coordination chemistry and radiochemistry of 111In.

Indeed, early clinical studies reported by Ryan et al.62 found that imaging was able to detect breast lesions in breast cancer patients infused with varying doses of different human IgM monoclonal antibodies 111In-YBB-190, 111In-YBB-209 or 111In-YBB-088. However, antigen expression levels and mAb dose were critical factors in determining the success of diagnostic imaging with 111In-mAbs.

One of the earliest radiolabelled mAbs to receive US-FDA approval (in 1996) for imaging was 111In-capromab pendetide (111In-7E11; ProstaScint®). 111In-capromab pendetide is a mouse mAb that recognizes a specific intracellular epitope of prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and can be used for immuno-SPECT imaging of prostate cancer soft tissue metastases. Unfortunately, targeting an intracellular epitope led to sub-optimal performance of this radiotracer in clinical diagnosis of prostate cancer with fairly low sensitivity for viable tumour lesions (62% for lymph node metastases; 50% for prostate bed recurrence). Furthermore, 111In-capromab pendetide was not able to identify prostate cancer lesions in bone which is the most common site of metastatic disease in this patient population. Subsequent preclinical and clinical studies using 89Zr-DFO-J591 to image an extracellular epitope of PSMA mean that 89Zr-immuno-PET has largely superseded the need for 111In-ProstScint scans. Despite limitations, 111In-capromab pendetide remains available on the market.

Several other 111In-mAbs have previously received US-FDA approval include 111In-satumomab pendetide (OncoScint®) for imaging TAG-72, a tumour-associated antigen found on ~95% of colorectal carcinomas and 100% of ovarian carcinomas; 111In-imiciromab-pentetate (MyoScint®), a murine mAb Fab-fragment directed against human cardiac myosin and formerly used for cardiac imaging; 111In-igovomab (Indimacis-125®), a mouse F(ab′)2 fragment for imaging carcinoma antigen 125 (CA-125) in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. However, each of these 111In-radiotracers has subsequently been withdrawn.2

6. Technetium-99m radiolabelled antibodies

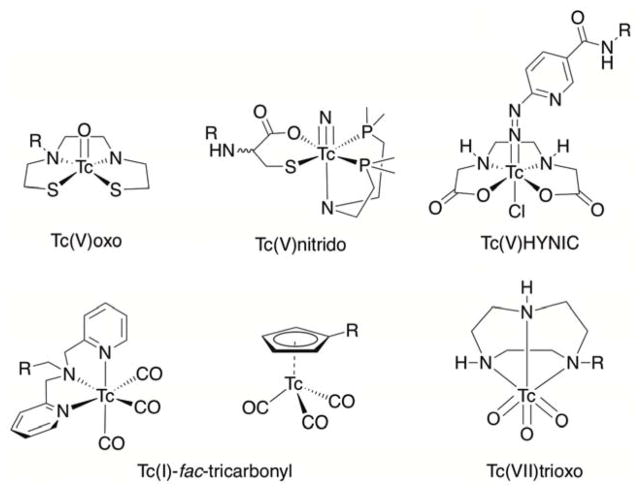

Technetium-99m (t1/2 = 6.01 h; IT = 100%) is the most common radionuclide used to develop SPECT radiotracers.63 In contrast to many other radionuclides described here, the chemistry of 99mTc is highly diverse. Technetium lies in group 7B of the Periodic Table, underneath manganese, and as such, exhibits a rich redox chemistry. 99mTc species in a wide range of oxidation states from –1 to +7 have been reported. Variable oxidation states mean that Tc complexes are potentially redox active, implying that 99mTc-complexes must be designed to be thermodynamically and/or kinetically stabile toward redox reactions in vivo. The majority of radiotracers have been developed around 99mTc5+ and 99mTc+ ions. A unique feature of 99mTc radiochemistry is the concept of utilising different ‘99mTc-cores’ with the three most common being {99mTc=O}, {99mTcO3} and {99mTc(CO)3} (Figure 6).63

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of 99mTc chelates that incorporate different ‘99mTc-cores’.

During the mid-1990s to mid-2000s, a number of 99mTc-mAbs received market approval.2 For example, 99mTc-nofetumomab merpentan (Verluma®) is a mouse mAb Fab-fragment attached to a merpentan chelate and used for imaging the pan-carcinoma glycoprotein antigen EpCAM and/or CD20/MS4A1 in cancers of the lung, gastrointestinal tract, breast, ovary, pancreas, cervix, kidney and bladder. Verluma® was approved in 1996 but withdrawn in 1999. 99mTc-arcitumomab (CEA-Scan®) is a mouse Fab′ fragment developed by Immunomedics to target the Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) cell-adhesion proteins which are biomarkers on various cancers including colorectal tumours. CEA-Scan® was approved in 1996 but withdrawn in 2005. 99mTc-sulesomab (LeukoScan®) received approval in 1997 and is a mouse Fab′ fragment that targets granulocyte cell antigen NCA-90 and is used for imaging infections and inflammations in patients with suspected osteomyelitis. LeukoScan® is also being investigated in the evaluation of soft tissue infections.64 99mTc-votumumab (HumaSPECT®) is a human monoclonal antibody for detection of 3-fucosyl-N-acetyl-lactosamine (CD15) expression in colorectal tumours. Although HumaSPECT® received approval in 1998, it was withdrawn in 2004 without being made available on the market. Finally, 99mTc-fanolesomab (NeutroSpec®) is a mouse mAb developed to target CD15 and received approval in 2004 for diagnosis of appendicitis. However, in December 2005 the US-FDA issued an alert and NeutroSpec® marketing was voluntarily suspended due to reports of serious and life-threatening cardiopulmonary events that followed immediately after NeutroSpec® administration. Two deaths were reported and further patients experiences serious complications including cardiac arrest, hypoxia, dyspnea and hypertension. While these adverse reactions were most likely due to a reaction to the antibody-component and not the radionuclide, it offers a lesson that, as with chemotherapeutic drugs, full preclinical characterisation of radiotracers is crucial before translation to the clinic.

7. Iodine radiolabelled antibodies

Although not radiometals, iodine radionuclides remain among the most frequently utilised therapeutic isotopes in the clinic. The radionuclide of primary interest is 131I due to its dual emission capabilities. 131I (t1/2 = 8.1 d) emits β– particles (average energy of 192 keV with a range of 0.8 mm in tissue) as well as a concomitant γ-emission (364 keV) suitable for SPECT imaging.65 131I is a reactor-produced isotope, conveniently accessible from 235U fission products.66 However, 123I and 125I have also become of interest due to their potential for either imaging or Auger therapy applications, respectively. The photon energy of 125I is considered too low for optimal imaging, especially for quantitative imaging, and its half-life is undesirably long. Thus, 125I is typically used for in vitro applications and radioactive binding assays.67 124I (t1/2 = 4.2 days) has a relatively low ratio of disintegration resulting in positrons (about 23%), and a complex decay scheme which includes high-energy gamma emissions (highest about 1.7 MeV). It is typically produced by using enriched 124Te via the 124Te(d,2n)124I reaction or in recent years, the 124Te(p,n)124I reaction.68

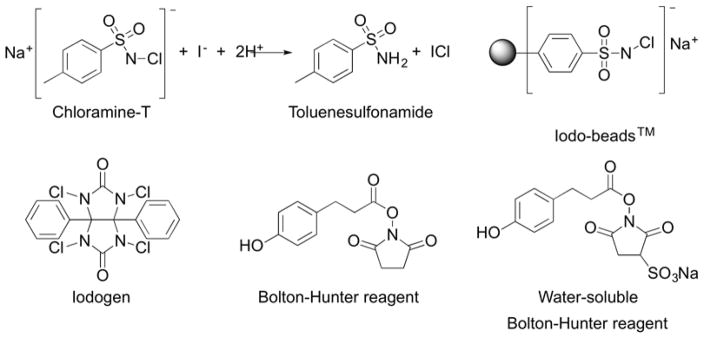

In contrast to radiolabelling with metal ions, incorporation of iodine radionuclides requires formation of covalent bonds. Typically, radioiodine is introduced using mild oxidative reagents that minimise potential chemical degradation of mAbs. Chloramine-T (N-chloro-p-toluene sulfonamide) is an aromatic oxidising agent commonly used for this purpose, but requires close monitoring and quenching of the reaction before excessive mAb oxidation occurs (Figure 7).69 The use of solid-support chloramine-T provides a milder radiolabelling alternative, allowing for filtration workups as a way to rapidly remove the oxidant.70 Another commonly used oxidizing agent employed is iodogen (1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3α,6α-diphenylglycoluril).71 Other methods involve radioiodination of an activated-ester small molecule (N-succinimidyl 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate; Bolton-Hunter reagent) with chloramine-T, followed by mAb conjugation in a secondary step.72

Figure 7.

Chemical structures of various reagents used for oxidative radiolabelling of proteins with iodine radionuclides.

[131I]NaI-mediated treatment of malignant thyroid disorders has represented a mainstay of RIT in the clinic. Recently, 131I-mAbs are becoming of greater interest for targeted cancer therapy. 131I-tositumomab (Bexxar®) is the earliest representative of this compound class. 131I-tositumomab is used to treat certain types of NHL.73 Investigations have also sought define the role of 131I-tositumomab RIT in treating Hodgkin’s lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma,74 and multiple myeloma.75 Based on the promising outcomes in clinical studies, 131I-tositumomab was approved by the FDA for clinical practice in patients with lymphoma. 131I-Lym-1 (Oncolym®) is an 131I-radiolabelled mAb in Phase III clinical trials for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.76 Cotara® is a genetically engineered chimeric human/mouse mAb that binds to the DNA-histone H1 complex, targeting the necrotic core of solid tumours.77 Phase II clinical trials on patients with astrocytoma, brain gliobastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have shown promising results.78 Similarly, the treatment was also found to be successful in lung cancer patients via intratumoral injections.79

Until recently, iodine-124 was not considered to be an attractive isotope for medical applications owing to its complex radioactive decay scheme, which includes several high-energy γ-rays. Limited availability of this radionuclide has also impeded its clinical application. Among clinically assessed 124I-radiotracers, sodium [124I]-iodide is potentially useful for diagnosis and dosimetry in thyroid disease and [124I]-M-iodobenzylguanidine ([124I]-MIBG) has shown promise for cardiovascular imaging as well as dosimetry of malignant diseases such as neuroblastoma, paraganglioma, pheochromocytoma, and carcinoids.80 A number of monoclonal antibodies have been labelled with 124I and imaged successfully in mouse models.81,82 As with several other radionuclides, interest in 124I-mAbs has waned in light of the success of 89Zr-mAbs in preclinical and clinical settings.

8. Yttrium radiolabelled antibodies

90Y is a widely used radiometal for β− therapy. With a half-life of 2.67 days, it decays via β− emission (100%) with a maximum β-particle energy of 2.288 MeV, providing a greater penetration range in vivo than many other β− emitting nuclides.12,83,90Y may be produced using various nuclear reactions. Irradiation of 89Y in a nuclear reactor produces 90Y, however, this route generates an 90Y product with low specific activity that is inseparable from the target material. No-carrier added 90Y can be obtained by separation of 90Y from 90Sr (t1/2 = 28.5 y). Currently, the separation of 90Y is carried out at production sites, and the long half-life of 90Sr could enables manufacture of a generator system comparable to the 99Mo generator for 99mTc. 90Sr is one of the most abundant fission product radionuclides in spent nuclear fuel as it is generated in high yield.84 The high β− energy renders 90Y suitable for treatment of larger, poorly vascularized tumours (approximate β− range of ~12 mm in addition to extended therapeutic range through the “crossfire effect”). More recently, in addition to accessibility of 90Y as a therapeutic isotope, the PET isotope 86Y has emerged as the imaging congener. Currently, primary limitations of use of 86Y clinically are its non-ideal emission characteristics: β+ emissions (2.019, 2.335 MeV) are sub-optimal for imaging due to their high energy leading to decreased image resolution, and poor radiation dosimetry profile arising from high-energy γ–ray emissions (1.077, 1.153, 1.854, 1.921 MeV).85

Y3+ has an ionic radius of 1.02 Å, an absolute electronegativity of 41.2 eV and a hardness of 20.6 eV.86 It ranks among the hardest trivalent ions, exhibiting a strong preference for oxygen and nitrogen donors. Most frequently used chelates for coordination of 86Y/90Y are DOTA87 and CHX-A′′-DTPA88 (Figure 3). Main issues identified with these established ligand systems include slow complexation kinetics at room temperature (DOTA), and/or decreased stability in vivo (DTPA-derivatives).89 To leverage the enhanced kinetic stability of macrocycles and rapid chelation of acyclic systems, Kang et al. have synthesised the bimodal ligands 3p-C-NETA and 3p-C-DEPA (Figure 8) that possess both macrocyclic and acyclic moieties for cooperative metal ion binding. Radiolabelling of these chelates also shows favourable radiochemical yields under mild conditions (room temperature, pH 5.5, 60 min).90 However, only 3p-C-NETA exhibited sufficiently high kinetic stability in plasma challenge experiments. Price et al. evaluated the acyclic bifunctional chelator p-NCS-Bn-octapa-NCS (Figure 8) in comparison with CHX-A′′-DTPA and found that the 90Y-octapa complex exhibited increased plasma stability while maintaining equivalent in vivo performance when conjugated to trastuzumab.91

Figure 8.

Chemical structures of selected chelates that have been employed for complexation of yttrium, lutetium, bismuth, lead and actinium.

The 64-hour half-life and therapy-avid, γ-emission-free nuclear properties have contributed to the clinical success of 90Y in recent years. Ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®) is an FDA-approved 90Y-radiolabelled mAb that combines DTPA linked to ibritumomab, allowing for the targeted irradiation with β-particles in B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.92 A number of new 90Y-labelled mAbs and antibody fragments are currently being assessed for efficacy in clinical trials. 90Y-labelled basiliximab and daclizumab93 for Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as 90Y-labelled microbeads (under the trade names TheraSphere and SIR-Spheres) have obtained FDA approval in 1999 and 2002 for the treatment of non-resectable liver cancer and other applications of radioembolization.94 CD22-targeting 90Y-labelled epratuzumab is currently evaluated in a Phase III trial for the treatment of lymphoma, leukaemia and some immune diseases.95 Work by Salako and co-workers investigating 90Y-BAT-Lym1 in comparison with the 131I and 67Cu-labeled analogue showed decreased efficacy when compared with Lym1 labelled with other therapeutic isotopes.96 Beyond mAb-based agents, 90Y-labelled DOTATOC (somatostatin-conjugate) is also under clinical investigation for the treatment of larger neuroendocrine tumours.97

9. Lutetium-177 radiolabelled antibodies

177Lu (t1/2 = 6.6 days) is a mixed mode β− and γ–ray emitting radionuclide. It decays with emission of β− particles of 176 (12%), 384 (9%), and 497 keV (79%) as well as γ–rays with energies of 208 (11%) and 113 (6.6%) keV rendering this isotope suitable for SPECT imaging and RIT.83 177Lu is typically obtained using reactors by neutron irradiation of 176Lu to afford 177Lu in high yields,98 satisfactory specific activities. However, reactor production yields both the desired 177gLu and the excited state 177mLu as a radionuclidic impurity. 177Lu can also be produced by neutron activation of enriched 176Yb to afford 177Yb (1.9 h half-life), which then decays to 177Lu.99 This synthesis produces higher specific activities and a no-carrier added product, which more desirable for the labelling and in vivo imaging of low-abundance biological targets. The β− emission of 177Lu has an approximate range of 2 mm in vivo, ideal for irradiation of smaller tumours and metastases.

As the element with the greatest number of protons of the lanthanide series, Lu3+ experiences the strongest Lanthanide contraction of ionic radius, ranging from 0.98 Å (coordination number 8) or 1.03 Å (coordination number 9). Lu3+ can be considered a hard Lewis acid with an absolute electronegativity of 33.1 eV and a hardness of 12 eV.86 Depending on the steric crowding of the coordinating chelate, Lu3+ ions commonly form complexes of coordination number 8 or 9. Both cyclic and acyclic chelators have been utilised for this metal ion, specifically DTPA, CHX-DTPA and DOTA.100,101 The slow rate of complexation of DOTA-based ligands with 177Lu becomes a significant disadvantage for preparation of DOTA-based radiopharmaceuticals. For this reason, heating becomes essential in most cases in order to increase the complexation rate Generally, heating at 95 °C for 25–30 min is performed in order to achieve near quantitative radiolabelling yields for the preparation of 177Lu–DOTA-conjugated somatostatin analogues. DOTA–affibodies have been radiolabelled with 177Lu under heating at lower temperature (60 °C) to obtain high-efficiency labelling. Whole antibodies are typically labelled either at room temperature or 37 °C, in order to not jeopardise the integrity of the protein. Typically, this results in less than quantitative radiochemical labelling yields for 177Lu-mAbs or the need to employ reaction times of 1 hour or longer to achieve quantitative complexation of the radionuclide. Once DOTA-type complexes are formed, they exhibit high kinetic and thermodynamic stability, with no significant dechelation reported in vivo, even after long circulation times typical for mAbs. The chelates 3p-C-NETA and 3p-C-DEPA (Figure 8) as synthesized by Kang et al.90 and evaluated with 90Y (vide supra) have also shown promise, with near-quantitative 177Lu labelling yields under mild conditions (room temperature, pH5.5, 60 min). The trastuzumab conjugate of 3p-C-NETA showed high in vivo stability, high tumour uptake and low accumulation in off-target organs. Similarly, trastuzumab conjugates with the acyclic octadentate chelator p-SCN-Bn-octapa (Figure 8) can be labelled with 177Lu at room temperature within 15 minutes.102 This is in contrast with the corresponding DOTA conjugate, which requires 37 °C and extended reaction times (60 min.) to achieve 85% radiochemical yield. Both of these trastuzumab conjugates exhibited identical behaviour in vivo. Octapa-derivatives represent a ligand class that provides an attractive alternative to ‘gold standard’ DOTA derivatives due to their improved radiolabelling characteristics.

The extent of preclinical studies has been reviewed by Banerjee et al.103 In terms of clinical studies, 177Lu has witnessed increasing use. The 6.6 day half-life is suitable for use with both peptides and mAbs as targeting vectors. The long half-life is also suitable for access to 177Lu-therapy in hospitals that do not have access to reactor or cyclotron facilities. The non-quantitative radiolabelling yields of 177Lu with mAb conjugates due to sub-optimal radiolabelling protocols to is one potential reason that has limited a more wide-spread adoption of 177Lu-mAbs in the clinic. Beyond mAb-based agents, 177Lu-DOTATOC/DOTATE has been found to be highly effective for the treatment of neuroendocrine tumours and is currently under regulatory review,104,105 while the imaging-only analogue 68Ga-DOTATE (NETSPOT®) obtained FDA approval in 2016.

10. Lead-212 radiolabelled antibodies

212Pb is produced by the decay chain originating from 232U (228Th decay chain) and can be obtained from a generator made from 224Ac or 224Ra. 212Pb (t1/2 = 10.6 h) is a β-emitter (100%, 570 keV), but is primarily of interest as the parent nuclide of the α-emitting short-lived 212Bi (t1/2 = 60.6 min) and 212Po (t1/2 = 0.3 μs) with deposited energies of 21.1% from the 6.2 MeV 212Bi α-particle emission and 67.3% from the 8.9 MeV 212Po α-particle emission.106 212Pb/212Bi is considered an in vivo generator system.107 212Pb itself can be obtained by way of the 224Ra/212Pb generator. However, the short half-life of 224Ra (t1/2 = 3.7 d) requires frequent replacement in a clinical setting, similar to the 99Mo/99mTc generator system.108 The original generator system was developed in 1989, but in recent years, rekindled interest in α-therapy has resulted in commercial availability.

Pb2+ is a post-transition group 14 metal with ionic radius of 1.29 Å, an electronegativity of 23.5 eV and an absolute hardness of 8.5 eV while Bi3+ is a group 15 metal with an ionic radius of 117 ppm and an absolute hardness of 10.0 eV.86 The chelation chemistry of 212Pb faces the challenge of having to conform to the coordinative preferences of not just Pb2+ but also Bi3+. An additional challenge is posed by the emission of Auger electrons and high recoil energy upon decay to 213Bi which can result in significant radiochemical degradation to the conjugated biomolecule. Initial studies using DOTA conjugates indicated loss of 212Pb from the bioconjugate and thus enhanced radiotoxicity.109 TCMC (Figure 8), a tetramide analogue of DOTA was developed and found to exhibit enhanced kinetic stability with both Pb2+ and Bi3+. The bifunctional, backbone-functionalised version of TCMC has been successfully utilised for conjugation to mAbs and subsequent preclinical and clinical application.110

Prominent early preclinical studies with 212Pb/212Bi include treatment of EL-4 ascites and more contemporarily successful peptide-based metastatic melanoma treatment.111 A study on treatment of breast cancer xenografts with trastuzumab-linked 212Pb-TCMC showed highly promising outcome, providing the basis for human trials.112 A Phase I trial of 212Pb-TCMC-trastuzumab for treatment of HER2-overexpressing cancers has recently been completed.

11. Bismuth-213 radiolabelled antibodies

213Bi is a short-lived isotope (t1/2 = 45.6 min) and decays by α emission (2%, 5.8 MeV) followed by two β emissions, or β emission (98%) followed by an α emission (8.4 MeV) and subsequent β emission to stable 209Bi. In addition, a 440 keV (26%) photon can be utilised for dosimetry via imaging. 213Bi can be obtained from 225Ac as part of the 225Ac/213Bi generator.113 A clinically-used generator has been developed and is commercially available for the supply of 213Bi.

The properties of the Bi3+ ion have been described in the 212Pb section (vide supra). In the case of 213Bi, no prior coordination of a softer metal ion is required as 213Bi is directly eluted from the 225Ac/213Bi generator. Thus, bifunctional versions of DOTA are suitable for the incorporation of 213Bi into targeting vectors, but are often found to exhibit slow chelation kinetics at room temperature, and therefore, are not compatible with mAbs.114 DTPA chelates 213Bi more rapidly but the resultant 213Bi-DTPA complex exhibits low kinetic stability.115 Recent efforts have produced mixed macrocyclic systems with acyclic donor components (3p-C-NETA, 3p-C-DEPA, Figure 8) that provide more rapid chelation and enhanced kinetic stability of the resulting radiochemical complex.90,114 Ideal radiolabelling conditions encompass pH5.5 at room temperature. Another chelating system developed specifically for the Pb2+/Bi3+ pair is Me-do2pa by Lima et al. which displays favourable complexation kinetics and high thermodynamic stability. Additional radiochemical studies are underway.116,117

The short half-life of 213Bi is not ideally matched with the typical pharmacokinetics of mAbs. However, a preclinical study with 213Bi-labelled J591 (antibody against PSMA) found complete inhibition of tumour growth, outlining the potential of this conjugate for application in humans.118 213Bi-lintuzumab (213Bi-HuM195 for acute myeloid leukaemia) was part of a clinical trial, and used in combination therapy with chemotherapy.119 Recent applications of 213Bi are centred on more rapidly targeting vectors such as DOTATOC/DOTATE and PSMA-617.120,121

12. Actinium-225 radiolabelled antibodies

225Ac has a 10-day half-life and decays to its short-lived daughter isotope 213Bi, also an α-emitter. 225Ac is provided by three main suppliers: the Institute for Transuranium Elements in Germany, Oak Ridge National Laboratory in USA and the Institute of Physics and Power Engineering in Obninsk, Russia. The current worldwide production of 225Ac is approximately 1.7 Ci per year, which would only provide treatment for a small 100–200 patient cohort. Thus, new or more efficient methods of 225Ac production and isolation are needed. The common approach for 225Ac production is separation from its mother nuclide 229Th (a daughter of 233U) or irradiation of 226Ra or a thorium target with protons in a cyclotron.122 225Ac decays123 to a cascade of 6 daughters until stable 209Bi is obtained, producing in total 4 α- and 3 β-emissions. Some of the intermediate daughters in the decay include 221Fr (t1/2 =4.8 min), 217At (t1/2 = 32.3 ms), and 213Bi (t1/2 = 45.6 min), each of which emits an α-particle. 213Bi also emits a 440 keV γ-ray suitable for imaging.

The lack of stable isotopes of actinium has provided few opportunities to study its coordinative properties. However, recent EXAFS studies have shed light on some characteristics of Ac3+ as well as coordinative preference. Ac3+ has an ionic radius of 1.12 Å, and absolute hardness of 14.5 eV.86 XAFS studies on the Ac3+ (aq.) complex revealed a coordination number of 10–11, predicting a need for polydentate chelators beyond the usual octadentate DTPA and DOTA-type chelators.124,125 Limited studies have been carried out on the development of novel chelators for this radionuclide, but reported work includes extended polyaza-macrocycle systems HEHA and PEPA.126 However, radiolabelling properties and in vivo stability did not significantly improve when compared with DOTA, underscoring the need for novel, custom bifunctional chelators for Ac3+. This need has been addressed by recent work from Wilson and co-workers by development of the extended macrocyclic chelator macropa (Figure 8) and its bifunctional analogue. Macropa incorporates ether and amino donors within the macrocycle as well as bidentate picolinate donor arms to match the size and hardness of Ac3+, showing promise for targeted applications.127

Due to the limited access to 225Ac, only a handful of human studies have been carried out, but both preclinical and clinical work on therapeutic applications of this isotope has provided promising treatment outcomes. Multiple clinical trials involving 225Ac lintuzumab, an anti-CD33 mAb (HuM195) for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia are on-going, taking advantage of the multi-daughter decay scheme of 225Ac as an advantage over the 213Bi-analogue; Preliminary data shows a three orders of magnitude greater potency of 225Ac-HuM195 when compared with 213Bi-HuM195 (www.clinicaltrials.gov).128

13. Conclusion

The wide range of nuclear properties and half-lives of radiometals represent a tremendous opportunity to develop the next generation of imaging agents and therapeutics for personalised medicine. As the number of radiopharmaceuticals for imaging in the clinic increases, the switch in focus from diagnostic imaging to targeted radiotherapy is likely to continue in the near future. Given the importance of mAbs as biologics, radiotracers for RIT are set to become more prominent players in the nuclear medicine arsenal. In this context, as the personalised medicine gains traction, the need for radiometals will grow. The combination of imaging (pharmacokinetics, clearance, dosimetry) to optimize subsequent therapy provides a unique approach to treatment planning and will lead to an increased number of favourable clinical outcomes. Currently, there is need for new bifunctional chelates that offer improved radiolabelling characteristics for many radiometal systems including established radionuclides like 64Cu, 67Ga, 89Zr, 111In and 177Lu, as well as emerging radionuclides like 212Pb and 225Ac. Progress in this arena is key to propel non-standard radionuclides into the mainstay of nuclear medicine, radiology and oncology.

Acknowledgments

JPH thanks the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF Professorship PP00P2_163683), the European Research Council (ERC-StG-2015, NanoSCAN – 676904) and the University of Zurich for financial support. EB thanks Stony Brook University for start-up funding, as well as NHLBI for a K99 Pathway to Independence award (K99HL125728).

References

- 1.Wu AM, Senter PD. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(9):1137. doi: 10.1038/nbt1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh G. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(9):917. doi: 10.1038/nbt0910-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boswell CA, Brechbiel MW. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34(7):757. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moek KL, Giesen D, Kok IC, de Groot DJA, Jalving M, Fehrmann RSN, Lub-de Hooge MN, Brouwers AH, de Vries EGE. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(Supplement 2):83S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.186940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warram JM, De Boer E, Sorace AG, Chung TK, Kim H, Pleijhuis RG, Van Dam GM, Rosenthal EL. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014;33(2–3):809. doi: 10.1007/s10555-014-9505-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milenic DE, Brady ED, Brechbiel MW. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(6):488. doi: 10.1038/nrd1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennler P, Fischer E, Schibli R. Antibodies. 2015;4(3):197. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agarwal P, Bertozzi CR. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26(2):176. doi: 10.1021/bc5004982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeglis BM, Davis CB, Aggeler R, Kang HC, Chen A, Agnew BJ, Lewis JS. Bioconjug Chem. 2013;24(6):1057. doi: 10.1021/bc400122c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price EW, Orvig C. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43(1):260. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60304k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleuren EDG, Versleijen-Jonkers YMH, Heskamp S, van Herpen CML, Oyen WJG, van der Graaf WTA, Boerman OC. Mol Oncol. 2014;8(4):799. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland JP, Williamson MJ, Lewis JS. Molecular Imaging. 2010:1–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirick GR, O’Donnell RT, Denardo SJ, Shen S, Meares CF, Denardo GL. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26(7):841. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mcdevitt MR, Finn RD, Sgouros G, Ma D, Scheinberg DA. Appl Radiat Isot. 1999;50:895. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(98)00151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruggiero A, Villa CH, Holland JP, Sprinkle SR, May C, Lewis JS, Scheinberg DA, McDevitt MR. Int J Nanomedicine. 2010;5(1):783. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blower PJ, Lewis JS, Zweit J. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23(8):957. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson CJ, Connett JM, Schwarz SW, Rocque Pa Guo LW, Philpott GW, Zinn KR, Meares CF, Welch MJ. J Nucl Med. 1992;33(9):1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mastren T, Pen A, Peaslee GF, Wozniak N, Loveless S, Essenmacher S, Sobotka LG, Morrissey DJ, Lapi SE. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6706. doi: 10.1038/srep06706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadas T, Wong E, Weisman G, Anderson C. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(1):3. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shokeen M, Anderson CJ. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42(7):832. doi: 10.1021/ar800255q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Persson I. Pure Appl Chem. 2010;82(10):1901. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brechbiel MW. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;46(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland JP, Aigbirhio FI, Betts HM, Bonnitcha PD, Burke P, Christlieb M, Churchill GC, Cowley AR, Dilworth JR, Donnelly PS, Green JC, Peach JM, Vasudevan SR, Warren JE. Inorg Chem. 2007;46(2):465. doi: 10.1021/ic0615628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philpott GW, Schwarz SW, Anderson CJ, Dehdashti F, Connett JM, Zinn KR, Meares CF, Cutler PD, Welch MJ, Siegel Ba. J Nucl Med. 1995;36(10):1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philpott GW, Siegel BA, Schwarz SW, Connett JM, Rocque PA, Fleshman JW, Wallis JW, Baumann M, Sun Y, Martell AE, Welch MJ. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37(8):782. doi: 10.1007/BF02050143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connett JM, Anderson CJ, Guo LW, Schwarz SW, Zinn KR, Rogers BE, Siegel BA, Philpott GW, Welch MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(13):6814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kukis DL, DeNardo GL, DeNardo SJ, Mirick GR, Miers LA, Greiner DP, Meares CF. Cancer Res. 1995;55(4):878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Donnell RT, DeNardo GL, Kukis DL, Lamborn KR, Shen S, Yuan AN, Goldstein DS, Carr CE, Mirick GR, DeNardo SJ. J Nucl Med. 1999;40(12):2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeNardo SJ, DeNardo GL, Kukis DL, Shen S, Kroger La, DeNardo Da, Goldstein DS, Mirick GR, Salako Q, Mausner LF, Srivastava SC, Meares CF. J Nucl Med. 1999;40(2):302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis MR, Boswell Ca, Laforest R, Buettner TL, Ye D, Connett JM, Anderson CJ. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2001;16(6):483. doi: 10.1089/10849780152752083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kukis DL, Diril H, Greiner DP, Denardo SJ, Denardo GL, Salako QA, Meares CF. Cancer. 1994;73(3 S):779. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3+<779::aid-cncr2820731306>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamura K, Kurihara H, Yonemori K, Tsuda H, Suzuki J, Kono Y, Honda N, Kodaira M, Yamamoto H, Yunokawa M, Shimizu C, Hasegawa K, Kanayama Y, Nozaki S, Kinoshita T, Wada Y, Tazawa S, Takahashi K, Watanabe Y, Fujiwara Y. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(11):1869. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.118612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mortimer JE, Bading JR, Park JM, Frankel PH, Carroll MI, Tran TT, Poku EK, Rockne RC, Raubitschek AA, Shively JE, Colcher DM. J Nucl Med. 2017;(626) doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.193888. jnumed.117.193888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurihara H, Hamada A, Yoshida M, Shimma S, Hashimoto J, Yonemori K, Tani H, Miyakita Y, Kanayama Y, Wada Y, Kodaira M, Yunokawa M, Yamamoto H, Shimizu C, Takahashi K, Watanabe Y, Fujiwara Y, Tamura K. EJNMMI Res. 2015;5:8. doi: 10.1186/s13550-015-0082-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ping Li W, Meyer LA, Capretto DA, Sherman CD, Anderson CJ. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2008;23(2):158. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2007.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niu G, Sun X, Cao Q, Courter D, Koong A, Le QT, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(7):2095. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng D, Guo Y, White AG, Cai Z, Modi J, Ferdani R, Anderson CJ. Mol Pharm. 2014;11(11):3980. doi: 10.1021/mp500004m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holland JP, Sheh Y, Lewis JS. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36(7):729. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi T, Sasaki T, Takagi I, Moriyama H. J Nucl Sci Technol. 2007;44(February 2014):90. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwarzenbach G, Schwarzenbach K. Helv Chim Acta. 1963;22(1902):1390. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holland JP, Divilov V, Bander NH, Smith-Jones PM, Larson SM, Lewis JS. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(8):1293. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.076174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holland JP, Vasdev N. Dalt Trans. 2014;43(26):9872. doi: 10.1039/c4dt00733f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holland JP, Caldas-Lopes E, Divilov V, Longo Va, Taldone T, Zatorska D, Chiosis G, Lewis JS. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rylova SN, Del Pozzo L, Klingeberg C, Tonnesmann R, Illert AL, Meyer PT, Maecke HR, Holland JP. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(1):96. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.162735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heneweer C, Holland JP, Divilov V, Carlin S, Lewis JS. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(4):625. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.083998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abou DS, Ku T, Smith-Jones PM. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38(5):675. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heskamp S, Raavé R, Boerman OC, Rijpkema M, Goncalves V, Denat F. Bioconjug Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00325. acs. bioconjchem.7b00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deri MA, Ponnala S, Kozlowski P, Burton-Pye BP, Cicek HT, Hu C, Lewis JS, Francesconi LC. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26(12):2579. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deri MA, Ponnala S, Zeglis BM, Pohl G, Dannenberg JJ, Lewis JS, Francesconi LC. J Med Chem. 2014;57(11):4849. doi: 10.1021/jm500389b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tinianow JN, Pandya DN, Pailloux SL, Ogasawara A, Vanderbilt AN, Gill HS, Williams SP, Wadas TJ, Magda D, Marik J. Theranostics. 2016;6(4):511. doi: 10.7150/thno.14261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patra M, Bauman A, Mari C, Fischer CA, Blacque O, Häussinger D, Gasser G, Mindt TL. Chem Commun. 2014;50(78):11523. doi: 10.1039/c4cc05558f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma MT, Meszaros LK, Paterson BM, Berry DJ, Cooper MS, Ma Y, Hider RC, Blower PJ. Dalt Trans. 2015;44(11):4884. doi: 10.1039/c4dt02978j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boros E, Holland JP, Kenton N, Rotile N, Caravan P. Chempluschem. 2016;81(3):274. doi: 10.1002/cplu.201600003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwertmann U. Plant Soil. 1991;130:1. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vosjan MJWD, Perk LR, Visser GWM, Budde M, Jurek P, Kiefer GE, van Dongen GAMS. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(4):739. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pandit-Taskar N, O’Donoghue JA, Beylergil V, Lyashchenko S, Ruan S, Solomon SB, Durack JC, Carrasquillo JA, Lefkowitz RA, Gonen M, Lewis JS, Holland JP, Cheal SM, Reuter VE, Osborne JR, Loda MF, Smith-Jones PM, Weber WA, Bander NH, Scher HI, Morris MJ, Larson SM. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2014:2093–2105. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2830-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morris MJ, Pandit-Taskar N, Carrasquillo JA, O’Donoghue JA, Humm J, Lyashchenko SK, Haupt EC, Bander NH, Tagawa ST, Holland JP, Smith-Jones PM, Lewis JS, Solomon SB, Scher HI, Larson SM. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(6) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pandit-Taskar N, O’Donoghue JA, Durack JC, Lyashchenko SK, Cheal SM, Beylergil V, Lefkowitz RA, Carrasquillo JA, Martinez DF, Fung AM, Solomon SB, Gönen M, Heller G, Loda M, Nanus DM, Tagawa ST, Feldman JL, Osborne JR, Lewis JS, Reuter VE, Weber WA, Bander NH, Scher HI, Larson SM, Morris MJ. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(23):5277. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koizumi M, Endo K, Kunimatsu M, Sakahara H, Nakashima T, Kawamura Y, Watanabe Y, Saga T, Konishi J, Yamamuro T, Hosoi S, Toyama S, Arano Y, Yokoyama A. Cancer Res. 1988;48(5):1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Govindan SV, Michel RB, Griffiths GL, Goldenberg DM, Mattes MJ. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32(5):513. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Othman MF bin, Mitry NR, Lewington VJ, Blower PJ, Terry SYA. Nucl Med Biol. 2017;46:12. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ryan KP, Dillman RO, DeNardo SJ, DeNardo GL, Beauregard J, Hagan PL, Amox DG, Clutter ML, Burnett KG, Rulot CM. Radiology. 1988;167(1):71. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.1.3347750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alberto R, Braband H. SPECT/PET Imaging with Technetium, Gallium, Copper, and Other Metallic Radionuclides. Vol. 3 Elsevier Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Quigley AM, Gnanasegaran G, Buscombe JR, Hilson AJW. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17(6):447. doi: 10.1159/000151565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adam MJ, Wilbur DS. Chem Soc Rev. 2005;34(2):153. doi: 10.1039/b313872k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watkinson JC, Maisey MN. J R Soc Med. 1988;81(11):653. doi: 10.1177/014107688808101114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hamill TG, Duggan ME, Perkins JJ. J Label Comp Radiopharm. 2001;44(1):55. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pentlow KS, Graham MC, Lambrecht RM, Daghighian F. J Nucl Med. 1996;37(9):1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McConahey PJ, Dixon FJ. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1966;29(2):185. doi: 10.1159/000229699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Markwell MAK. Anal Biochem. 1982;125(2):427. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salacinski PRP, McLean C, Sykes JEC, Clement-Jones VV, Lowry PJ. Anal Biochem. 1981;117(1):136. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90703-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilbur DS. Bioconjugate Chem. 1992;3(6):433. doi: 10.1021/bc00018a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaminski MS, Tuck M, Estes J, Kolstad A, Ross CW, Zasadny K, Regan D, Kison P, Fisher S, Kroll S. New Engl J Med. 2005;352(5):441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Press OW, Eary JF, Gooley T, Gopal AK, Liu S, Rajendran JG, Maloney DG, Petersdorf S, Bush SA, Durack LD. Blood. 2000;96(9):2934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lebovic D, Kaminski MS, Anderson TB, Detweiler-Short K, Griffith KA, Jobkar TL, Kandarpa M, Jakubowiak A. Am Soc Hematology. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 76.DeNardo GL, DeNardo SJ, Goldstein DS, Kroger LA, Lamborn KR, Levy NB, McGahan JP, Salako Q, Shen S, Lewis JP. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(10):3246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.10.3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shapiro WR, Carpenter SP, Roberts K, Shan JS. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6(5):539. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hdeib A, Sloan AE. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11(6):799. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.579097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen S, Yu L, Jiang C, Zhao Y, Sun D, Li S, Liao G, Chen Y, Fu Q, Tao Q. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1538. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Braghirolli AMS, Waissmann W, da Silva JB, dos Santos GR. Appl Radiat Isot. 2014;90:138. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Verel I, Visser GWM, Vosjan MJWD, Finn R, Boellaard R, van Dongen GAMS. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31(12):1645. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1632-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tijink BM, Perk LR, Budde M, Stigter-van Walsum M, Visser GWM, Kloet RW, Dinkelborg LM, Leemans CR, Neri D, van Dongen GAMS. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36(8):1235. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1096-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wadas TJ, Wong EH, Weisman GR, Anderson CJ. Chem Rev. 2010;110(5):2858. doi: 10.1021/cr900325h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chinol M, Hnatowich DJ. J Nucl Med. 1987;28(9):1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Herzog H, Tellmann L, Scholten B, Coenen HH, Qaim SM. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52(2):159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Parr RG, Pearson RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105(26):7512. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jang YH, Blanco M, Dasgupta S, Keire DA, Shively JE, Goddard WA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121(26):6142. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stimmel JB, Stockstill ME, Kull FC., Jr Bioconjugate Chem. 1995;6(2):219. doi: 10.1021/bc00032a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kobayashi H, Wu C, Yoo TM, Bao-Fu S. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(5):829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kang CS, Sun X, Jia F, Song HA, Chen Y, Lewis M, Chong HS. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012;23(9):1775. doi: 10.1021/bc200696b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Price EW, Edwards KJ, Carnazza KE, Carlin SD, Zeglis BM, Adam MJ, Orvig C, Lewis JS. Nucl Med Biol. 2016;43(9):566. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Witzig TE, Gordon LI, Cabanillas F, Czuczman MS, Emmanouilides C, Joyce R, Pohlman BL, Bartlett NL, Wiseman GA, Padre N. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(10):2453. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thompson S, Ballard B, Jiang Z, Revskaya E, Sisay N, Miller WH, Cutler CS, Dadachova E, Francesconi LC. Nucl Med Biol. 2014;41(3):276. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kulik LM, Atassi B, Van Holsbeeck L, Souman T, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, Hunter RD, Nemcek AA, Abecassis MM, Haines KG. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94(7):572. doi: 10.1002/jso.20609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lindén O, Hindorf C, Cavallin-Ståhl E, Wegener WA, Goldenberg DM, Horne H, Ohlsson T, Stenberg L, Strand S-E, Tennvall J. Clin Can Res. 2005;11(14):5215. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Salako QA, O’Donnell RT, DeNardo SJ. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(4):667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cwikla JB, Sankowski A, Seklecka N, Buscombe JR, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, Jeziorski KG, Mikolajczak R, Pawlak D, Stepien K, Walecki J. Ann Oncol. 2009;21(4):787. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dvorakova Z, Henkelmann R, Lin X, Türler A, Gerstenberg H. Appl Radiat Isot. 2008;66(2):147. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]