Abstract

Background

Little is known about fertility desire in HIV-positive female sex workers (FSW). Fertility desire could increase HIV transmission risk if it were associated with condomless sex or lower adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted among 255 HIV-positive FSWs in Mombasa, Kenya. Using generalized estimating equations, fertility desire was evaluated as a risk factor for semen detection in vaginal secretions by prostate specific antigen (PSA) test, a biomarker of condomless sex, detectable plasma viral load (VL), and HIV transmission potential, defined as visits with positive PSA and detectable VL.

Results

The effect of fertility desire on PSA detection varied significantly by non-barrier contraception use (p-interaction<0.01). At visits when women reported not using non-barrier contraception, fertility desire was associated with higher risk of semen detection (82/385, 21.3% versus 158/1007,15.7%; aRR 1.58, 95%CI 1.12–2.23). However, when women used non-barrier contraception, fertility desire was associated with lower risk of PSA detection (10/77,13.0% vs.121/536, 22.6%; aRR 0.58, 95%CI 0.35–0.94). Fertility desire was not associated with detectable VL (31/219,14.2% vs.128/776,16.5%; aRR 0.82, 95%CI 0.46–1.45) or higher absolute risk of transmission potential (10/218, 4.6% vs. 21/769, 2.7%; adjusted risk difference=0.011, 95%CI −0.031–0.050).

Conclusion

Fertility desire was associated with higher risk of biological evidence of semen exposure when women were not using non-barrier contraceptives. Low HIV transmission potential regardless of fertility desire suggests that the combination of condoms and ART adherence was effective.

INTRODUCTION

Expanded access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Africa offers HIV-positive women the opportunity to live longer, resume sexual relationships, and become pregnant with substantially reduced risk of HIV transmission to HIV-negative partners and infants [1–4]. Unmet need for contraception and unintended pregnancy among HIV-positive women has been described [5, 6], with increased attention to fertility desire and need for safer conception [7]. Recent population-based surveys suggest that 7% to 40% of HIV-positive women in Africa desire more children [5, 8, 9]. Fertility desire, without adequate counseling for safer conception, could be an important risk factor for secondary HIV transmission if women engage in more condomless sex despite having a detectable viral load.

Women who are HIV-positive and engage in condomless sex can greatly reduce the risk of HIV transmission through consistent adherence to ART and resultant viral suppression [10, 11]. Fertility desire could be associated with higher rates of viral suppression if women believe that taking ART in pregnancy will reduce their risk transmitting HIV to their sex partner and their baby [12]. Conversely, fertility desire could increase the risk of detectable viral load if women interrupt HIV treatment due to concerns about medication toxicities to the fetus [13] or fear of abandonment by a partner upon learning her HIV status [14, 15].

Female sex workers (FSWs) in Africa are a key population at high risk for HIV acquisition, and for HIV transmission to sexual partners [7, 16]. In Kenya, 14% of HIV transmission is due to sex work [17], with potentially higher rates with regular partners because of lower condom use [18]. This population has a high frequency of unintended pregnancy and risk of vertical transmission [8]. Use of non-barrier methods of contraception among FSWs has been low in several studies [8, 19],ranging from 12% to 54% [19, 20]. The most common non-barrier methods that FSWs use are hormonal injectables and pills [7, 19, 20]. Combination prevention programs for HIV-positive FSWs, which emphasize consistent condom use and high adherence to ART to prevent onward transmission, focus on reducing their risk of transmitting HIV to sex partners [8, 21]. While pregnancy prevention is emphasized, women’s fertility preferences are typically not addressed [22]. Despite stigma related to sex work and HIV-status, many HIV-positive FSWs desire more children [22–24]. Studies exploring fertility desire in relation to risk factors for HIV transmission in FSWs are lacking [23]. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a prospective cohort study of fertility desire as a risk factor for condomless sex (using prostate specific antigen [PSA] test as a biologic marker), detectable plasma viral load, and transmission potential (visits when both PSA detection and a detectable viral load were present), in HIV-positive FSWs in Mombasa, Kenya.

METHODS

Women were recruited for this prospective cohort study between October 2012 and December 2015 from an ongoing cohort at Ganjoni Clinic, a primary venue for FSW STI testing and treatment in Mombasa for over three decades. Ongoing recruitment of new participants occurred through outreach at bars 2–8 times per month. Eligible women were laboratory-confirmed HIV-positive, ≥18 years old, had initiated ART, and reported ever exchange of sex for cash or in-kind payment. Detailed methods for this cohort have been published [25]. Women were excluded from this analysis if they were pregnant or post-menopausal. At enrollment, women completed a standardized face-to-face interview to collect socio-demographic, health, and behavioral data. A study clinician conducted a physical examination including a speculum-assisted pelvic examination to collect genital swabs for laboratory testing. Participants returned monthly for behavioral data collection. Physical examinations and genital sample collection for detection of semen and STIs were repeated quarterly, and blood samples were collected for viral load testing every six months. Participants received free medical care at the research clinic, counseling on consistent adherence to ART and condom use for health promotion and prevention of onward HIV transmission, demonstrations on correct condom use, if needed, non-barrier contraceptive options (oral contraceptives, hormonal injections, intra-uterine contraceptive devices), STI treatment, and ART according to Kenyan National Guidelines. At each visit, participants were compensated 250 Kenyan shillings (about $2.50). This study was approved by the ethics committees of Kenyatta National Hospital and the University of Washington. All participants provided written informed consent.

Fertility desire was assessed quarterly by asking a question adapted from the Kenyan Demographic and Health Survey: “Do you want any/more children?” [26]. Women who responded yes were asked about fertility intent by asking: “Are you trying to get pregnant now?”

This study had two primary outcomes. Semen was detected in vaginal secretions by PSA test, collected at quarterly examination visits (ABACard, West Hills, CA). This biomarker is most sensitive for detecting semen within 24–48 hours after condomless sex [27]. Detectable plasma viral load, examined every three months, was defined as ≥180 copies/mL (Hologic, Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA). This cut-point was higher than the assay lower limit of detection (<30 copies/mL), because some 100 mL samples had to be diluted 6-fold, to a final volume of 600 mL before testing. Because results were not available in real time, women did not know their viral load status during the study.

HIV transmission potential was defined as occurring at visits when both semen detection by PSA test and detectable plasma viral load were present. The relationship between fertility desire and HIV transmission potential was evaluated as an exploratory outcome.

A secondary analysis was conducted to evaluate fertility desire as a risk factor for self-reported condomless sex. Sexual behavior data were collected monthly. Any condomless sex in the past week was defined as the number of total sex acts exceeding the number of sex acts with a condom, as in our prior studies [28, 29]Because this outcome was highly skewed, we created a binary variable to represent any versus no condomless less.. Sensitivity analyses were performed with additional self-reported sexual behavioral outcomes (Supplementary Table 1). In a separate secondary analysis, fertility desire was evaluated as a risk factor for poor adherence to ART. This variable was defined as >48 hours late for a scheduled refill based on research pharmacy data (‘late refill’, hereafter) [30].

Covariate data were collected at enrollment, and time-updated at different intervals depending on the measure. Characteristics included age; years in sex work; early sexual debut (<15 years vs. ≥15); highest education level (<8 years vs ≥8); workplace (bar, nightclub, home/other); number of live births; postpartum status (≤9 months since last birth); and use of any non-barrier contraceptive method. Modern non-barrier contraception, collected monthly, was defined as methods with a typical-use failure rate of less than 10% per year (injectable hormonal contraception, oral contraceptives, intrauterine device,) compared to condoms only or no method [31]. Women were asked quarterly to identify whether they had a regular male sex partner (boyfriend or husband), who was not a client or casual partner (yes/no). Women were asked annually about that regular partner’s expected reaction to a future pregnancy (excited, neutral, upset). Exposure to controlling behaviors (yes to ≥1 of 7 acts ever) and to any intimate partner violence (IPV) by the regular partner (yes to ≥1 of 13 acts past 12 months) were measured annually as in our prior studies [25, 32], using items adapted from a global violence against women survey [33].

Depressive symptoms in the past two weeks were assessed 6-monthly by Patient Health Questionnaire-9 ([PHQ-9], 0–4 [minimal], 5–9 [mild], 10 or higher [moderate or severe]) [34]. Alcohol use in the past year was assessed annually by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test ([AUDIT], 0 [non-drinkers], 1–6 [minimal], 7–15 [moderate], and ≥16 [possible alcohol use disorder]) [35]. Disclosure of HIV status was assessed 6-monthly by asking whether women had ever shared their results with someone, and if so, with whom [36].

Statistical analysis

Women contributed survey and laboratory data to this analysis from October 2012 until administrative censoring (December 31, 2015). Fertility desire status was carried forward for intervening visits until the next quarterly assessment to permit analyses with outcomes and covariate data that occurred between quarterly visits.

The primary analyses tested the hypotheses that fertility desire was associated with higher risk of semen detection by PSA test and, separately, with higher risk of detectable viral load [13]. We also explored whether fertility desire was associated with higher risk of HIV transmission potential events.

In the analysis of fertility desire as a risk factor for semen detection by PSA test, effect modification by non-barrier contraceptive use was evaluated based on the hypothesis that the relationship between fertility desire and condomless sex would differ depending on whether women reported using a modern non-barrier contraceptive method. An interaction term between fertility desire and non-barrier contraceptive use was entered into a model that included the outcome, fertility desire, and any non-barrier contraceptive use. If the p-value for the interaction term was <0.10 using a Wald test, we performed stratified analyses.

Log-binomial generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with independence working correlation structure and robust standard errors were used to generate relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) [37]. Multivariate model-building evaluated pre-specified confounding factors based on prior studies [9, 23, 38–40]. Variables that changed the relative risk estimate by >10% in univariate analyses were retained in the multivariate model [41] Conceptual diagrams of the proposed relationships between variables are provided in a supplementary digital appendix (Figures 1 and 2). Age (continuous) and number of live births (continuous) were pre-specified potential confounding factors included in the multivariate model [40]. Additional variables were each tested for association with the outcome in a separate univariate model. These factors included sociodemographic characteristics, age of first sex, alcohol use, depressive symptoms, IPV in the past year, HIV disclosure to anyone other than a healthcare provider, and disclosure to a husband or boyfriend. Variables were entered into a regression model in descending order of the size of their RRs in unadjusted analyses. In the event of collinearity, the more plausible confounding factor was retained in the model. For subgroup analyses by non-barrier modern contraceptive use, model building was performed separately in each stratum. Additional exploratory analyses were conducted using fertility intent as an exposure.

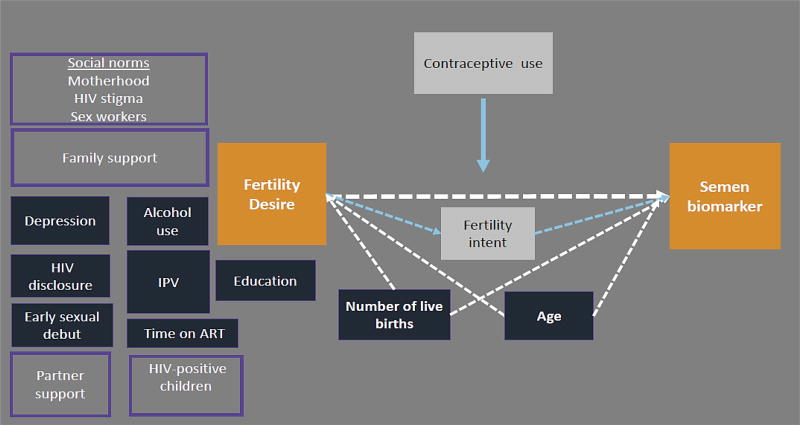

Figure 1. Conceptual diagram of fertility desire in relation to a biomarker of condomless sex in HIV-positive FSWs in Kenya.

Conceptual diagram of a plausible relationship between the fertility desire and biologic evidence of unprotected sex (orange boxes). Variables that were evaluated as potential confounding factors are shown in dark blue. Number of live births and age were retained in the final adjusted model and therefore are connected to the exposure and outcome by dotted white arrows. Fertility intent (white box) is a likely mechanism linking fertility desire and unprotected sex. Social and family factors that were not measured in this analysis, but may influence the primary association, are shown in light purple boxes.

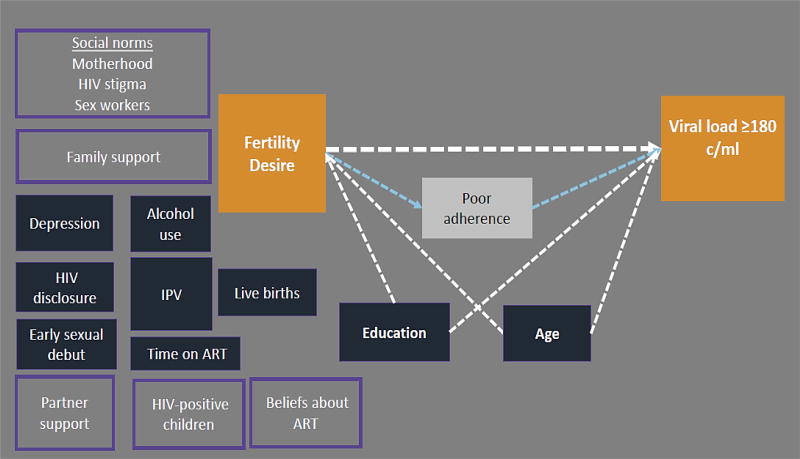

Figure 2. Conceptual diagram of fertility desire in relation to detectable plasma viral load in HIV-positive FSWs in Kenya.

Conceptual diagram of a plausible relationship between the fertility desire and detectable viral load (orange boxes). Variables that were evaluated as potential confounding factors are shown in dark blue. Education level and age were retained in the final adjusted model, and are connected to the exposure and outcome by dotted white arrows. Poor adherence (white box) is a likely mechanism linking fertility desire to detectable viral load. Unmeasured individual, family, and social factors that were not measured in this analysis, but may influence the primary association, are shown in light purple boxes (e.g. partner support).

To evaluate the association between fertility desire and detectable viral load in six monthly visits with viral load data, we included age and education level as pre-specified confounding factors based on our conceptual diagram (Figure 2). Secondary analyses of fertility desire and late refill, a marker for poor adherence, used the final adjusted model from the viral load analysis.

The exploratory analysis of fertility desire and HIV transmission potential included visits with both PSA and viral load data, with age as the only pre-specified confounding factor because age was the common confounding factor in the PSA and viral load analyses. Because the combined outcome was less frequent than the individual outcomes (31/981 visits, 3.1%), these analyses used GEE linear regression with robust standard errors to estimate the absolute risk (risk difference [RD]) of HIV transmission potential events, comparing visits with and without fertility desire.

Missing exposure and covariate data were <2%, and missing outcomes were <10% (PSA, <1%, viral load data, <7%). Therefore, a complete case analysis was performed. All analyses were conducted in STATA 13.0 (College Station, TX).

Power calculations were performed separately for each primary aim, accounting for correlation of observations within women. A sample of 2,000 visits for the PSA analysis was expected to provide >80% power to detect a RR ≥1.6 overall, and >80% power to detect a RR ≥1.8 for sub-group analyses of PSA detection. A target of 990 visits in the viral load analysis was required to provide >80% power to detect a RR ≥1.8 for detectable viral load.

RESULTS

Overall, 255 women contributed 475 person years to the analyses. The median number of follow-up visits per women was 19 (interquartile range (IQR) 7–33). Baseline characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. Median age was 38 years (33–42), and median time in sex work was 9 years (5–14). Most women reported having a regular emotional partner (i.e., boyfriend or husband; 208/255, 82.0%). One quarter of women reported fertility desire (65/255, 25.5%). Fertility desire was modestly higher at visits when women reported having a regular partner (370/1,534 visits (24.3%) compared to 92/487 (18.9%); χ2=6.05, p-value=0.014). About one third of women reported using a modern non-barrier contraceptive method (79/255, 30.9%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants (N=255)

| N (%) or median IQR | |

|---|---|

| Age | 38 [33–42] |

| Highest education (less than 8 years) | 97 (38.0) |

| Years in sex work | 9 [5–14] |

| Workplace | |

| Bar/Restaurant | 151 (59.2) |

| Nightclub | 61 (23.9) |

| Home/Other | 43 (16.9) |

| Ever married | 189 (74.1) |

| Has an index partner who is not a client1 | 208 (81.6) |

| Casual partner (non-client) in the last 3 months | 112 (43.9) |

| Ever controlling behaviors by the regular partner2 | 122 (47.8) |

| Number of previous births (n=254) | 2 [1–3] |

| Fertility desire | 65 (25.5) |

| Fertility intent | 26 (10.2) |

| Contraceptive use by method duration | |

| None, condoms only | 176 (69.0) |

| DMPA or OCP | 49 (19.2) |

| IUD, Norplant | 30 (11.8) |

| Index partner attitude about pregnancy | |

| Excited | 119 (56.5) |

| Neutral | 48 (22.9) |

| Upset | 43 (20.5) |

| No index partner | 45 (17.6) |

| Depressive symptoms by PHQ-9 | |

| Minimal (0–4) | 184 (72.2) |

| Mild (5–9) | 51 (20.0) |

| Mod/Severe (10 or higher) | 20 (7.8) |

| Alcohol use problems by AUDIT | |

| Non-drinkers | 141 (55.3) |

| Minimal (1–6) | 64 (25.1) |

| Moderate (7–15) | 43 (16.9) |

| Severe/possible AUD (16 or higher) | 7 (2.8) |

| Disclosed HIV status to anyone in the past | 182 (71.7) |

| Ever disclosed to a boyfriend or husband | 58 (22.7) |

| Any IPV in the past year by the index partner | 52 (20.4) |

| Sexual violence by another person in the past year3 | 19 (7.4) |

| Physical violence by another person in the past year3 | 20 (7.9) |

| CD4 count ≤350 mm3 | 85 (33.3) |

| HIV clinical stage (3 or 4) | 89 (34.9) |

| Time on ART (years)4 | 4.5 [2.2–7.1] |

ART, antiretroviral therapy ; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; DMPA, Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate; IPV, intimate partner violence; IQR, interquartile range; OCP, oral contraceptive pills; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9;

Index partner refers to a woman’s current or most recent regular partner (boyfriend or husband) who was not a client. If she did not have an index partner, she was asked to refer to her most recent index partner. All IPV questions refer to acts committed by this partner.

Asked of women who were not currently pregnant at that visit.

These questions refer to someone other than the index partner.

Based on self-report or pharmacy records.

Fertility desire and semen detection by PSA test

The analysis of fertility desire as a risk factor for semen detection by PSA test included 255 women and 2,011 quarterly examination visits. Desire for more children was common (453/1,985, 22.8% of visits in 90 women). Semen detection by PSA test occurred at 373/2,011 (18.6%) visits in 152 women. We found evidence of effect modification by non-barrier contraceptive use (interaction p-value=0.004), so results are presented separately in visits where women reported use of modern methods and visits when they did not (Table 2). At visits where women reported not using non-barrier contraception, fertility desire was associated with higher risk of semen detection by PSA test (82/385, 21.3% versus 158/1,007, 15.7%; RR 1.36, 95%CI 0.97–1.90). This association increased, and became statistically significant, in the model adjusted for age and number of live births (aRR 1.58, 95%CI 1.12–2.23). In exploratory analyses, fertility intent was also associated with higher risk of positive PSA when women reported no modern contraception (94/340 (27.7%) vs.1961,232 (15.9); aRR 1.95, 95% CI: 1.32–2.90). In contrast, at visits when women reported using modern non-barrier contraception, fertility desire was associated with significantly lower risk of semen detection by PSA in unadjusted analysis (10/77, 13.0% versus 121/536, 22.6%; RR 0.58, 95%CI 0.36–0.92), and in the final model adjusting for age, number of live births, and age of first sex (aRR 0.58, 95%CI 0.35–0.94) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Association between fertility desire and semen detection by PSA test, secondary self-reported behavioral outcomes, and STIs, stratified by use of modern non-barrier contraceptive methods

| Outcome | Visits with fertility desire |

Visits without fertility desire |

RR (95% CI) | p-value | aRR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits when women reported not using any modern non-barrier contraceptive method | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| PSA detected | 82/385 (21.3) | 158/1007 (15.7) | 1.36 (0.97, 1.90) | 0.07 | 1.55 (1.05, 2.29)1 | 0.01 |

| Condomless sex in past week2 | 130/878 (14.8) | 199/2,338 (8.5) | 1.74 (1.00, 3.04) | 0.05 | 1.74 (1.00, 3.11)3 | 0.04 |

|

| ||||||

| Visits when women reported using any modern non-barrier contraceptive method | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| PSA detected | 10/77 (13.0) | 121/536 (22.6) | 0.58 (0.36, 0.92) | 0.02 | 0.58 (0.35, 0.95)4 | 0.03 |

| Condomless sex in past week2 | 46/180 (25.6) | 101/1,252 (8.1) | 3.17 (1.38, 7.29) | 0.01 | 2.55 (1.23, 5.73)5 | 0.01 |

RR, Relative Risk; aRR, adjusted Relative Risk; PSA, prostate specific antigen test

The final multivariate models were adjusted for age (continuous) and number of live births at enrollment (continuous), and included 196 women and 1,383 examination visits.

Data on condomless sex were collected monthly.

The final multivariate model was adjusted for age (continuous), number of live births at enrollment (continuous), and included 171 women and 1,639 visits.

The final multivariate model was adjusted for age, number of live births, and age of first sex (binary), and included 100 women and 613 examination visits.

The final multivariate model was adjusted for age, number of live births, and age of first sex (binary), including 92 women and 855 visits.

Table 3.

Association between fertility desire, detectable plasma viral load, and late ART refills

| Outcome | Visits with fertility desire |

Visits without fertility desire |

RR (95% CI) | p-value | aRR (95% CI)1 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral load 180≥copies/ml2 | 31/219 (14.2) | 128/776 (16.5) | 0.86 (0.47, 1.57) | 0.62 | 0.88 (0.43, 1.78) | 0.50 |

| Late refill (>48 hours)3 | 204/923 (22.1) | 611/3,181 (19.2) | 1.15 (0.88, 1.50) | 0.30 | 1.04 (0.79, 1.36) | 0.60 |

RR, Relative Risk; aRR, adjusted Relative Risk

Final models were adjusted for age (continuous) and education level (binary).

Model with viral load outcome (collected every 6 months) included 240 women and 995 visits.

Model with adherence outcome (collected monthly) included 212 women and 4,104 visits.

In analyses of self-reported sexual behavior, fertility desire was associated with higher risk of self-reported condomless sex in the past week in the sub-group of visits where women reported not using modern non-barrier contraception, after adjusting for age and number of live births (aRR 1.58, 95%CI 1.12–2.23). Interestingly, and in contrast to results from the PSA analysis, in the sub-group of visits when women were using a non-barrier method, fertility desire was also associated with higher risk of self-reported condomless sex, after adjusting for age, number of live births, and age of first sex (aRR 2.55, 95%CI 1.23–5.73).

Fertility desire, detectable viral load, and poor adherence to ART

Overall, 240 women contributed 995 visits (386 person-years) to the viral load analysis, and 212 women contributed 4,104 visits to the adherence analysis (28 women had missing outcomes). Detectable plasma viral load occurred at 159/995 (16.0%) visits in 66 women. Fertility desire was not associated with detectable viral load in the unadjusted model, or after adjusting for age and education level (31/219, 14.2% vs. 128/776, 16.5%; aRR 0.82, 95%CI 0.46–1.44) (Table 3). While late refills were common (815/4,104 monthly visits, 19.9%), fertility desire was not associated with late refill (aRR 1.08, 95%CI 0.82–1.41).

Fertility desire and HIV transmission potential

HIV transmission potential events occurred at only 31/987 (3.1%) visits in 19 women. Fertility desire was not associated with significantly higher absolute risk of HIV transmission potential events in the unadjusted analysis (10/218, 4.6% vs. 21/769, 2.7%, RD 0.02, 95%CI −0.017, 0.050), or in the final model adjusted for age and male partner controlling behaviors (aRD 0.011, 95%CI −0.031 – 0.050).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of HIV-positive female sex workers enrolled in HIV treatment in Kenya, fertility desire was associated with higher risk of biological evidence of condomless sex only when women reported not using non-barrier contraception. Fertility desire was not associated with higher risk of detectable plasma viral load. Episodes of HIV transmission potential were infrequent regardless of fertility desire. These results suggest that combination prevention, focused on condom use and ART adherence to reduce transmission risk, may be effective even in FSWs who report that they desire more children.

Results from this prospective cohort study expand upon findings from prior cross-sectional studies by showing a temporal relationship between reports of fertility desire and unprotected sex, using biomarker evidence of condomless sex, and examining differences in this association by non-barrier contraceptive use. Cross-sectional studies of HIV-positive FSWs in West Africa and general population women in Uganda have found that fertility desire was associated with a higher proportion of self-reported condomless sex [23, 42]. However, a cohort study in general population HIV-positive women in Uganda did not find an association between fertility desire and self-reported condomless sex [40]. These differing findings may be due to differences in measures and study populations.

A unique feature of this study was our finding that the association between fertility desire and condomless sex differed by non-barrier contraceptive use. Notably, fertility desire was associated with lower risk of semen detection in in visits where women were using non-barrier methods, which may suggest that these women were actively preventing pregnancy in the near term while still desiring a future pregnancy.

In this era of combination HIV prevention, an important finding in this study was the low number of HIV transmission potential events. While viral suppression was below the United Nations target of 90%, it was higher than reported in previous studies in FSWs in Africa [43, 44]. Although the sub-group of women who were not using non-barrier contraception and desired an additional child had increased risk of biologic evidence of condomless sex, we observed no increased risk of events suggestive of HIV transmission potential. This indicates that the combination of ART and condom use was effective at minimizing episodes of concurrent unprotected sex and detectable plasma viral load [45]. A more deliberate effort to provide preconception counseling for these women could help to support safer conception. This approach could emphasize confirmation of viral load suppression, followed by timed condomless sex during periods of peak fertility, to minimize risk of HIV transmission and STI acquisition [8, 22].

In this study, we found substantial underreporting of unprotected sex compared to semen detection by PSA test. This finding is consistent with our prior study comparing biologic and self-reported measures of condomless sex in this cohort [46]. Self-reported condomless sex measures recalled behavior and willingness to report it. Interestingly, in women not using non-barrier contraception, both PSA and self-reported data suggested that fertility desire was associated with more condomless sex. In contrast, among women using non-barrier contraception, PSA results suggested less condomless sex, while self-report suggested more. This striking difference in PSA versus self-reported behavior indicates that HIV-positive women using non-barrier contraceptives may be more comfortable reporting condomless sex compared to women who do not use any method besides condoms [47].

This study had several strengths. The longitudinal cohort design with time-updated exposure and outcome measurements permitted evaluation of temporal relationships between fertility desire and condomless sex, viral load, and episodes representing HIV transmission potential. Biomarker endpoints added rigor to these findings. A standardized measure of fertility desire was used, enhancing comparability with prior studies [39, 40, 48]. An ongoing complementary qualitative study in this cohort will help to clarify pathways linking fertility desire, contraceptive use, and sexual behavior. Finally, this study focused on HIV-positive FSWs, which could inform tailoring of combination HIV prevention programs for this key population [22].

This study also had limitations. First, we evaluated fertility desire with a single question, which may not have fully captured women’s fertility preferences [49]. Qualitative studies in HIV-positive women reveal that women may experience varying degrees of fertility desire, depending on their relationships, HIV-status disclosure, and concern about perceived risk of HIV transmission [15, 38]. Second, fertility desire is a sensitive topic in HIV-positive women and is subject to social desirability bias. Fertility desire may have been over-reported because of social expectations for women to bear children [14, 50, 51], or underreported if some women feared being judged by the provider for wanting more children despite the risk of HIV transmission [21, 38]. Condomless sex may have differed by partner type. Our sexual behavior measures were not partner-specific. Finally, the sample included HIV-positive FSWs receiving care at a research clinic, with median age of 38. The relationship between fertility desire and HIV transmission risk indicators may differ in FSWs who are not receiving HIV care tailored to this key population and in younger women. Specifically, FSWs desiring more children who are not on ART likely have elevated risk of HIV transmission potential [3].

CONCLUSION

Fertility desire was common in this cohort of HIV-positive FSWs on ART, but did not appear to increase HIV transmission risk. Even in women who desired more children and were not using contraception other than condoms, events representing HIV transmission potential were rare. This finding suggests that combination prevention emphasizing consistent condom use and ART adherence is effective in this key population. Assessment of fertility desire among HIV-positive FSWs in HIV services should be routine. Understanding women’s fertility desires, whether and when they want more children in the future, would help to tailor appropriate contraceptive options and safer conception counseling. These services could help women to realize their reproductive goals while also protecting their own health and the health of their partners and future children [52, 53].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the study participants and our research, clinical, laboratory, outreach, and administrative staff for making this study possible. This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01HD072617). K.S.W. was supported by the University of Washington Center for STD and AIDS (grant T32 AI07140). Infrastructure and logistics support for the Mombasa research site was provided by the University of Washington’s Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI027757) which is supported by the following centers: NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NCCAM. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: No conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Litwin LE, Makumbi FE, Gray R, Wawer M, Kigozi G, Kagaayi J, et al. Impact of Availability and Use of ART/PMTCT Services on Fertility Desires of Previously Pregnant Women in Rakai, Uganda: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:377–384. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaida A, Laher F, Strathdee SA, Janssen PA, Money D, Hogg RS, et al. Childbearing intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HAART in an HIV hyperendemic setting. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:350–358. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day S, Graham SM, Masese LN, Richardson BA, Kiarie JN, Jaoko W, et al. A prospective cohort study of the effect of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate on detection of plasma and cervical HIV-1 in women initiating and continuing antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:452–456. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ngugi EW, Kim AA, Nyoka R, Ng'ang'a L, Mukui I, Ng'eno B, et al. Contraceptive practices and fertility desires among HIV-infected and uninfected women in Kenya: results from a nationally representative study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(Suppl 1):S75–81. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mak J, Birdthistle I, Church K, Friend-Du Preez N, Kivunaga J, Kikuvi J, et al. Need, demand and missed opportunities for integrated reproductive health-HIV care in Kenya and Swaziland: evidence from household surveys. AIDS. 2013;27(Suppl 1):S55–63. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz S, Papworth E, Thiam-Niangoin M, Abo K, Drame F, Diouf D, et al. An urgent need for integration of family planning services into HIV care: the high burden of unplanned pregnancy, termination of pregnancy, and limited contraception use among female sex workers in Cote d'Ivoire. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(Suppl 2):S91–98. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz SR, Papworth E, Ky-Zerbo O, Sithole B, Anato S, Grosso A, et al. Reproductive health needs of female sex workers and opportunities for enhanced prevention of mother-to-child transmission efforts in sub-Saharan Africa. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015 doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-100968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taulo F, Berry M, Tsui A, Makanani B, Kafulafula G, Li Q, et al. Fertility intentions of HIV-1 infected and uninfected women in Malawi: a longitudinal study. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(Suppl 1):20–27. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khademi A, Anand S, Potts D. Measuring the Potential Impact of Combination HIV Prevention in Sub-Saharan Africa. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1453. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekker LG, Johnson L, Cowan F, Overs C, Besada D, Hillier S, et al. Combination HIV prevention for female sex workers: what is the evidence? Lancet. 2015;385:72–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60974-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sofolahan YA, Airhihenbuwa CO. Cultural expectations and reproductive desires: experiences of South African women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA) Health Care Women Int. 2013;34:263–280. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.721415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngarina M, Tarimo EA, Naburi H, Kilewo C, Mwanyika-Sando M, Chalamilla G, et al. Women's preferences regarding infant or maternal antiretroviral prophylaxis for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV during breastfeeding and their views on Option B+ in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith DJ, Mbakwem BC. Life projects and therapeutic itineraries: marriage, fertility, and antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 5):S37–41. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000298101.56614.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kisakye P, Akena WO, Kaye DK. Pregnancy decisions among HIV-positive pregnant women in Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12:445–454. doi: 10.1080/13691051003628922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:538–549. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelmon L, Kenya P, Oguya F, Cheluget B, Hailee G. In: Kenya: HIVPrevention response and modes of transmission analysis. Council NAC, editor. Nairobi, Kenya: National AIDS Control Council; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voeten HA, Egesah OB, Varkevisser CM, Habbema JD. Female sex workers and unsafe sex in urban and rural Nyanza, Kenya: regular partners may contribute more to HIV transmission than clients. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:174–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decker MR, Yam EA, Wirtz AL, Baral SD, Peryshkina A, Mogilnyi V, et al. Induced abortion, contraceptive use, and dual protection among female sex workers in Moscow, Russia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;120:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutherland EG, Alaii J, Tsui S, Luchters S, Okal J, King'ola N, et al. Contraceptive needs of female sex workers in Kenya - a cross-sectional study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2011;16:173–182. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2011.564683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhana A, Luchters S, Moore L, Lafort Y, Roy A, Scorgie F, et al. Systematic review of facility-based sexual and reproductive health services for female sex workers in Africa. Global Health. 2014;10:46. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz SR, Papworth E, Ky-Zerbo O, Anato S, Grosso A, Ouedraogo HG, et al. Safer conception needs for HIV prevention among female sex workers in Burkina Faso and Togo. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:296245. doi: 10.1155/2014/296245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aho J, Koushik A, Rashed S. Reasons for inconsistent condom use among female sex workers: need for integrated reproductive and prevention services. World Health Popul. 2013;14:5–13. doi: 10.12927/whp.2013.23442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duff P, Shoveller J, Feng C, Ogilvie G, Montaner J, Shannon K. Pregnancy intentions among female sex workers: recognising their rights and wants as mothers. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41:102–108. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson KS, Deya R, Masese L, Simoni JM, Vander Stoep A, Shafi J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence in HIV-positive women engaged in transactional sex in Mombasa, Kenya. Int J STD AIDS. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0956462415611514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macro I, editor. Kenya_National_Bureau_of_Statistics, National_AIDS_Control_Council, National_AIDS/STD_Control_Programme, National_Public_Health_Laboratory_Services, Kenya_Medical_Research_Institute, National_Coordinating_Agency_for_Population_and_Development Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hochmeister MN, Budowle B, Rudin O, Gehrig C, Borer U, Thali M, et al. Evaluation of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) membrane test assays for the forensic identification of seminal fluid. J Forensic Sci. 1999;44:1057–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Wanje GH, Graham SM, Mutunga E, Peshu N, et al. Association Between Participant Self-Report and Biological Outcomes Used to Measure Sexual Risk Behavior in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1-Seropositive Female Sex Workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820369f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson KS, Deya R, Yuhas K, Simoni J, Vander Stoep A, Shafi J, et al. A Prospective Cohort Study of Intimate Partner Violence and Unprotected Sex in HIV-Positive Female Sex Workers in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:2054–2064. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham SM, Masese L, Gitau R, Jalalian-Lechak Z, Richardson BA, Peshu N, et al. Antiretroviral adherence and development of drug resistance are the strongest predictors of genital HIV-1 shedding among women initiating treatment. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1538–1542. doi: 10.1086/656790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson KS, Wanje G, Yuhas K, Simoni JM, Masese L, Vander Stoep A, et al. A Prospective Study of Intimate Partner Violence as a Risk Factor for Detectable Plasma Viral Load in HIV-Positive Women Engaged in Transactional Sex in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:2065–2077. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1420-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omoro SA, Fann JR, Weymuller EA, Macharia IM, Yueh B. Swahili translation and validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression scale in the Kenyan head and neck cancer patient population. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:367–381. doi: 10.2190/8W7Y-0TPM-JVGV-QW6M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peltzer K, Chao LW, Dana P. Family planning among HIV positive and negative prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) clients in a resource poor setting in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:973–979. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wekesa E, Coast E. Fertility desires among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Nairobi slums: a mixed methods study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner GJ, Wanyenze R. Fertility Desires and Intentions and the Relationship to Consistent Condom Use and Provider Communication Regarding Childbearing Among HIV Clients in Uganda. ISRN Infect Dis. 2013;2013 doi: 10.5402/2013/478192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Homsy J, Bunnell R, Moore D, King R, Malamba S, Nakityo R, et al. Reproductive intentions and outcomes among women on antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda: a prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wanyenze RK, Matovu JK, Kamya MR, Tumwesigye NM, Nannyonga M, Wagner GJ. Fertility desires and unmet need for family planning among HIV infected individuals in two HIV clinics with differing models of family planning service delivery. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:5. doi: 10.1186/s12905-014-0158-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huet C, Ouedraogo A, Konate I, Traore I, Rouet F, Kabore A, et al. Long-term virological, immunological and mortality outcomes in a cohort of HIV-infected female sex workers treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy in Africa. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:700. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konate I, Traore L, Ouedraogo A, Sanon A, Diallo R, Ouedraogo JL, et al. Linking HIV prevention and care for community interventions among high-risk women in Burkina Faso--the ARNS 1222 "Yerelon" cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(Suppl 1):S50–54. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182207a3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayer KH, Venkatesh KK. Interactions of HIV, other sexually transmitted diseases, and genital tract inflammation facilitating local pathogen transmission and acquisition. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65:308–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Norwood MS, Hughes JP, Amico KR. The validity of self-reported behaviors: methods for estimating underreporting of risk behaviors. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:612–618. e612. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Surie DYK, Wilson K, Masese L, Shafi J, Kinuthia J, Jaoko W, McClelland RS. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, WA: 2017. Modern contraceptive use and unprotected sex in high-risk HIV-positive women in Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maier M, Andia I, Emenyonu N, Guzman D, Kaida A, Pepper L, et al. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased fertility desire, but not pregnancy or live birth, among HIV+ women in an early HIV treatment program in rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(Suppl 1):28–37. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9371-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreau C, Trussell J, Bajos N. Contraceptive paths of adolescent women undergoing an abortion in France. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Todd CS, Stibich MA, Laher F, Malta MS, Bastos FI, Imbuki K, et al. Influence of culture on contraceptive utilization among HIV-positive women in Brazil, Kenya, and South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:454–468. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9848-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beyeza-Kashesya J, Kaharuza F, Mirembe F, Neema S, Ekstrom AM, Kulane A. The dilemma of safe sex and having children: challenges facing HIV sero-discordant couples in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9:2–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.World_Health_Organization, editor. Salamander_Trust. Building a safe house on firm ground: key findings from a global values and preferences survey regarding the sexual and reproductive health and human rights of women living with HIV. Geneva, Switzertand: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.World_Health_Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.