INTRODUCTION

Painful neuromas of the peripheral nerves are psychologically and physically disabling [36]. Painful neuroma usually develops following trauma or surgery [12, 73, 92], affecting 2–60% of patients with a nerve injury [1, 29, 34]. There is no consensus on the optimal treatment of painful neuroma. Consequently, numerous modalities to treat neuroma pain are described, including pharmacologic, psychologic, and physical interventions [66, 74, 93].

The role of surgery in the treatment of painful neuroma remains controversial [13, 22, 30]. A wide variety of surgical techniques are described to treat painful neuroma. Studies of these techniques have been limited by small sample sizes and non-randomized case series study designs; therefore, no definitive answer on the effectiveness of surgical management of neuroma pain exists.

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to identify and assess the available information on the outcomes of surgical treatment of painful neuromas. Our goals were to determine the overall effectiveness of surgery, determine if certain surgical procedures are more effective than others, and perform confounding and bias analysis not previously possible because of the small patient numbers in most published studies.

METHODS

Search Strategy

In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, we sought to identify all clinical studies on surgical treatment of neuroma using a predesigned protocol for computerized literature search of the online databases Embase, Scopus, PubMed, Cochrane library, and ClinicalTrials.gov [62]. We conducted searches up until June 2015 without language restrictions. Search terms were MeSH headings, text words, and variations of the key words or phrases: neuroma, pain, peripheral, extremity, operate, management, outcome, visual analogue scale, quality of life, and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire [41]. Titles and abstracts were reviewed and articles retrieved if they seemed relevant or there was uncertainty. Retrieved articles were assessed using inclusion and exclusion criteria and citation lists of retained articles were searched for relevant citations.

Study Selection

Studies reporting the efficacy of the surgical treatment of painful neuromas were included in this meta-analysis. Studies of neuroma prevalence, primary prevention of neuroma, or mechanisms of painful neuroma formation were not included in our analysis. Studies reporting treatment of neuromas not in the extremities or specifically dealing with nerve compression and Morton’s neuroma (a distinct clinical entity more akin to nerve compression) were excluded. Case-reports, non-sequential patient series, and studies only reported in abstract form were excluded to reduce selection bias within studies.

The primary outcome analyzed was proportion of patients with meaningful reduction of pain. Outcomes reporting varied across studies and included patient satisfaction, surgeon examination, and ordinal pain scales such as the visual analogue scale. Therefore, we defined a meaningful reduction of pain as a pain score reduction of 3 or more, final visual analogue pain less than 4, or patient or surgeon report of meaningful improvement as defined in each study.

Data Extraction and Validity Scoring

Two authors independently assembled the following information for each study: year of publication, period of time that surgeries were performed, surgical technique performed, outcome definition, age range of study population at the time of surgery, duration of pain symptoms prior to surgery, number of previous neuroma pain operations, affected extremity and nerve, and confounding variables (socioeconomic status, employment status, workman’s compensation or other litigation, and smoking). Studies were grouped according to surgical technique employed. Surgical techniques were categorized as excision-only, excision and cap (with any device intended to stop regeneration), excision and transposition (surgical movement of the nerve from its native course into bone, muscle, or vein), excision and repair (direct or nerve graft repair), or neurolysis and coverage with transposed soft tissue (muscle, fascial, or adipose flap) (Table 1). Where disagreement among data extractors arose, adjudication was accomplished by a third reader and discussion among authors.

Table 1.

Reports of Outcomes Studies of Surgical Treatment for Painful Neuroma

| 1st Author | Year | Country | Type of Surgery | Location | Mean follow-up (months) |

Quality Score (15 point scale) |

# Patients/ Group |

# improved (% success) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Adani R. [3] | 2014 | Italy | Neurolysis & Coverage | UE | 41.5 | 6.5 | 8 | 6 (75%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Adani R. [2] | 2002 | Italy | Neurolysis & Coverage | UE | 23.2 | 5.5 | 9 | 8 (89%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Atherton D. [5] | 2008 | UK | Excise & Transpose | UE | 32 | 7 | 33 | 28 (85%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Atherton D. [6] | 2007 | UK | Excise & Transpose | UE | NR, 6 mo. minimum | 6.5 | 33 | 25 (76%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Atherton D. [4] | 2007 | UK | Excise & Transpose | UE | 33.7 | 7.5 | 7 | 6 (86%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Balcin H. [7]* | 2009 | Switzerland | Excise & Transpose | LE | 12 | 12.5 | 10 | 4 (40%) |

| Excise & Transpose | 10 | 6 (60%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Barbera J. [8] | 1993 | Spain | Excise & Cap | LE | 15 | 6 | 22 | 21 (95%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Bek D. [9] | 2006 | Turkey | Excise Only | UE | 71.5 | 7 | 14 | 14 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Bourke H. [10] | 2011 | UK | Excise Only | LE | NR | 5.5 | 10 | 5 (50%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Burchiel K. [11] | 1993 | USA | Excise & Transpose | NR | 11 | 3.5 | 18 | 8 (44%) |

| Excise & Transpose | 10 | 4 (40%) | ||||||

| Neurolysis & Coverage | 5 | 0 (0%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Chiodo C. [14] | 2004 | USA | Excise & Transpose | UE | 27 | 11 | 14 | 9 (64%) |

| Excise & Transpose | 12 | 14 | 13 (93%) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Dellon A. [18] | 2005 | USA | Excise Only | LE | NR, 6 mo. minimum | 9 | 13 | 10 (77%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Dellon A. [19] | 2004 | USA | Excise & Transpose | UE | 16.8 | 9.5 | 9 | 9 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Dellon A. [16] | 2002 | USA | Excise & Transpose | UE | NR | 3 | 27 | 27 (100%) |

| Excise Only | 4 | 3 (75%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Dellon A. [17] | 1998 | USA | Excise & Transpose | LE | 29.5 | 7 | 11 | 9 (82%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Dellon A. [20] | 1986 | USA/Canada | Excise & Transpose | UE & LE | 31 | 10 | 60 | 53 (88%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Ducic I. [25] | 2010 | USA | Excise & Transpose | LE | 34 | 9.5 | 35 | 29 (83%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Ducic I. [26] | 2008 | USA | Excise & Transpose | LE | 22.8 | 10.5 | 21 | 20 (95%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Elliot D. [27]* | 2010 | UK | Neurolysis & Coverage | UE | 19 | 11 | 14 | 10 (72%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Evans G. [28] | 1994 | USA | Excise & Transpose | UE | 19 | 11 | 13 | 12 (92%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Guse D. [36] | 2013 | USA | Excise & Transpose | UE | 240 | 10.5 | 11 | 6 (55%) |

| Excise Only | 17 | 7 (41%) | ||||||

| Excise & Repair | 28 | 23 (82%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Hazari A. [37] | 2004 | UK | Excise & Transpose | UE | NR, 2 mo. minimum | 6 | 35 | 34 (97%) |

| Excise & Transpose | 13 | 13 (100%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Herbert T. [38] | 1998 | Australia | Excise & Transpose | UE | 15 | 8.5 | 14 | 9 (64%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Herndon J. [39] | 1976 | USA | Neurolysis & Coverage | UE | 30 | 6 | 15 | 12 (80%) |

| Neurolysis & Coverage | 18 | 12 (67%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Kakinoki R. [45] | 2003 | Japan | Excise & Transpose | UE | 23 | 7 | 10 | 7 (70%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Kakinoki R. [44] | 2008 | Japan | Excise & Repair | UE | 17 | 10 | 9 | 9 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Kandenwein J. [46] | 2006 | Germany | Excise & Repair | UE | 51 | 8 | 3 | 0 (0%) |

| Excise & Transpose | 8 | 1 (13%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Kim J. [47] | 2001 | Korea/USA | Excise & Transpose | LE | 18.5 | 9.5 | 16 | 13 (81%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Koch H. [48] | 2011 | Austria | Excise & Transpose | UE & LE | 43.6 | 8 | 25 | 23 (92%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Koch H. [49] | 2003 | Austria | Excise & Transpose | UE & LE | 26.5 | 8 | 23 | 20 (87%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Krishnan K. [51] | 2005 | Germany | Neurolysis & Coverage | UE & LE | 18.3 | 10 | 3 | 3 (100%) |

| Excise Only | 15.3 | 4 | 4 (100%) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Laborde K. [52] | 1982 | USA | Excise Only | UE | NR | 2 | 32 | 13 (41%) |

| Excise & Transpose | 6 | 4 (67%) | ||||||

| Excise & Repair | 4 | 2 (50%) | ||||||

| Neurolysis & Coverage | 8 | 8 (100%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Lanzetta M. [53] | 2000 | Italy | Excise Only | UE | NR, 6 mo. minimum | 7 | 7 | 7 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Loh Y. [55] | 1998 | England | Excise Only | UE | NR | 6 | 6 | 5 (83%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Mackinnon S. [56] | 1987 | USA/Canada | Excise & Transpose | UE | NR | 10 | 52 | 42 (81%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Martins R. [59] | 2014 | Brazil | Excise & Repair | UE | 28.3 | 10.5 | 7 | 7 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Masquelet A. [60] | 1987 | France | Excise & Transpose | UE | NR | 5 | 20 | 18 (90%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Nahabedian M. [63]* | 2001 | USA | Excise & Transpose | LE | 28 | 10.5 | 25 | 21 (84%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Noordenbos W. [67] | 1981 | Netherlands/England | Excise & Repair | UE & LE | NR, 20 mo. minimum | 8.5 | 5 | 1 (20%) |

| Excise Only | 2 | 0 (0%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Novak C. [68] | 1995 | USA/Canada | Excise & Transpose | UE | 60 | 10.5 | 70 | 45 (64%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Resiman N. [75] | 1983 | USA | Neurolysis & Coverage | UE | 22.1 | 7 | 12 | 11 (92%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Rose J. [76] | 1996 | USA | Neurolysis & Coverage | UE | 24 | 6.5 | 8 | 8 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Sarris I. [77] | 2002 | USA | Excise & Transpose | UE | 26 | 8 | 8 | 8 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Sehirlioglu A. [78] | 2007 | Turkey | Excise Only | LE | 33.6 | 6 | 75 | 75 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Souza J. [80] | 2012 | USA | Excise Only | LE | 25.7 | 7 | 7 | 6 (86%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Spauwen P. [82] | 1999 | Netherlands | Neurolysis & Coverage | UE | 24 | 8 | 10 | 9 (90%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Stahl S. [84] | 2002 | Israel | Excise Only | UE | 6 | 10 | 3 | 2 (66%) |

| Excise & Transpose | 9 | 9 (100%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Stahl S. [83] | 1999 | Israel | Excise & Cap | UE | NR | 8 | 2 | 2 (100%) |

| Excise & Repair | 9 | 9 (100%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Stokvis A. [85]*$ | 2010 | Netherlands | Excise & Transpose | UE | 22 | 8.5 | 19 | 7 (37%) |

| Excise & Repair | 6 | 3 (50%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Tennent T. [86] | 1998 | England | Excise Only | LE | NR | 4 | 3 | 3 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Thomas M. [87] | 1994 | England | Excise & Repair | UE & LE | 12 | 6.5 | 20 | 3 (15%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Thomsen L. [88] | 2010 | France | Excise & Repair | UE | 11.8 | 7.5 | 10 | 10 (100%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Tupper J. [90] | 1976 | USA | Excise Only | UE | 12.1 | 3.5 | 153 | 98 (64%) |

| Excise & Cap | 24.6 | 17 | 7 (41%) | |||||

| Excise & Cap | 17 | 28 | 19 (68%) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Vaienti L. [92] | 2013 | Italy | Excise & Transpose | UE | 12 | 11 | 8 | 4 (50%) |

UE – upper extremity; LE – lower extremity; NR – not reported;

- prospective study;

- randomized trial.

To assess quality of information in each study, we developed a 15-point scoring technique modeled on the Downs and Black checklist for assessing methodological quality of non-randomized studies (Appendix 1) [24]. Specifically, we assessed the clarity of the surgery performed, the precision of the outcomes reported, whether information on potential confounders was reported, whether complications of bad outcomes were reported, and quality of bias analysis. Recognizing the limitations of quality scoring to account for bias among studies [35, 40, 43], detailed data was collected on study characteristics thought most likely to bias study results, namely objectivity of the outcome reported, follow-up duration, the proportion of patients lost to follow-up, and known confounders for successful relief of pain when available. Using this scale, a higher number equates with higher quality of information presented.

Statistical Analysis

Raw categorical data from relevant studies were used to calculate proportions with 95% confidence intervals of patients who experienced a meaningful reduction of pain. Individual proportions were combined by means of DerSimonian-Laird random-effects models given the variety of surgical techniques, geographic locations, and patient populations among studies [21, 65]. A continuity correction of 0.1 was used for studies with a proportion of zero or one. Cochran’s Q and Higgins I2 tests were used to assess heterogeneity among studies. Given the modest statistical power of these tests we considered heterogeneity as significant if p<0.1 or I2>30%.

We explored sources of heterogeneity with stratified analysis of group differences when significant heterogeneity was noted among studies for a confounder and when more than fifteen studies reported the confounder of interest. Stratified analyses examining surgical group differences were performed for confounding variables. For studies with multiple surgical groups, confounding information for each surgical group was used when available. Otherwise, mean or median data from each study as a whole was applied to each group to allow categorization. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using a Bonferroni correction to compare multiple groups.

Meta-regression was also used to explore sources of heterogeneity. After calculating the log odds ratio of patients with meaningful reduction of pain and standard error of the log odds ratio, a forward, step-wise meta-regression was performed with potential confounding variables as covariates. Confounders were considered significant in the model if they altered the β-coefficient for surgery type by more than ten percent [58]. We assessed publication bias graphically using Hunter’s method for creating funnel plots and formally tested funnel asymmetry using Peters’ test[42, 71]. All statistical analyses were performed using StataIC 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) and the METAPROP, METAREG, and METAFUNNEL software packages.

RESULTS

Sources

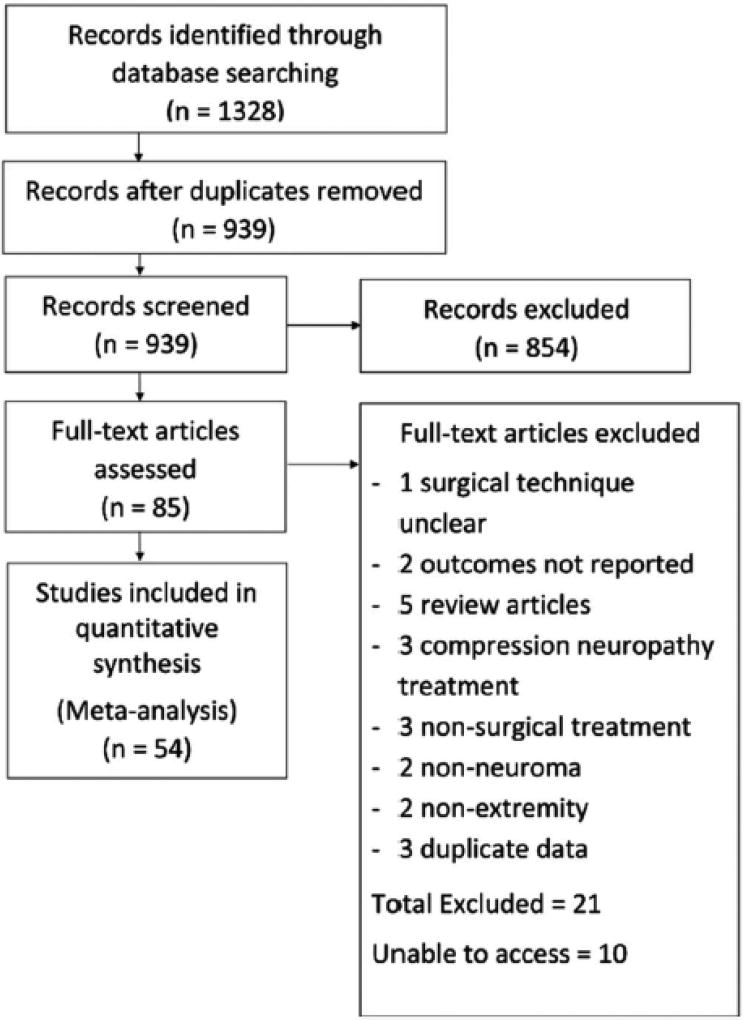

Our electronic literature search and review of bibliographies identified 1,328 studies. After abstract review excluding duplications and studies not relevant to the subject of interest, 85 full text studies were reviewed. After exclusion of studies not meeting inclusion criteria, 54 studies reporting 74 treatment groups and results for 1381 patients were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Selection Process

The reviewed studies were conducted over a period of more than 30 years (1976–2015), in 16 countries, reflecting a variety of medical practices and reporting techniques. Among the 54 included studies, four studies (7%) were conducted prospectively. Thirty-nine (72%) studies reported outcomes for a single surgical technique, 11 (20%) reported outcomes for 2 techniques, 3 (6%) presented 3 techniques, and 1 (2%) reported 4 techniques. In general, each technique correlated with a treatment group; however, six studies described multiple techniques that were categorized into the same treatment group. Excision and transposition was the most commonly reported technique for treating neuroma, with 34 studies (63%) including this group. Nineteen studies (35%) included an excision only group, 11 studies (20%) included a neurolysis and coverage group, 10 studies (19%) included an excise and repair group, and 4 studies (7%) included an excise and cap group (table 1).

Thirty-five studies (65%) reported treatment of neuromas in the upper extremity, 12 (22%) reported on lower extremity neuromas, and 6 (11%) reported on neuromas in both upper and lower extremities. One study (2%) did not specify neuroma location but did include intra-operative photographs of the upper extremities. Thirty-six studies (67%) reported results after treatment of cutaneous sensory nerve neuromas, 11 studies (20%) reported results after treatment of major nerve (e.g. ulnar, median, sciatic) neuromas, and 5 studies (9%) reported results for both. Two studies (4%) did not specify if major or cutaneous nerve were treated.

In the included studies, the mean age of patients was 41.6 ± 7.1 years. The median follow-up was 24 months [Interquartile range (IQR): 17 – 31] and the median duration of symptoms prior to surgery reported was 21 months [IQR: 10 – 41]. The median percentage of patients who had one or more prior operations for neuroma pain among studies was 29% [IQR: 0–1].

Patient identification

Forty-eight studies (89%) reported clearly how they diagnosed neuromas in their patients. In all cases, the physical exam was the primary method of neuroma identification. Twenty-nine studies (54%) supplemented this with a diagnostic nerve block. Three studies (6%) also used an MRI or ultrasound to aid in diagnosis.

Outcomes reporting

Outcomes reporting and duration of follow-up varied widely across studies. Many studies reported numerous outcomes. Thirty-eight studies (70%) used a non-standard ordinal scale such as no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, or severe pain as their primary outcome. Only fifteen studies (28%) included a 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS) to report pain, and only 8 (15%) used it as a primary outcome. Four studies (8%) used patient satisfaction as a primary outcome. Four studies (8%) reported a reduction in pain on physical exam or improved functional status as the primary outcome. One study (2%) reported only that all patients had complete pain relief and were able to return to normal activities. One study (2%) determined success of treatment from decreased use of analgesic pain medication.

Forty-four studies (81%) explicitly reported partial versus complete pain relief. Five studies (9%) reported scores on the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) scale before and after treatment. Fifteen studies (28%) reported patient satisfaction. Most studies (40 of 54 (74%)) reported only mean follow-up duration rather than the timing of outcome assessment. Three studies (6%) reported only a follow-up range and 2 studies (4%) reported minimum follow-up only. Only one study (2%) reported the exact time of outcome assessment.

Quality of Studies

Among the 54 studies included, the quality of information reported was inconsistent, limiting our ability to analyze confounding variables as sources of heterogeneity. On a scale from 0–15, with 0 representing no important information presented and 15 representing most important information presented, the median score was 8.0 [IQR: 6.4 – 10.0]. Studies consistently reported their aims, hypotheses, patient identification criteria and surgical technique. Patient selection, outcomes assessment, and complications were rarely clearly reported.

Sources of Confounding Bias

Based on literature review, we considered the following confounding variables important when assessing outcomes for treatment of painful neuromas: sex, age, duration of symptoms, timing of outcome assessment, number of prior neuroma pain operations, nerve involved, employment status, workers’ compensation claims or pending litigation, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), and socio-economic status. No study reported all of these variables and no study reported why or how confounders were selected. Among studies reporting confounders, only 9 studies (17%) considered confounding in their analysis.

Meaningful Reduction of Pain by Surgery Type

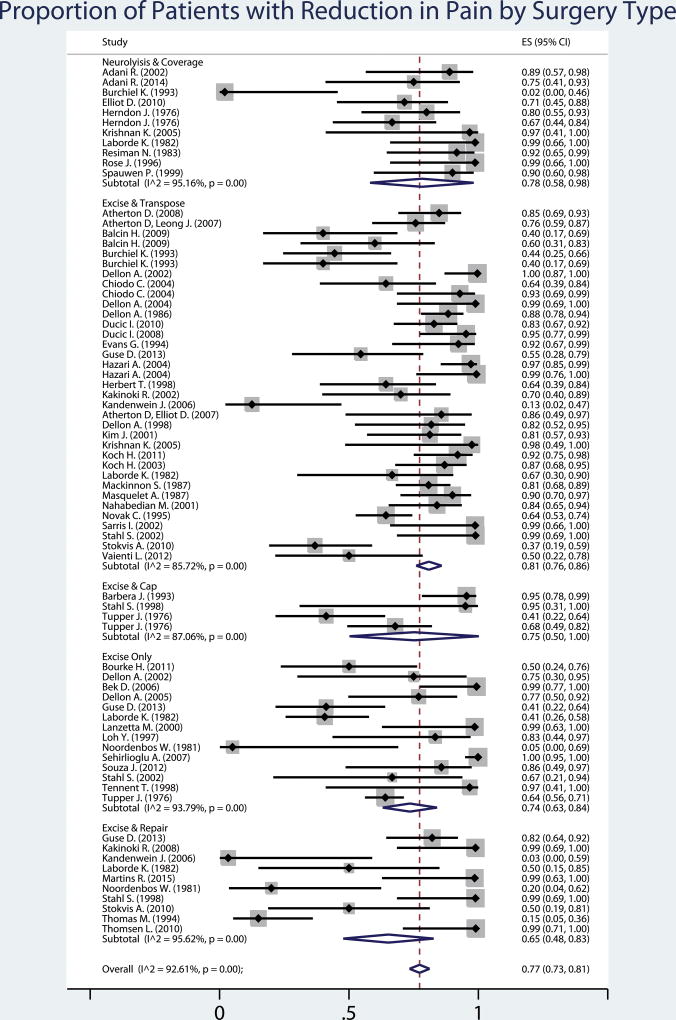

Among all studies, the proportion of patients with a meaningful reduction in pain was 77% [95% confidence interval (CI): 73–83]. When stratified by treatment group, there were no significant differences between treatment groups in the outcome of meaningful reduction in pain (p>0.05). However, the excision and transposition group had the highest proportion of patients with a meaningful pain reduction (81% [95% CI: 75–86]) and the most consistent results. Despite this, a large amount of heterogeneity was observed in all treatment groups, I2 range 85.7% – 95.6% (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fifty-four studies describing 74 groups were included in this meta-analysis of the proportion of patients successfully treated with surgery for neuroma pain. Overall, 77% (95% confidence interval: 73–83) of patients had a meaningful reduction in pain. The type of surgery performed did not make a significant difference to the proportion of patients successfully treated. Square grey boxes with a dot represent the reported proportion of patients with pain reduction. The line surrounding this box represents the 95% confidence interval for that proportion. The blue diamonds represent the estimate of proportion of patients with reduction in pain for each surgery type, and overall, derived from the study groups included using random effects meta-analysis of proportion.

Stratified Analyses

In order to tease out possible guidelines for future surgical treatment of neuromas, stratified analyses examining surgical group differences were performed for confounding variables. These included: age, follow-up duration, symptom duration prior to definitive neuroma surgery, proportion of patients with 1 or more prior neuroma pain surgeries, neuroma location, affected nerve caliber (major nerve vs. cutaneous nerve), primary outcome, study quality, and study publication year. Study groups were categorized according to mean symptom duration reported prior to neuroma surgery into: duration less than 12 months, duration of 12–23 months, duration greater than 24 months, and not reported. Among groups with mean symptoms duration greater than 24 months, excision and transposition (74% patients improved [95% CI: 0.65 – 0.83]) and neurolysis and coverage (91% patients improved [95% CI: 0.80 – 1 .00]) were significantly better than excision and repair (20% patients improved [95% CI: 0.05 – 0.34]), p<0.05 for both comparisons. Among groups with mean symptom duration less than 12 months, or 12–23 months, there were no significant differences between surgery types.

Study groups were categorized according to the proportion of patients who had one or more surgeries for neuroma pain prior to the reported surgery (0–15%, 16–30%, 31–45%, 46–60%, and greater than 60%). Among studies with greater than 60% patients with one or more prior surgeries specifically for neuroma pain, excision and transposition (78% patients improved [95% CI: 0.66 – 0.90]) and neurolysis and coverage (96% patients improved [95% CI: 0.90 – 1.00]) were significantly better than excision only (30% patients improved [95% CI: 0.02 – 0.59]), p<0.05 for both comparisons. No significant differences were seen between surgery types in groups with less than 60% patients with one or more prior operations for pain. No significant differences in the proportion of patients with a meaningful pain reduction among study groups were seen regardless of age, follow-up duration, location (upper v. lower extremity), affected nerve caliber, primary outcome used, study quality, or publication year.

Regression Analysis

Meta-regression was performed to examine for confounding effects of mean age, mean follow-up duration, mean symptom duration, proportion of patients with one or more prior operations, nerve caliber, and primary outcome reported. Within the multiple regression models, the primary outcome reported, mean patient age, and proportion of patients with 1 or more prior operations altered the effect estimate of surgery type on proportion of patients with meaningful improvement after neuroma surgery by more than 10%, suggesting that these factors do confound treatment effect.

Bias Analysis

Funnel plot analysis of study groups was symmetric, suggesting that there was no publication bias among studies (Appendix 2). Peters’ test for publication bias confirmed these results (p=0.24).

DISCUSSION

A wide variety of surgical techniques are described in the literature to treat painful neuroma. Thus, the goal of this meta-analysis of 54 studies reporting outcomes after surgical treatment of painful neuromas was to evaluate surgical effectiveness, establish a hierarchy of effective techniques and delve into the impact of confounders on effective surgical treatment. When evaluating the studies that met inclusion criteria, our data demonstrates that clinically meaningful improvement of pain can be achieved with surgical intervention. However, the most effective surgical technique was not elucidated as we found no significant differences between the various surgical techniques. Further, the overall quality of most of the studies reviewed was low and excitement for these results must be tempered.

Despite the low quality of most of the studies, the large number of studies, surgical groups, and patients included in this meta-analysis allowed for exploration of the role of confounding variables on neuroma surgery outcomes. There was no evidence of publication bias, suggesting the reported outcomes are reliable. Our categorization schema and subdividing patients into surgical groups by technique is a reflection of the surgical literature, descriptions, and experience. This meta-analysis cannot assess if our categorization schema by technique was meaningful and this is a limitation to the study. Subtle differences in technique are not well addressed with a meta-analysis and would require a well-designed trial to flush out. Therefore, we recommend ongoing thoughtful analysis of outcomes and technique by surgeons in conjunction with pain specialists.

Overall, our data suggest most patients with a painful neuroma deemed appropriate surgical candidates by the surgeon will have a meaningful decrease in pain with surgical intervention and that in appropriately selected cases, the dogma that “operating for pain will only result in more pain” may not apply [12, 13, 67]. No information is included about patients with painful neuromas that were not offered surgery. Therefore, any conclusions about the effectiveness of surgery have to be limited to patients deemed appropriate for surgical management, i.e. indicated for surgery by the surgeon. We believe that patient selection and careful attention to correct diagnosis is the key to successful outcomes.

When evaluating patients with painful neuromas, it is essential to distinguish between neuropathic pain due to compression neuropathy, direct nerve injury, or both, bearing in mind the distinct possibility of an associated double-crush phenomenon [90, 94]. Surgical treatment will vary significantly for compression and neurotmetic injury [15, 69]. The distinction requires a detailed history and physical examination. Identifying the appropriate nerve(s) involved in pain generation is critical, especially considering overlap of nerve dermatomes and frequent plexus formation between cutaneous nerves [23, 54, 79]. The importance of active patient participation in correct diagnosis cannot be overemphasized [32]. Further, a multidisciplinary approach to these patients with pain is essential. We recommend the involvement of pain management specialists, physical therapists, and psychological therapists in coming to the diagnosis and decision for surgical intervention. In our experience, misdiagnosis coupled with surgery can make a patient’s pain worse.

Stratified analyses revealed two interesting findings. The first was that excision of a neuroma and transposition of the distal nerve end into muscle, bone, or vein or neurolysis of a neuroma and coverage with healthy vascularized tissue were superior to excision-only or excision and capping in patients who had neuroma pain for more than two years and in patients who had more than one previous surgery specifically to deal with neuroma pain. Why these procedures are superior in these patient populations cannot be answered by this meta-analysis and deserves further study. However, these populations are thought to be the most recalcitrant to surgical treatment because of centralization of their pain [20, 30]. Therefore, due to their severity, these groups may allow the best evaluation of the surgical treatments.

Numerous authors have suggested that the micro-environment can affect painful neuroma formation [33, 45, 72, 96]. Placing the cut nerve end into muscle is shown to decrease neuroma size and myofibroblast infiltration, potentially decreasing pain signaling [57, 95]. Placing the cut nerve end deep within a muscle or under a vascularized flap also protects it from external stimuli, and blocks axon regeneration to the skin [50, 57]. Skin may serve as both a mechanical and biologic irritant, especially in an inflamed, multiply-operated wound bed [61, 70]. Other mechanical irritants should also be carefully observed by limiting tension and motion on the cut nerve end [20]. Our clinical experience with vascularized tissue coverage of a neuroma has not been positive unless the source of neuroma pain is addressed with neuroma excision or neuroma excision and repair [88].

The results of this study are consistent with previously published work stating that 20–30% of neuromas will be refractory to treatment, regardless of type of surgery performed [36, 64]. Initial results can be misleading, and reoperation rates as high as 65% have been reported in some studies [36, 37, 52]. Unfortunately, reoperation rates can be difficult to track and were rarely reported in the included studies. Studies also suggest that neuroma location or size can affect outcomes [20, 31, 36]. In this study, neuroma location in the lower versus upper extremity made no difference. Neuroma size was rarely reported which precluded a meaningful interpretation of its impact.

As with all systematic reviews and meta-analyses, our ability to draw conclusions is limited by the quality of information in the primary studies included. Studies only reported a median of eight, out of fifteen possible, key factors pertinent to patient outcome. All studies failed to include at least one important factor, and most studies failed to report or perform any bias analysis with their results. Although included data was sufficient to perform stratified and multivariate regression analysis, our inability to detect significant differences among treatment groups does not confirm equivalence of these techniques. Rather, this lack of difference is likely an indication of the granularity of our data and heterogeneity in outcomes and confounding variables reporting among studies.

Therefore, one of the major conclusions of this study is we must improve the quality of data reporting in the literature in order to improve the acceptance and validity of surgical treatment for painful neuromas. In particular, studies need to include clear descriptions of how a neuroma is diagnosed, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data about confounders such as age, ethnicity, smoking status, socio-economic status, employment status, and litigation or workers’ compensation claims. These data should include precision estimates and not just ranges. Similarly, outcomes reporting should be standardized. We suggest using a pre- and postoperative visual analogue scale in conjunction with a pain diagram and list of pain adjectives. We use a standardized pain assessment sheet at every visit (Appendix 3). It is essential that future studies collect long-term follow up data on patients and include non-biased reporting of reoperative rates and treatment failures.

CONCLUSIONS

Surgical management of painful neuromas led to clinically meaningful improvement of pain in approximately 77% of cases regardless of surgical technique employed. Although no technique proved to be clearly superior, these data demonstrate that surgical intervention should be considered in the treatment algorithm for patients suffering from painful neuroma refractory to medical management. Future studies evaluating the surgical treatment of neuroma, or those comparing surgical techniques, need to be careful to define their treatment, outcomes, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and should account for confounding variables in order to provide meaningful data and to facilitate the evidence-based treatment of our patients with painful neuromas.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1: Neuroma Study Quality of Reporting Assessment Tool. This 15 point score scale derived for the Downs and Black checklist for assessing study quality was used to rate the quality of information presented in each article included in this meta-analysis.

Appendix 3: Patient Pain Evaluation Questionnaire. This questionnaire is given to every patient in our surgical clinic at every visit to evaluate and track pre- and post-operative pain. The patient’s drawing of their pain location and their degree of pain are useful adjuncts to the physical exam in making the correct diagnosis.

Appendix 2: Symmetric distribution of log odds ratios of surgical success among studies and Peter’s test p>0.05 indicate a lack of publication bias among the 54 included studies. OR = odds ratio.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences for grant UL1 TR000448 that helped make this work possible. RPP is supported by a NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Institutional Research Training Grant (T32CA190194, PI Colditz).

Footnotes

The authors have no other financial interests or disclosures relating to this work.

References

- 1.Aasvang E, Kehlet H. Chronic postoperative pain: the case of inguinal herniorrhaphy. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95(1):69–76. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adani R, Tarallo L, Battiston B, Marcoccio I. Management of neuromas in continuity of the median nerve with the pronator quadratus muscle flap. Annals of plastic surgery. 2002;48(1):35–40. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adani R, Tos P, Tarallo L, Corain M. Treatment of painful median nerve neuromas with radial and ulnar artery perforator adipofascial flaps. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2014;39(4):721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atherton D, Elliot D. Relocation of Neuromas of the Lateral Antebrachial Cutaneous Nerve of the Forearm into the Brachialis Muscle. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2007;32(3):311–315. doi: 10.1016/J.JHSB.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atherton D, Fabre J, Anand P, Elliot D. Relocation of painful neuromas in zone III of the hand and forearm. Journal of Hand Surgery: European Volume. 2008;33(2):155–162. doi: 10.1177/1753193408087107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atherton D, Leong J, Anand P, Elliot D. Relocation Of Painful End Neuromas And Scarred Nerves From The Zone II Territory Of The Hand. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2007;32(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balcin H, Erba P, Wettstein R, Schaefer D, Pierer G, Kalbermatten D. A comparative study of two methods of surgical treatment for painful neuroma. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 2009;91(6):803–808. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B6.22145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbera J, Albert-Pamplo R. Centrocentral anastomosis of the proximal nerve stump in the treatment of painful amputation neuromas of major nerves. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1993;79(3):331–334. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.3.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bek D, Demiralp B, Komurcu M, Atesalp S. The relationship between phantom limb pain and neuroma. Acta orthopaedica et traumatologica turcica. 2006;40(1):44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourke H, Yelden K, Robinson K, Sooriakumaran S, Ward D. Is revision surgery following lower-limb amputation a worthwhile procedure? A retrospective review of 71 cases. Injury. 2011;42(7):660–666. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burchiel K, Johans T, Ochoa J. The surgical treatment of painful traumatic neuromas. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1993;78(5):714–719. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.5.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell JN. Neuroma Pain. In: Gebhart GF, Schmidt RF, editors. Encyclopedia of pain. 2. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2013. pp. 2056–2058. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cetas JS, Saedi T, Burchiel KJ. Destructive procedures for the treatment of nonmalignant pain: a structured literature review. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(3):389–404. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/109/9/0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiodo C, Miller S. Surgical treatment of superficial peroneal neuroma. Foot and Ankle International. 2004;25(10):689–694. doi: 10.1177/107110070402501001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colbert SH. Painful sequelae of Peripheral Nerve Injuries. In: M SE, editor. Nerve Surgery. New York, NY: Thieme; 2014. pp. 591–619. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellon A. Invited discussion. Annals of plastic surgery. 2002;48(2):158–160. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dellon A, Aszmann O. Treatment of superficial and deep peroneal neuromas by resection and translocation of the nerves into the anterolateral compartment. Foot and Ankle International. 1998;19(5):300–303. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dellon A, Barrett S. Sinus tarsi denervation: Clinical results. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2005;95(2):108–113. doi: 10.7547/0950108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dellon A, Kim J, Ducic I. Painful neuroma of the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm after surgery for lateral humeral epicondylitis. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2004;29(3):387–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dellon A, Mackinnon S. Treatment of the painful neuroma by neuroma resection and muscle implantation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1986;77(3):427–438. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198603000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled clinical trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devor M, Tal M. Nerve resection for the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain. Pain. 2014;155(6):1053–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorsi MJ, Chen L, Murinson BB, Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Meyer RA, Belzberg AJ. The tibial neuroma transposition (TNT) model of neuroma pain and hyperalgesia. Pain. 2008;134(3):320–334. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ducic I, Levin M, Larson E, Al-Attar A. Management of chronic leg and knee pain following surgery or trauma related to saphenous nerve and knee neuromata. Annals of plastic surgery. 2010;64(1):35–40. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31819b6c9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ducic I, Mesbahi A, Attinger C, Graw K. The role of peripheral nerve surgery in the treatment of chronic pain associated with amputation stumps. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121(3):908–914. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000299281.57480.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliot D, Lloyd M, Hazari A, Sauerland S, Anand P. Relief of the pain of neuromas-in-continuity and scarred median and ulnar nerves in the distal forearm and wrist by neurolysis, wrapping in vascularized forearm fascial flaps and adjunctive procedures. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2010;35(7):575–582. doi: 10.1177/1753193410366191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans G, Dellon A. Implantation of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve into the pronator quadratus for treatment of painful neuroma. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1994;19(2):203–206. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fisher GT, Boswick JA., Jr Neuroma formation following digital amputations. The Journal of trauma. 1983;23(2):136–142. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198302000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flor H, Nikolajsen L, Staehelin Jensen T. Phantom limb pain: a case of maladaptive CNS plasticity? Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7(11):873–881. doi: 10.1038/nrn1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friscia DA, Strom DE, Parr JW, Saltzman CL, Johnson KA. Surgical treatment for primary interdigital neuroma. Orthopedics. 1991;14(6):669–672. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19910601-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuentes J, Armijo-Olivo S, Funabashi M, Miciak M, Dick B, Warren S, Rashiq S, Magee DJ, Gross DP. Enhanced therapeutic alliance modulates pain intensity and muscle pain sensitivity in patients with chronic low back pain: an experimental controlled study. Physical therapy. 2014;94(4):477–489. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghilardi JR, Freeman KT, Jimenez-Andrade JM, Mantyh WG, Bloom AP, Kuskowski MA, Mantyh PW. Administration of a tropomyosin receptor kinase inhibitor attenuates sarcoma-induced nerve sprouting, neuroma formation and bone cancer pain. Mol Pain. 2010;6:87. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gotoda Y, Kambara N, Sakai T, Kishi Y, Kodama K, Koyama T. The morbidity, time course and predictive factors for persistent post-thoracotomy pain. European journal of pain. 2001;5(1):89–96. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenland S, O'Rourke K. On the bias produced by quality scores in meta-analysis, and a hierarchical view of proposed solutions. Biostatistics (Oxford, England) 2001;2(4):463–471. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/2.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guse D, Moran S. Outcomes of the surgical treatment of peripheral neuromas of the hand and forearm: a 25-year comparative outcome study. Annals of plastic surgery. 2013;71(6):654–658. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182583cf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hazari A, Elliot D. Treatment of end-neuromas, neuromas-in-continuity and scarred nerves of the digits by proximal relocation. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2004;29(4):338–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herbert T, Filan S. Vein implantation for treatment of painful cutaneous neuromas. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1998;23 B(2):220–224. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(98)80178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herndon J, Eaton R, Littler J. Management of painful neuromas in the hand. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 1976;58(3):369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG) American journal of industrial medicine. 1996;29(6):602–608. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunter JP, Saratzis A, Sutton AJ, Boucher RH, Sayers RD, Bown MJ. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2014;67(8):897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. Jama. 1999;282(11):1054–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kakinoki R, Ikeguchi R, Atiyya A, Nakamura T. Treatment of posttraumatic painful neuromas at the digit tip using neurovascular island flaps. The Journal of hand surgery. 2008;33(3):348–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kakinoki R, Ikeguchi R, Matsumoto T, Shimizu M, Nakamura T. Treatment of painful peripheral neuromas by vein implantation. International Orthopaedics. 2003;27(1):60–64. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0390-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kandenwein J, Richter H, Antoniadis G. Is surgery likely to be successful as a treatment for traumatic lesions of the superficial radial nerve? Nervenarzt. 2006;77(2):175–176. 179–180. doi: 10.1007/s00115-005-1993-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim J, Dellon A. Neuromas of the calcaneal nerves. Foot and Ankle International. 2001;22(11):890–894. doi: 10.1177/107110070102201106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koch H. Painful neuroma - Mid-term results of resection and nerve stump transposition into veins. European Surgery - Acta Chirurgica Austriaca. 2011;43(6):378–381. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koch H, Haas F, Hubmer M, Rappl T, Scharnagl E. Treatment of painful neuroma by resection and nerve stump transplantation into a vein. Annals of plastic surgery. 2003;51(1):45–50. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000054187.72439.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krishnan KG, Pinzer T, Schackert G. Coverage of painful peripheral nerve neuromas with vascularized soft tissue: method and results. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(2 Suppl):369–378. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000156881.10388.d8. discussion 369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krishnan KGPT, Schackert G. Coverage of painful peripheral nerve neuromas with vascularized soft tissue: Method and results. Comments. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(4 SUPPL):ONS-377–ONS-378. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000156881.10388.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laborde K, Kalisman M, Tsai T. Results of surgical treatment of painful neuromas of the hand. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1982;7(2):190–193. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(82)80086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lanzetta M, Nolli R. Nerve stripping: new treatment for neuromas of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2000;25(2):151–153. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1999.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y, Dorsi MJ, Meyer RA, Belzberg AJ. Mechanical hyperalgesia after an L5 spinal nerve lesion in the rat is not dependent on input from injured nerve fibers. Pain. 2000;85(3):493–502. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loh Y, Stanley J, Jari S, Trail I. Neuroma of the distal posterior interosseous nerve. A cause of iatrogenic wrist pain. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 1998;80(4):629–630. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b4.8478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mackinnon S, Dellon A. Results of treatment of recurrent dorsoradial wrist neuromas. Annals of plastic surgery. 1987;19(1):54–61. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198707000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL, Hudson AR, Hunter DA. Alteration of neuroma formation by manipulation of its microenvironment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76(3):345–353. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198509000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. American journal of epidemiology. 1993;138(11):923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martins R, Siqueira M, Heise C, Yeng L, De Andrade D, Teixeira M. Interdigital direct neurorrhaphy for treatment of painful neuroma due to finger amputation. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00701-014-2288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Masquelet A, Bellivet C, Nordin J. Treatment of painful neuromas of the hand by intra-osseous implantation [in French] Ann Chir Main. 1987;6:64–6. doi: 10.1016/s0753-9053(87)80012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meyer RA, Raja SN, Campbell JN, Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL. Neural activity originating from a neuroma in the baboon. Brain Res. 1985;325(1–2):255–260. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151(4):264–269. w264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nahabedian M, Johnson C. Operative management of neuromatous knee pain: patient selection and outcome. Annals of plastic surgery. 2001;46(1):15–22. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nelson AW. The painful neuroma: the regenerating axon verus the epineural sheath. The Journal of surgical research. 1977;23(3):215–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(77)90024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Statistics in medicine. 1998;17(8):857–872. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nikolajsen L, Christensen KF, Haroutiunian S. Phantom limb pain: treatment strategies. Pain management. 2013;3(6):421–424. doi: 10.2217/pmt.13.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noordenbos W, Wall P. Implications of the failure of nerve resection and graft to cure chronic pain produced by nerve lesions. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1981;44(12):1068–1073. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.12.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Novak C, Van Vliet D, Mackinnon S. Subjective outcome following surgical management of upper extremity neuromas. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1995;20(2):221–226. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Novak CB. Evaluation of the patient with nerve injury or nerve compression. In: M SE, editor. Nerve Surgery. New York, NY: Thieme; 2014. pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paterson S, Schmelz M, McGlone F, Turner G, Rukwied R. Facilitated neurotrophin release in sensitized human skin. European journal of pain (London, England) 2009;13(4):399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. Jama. 2006;295(6):676–680. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pezet S. Neurotrophins and pain. Biologie aujourd'hui. 2014;208(1):21–29. doi: 10.1051/jbio/2014002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rajput K, Reddy S, Shankar H. Painful neuromas. The Clinical journal of pain. 2012;28(7):639–645. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31823d30a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D. Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors. Proceedings Biological sciences / The Royal Society. 1996;263(1369):377–386. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reisman N, Dellon A. The abductor digiti minimi muscle flap: A salvage technique for palmar wrist pain. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1983;72(6):859–863. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198312000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rose J, Belsky M, Millender L, Feldon P. Intrinsic muscle flaps: the treatment of painful neuromas in continuity. The Journal of hand surgery. 1996;21(4):671–674. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(96)80024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sarris I, Gobel F, Gainer M, Vardakas D, Vogt M, Sotereanos D. Medial brachial and antebrachial cutaneous nerve injuries: Effect on outcome in revision cubital tunnel surgery. Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery. 2002;18(8):665–670. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sehirlioglu A, Ozturk C, Yazicioglu K, Tugcu I, Yilmaz B, Goktepe A. Painful neuroma requiring surgical excision after lower limb amputation caused by landmine explosions. International Orthopaedics. 2009;33(2):533–536. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0466-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sheth RN, Dorsi MJ, Li Y, Murinson BB, Belzberg AJ, Griffin JW, Meyer RA. Mechanical hyperalgesia after an L5 ventral rhizotomy or an L5 ganglionectomy in the rat. Pain. 2002;96(1–2):63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00429-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Souza J, Nystrom A, Dumanian G. Patient-guided peripheral nerve exploration for the management of chronic localized pain. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(1):221–225. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318221dc12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Spauwen P, Hartman E. Reverse fasciocutaneous forearm flaps are effective in treating incapacitating neuromas in the hand. European Journal of Plastic Surgery. 1999;22(2–3):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stahl S, Goldberg J. The use of vein grafts in upper extremity nerve surgery. European Journal of Plastic Surgery. 1999;22(5–6):255–259. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stahl S, Rosenberg N. Surgical treatment of painful neuroma in medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Annals of plastic surgery. 2002;48(2):154–158. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stokvis A, van der Avoort D, van Neck J, Hovius S, Coert J. Surgical management of neuroma pain: a prospective follow-up study. Pain. 2010;151(3):862–869. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tennent T, Birch N, Holmes M, Birch R, Goddard N. Knee pain and the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1998;91(11):573–575. doi: 10.1177/014107689809101106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thomas M, Stirrat A, Birch R, Glasby M. Freeze-thawed muscle grafting for painful cutaneous neuromas. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - Series B. 1994;76(3):474–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thomsen L, Bellemere P, Loubersac T, Gaisne E, Poirier P, Chaise F. Treatment by collagen conduit of painful post-traumatic neuromas of the sensitive digital nerve: A retrospective study of 10 cases. Chirurgie de la Main. 2010;29(4):255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tung TH, Mackinnon SE. Secondary carpal tunnel surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(7):1830–1843. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-49008-1_40. quiz 1844,1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tupper J, Booth D. Treatment of painful neuromas of sensory nerves in the hand: a comparison of traditional and newer methods. The Journal of hand surgery. 1976;1(2):144–151. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(76)80008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Upton AR, McComas AJ. The double crush in nerve entrapment syndromes. Lancet. 1973;2(7825):359–362. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)93196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vaienti L, Merle M, Battiston B, Villani F, Gazzola R. Perineural fat grafting in the treatment of painful end-neuromas of the upper limb: a pilot study. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2013;38(1):36–42. doi: 10.1177/1753193412441122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Watson J, Gonzalez M, Romero A, Kerns J. Neuromas of the Hand and Upper Extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(3):499–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Whipple RR, Unsell RS. Treatment of painful neuromas. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 1988;19(1):175–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wilbourn AJ, Gilliatt RW. Double-crush syndrome: a critical analysis. Neurology. 1997;49(1):21–29. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yan H, Gao W, Pan Z, Zhang F, Fan C. The expression of alpha-SMA in the painful traumatic neuroma: potential role in the pathobiology of neuropathic pain. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(18):2791–2797. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yan H, Zhang F, Kolkin J, Wang C, Xia Z, Fan C. Mechanisms of nerve capping technique in prevention of painful neuroma formation. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e93973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Neuroma Study Quality of Reporting Assessment Tool. This 15 point score scale derived for the Downs and Black checklist for assessing study quality was used to rate the quality of information presented in each article included in this meta-analysis.

Appendix 3: Patient Pain Evaluation Questionnaire. This questionnaire is given to every patient in our surgical clinic at every visit to evaluate and track pre- and post-operative pain. The patient’s drawing of their pain location and their degree of pain are useful adjuncts to the physical exam in making the correct diagnosis.

Appendix 2: Symmetric distribution of log odds ratios of surgical success among studies and Peter’s test p>0.05 indicate a lack of publication bias among the 54 included studies. OR = odds ratio.