Abstract

Objective

We examined associations of residential distance to major roadways, as a proxy for traffic-related air pollution exposures, with sperm characteristics and male reproductive hormones.

Design

The cohort included 797 men recruited from Massachusetts General Hospital Fertility Center between 2000 and 2015 to participate in fertility research studies.

Materials and Methods

Men reported their residential addresses at enrollment and provided 1–6 semen samples and a blood sample during follow-up. We estimated the Euclidean distance to major roadways (e.g. interstates and highways: limited access highways, multi–lane highways (not limited access), other numbered routes, and major roads) using information from the Massachusetts Department of Geographic Information Systems. Semen parameters (1,238 semen samples), sperm DNA integrity (389 semen samples), chromosomal disomy (101 semen samples), and serum reproductive hormones (405 serum samples) were assessed following standard procedures.

Results

Men in this cohort were primarily Caucasian (86%), not current smokers (92%), with a college or higher education (88%), and had an average age of 36 years and BMI of 27.7 kg/m2. The median (interquartile range) residential distance to a major roadway was 111 (37, 248) meters. Residential proximity to major roadways was not associated with semen parameters, sperm DNA integrity, chromosomal disomy, or serum reproductive hormone concentrations. The adjusted percent change (95% CI) in semen quality parameters associated with a 500 meter increase in residential distance to a major roadway was −1.0% (−6.3, 4.5) for semen volume, 4.3% (−5.8, 15.7) for sperm concentration, 3.1% (−7.2, 14.5) for sperm count, 1.1% (−1.2, 3.4) for % total motile sperm, and 0.1% (−0.3, 0.5) for % morphologically normal sperm. Results were consistent when we modeled the semen parameters dichotomized according to WHO 2010 reference values.

Conclusion

Residential distance to major roadways, as a proxy for traffic-related air pollution exposure, was not related to sperm characteristics or serum reproductive hormones among men attending a fertility clinic in Massachusetts.

Key terms: proximity, road, air pollution, men, infertility, semen, reproductive hormone, DNA integrity, disomy

Introduction

One in six couples trying to conceive experience infertility(Louis et al., 2013; Thoma et al., 2013) and male factors, such as abnormalities in semen quality parameters, are identified in approximately 40% of these couples(Legare et al., 2014). A meta–analysis of over 185 studies has shown that sperm counts have declined in Western countries by 50–60% from 1973–2011(Levine et al., 2017). While there is still continued debate centered on the reasons for this decline, there is growing evidence that increasing exposure to environmental chemicals, such as air pollution, could be driving this downward trend.

Several animal studies have demonstrated that air pollution, particularly due to diesel exhaust, has harmful effects on sperm quality including decreased production of spermatozoa and increased sperm DNA damage (Ema et al., 2013; Jedlinska-Krakowska et al., 2006). Other animal studies have also observed structural changes in Leydig cells, a reduction in the number of Sertoli cells, decreases in testosterone concentrations, and increases in luteinizing hormone (LH) concentrations after exposure to diesel exhaust(Kubo-Irie et al., 2011; Takeda et al., 2004; Tsukue et al., 2001).

In humans, there is some literature on this subject, but the existing studies are difficult to compare due to the heterogeneity of air pollutants under study and the differing methodologies utilized in terms of study populations, outcome assessment, and duration and period of exposure. In a recent review of the literature(Lafuente et al., 2016), all but 1 of the 17 articles found significant alterations in at least one of the sperm parameters studied in association with at least one of the pollutants; however the findings were not always consistent across studies. Thus, the authors concluded that there was some evidence of an effect of outdoor air pollution on semen quality parameters, particularly in regards to sperm DNA fragmentation and sperm morphology, yet more research was needed.

Because diesel exposure might be particularly detrimental to reproductive health, proximity to traffic as an exposure metric might better capture exposure to diesel (and other car exhausts) as compared to specific pollutants which can come from many sources (e.g. fine and course particulate matter) and vary from region to region. Proximity to major roadways also captures a variety of traffic-related air pollutants in addition to other associated exposures such as traffic-related noise compared to a single pollutant approach. However, only one study to date has assessed traffic proximity in relation to semen quality parameters(Wijesekara et al., 2015). Specifically, Wijesekara and colleagues(Wijesekara et al., 2015), compared Sri Lankan men who lived less than 50m from a main road or who worked in an industry emanating toxicants to unexposed men and found that exposed men had lower sperm concentrations, progressive motility, and normal morphology. However, their analysis did not differentiate between occupational and environmental exposure to a variety of toxicants, nor was traffic proximity the main focus of the study.

To address this research gap, we evaluated the association between traffic-related air pollution, as measured by residential proximity to major roadways, and markers of male fertility including sperm characteristics and serum reproductive hormone concentrations in a large sample of men attending a fertility clinic in the United States between 2000 and 2015. We hypothesized that men residing closer to major roadways would have impaired sperm characteristics and altered serum reproductive hormones.

Methods

Participants

Men without a history of vasectomy who presented for evaluation at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Fertility Center were invited to participate between 2000 and 2015 in two fertility research studies. The Semen Quality Study (SQS) (2000 to 2004) and the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study (2004 to 2015). The latter is a continuation of the SQS study that was expanded to include female participants. All men were recruited from the fertility center at the MGH and they were all part of couples seeking infertility treatment. Of the eligible men, approximately 60% agreed to participate. All men signed an informed consent after the study procedures were explained by a research nurse. Men self-reported their demographics and medical history in questionnaires and the research nurse measured their height and weight at time of enrollment and collected some information from medical records. Research studies were approved by institutional review boards at MGH and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

Of the total 928 men recruited, 26 azoospermic men were excluded to prevent undue influence from extreme sperm counts and because the mechanism responsible for azoospermia may be related to obstructive or genetic causes rather than environmental factors. Out of the 902 remaining men, we further excluded 105 men who lived outside Massachusetts (for whom residential roadway proximity was not available). The remaining 797 men contributed a total of 1,238 semen samples between 2000 and 2015 (Supplemental Figure 1). Of the 797 men, a subset of 389 semen samples (49%) from men enrolled between 2000 and 2004were previously analyzed for sperm DNA damage and 405 serum samples (51%) were analyzed for reproductive hormones. A further 101 semen samples (13%) collected between 2000 and 2011 were analyzed for sperm aneuploidy. To address the possibility of selection bias in our subanalyses, we compared the baseline characteristics and proximity to major roadways between men with available measures of sperm DNA damage, hormones, and sperm aneuploidy with those without these measures.

Roadway Proximity

Upon enrollment, men provided their residential address for reimbursement purposes. We then geocoded the addresses and determined the Euclidian distance (in meters) to the nearest major roadway using Geographical Information System (GIS) software (ArcGIS 10.2, ESRI, Redlands, CA). The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) roadway dataset contains all of the public and the majority of the private roadways in Massachusetts, including designations for interstates and highways. MassGIS classifies the following as major roadways: limited access highways, multi–lane highways (not limited access), other numbered routes, and major roads that are arterials and collectors. This dataset was updated through December 31, 2013 and was released by MassGIS on June 13, 2014.

Semen analysis

At recruitment and at each subsequent visit, men provided a semen sample on–site by masturbation at the MGH andrology laboratory into a sterile plastic specimen cup. Men were asked to abstain from ejaculation for 2–5 days before providing semen samples. Men reported the duration of ejaculation abstinence prior to providing the specimen. All semen samples were analyzed using standardized clinical protocols and quality control as described previously (Nassan et al., 2016). Briefly, after collection, the sample was liquefied at 37°C for 20 minutes before analysis. The physical properties of the semen were reported, including the sample volume, color, pH and viscosity. Ejaculate volume was measured using a graduated serological pipet. Sperm concentration and motility were assessed with a computer–aided semen analysis (CASA; 10HTM–IVOS, Hamilton–Thorne Research, Beverly, MA)(WHO, 2010). Sperm morphology was measured on two slides for each specimen (with at least 200 cells assessed per slide). Sperm morphology was assessed using Kruger’s strict criteria(Kruger et al., 1988).

Sperm DNA integrity

The neutral comet assay was used following a previously described protocol (Duty et al., 2003). Briefly, 50μL of a semen/agarose mixture was embedded between two additional layers of agarose on microgel electrophoresis glass slides. Then, slides were immersed in a cold lysing solution to dissolve the sperm cell membranes and make sperm chromatin available. After one hour of cold lysis, slides were transferred to a solution for enzyme treatment with RNAse (Amresco, Solon, OH) and incubated for four hours at 37°C. Slides were transferred to a second enzyme treatment with proteinase K (Amresco) and incubated for 18 hours at 37°C and placed on a horizontal slab in an electrophoretic unit and underwent electrophoresis for one hour. DNA in the gel was subsequently precipitated, fixed in ethanol and dried. Slides were stained and observed with a fluorescence microscope.

Comet extent (CE), DNA % in the tail (%tail) and tail distributed moment (TDM) were measured in 100 sperm cells in each semen sample using the VisComet software (Impulus Computergestutze Bildanalyse GmbH, Gilching, Germany). CE represents the average total comet length from the beginning of the head to the last visible pixel in the tail. The average proportion of DNA that is in the tail of the comet is represented by %Tail. TDM represents an integrated value that takes into account the distance and intensity of comet fragments(Chavarro et al., 2010). TDM= Σ(I×X)ΣI, where ΣI is the sum of all intensity values for the head, body or tail, and X is the x–position of the intensity value. The number of cells >300μm i.e., too long to measure with VisComet, were counted for each manand used as an additional measure of sperm DNA damage.

Sperm disomy

Sperm fluorescence in–situhybridization (FISH) analysis was performed. The procedures for this analysis have been described in detail previously(McAuliffe et al., 2012; Perry et al., 2011). Briefly, for chromosomes X, Y, and 18 (autosomal control), FISH was performed with a series of nonoverlapping field images taken for each prepared FISH slide using a fluorescence laser scanning wide–field microscope. Custom MATLAB software, designed to utilize scoring criteria for size and shape scored the images using strict scoring criteria(Baumgartner et al., 1999). The software identified sperm nuclei and the number of signals contained therein through a colocalization analysis.

Reproductive Hormones

A non–fasting blood sample was drawn on the same day of the initial semen sample. Blood was centrifuged, and serum was stored at −80°C until analysis. Serum was thawed and analyzed for follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), LH, inhibin–B, prolactin, estradiol, total testosterone, and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG).

LH, FSH, estradiol and prolactin concentrations were determined by microparticle enzyme immunoassay using an automated Abbot AxSYM system (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). The Second International Reference Preparation (WHO 71/223) was used as the reference standard. The assay sensitivities were 1.2 IU/L for LH and 1.1 IU/L for FSH. The intra–assay coefficient of variation (CV) for LH and FSH was < 3% and < 5%, respectively. The assay sensitivity for estradiol was 20 pg/mL with a within–run CV between 3% and 11%, and the total CV was between 5% and 15%. For prolactin, the assay sensitivity was 0.6ng/mL, the within–run CV was ≤3% and total CV ≤6%. Total testosterone was measured directly using the Coat–A–Count RIA kit (Diagnostic Products, Los Angeles, CA), which has a sensitivity of 4ng/dL, and inter–assay CV of 12% and an intra–assay CV of 10%. SHBG was measured using an automated system (Immulite; DPC Inc, Los Angeles, CA), which uses a solid–phase two–site chemiluminescent enzyme immunometric assay and has an inter–assay CV of less than 8%. Inhibin B was measured using a double–antibody, enzyme–linked immunosorbent assay (Oxford Bioinnovation, Oxford, United Kingdom) with inter–assay CV of 20% and intra–assay CV of 8%. The testosterone to LH ratio, a measure of Leydig cell function, was calculated by dividing total testosterone (nmol/L) by LH (IU/L).

Statistical analysis

Based on the observed distribution of residential distance to major roadways in our study and due to the known exponential decay of traffic-related pollution with distance(Dorans et al., 2017; Hart et al., 2014; Karner et al., 2010), we categorized exposure into the following categories: <50m, 50–99m, 100–199, 200–399m and ≥400m (reference group). We also assessed distance to major roadways as a continuous exposure. We calculated descriptive statistics for baseline and time–varying characteristics across categories of roadway proximity and tested for differences across categories using Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables.

We examined the distributions of each sperm and hormone parameter in our population to determine if transformation of the outcome was necessary before statistical analysis. After such examination, we natural-log transformed ejaculate volume, sperm concentration, total sperm count, total motile sperm count, morphologically normal count, percent DNA in tail, and all the serum hormones except testosterone and SHBG. We assessed non-linearity of the association between the distance to major road with a smoothing function and the continuous outcomes by fitting generalized additive mixed models (GAMM) with penalized splines using a cross-validation method (Ding et al., 2016). The GAMM adjusted for the same covariate as in the final model including race, age, sexual abstinence time and socioeconomic status as measured by the census tract median family income in the past year. The parameters of the smoothing curve were estimated by penalized least squares. The within-person correlation was accounted for by assuming random intercepts between persons. Because of the generally linear associations, we used linear mixed effect regression models with a random intercept as our final models. For serum hormones and sperm DNA fragmentation measures we used linear regression models. Poisson regression was used to model the number of aneuploidy sperm and of cells with high DNA damage with the natural-log of the number of counted sperm as the offset variable. All results are presented as estimated marginal means in each exposure category (back–transformed to the original scale when necessary, with all continuous covariates set to their mean levels and all categorical set to their weighted average level). We also present results for the continuous distance metric analysis as the absolute change (non–transformed outcomes) or percent change (transformed outcomes) in the outcome for a 500m increase in distance from major roadway. As an additional analysis, we dichotomized semen parameters according to the WHO lower reference limits(WHO, 2010), where applicable, and estimated odds ratios (ORs) using generalized linear mixed models with a random intercept, binary outcome, and logit link function. Covariates were identified based on a prior knowledge using directed acyclic graphs and on their statistical basis(Weng et al., 2009). The final model adjusted for race, age, sexual abstinence time and socioeconomic status as measured by the census tract median family income in the past year (in 2011 inflation–adjusted dollars) according to the American Community Survey 2007–2010. In the disomy models, we further adjusted for sperm motility, morphology, and log concentration.

In sensitivity analyses, we conducted the semen quality analysis after restricting the data to one sample per man (797 samples). We also explored different cut points for the categories of distance to major roads e.g., <200m, 200–499m, 500–999, and ≥1000m and others. We conducted a sensitivity analysis after excluding men with a history of reproductive diseases (including groin injury, undescended testes, varicocele, testicular torsion, testicular injury, hernia, epididymitis, prostatitis or seminal vesicle infection). We also further adjusted our multivariable models for BMI, education, reproductive diseases, season, and calendar year to assess the robustness of our results. We conducted all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and considered two–sided p-values <0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

Men had an average (standard deviation, SD) age of 36.3 (5.3) years and BMI of 27.7 (4.7) kg/m2. The majority were Caucasian (86%), had college degree or higher (88%), and were not current smokers (92%). Of the 797 men in our study, 580 (73%) provided one semen sample, 113 (14%) gave 2 samples, 50 (6%) gave 3 samples, and 54 (7%) gave ≥ 4 samples. The average (SD) time elapsed between semen collection and analysis was 23.1 (5.81) minutes and 82% of the men had sexual abstinence times of ≥2 days (Table 1). For those who provided more than one semen sample, the median (interquartile range) of the time elapsed between two semen samples was 82 (86) days. The differences in demographic characteristics across categories of residential distance to major roadways were small and not statistically significant except for race, education, census tract median income, and abstinence time (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and semen sample characteristics among 797 men (1,238 semen samples) in our study cohort (2000–2015).

| Baseline Characteristics (797 men) | N (%) or mean (SD)1 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 36.3 (5.28) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.7 (4.73) |

| BMI categories | |

| <25 kg/m2 | 225 (28.2) |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 380 (47.7) |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 192 (24.1) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 685 (86.0) |

| African American | 27 (3.39) |

| Asian | 43 (5.40) |

| Other | 42 (5.27) |

| Census Tract Median Income2, $ | 106,258 (43,050) |

| Education categories | |

| Less than college | 95 (11.9) |

| College degree | 409 (51.3) |

| Graduate degree | 293 (36.8) |

| Reproductive diseases,3 | 255 (32.0) |

| Reproductive surgeries4 | 82 (10.3) |

| Current smoking | 60 (7.53) |

| Semen Sample Characteristics (1,238 semen samples) | |

| Collected April through September | 618 (49.9) |

| Time between semen collection and analysis, mins | 23.1 (5.81) |

| Sexual abstinence time | |

| <2 days | 225 (18.2) |

| 2–3 days | 487 (39.3) |

| 3–4 days | 255 (20.6) |

| >4 days | 271 (21.9) |

Abbreviations: BMI; body mass index, mins; minutes.

N (%) is presented for categorical/binary variables and mean (SD) is presented for continuous variables.

Median family income in the past 12 months (in 2011 inflation-adjusted dollars) by tract from the American Community Survey 2007–2010 estimates.

Groin injury, testes not always in scrotum, varicocele, testicular torsion, testicular injury, hernia, epididymitis, prostatitis and seminal vesicle infection.

Varicocelectomy, orchidopexy, hydrocelectomy, repair of hernia, urethera, or hypospadias, sympahthectomy or bladder neck surgery.

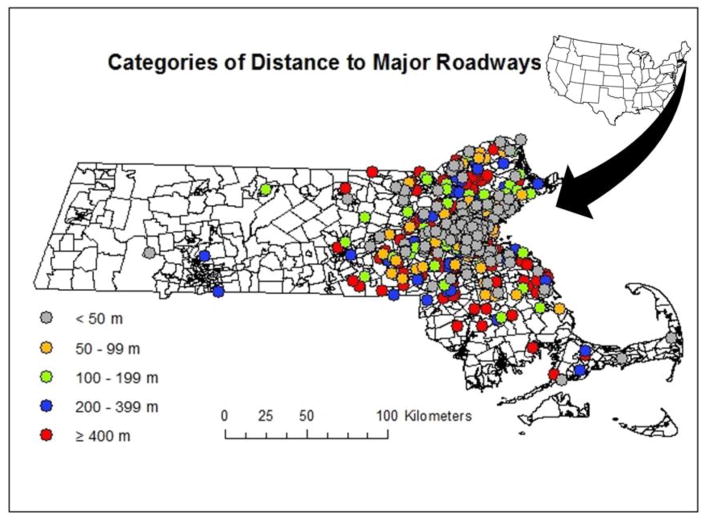

The median (interquartile range) residential distance to a major roadway was–111 (37, 248) meters and ranged between 1 and 3422 m. The geographic distribution of residential proximity to major roadways is shown in Figure 1. Men who we had available measures for sperm DNA damage, hormone, and sperm aneuploidy were not different from men who did not (Supplementary Table 2). A summary of the semen quality, DNA integrity, sperm disomy and serum reproductive hormone parameters in our population is presented in Table 2. About half (53%) of the semen samples provided by the men in our study had >39 million total sperm, >40% motile sperm, and >4% morphologically normal sperm.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of residential distance to nearest major roadways for men in our cohorts.

Table 2.

Semen parameters and hormone concentration distributions for continuous outcomes and n (%) for the binary outcomes below the WHO reference values.

| Semen Parameters | Mean (SD), [Range] | Median (IQR) | (5th, 95th percentile) | Samples (n) | n (%) below WHO Lower Reference Limits1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejaculate volume (ml) | 2.95 (1.47), [0.10,11.0] | 2.70 (1.90) | (1.00,5.50) | 1238 | 182 (15) |

| Sperm Concentration (million/mL) | 86.0 (84.6), [1.20,889] | 63.6 (88.7) | (9.60,232) | 1238 | 116 (9) |

| Total sperm count (million) | 230 (239), [1.54,2690] | 161 (230) | (26.5,628) | 1238 | 117 (9) |

| Sperm Motility (%Total) | 47.5 (22.6), [0,97.0] | 48.9 (36.7) | (10.0,82.0) | 1238 | 468 (38) |

| Sperm Motility (%Progressive) | 28.3 (15.4), [0,83.0] | 27.3 (23.9) | (4.37,54.0) | 1238 | 738 (60) |

| Motile count (million) | 133 (171), [0,1972] | 76.3 (152) | (3.28,448) | 1238 | - |

| Sperm Morphology (% normal) | 6.77 (3.93), [0,23.0] | 6.00 (5.00) | (1.00,14.0) | 1238 | 300 (24) |

| Morphologically Normal count (million) | 18.0 (24.9), [0,308] | 9.98 (20.0) | (0.47,65.0) | 1238 | - |

| Good semen quality2 | - | - | - | - | 658 (53) |

| Sperm DNA Damage | |||||

| Comet extent (μm) | 131 (37.5), [53.4,249] | 130 (47.6) | (73.4,198) | 389 | - |

| Comet Tail DNA (%) | 32.1 (15.3), [6.98,82.9] | 27.2 (23.6) | (13.9,61.6) | 389 | - |

| Comet Tail distributed moment (μm) | 57.9 (14.7), [25.7,107] | 56.9 (19.5) | (35.3,85.0) | 389 | - |

| Comet Cells with high DNA damage (n) | 8.75 (12.3), [0,95.0] | 4.00 (10) | (0,33) | 389 | - |

| Hormone Concentrations | |||||

| FSH, IU/L | 8.77(5.59), [1.14,41.8] | 7.39(4.60) | (3.42,17.9) | 405 | - |

| LH, IU/L | 10.7(5.02), [0.85,47.5] | 9.71(5.98) | (4.56,19.2) | 405 | - |

| Total Testosterone/LH Ratio | 1.63(1.14), [0.36,14.6] | 1.45(0.81) | (0.63,2.84) | 405 | - |

| Inhibin-B, pg/mL | 168(73.2), [7.80,702] | 160 (77.4) | (70.5,283) | 405 | - |

| Prolactin, ng/mL | 12.9(6.63), [3.11,52.2] | 11.4(7.50) | (5.67,24.2) | 405 | - |

| Estradiol, pg/mL | 29.71(12.2), [10.0,71.0] | 30.0(14.0) | (10.0,49.0) | 405 | - |

| Total Testosterone, ng/dL | 424(140), [44.5,942] | 409(178) | (226,675) | 405 | - |

| Free Androgen Index (FAI) | 57.3(23.1), [10.1,218] | 52.7(24.7) | (31.5,94.7) | 405 | - |

| SHBG, nmol/L | 28.3(11.7), [6.50,65.8] | 26.2(14.2) | (11.9,49.9) | 405 | - |

| Nuclei scored (n) and % disomy | |||||

| Nuclei (n) | 4243 (3292), [62,18874] | 3759 (4148) | (276,11160) | 101 | - |

| X18 (%) | 27.6 (11.6), [0.39,46.6] | 28.9 (14.27) | (4.09,42.1) | 101 | - |

| Y18 (%) | 25.9 (11.7), [0.36,47.5] | 27.2 (13.34) | (2.82,41.9) | 101 | - |

| XX18 (%) | 0.48 (0.80), [0,6.17] | 0.22 (0.52) | (0,1.89) | 101 | - |

| YY18 (%) | 0.48 (0.38), [0,1.83] | 0.39 (0.43) | (0,1.28) | 101 | - |

| XY18 (%) | 0.92 (2.29), [0,17.5] | 0.38 (0.52) | (0,3.59) | 96 | - |

| Total disomy (%) | 1.84 (2.95), [0,23.9] | 1.21 (0.87) | (0.03,5.23) | 101 | - |

Abbreviations: SD; standard deviation, n; number of samples, WHO; World health organization, FSH; Follicle Stimulating Hormone, LH; Luteinizing Hormone, FAI; Free Androgen Index, and SHBG; Sex hormone-binding globulin.

WHO lower reference limits (2010)53: ejaculate volume<1.5 ml; sperm concentration <15 million/ml; total sperm count< 39 million; total motile sperm<40%; progressive motile sperm<32%, and normal sperm morphology< 4% using “strict” Tygerberg method.

Good semen quality: If a semen sample has total sperm count>39million&sperm motility>40%& morphologically normal sperm>4%.

In the unadjusted (Supplementary Table 3 & 4) and the adjusted analyses (Table 3 & 4), residential proximity to major roadways was not associated with semen parameters, DNA fragmentation, sperm disomy, or serum reproductive hormones. The adjusted % change (95% CI) in semen quality parameters associated with a 500 meter increase in residential distance to a major roadway was −1.0% (−6.3, 4.5) for semen volume, 4.3% (−5.8, 15.7) for sperm concentration, 3.1% (−7.2, 14.5) for sperm count, 1.1% (−1.2, 3.4) for % total motile sperm, and 0.1% (−0.3, 0.5) for % morphologically normal sperm. Results were consistently null when we categorized the distance to major roads and when we dichotomized the semen parameters according to WHO 2010 lower reference values. The adjusted change (95% CI) with a 500 meter increase in residential distance to a major roadway for the sperm DNA integrity parameters was −1.88% (−6.02, 2.44) for CE, −2.98% (−9.29, 3.77) for % tail, −0.31 μm (−2.43, 1.81) for TDM and −5 (−18, 16) for the number of sperm cells with high DNA damage.

Table 3.

Adjusted associations between distance from residential address to nearest major roadway and semen quality parameters and serum reproductive hormone concentrations.

| Categories of Distance to Nearest Major Roadway | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted means (95% CI)1 | <50 m | 50–99 m | 100–199 m | 200–399 m | ≥400 m | P for trend | Adjusted change per 500m increase (95% CI)2 |

| Semen Quality Parameters (797 men/1238 samples) | 244 men / 354 semen samples | 126 men / 202 semen samples | 185 men / 310 semen samples | 125 men / 200 semen samples | 117 men / 172 semen samples | ||

| Ejaculate Volume (mL) | 2.60 (2.43, 2.78) | 2.53 (2.31, 2.77) | 2.65 (2.46, 2.86) | 2.63 (2.39, 2.88) | 2.45 (2.23, 2.70) | 0.38 | −1.00 (−6.29, 4.50) |

| Sperm Concentration (million/mL) | 58.9 (51.8, 67.1) | 56.5 (47.2, 67.5) | 57.8 (49.9, 67.0) | 50.3 (42.0, 60.2) | 69.3 (57.5, 83.7) | 0.20 | 4.29 (−5.82, 15.7) |

| Total Sperm Count (million) | 153 (134, 174) | 143 (120, 171) | 153 (132, 178) | 132 (110, 158) | 169 (140, 205) | 0.44 | 3.10 (−7.23, 14.5) |

| % Total Sperm Motility | 48.3 (45.5, 51.2) | 45.5 (41.6, 49.3) | 46.6 (43.5, 49.8) | 48.0 (44.1, 51.9) | 49.8 (45.7, 53.9) | 0.33 | 1.09 (−1.16, 3.35) |

| % Progressive Sperm Motility | 29.3 (27.4, 31.2) | 28.0 (25.3, 30.6) | 27.7 (25.5, 29.9) | 29.7 (27.1, 32.4) | 30.0 (27.2, 32.8) | 0.39 | 0.63 (−0.92, 2.17) |

| Motile Sperm Count (million) | 66.9 (55.8, 80.3) | 56.5 (43.9, 72.6) | 61.4 (49.9, 75.5) | 52.7 (40.9, 67.9) | 75.9 (58.2, 98.7) | 0.39 | 5.28 (−9.06, 21.6) |

| % Normal Sperm Morphology | 7.56 (7.06, 8.06) | 6.46 (5.77, 7.14) | 6.49 (5.93, 7.05) | 6.63 (5.94, 7.32) | 6.93 (6.20, 7.65) | 0.43 | 0.11 (−0.29, 0.51) |

| Morphologically Normal Sperm Count | 10.9 (9.28, 12.8) | 9.1 (7.27, 11.35) | 9.12 (7.58, 11.0) | 8.24 (6.55, 10.3) | 11.1 (8.83, 14.0) | 0.96 | 4.66 (−6.76, 17.6) |

| Sperm DNA Damage (389 men/389 samples) | 123 men / 123 semen samples | 55 men / 55 semen samples | 80 men / 80 semen samples | 60 men / 60 semen samples | 71 men / 71 semen samples | ||

| Comet Extent (μm) | 128(119, 137) | 129(117, 141) | 128(119, 139) | 131(120, 144) | 122(113, 133) | 0.34 | −1.88(−6.02, 2.44) |

| Comet Tail DNA (%) | 29.2 (26.1, 32.7) | 26.6 (23.1, 30.7) | 28.0 (24.7, 31.6) | 28.6 (24.8, 33.0) | 27.3 (23.9, 31.1) | 0.52 | −2.98 (−9.29, 3.77) |

| Comet Tail Distributed Moment (μm) | 57.2 (53.6, 60.7) | 59.4 (54.9, 63.9) | 58.0 (54.1, 61.9) | 59.3 (54.8, 63.8) | 56.2 (52.1, 60.3) | 0.52 | −0.31 (−2.43, 1.81) |

| Comet Cells with high DNA damage (n) | 8 (6, 10) | 9 (6, 13) | 8 (5, 10) | 9 (6, 13) | 8 (5, 11) | 0.97 | −4.88 (−18.1, 16.2) |

| Reproductive Hormones (405 men/405 samples) | 129 men / 129 serum samples | 58 men / 58 serum samples | 83 men / 83 serum samples | 62 men / 62 serum samples | 73 men / 73 serum samples | ||

| Estradiol, pg/mL | 26.5 (23.4, 30.0) | 30.4 (26.2, 35.3) | 24.9 (21.9, 28.4) | 28.0 (24.0, 32.6) | 27.5 (23.9, 31.6) | 0.74 | −0.10 (−6.68, 6.96) |

| Testosterone, ng/dL | 432 (397, 466) | 479 (437, 520.4) | 382 (345, 418) | 409 (367, 452) | 414 (375, 453) | 0.28 | −2.22 (−21.4, 17.0) |

| FAI | 53.4 (48.9, 58.4) | 51.0 (45.8, 56.8) | 52.9 (48.2, 58.2) | 52.6 (47.2, 58.7) | 56.1 (50.8, 62.1) | 0.24 | 4.86 (−0.10, 10.1) |

| SHBG, nmol/L | 28.5 (25.7, 31.4) | 32.9 (29.4, 36.4) | 25.7 (22.7, 28.8) | 27.8 (24.3, 31.3) | 26.3 (23.0, 29.5) | 0.09 | −1.37 (−2.97, 0.22) |

| FSH, IU/L | 6.28 (5.54, 7.13) | 6.74 (5.78, 7.86) | 7.23 (6.32, 8.27) | 6.93 (5.92, 8.10) | 6.37 (5.52, 7.35) | 0.80 | −0.26 (−6.99, 6.97) |

| LH, IU/L | 9.52 (8.47, 10.7) | 10.7 (9.27, 12.3) | 9.46 (8.35, 10.7) | 9.69 (8.38, 11.2) | 9.48 (8.3, 10.83) | 0.68 | 0.39 (−5.89, 7.08) |

| T/LH Ratio | 1.48 (1.32, 1.67) | 1.49 (1.29, 1.72) | 1.34 (1.18, 1.52) | 1.39 (1.20, 1.61) | 1.46 (1.27, 1.66) | 0.90 | −0.42 (−6.69, 6.27) |

| Inhibin-B, pg/mL | 184 (164, 206) | 175 (152, 201) | 161 (143, 182) | 151 (131, 174) | 178 (156, 203) | 0.76 | 1.20 (−5.06, 7.88) |

| Prolactin, ng/mL | 11.0 (9.80, 12.3) | 10.9 (9.50, 12.5) | 11.2 (9.90, 12.6) | 10.0 (8.70, 11.5) | 11.7 (10.3, 13.3) | 0.45 | 0.67 (−5.44, 7.17) |

Abbreviations: CI; confidence interval, m; meter, P; p value, n; number, FSH; Follicle Stimulating Hormone, LH; Luteinizing Hormone, FAI; Free Androgen Index, and SHBG; Sex hormone-binding globulin.

Adjusted means were estimated using linear mixed models for the semen quality parameters and linear regression models for the reproductive hormone concentrations. All models were adjusted for age, race, abstinence time, and census tract median income.

All changes for hormones are presented as % change except for testosterone and SHBG as mean difference.

Table 4.

Adjusted associations between distance from residential address to nearest major roadway and sperm disomy parameters in men from 101 men (101 semen samples).

| Distance to Nearest Major Roadway | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted IRR1 of chromosol disomy (95% CI) | <50 m | 50–99 m | 100–199 m | 200–399 m | ≥400 m | P for trend | Adjusted IRR of chromosol disomy per 500 m increase (95% CI) |

| 101 men/101 samples | n=29 | n=19 | n=21 | n=10 | n=22 | ||

| XX18 | 0.05 (0, 35.9) | 1.08 (0.58, 2.00) | 0.98 (0.47, 2.04) | 0.60 (0.27, 1.37) | Ref | 0.99 | 0.93 (0.71, 1.22) |

| YY18 | 0.89 (0.60, 1.30) | 0.94 (0.59, 1.50) | 1.14 (0.73, 1.77) | 1.26 (0.77, 2.08) | Ref | 0.56 | 0.96 (0.84, 1.10) |

| XY18 | 0.49 (0.25, 0.98) | 0.67 (0.31, 1.47) | 0.70 (0.31, 1.59) | 0.31 (0.10, 0.93) | Ref | 0.16 | 1.08 (0.85, 1.37) |

| Total disomy | 0.74 (0.48, 1.15) | 0.85 (0.51, 1.43) | 0.80 (0.47, 1.37) | 0.75 (0.41, 1.38) | Ref | 0.3 | 1.01 (0.86, 1.18) |

Abbreviations: CI; confidence interval, m; meter, n; number of samples, P; p value.

Models adjusted for age, race, abstinence time, census tract median income, sperm concentration (million/mL), sperm motility (%total), and sperm morphology (% normal).

IRR: incidence rate of chromosol dismoy by distance categories compared to incidence in the reference category (≥400 m).

The corresponding adjusted % change (95% CI) for serum reproductive hormone concentrations was −0.1% (−6.7, 7.0) for estradiol, −0.3% (−7.0, 7.0) for FSH, 0.4% (−5.9, 7.1) for LH, and 1.2% (−5.1, 7.9) for Inhibin-B, and 0.7% (−5.4, 7.2) for prolactin and the adjusted mean difference was −2.2 ng/dL (−21.4, 17.0) for Testosterone and −1.4 nmol/L (−3.0, 0.2) for SHBG. The adjusted incidence rate (95% CI) of disomy associated with a 500 meter increase in residential distance to a major roadway was 0.93 (0.71, 1.22) for XX18, 0.96 (0.84, 1.10) for YY18, 1.08 (0.85, 1.37) for XY18 and 1.01 (0.86, 1.18) for the total disomy (Table 4). Consistent results were observed in the sensitivity analyses after restricting to one semen sample per man (Supplementary Table 5), after excluding men with a history of reproductive diseases (Supplementary Table 6), when we used different cutoffs to define the distance to major roadways categories, and when we further adjusted for other covariates (data not shown).

Discussion

In this cohort of men residing in Massachusetts and attending a fertility center, we did not observe any associations between residential proximity to major roadways, as a proxy for traffic–related air pollution, and various semen characteristics, sperm DNA integrity parameters, sperm aneuploidy measures, or serum reproductive hormone concentrations.

Although not thoroughly understood, animal and experimental data suggest the potential mechanisms that could explain our initial hypothesis could be increased systemic inflammation (Panasevich et al., 2009), oxidative stress (Gualtieri et al., 2012), endothelial dysfunction (Wauters et al., 2013), and damage to male’s gametes (Somers, 2011) with heightened exposure to air pollution due to traffic. All of these pathways have been shown to potentially affect spermatogenesis, reproductive hormones, and male reproductive function.

Previous epidemiological studies found that men working at motorway tollgates, who are expected to have high diesel exhaust exposure, had lower semen quality parameters (Guven et al., 2008) compared to office personnel and higher spermatozoa with damaged chromatin and DNA fragmentation compared to unexposed healthy men (Calogero et al., 2011). However, recently, consistent with our results, Nobles et al. (Nobles et al., 2018), reported that in 467 male partners enrolled in a time to pregnancy study from Michigan and Texas, low to moderate exposure criteria air pollutants and fine particle constituents in the 72 days before ejaculation was not associated with semen quality, except for sperm head parameters (which we did not measure in our study). They concluded that moderate levels of ambient air pollution may not be a major contributor to semen quality. Also, consistently with our results, Hansen et al.(Hansen et al., 2010) reported that in 228 fertile men in the United States (US), exposure to ozone or PM2.5 at low levels (below the current National Ambient Air Quality Standards) were not associated with semen quality outcomes. However, other studies in the US such as (Hammoud et al., 2010) reported that PM2.5 exposure was significantly associated with decreased sperm motility, but not sperm concentration.

Although some studies outside the US did not observe a detrimental effect (Radwan et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2014), other studies outside the US have found that one or more air pollution proxies was associated with one or more of the semen parameters. Santi et al.(Santi et al., 2016) in Italy reported a significantly lower morphologically normal sperm with higher PM10 exposure and lower sperm concentrations with higher PM2.5 exposure. In China, PM10 exposure was negatively associated with morphologically normal sperm but positively associated with sperm progressive motility, and PM10–2.5 exposure was inversely associated with sperm concentration(Zhou et al., 2018). In another Chinese study, relatively high PM2.5 and PM10 exposures were associated with decreased sperm concentration and count but not sperm motility (Wu et al., 2017).

It is worth noting here that it is difficult to compare our results with previous studies because proximity to major roadways, although correlated, does not necessarily represent exposure to specific pollutants. One study(Wijesekara et al., 2015), which included 300 infertile men in Sri Lanka, compared the semen quality of men who lived in areas less than 50m from a main road or who worked in an industry emanating toxicants to unexposed men and found significant impairments on a variety of semen quality parameters. However, the analysis did not separate between occupationally and environmentally exposed men and traffic proximity was not the main focus of the study, therefore it is also difficult to compare their results to ours.

Regarding the other markers of male reproductive health such as sperm DNA integrity, sperm disomy, and serum reproductive hormones, the previous literature is also mixed. Three (Calogero et al., 2011; Rubes et al., 2005; Selevan et al., 2000) out of six publications found that air pollution exposure was significantly associated with increased DNA fragmentation. These three studies were conducted in the Czech Republic and Italy which are difficult to compare to the US. However, the other three studies conducted in Italy, Poland and the US did not observe any association between air pollution exposure and DNA fragmentation (De Rosa et al., 2003; Hansen et al., 2010; Radwan et al., 2016). Jurewicz et al.(Jurewicz et al., 2015) observed positive associations between PM2.5 using EPA monitors (obtained from the AirBase database) and disomy Y in men attending a fertility clinic in Poland. Zhou et al.(Zhou et al., 2018) observed no associations between PM10 and PM2.5 as measured from two ambient air quality monitoring stations and reproductive hormones among 796 men in China; however Radwan et al.(Radwan et al., 2016) reported negative associations of PM10, PM2.5, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen dioxides with testosterone among 327 men in Poland. While our study observed no difference in these outcomes across categories of distance to major roadways, our limited sample sizes for these outcome may have decreased our ability to observe a significant effect, if any.

The inconsistency in the literature concerning the effects of air pollution on male fertility parameters could be explained due to differences in study populations (e.g. sperm donors vs. fertile men vs. infertile men); exposure metrics used to quantify air pollution (e.g. PM2.5 vs. PM10 vs. occupational proxies), measurement error in the exposure according to how the air pollution metric was quantified (e.g. based on address vs. zipcode, nearest monitor vs. spatiotemporal model), geographic location (e.g. relative concentrations and types of air pollutants), and control for confounders. Many of the previous studies also had small sample sizes, which could have limited their ability to detect a significant effect. In our study, we had 80% power at alpha level of 0.05 for detecting a change of 3% for the percent of motile sperm, 7.5 μm for CE, 3 μm for % tail and 3 ng/dL for total testosterone and a 4 to 10 difference in disomy numbers for a 500 meter increase in residential distance to major roadway. Given our large sample size, particularly for the traditional semen quality parameters, it is unlikely that low power could explain our null results. However, the low power could explain our null results for the DNA integrity, hormones, and disomy. It is also difficult to compare our results with non–US studies due to the different ranges and sources of air pollution exposures and due to different National Ambient Air Quality Standards across countries.

Our study had several limitations. While many studies suggest that metrics such as distance to roadways are reasonable surrogates for exposure to ambient levels of traffic-related air pollutants(Dorans et al., 2017; Gilbert et al., 2003; Hart et al., 2014; van Roosbroeck et al., 2006), it is not without error. We had no information about the time spent outdoors, location of their work and its proximity to traffic, different sources of air pollution, and variability due to lifestyle factors such as commuting route and time spent in traffic and home characteristics (e.g., orientation relative to winds and/or to the roadways, age of the home, ventilation). Furthermore, because residential distance to major roadways is correlated with many other environmental exposures such as noise, it is challenging to distinguish their independent effects. Although we have information on the season of sample collection, we do not have information about the seasonal or temporal trends in traffic-related exposures, which could be an important effect modifier. All of these factors could have contributed to non-differential exposure misclassification, which would have attenuated results towards the null. Thus, it is hard to determine whether our null results for residential proximity to roadways and semen quality and reproductive hormones are due to these combined sources of measurement error or truly due to lack of biological effect. Additionally, residential proximity to major roadways does not capture the dispersion and degradation profiles of the actual pollutant mix that originates from roadways. Future research in this cohort using estimates of specific traffic-related air pollutants is planned to verify these results. Generalizability could be limited because our study population was recruited from a fertility clinic and the men were predominantly Caucasian men of high socioeconomic status who resided in an urban area of Massachusetts. However, their semen quality parameters were comparable to those of fertile US adult men (Swan et al., 2003) and previous work from our group has suggested that there is no differential participation in our study based on semen quality (Hauser et al., 2005). In addition, men included in the analysis of sperm DNA damage, reproductive hormones, and sperm aneuploidy were similar to men who did not, minimizing the likelihood of selection bias. Finally, we cannot exclude the role of residual confounding in observational studies. In particular, given the high socioeconomic status of many men in our population, it is possible that their ambient exposures due to living close to a major roadway (e.g. neighborhood socioeconomic status, noise pollution, etc.) differed from those living near a major roadway where the median income is much lower. This could have biased the results either away or towards the null. However, our collection and adjustmentfor many covariates makesthis less likely.

Despite limitations, our study had several strengths. We had data for many reproductive outcomes including clinical semen parameters as well as measures of sperm DNA integrity, sperm aneuploidy, and serum reproductive hormones that can allow for more sensitive assessments of male reproductive health but are less commonly studied. For example, while rare, sex–chromosome disomy occurs twice as frequently as autosomal disomy and has significant impacts on the ability to father healthy offspring (Perry et al., 2016).

Conclusions

In this cohort of men based in a fertility center in Massachusetts, residential distance to major roadways was not associated with any of the semen quality, sperm DNA integrity, sperm aneuploidy or serum hormones parameters under study. More research is needed in this important area using more specific air pollution exposure metrics to provide a better understanding of the effects of air pollution on men’s reproductive health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support: NIH: K99 ES026648, R01 ES009718 & P30 ES000002

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all members of the EARTH study team, specifically research nurse Myra G. Keller, senior research staff Patricia Morey, and the physicians and staff at the Massachusetts General Hospital fertility center. A special thank you is due to all of the study participants.

Abbreviations

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

- GIS

Geographical Information System

- MassDOT

The Massachusetts Department of Transportation

- CE

Comet extent

- TDM

tail distributed moment

- FISH

Sperm fluorescence in–situ hybridization

- FSH

follicle–stimulating hormone

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- SHBG

sex hormone–binding globulin

- CV

coefficient of variation

- ORs

odds ratios

- PM

particulate matter

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baumgartner A, Van Hummelen P, Lowe XR, Adler ID, Wyrobek AJ. Numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities detected in human sperm with a combination of multicolor FISH assays. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 1999;33:49–58. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2280(1999)33:1<49::aid-em6>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calogero AE, La Vignera S, Condorelli RA, Perdichizzi A, Valenti D, Asero P, Carbone U, Boggia B, De Rosa N, Lombardi G, D’Agata R, Vicari LO, Vicari E, De Rosa M. Environmental car exhaust pollution damages human sperm chromatin and DNA. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2011;34:e139–143. doi: 10.1007/BF03346722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavarro JE, Toth TL, Wright DL, Meeker JD, Hauser R. Body mass index in relation to semen quality, sperm DNA integrity, and serum reproductive hormone levels among men attending an infertility clinic. Fertility and sterility. 2010:93. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa M, Zarrilli S, Paesano L, Carbone U, Boggia B, Petretta M, Maisto A, Cimmino F, Puca G, Colao A, Lombardi G. Traffic pollutants affect fertility in men. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2003;18:1055–1061. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M, Hu Y, Schwartz J, Koh WP, Yuan JM, Sesso HD, Ma J, Chavarro J, Hu FB, Pan A. Delineation of body mass index trajectory predicting lowest risk of mortality in U.S. men using generalized additive mixed model. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:698–703. e692. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorans KS, Wilker EH, Li W, Rice MB, Ljungman PL, Schwartz J, Coull BA, Kloog I, Koutrakis P, D’Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, O’Donnell CJ, Mittleman MA. Residential proximity to major roads, exposure to fine particulate matter and aortic calcium: the Framingham Heart Study, a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013455. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duty SM, Singh NP, Silva MJ, Barr DB, Brock JW, Ryan L, Herrick RF, Christiani DC, Hauser R. The relationship between environmental exposures to phthalates and DNA damage in human sperm using the neutral comet assay. Environmental health perspectives. 2003;111:1164–1169. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M, Naya M, Horimoto M, Kato H. Developmental toxicity of diesel exhaust: a review of studies in experimental animals. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, NY) 2013;42:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert NL, Woodhouse S, Stieb DM, Brook JR. Ambient nitrogen dioxide and distance from a major highway. Sci Total Environ. 2003;312:43–46. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri M, Longhin E, Mattioli M, Mantecca P, Tinaglia V, Mangano E, Proverbio MC, Bestetti G, Camatini M, Battaglia C. Gene expression profiling of A549 cells exposed to Milan PM2.5. Toxicology letters. 2012;209:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven A, Kayikci A, Cam K, Arbak P, Balbay O, Cam M. Alterations in semen parameters of toll collectors working at motorways: does diesel exposure induce detrimental effects on semen? Andrologia. 2008;40:346–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2008.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud A, Carrell DT, Gibson M, Sanderson M, Parker-Jones K, Peterson CM. Decreased sperm motility is associated with air pollution in Salt Lake City. Fertility and sterility. 2010;93:1875–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen C, Luben TJ, Sacks JD, Olshan A, Jeffay S, Strader L, Perreault SD. The effect of ambient air pollution on sperm quality. Environmental health perspectives. 2010;118:203–209. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart JE, Chiuve SE, Laden F, Albert CM. Roadway proximity and risk of sudden cardiac death in women. Circulation. 2014;130:1474–1482. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser R, Godfrey-Bailey L, Chen Z. Does the potential for selection bias in semen quality studies depend on study design? Experience from a study conducted within an infertility clinic. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2005;20:2579–2583. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedlinska-Krakowska M, Gizejewski Z, Dietrich GJ, Jakubowski K, Glogowski J, Penkowski A. The effect of increased ozone concentrations in the air on selected aspects of rat reproduction. Polish journal of veterinary sciences. 2006;9:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurewicz J, Radwan M, Sobala W, Polanska K, Radwan P, Jakubowski L, Ulanska A, Hanke W. The relationship between exposure to air pollution and sperm disomy. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 2015;56:50–59. doi: 10.1002/em.21883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karner AA, Eisinger DS, Niemeier DA. Near-roadway air quality: synthesizing the findings from real-world data. Environmental science & technology. 2010;44:5334–5344. doi: 10.1021/es100008x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger TF, Acosta AA, Simmons KF, Swanson RJ, Matta JF, Oehninger S. Predictive value of abnormal sperm morphology in in vitro fertilization. Fertility and sterility. 1988;49:112–117. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo-Irie M, Oshio S, Niwata Y, Ishihara A, Sugawara I, Takeda K. Pre- and postnatal exposure to low-dose diesel exhaust impairs murine spermatogenesis. Inhalation toxicology. 2011;23:805–813. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2011.610834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente R, Garcia-Blaquez N, Jacquemin B, Checa MA. Outdoor air pollution and sperm quality. Fertility and sterility. 2016;106:880–896. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao XQ, Zhang Z, Lau AK, Chan T-C, Chuang YC, Chan J, Lin C, Guo C, Jiang WK, Tam T, Hoek G, Kan H, Yeoh E-k, Chang L-y. Exposure to ambient fine particulate matter and semen quality in Taiwan. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Legare C, Droit A, Fournier F, Bourassa S, Force A, Cloutier F, Tremblay R, Sullivan R. Investigation of male infertility using quantitative comparative proteomics. Journal of proteome research. 2014;13:5403–5414. doi: 10.1021/pr501031x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine H, Jørgensen N, Martino-Andrade A, Mendiola J, Weksler-Derri D, Mindlis I, Pinotti R, Swan SH. Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Human reproduction update. 2017:1–14. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis JF, Thoma ME, Sørensen DN, McLain AC, King RB, Sundaram R, Keiding N, Buck Louis GM. The prevalence of couple infertility in the United States from a male perspective: evidence from a nationally representative sample. Andrology. 2013;1:741–748. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2013.00110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe ME, Williams PL, Korrick SA, Altshul LM, Perry MJ. Environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and p,p′-DDE and sperm sex-chromosome disomy. Environmental health perspectives. 2012;120:535–540. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassan FL, Coull BA, Skakkebaek NE, Williams MA, Dadd R, Minguez-Alarcon L, Krawetz SA, Hait EJ, Korzenik JR, Moss AC, Ford JB, Hauser R. A crossover-crossback prospective study of dibutyl-phthalate exposure from mesalamine medications and semen quality in men with inflammatory bowel disease. Environment international. 2016;95:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobles CJ, Schisterman EF, Ha S, Kim K, Mumford SL, Buck Louis GM, Chen Z, Liu D, Sherman S, Mendola P. Ambient air pollution and semen quality. Environmental research. 2018;163:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panasevich S, Leander K, Rosenlund M, Ljungman P, Bellander T, de Faire U, Pershagen G, Nyberg F. Associations of long- and short-term air pollution exposure with markers of inflammation and coagulation in a population sample. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66:747–753. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.043471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry MJ, Chen X, McAuliffe ME, Maity A, Deloid GM. Semi-automated scoring of triple-probe FISH in human sperm: methods and further validation. Cytometry Part A: the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2011;79:661–666. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry MJ, Young HA, Grandjean P, Halling J, Petersen MS, Martenies SE, Karimi P, Weihe P. Sperm Aneuploidy in Faroese Men with Lifetime Exposure to Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p,p′-DDE) and Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) Pollutants. Environmental health perspectives. 2016;124:951–956. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan M, Jurewicz J, Polanska K, Sobala W, Radwan P, Bochenek M, Hanke W. Exposure to ambient air pollution--does it affect semen quality and the level of reproductive hormones? Annals of human biology. 2016;43:50–56. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2015.1013986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubes J, Selevan SG, Evenson DP, Zudova D, Vozdova M, Zudova Z, Robbins WA, Perreault SD. Episodic air pollution is associated with increased DNA fragmentation in human sperm without other changes in semen quality. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2005:20. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi D, Vezzani S, Granata AR, Roli L, De Santis MC, Ongaro C, Donati F, Baraldi E, Trenti T, Setti M, Simoni M. Sperm quality and environment: A retrospective, cohort study in a Northern province of Italy. Environmental research. 2016;150:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selevan SG, Borkovec L, Slott VL, Zudova Z, Rubes J, Evenson DP, Perreault SD. Semen quality and reproductive health of young czech men exposed to seasonal air pollution. Environmental health perspectives. 2000:108. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol RZ, Kraft P, Fowler IM, Mamet R, Kim E, Berhane KT. Exposure to Environmental Ozone Alters Semen Quality. Environmental health perspectives. 2006;114:360–365. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers CM. Ambient air pollution exposure and damage to male gametes: human studies and in situ ‘sentinel’ animal experiments. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2011;57:63–71. doi: 10.3109/19396368.2010.500440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SH, Brazil C, Drobnis EZ, Liu F, Kruse RL, Hatch M, Redmon JB, Wang C, Overstreet JW. Geographic differences in semen quality of fertile U.S. males. Environmental health perspectives. 2003;111:414–420. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Tsukue N, Yoshida S. Endocrine-disrupting activity of chemicals in diesel exhaust and diesel exhaust particles. Environmental sciences: an international journal of environmental physiology and toxicology. 2004;11:33–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma ME, McLain AC, Louis JF, King RB, Trumble AC, Sundaram R, Buck Louis GM. Prevalence of infertility in the United States as estimated by the current duration approach and a traditional constructed approach. Fertility and Sterility. 2013;99:1324–1331. e1321. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukue N, Toda N, Tsubone H, Sagai M, Jin WZ, Watanabe G, Taya K, Birumachi J, Suzuki AK. Diesel exhaust (DE) affects the regulation of testicular function in male Fischer 344 rats. Journal of toxicology and environmental health Part A. 2001;63:115–126. doi: 10.1080/15287390151126441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Roosbroeck S, Wichmann J, Janssen NA, Hoek G, van Wijnen JH, Lebret E, Brunekreef B. Long-term personal exposure to traffic-related air pollution among school children, a validation study. Sci Total Environ. 2006;368:565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wauters A, Dreyfuss C, Pochet S, Hendrick P, Berkenboom G, van de Borne P, Argacha JF. Acute exposure to diesel exhaust impairs nitric oxide-mediated endothelial vasomotor function by increasing endothelial oxidative stress. Hypertension. 2013;62:352–358. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HY, Hsueh YH, Messam LL, Hertz-Picciotto I. Methods of covariate selection: directed acyclic graphs and the change-in-estimate procedure. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1182–1190. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO laboratory manual for the Examination and processing of human semen. 5. World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesekara GU, Fernando DM, Wijerathna S, Bandara N. Environmental and occupational exposures as a cause of male infertility. The Ceylon medical journal. 2015;60:52–56. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v60i2.7090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Jin L, Shi T, Zhang B, Zhou Y, Zhou T, Bao W, Xiang H, Zuo Y, Li G, Wang C, Duan Y, Peng Z, Huang X, Zhang H, Xu T, Li Y, Pan X, Xia Y, Gong X, Chen W, Liu Y. Association between ambient particulate matter exposure and semen quality in Wuhan, China. Environment international. 2017;98:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Cui Z, Yang S, Han X, Chen G, Zhou Z, Zhai C, Ma M, Li L, Cai M, Li Y, Ao L, Shu W, Liu J, Cao J. Air pollution and decreased semen quality: a comparative study of Chongqing urban and rural areas. Environmental pollution (Barking, Essex: 1987) 2014;187:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Jiang C, Chen Q, Yang H, Wang X, Zou P, Sun L, Liu J, Li L, Li L, Huang L, Chen H, Ao L, Zhou Z, Liu J, Cui Z, Cao J. Exposures to Atmospheric PM10 and PM10–2.5 Affect Male Semen Quality: Results of MARHCS Study. Environmental science & technology. 2018 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.