Abstract

Background

Recent evidence suggests that horizontal transfer plays a significant role in the evolution of of transposable elements (TEs) in eukaryotes. Many cases of horizontal TE transfer (HTT) been reported in animals and plants, however surprisingly few examples of HTT have been reported in fungi.

Findings

Here I report evidence for a novel HTT event in fungi involving Tsu4 in Saccharomyces paradoxus based on (i) unexpectedly high similarity between Tsu4 elements in S. paradoxus and S. uvarum, (ii) a patchy distribution of Tsu4 in S. paradoxus and general absence from its sister species S. cerevisiae, and (iii) discordance between the phylogenetic history of Tsu4 sequences and species in the Saccharomyces sensu stricto group. Available data suggests the HTT event likely occurred somewhere in the Nearctic, Neotropic or Indo-Australian part of the S. paradoxus species range, and that a lineage related to S. uvarum or S. eubayanus was the likely donor species. The HTT event has led to massive proliferation of Tsu4 in the South American lineage of S. paradoxus, which exhibits partial reproductive isolation with other strains of this species because of multiple reciprocal translocations. Full-length Tsu4 elements are associated with both breakpoints of one of these reciprocal translocations.

Conclusions

This work shows that comprehensive analysis of TE sequences in essentially-complete genome assemblies derived from long-read sequencing provides new opportunities to detect HTT events in fungi and other organisms. This work also provides support for the hypothesis that HTT and subsequent TE proliferation can induce genome rearrangements that contribute to post-zygotic isolation in yeast.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13100-018-0122-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Transposable element, Horizontal transfer, Yeast, Genome rearrangement

Main Text

Horizontal transfer is increasingly thought to play an important role in shaping the diversity of transposable elements (TEs) in eukaryotic genomes [1–3]. Since the initial discovery of horizontal transfer of the P element from Drosophila willistoni to D. melanogaster [4], a large number of cases of horizontal TE transfer (HTT) have been reported, especially among animals species (data compiled in [5]). However, surprisingly few cases of HTT have been reported in fungi [6–12], despite an abundance of genomic resources in this taxonomic group. Advances in long-read whole genome shotgun sequencing now allow comprehensive analysis of TE sequences in high-quality genome assemblies, and may therefore provide new opportunities for detecting HTT events in fungi and other organisms.

For example, a recent study by Yue et al. [13] reported essentially-complete PacBio genome assemblies for seven strains of S. cerevisiae and five strains of S. paradoxus. Analysis of TEs in these assemblies revealed a surprisingly high copy number for the Ty4 family in one strain of S. paradoxus from South America (UFRJ50816; n =23 copies) [13]. This was a noteworthy observation for two reasons: (i) Ty4 is typically found at low copy number in yeast strains [14–16], and (ii) S. American strains of S. paradoxus exhibit partial reproductive isolation with other strains of this species, which principally results from multiple reciprocal translocations thought to have arisen by unequal crossing-over between dispersed repetitive elements such as Ty elements [17].

I independently replicated the curious observation of exceptionally high Ty4 copy number in S. paradoxus UFRJ50816 using a RepeatMasker-based annotation pipeline similar to that described in [11], which identifies and classifies Ty elements as full-length, truncated, or solo long terminal repeats (LTRs). Using the results of this initial annotation, I generated a multiple alignment of all full-length Ty4 elements identified in these 12 assemblies. Preliminary phylogenetic analysis revealed that the full-length Ty4 elements from S. paradoxus UFRJ50816 formed a monophyletic clade of very similar sequences that were highly divergent from other full-length Ty4 elements identified in S. cerevisiae (S288c, Y12, YPS128) or S. paradoxus (N44). Surprisingly, BLAST analysis at NCBI using representative members of this divergent Ty4-like clade revealed that they were more similar to the Tsu4 element from the related yeast species S. uvarum (Genbank: AJ439550) [18] than they were to the original S. cerevisiaeTy4 query sequence (Genbank: S50671). This result suggested that the unusually high copy number of Ty4 in S. paradoxus UFRJ50816 reported by Yue et al. [13] could actually be the consequence of rapid expansion of Tsu4 following a HTT event from a S. uvarum-like donor.

To better characterize Ty4 and Tsu4 content in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus, I first identified a canonical S. paradoxusTsu4 element. To do this, I included the S. uvarumTsu4 query sequence in the TE library from [11] and re-annotated Ty elements in S. paradoxus UFRJ50816 using the same RepeatMasker-based strategy as above. I also performed de novo identification of full-length LTR elements in S. paradoxus UFRJ50816 using LTRharvest [19], then overlapped results from RepeatMasker and LTRharvest to identify full-length Tsu4 elements, generated a consensus sequence from these elements, and finally identified the genomic copy (chrII:554570-560566) that clustered most closely with the consensus sequence of full-length Tsu4 elements in a neighbor-joining tree. The canonical S. paradoxusTsu4 element is 5,997 bp in length, with 293 bp LTRs and two overlapping reading frames predicted to encode GAG (358 amino acids) and POL (1419 amino acids). Codon-based alignment with PRANK [20] and estimation of dN/dS ratios under PAML model M0 using ETE [21, 22] revealed that selective constraints have operated on both GAG (0.34) and POL (0.21) sequence divergence between S. uvarum and S. paradoxusTsu4 canonical elements. Estimates of dS for GAG (0.23) and POL (0.24) between S. uvarum and S. paradoxusTsu4 canonical elements were over four times lower than the median dS (1.01) for nuclear coding sequences estimated under M0 for these species using 4554 high-confidence alignments from [23]. This observation supports HTT of Tsu4 and argues against various modes of vertical inheritance to explain the similarity between S. paradoxus and S. uvarumTsu4.

I then performed a final annotation of Ty elements in all 12 assemblies from Yue et al. [13] using the TE library from [11] plus the newly-identified S. paradoxusTsu4 canonical element. Full-length, truncated and solo LTR counts for Tsu4 and Ty4 can be found in Table 1. Similar data for all Ty families in these genomes can be found in Additional file 1 and coordinates of all annotated Ty elements in these genomes can be found in Additional file 2. This improved annotation revealed a low copy number of full-length Ty4 elements for S. cerevisiae S288c, Y12, and YPS128 as well as S. paradoxus N44, which is typical of this family [14–16]. Solo LTRs for Ty4 were found in all strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus with PacBio data from from Yue et al. [13]. Solo LTRs arise by intra-element LTR-LTR recombination and serve as useful markers of past transpositional activity [24]. These results suggest that Ty4 was present in the common ancestor of both S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus and that this family has been maintained at low copy number or become inactive in different lineages of each species.

Table 1.

Ty4 and Tsu4 content in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus PacBio assemblies from Yue et al. [13]

| Species | Strain | # Ty4 full | # Ty4 truncated | # Ty4 solo LTR | # Tsu4 full | # Tsu4 truncated | # Tsu4 solo LTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scer | S288c | 3 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scer | DBVPG6044 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scer | DBVPG6765 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scer | SK1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scer | Y12 | 4 | 1 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scer | YPS128 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scer | UWOPS03-461.4 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spar | CBS432 | 0 | 2 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spar | N44 | 3 | 3 | 106 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spar | YPS138 | 0 | 0 | 49 | 1 | 0 | 18 |

| Spar | UFRJ50816 | 0 | 1 | 45 | 22 | 2 | 105 |

| Spar | UWOPS91-917.1 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 1 | 1 | 88 |

Numbers of full-length elements (both LTRs present and internal region present with > 95% coverage of canonical internal region), truncated elements (internal region present with < 95% coverage of canonical internal region), or solo LTRs (no match to internal region) were estimated using a RepeatMasker (version 4.0.5) based strategy and a custom library of Ty elements from [11] supplemented with S. paradoxusTsu4

In contrast, I found evidence for full-length Tsu4 sequences in only three strains of S. paradoxus from S. America (UFRJ50816, n=22), N. America (YPS138, n=1) and Hawaii (UWOPS91-917.1, n=1) (Table 1). S. American, N. American, and Hawaiian lineages of S. paradoxus form a monophyletic group that is distinct from a clade containing European and Far-Eastern lineages from the Old World [13, 25]. S. paradoxus strains with full-length copies of Tsu4 were devoid of full-length Ty4 elements, and vice versa. Crucially, only these three S. paradoxus strains had solo LTRs for Tsu4, suggesting they are the only lineages in which Tsu4 has been active in the past. Consistent with a more recent presence in the S. paradoxus genome, solo LTRs for Tsu4 exhibited ≥3-fold lower average pairwise divergence than Ty4 solo LTRs relative to their respective canonical elements within the genomes of UFRJ50816 (Tsu4: 0.02, Ty4: 0.10), YPS138 (Tsu4: 0.03, Ty4: 0.10) and UWOPS91-917.1 (Tsu4: 0.04, Ty4: 0.12).

The 22 full-length copies of Tsu4 identified in UFRJ50816 are distributed on 11 different chromosomes, indicating proliferation in UFRJ50816 is not simply due to tandem duplication. Twelve of the full-length Tsu4 copies in UFRJ50816 are flanked by 5 bp target site duplications (TSDs) that can be automatically identified by LTRharvest [19] and 21 are within ± 1 kb of a tRNA gene, similar to what has been reported previously for Ty4 in S. cerevisiae [15, 26]. Diagnostic hallmarks of active Ty element transposition such as 5 bp TSDs and tRNA targeting suggest that Tsu4 has been recently active in UFRJ50816 and also argue against the possibility that Tsu4 sequences in S. paradoxus are due to contamination in DNA samples.

I next confirmed the general absence of Tsu4 in S. cerevisiae by BLAST analysis of an additional 336 S. cerevisiae whole genome shotgun (WGS) assemblies at NCBI (taxid: 4932), which revealed only one nearly complete sequence with high similarity to Tsu4 from a S. cerevisiae strain isolated from a rum distillery in the West Indies (> 80% coverage and > 80% identity, see below) [27]. The patchy distribution of Tsu4 sequences in S. paradoxus and general absence from S. cerevisiae suggests that this element was not present in the common ancestor of these species, and instead was recently acquired by a S. paradoxus lineage somewhere in the Nearctic, Neotropic or Indo-Australian region, possibly in a strain lacking an active Ty4. In principle, the patchy distribution of Tsu4 in S. paradoxus and absence from S. cerevisiae could be explained by vertical inheritance from the common ancestor of S. uvarum, S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus followed by multiple losses in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus, however the much lower dS between S. uvarum and S. paradoxusTsu4 coding regions relative to host genes argues against this scenario.

To provide further support for the hypothesis that Tsu4 recently invaded S. paradoxus by HTT, I constructed a maximum likelihood phylogeny of all full-length Ty4 and Tsu4 sequences identified in the 12 strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus from Yue et al. [13] using RAxML [28]. In this analysis, I also included all complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 elements identified by BLAST in 392 Saccharomyces WGS assemblies at NCBI (taxid: 4930) that had high similarity to the S. uvarumTsu4 query sequence (> 80% coverage and > 80% identity). These additional 12 Tsu4 sequences include three sequences from the same strain of S. uvarum in which Tsu4 was discovered, one sequence from S. mikatae, one sequence from S. kudriavzevii, one sequence each from four strains of S. pastorianus, two sequences from an unknown Saccharomyces species (strain M14) isolated in China that is involved in lager brewing, and the single sequence from S. cerevisiae (strain 245) mentioned above (Additional file 3) [27, 29–31]. S. mikatae is the most closely related outgroup species to the S. cerevisiae/S. paradoxus clade, followed by S. kudriavzevii, then a clade containing S. uvarum and S. eubayanus (reviewed in [32]). S. pastorianus is a hybrid species used in lager brewing containing subgenomes from S. cerevisiae and S. eubayanus [30, 33, 34]. The multiple sequence alignment and maximum likelihood tree for this dataset can be found in Additional files 4 and 5, respectively.

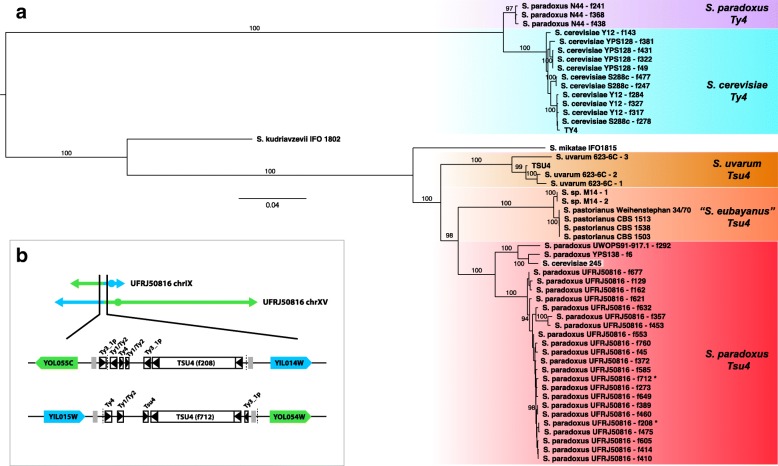

Figure 1a clearly shows that Tsu4-like sequences form a well-supported monophyletic clade that is distinct from the Ty4 lineage present in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus. All S. paradoxusTsu4 sequences form a single clade that also contains the Tsu4 sequence from S. cerevisiae strain 245, suggesting one initial HTT event into S. paradoxus followed by a secondary HTT event from S. paradoxus into S. cerevisiae. The most closely-related lineage to the S. paradoxusTsu4 clade is a clade containing sequences from S. pastorianus and Saccharomyces sp. M14, followed by a clade containing sequences from S. uvarum. The grouping of Tsu4 sequences from the hybrid species S. pastorianus with those from S. paradoxus and S. uvarum can most parsimoniously be explained if Tsu4 sequences from S. pastorianus are derived from the S. eubayanus component of the hybrid genome (see below). If this is true, then Tsu4 in S. paradoxus could plausibly have arisen via HTT from S. eubayanus, the sister species to S. uvarum. Tsu4 sequences from both S. mikatae and S. kudriavzevii are outgroups to the crown Tsu4 lineage, but group more closely to the Tsu4 lineage than to the Ty4 lineage with strong support. The observation that S. mikatae groups more closely Tsu4 with the crown Tsu4 lineage than S. kudriavzevii is incompatible with the accepted species tree [32], suggesting unequal rates of evolution or another potential HTT event involving Tsu4 between S. mikatae and the ancestor of S. uvarum and S. eubayanus. Despite unresolved issues with some aspects of the current Tsu4 phylogeny, the fact that S. uvarum is the closest pure species clustering with the S. paradoxus clade is clearly incompatible with the accepted tree for these species [32] and this discordance provides support for the conclusion that Tsu4 arose in S. paradoxus by HTT from S. uvarum or a closely related species like S. eubayanus.

Fig. 1.

Evolution of the Ty4/Tsu4 super-family in the Saccharomyces sensu stricto species group. a. Maximum likelihood phylogeny of all full-length Ty4 and Tsu4 elements from 12 strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus with PacBio assemblies from Yue et al. [13] plus all complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 elements identified in Saccharomyces WGS assemblies at NCBI. Labels are shown for branches in the maximum likelihood tree that are supported by ≥ 90% of bootstrap replicates. The scale bar for branch lengths is in substitutions per site, and the tree is midpoint rooted. Tsu4 sequences from hybrid strains (S. pastorianus and Saccharomyces sp. M14) were assigned to the S. eubayanus subgenome and presumed to have originated in S. eubayanus. b. Genome organization of the reciprocal translocation between chrIX and chrXV in UFRJ50816. Sequences from the standard arrangement chrIX are shown in blue, and sequences from the standard arrangement chrXV are shown in green. Protein-coding genes, tRNA genes, and solo LTRs are shown approximately to scale as solid arrows, grey rectangles and boxed arrowheads, respectively. Approximate translocation breakpoints in UFRJ50816 based on whole genome alignments can be localized to chrIX:252268-259232 and chrXV:320536-328356 (dashed lines). Full-length Tsu4 elements are present in both translocation breakpoints. The Tsu4 elements associated in the chrIX and chrXV reciprocal translocation between are denoted by asterices in panel a

To address the origin of Tsu4 sequences in S. pastorianus genomes and better understand potential donors for the HTT event, I aligned S. pastorianus WGS assemblies to a pan-genome comprised of S. cerevisiae S288c [13] and S. eubayanus FM1318 [34], a monosporic derivative of the S. eubayanus type strain which was isolated from Northwestern Patagonia, Argentina [33]. The Tsu4 sequences from all four strains of S. pastorianus are contained on scaffolds that align best to scaffolds from the S. eubayanus subgenome (Additional file 6), consistent with the general lack of Tsu4 in S. cerevisiae and the phylogenetic clustering of S. pastorianusTsu4 sequences with those from S. uvarum. In fact, Tsu4 sequences for all four S. pastorianus strains align to the same location in S. eubayanus (scaffold NC_030972.1), which together with their tight clustering on the tree suggests they are alleles of the same insertion event. Likewise, alignment of the Saccharomyces sp. M14 genome to a pan-genome of S. eubayanus and S. cerevisiae revealed large scaffolds that aligned to either scaffolds from S. eubayanus or chromosomes from S. cerevisiae (Additional file 7), in a similar pattern to the bona fideS. pastorianus group 2/Frohberg strain W34/70 (Additional file 8). Thus, Saccharomyces sp. M14 appears to be a hybrid of S. cerevisiae and S. eubayanus and may possibly be a previously-unidentified strain of S. pastorianus. The two Tsu4 sequences from Saccharomyces sp. M14 align to a different S. eubayanus scaffold (NC_030977.1) and form a cluster on the tree that is distinct from the S. pastorianusTsu4 sequences, suggesting they arose from different transposition events. None of the S. pastorianus/Saccharomyces sp. M14Tsu4 insertions are found in the S. eubayanus reference genome, nor are any other complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 sequences. Several distinct clades have been identified in S. eubayanus using whole genome sequence data: the reference strain (FM1318) is found in the Patagonia B-1 clade, while North American, Tibetan and the S. eubayanus subgenomes of S. pastorianus strains are found in the related but distinct Holoarctic clade [35]. Overall, the S. eubayanus subgenome localization and close affinity of S. pastorianus/Saccharomyces sp. M14Tsu4 sequences with S. paradoxusTsu4 sequences suggest that S. eubayanus is a viable donor for the Tsu4 element that invaded S. paradoxus, and that Tsu4 has been recently active in the Holoarctic clade of S. eubayanus.

Within S. paradoxus, the deepest well-supported branches in the S. paradoxusTsu4 clade are between N. American/Hawaiian and S. American S. paradoxus lineages, suggesting the HTT event predates separation of these lineages and could therefore have occurred anywhere in the ancestral range for S. paradoxus in the Nearctic, Neotropic or Indo-Australian regions. All of the Tsu4 sequences in UFRJ50816 form a single clade, but bootstrap support for most branches within this clade are low, consistent with a recent proliferation event occurring after separation of S. American S. paradoxus from N. American and Hawaiian lineages. The single S. cerevisiaeTsu4 sequence found in a strain 245 (isolated from the French West Indies) clusters strongly with the Tsu4 sequence from the N. American S. paradoxus strain YPS138. Introgression of S. paradoxus DNA into S. cerevisiae has been observed previously [36–41], and thus introgression from a N. American-like lineage of S. paradoxusTsu4 into S. cerevisiae in the Caribbean could explain this secondary HTT event. As in N. American and Hawaiian lineages of S. paradoxus, Tsu4 in this S. cerevisiae lineage has not led to widespread proliferation, suggesting the high copy number of Tsu4 in UFRJ50816 is exceptional.

S. paradoxus UFRJ50816 was originally thought to represent a distinct species called S. cariocanus based on partial reproductive isolation with S. paradoxus tester strains [36, 42, 43]. Five reciprocal translocations have been identified on the lineage leading to UFRJ50816 relative to the standard S. paradoxus karyotype that account for most of this reproductive isolation [13, 17, 44]. To test whether the recent proliferation of of Tsu4 in UFRJ50816 has induced genome rearrangements involved in reproductive isolation, I identified translocation breakpoints in S. paradoxus UFRJ50816 relative to the standard karyotype S. paradoxus strain CBS432 using Mummer [45] and Ribbon [46]. Only one out of five translocations showed clear evidence for Tsu4 sequences at both breakpoints. Intriguingly, both breakpoints of the translocation between chrIX and chrXV (which has recently been shown to reduce spore viability by approximately 50% [44]) each contained a full-length Tsu4 element (Fig. 1b). These two elements are from the major clade of Tsu4 sequences found only in UFRJ50816, and are oriented in the directions expected if they were involved in a reciprocal exchange event. These results indicate that recent ectopic exchange among Tsu4 sequences is not the primary cause of the majority of translocations in UFRJ50816, however Tsu4 proliferation may have facilitated some genome rearrangements in the UFRJ50816 lineage.

In conclusion, here I report evidence for a novel HTT event in fungi involving Tsu4 in S. paradoxus based on (i) unexpectedly high similarity between Tsu4 elements in S. paradoxus and S. uvarum, (ii) a patchy distribution of Tsu4 in S. paradoxus and general absence from its sister species S. cerevisiae, and (iii) discordance between the phylogenetic history of Tsu4 sequences and host species trees. Based on available data, the most parsimonious scenario for the evolution of the Ty4/Tsu4 super-family is that an ancestral Ty4/Tsu4-like element was present in the ancestor of the Saccharomyces sensu stricto group, which diversified into Ty4 along the lineage leading to S. cerevisiae/S. paradoxus and into Tsu4 on the lineage leading to S. uvarum/S. eubayanus. Subsequently, a HTT event occurred introducing Tsu4 into the ancestor of non-Old World S. paradoxus, most likely from S. uvarum, S. eubayanus or a related species. This scenario is plausible since both S. uvarum and S. eubayanus have been sampled from sites in N. America and S. America that overlap or are in close proximity to the predicted range of S. paradoxus [33, 35, 47–49], and S. uvarum has been isolated from the same field sites as S. paradoxus in N. America [50]. Other more complex scenarios are also possible but would involve additional HTT events, such as HTT from S. uvarum/S. eubayanus to S. paradoxusvia intermediate species or multiple HTT events from an unidentified species into the ancestor of non-Old World S. paradoxus and S. uvarum, S. eubayanus or their common ancestor. A number of open questions remain about the Tsu4 HTT event, including which lineage donated Tsu4 to S. paradoxus, where the HTT event occurred, how widely Tsu4 has spread in S. paradoxus, and whether the HTT event was mediated by interspecific hybridization or some other mechanism. I also show that full-length Tsu4 elements are associated with the breakpoints of a reciprocal translocation that provides partial reproductive isolation between lineages of S. paradoxus from S. America and the rest of the world. These findings together with related work on Ty2 in S. cerevisiae [8, 11, 51] provide support for the hypothesis that HTT and subsequent proliferation can induce genome rearrangements that contribute to post-zygotic isolation in yeast.

Additional files

Ty content in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus PacBio assemblies. Numbers of full-length elements (both LTRs and internal region present with > 95% coverage of canonical internal region), truncated elements (internal region present with < 95% coverage of canonical internal region), or solo LTRs (no match to internal region) were identified using a RepeatMasker (version 4.0.5) based strategy and a custom library of Ty elements from [11] supplemented with S. paradoxusTsu4. (TSV 1.20 kb)

Coordinates of Ty elements in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus PacBio assemblies. Zip file of BED-formatted genome annotations for 12 strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus with PacBio assemblies. Full-length elements (f), truncated elements (t), or solo LTRs (s) were identified using a RepeatMasker (version 4.0.5) based strategy and a custom library of Ty elements from [11] supplemented with S. paradoxusTsu4. (ZIP 91.1 kb)

Summary of complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 sequences identified in Saccharomyces whole genome assemblies at NCBI. Accession number and coordinates of 12 complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 elements identified by BLAST in 392 Saccharomyces (taxid: 4930) WGS assemblies at NCBI that had high similarity (> 80% coverage and > 80% identity) to the Tsu4 query sequence (Genbank: AJ439550). (CSV 1.77 kb)

Multiple sequence alignment of Ty4 and Tsu4 elements in Saccharomyces sensu stricto species. Multiple sequence alignment of all full-length Ty4/Tsu4 elements from 12 strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus with PacBio assemblies from Yue et al. [13] plus all complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 elements identified in Saccharomyces WGS assemblies at NCBI (> 80% coverage and > 80% identity relative to the Tsu4 query sequence from S. uvarum). Fasta files of Ty4/Tsu4 sequences from all strains plus the Ty4 and Tsu4 query sequences were concatenated together and aligned using MAFFT (version 7.273-e; options: –thread 28) [52]. (TXT 335 kb)

Maximum likelihood tree file for Ty4 and Tsu4 elements in Saccharomyces sensu stricto species. Newick-formatted file of the maximum-likelihood tree of all full-length Ty4/Tsu4 elements from 16 strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus plus all complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 elements identified in Saccharomyces WGS assemblies at NCBI. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis was performed on the multiple alignment in Additional file 4 using RAxML (version: 8.2.4; options -T 28 -f a -x 12345 -p 12345 -N 100 -m GTRGAMMA) [28] excluding positions 1-166 and 6086-6476. (TXT 3.79 kb)

Coordinates of best-matches to scaffolds from S. pastorianus and Saccharomyces sp. M14 containing Tsu4 sequences vs. a pan-genome of S. eubayanus and S. cerevisiae genomes. S. pastorianus and Saccharomyces sp. M14 scaffolds were aligned to a pan-genome composed of scaffolds from S. eubayanus FM1318 (Genbank: GCF_001298625.1) and chromosomes from S. cerevisiae S288c (from [13]). Alignments were generated using nucmer (default parameters), delta-filter (options: -1 -l 2000), and show-coords (options: -lTH) in mummer 3.23 [45]. (TSV 5.15 kb)

Dot-plot of the Chinese lager strain Saccharomyces sp. M14vs. a pan-genome of S. eubayanus and S. cerevisiae genomes. Dot-plot of Saccharomyces sp. M14 scaffolds aligned to a pan-genome composed of scaffolds from S. eubayanus FM1318 (Genbank: GCF_001298625.1) and chromosomes from S. cerevisiae S288c (from [13]), showing that Saccharomyces sp. M14 contains subgenomes from both species and that this strain may be a previously-unidentified strain of the lager brewing species S. pastorianus. The dot-plot was generated using nucmer (default parameters) and mummerplot (options: --size large -fat --color -f --png) in mummer 3.23 [45]. (PDF 58.8 kb)

Dot-plot of the S. pastorianus group 2/Frohberg strain W34/70 vs. a pan-genome of S. eubayanus and S. cerevisiae genomes. Dot-plot of S. pastorianus group 2/Frohberg strain W34/70 scaffolds aligned to a pan-genome composed of scaffolds from S. eubayanus (Genbank: GCF_001298625.1) and chromosomes from S. cerevisiae (S288c from [13]), showing that S. pastorianus group 2/Frohberg strain W34/70 contains subgenomes from both species in a similar pattern as for Saccharomyces sp. M14 (see Additional file 7). The dot-plot was generated using nucmer (default parameters) and mummerplot (options: --size large -fat --color -f --png) in mummer 3.23 [45]. (PDF 69.8 kb)

Acknowledgements

CMB thanks Shan-ho Tsai and Yecheng Huang for bioinformatics application support; the Georgia Advanced Computing Resource Center for computing time; and Guilherme Dias, Douda Bensasson, and two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript.

Funding

CMB was supported by the University of Georgia Research Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

Canonical LTR and annotated internal sequences for S. paradoxusTsu4 have been submitted to Repbase. All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- HTT

Horizontal TE transfer

- LTR

Long terminal repeat

- TE

Transposable element

- TSD

Target site duplication

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13100-018-0122-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Author’s contributions

CMB conceived of the project, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Schaack S, Gilbert C, Feschotte C. Promiscuous DNA: horizontal transfer of transposable elements and why it matters for eukaryotic evolution. Trends Ecol Evol (Amst) 2010;25(9):537–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallau GL, Ortiz MF, Loreto ELS. Horizontal transposon transfer in eukarya: detection, bias, and perspectives. Genome Biol Evol. 2012;4(8):801–11. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallau GL, Vieira C, Loreto ELS. Genetic exchange in eukaryotes through horizontal transfer: connected by the mobilome. Mob DNA. 2018;9:6. doi: 10.1186/s13100-018-0112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniels SB, Peterson KR, Strausbaugh LD, Kidwell MG, Chovnick A. Evidence for horizontal transmission of the P transposable element between Drosophila species. Genetics. 1990;124(2):339–55. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dotto BR, Carvalho EL, Silva AF, Silva D, Fernando L, Pinto PM, Ortiz MF, Wallau GL. HTT-DB: Horizontally transferred transposable elements database. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(17):2915–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobinson KF, Harris RE, Hamer JE. Grasshopper, a long terminal repeat (LTR) retroelement in the phytopathogenic fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1993;6(1):114–26. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-6-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daboussi M-J, Davière J-M, Graziani S, Langin T. Evolution of the Fot1 transposons in the genus Fusarium: discontinuous distribution and epigenetic inactivation. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19(4):510–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liti G, Peruffo A, James SA, Roberts IN, Louis EJ. Inferences of evolutionary relationships from a population survey of LTR-retrotransposons and telomeric-associated sequences in the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex. Yeast. 2005;22(3):177–92. doi: 10.1002/yea.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novikova O, Fet V, Blinov A. Non-LTR retrotransposons in fungi. Funct Integr Genomics. 2009;9(1):27–42. doi: 10.1007/s10142-008-0093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amyotte SG, Tan X, Pennerman K, del Mar Jimenez-Gasco M, Klosterman SJ, Ma L-J, Dobinson KF, Veronese P. Transposable elements in phytopathogenic Verticillium spp.: insights into genome evolution and inter- and intra-specific diversification. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:314. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr M, Bensasson D, Bergman CM. Evolutionary genomics of transposable elements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):50978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarilar V, Bleykasten-Grosshans C, Neuveglise C. Evolutionary dynamics of hAT DNA transposon families in Saccharomycetaceae. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7(1):172–90. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yue J-X, Li J, Aigrain L, Hallin J, Persson K, Oliver K, Bergstrom A, Coupland P, Warringer J, Lagomarsino MC, Fischer G, Durbin R, Liti G. Contrasting evolutionary genome dynamics between domesticated and wild yeasts. Nat Genet. 2017;49(6):913–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.3847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stucka R, Lochmäller H, Feldmann H. Ty4, a novel low-copy number element in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: one copy is located in a cluster of Ty elements and tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17(13):4993–5002. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.13.4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JM, Vanguri S, Boeke J, Gabriel A, Voytas DF. Transposable elements and genome organization: a comprehensive survey of retrotransposons revealed by the complete Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome sequence. Genome Res. 1998;8(5):464–78. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleykasten-Grosshans C, Friedrich A, Schacherer J. Genome-wide analysis of intraspecific transposon diversity in yeast. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:399. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer G, James SA, Roberts IN, Oliver SG, Louis EJ. Chromosomal evolution in Saccharomyces. Nature. 2000;405(6785):451–4. doi: 10.1038/35013058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuveglise C, Feldmann H, Bon E, Gaillardin C, Casaregola S. Genomic evolution of the long terminal repeat retrotransposons in hemiascomycetous yeasts. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):930–43. doi: 10.1101/gr.219202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellinghaus D, Kurtz S, Willhoeft U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loytynoja A, Goldman N. Phylogeny-aware gap placement prevents errors in sequence alignment and evolutionary analysis. Science. 2008;320(5883):1632–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1158395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1586–91. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huerta-Cepas J, Serra F, Bork P. ETE 3: Reconstruction, analysis, and visualization of phylogenomic data. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(6):1635–8. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scannell DR, Zill OA, Rokas A, Payen C, Dunham MJ, Eisen MB, Rine J, Johnston M, Hittinger CT. The awesome power of yeast evolutionary genetics: New genome sequences and strain resources for the Saccharomyces sensu stricto genus. G3. 2011;1(1):11–25. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fink G, Boeke J, Garfinkel D. The mechanism and consequences of retrotransposition. Trends Genet. 1986;2:118–23. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(86)90200-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liti G, Carter DM, Moses AM, Warringer J, Parts L, James SA, Davey RP, Roberts IN, Burt A, Koufopanou V, Tsai IJ, Bergman CM, Bensasson D, O’Kelly MJT, Oudenaarden Av, Barton DBH, Bailes E, Nguyen AN, Jones M, Quail MA, Goodhead I, Sims S, Smith F, Blomberg A, Durbin R, Louis EJ. Population genomics of domestic and wild yeasts. Nature. 2009;458(7236):337–41. doi: 10.1038/nature07743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson MG, Linheiro RS, Bergman CM. McClintock: an integrated pipeline for detecting transposable element insertions in whole-genome shotgun sequencing data. G3. 2017;7:2749–62. doi: 10.1534/g3.117.043893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsit S, Mena A, Bigey F, Sauvage F-X, Couloux A, Guy J, Legras J-L, Barrio E, Dequin S, Galeote V. Evolutionary advantage conferred by an eukaryote-to-eukaryote gene transfer event in wine yeasts. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(7):1695–707. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cliften P, Sudarsanam P, Desikan A, Fulton L, Fulton B, Majors J, Waterston R, Cohen BA, Johnston M. Finding functional features in Saccharomyces genomes by phylogenetic footprinting. Science. 2003;301(5629):71–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1084337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okuno M, Kajitani R, Ryusui R, Morimoto H, Kodama Y, Itoh T. Next-generation sequencing analysis of lager brewing yeast strains reveals the evolutionary history of interspecies hybridization. DNA Res. 2016;23(1):67–80. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsv037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C, Li Q, Niu C, Zheng F, Li Y, Zhao Y, Yin X. Genome sequence of the lager-brewing yeast Saccharomyces sp. strain M14, used in the high-gravity brewing industry in China. Genome Announc. 2017;5(43):e01194–17. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01194-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borneman AR, Pretorius IS. Genomic insights into the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex. Genetics. 2015;199(2):281–91. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.173633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Libkind D, Hittinger CT, Valerio E, Goncalves C, Dover J, Johnston M, Goncalves P, Sampaio JP. Microbe domestication and the identification of the wild genetic stock of lager-brewing yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(35):14539–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105430108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker E, Wang B, Bellora N, Peris D, Hulfachor AB, Koshalek JA, Adams M, Libkind D, Hittinger CT. The genome sequence of Saccharomyces eubayanus and the domestication of lager-brewing yeasts. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(11):2818–31. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peris D, Langdon QK, Moriarty RV, Sylvester K, Bontrager M, Charron G, Leducq J-B, Landry CR, Libkind D, Hittinger CT. Complex ancestries of lager-brewing hybrids were shaped by standing variation in the wild yeast Saccharomyces eubayanus. PLOS Genet. 2016;12(7):1006155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liti G, Barton DBH, Louis EJ. Sequence diversity, reproductive isolation and species concepts in Saccharomyces. Genetics. 2006;174(2):839–50. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.062166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doniger SW, Kim HS, Swain D, Corcuera D, Williams M, Yang S-P, Fay JC. A catalog of neutral and deleterious polymorphism in yeast. PLOS Genet. 2008;4(8):1000183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muller LAH, McCusker JH. A multi-species based taxonomic microarray reveals interspecies hybridization and introgression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9(1):143–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strope PK, Skelly DA, Kozmin SG, Mahadevan G, Stone EA, Magwene PM, Dietrich FS, McCusker JH. The 100-genomes strains, an S, cerevisiae resource that illuminates its natural phenotypic and genotypic variation and emergence as an opportunistic pathogen. Genome Res. 2015;25(5):762–74. doi: 10.1101/gr.185538.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almeida P, Barbosa R, Bensasson D, Goncalves P, Sampaio JP. Adaptive divergence in wine yeasts and their wild relatives suggests a prominent role for introgressions and rapid evolution at noncoding sites. Mol Ecol. 2017;26(7):2167–82. doi: 10.1111/mec.14071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peter J, Chiara MD, Friedrich A, Yue J-X, Pflieger D, Bergström A, Sigwalt A, Barre B, Freel K, Llored A, Cruaud C, Labadie K, Aury J-M, Istace B, Lebrigand K, Barbry P, Engelen S, Lemainque A, Wincker P, Liti G, Schacherer J. Genome evolution across 1011 Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates. Nature. 2018;556:339–44. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0030-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naumov GI, Naumova ES, Hagler AN, Mendonca-Hagler LC, Louis EJ. A new genetically isolated population of the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex from Brazil. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1995;67(4):351–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00872934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naumov GI, James SA, Naumova ES, Louis EJ, Roberts IN. Three new species in the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex: Saccharomyces cariocanus, Saccharomyces kudriavzevii and Saccharomyces mikatae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50 Pt 5:1931–42. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-5-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almutawa Q. Impact of Chromosomal Translocations (CTs) on reproductive isolation and fitness in natural yeast isolates. PhD thesis, University of Manchester. 2016. https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/item/?pid=uk-ac-man-scw:307192. Accessed 7 June 2018.

- 45.Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, Salzberg SL. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5(2):12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nattestad M, Chin C-S, Schatz MC. Ribbon: Visualizing complex genome alignments and structural variation. bioRxiv. 2016;:082123. https://doi.org/10.1101/082123. Accessed 7 June 2018.

- 47.Almeida P, Goncalves C, Teixeira S, Libkind D, Bontrager M, Masneuf-Pomarede I, Albertin W, Durrens P, Sherman DJ, Marullo P, Todd Hittinger C, Goncalves P, Sampaio JP. A Gondwanan imprint on global diversity and domestication of wine and cider yeast Saccharomyces uvarum. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4044. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peris D, Sylvester K, Libkind D, Gonçalves P, Sampaio JP, Alexander WG, Hittinger CT. Population structure and reticulate evolution of Saccharomyces eubayanus and its lager-brewing hybrids. Mol Ecol. 2014;23(8):2031–45. doi: 10.1111/mec.12702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson HA, Pinharanda A, Bensasson D. Summer temperature can predict the distribution of wild yeast populations. Ecol Evol. 2016;6(4):1236–50. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sampaio JP, Goncalves P. Natural populations of Saccharomyces kudriavzevii in Portugal are associated with oak bark and are sympatric with S, cerevisiae and S. paradoxus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(7):2144–52. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02396-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hou J, Friedrich A, de Montigny J, Schacherer J. Chromosomal rearrangements as a major mechanism in the onset of reproductive isolation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Biol. 2014;24(10):1153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(2):511–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ty content in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus PacBio assemblies. Numbers of full-length elements (both LTRs and internal region present with > 95% coverage of canonical internal region), truncated elements (internal region present with < 95% coverage of canonical internal region), or solo LTRs (no match to internal region) were identified using a RepeatMasker (version 4.0.5) based strategy and a custom library of Ty elements from [11] supplemented with S. paradoxusTsu4. (TSV 1.20 kb)

Coordinates of Ty elements in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus PacBio assemblies. Zip file of BED-formatted genome annotations for 12 strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus with PacBio assemblies. Full-length elements (f), truncated elements (t), or solo LTRs (s) were identified using a RepeatMasker (version 4.0.5) based strategy and a custom library of Ty elements from [11] supplemented with S. paradoxusTsu4. (ZIP 91.1 kb)

Summary of complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 sequences identified in Saccharomyces whole genome assemblies at NCBI. Accession number and coordinates of 12 complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 elements identified by BLAST in 392 Saccharomyces (taxid: 4930) WGS assemblies at NCBI that had high similarity (> 80% coverage and > 80% identity) to the Tsu4 query sequence (Genbank: AJ439550). (CSV 1.77 kb)

Multiple sequence alignment of Ty4 and Tsu4 elements in Saccharomyces sensu stricto species. Multiple sequence alignment of all full-length Ty4/Tsu4 elements from 12 strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus with PacBio assemblies from Yue et al. [13] plus all complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 elements identified in Saccharomyces WGS assemblies at NCBI (> 80% coverage and > 80% identity relative to the Tsu4 query sequence from S. uvarum). Fasta files of Ty4/Tsu4 sequences from all strains plus the Ty4 and Tsu4 query sequences were concatenated together and aligned using MAFFT (version 7.273-e; options: –thread 28) [52]. (TXT 335 kb)

Maximum likelihood tree file for Ty4 and Tsu4 elements in Saccharomyces sensu stricto species. Newick-formatted file of the maximum-likelihood tree of all full-length Ty4/Tsu4 elements from 16 strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus plus all complete or nearly-complete Tsu4 elements identified in Saccharomyces WGS assemblies at NCBI. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis was performed on the multiple alignment in Additional file 4 using RAxML (version: 8.2.4; options -T 28 -f a -x 12345 -p 12345 -N 100 -m GTRGAMMA) [28] excluding positions 1-166 and 6086-6476. (TXT 3.79 kb)

Coordinates of best-matches to scaffolds from S. pastorianus and Saccharomyces sp. M14 containing Tsu4 sequences vs. a pan-genome of S. eubayanus and S. cerevisiae genomes. S. pastorianus and Saccharomyces sp. M14 scaffolds were aligned to a pan-genome composed of scaffolds from S. eubayanus FM1318 (Genbank: GCF_001298625.1) and chromosomes from S. cerevisiae S288c (from [13]). Alignments were generated using nucmer (default parameters), delta-filter (options: -1 -l 2000), and show-coords (options: -lTH) in mummer 3.23 [45]. (TSV 5.15 kb)

Dot-plot of the Chinese lager strain Saccharomyces sp. M14vs. a pan-genome of S. eubayanus and S. cerevisiae genomes. Dot-plot of Saccharomyces sp. M14 scaffolds aligned to a pan-genome composed of scaffolds from S. eubayanus FM1318 (Genbank: GCF_001298625.1) and chromosomes from S. cerevisiae S288c (from [13]), showing that Saccharomyces sp. M14 contains subgenomes from both species and that this strain may be a previously-unidentified strain of the lager brewing species S. pastorianus. The dot-plot was generated using nucmer (default parameters) and mummerplot (options: --size large -fat --color -f --png) in mummer 3.23 [45]. (PDF 58.8 kb)

Dot-plot of the S. pastorianus group 2/Frohberg strain W34/70 vs. a pan-genome of S. eubayanus and S. cerevisiae genomes. Dot-plot of S. pastorianus group 2/Frohberg strain W34/70 scaffolds aligned to a pan-genome composed of scaffolds from S. eubayanus (Genbank: GCF_001298625.1) and chromosomes from S. cerevisiae (S288c from [13]), showing that S. pastorianus group 2/Frohberg strain W34/70 contains subgenomes from both species in a similar pattern as for Saccharomyces sp. M14 (see Additional file 7). The dot-plot was generated using nucmer (default parameters) and mummerplot (options: --size large -fat --color -f --png) in mummer 3.23 [45]. (PDF 69.8 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Canonical LTR and annotated internal sequences for S. paradoxusTsu4 have been submitted to Repbase. All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.