Condensed Abstract

Fear of recurrence (FoR) has been well documented among cancer survivors, yet there have been few publications on strategies for coping with FoR. This report describes three coping strategies tailored to the management of FoR and the delivery of these coping strategies through FoRtitude, a targeted eHealth intervention deigned to teach breast cancer survivors coping strategies targeted to FoR using a web- and text messaging-based approach.

Fear of recurrence (FoR) is very common among cancer survivors.1 As many as 22-87% experience moderate to severe FoR.2 FoR has been associated with more global psychological distress, impairments in quality of life, and increased health-care utilization.3 Long-term cancer survivors have identified help with managing FoR as their most pressing unmet need.4 However, there are very few publications on the clinical management of FoR and interventions targeting FoR have yet to be empirically evaluated.

In her clinical practice, Wagner adapted cognitive behavior therapy techniques to teach cancer survivors strategies for managing FoR. Anecdotally based on her clinical experience, cancer survivors were motivated to learn these coping strategies, which were effective in reducing FoR. Our study team then developed and evaluated “FoRtitude”, an eHealth intervention designed to reduce FoR among breast cancer survivors through teaching these coping strategies. The use of an eHealth approach overcomes barriers to psychosocial care, including access to care and cost. This report describes our approach to the clinical management of FoR using patient education and coping strategies based in cognitive behavioral principles and our translation of these techniques into a format for eHealth delivery. We also include a brief description of our use of an innovative methodological approach to evaluate FoRtitude. Results from our randomized trial evaluating FoRtitude will be reported in the future.

Clinical Management of FoR

Currently, there are no published evidence-based psychosocial interventions for FoR. FoR shares some features with anxiety disorders that, even at subclinical levels, can compromise emotional well-being (eg. rumination, excessive worry, intrusive thoughts). Given similarities, interventions for anxiety disorders with shared features, including Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, hold potential for FoR. Relevant intervention techniques include relaxation training, cognitive restructuring (“changing how you feel by changing how you think”), and scheduled worry practice (“get control over your worry about recurrence by scheduling when and where it happens”). Wagner employed these techniques in clinical practice and found each coping strategy to be effective in reducing FoR. FoRtitude was developed to teach cancer survivors these techniques via the web. In the following sections, we provide a description of how to adapt each coping strategy to the management of FoR, as well as our adaption for eHealth delivery via FoRtitude.

Development of FoRtitude: Description of the eHealth intervention

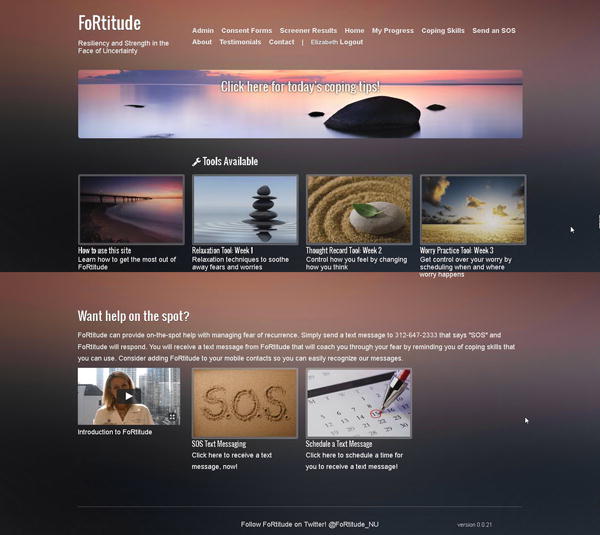

The FoRtitude web-site was designed with the goal of translating clinician-taught coping strategies to an eHealth format. The FoRtitude web-site included didactic content to educate survivors on topics that are important to the successful use of coping strategies that were being taught, including the rationale for using the coping strategy which is critical for promoting adherence and instructions on how to use each coping strategy. The FoRtitude site included an interactive tool paired with each coping strategy to promote application of the coping technique. Didactic content and interactive tools were delivered through text-based lessons and videos. We incorporated graphic images throughout the web-site to enhance aesthetics of the site, using images to promote a feeling of health and well-being (see Figure 1 for FoRtitude screen shot). FoRtitude also included an interactive text messaging feature for the immediate delivery of reminders of how to use coping strategies taught through the site when cancer survivors were unable to access the internet.

Figure 1.

FoRtitude home page screen shot. The images featured on the home page were purchased and downloaded from iStock photos 8/20/2013.

FoRtitude content

The FoRtitude web-site included introductory content on FoR, along with a description of features of the FoRtitude site and recommendations for how to use the FoRtitude site to maximize potential benefit. In very general terms, FoRtitude introductory content was comparable to an initial visit with an anxious patient, during which the clinician shares his or her conceptualization of anxiety and the rationale for teaching coping strategies for anxiety management. The FoRtitude introductory content included: (1) education on FoR, including cognitive and emotional features; (2) a description of features of the FoRtitude site, and (3) a rationale for using the FoRtitude site regularly for a brief time-limited period. Education on FoR reviewed cognitive features, including worry, rumination, and intrusive thoughts about recurrence. Survivors were encouraged to view these thoughts about recurrence as a common, understandable response to a stressful life event (ie. having cancer), and that these thoughts are associated with the emotional features of FoR, including fear, anxiety, and uncertainty. Educational content emphasized that FoRtitude would teach healthy strategies for coping with the cognitive and emotional features of FoR.

Cancer survivors were encouraged to use the FoRtitude site daily or a minimum of 3-4 times per week to read new didactic content (released every 3 days) and to use interactive tools to promote the mastery of coping strategies. This is comparable to “homework” assigned in clinical practice, a commonly used technique to promote the use of newly learned coping strategies.

Based in Wagner’s clinical practice, three coping strategies were found to have benefit in reducing FoR and were taught through FoRtitude: Relaxation, Cognitive restructuring, and Worry Practice. Each CSM consists of two didactic lessons and one interactive tool. Didactic lessons were presented as paragraphs of text, occasionally accompanied by illustrative graphics, which could be paged through in 10-15 screens, tailored to use of the CSM for the management of FoR. Interactive tools were tailored to each CSM and promoted the application of each CSM for the management of FoR. For each CSM the first didactic lesson explained the rationale for using the CSM to manage FoR and described the CSM, then the interactive tool was provided. The second didactic lesson focused on application of the CSM for FoR, including recommendations for how to incorporate CSMs on a long-term basis. Links to each of the interactive tools were available in a salient location on the FoRtitude home page, as shown in Figure 1. Each tool was represented on the home page with an aesthetically pleasing image accompanied by the tool’s title and brief description, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of FoRtitude Interactive tools

| Coping strategy | Description on FoRtitude site | Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Relaxation | Relaxation Tool: Relaxation techniques to soothe away fears and worries | Audio-recordings of imagery based relaxation, progressive muscle relaxation, and autogenic relaxation |

| Cognitive restructuring | Thought record tool: Control how you feel by changing how you think | Thought record |

| Scheduled worry practice | Worry practice tool: Get control over your worry by scheduling when and where worry happens | Video-guided (10 minutes) or self-guided (5, 10, 15, or 30 minute) worry practice session |

Relaxation exercises

Diaphragmatic breathing and relaxation exercises are widely used for the management of anxiety to reverse the physiological effects of anxiety and stress. This coping technique is highly valuable for the management of FoR, given that thoughts of cancer recurrence are frequently accompanied by physiological hyperarousal, which can be effectively managed through diaphragmatic breathing and relaxation. Through FoRtitude, the first Relaxation lesson educated participants on the physiological effects of anxiety and presented diaphragmatic breathing and relaxation as strategies to reverse the physiological effects of anxiety. The Relaxation interactive tool included audio-recordings of autogenic relaxation, imagery-based relaxation, and progressive muscle relaxation exercises. On the FoRtitude site, the Relaxation tool icon included a brief description “Relaxation techniques to soothe away fears and worries.” Relaxation audio-recordings varied in length from 5-20 minutes and included recordings in male and female voices. The tool included a feature that allowed participants to rate anxiety and stress before and after listening to audio-recordings and ratings could be saved to allow participants to keep a record of relaxation practice. The second relaxation lesson provided strategies for implementing diaphragmatic breathing and relaxation practice into daily life, including instructions for “mini” relaxation breaks. In addition to the therapeutic value in managing FoR, the authors’ prior eHealth intervention research has found that the provision of relaxation training enhances intervention adherence, which can be a challenge for eHealth-based interventions.

Cognitive restructuring

Cognitive restructuring is a cognitive behavioral technique that involves learning to identify maladaptive thoughts, particularly thoughts associated with increased anxiety, and replacing them with more accurate, healthier thoughts. Based on clinical experience, FoR is often driven by the underlying cognition that worry about recurrence may affect the outcome (eg. “if I expect a recurrence, at least I won’t be caught off guard and I’ll be prepared.”) FoRtitude’s first Cognitive restructuring lesson explained a basic tenant of the cognitive behavioral model, that cognitions underlie emotions and difficult emotions (eg. anxiety) can be managed through thinking about things differently (ie. altering one’s cognitions). The first Cognitive restructuring lesson reviewed cognitions that commonly underlie anxiety and worry, including worry about recurrence, and strategies for changing anxiety-generating cognitions. The Cognitive restructuring tool was designed as a thought record worksheet, a commonly-used tool in cognitive behavioral interventions. On the FoRtitude site, this tool was called the “Thought record tool” with a brief description “Control how you feel by changing how you think.” This tool consisted of an interactive worksheet that asked participants to document a brief description of a recent upsetting event, the accompanying emotion (selected from a drop-down menu), and accompanying cognitions. Participants identified a cognitive distortion from a drop-down menu and were encouraged to generate alternative cognitions (free text, with examples provided). The FoRtitude site provided the following example: “…the alternative thought ‘I’m doing everything I can to prevent a recurrence’ is much more powerful than saying ‘I just have to tell myself I won’t have cancer again.” Participants were able to save completed thought records, including free text entered by participants to describe anxiety-provoking events and cognitions, and pre- and post-anxiety ratings. The second Cognitive restructuring lesson reinforced the potential benefits from challenging anxiety-generating thoughts and identifying alternative cognitions including many examples focused on FoR-related cognitions and alternative thoughts.

Scheduled worry practice

Scheduled worry practice is a cognitive behavioral technique designed to encourage actively thinking about the feared event (ie. cancer recurrence) to reduce avoidance and engage healthy coping strategies, such as problem-solving (eg. “if I have cancer again I’ll work with my oncology team to treat it”). Additionally this coping strategy teaches cancer survivors that they can think about having a recurrence, without catastrophic outcomes, increasing confidence in survivors’ ability to manage FoR. The rationale for this coping strategy is that it provides cancer survivors with greater control over FoR through scheduling when and where worry happens. The process of actively thinking about recurrence can be daunting. In clinical practice, scheduled worry often is conducted in-session with the psychosocial provider. Scheduled worry practice provides structure through a defined start and stop for this exercise. On the FoRtitude site, the first Worry Practice lesson emphasized the rationale for scheduled worry practice (ie. “you’re worrying about recurrence already so why not decide when and where worry happens?”). The FoRtitude worry practice lesson discussed the association between avoidance and increased anxiety, and reviewed instructions for this technique. The Worry Practice tool was designed to facilitate scheduled worry practice for a pre-determined period of time (5, 10 or 15 minutes) during which participants were instructed to focus exclusively on worries about recurrence. The tool included a timer and a free text box to type in worries and thoughts. The tool included graphics (large stop sign and a release button to ‘release’ worries) which appeared at the end of the worry practice to encourage participants to stop focusing on worry once the practice session was complete. Survivors were then instructed to cope with intrusive thoughts about recurrence by reminding themselves they would focus on these thoughts at the next scheduled worry practice. Given that this coping strategy is somewhat counter-intuitive and challenging for some, a video-based version of the worry practice tool was also available to guide participants through the worry practice exercise in an attempt to approximate an in-session worry practice exercise. Through use of the Worry practice tool (video- or self-guided), participants were coached through the process of focusing on worry about recurrence for a pre-determined amount of time. This was followed by instructions to release worries. The second Worry practice lesson reviewed strategies for confining worry to scheduled worry practice sessions and reinforced actively facing thoughts of recurrence over avoidance, as an effective coping technique (eg. “it is much easier to cope with fears when you bring them into the light of day”).

Text messaging

The FoRtitude site included an “SOS” feature to provide immediate reminders of strategies to cope with fear of recurrence (eg. “remember that worrying about recurrence does not give you control over the future”). Participants could receive text messages to reinforce FoRtitude coping strategies through sending a text message to FoRtitude or through requesting an immediate or scheduled text message through the FoRtitude site. For example, participants could schedule text messages for delivery on days with scheduled follow-up medical visits to promote the application of coping strategies taught through FoRtitude to anxiety-generating situations.

Use of the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) to evaluate FoRtitude

We conducted a randomized trial to evaluate FoRtitude using an innovative methodological approach, MOST.5,6 This design allows us to evaluate the effectiveness of each coping strategy in reducing FoR. Results will be presented in the future.

Summary

In this brief report, we have described three coping strategies tailored to the management of FoR. We described the adaptation of these coping strategies for delivery via an eHealth format to overcome barriers to psychosocial care and to empirically evaluate each coping strategy. While our clinical experience indicates these strategies are effective in reducing FoR and associated distress, the results of our trial evaluating FoRtitude are forthcoming. In light of our clinical success with these coping strategies, oncology providers should consider referring patients with moderate to severe FoR for brief intervention to psychosocial providers with expertise in these cognitive behavioral techniques. Alternatively, oncology providers may recommend commercially available resources to teach relaxation techniques including web-based relaxation audio-recordings (eg. www.healthjourneys.com) and patient workbooks which teach similar coping strategies (eg. “Little ways to keep calm and carry on”7, “Relaxation and stress reduction workbook”8). While advances in cancer therapy and genomic profiling have significantly increased our ability to predict outcomes, no cancer survivor can be guaranteed a future free of cancer. Therefore, the goal in treating FoR is to bolster survivors’ confidence in their ability to manage the physical and emotional facets of cancer survivorship, including FoR, through promoting the use of healthy coping strategies.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support

This project was funded by the National Cancer Institute (1R21 CA173193)

Biographies

Lynne I. Wagner, Ph.D. is [TK].

Jenna Duffecy, Ph.D. is [TK].

Frank Penedo, Ph.D. is the Roswell Park Professor of Medical Social Sciences, Psychology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Feinberg School of Medicine and Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences of Northwestern University. He is the program leader for the Cancer Control and Survivorship research program and the director of the Cancer Survivorship Institute at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. He is the current President of the International Society of Behavioral Medicine, a Fellow of the Society of Behavioral Medicine and a member of the Academy of Behavioral Medicine Research.

David C. Mohr, Ph.D. is a Professor of Preventive Medicine and Director of the Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies in the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. He is a fellow of the American Psychological Association and the Society for Behavioral Medicine, and was a founding board member for the International Society for Research in Internet Interventions.

David Cella, Ph.D. is the Ralph Seal Paffenbarger Professor and Chair of the Department of Medical Social Sciences at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Dr. Cella developed and is continually refining the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System for outcome evaluation in patients with chronic medical conditions. He was steering committee chair and principal investigator of the statistical coordinating center for the NIH Roadmap Initiative to build a Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS).

References

- 1.Lee-Jones C, Humphris G, Dixon R, Bebbington Hatcher M. Fear of Cancer Recurrence — A Literature Review and Proposed Cognitive Formulation to Explain Exacerbation of Recurrence Fears. Psycho-Oncology. 1997;6(2):95–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199706)6:2<95::AID-PON250>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–322. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thewes B, Butow P, Bell ML, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviours. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(11):2651–2659. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, et al. Patients’ Supportive Care Needs Beyond the End of Cancer Treatment: A Prospective, Longitudinal Survey. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6172–6179. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins L, Murphy S, Nair V, Strecher V. A strategy for optimizing and evaluating behavioral interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2005;1(30):65–73. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins LM, Dziak JJ, Kugler KC, Trail JB. Factorial experiments: efficient tools for evaluation of intervention components. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinecke M. Little ways to keep calm and carry on. New Harbinger Publications, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis M, Eshelman ER, McKay M. Relaxation and stress reduction workbook. New Harbinger Publications, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]