Abstract

Background:

Toothbrushes are an important medium for maintaining good oral hygiene, and hence there arises a need to maintain and replace toothbrushes at a regular interval. Assessing the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of the medical and dental interns would help the society in promoting oral hygiene in a broader aspect.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional questionnaire study was conducted among 759 medical and dental interns residing in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. The data on oral health KAP were collected using a self-structured questionnaire. Descriptive statistics was evaluated using SPSS software package, version 19.

Results:

Of 759 participants, 445 were dental interns and 314 were medical interns. Knowledge about toothbrush maintenance was seen to be more in the dental interns. The attitude toward maintenance was seen to be better among the dental interns compared with the medical interns. The practice of toothbrush maintenance was seen in both the groups but more dominantly in the dental interns.

Conclusion:

Education regarding the effective use and maintenance of the toothbrush would help improve the KAP toward toothbrush maintenance and replacement. The lack of knowledge holds back the attitude of properly maintaining the toothbrush in a regular basis.

KEYWORDS: Dental, medical, toothbrush

INTRODUCTION

Toothbrushes are an important medium for maintaining good oral hygiene and are commonly found in both community and hospital setting. Toothbrushes may play a significant role in disease transmission and increase the risk of infection because they can serve as a reservoir for microorganisms in healthy, oral-diseased, and medically ill adults.[1] In healthy adults, contamination of toothbrushes occurs early after initial use and increases with repeated use.[2,3] Toothbrushes can become contaminated from the oral cavity, environment, hands, aerosol contamination, and storage containers. Bacteria that attach to, accumulate, and survive on toothbrushes may be transmitted to the individual causing diseases such as dental caries, gingivitis, periodontitis, and stomatitis.[4,5] Knowledge about toothbrush maintenance and replacement plays a major role in portraying a good oral hygiene. The attitude toward properly maintaining the toothbrush is proportionate to the lack of awareness among the public. The American Dental Association recommends changing of toothbrush every 3–4 months depending on the fraying of the toothbrush bristles. The contamination or the ill-effects of not maintaining toothbrush well has not been mentioned. The depth of knowledge is important for anyone to practice an act. Dentists play an important role in suggesting effective oral hygiene maintenance aids for maintenance of good oral health, but there is a lack of evidence where maintenance of aids is mentioned. The medical professionals also serve as a mode in the promotion of oral health, and hence it is equally important to access the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of the medical interns. The dental students’ attitudes and health beliefs as future dentists not only influence their oral self-care habits but also potentially improve their patients’ ability to take care of their teeth, thus improving overall oral health knowledge.[6,7] Studies have shown that oral health education and promotion can increase an individual’s knowledge about oral health and can change attitudes toward it, thus improving behavior.[8] Hence, this study aimed to assess and compare the differences in the KAP among young interns in the maintenance and replacement of toothbrush. Analyzing and then inducting the interns in this study would help in the improvement of the society’s Knowledge as they serve to be the primary health providers. This would be beneficial in providing a platform to improve oral hygiene practices among the people of the society.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional, descriptive, questionnaire-based survey method was taken up to assess the KAP level regarding the toothbrush maintenance and replacement among the medical and dental intern population in Bhubaneswar city. The ethical committee approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee, Kalinga Institute of Dental Sciences University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. A pilot study was conducted with n = 50, before sample selection. The absolute precision was found to be 5%, and the confidence level was attained to be 95%. The sample size was derived to be 759. A total of 314 medical and 445 dental students undergoing internship in the medical and dental colleges in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, willingly volunteered for participating in the study. This study was conducted over a period of 3 months. The participants were informed before the commencement of the study, and a written informed consent was obtained from all of them. The entire population of medical and the dental interns were taken up for the study. The subjects were divided into two different groups: first group consisting of the medical interns and the second group consisting of the dental interns. The subjects who were pursuing the rotatory posting and present in the college premises during the time of the study were included. The subjects who were not willing were excluded from the study. The questionnaires were distributed in the work places and collected within the same session.

A validated self-administered questionnaire was distributed among the eligible participants. The questionnaire comprised a sociodemographic section and questions related to the KAP toward toothbrush maintenance and replacement. The questionnaire was prepared in English and comprised 19 multiple-choice questions. The face validity of the questionnaire was tested by distributing it among the students posted in the department of public health dentistry at that period. The time required to fill the questionnaire was assessed, and accordingly modifications in the questionnaire were carried out. The content validation was carried out by distributing the questionnaire among the expert panel that was formed by the faculty members of the department. The questionnaire was finalized to six knowledge-based questions (questions 1–6), seven attitude-based questions (questions 7–13), and six practice-based questions (questions 14–19). For the purpose of analysis, each correct answer was given score “one,” and wrong answer was given score “zero” in the items included in the questionnaire. Overall, group and individual scores on the questions were based on the number of correct answers.

Test–retest method (Cronbach’s α = 0.87) was used to measure the reliability. The results were hypothesized with response scores that significantly related to the level of KAPs regarding toothbrush maintenance and replacement among the study participants.

The data were transferred from precoded pro forma to a computer through a master chart, which was created for the purpose of data analysis. The obtained results were statistically evaluated using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 19 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA), Pearson’s chi-square, mean, and standard deviation for continuous variables were obtained. Results were evaluated using descriptive statistical analysis. The P-value was kept to be 0.05; <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Microsoft Word and Excel sheet were used to generate tables and graphs.

RESULTS

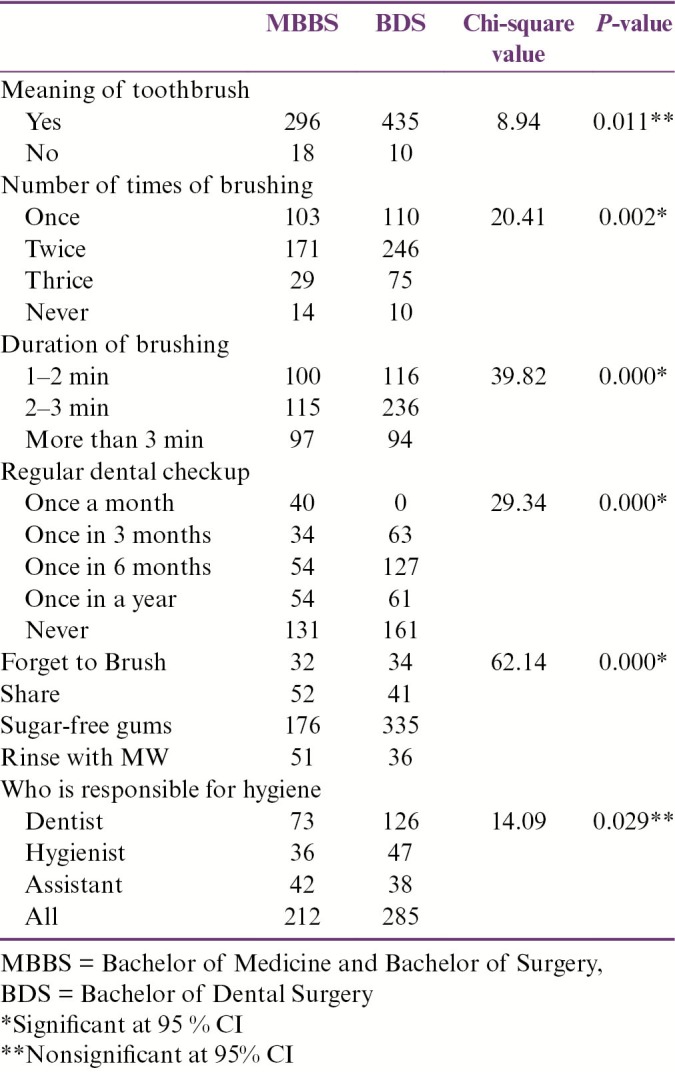

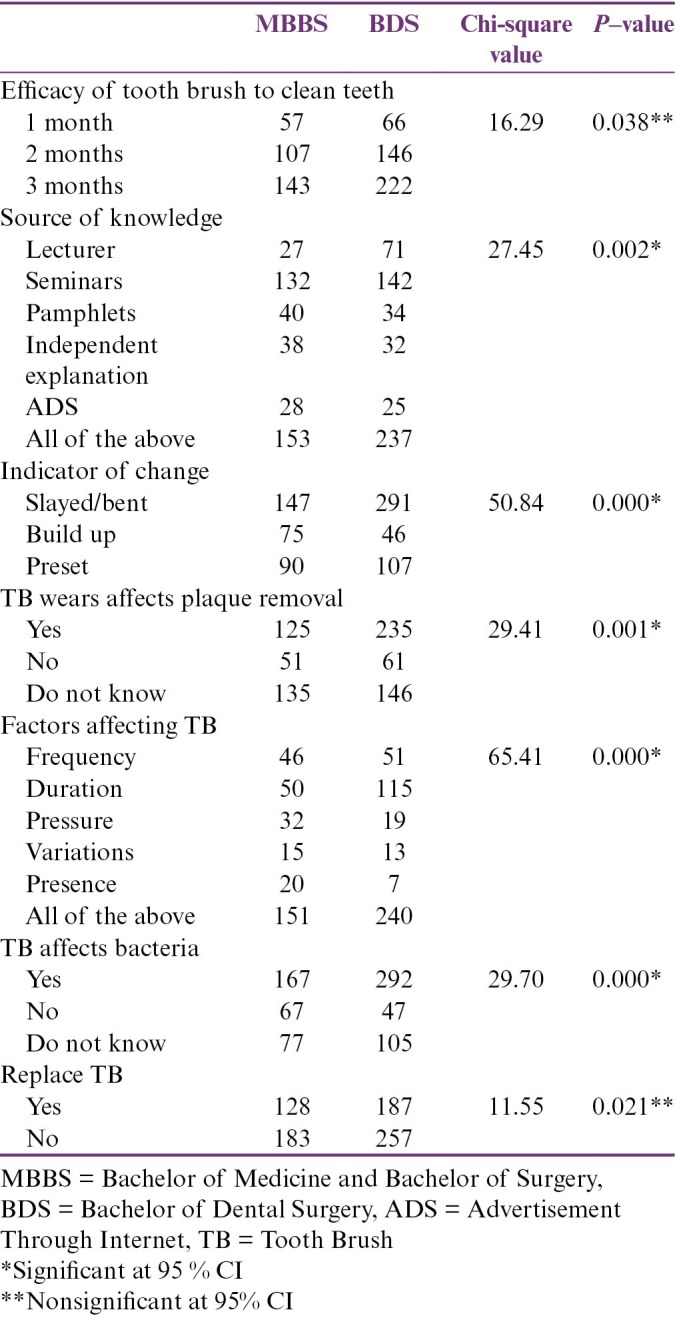

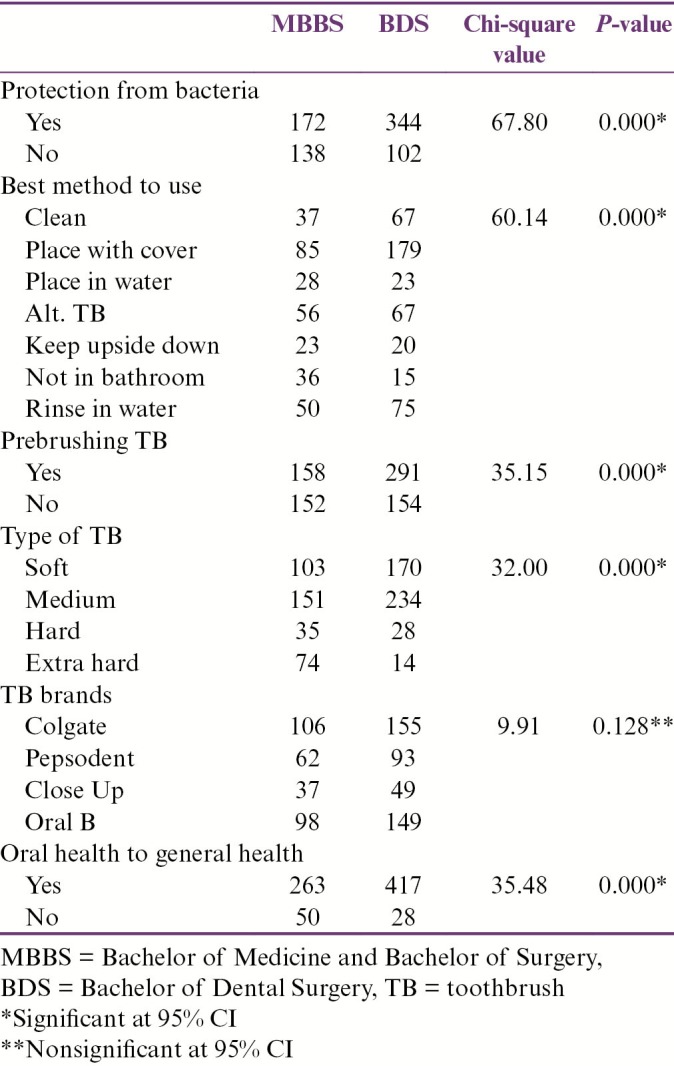

In the aforementioned study, the KAP of 759 interns, 445 dental and 314 medical interns, of the Bhubaneswar city toward toothbrush use and maintenance was accessed [Figure 1]. A varied response was observed regarding the toothbrush maintenance and replacement among the dental and medical interns. This study being a questionnaire-based study, a set of 19 questions were used to find the KAP of the subjects in maintaining a toothbrush and replacing it after wear. Significant results were obtained with questions pertaining to the knowledge of the participants about the duration of brushing, regular dental checkup, and forgetting to brush [Table 1]. The dental interns had a better knowledge as compared to the medical interns. In contrast, the medical interns were seen to use mouthwash more as compared to the dental professionals. While analyzing the attitude of the interns, significant results were found in the questions relating to the source of knowledge regarding the oral hygiene maintenance, indicator for changing the toothbrush, whether plaque removal is affected or not, the factors affecting the toothbrush wear, and the toothbrush is being affected by bacteria [Table 2]. The medical interns have been found to believe more that the dental assistants were responsible for the education of the patient. The mean scores of the practice-related questions show type of toothbrush used, relation of oral health to general health, and the toothbrush brands used by them. Here again the dental interns had better scores than the medical interns [Table 3].

Figure 1.

Distribution of the study subjects according to their qualification

Table 1.

Responses of study subjects based on knowledge about toothbrush and oral hygiene

Table 2.

Responses of study subjects based on attitude toward toothbrush

Table 3.

Responses of study subjects based on practice toward toothbrush maintenance

DISCUSSION

Oral hygiene has been identified as the predominant and inevitable component of preventing oral diseases, including gingivitis and periodontitis, for which various mechanical and chemical oral hygiene aids have been framed. Utilization of these oral hygiene practices augments the successful maintenance of the oral health. A good oral hygiene and oral health directly depends on the frequency and duration of toothbrushing.

A quantitative research method has been taken up in this project. A self-administered questionnaire has been used to gather data concerning KAP among the medical and dental interns in Bhubaneswar city. Maximum number of the participants had fair knowledge regarding the toothbrush. They were quite educated regarding the frequency of brushing, and it was seen that most of the participants brushed twice daily. Studies have stated that for efficient cleaning of the tooth, it has been recommended that the subjects brush twice daily[9] although brushing once with strict methods was beneficial as well. This was so because the methods adopted for brushing was not ideally maintained by the subjects. The World Health Organization recommends a regular dental checkup in an interval of 6 months for proper maintenance of the oral hygiene, but the participating subjects were not found to be reluctant in attending the dental office when they had no dental problems. Various methods were adopted for the education of the subjects. A study conducted by Abraham et al.[7] stated that the medical or the dental practitioners were well aware of the toothbrush contamination by microorganisms. They were clear about changing their toothbrush in a span of 2–3 months.[10,11,12] Some among them changed once the bristles were seen to be flared. The replacement of the toothbrushes should be on a periodic basis, although the amount of visible bristle wear does not appear to affect plaque removal for up to 9 weeks.[13]

It has been shown in various studies that toothbrushes are subjected to contamination by the contact with the environment, and the survival of the bacteria is affected by the containers the toothbrush is stored. Dayoub et al.[14] found that toothbrushes placed in closed containers and exposed to contaminated surfaces yielded higher bacterial counts than those left open to air. Mehta and Bachmann[15] found that the use of a cap for toothbrush storage increased bacteria survival. Glass[16] found that increase in the humidity of the environment was directly related to the bacterial survival on toothbrushes. In addition, Glass[16] also found that bacteria survived more than 24h in presence of moisture. They had little knowledge about the use of premedicated mouthwash before brushing and the correlation of effective brushing. Mehta & Bachmann[15] in their study have found that an overnight immersion of the toothbrush in the Chlorhexidine gluconate solution can reduce the contamination & microbial load on the toothbrush thereby helping in the long term effective maintenance of it. They also suggested that Chlorhexidine was far more superior than Listerine solution for this purpose.[17,18] Sato et al.[19] found that rinsing toothbrushes with tap water resulted in continued high levels of contamination and biofilm.

A variety of toothbrushes are manufactured these days. The bristles of the toothbrushes varies from soft to hard with innumerable cluster patterns and plastic shapes whereas the handles of the toothbrush included varied plastic shapes and decorative moldings. Studies have examined various toothbrush design elements. Bunetel et al.[17] found that bacteria got trapped inside the toothbrush bristles, and survival of the bacteria was depended on the bacteria (aerobic versus anaerobic) and toothbrush design. Scholars have also found that solid handles harbored less bacteria retention and that with the increase in the surface area, the microbial load also increased. Toothbrushes with frayed bristles and closely arranged bristles together trapped and retained more bacteria.[10] Similar finding was also highlighted in a study by Glass[16] that explored the level of bacterial retention based on toothbrush brand, color, and bristle pattern. Contamination was the lowest in soft-and-round, clear, two bristle–row toothbrushes. Glass[16] also found that pathogenic bacteria adheres to plastic after short exposure times. Caudry et al.[10] found that bacteria strongly adheres to the bristles. Mehta and Bachmann[15] found that the retention of moisture and oral debris in the bristles increased bacterial survival.

There are studies on the contamination of toothbrushes, which state that toothbrushes used by healthy and oral-diseased adults usually gets contaminated with potentially pathogenic microorganisms, resulting from the dental plaque, various environmental factors, design, and other conglomeration of factors. The aforementioned study identifies the quality of knowledge that the medical and dental subjects hold regarding the contamination of the toothbrush and whether the subject is bound to change his or her toothbrush following a diseased state. Various studies have shown that in a vulnerable population such as critically ill adults, pathogenic contamination may increase the risk of infection and mortality.[15] In contrast to the aforementioned study, it has been observed that only a limited percentage of the participating population was actually aware of the various ways of contamination of the toothbrush. The increased commercialization has provoked many to use fluoridated toothpastes along with moderately hard bristles and changing the toothbrush in a frequency of 2–3 months of duration.[7,20,21] This has improved the maintenance of the highly and randomly used oral hygiene aid.

The knowledge regarding oral health being a gateway to physical health was not clearly known to all. The dental subjects were quite educated in this regard. Various other researchers are welcomed in this field, and there should be a vivid patient education regarding the well maintenance of the toothbrush among all the subjects.

CONCLUSION

There seems to be a great need to continuously promote and teach dental and medical interns about the benefits of good oral hygiene habits so that they can promote and implement them among the general population. Along with these, education regarding the effective use and maintenance of the toothbrush should be taken into account. This is because the use of toothbrush is directly related to the oral health of an individual. And the oral health is directly related to the physical well-being of the subjects. Because of the limited number of publications specifically related to toothbrush contamination, here comes a call for more number of researches directed toward this field for the betterment of the common population.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century—the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozai K, Iwai T, Miura K. Residual contamination of toothbrushes by microorganisms. ASDC J Dent Child. 1989;56:201–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verran J, Leahy-Gilmartin AA. Investigations into the microbial contamination of toothbrushes. Microbios. 1996;85:231–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svanberg M. Contamination of toothpaste and toothbrush by streptococcus mutans. Scand J Dent Res. 1978;86:412–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1978.tb00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott E, Bloomfield SF, Barlow CG. An investigation of microbial contamination in the home. J Hyg (Lond) 1982;89:279–93. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400070819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman R. The psychology of dental patient care. 5. The determinants of dental health attitudes and behaviours. Br Dent J. 1999;187:15–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham NJ, Cirincione UK, Glass RT. Dentists’ and dental hygienists’ attitudes toward toothbrush replacement and maintenance. Clin Prev Dent. 1990;12:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharda AJ, Shetty S. A comparative study of oral health knowledge, attitude and behaviour of first and final year dental students of Udaipur city, Rajasthan, India. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:347–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glass RT. The infected toothbrush, the infected denture, and transmission of disease: a review. Compendium. 1992;13:592, 594, 596–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caudry SD, Klitorinos A, Chan EC. Contaminated toothbrushes and their disinfection. J Can Dent Assoc. 1995;61:511–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daly CG, Chapple CC, Cameron AC. Effect of toothbrush wear on plaque control. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:45–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attin T, Hornecker E. Tooth brushing and oral health: how frequently and when should tooth brushing be performed? Oral Health Prev Dent. 2005;3:135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frazelle MR, Munro CL. Toothbrush contamination: a review of the literature. Nurs Res Pract 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/420630. ArticleID 420630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dayoub MB, Rusilko D, Gross A. Microbial contamination of toothbrushes. J Dent Res. 1977;56:706. doi: 10.1177/00220345770560063501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta A, Sequeira PS, Bhat G. Bacterial contamination and decontamination of toothbrush after use. NY State Dent J. 2007;73:20–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glass RT. Toothbrush types and retention of microorganisms: how to choose a biologically sound toothbrush. J Okla Dent Assoc. 1992;82:26–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunetel L, Tricot-Doleux S, Agnani G, Bonnaure-Mallet M. In vitro evaluation of the retention of three species of pathogenic microorganisms by three different types of toothbrush. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2000;15:313–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2000.150508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldschmidt MC, Warren DP, Keene HJ, Tate WH, Gowda C. Effects of an antimicrobial additive to toothbrushes on residual periodontal pathogens. J Clin Dent. 2004;15:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato S, Pedrazzi V, Guimarães Lara EH, Panzeri H, Ferreira de Albuquerque R, Jr, Ito IY. Antimicrobial spray for toothbrush disinfection: an in vivo evaluation. Quintessence Int. 2005;36:812–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leichter J, Pack AR. The attitudes of New Zealand dentists and dental hygienists towards toothbrushes and toothbrushing. J N Z Soc Periodontol. 1999;84:14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daly CG, Marshall RI, Lazarus R. Australian dentists’ views on toothbrush wear and renewal. Aust Dent J. 2000;45:254–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2000.tb00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]