Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in renal allograft recipient is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. At present, only few studies related to treatment and outcomes of HCV-infected renal allograft recipients with DAAs have been published. We aimed the study to assess the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir-based regimens in HCV-infected renal allograft recipients. We analyzed data of 22 eligible HCV-infected renal allograft recipients (14 genotype-3, 6 genotype-1, one each genotype-2 and 4) who were treated with DAAs at our institute. DAA regimen included sofosbuvir and ribavirin with or without ledipasvir or daclatasvir for 12–24 weeks. Patients were followed up for 24 weeks after completion of treatment. A rapid viral response of 91%, end of therapy response of 100%, and sustained viral response at 12 and 24 weeks of 100% with rapid normalization of liver enzymes were observed. Therapy was well tolerated except for ribavirin-related anemia. A significant decrease in tacrolimus trough levels was observed and most patients required increase in tacrolimus dose during the study. Treatment with newer DAAs is effective and safe for the treatment of HCV-infected renal allograft recipients.

Keywords: Direct-acting antiviral agents, hepatitis C virus positive, outcomes, renal transplant recipient, tacrolimus

Introduction

Renal transplantation is the treatment of choice for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection complicates both pre and post-transplantation management of these patients. HCV infection is associated with poor patient and graft survival in renal allograft recipients.[1,2,3] However, renal transplantation offers a significant survival advantage to HCV-infected ESRD patients as compared to those who remain on dialysis.[4] The present guidelines suggest that HCV-infected patients should be treated with interferon (IFN)-based therapy with or without direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) so as to achieve sustained virological response (SVR) before renal transplantation to minimize chances of post-transplant HCV progression.[5,6] In ESRD, IFN-based regimens have modest efficacy (SVR 50%–60%) and have poor tolerability resulting into high discontinuation rates (18%–25%).[5,7] A significant proportion of these patients experience relapse after transplantation.[8] Treatment with conventional or pegylated IFN in postrenal transplant period is associated with high incidence of acute rejection rates (30%–50%), and it is recommended only in life-threatening situations such as fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis.[5,9] IFN-free regimens consisting combination of DAAs have been highly effective and safe in treating liver transplant recipients having relapse of HCV infection.[10,11,12] However, there is a paucity of data regarding the use of DAAs in renal transplant patients with only few studies in literature.[13,14] The aim of present study was to report safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-based regimens used for the treatment of HCV-infected renal allograft recipients.

Materials and Methods

All HCV-infected renal allograft recipients (n = 68/1254, 5.4%) who underwent renal transplantation at our institute between January 2005 and December 2015 were screened for HCV virus replication. Twenty-eight patients who showed active HCV replication were included in the study. All were counseled for the risk of untreated HCV infection and about the cost, duration, response, and adverse effects of DAA therapy. Two patients with estimated glomerular filtration ratio (eGFR) of <30 ml/min/1.73 m2, one patient with hepatic decompensation, and three patients who did not consented for the study were excluded from the study. Thus, 22 patients with replicative HCV virus with an eGFR of ≥30 ml/min/1.73 m2 were treated with DAAs. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before initiation of therapy. The study was approved by the institute's ethics committee.

Direct-acting antiviral agent regimens

Selection of the DAA regimen was based on the availability of the drugs in India and as per the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines for HCV infection in liver transplant recipients.[15] Combination of sofosbuvir with weight-based ribavirin was used initially. Sofosbuvir 400 mg/day was used in all patients. Ribavirin was started with an initial dose of 600 mg daily in divided doses, increased monthly by 200 mg daily to a maximum dose of 1000 mg (<75 kg) to 1200 mg (≥75 kg), if tolerated. During therapy, ribavirin dose was adjusted for hemoglobin level and continued till end of therapy. Fourteen patients completed 24 weeks of treatment with the dual-drug regimen. Subsequently, with change in AASLD/IDSA recommendation[16] and with availability newer DAAs in India, either daclatasvir 60 mg/day (genotype 3, n = 4 and genotype 1, n = 1) or ledipasvir 90 mg/day (genotype 1, n = 3) was used along with sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Triple-drug regimen was used for the duration of 12 weeks.

Baseline and follow-up

Pre and post-transplant characteristics including HCV-related information (i.e., genotype, duration of infection, previous treatment received, and response thereof) were retrieved from hospital records. Baseline laboratory tests including HCV viremia and liver fibrosis were done before treatment. Patients were prospectively followed up with liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase [AST], and gamma-glutamyltransferase [GGT]), renal function tests (serum creatinine and spot protein-to-creatinine ratio), complete hemogram, and calcineurin inhibitor (CNI, tacrolimus or cyclosporine) trough levels. Parameters were assessed before start of treatment (at baseline, w0), during treatment (at 4 weeks, w4), at the end of treatment (at 12 weeks, w12 and 24 weeks, w24), and during post-treatment follow-up (at 36 weeks, w36 and 48 weeks, w48). Viral load was measured by a quantitative HCV RNA assay (lower limit of detection of 15 log IU/mL, Cobas Amplicor HCV, Roche) before treatment (w0), at 4 weeks during the treatment (w4, rapid virological response [RVR]), at the end of therapy (ETR), and at 12 weeks and 24 weeks after completion of therapy (SVR12 and SVR24). Nomenclature used for virological response parameters (i.e., RVR, ETR, SVR12, and SVR24) was according to recent recommendations.[17] Liver fibrosis at baseline was evaluated by elastometry (Fibroscan, Echosens, France) which has been shown to correlate with liver biopsy (i.e., median E value cutoffs of <9.4, 9.5–12.4, and >12.5 kPa corresponding to METAVIR scores of F0-F2, F3, and F4, respectively).[18] Liver biopsy was not performed in any of the patients.

Immunosuppressive regimen, CNI level and their dose adjustments, and evaluation and management of any graft dysfunction were done as per department protocol and were not influenced by the study. During the entire study period of 48 weeks (i.e., 24 weeks of therapy and 24 weeks of follow-up after therapy), note was made of changes in CNI dose, requirement of iron or erythropoietin supplementation, and other significant clinical events.

Statistical analyses

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation with range and in number as per requirement to express the data. Continuous variables were compared using paired Student's t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test and categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square or Fisher's exact test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows, Version 16.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc and GraphPad prism 5.0. Graphpad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA.

Results

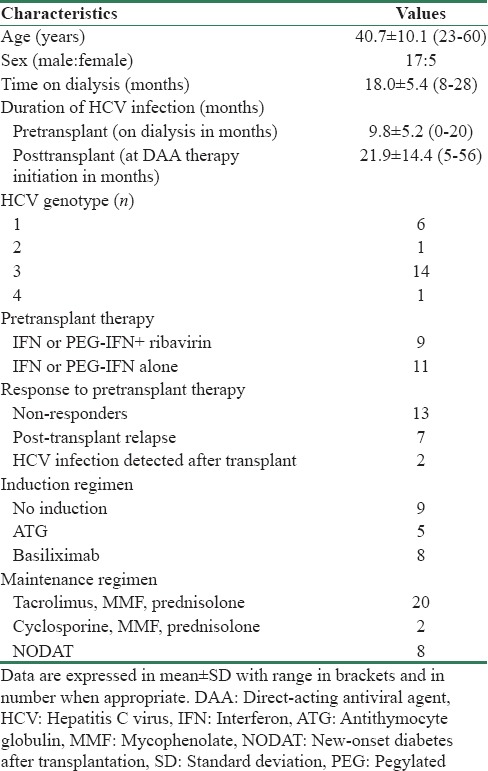

Pretreatment patient characteristics and baseline laboratory values are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Majority of the patients had genotype 3 infection (n = 14/22, 64%). Thirteen patients (n = 13/20, 65%) were IFN nonresponder and seven (n = 7/20, 35%) had relapse of HCV replication after transplantation. In two patients, viremia was detected in posttransplant period when evaluated for raised liver enzymes.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients

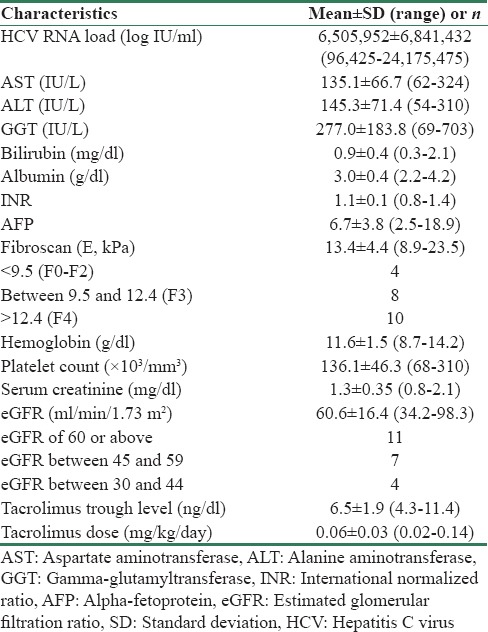

Table 2.

Baseline (week 0) laboratory values of patients

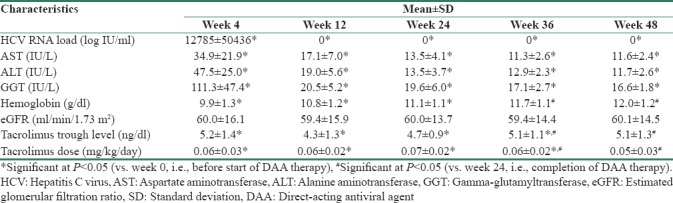

Laboratory parameters during and after therapy are compared with corresponding baseline values in Table 3. At start of therapy, HCV RNA copies were 6505952 ± 6841432 (96425–24175475) logs IU/mL. Twenty patients had undetectable viremia after 4 weeks of therapy (n = 20/22, RVR = 91%). Two patients, both of genotype 1, had persistent viremia at 4 weeks but had significant decline from baseline (from 4345672 to 47207 logs IU/mL and from 24175475 to 23407 logs IU/mL, respectively). All 22 patients had undetectable viremia at end of therapy (ETR = 100%) and during follow-up at 12 and 24 weeks after completion of therapy (both SVR12 and SVR24 = 100%). Changes in the liver enzyme levels are shown in Figure 1. Serum AST, ALT, and GGT levels showed significant decrease during treatment. All the three enzyme levels had normalized by end of therapy and remained similar during the follow-up period.

Table 3.

Clinical parameters of patients during and after treatment

Figure 1.

Liver enzyme levels before, during, and after therapy. *Significant (P < 0.05) in comparison to corresponding baseline (w0) values

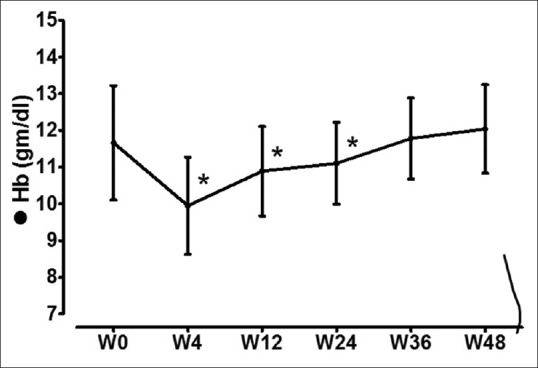

Compared to baseline, there was a significant fall in hemoglobin levels [Figure 2] at 4 weeks (w4 vs. w0, P = 0.000) and at 12 weeks of therapy (w12 vs. w0, P = 0.037); however, levels became similar at end of treatment (w24 vs. w0, P = 0.112) and on follow-up (w36 vs. w0, P = 0.692 and w48 vs. w0, P = 0.249). Initial ribavirin dose of 600 mg was reduced to 400 mg in five patients and to 200 mg in one patient due to progressive anemia. Four out of these 6 patients had impaired kidney function at baseline (eGFR of 34.2, 37.2, 42.5, and 42.6 ml/min/1.73 m2). Three patients required oral iron and erythropoietin supplementation. One patient with hemoglobin of <7 mg/dl had received one unit of packed red blood cell transfusion. All patients completed therapy with ribavirin. There was no significant change in platelet count during the entire study period.

Figure 2.

Hemoglobin levels before, during, and after therapy. *Significant (P < 0.05) in comparison to corresponding baseline (w0) values

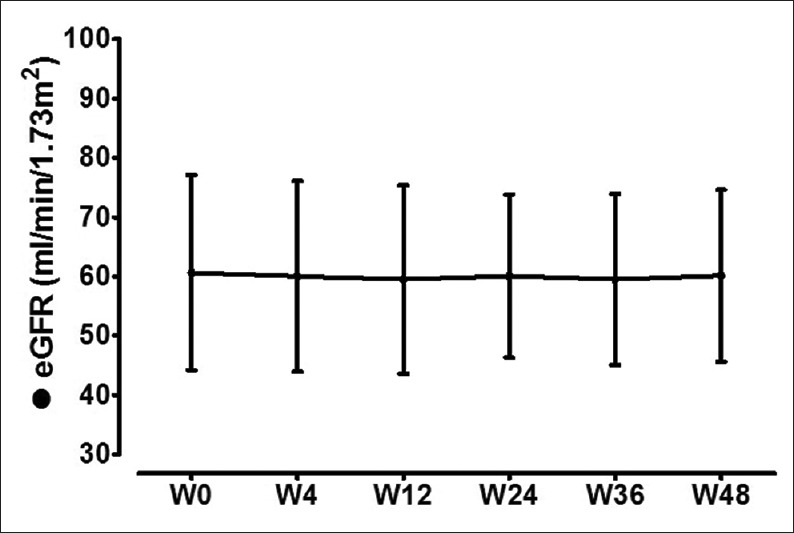

As compared to baseline values, there was no significant changes in eGFR [Figure 3] during or after completion of therapy. There was no significant change in spot urinary protein-to-creatinine ratios from baseline values to end of therapy and last follow-up. There was no episode of acute rejection or any graft loss during the study period.

Figure 3.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate levels before, during, and after therapy. *Significant (P < 0.05) in comparison to corresponding baseline (w0) values

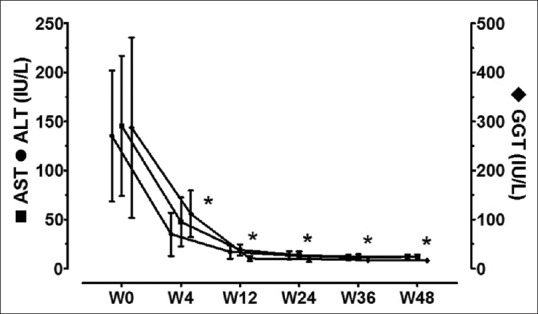

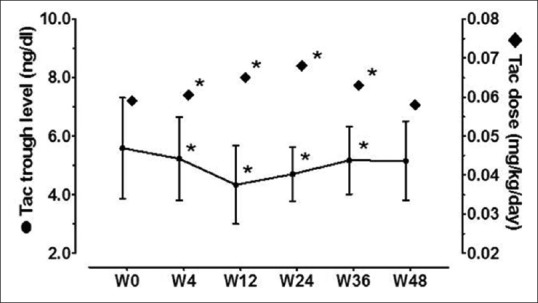

All patients were on triple immunosuppression including a CNI (tacrolimus, n = 20 or cyclosporine, n = 2). There was a significant decrease in tacrolimus trough level [Figure 4] during treatment, at the end of treatment, and during the follow-up period. Compared to baseline, tacrolimus dose was higher during treatment, at the end of therapy, but was similar at end of follow-up. Twelve patients required tacrolimus dose adjustment during DAA therapy (increased, n = 10/12, 83% and decreased, n = 2/12, 17%) and 8 patients required dose adjustment during follow-up (increased, n = 5/8, 62% and decreased, n = 3/8, 38%). There was no alteration in cyclosporine level or dose. Doses of mycophenolate and prednisolone were not changed during the study.

Figure 4.

Tacrolimus trough levels and tacrolimus doses before, during, and after therapy. *Significant (P < 0.05) comparisons with corresponding baseline (w0) values

Eight patients had new-onset diabetes after transplantation (NODAT); six patients were on insulin therapy and one patient was on oral hypoglycemic agent. There was neither a significant change in fasting glucose levels nor requirement of total insulin dose during or after treatment.

Discussion

In the present study, we observed RVR and SVR with the therapy without any breakthrough HCV replication during the study period. Treatment was associated with rapid decline in both hepatocellular and biliary duct injury as evidenced by rapid normalization serum levels of AST, ALT, and GGT during initial 4 to 12 weeks. Our results were similar to those recently published studies with the use of DDAs in renal allograft recipients with RVR of 70%–88%, ETR of 100%, and SVR12 of 100%.[13,14] Similar to them, we have also observed that tolerance to the therapy was excellent without significant adverse effects that can be attributed to sofosbuvir, daclatasvir, or ledipasvir. The fall in hemoglobin level (mean decrease of 0.8 mg/dl) in ribavirin-based therapy was expected; however, it was well tolerated. Ribavirin exerts concentration-dependent toxicity through oxidative membrane damage leading to extravascular hemolysis and fall in hemoglobin.[19] Ribavirin dose was reduced because of progressive anemia in three patients; other patients were managed with iron and erythropoietin supplementation. Only one of the patients required blood transfusion. Of note, all the three patients who developed anemia after ribavirin had preexisting allograft dysfunction (i.e., eGFR of 30–44 ml/min/1.73 m2). However, no patient discontinued ribavirin before completion of therapy. Incremental dosing protocol with a weight-based maximum dose of ribavirin and use of erythropoietin can minimize this problem.[20] There was no significant change in renal function or degree of proteinuria during the study. No episode of acute rejection or graft loss occurred.

Although HCV-infected renal transplant recipients had poorer patient and graft survival rates than non-infected ones, still renal transplantation offers significant survival advantage as compared to those who remain on dialysis, thus is considered as the treatment of choice.[3,4] As compared to non-infected renal allograft recipients, these patients carry increased risk of NODAT, secondary infections, and acute liver failure.[1,2] Excess mortality is due to higher incidence of cardiovascular disease, sepsis, chronic liver disease, and malignancy.[3] Lower allograft survival has been attributed to higher rate of rejections, transplant glomerulopathy, and de novo post-transplant glomerular disease.[21] The treatment of HCV infection has been associated with decrease in the incidence of these complications.[22] However, IFN-based therapy is relatively contraindicated in renal allograft recipients because of high incidence of acute rejections.[5,9] The accumulating data on safety and efficacy of DDAs will boost confidence of using these agents in the treatment of HCV infection in post-transplant period.[23]

A trend of decrease in tacrolimus trough levels was observed during therapy and increase in dose of tacrolimus was required to maintain the recommended drug level for that period. Similar observations have been reported from previous studies.[12,14] Patients with chronic liver disease usually require lesser dose of CNIs to maintain similar trough levels as compared to those without.[24] The mechanism of increased calcineurin level in HCV-infected patients and its decline after clearance of viremia is currently unknown and may be related to alteration of hepatic metabolism of the drug and improvement in hepatic function.[24,25] Hence, frequent drug-level monitoring and careful dose adjustment are required during and after therapy to prevent acute rejection due to lower drug levels. However, we have not studied the changes in the area under curve of the tacrolimus with the therapy in these patients.

Limitations and strength of the study

The study is limited by small number of patients and use of different DAA regimens for treatment. The strength of the study is a prospective observational study with close follow-up in clinical practice setting and patients were followed up to 1 year.

Conclusion

Sofosbuvir-based therapy is highly effective and well tolerated without any adverse impact on renal function in HCV-infected renal allograft recipients. Although initial results are promising, the long-term outcomes including breakthrough HCV replication and effect on progression of chronic liver disease are yet to be seen.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Morales JM, Fabrizi F. Hepatitis C and its impact on renal transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:172–82. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbone M, Mutimer D, Neuberger J. Hepatitis C virus and nonliver solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95:779–86. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318273fec4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabrizi F, Martin P, Dixit V, Messa P. Meta-analysis of observational studies: Hepatitis C and survival after renal transplant. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21:314–24. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingsathit A, Kamanamool N, Thakkinstian A, Sumethkul V. Survival advantage of kidney transplantation over dialysis in patients with hepatitis C: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2013;95:943–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182848de2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hepatitis C in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;73:S53–68. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AASLD-IDSA. [Last accessed on 2016 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.hcvguidelines.org/ full-report/unique-patient-populations-patients-renal-impairment .

- 7.Fabrizi F, Dixit V, Messa P, Martin P. Antiviral therapy (pegylated interferon and ribavirin) of hepatitis C in dialysis patients: Meta-analysis of clinical studies. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21:681–9. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth D, Bloom R. Selection and management of hepatitis C virus-infected patients for the kidney transplant waiting list. Contrib Nephrol. 2012;176:66–76. doi: 10.1159/000333774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabrizi F, Penatti A, Messa P, Martin P. Treatment of hepatitis C after kidney transplant: A pooled analysis of observational studies. J Med Virol. 2014;86:933–40. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwo PY, Mantry PS, Coakley E, Te HS, Vargas HE, Brown R., Jr An interferon-free antiviral regimen for HCV after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2375–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlton M, Gane E, Manns MP, Brown RS, Jr, Curry MP, Kwo PY. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for treatment of compensated recurrent hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:108–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutierrez JA, Carrion AF, Avalos D, O’Brien C, Martin P, Bhamidimarri KR, et al. Sofosbuvir and simeprevir for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:823–30. doi: 10.1002/lt.24126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamar N, Marion O, Rostaing L, Cointault O, Ribes D, Lavayssière L, et al. Efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir-based antiviral therapy to treat hepatitis C virus infection after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1474–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawinski D, Kaur N, Ajeti A, Trofe-Clark J, Lim M, Bleicher M, et al. Successful treatment of hepatitis C in renal transplant recipients with direct-acting antiviral agents. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1588–95. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.hcvguidelines.org/full-report/unique-patient-populations-patients-who-develop-recurrent-hcvinfection- post-liver .

- 16. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 10]. Available from: http://www.hcvguidelines.org/full-report/unique-patient-populations-patients-who-develop-recurrent-hcvinfection- post-liver .

- 17.Wedemeyer H, Jensen DM, Godofsky E, Mani N, Pawlotsky JM, Miller V, et al. Recommendations for standardized nomenclature and definitions of viral response in trials of hepatitis C virus investigational agents. Hepatology. 2012;56:2398–403. doi: 10.1002/hep.25888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganne-Carrié N, Ziol M, de Ledinghen V, Douvin C, Marcellin P, Castera L, et al. Accuracy of liver stiffness measurement for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with chronic liver diseases. Hepatology. 2006;44:1511–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Franceschi L, Fattovich G, Turrini F, Ayi K, Brugnara C, Manzato F, et al. Hemolytic anemia induced by ribavirin therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: Role of membrane oxidative damage. Hepatology. 2000;31:997–1004. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gergely AE, Lafarge P, Fouchard-Hubert I, Lunel-Fabiani F. Treatment of ribavirin/interferon-induced anemia with erythropoietin in patients with hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;35:1281–2. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rostami Z, Nourbala MH, Alavian SM, Bieraghdar F, Jahani Y, Einollahi B, et al. The impact of hepatitis C virus infection on kidney transplantation outcomes: A systematic review of 18 observational studies: The impact of HCV on renal transplantation. Hepat Mon. 2011;11:247–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lens S, Gambato M, Londoño MC, Forns X. Interferon-free regimens in the liver-transplant setting. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:58–71. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1371011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saxena V, Terrault NA. Treatment of hepatitis C infection in renal transplant recipients: The long wait is over. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1345–7. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwo PY, Badshah MB. New hepatitis C virus therapies: Drug classes and metabolism, drug interactions relevant in the transplant settings, drug options in decompensated cirrhosis, and drug options in end-stage renal disease. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2015;20:235–41. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolffenbüttel L, Poli DD, Manfro RC, Gonçalves LF. Cyclosporine pharmacokinetics in anti-HCV+patients. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:654–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]