Abstract

Recovery housing is a service delivery modality that simultaneously addresses the social support and housing needs of those in recovery from substance use disorders. This paper describes a group of recovery homes in Texas (N=10) representing a lesser-studied type of recovery housing, one which explicitly bridges treatment and peer support by providing a variety of recovery support services. All residents meet with a recovery coach, undergo regular drug screening, and have access to intensive outpatient treatment—a program that was developed specifically to support the needs of residents in the homes. Unlike the Oxford HouseTM model and California sober living houses, which are primarily financed through resident fees, these homes are supported through a mix of resident fees as well as private and public insurance. While adhering to some aspects of the social model of recovery, none of these homes would meet criteria to be considered a true social model program, largely because residents have a limited role in the governance of the homes. Residences like the ones in this study are not well represented in the literature and more research is needed.

Keywords: addiction, recovery, recovery housing, recovery support services, recovery residences, sober living

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are a pervasive problem in the US. Approximately 21.5 million people aged 12 or older in 2014 had an SUD in the past year, including 17.0 million people with an alcohol use disorder, 7.1 million with an illicit drug use disorder, and 2.6 million who had both an alcohol use and an illicit drug use disorder (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2015). Although the percentage of people aged 12 or older who had past year SUDs in 2014 was similar to the percentages from 2011 to 2013, and lower than the percentages from 2002 to 2010, deaths from drug overdoses are at an all-time high due an “unprecedented opioid epidemic” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2016). Since 2000, the rate of deaths from drug overdoses has increased 137%, including a 200% increase in the rate of overdose deaths involving opioids--opioid pain relievers and heroin (Rudd et al. 2016).

Despite the devastating personal and societal costs of addiction and the development and demonstrated effectiveness of substance use treatments (National Institute on Drug Abuse 2012; Pearson et al. 2012), few people who need treatment receive it (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] 2014). And while addiction is increasingly recognized as a chronic condition necessitating lifestyle change and ongoing care (Dennis & Scott 2007; McLellan et al. 2000), most substance use treatment is time-limited and may not include the type of services clients prioritize as being critical to their recovery (Duffy & Baldwin 2013; Laudet, Stanick & Sands 2009; Laudet & White 2010). Safe and stable housing has been identified by SAMHSA (2012) as integral to recovery, but studies have found that nearly a third (32%) of individuals entering substance use treatment report being marginally housed in the 30 days prior to treatment entry (Eyrich-Garg et al. 2008).

Recovery housing is a promising service delivery mechanism to ensure that individuals in recovery have an alcohol-/drug-free and supportive living environment that promotes health, wellness, and purpose (SAMHSA, 2012) and fosters a lifestyle characterized by sobriety, personal health, and citizenship (The Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel 2007). It is commonly used after inpatient or residential treatment (Reif et al. 2014) but could also be used during or after outpatient treatment or as an alternative to treatment (Polcin 2006; Polcin & Henderson 2008). Recovery residences (the physical structures in which people reside) go by a variety of different names (e.g., Oxford Houses, sober living houses, sober homes, recovery homes), but they generally refer to sober, safe, and healthy living environments that promote recovery from alcohol and drug use and associated problems (Jason et al. 2013).

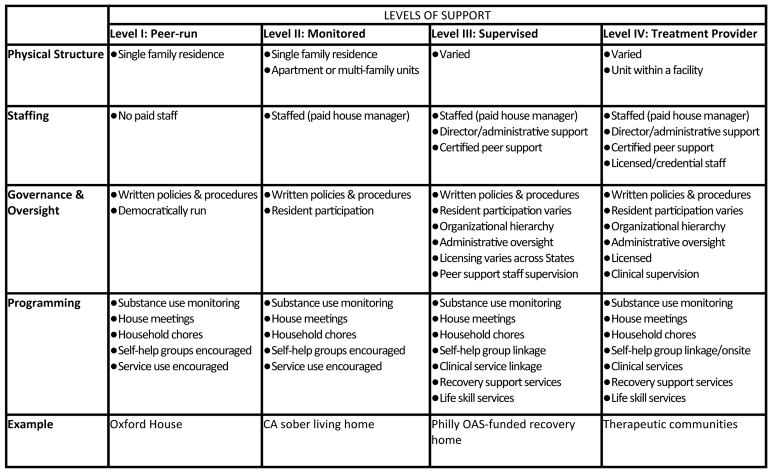

Recognizing that a variety of different types of residences could meet this definition, the National Alliance for Recovery Residences (NARR) developed categories for levels of care provided by different types of residences as well as standards of practice for each (NARR, 2012). As Figure 1 depicts, recovery residences can run the gamut from being completely peer-run (i.e., having no staff) and providing no formal treatment or services, such as with the Oxford House model, to models that would be characterized as substance use treatment except that it actively involves residents in the treatment process, such as in therapeutic communities (TCs; De Leon 2000). Other dimensions in which houses differ may be reflected in the physical setting (e.g., peer-run residences are operated in single-family homes while treatment providers like TCs may be operated in a variety of settings including a unit in a larger residential facility) and in governance and oversight (e.g., peer-run residences are democratically run and are not licensed treatment providers, while at the other end of the spectrum, treatment providers must be licensed and resident participation in governance may vary). Yet regardless of the amount and nature of services provided, central to recovery residences across the spectrum of NARR levels are ideas of inherently valuing peer support and mutual aid, experiential knowledge, and residents’ active participation in their recovery and in the functioning of the house. These principles are hallmarks of “social model” recovery programs (Borkman et al. 1998; Room, Kaskutas & Piroth 1998).

Figure 1.

Recovery Residence Characteristics by NARR Level

Studies of residents in Oxford Houses, sober living houses in California, and TCs have found that these types of environments are associated with a variety of positive outcomes including abstinence from alcohol and drugs, gains in employment, and decreased involvement in the criminal justice system (De Leon 2010; Jason et al. 2006; Jason et al. 2007; Polcin et al. 2010; Polcin et al. 2010; Vanderplasschen et al. 2013). Despite these positive findings, important gaps in the scientific literature on recovery housing exist because research has focused on recovery housing that is generally considered substance use treatment (TCs) and recovery housing that only provides peer support (Oxford Houses and sober living houses in California). Some research conducted on recovery homes in Philadelphia has described recovery residences that are purposefully linked with substance use treatment and that also provide residents with a variety of services in addition to social support and mutual aid as part of their stay in the residence (Mericle, Miles & Cacciola 2015; Mericle et al. 2014), but other descriptions of this model of recovery housing are lacking.

Further, although there has been research on the characteristics of neighborhoods in which Oxford Houses (Ferrari, Groh & Jason 2009) and sober living houses in California are located (Mericle et al. 2016), we also know little about the neighborhoods in which residences that blend peer support and professional recovery support services are located—another important gap in the literature given growing evidence of the role that neighborhood factors play in increasing risk for substance use (Jacobson 2004; Mennis & Mason 2012; Molina, Alegría & Chen 2012). To address these gaps in the literature, the aim of this paper is to examine the residence, neighborhood, procedural, and recovery orientation characteristics of a group of recovery residences in Texas (N=10) that exemplify a model that explicitly bridges treatment and peer support with recovery support services for residents.

Methods

Data for this study were collected from structured interviews with house managers (N=11) in the fall of 2015. The study protocol and procedures were approved and monitored by the Public Health Institute’s Institutional Review Board.

Sites and Participants

The group of residences studied are run by Eudaimonia Recovery Homes which was founded in November of 2009 in Austin, Texas. Eudaimonia also has homes in Houston and Boulder, Colorado. In Austin at the time of the study, there were Eudaimonia homes for adult (age 18 or older) women (n=3), men (n=6), and one home specifically designated for gay/bisexual men (n=1), representing a total capacity of 117 beds. In the Eudaimonia model, sober living is conceptualized as a structured and accountable environment for individuals to continue in their recovery journey (potential residents must have at least 30 days sober). Admissions and intake are centralized. Eudaimonia accepts a range of potential residents, however, in addition to age and sobriety criteria, residents must be medically managed if they have been diagnosed with a psychotic disorder. Although there is no upper limit to the age of residents accepted, the majority of residents are under 30. There is also no upper limit on how long residents can stay in the homes. Residents are encouraged to stay in the homes for at least six months, however the average length of stay is generally closer to 90 days.

While all Eudaimonia homes are inspected and certified by the Texas Recovery-Oriented Housing Network (TROHN) which is affiliated with NARR, these homes are not licensed residential treatment programs. However, unlike other types of recovery residences, such as Oxford Houses and sober living houses in California, all residents in Eudaimonia homes receive recovery support services provided to residents at the Eudaimonia office. These services include drug/alcohol testing, drug/alcohol education groups, and weekly individual meetings with a professional recovery coach who provides residents with peer support1 and life skills mentoring as well as case management services. To better address the needs of their residents, Eudaimonia opened an intensive outpatient treatment program through Nova Recovery Center. This program offers relapse prevention and other group counseling, relaxation and stress management, and employs a part-time life coach to provide job readiness counseling and a part-time psychiatrist. Residents are not required to participate in substance use treatment at Nova or any other treatment program during their stay, but they are required to attend AA/12-step meetings. Costs associated with running the Austin Eudaimonia homes are primarily covered though residents’ self-pay (50%), but some costs are covered through private and state-sponsored insurance (35%). An estimated 15% of costs are either written off or considered donated (e.g., residents given scholarships or services provided pro bono).

Each Eudaimonia recovery home has an identified house manager who is compensated with a monthly stipend for overseeing the day-to-day activities in the home. A total of 11 house managers were interviewed for this study, reporting on 10 different homes (note—one home is a duplex with one house manager, and another is actually two homes right next door to each other under the supervision of one house manager). Two house managers reported on the same home. This occurred because, at the time the majority of interviews were conducted, one of the house managers was just recently (that week) hired. Fortunately, the former house manager for that home was still employed at Eudaimonia and was interviewed about it. On a subsequent visit (approximately 2 months later), the current house manager was interviewed. Reports from both house managers were largely identical. However, when responses were discrepant, information about current operations and house/neighborhood characteristics were taken from the current house manager’s interview and information about program policies (that the current manager might not know) or answers to questions that required a longer perspective were taken from the former house manager’s interview. All managers were in recovery themselves, and the majority were male (64%), White/Caucasian (91%), and under 30 years of age (64%), had a high school degree (73%), and were a house manager for fewer than three years (82%). While many held some sort of trade or professional certification, only one house manager held a certification related to the addictions field.

Recruitment and Data Collection Procedures

The Eudaimonia Director of Operations scheduled a time for each of the house managers to meet with study staff about potential participation in an interview about their home. House managers were eligible to participate in the study if they were 18 years of age or older and had been in the position of house manager for at least two weeks. The purpose as well as the voluntary and confidential nature of participation in the study was explained to the house managers by study staff (AAM). To further protect house managers from the risk of perceived coercion to participate in the study, a Letter Agreement between study staff and Eudaimonia was developed specifying that Eudaimonia would not pressure house managers to participate in the study and that manager’s decision to participate or not to participate in the study would not affect their employment at Eudaimonia Recovery Homes. All house managers provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Meetings with the house managers were scheduled at their convenience and took place at their recovery home, in the Eudaimonia offices, or at another easily accessible location in a quiet and semi-private space (i.e., a cafe). Completion of the structured interview took place with study staff (AAM) immediately after consent to participate was obtained and lasted 45–60 minutes. Data were collected in a paper and pencil format, with the interviewer reading the questions and the response options aloud to the house managers, and later entered into a database for analyses. House managers received $25 for participating in the study. When interviews took place at or near the home, study staff was able to observe the interior and exterior condition as well as the layout of the residence.

Measures & Statistical Analyses

We developed the instrumentation for the house manager interview from available measures used to study other types of recovery residences (e.g., Oxford Houses, California sober living houses, and recovery homes in Philadelphia). Information pertaining to residence (e.g., physical characteristics of the home, resident capacity, and amenities/features) and neighborhood characteristics as well as residence policies and procedures was gathered with items from the Oxford House Environmental Audit and House Processes Questionnaire developed by researchers at DePaul University (Ferrari, Groh & Jason 2009; Ferrari et al. 2006; Ferrari et al. 2004; Ferrari et al. 2006). One of the items in this instrument asks respondents to characterize the neighborhood in which the residence is located by asking them to respond “yes” or “no” to 13 statements about the surrounding neighborhood. From these items, we created various indicators of neighborhood risk to identify obvious signs of neglect (e.g., litter, empty buildings, run-down buildings, lack of trees/greenery), signs of disadvantage (e.g., area seems economically depressed, homeless persons on the streets, pawn shops), signs of being unsafe (e.g., deserted during the day/night, streets not lit at night), and substance use triggers (e.g., intoxicated/drugged people on the streets, obvious signs of drug dealing).

We also included the Social Model Philosophy Scale (SMPS; Kaskutas et al. 1998), which was designed to measure the extent to which substance use programs adhere to a social model approach across six program domains: physical environment, staff role, authority base, view of dealing with substance use problems, governance, and community orientation. Items in the physical environment domain (n=6) assess the residence’s proximity to a clinical setting and the aspects of the residence that diminish staff/resident hierarchy, facilitate peer support, and increase resident responsibility for the residence and those within it. Items in the staff role domain (n=5) assess the nature of the staff relationship with residents. Items in the authority base domain (n=5) assess the residence’s commitment to experiential knowledge. Seven items are used to assess how the residence views how to deal with substance use problems and the resident’s role in his/her recovery. Items in the governance domain (n=4) assesses the extent to which residents are involved in the creation and enforcement of house rules. The six community orientation items assess the extent to which the residence facilitates residents making and keeping relationships with persons in recovery and engagement in the community.

The 33-item SMPS has been shown to have high internal reliability (α= 0.92) with subscale alphas ranging from 0.57–0.79. Test-retest analyses have shown high consistency across time, administrators, and respondents. Items in this measure were summed according to criteria outlined in the scoring manual (Room & Kaskutas 2008). Scores on the overall scale and the subscales can range from 0–100, with higher scores indicating greater adherence to the social model philosophy. We used the established cut-point of 75 to determine whether homes operated as social model programs (Kaskutas et al. 1998; Kaskutas, Keller & Witbrodt 1999).

This study implemented descriptive statistical techniques. Frequencies were run to summarize the physical, neighborhood, and governance (e.g., policy and procedural) characteristics of the homes studied. We averaged total and subscale scores for each domain of the SMPS and also calculated the percent of homes that would be considered adherent to the social model based on their scores. All analyses were conducted in Stata version 14 (Stata Corp. 2015).

Results

Table 1 presents information collected from the house managers about the physical characteristics of the residences and the characteristics of the neighborhoods in which they were located. In terms of the size of the residences, house size ranged from 8 to 19 beds and the majority (80%) had a capacity to house more than ten residents. House managers had their own rooms in each of the homes and residents generally shared a room with at least one other resident. All but two homes had at least one room that was designated as a “triple” to be shared by three residents. At the time the study was conducted, only two of the ten homes were full, meaning that the majority had at least one vacancy. One home had a private bathroom attached to one of the rooms, but more often than not bathrooms were shared among residents in the home. All homes had a variety of common areas in which residents could socialize (TV/living room, kitchen/dining area, patio and/or open yard areas). All homes were non-smoking and had air conditioning, cable, a washer/dryer, and parking for residents. House managers also noted other amenities such as free WiFi, a dishwasher, garage/storage space, cleaning supplies, coffee, TVs in each room. Fewer than half of the homes (40%) were handicap/wheelchair accessible.

Table 1.

Residence & Neighborhood Characteristics

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| House Characteristics | ||

| Resident capacity | ||

| 10 or less | 2 | 20 |

| 11–151 | 7 | 70 |

| 16–20 | 1 | 10 |

| Houses with triples (e.g., 3 people sharing a room) | 8 | 80 |

| Full houses | 2 | 20 |

| Features/Amenities | ||

| Private bathrooms | 1 | 10 |

| TV/living room | 10 | 100 |

| Kitchen/dining room | 10 | 100 |

| Non-smoking | 10 | 100 |

| Patio/Open yard area | 10 | 100 |

| Air conditioning | 10 | 100 |

| Cable TV | 10 | 100 |

| Washer/dryer | 10 | 100 |

| Parking | 10 | 100 |

| Other2 | 8 | 80 |

| Handicap/wheel chair accessible | 4 | 40 |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | ||

| Neighborhood Type | ||

| Urban | 3 | 30 |

| Inner-city | 3 | 30 |

| Suburban | 4 | 40 |

| Racial/Ethnic Groups Represented (N=9)3 | ||

| Caucasian/White | 9 | 100 |

| African American | 6 | 67 |

| Hispanic | 7 | 78 |

| Other | 3 | 33 |

| Social Class | ||

| Middle class | 4 | 40 |

| Working class | 3 | 30 |

| Mixed | 3 | 30 |

| Resources (Two-block radius) | ||

| Medical services (hospital/clinic) | 3 | 30 |

| Social services (welfare agency, shelter, food pantry) | 1 | 10 |

| Commerce (super market, mall/shopping center, strip mall, gas station) | 7 | 70 |

| Police station | 2 | 20 |

| Library | 4 | 20 |

| Accessible by public transportation | 10 | 100 |

| Other4 | 5 | 50 |

| Signs of neglect (litter, empty buildings, run-down buildings, lack of trees/greenery ) | 2 | 20 |

| Signs of disadvantage (economically depressed, homeless persons on the streets, pawn shops) | 3 | 30 |

| Signs of being unsafe (deserted during the day/night, streets not lit) | 3 | 30 |

| Substance use triggers (intoxicated people on the streets, obvious signs of drug dealing) | 1 | 10 |

Two of these residences were comprised of two different physical structures (a duplex and two houses next door to each other) that were operated as one entity.

Other amenities mentioned included free Wi-Fi, dishwasher, garage/storage space, cleaning supplies, coffee, TVs in each room.

One respondent responded DK to all racial/ethnic neighborhood composition items.

Other resources/amenities mentioned included churches, an AA club house, a community garden, gyms/fitness centers, vet clinics, restaurants, and a barber shop.

In terms of their perceptions about neighborhoods in which the homes were located, most house managers identified their neighborhoods as urban or inner-city (60%). With respect to the racial and ethnic composition of the neighborhoods, Caucasians/Whites were present in all neighborhoods, but the majority of house managers also noted that other racial/ethnic groups were represented in the neighborhood. Most house managers reported that their neighborhood was working or middle class (70%). All homes were accessible by public transportation and the majority of house managers reported places of commerce (e.g., super markets, shopping centers, gas stations) within a two-block radius of the home (70%). Other neighborhood resources (e.g., medical services, social services, a police station, or a library) were less uniformly present within a two-block radius of the homes, but 60% of the houses had at least three different types of neighborhood resources. Some homes were also in a two-block radius of other types of resources such as churches, an AA club house, a community garden, gyms/fitness centers, restaurants, and a barber shop. The majority of the homes were in neighborhoods that did not show obvious signs of being neglected, disadvantaged, unsafe, or where there was obvious signs of substance use or drug dealing. In fact, managers of only two homes reported more than one type of neighborhood risk factor.

Table 2 lists information provided by house managers about their home’s policies and procedures. Half of the house managers identified their residence as a sober living house, but others identified theirs as an Oxford House or a recovery home, and one manager identified their residence as something in between a TC and a recovery home. Managers of all homes reported that their home was very much based on 12-step principles. In terms of the primary substance use issue of residents in their homes, house managers reported that the majority of residents in 80% of the homes where in recovery from addiction to both alcohol and drugs. The majority of residences ensured that residents received an orientation to the home upon entry (80%) as well as a resident handbook (60%) and that house rules were clearly posted. None of the homes served family-style meals (or provided residents with food for meals), but residents participated in household chores in all of the homes—the majority (90%) having the house manager assign the chores to the residents. All homes had weekly house meetings as well as rules and policies for residents regarding house meeting attendance, curfew, spending the night outside of the home as well as prohibitions against overnight guests in the home and substance use on or off the premises. Managers at each of the homes indicated that the consequence of not following rules regarding substance use was immediate eviction from the home, but some managers noted that attempts were also made to connect these residents with resources and one noted that the home sometimes let residents stay in the home overnight and leave in the morning.

Table 2.

Residence Policies and Procedures

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| House Type | ||

| Sober living house | 5 | 50 |

| Oxford House | 1 | 10 |

| Recovery home | 3 | 30 |

| Something else1 | 1 | 10 |

| 12-Step Orientation | ||

| Not at all | 0 | 0 |

| A little | 0 | 0 |

| Somewhat | 0 | 0 |

| Quite a bit | 0 | 0 |

| Very much | 10 | 100 |

| Primary SUD Issue | ||

| Drugs | 2 | 20 |

| Drugs and alcohol | 8 | 80 |

| Alcohol | 0 | 0 |

| Procedures | ||

| Residents handbook | 6 | 60 |

| Resident orientation | 8 | 80 |

| House rules posted | 6 | 60 |

| Weekly house meetings | 10 | 100 |

| Family-style meals | 0 | 0 |

| Assigned chores | 9 | 9 |

| Policies | ||

| Sanctions for arriving late or leaving house meetings early | 10 | 10 |

| Curfew | 10 | 10 |

| Rules for overnights | 10 | 10 |

| Rules for guests in rooms | 10 | 10 |

| Consequences for substance use | ||

| Eviction | 10 | 10 |

| Other1 | 4 | 4 |

One respondents said that the house was something in between a recovery home and a therapeutic community.

Three respondents noted that they also try to refer the resident to treatment or other services; one mentioned allowing the resident to stay overnight and leave in the morning.

Table 3 lists the overall as well as domain-specific scores assessed with the Social Model Philosophy Scale. Scores (which can range from 0–100) were highest in the domains of authority base (M=93.0, SD=7.9), physical environment (M=79.0, SD=5.2), and community orientation (M=77.5, SD=6.6). Scores were lowest in the domain of governance (M=3.8, SD=8.4). The average overall score across domains was 62.7 (SD=4.4). None of the programs had an overall score over 75, which was considered the cut-off for true social model programs when the instrument was developed. However, all had scores over 50, scores indicative of “hybrid” programs in which social model principles dominate (Kaskutas et al. 1998).

Table 3.

Adherence to Social Model Philosophy

| M | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Environment (6 Items) | 79.0 | 5.2 |

| Staff Role (5 items) | 65.0 | 12.2 |

| Authority Base (5 Items) | 93.0 | 7.9 |

| View of Dealing with Alcohol/Drug Problems (7 Items) | 70.0 | 7.4 |

| Governance (4 Items) | 3.8 | 8.4 |

| Community Orientation (6 Items) | 77.5 | 6.6 |

| Overall Score (33 Items) | 62.7 | 4.4 |

Notes: Each item can be assigned a value from 0–1. Scores range from 0–100 and represent the average score (total score for items/number of items) multiplied by 100.

Discussion

This study describes a group of recovery homes in Texas that share many characteristics of Oxford Houses and sober living houses studied in California. The residences are set up in a home-like fashion and located in largely working and middle-class residential neighborhoods. The homes have rules regarding substance use both on and off the premises and residents are expected to participate in household chores and to attend weekly house meetings. However, unlike Oxford Houses, these residences are staffed by a house manager, and unlike either Oxford Houses or sober living houses in California, residents living in these homes are provided recovery support services delivered by professional recovery coaches, have access to additional substance use treatment services via linkage to an intensive outpatient treatment program opened specifically to meet the needs of the recovery home residents, and can use insurance to cover costs of services provided. Although it is not uncommon for individuals living in Oxford Houses and sober living houses in California to be receiving treatment and potentially recovery support services while they are living there, these residences do not provide such services directly to residents. The homes in this study are also different from therapeutic communities. Although the homes in this study are staffed and residents receive recovery support services, the house managers of these homes were not degreed or licensed addictions counselors and the homes are not licensed as short- or long-term residential treatment. Given the unique set of features, it is not surprising that house managers struggled with how to classify their homes.

There currently exists no comprehensive listing of recovery residences and no systematic surveillance of them (Polcin et al. 2016) to determine the prevalence of recovery housing or to monitor changes in this component of the substance use continuum of care. However, there is evidence to suggest that recovery housing is more prevalent and that it is evolving (Mericle, Miles & Cacciola 2015; Mericle et al. 2014). Efforts to define recovery and principles of care to promote recovery have set the stage to expand the scope of substance use treatment services as they have been traditionally been conceptualized and delivered. It is now not uncommon to see treatment programs that have opened recovery residences as part of their aftercare services and to support those who are currently in outpatient care (Polcin et al. 2010) or to see treatment programs partnering with recovery residences, an arrangement that is often referred to as the “Florida model” (Mericle et al. 2014). Growing acceptance of recovery has also helped set the stage to raise awareness about recovery among young people and in non-traditional settings, such as in recovery high schools and in collegiate recovery communities (Laudet & Humphreys 2013).

The recent opioid epidemic presents a variety of challenges to those providing recovery support services who are having to contend with addiction that is generally more medically complex, increasingly treated with medication, and where relapse can be deadly. Heroin use has increased among all age groups but use has increased the most among those 18–25 (Jones et al. 2015), ushering in an increasingly younger and clinically complex cohort of individuals who need recovery support services. Stories about deaths from drug overdoses among residents appearing in the press and growth in demand for recovery housing have sparked calls for increased professionalization and regulation of recovery housing (Johnson 2016). Given these forces on the treatment system and on the recovery support system to meet the evolving needs of those with substance use disorders, it is not surprising to see mixing of treatment and recovery housing elements--treatment programs offering recovery housing to clients and recovery housing offering more services to a younger and “sicker” group of residents—altering the nature of what recovery housing looks like and does.

One way in which the introduction of recovery support services and other treatment elements may be altering the nature of recovery housing is through decreased adherence to aspects of the social model philosophy. The social model approach is largely a California phenomenon (Borkman et al. 1998), but social model programs in California evolved from Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) teachings and traditions, and these traditions are reflected in Oxford Houses and TCs, in addition to sober living houses in California. Although all house managers reported that their homes were “very much” 12-step oriented, none of the homes could be classified as a true social model program as assessed with the SMPS, largely due to low scores in the governance domain.

The notion of resident self-governance, rooted in the democratic traditions of AA, gives residents a share in leadership to help in fostering mutual responsibility for the home and the residents in it. The ways in which residents can have a share in the responsibility of the program are many (see Borkman 1998) and include residents having a role in creating, implementing, and enforcing house rules. None of the homes in this study had a residence council (or any other sort of resident governing body) and the majority of house managers reported that governance decisions were made by staff not residents. Although low scores in this domain could reflect an outmoded or California-centric way of measuring the concept of resident self-governance, it is also possible that lower scores in this domain reflect true drift in the value placed on self-governance in some types of recovery residences or a lack of understanding with respect to how to implement social model principles within recovery housing (Polcin et al. 2014). It may also be a reaction to other forces such as professionalization of the recovery housing modality or changes in the characteristics of the residents living in recovery housing. Indeed, even in California, there is evidence to suggest decreasing adherence to social model principles programs among programs that identify as “social model programs” (Kaskutas, Keller & Witbrodt 1999).

Professionalization and the wider integration of recovery support and treatment services may also affect recovery housing costs as well as opportunities to cover these costs. By sharing expenses and the responsibility of running houses that do not include the provision of services, recovery housing has generally existed as an affordable housing option for those in recovery who may still be in the process of securing employment and building financial and other recovery capital (Cloud & Granfield 2008). The organization operating the recovery homes in this study has been able to leverage revenue from insurance to cover operating costs, and there are residences in the US that receive funding through public resources (Mericle, Miles & Cacciola 2015), but recovery housing has historically been supported by the residents covering fees out-of-pocket, and funding is a common barrier to operating recovery housing (Mericle, Miles & Way 2015). Clearly more studies investigating the use of public and private insurance for recovery housing are needed, particularly in light of the evolving nature of services provided in recovery housing. Regardless, it remains critical to ensure recovery housing remain affordable for those without insurance coverage and to find ways to support recovery housing through public funding streams (e.g., substance use, housing, and/or criminal justice).

Safe and stable housing is integral to supporting a lifestyle in recovery and recovery housing represents an innovative way to augment and extend the substance use continuum of care. This work examines a group of recovery homes in Texas that represent a type of recovery housing that has been under-represented in the scientific literature and illustrates how recovery housing has adapted to meet the evolving needs of residents.

Several limitations of this study are important to note. First, this is a descriptive study of just 10 residences in one city in the US. It is unclear how common this treatment/recovery hybrid-type recovery housing may be in other cities across the US because there is no systematic surveillance of recovery housing. Second, there currently exists no comprehensive or standardized way to assess the characteristics of recovery residences to better understand how residences might be different from one another and from other types of substance use treatment or housing services. Although this study used measures that have been used in prior studies of recovery residences, findings from this work would be strengthened through the development an assessment tool to gather data on a wide range of recovery residences along dimensions identified by the field to be essential to characterizing and monitoring this service delivery modality, including additional information on sources of revenue (particularly the use of public and private insurance) to cover operating costs. Finally, the data used to characterize the neighborhoods in which homes were located were based on house managers’ perceptions rather than on estimates from more objective sources, like the US Census. Geocoding and linking house addresses with US Census data could provide additional information on neighborhood characteristics and potentially highlight differences between these characteristics and those of house managers’ and residents’ perceptions of their neighborhood. Research is also needed to assess why differences between various types of recovery housing or recovery housing in different geographic regions exist and whether positive findings with respect to recovery housing found previously hold for residences that serve different populations and with a different mix of support services.

Acknowledgments

Work on this manuscript was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21DA039027). The funding agencies had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDA or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Colleen Culton of Eudaimonia Recovery Homes as well as Thomasina Borkman at George Mason University and Jason Howell of the Texas Recovery-Oriented Housing Network for providing comments on early drafts of this manuscript and for their ongoing support of this study. Preliminary findings from this study were presented in a poster at the 2016 Addiction Health Services Research conferences held in Seattle, WA.

Footnotes

Recovery coaches must have knowledge of the recovery process, and peer recovery coach certification is encouraged.

References

- Borkman T. Resident self-governance in social model recovery programs. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1998;25(4):741–771. [Google Scholar]

- Borkman TJ, Kaskutas LA, Room J, Bryan K, Barrows D. An historical and developmental analysis of social model programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15(1):7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral health trends in the United States: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: 2015. [Accessed: 2016-03-01]. (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50) http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cloud W, Granfield R. Conceptualizing recovery capital: expansion of a theoretical construct. Substance Use and Misuse. 2008;43(12–13):1971–1986. doi: 10.1080/10826080802289762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leon G. Is the therapeutic community an evidence-based treatment? What the evidence says. Therapeutic Communities. 2010;31(2):104–128. [Google Scholar]

- De Leon G. The Therapeutic Community: Theory, model, and method. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK. Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice. 2007;4(1):45–55. doi: 10.1151/ascp074145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy P, Baldwin H. Recovery post treatment: plans, barriers and motivators. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2013;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyrich-Garg KM, Cacciola JS, Carise D, Lynch KG, McLellan AT. Individual characteristics of the literally homeless, marginally housed, and impoverished in a US substance abuse treatment-seeking sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2008;43(10):831–842. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari JR, Groh DR, Jason LA. The neighborhood environments of mutual-help recovery houses: comparisons by perceived socio-economic status. Journal of Groups in Addiction and Recovery. 2009;4(1–2):100–109. doi: 10.1080/15560350802712470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari JR, Jason LA, Blake R, Davis MI, Olson BD. ‘This is my neighborhood’: comparing United States and Australian Oxford House neighborhoods. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2006;31(1–2):41–49. doi: 10.1300/J005v31n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari JR, Jason LA, Davis MI, Olson BD, Alvarez J. Similarities and differences in governance among residents in drug and/or alcohol misuse recovery: self vs. staff rules and regulations. Therapeutic Communities. 2004;25(3):185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari JR, Jason LA, Sasser KC, Davis MI, Olson BD. Creating a home to promote recovery: the physical environments of Oxford House. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2006;31(1–2):27–39. doi: 10.1300/J005v31n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JO. Place and attrition from substance abuse treatment. Journal of Drug Issues. 2004;34(1):23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Mericle AA, Polcin DL, White WL. The role of recovery residences in promoting long-term addiction recovery. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;52(3–4):406–411. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, Ferrari JR, Lo Sasso AT. Communal housing settings enhance substance abuse recovery. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(10):1727–1729. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, Ferrari JR, Majer JM, Alvarez J, Stout J. An examination of main and interactive effects of substance abuse recovery housing on multiple indicators of adjustment. Addiction. 2007;102(7):1114–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Logan J, Gladden RM, Bohm MK. Vital Signs: Demographic and substance use trends among heroin users — United States, 2002–2013. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2015;64(26):719–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CK. Addiction epidemic fuels runaway demand for ‘sober homes’. Associated Press; Chicago: 2016. [Accessed: 2016-12-09]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6mdNgEyQC. [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Greenfield TK, Borkman TJ, Room J. Measuring treatment philosophy: a scale for substance abuse recovery programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Keller JW, Witbrodt J. Measuring social model in California: how much has changed? Contemporary Drug Problems. 1999;26(4):607–631. [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, Humphreys K. Promoting recovery in an evolving context: what do we know and what do we need to know about recovery support services? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;45(1):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, Stanick V, Sands B. What could the program have done differently? A qualitative examination of reasons for leaving outpatient treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37(2):182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, White W. What are your priorities right now? Identifying service needs across recovery stages to inform service development. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, Mason MJ. Social and geographic contexts of adolescent substance use: the moderating effects of age and gender. Social Networks. 2012;34(1):150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Mericle AA, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Gupta S, Sheridan DM, Polcin DL. Distribution and neighborhood correlates of sober living house locations in Los Angeles. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2016;58(1–2):89–99. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mericle AA, Miles J, Cacciola J. A critical component of the substance abuse continuum of care: recovery homes in Philadelphia. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(1):80–90. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.976726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mericle AA, Miles J, Cacciola J, Howell J. Adherence to the social model approach in Philadelphia recovery homes. International Journal of Self Help and Self Care. 2014;8(2):259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Mericle AA, Miles J, Way F. Recovery residences and providing safe and supportive housing for individuals overcoming addiction. Journal of Drug Issues. 2015;45(4):368–384. [Google Scholar]

- Molina KM, Alegría M, Chen CN. Neighborhood context and substance use disorders: a comparative analysis of racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125(Suppl 1):S35–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Recovery Residences. A brief primer on recovery residences: FAQ. Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Accessed: 2014-01-16]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Mg0GCoVM. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A research-based guide. 3. Baltimore, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health; 2012. [Accessed: 2014-01-22]. (NIH Publication No. 12–4180) Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6MpROYx6t. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson FS, Prendergast ML, Podus D, Vazan P, Greenwell L, Hamilton Z. Meta-analyses of seven of the NIDA’s principles of drug addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;43(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL. Sober Living Houses After, During, and as an Alternative to Treatment. Addiction Health Services Research Conference; Little Rock, AK. October 23–25.2006. [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Henderson DM. A clean and sober place to live: philosophy, structure, and purported therapeutic factors in sober living houses. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(2):153–159. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Korcha R, Bond J, Galloway G. Eighteen-month outcomes for clients receiving combined outpatient treatment and sober living houses. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2010;15(5):352–366. doi: 10.3109/14659890903531279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Korcha R, Bond J, Galloway GP. Sober living houses for alcohol and drug dependence: 18-month outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38(4):356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Mericle A, Callahan S, Harvey R, Jason LA. Challenges and rewards of conducting research on recovery residences for alcohol and drug disorders. Journal of Drug Issues. 2016;46(1):51–63. doi: 10.1177/0022042615616432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Mericle A, Howell J, Sheridan D, Christensen J. Maximizing social model principles in residential recovery settings. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46(5):436–443. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.960112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif S, George P, Braude L, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, Delphin-Rittmon ME. Recovery housing: assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(3):295–300. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room J, Kaskutas L. Social Model Philosophy Scale (SMPS): Manual. Guidelines for scale administration and interpretation: residential, non-residential & detoxification alcohol and drug programs, revised. Emeryville, CA: Alcohol Research Group; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Room J, Kaskutas LA, Piroth K. A brief overview of the social model approach. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1998;25(4):649–664. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths — United States, 2000–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;64(50–51):1378–1382. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: 2014. [Accessed: 2015-02-19]. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Working Definition of Recovery. Rockville, MD: 2012. [Accessed: 2015-07-31]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6aRHz0R8X. [Google Scholar]

- The Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel. What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Fact Sheet: The Opioid Epidemic - By the Numbers. Washington, DC: 2016. [Accessed: 2016-11-18]. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6m7JsuyjM. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderplasschen W, Colpaert K, Autriquem M, Rapp RC, Pearce S, Broekaert E, Vandevelde S. Therapeutic communities for addictions: a review of their effectiveness from a recovery-oriented perspective. The Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:22. doi: 10.1155/2013/427817. (Article ID 427817) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]