Abstract

Cell fusion–mediated formation of multinuclear osteoclasts (OCs) plays a key role in bone resorption. It is reported that 2 unique OC-specific fusogens [i.e., OC-stimulatory transmembrane protein (OC-STAMP) and dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP)], and permissive fusogen CD9, are involved in OC fusion. In contrast to DC-STAMP-knockout (KO) mice, which show the osteopetrotic phenotype, OC-STAMP-KO mice show no difference in systemic bone mineral density. Nonetheless, according to the ligature-induced periodontitis model, significantly lower level of bone resorption was found in OC-STAMP-KO mice compared to WT mice. Anti–OC-STAMP-neutralizing mAb down-modulated in vitro: 1) the emergence of large multinuclear tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase–positive cells, 2) pit formation, and 3) mRNA and protein expression of CD9, but not DC-STAMP, in receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL)-stimulated OC precursor cells (OCps). While anti–DC-STAMP-mAb also down-regulated RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis in vitro, it had no effect on CD9 expression. In our mouse model, systemic administration of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb suppressed the expression of CD9 mRNA, but not DC-STAMP mRNA, in periodontal tissue, along with diminished alveolar bone loss and reduced emergence of CD9+ OCps and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase–positive multinuclear OCs. The present study demonstrated that OC-STAMP partners CD9 to promote periodontal bone destruction by up-regulation of fusion during osteoclastogenesis, suggesting that anti–OC-STAMP-mAb may lead to the development of a novel therapeutic regimen for periodontitis.—Ishii, T., Ruiz-Torruella, M., Ikeda, A., Shindo, S., Movila, A., Mawardi, H., Albassam, A., Kayal, R. A., Al-Dharrab, A. A., Egashira, K., Wisitrasameewong, W., Yamamoto, K., Mira, A. I., Sueishi, K., Han, X., Taubman, M. A., Miyamoto, T., Kawai, T. OC-STAMP promotes osteoclast fusion for pathogenic bone resorption in periodontitis via up-regulation of permissive fusogen CD9.

Keywords: osteoclastogenesis, periodontal bone loss, mouse model, DC-STAMP, RANKL

Cell fusion is a characteristic of osteoclast precursor cells (OCps), which as a result become multinucleated mature osteoclasts (OCs). Only a few other cells, including oocytes and muscle cells, have this feature, but in these cells, cell fusion occurs at the developmental stage, while cell fusion of OCps occurs at the postdevelopmental stage. Therefore, it is plausible that targeting the cell fusion event in OCps could lead to the specific regimen that is able to down-modulate pathogenic bone resorption without causing unwanted adverse effects on other tissues and organs. Many molecules have been implicated in OC cell fusion (1), including transmembrane proteins that are thought to elicit the reorganization of cell membrane structure for cell–cell fusion. In particular, dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP) (2), OC-stimulatory transmembrane protein (OC-STAMP) (3–5), and CD9 (6, 7) are all reported to play essential roles in OC fusion.

Among a number of bone resorptive diseases, we are particularly interested in the pathophysiology of alveolar bone resorption caused in periodontitis which is mediated by a locally elevated osteoclastogenesis (OC-genesis) factor, namely receptor activator of NF-kB ligand (RANKL) (8–10), and which affects the 46% of the adult U.S. population (11). To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying pathogenic OC-genesis relative to OCp fusion in periodontitis, we showed that DC-STAMP is engaged in OCp fusion during OC-genesis, which in turn promotes local OC differentiation and bone resorption induced in a mouse model of periodontitis (12). Although increased CD9 immunostaining patterns were demonstrated in neutrophils and epithelium in gingival crevice of patients with periodontitis (13), the possible functions of CD9 expressed by OCs in the alveolar bone of periodontal lesion are largely unknown. To our knowledge, no studies have addressed the expression of OC-STAMP and its biologic role in the context of periodontitis.

DC-STAMP and OC-STAMP are both induced during the fusion processes of RANKL-elicited OC-genesis (3). On the basis of its putative multispanning transmembrane structure (3), DC-STAMP is thought to belong to the GPCR superfamily (14). OC-STAMP is also thought to belong to the GPCR family on the basis of its homology with DC-STAMP (3). While OCps isolated from both DC-STAMP-knockout (KO) and OC-STAMP-KO mice are incapable of generating mature multinucleated OCs in response to RANKL stimulation in vitro, only DC-STAMP-KO mice, but not OC-STAMP-KO mice, show the osteopetrotic bone phenotype in adult mice (5). Furthermore, anti–DC-STAMP-mAb administered to the mice with induced periodontitis showed partial suppression (20–30%) of periodontal bone resorption by down-regulating the cell fusion of OCps (15), suggesting the presence of some additional mechanism that up-regulates the fusion of OCps. Collectively, these studies indicate that each STAMP plays a distinct role in OC-genesis–mediated bone remodeling. Nonetheless, because no studies have yet examined the susceptibility of OC-STAMP-KO mice for developing bone lytic diseases, including periodontitis, these published results do not preclude the possibility that OC-STAMP may facilitate OC-genesis in a pathogenic context. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether the 2 STAMPs are engaged in OCp fusion dependently or independently in the context of periodontitis.

The third putative OC fusogen, CD9, is well known to promote muscle-cell fusion and myotube homeostasis (16, 17). Fertility in CD9-deficient female mice is severely reduced because oocytes are unable to fuse with sperm on fertilization (18, 19), suggesting that CD9 plays a key role in egg–sperm fusion during mammalian fertilization. Important to this study, it is reported that CD9 expressed on OCs is engaged in their fusion (6, 7) and that expression of CD9 is prominently elevated in OCs in the bone resorption lesions of osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis induced in mice (20). Again, however, the molecular mechanism that promotes CD9 expression in OCps remains elusive in relation to OC-STAMP and DC-STAMP.

Therefore, the present study examined the molecular mechanism underlying OC-STAMP–dependent OC cell fusion in association with CD9 and DC-STAMP, while establishing the role of OC-STAMP in the alveolar bone resorption induced in a mouse model of ligature-induced periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6J mice were bred and kept in a conventional room with a 12-h light–dark cycle at a constant temperature. OC-STAMP-KO mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (018707, OC-STAMPtm2b(KOMP)Wtsi; Bar Harbor, ME, USA), and heterozygous male and female mice were mated to generate homozygous OC-STAMP-KO mice. All experiments using OC-STAMP-KO mice were carried out using homozygotes. The experimental procedures used in this study were approved by the Forsyth Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In vitro OC-genesis assay

Mononuclear bone marrow (BM) cells were isolated from femur and tibia of C57BL/6J mice (8–12 wk old males) by the density gradient centrifugation method using Histopaque 1083 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The resulting BM single-cell suspensions were seeded into 96-well plates (105 cells per well) in α-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 20 ng/ml M-CSF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). After incubation for 2 d, 100 µl of the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing M-CSF (20 ng/ml) and murine soluble RANKL (50 ng/ml; R&D Systems). Some cultures received different concentrations of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb (mouse IgG3), anti–DC-STAMP-mAb (mouse IgG2a) (12), anti–CD9-mAb (clone KMC8, rat IgG; BD Pharmingen, Chicago, IL, USA), irrelevant mouse mAb (IgG3 and IgG2a), or nonimmunized rat IgG. Differentiated OCs were identified by their expression of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) using a leukocyte acid phosphatase staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. TRAP+ multinuclear cells containing 3 nuclei or more were counted microscopically.

Design of anti–OC-STAMP-mAbs

We have recently developed an anti–DC-STAMP-mAb (mouse IgG2a) that can neutralize the cell fusion event in RANKL-induced OCs (12). Anti–OC-STAMP-mAb (mouse IgG3) was generated by the methods previously reported (21–23). Briefly, 8 wk old BALB/c mice were immunized with highly specific peptide sequences of mouse OC-STAMP protein (OC-STAMP peptide: FASMQRSFQWELRFTPHDCHLPQAQPPR), which were designed using a BLAST search. The binding of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb to OC-STAMP peptide on the ELISA plate was only inhibited by OC-STAMP peptide, but not by DC-STAMP peptide or control irrelevant peptide sequences. In Western blot analysis using M-CSF/RANKL-stimulated mouse BM cells, the positive band (55 kDa), as detected by anti–OC-STAMP-mAb, was blocked by the presence of OC-STAMP peptide, while the irrelevant mAb (IgG3, clone BF116BF1.2; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA) did not show any reactivity to the same sample.

Pit formation assay

BM cells were preincubated with M-CSF (30 ng/ml) alone for 2 d, followed by stimulation with M-CSF (30 ng/ml) and RANKL (100 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb or control mAb (BF116BF1.2) in a 96-well Osteo Assay Surface plate (Corning, Corning, NY, USA). Seven days after RANKL addition, the plates were washed with sodium hypochlorite and air dried. Wells were imaged with a ×4 objective using the Evos cell imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Image analysis was carried out with ImageJ software (Image Processing and Analysis in Java; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; http://imagej.nih.gov/).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

OCps cultured on a glass coverslip were stained with appropriate fluorescence-labeled reagents, followed by image capture with a Zeiss LSM780 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). FcR were blocked by incubation with anti-CD16/32 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) in 1% bovine serum albumin/PBS for 1 h at 4°C. After incubation of cells with Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated anti–OC-STAMP-mAb, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, the cells were reacted with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated phalloidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and counterstained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope.

Flow cytometry

OCps were preincubated for 72 h in culture medium containing M-CSF. Then, at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after the addition of soluble RANKL, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells cultured in a 25 cm2 flask were removed by incubation with 1 mM EDTA for 1 h. After blocking FcR with anti-CD16/32 mAb (BioLegend), the cells were stained with FITC-labeled anti–DC-STAMP-mAb (15), either Alexa Fluor 546– or Alexa Fluor 647–labeled anti–OC-STAMP, phycoerythrin-labeled anti–CD9-PE-mAb (BD Pharmingen), and APC-labeled anti–CD115-mAb (BioLegend) for 1 h. OCps reacted with respective mAb were then subjected to flow cytometry analysis using the FACSAria III system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using RNA-Bee isolation reagent (AMS Biotechnology, Cambridge, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and subjected to reverse transcription with the Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the presence of random primers and oligo-dT. Gene expression was quantified using the LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The primer sequences used in this study were as follows: CD9 forward: 5′-GTACCATGCCGGTCAAAGGA-3′, reverse: 5′-CCCGGCTCCAATCAGAATGT-3′; DC-STAMP forward: 5′-TCCTCCATGAACAAACAGTTCCAA-3′, reverse: 5′-AGACGTGGTTTAGGAATGCAGCTC-3′; OC-STAMP forward: 5′-ATGAGGACCATCAGGGCAGCCACG-3′, reverse: 5′-GGAGAAGCTGGGTCAGTAGTTCGT-3′; and GAPDH forward: 5′-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3′, reverse: 5′-ATGCAGGGATGATGTTCTGG-3′. Simultaneously amplified GAPDH gene was used as an internal control.

Mouse model of ligature-induced periodontitis

OC-STAMP-KO mice (The Jackson Laboratory) or wild-type (WT) mice (6–8 wk old, C57BL/J male, n = 5–6) were placed with a 5-0 silk ligature (Ethicon, Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, USA) on the upper left second molar, whereas the upper right second molar without ligature was used as a control, following the protocol that was developed by our group (12, 24–27). Because we used mice raised from different breeding cages, especially those of OC-STAMP-KO strains, to avoid the effect of different oral flora, the male mice used for the experiment were cohoused for a week so that all mice harbored similar oral flora, following the protocol reported by other groups (28, 29). Immediately after the attachment of ligature, some mice received systemic injection of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb (5 mg/mouse, i.p.) or control mAb (5 mg/mouse, i.p.). Seven days after ligature placement, gingival tissue and jawbone, including periodontal tissue, were collected from humanely killed mice for real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR), alveolar bone measurement, and immunohistochemistry. The sample size (n = 5) was determined on the basis of 80% power at .05 significance. In some experiments, we used n = 6 to increase the statistical power.

Alveolar bone resorption measurement

The maxillary jaws were collected from humanely killed mice. Ligatures were removed, and the maxillae were defleshed using dermestid beetles (30). Alveolar bone resorption was measured as previously described (12, 24–27, 31). Briefly, the distance from the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) to the alveolar crest (AC) on the buccal side of each root was measured with a dissection microscope. Total alveolar bone loss was calculated by summing CEJ-AC distances of distal root of first molar; mesial, midbuccal, and distal root of second molar; and mesial root of third molar. The measurements of bone loss were performed by a calibrated examiner in a blinded manner. It is noteworthy that the measurement of bone loss using a dissection microscope is as accurate as bone volume measured by micro–computed tomography [correlation efficient, R = −0.871, n = 18, from data in Wisitrasameewong et al. (12)].

Measurement of bone mineral density using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

After the collection of jawbone, femurs were surgically removed from humanely killed mice on d 7. Femoral bone mineral density was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry using a Lunar Piximus densitometer (GE Medical Systems, Wauwatosa, WI, USA). Data were expressed as milligrams per square centimeter.

Preparation of gingival tissue homogenates for RANKL/osteoprotegerin ELISA

As previously described (32, 33), gingival tissues were homogenized with a Dounce glass homogenizer in PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween 20, PMSF (1 mM; Sigma-Aldrich), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Soluble RANKL and osteoprotegerin (OPG) levels in tissue homogenates were determined using commercially available ELISA kits (DuoSet ELISA; R&D Systems).

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry and TRAP staining of periodontal tissue isolated from mice

Mice maxillae were dissected and fixed in 10% formaldehyde overnight at 4°C. The specimens were then washed in PBS and decalcified in 10% EDTA for 3 wk at 4°C. Decalcified samples were embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and sectioned (7 µm thick) with a cryostat. The resulting sections were mounted on a glass slide and stained using the Acid Phosphatase, Leukocyte (TRAP) Kit (Sigma-Aldrich), as previously described (32). The slides were then counterstained with 1% methyl green. For fluorescent immunohistochemistry to detect CD9+ and CD115+ cells in the periodontal tissue of mice, the specimens were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound. The sections were reacted with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti–CD9-mAb and Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated anti–CD115-mAb, followed by counterstaining with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After extensive washing, the stained sections were mounted with Fluoromount-G medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunofluorescence was observed with a Zeiss LSM780 Confocal Microscope.

Statistical analysis

All in vitro assays were conducted at least in triplicate, and each study was repeated 3 times. All quantitative data in the figures are shown as means ± sd. The collected data were analyzed by Student’s t test for comparison between 2 groups, or by 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test for comparisons among different groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

OC-STAMP-KO mice showed diminished alveolar bone loss in ligature-induced mouse model of periodontitis

It was reported that only DC-STAMP-KO mice, but not OC-STAMP-KO mice, show the osteopetrotic bone phenotype, whereas OCps isolated from both DC-STAMP-KO and OC-STAMP-KO mice cannot generate mature multinucleated OCs in response to RANKL stimulation in vitro (5). Even though OCps isolated from OC-STAMP-KO mice cannot form mature, multinucleated OCs, it is still conceivable that they may show bone phenotype in the pathogenic state, but not in the homeostatic bone remodeling state. To confirm this, the present study examined if OC-STAMP-KO mice, compared to their WT mice, would show difference in susceptibility of developing bone resorption lesion in periodontitis.

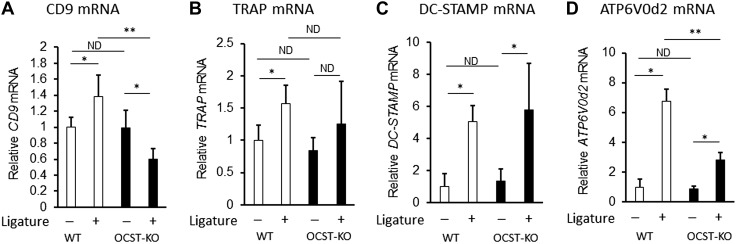

Experimental periodontitis was induced by an attachment ligature around teeth for the accumulation of bacteria. This is one of the most reproducible and commonly used mouse periodontitis models (34, 35). OC-STAMP-KO mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory showed a level of bone mineral density in femur comparable to their control WT mice (Supplemental Fig. 1), suggesting that homeostatic bone remodeling proceeded normally in these mice, corresponding to the report by Miyamoto et al. (5). However, OC-STAMP-KO mice showed significantly diminished periodontal bone loss (CEJ-AC distance) compared to the control WT mice (Fig. 1A). Importantly, no statistically significant difference was detected in the CEJ-AC distance at the control no-ligature side of both strains of mice (Fig. 1A), indicating that initial qualities of alveolar bone are equivalent between OC-STAMP-KO and WT mice. Histologic analysis of OCs in the alveolar bone demonstrated that significantly larger number of TRAP+ OCs was detected on the periodontitis induced in WT mice than that induced in OC-STAMP-KO mice (Fig. 1B). According to qPCR-based gene expression profiling (Fig. 2), the attachment of ligature increased the expression of mRNAs for TRAP, DC-STAMP, CD9, and ATPase H+ transporting V0 subunit d2 (ATP6V0d2) in the WT mice. Because it is reported that ATP6V0d2 along with DC-STAMP is engaged in NFATc1-mediated OC cell fusion (36, 37), ATP6V0d2 mRNA expression was investigated. The expressions of mRNAs for DC-STAMP and ATP6V0d2 were induced by ligature in the OC-STAMP-KO mice, whereas, interestingly, expression level of CD9 mRNA decreased by ligature attachment (Fig. 2). The total levels of mRNAs for CD9 and ATP6V0d2 detected in OC-STAMP-KO mice that received a ligature attachment was significantly lower than those mRNA detected in ligature-attached WT mice. Importantly, the mRNA level of DC-STAMP did not show any significant difference between OC-STAMP-KO and WT mice before or after the attachment of ligature. These data indicated that OC-STAMP is associated with the pathogenic periodontal bone resorption by up-regulation of OC-genesis in a manner independent of DC-STAMP.

Figure 1.

OC-STAMP-KO mice showed diminished alveolar bone loss in ligature-induced mouse model of periodontitis. A) Alveolar bone resorption induced in mice by attachment of ligature. Total alveolar bone loss was calculated by summing CEJ-AC distances of distal root of first molar; mesial, midbuccal, and distal, root of second molar; and mesial root of third molar. Seven days after ligature attachment, OC-STAMP KO demonstrated significantly diminished level of periodontal bone loss compared to WT mice [WT: n = 6, OC-STAMP-KO: n = 5, means ± sd. *P < 0.05, no difference (ND)]. B) Frozen sections of decalcified maxilla isolated from humanely killed mice (d 7) were subjected to TRAP staining. Scale bars, 50 µm. C) Histogram showing numbers of TRAP+ OCs counted in section (means ± sd. *P < 0.05, ND).

Figure 2.

Expression profile of gene-associated OC cell fusion in OC-STAMP-KO and WT mice. CD9 (A), TRAP (B), DC-STAMP (C), and ATP6V0d2 (D) mRNA were measured by qPCR in periodontal tissue sampled from site that received ligature and control site without ligature from WT and OC-STAMP-KO mice on d 3 [WT: n = 4, OC-STAMP-KO: n = 4. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, no difference (ND)]. All data shown in histograms are means ± sd.

Expression pattern of OC-STAMP in RANKL-stimulated OCps isolated from mouse BM

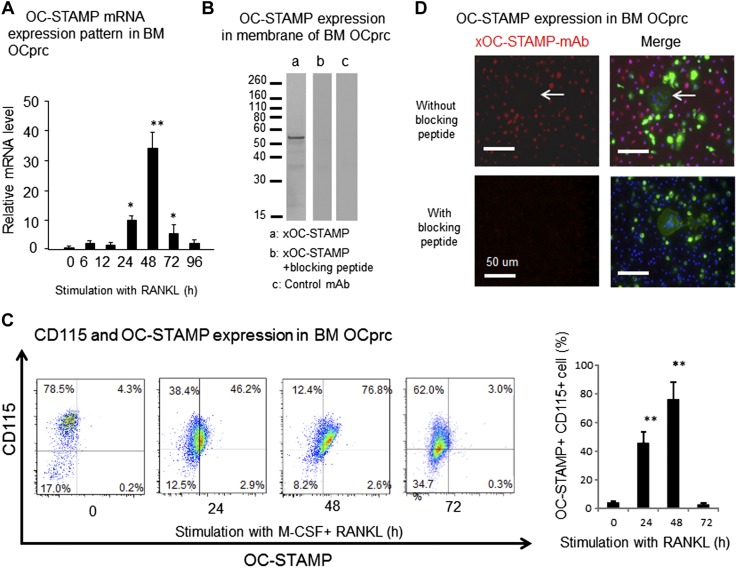

In order to establish the role of OC-STAMP in RANKL-induced OC-genesis, an OC-genesis assay was performed in vitro using primary culture of BM cells isolated from WT mice. According to qPCR, after stimulation of OCps with RANKL, expression of OC-STAMP mRNA increased with time, peaked at 48 h, and then gradually decreased (Fig. 3A). We have developed an anti-mouse OC-STAMP-Ab that recognizes the epitope in the third extracellular loop of OC-STAMP protein. OC-STAMP expression on the cell membrane of OCps stimulated with RANKL for 2 d was detected by xOC-STAMP-mAb (IgG3) in Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B). The addition of blocking peptide during the incubation of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb with nitrocellulose membrane transblotted with OCp protein inhibited the reaction of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb with OC-STAMP protein in Western blot analysis. The control mAb (IgG3, clone 116BF1.2) showed no reaction to any OCp protein in Western blot analysis. Furthermore, anti–OC-STAMP-mAb recognized mouse OC-STAMP overexpressed on NIH-3T3 cells, the binding of which was inhibited in the presence of specific blocking peptide but not irrelevant peptide (Supplemental Fig. 2), suggesting that anti–OC-STAMP-mAb developed in this study binds to the OC-STAMP expressed on cell surface in a target-specific fashion. Expression of OC-STAMP protein on the surface of primary culture of OCps isolated from mouse BM was analyzed with a flow cytometer (Fig. 3C). Consistent with qPCR results (Fig. 3A), expression of OC-STAMP protein was induced on the cell surface by stimulation with RANKL, with peak expression at 48 h after stimulation (Fig. 3C). According to the fluorescence immunostaining of RANKL-stimulated OCps in vitro (Fig. 3D), OC-STAMP expression was only detected in mononuclear OCps, suggesting the possible association of OC-STAMP with cell fusion.

Figure 3.

Expressions of OC-STAMP mRNA and protein in RANKL-stimulated BM-derived OCps in vitro. In order to induce CD115+ OCps, mononuculear cells isolated from mouse BM were preincubated with M-CSF (20 ng/ml) for 3 d and then used for following experiments. A) According to qPCR, OC-STAMP mRNA expression was induced in OCps derived from BM by stimulation with RANKL (50 ng/ml). Peak expression of OC-STAMP mRNA was detected at 48 h, followed by gradual reduction. B) OCps derived from BM were stimulated in vitro with RANKL for 3 d. Cell membrane fraction isolated from cultured OCps was subjected to SDS-PAGE. After transblotting to nitrocellulose membrane, biotinylated anti–OC-STAMP-mAb (1 μg/ml) was reacted to membrane. Positive band reactive to anti–OC-STAMP-mAb was detected at MW 56 kDa (a). In same Western blot experiment, addition of blocking peptide, which was used as immune antigen for generation of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb, inhibited development of positive band reactive to anti–OC-STAMP-mAb (b). Isotype-matched control mAb did not show any positive reaction by Western blot (c). C) Temporal change of OC-STAMP expressed on RANKL-stimulated OCps was evaluated by flow cytometry. OCps were stimulated with RANKL for 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. After reaction with Alexa Fluor 546–labeled anti–OC-STAMP-mAb and Alexa Fluor 647–labeled anti-CD115 (M-CSF)-mAb, RANKL-stimulated OCps were subjected to flow cytometry. Histogram shows incidence (%) of OC-STAMP+ OCps among CD115+ OCps. D) Expression of OC-STAMP protein on RANKL-stimulated OCps was monitored by Alexa Fluor 647–labeled anti–OC-STAMP-mAb, along with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated phalloidin and DAPI, which stain actin fiber and nuclei, respectively, by laser scanning confocal microscope. Red, OC-STAMP; green, F-actin; blue, nuclei. Scale bars, 50 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared to 0 h (statistically significantly different, by Tukey’s test).

Effects of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb on RANKL-induced OC-genesis in vitro

Yang et al. (4) demonstrated that rabbit pAb that reacts to 180 C-terminal peptides of mouse OC-STAMP could suppress the induction of RANKL-induced TRAP+ multinuclear OC from mouse RAW264.7 OCps in vitro. In this study, anti–OC-STAMP-mAb was generated by immunization of mice with the 28 aa sequence of mouse OC-STAMP protein, which is present in the above-noted 180 C-terminal peptides. More specifically, this 28 aa sequence was selected from the third extracellular loop structure determined by the analysis of OC-STAMP topology (3). Therefore, it seemed likely that anti–OC-STAMP-mAb would show activity similar to that of rabbit pAb generated by Yang et al. (4). Indeed, as expected, anti–OC-STAMP-mAb did suppress RANKL-induced differentiation of TRAP+ multinuclear OC from M-CSF–primed BM cells (Fig. 4A). This effect was more evident in large TRAP+ multinuclear OC (>10 nuclei/cell) than small TRAP+ multinuclear OC (10 ≥ nuclei/cell > 3) (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the cell fusion event might be down-regulated by anti–OC-STAMP-mAb. In the pit formation assay, anti–OC-STAMP-mAb also down-regulated pit resorption caused by RANKL-stimulated OCs (Fig. 4C). These results indicated that the anti–OC-STAMP-mAb could neutralize the biologic function of OC-STAMP as a promoter of OC-genesis and that OC-STAMP might indeed be associated with cell fusion as well as with bone resorption activity in the course of pathogenic RANKL-induced OC-genesis.

Figure 4.

Effects of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb on RANKL-induced OC-genesis in vitro. OCps derived from BM cells were stimulated with RANKL in presence or absence of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb or control mAb for 7 d, and TRAP staining was performed. A) Images of TRAP staining for RANKL-stimulated OCps. Scale bars, 50 μm. B) Number of TRAP+ multinuclear OCs was calculated. Based on number of nuclei in each OC, OCs were classified into large OCs (>10 nuclei/cell) and small OCs (10 ≥ nuclei/cell > 3). C) OCps were incubated in presence or absence of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb or control mAb for 7 d in Corning Osteo Assay Surface plate for 7 d. Control group received no conditioned media. Pit area in each well was quantified by ImageJ software. Data are means ± sd (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (statistically significantly different, by Tukey’s test).

Effects of OC-STAMP on expressions of CD9 and DC-STAMP during in vitro RANKL-stimulated OC-genesis

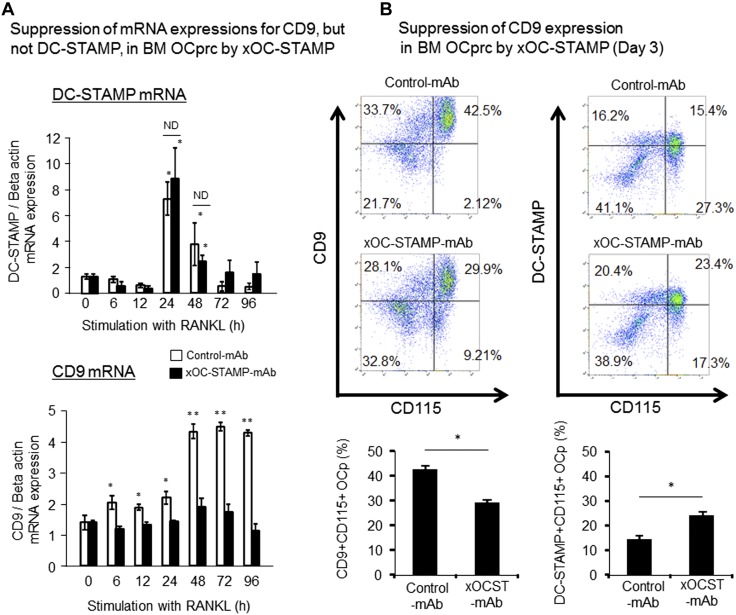

In order to establish the role of OC-STAMP in promoting RANKL-mediated OC-genesis in relation to cell fusion, the possible effects of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb on induction of other fusogens, i.e., CD9 and DC-STAMP, in RANKL-stimulated OCps, were examined in vitro. According to the results from qPCR and flow cytometry, anti–OC-STAMP-mAb suppressed the expression of CD9, but not DC-STAMP, at both the mRNA (Fig. 5A) and protein (Fig. 5B) levels, respectively. More specifically, RANKL-mediated up-regulation of CD9 mRNA in OCps was inhibited in the presence of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb. However, RANKL-mediated DC-STAMP mRNA expression in OCps, which showed a peak at 24 h, was not affected by the presence of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb (Fig. 5A). The distinct suppression effects of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb on the expression of CD9 mRNA, but not DC-STAMP mRNA, were further confirmed by their translation into the respective protein expressions on the cell surface of RANKL-stimulated OCps, as monitored by flow cytometry (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Effects of OC-STAMP on expression of CD9 and DC-STAMP during in vitro RANKL-stimulated OC-genesis. After preincubation with M-CSF (20 ng/ml) for 3 d, mononuclear cells isolated form BM were stimulated with RANKL (50 ng/ml) and M-CSF (20 ng/ml) in presence or absence of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb or control mAb for 3 d, and temporal changes of mRNA and cell surface expression of DC-STAMP and CD9 were examined. A) In response to stimulation with RANKL, OCps increased expression of DC-STAMP mRNA, which reached peak at 24 h, followed by gradual reduction with time. However, no significant difference was observed in level of DC-STAMP mRNA between groups treated with anti–OC-STAMP-mAb and control mAb at 24 and 48 h. Statistically significantly different at *P < 0.05 by Tukey’s test, compared to 0 h; ND, no significant difference. B) Cell surface expressions of CD9 and DC-STAMP on OCps stimulated with RANKL in presence or absence of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb or control mAb for 3 d were monitored using flow cytometer. Data in histograms show means ± sd of CD9+CD115+ double-positive cells among mononuclear cells. Statistically significantly different at *P < 0.05 or ND by Tukey’s test (n = 3/group).

OCps of OC-STAMP-KO mice did not increase CD9 expression in response to RANKL stimulation

CD9 mRNA expression was attenuated in the periodontal tissue of OC-STAMP-KO mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 2D), and anti–OC-STAMP-mAb suppressed the expression of CD9 by RANKL-stimulated OCps in vitro (Fig. 5). However, it remains to be elucidated whether OCps in OC-STAMP-KO mice show diminished CD9 expression in response to stimulation with RANKL. To address this question, an OC-genesis assay was performed in vitro using the primary culture of BM cells isolated from OC-STAMP-KO mice (Fig. 6A). As reported by Miyamoto et al. (5), in contrast with the large number of TRAP+ multinuclear OCs induced in RANKL-stimulated OCps of WT mice, OCps of OC-STAMP-KO mice showed only a small number of TRAP+ multinuclear OCs in response to RANKL stimulation for 7 d (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, although anti–OC-STAMP-mAb suppressed the development of TRAP+ multinuclear OCs isolated from WT OCps, anti–OC-STAMP-mAb did not affect the development of TRAP+ multinuclear OCs isolated from OC-STAMP-KO mice. OCps stimulated with RANKL for 3 d were subjected to flow cytometry for the detection of CD9 expression (Fig. 6B). Results confirmed that WT OCps showed increased CD9 expression in response to stimulation with RANKL for 3 d, whereas OCps derived from OC-STAMP-KO mice showed no such increase of CD9 expression after stimulation with RANKL for 3 d (Fig. 6B). Therefore, it appears that OCps of OC-STAMP-KO mice do not express CD9 in response to RANKL stimulation.

Figure 6.

CD9 expression on RANKL-stimulated OCps isolated from OC-STAMP-KO mice. OCps derived from BM cells of WT and OC-STAMP-KO mice were stimulated with RANKL in presence or absence of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb or control mAb. TRAP staining for differentiated OCs on d 7 (A) and flow cytometry for detection of CD9 expressed on OCps on d 3 (B) were carried out. Data in histograms show means ± sd of TRAP+ multinuclear OCs (A) and CD9+CD115+ double-positive cells among mononuclear cells (B). Statistically significantly different at *P < 0.05 or no difference (ND) by Tukey’s test (n = 3/group).

OC-STAMP/CD9 axis promoted OC-genesis in a manner independent of DC-STAMP

According to qPCR results, anti–DC-STAMP-mAb did not affect CD9 mRNA expression in RANKL-stimulated OCps (Fig. 7A), indicating that, unlike OC-STAMP, DC-STAMP is not associated with CD9 mRNA expression. All mAbs tested, i.e., anti–CD9-mAb, anti–DC-STAMP-mAb, and anti–OC-STAMP-mAb, suppressed the emergence of RANKL-induced TRAP+ multinuclear cells (Fig. 7B). Additive inhibitory effects on the suppression of large OCs resulted from the combination of anti–CD9-mAb and anti–DC-STAMP-mAb. However, the combination of anti–CD9-mAb and anti–OC-STAMP-mAb did not show such suppressive effects on the emergence of large OCs (Fig. 7B, C). Small OCs also showed a similar response pattern to each mAb-mediated inhibition compared to the large OCs, while the magnitude of additive effects appeared to be less than that found in the large OCs. These results indicated that DC-STAMP did not affect CD9-mediated OC fusion and that it is engaged in the promotion of OC-genesis in a manner independent of the OC-STAMP/CD9 axis.

Figure 7.

Anti–DC-STAMP-mAb, but not anti–OC-STAMP-mAb, showed additive effects on anti–OC-STAMP-mAb–mediated suppression of formation of large TRAP+ OCs. A) OCps derived from BM cells of WT mice were stimulated with RANKL in presence or absence of anti–DC-STAMP-mAb or control mAb, and expression of CD9 mRNA was monitored by qPCR. Significantly elevated CD9 mRNA expression was detected 72 and 96 h after RANKL stimulation at 0 h. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Tukey’s test). No difference (ND) in CD9 mRNA was detected between groups treated with anti–DC-STAMP-mAb and control mAb. B) OCps stimulated with RANKL in presence or absence of anti–CD9-mAb, anti–DC-STAMP-mAb, and anti–OC-STAMP-mAb for 7 d were stained for TRAP expression. C) Number of small OCs (10 ≥ nuclei/cell > 3) and large OCs (>10 nuclei/cell) in assay (B) were counted and are presented in histograms. Tukey’s test, compared to stimulation with RANKL alone. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 (statistical difference between 2 columns by Tukey’s test).

OC-STAMP is engaged in pathogenic periodontal bone resorption in association with elevated CD9 expression in infiltrating OCps

It is reported that TRAP+ OCs found on the periosteal surface of OC-STAMP-KO mice are mononuclear cells, compared to WT mice, which show multinuclear TRAP+ OCs (3), suggesting that the cell-fusion property of OCs is attenuated intrinsically in OC-STAMP-KO mice. Therefore, in order to evaluate the role of OC-STAMP in pathogenic alveolar bone resorption induced in periodontitis mediated by multinuclear TRAP+ OCs (15, 27), the effects of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb on a mouse model of ligature-induced periodontitis was evaluated using WT mice. The induction of periodontitis by the attachment of ligature induced OC-STAMP mRNA expression in the periodontal tissue, and systemic administration of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb did not affect the expression of OC-STAMP mRNA in the gingival tissue–induced periodontitis (Fig. 8A). At the same time, the level of RANKL and OPG mRNAs produced in the gingival tissue of ligatured side showed no difference between the treatments with anti–OC-STAMP-mAb and control mAb, indicating that the same level of OC-genesis activation is induced in both groups (Fig. 8B). However, systemic administration of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb significantly suppressed alveolar bone resorption in this mouse model compared to control mAb (Fig. 8C). According to histologic evaluation of TRAP+ OCs in alveolar bone, administration of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb suppressed the emergence of TRAP+ OCs on the alveolar bone surface compared to the group that received control mAb (Fig. 8D; low-magnification image is shown in Supplemental Fig. 3). These results show that anti–OC-STAMP-mAb did suppress local OC-genesis but did not affect the local production of RANKL in the gingival tissue that received a ligature attachment. Thus, it can be concluded that OC-STAMP is associated with the process of OC differentiation, but not the production of OC-genesis factor RANKL.

Figure 8.

xOCSTAMP-mAb suppressed periodontal bone loss induced in ligatured experimental mice. Mice (6–8 wk old, males, C57BL/6J, n = 5/group) received silk ligature on upper left second molar, whereas upper right second molar without ligature was used as control. Immediately after attachment of ligature, mice received systemic injection of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb (5 mg per mouse, i.p.) or control mAb (5 mg per mouse, i.p.). A) Seven days after ligature placement, gingival tissue was collected from humanely killed mice for detection of OC-STAMP mRNA using qPCR. B) Expression levels of RANKL mRNA and OPG mRNA detected in gingival tissue (d 3 and 7) were expressed as RANKL/OPG mRNA ratio. C) Images of defleshed alveolar bones from humanely killed mice (d 7) are shown from buccal aspect. Scale bar, 1 mm. Quantitative data of bone loss (d 7) are shown in histogram. D) Frozen sections of decalcified maxilla isolated from humanely killed mice (d 7) were subjected to TRAP staining. Scale bars, 100 µm. Low-magnification image is shown in Supplemental Fig. 3. Histogram shows numbers of TRAP+ OCs counted in section (means ± sd, n = 5). **P < 0.01. Column and bar data indicate means ± sd. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (statistically significant differences, by Tukey’s test).

The mRNA levels for CD9, but not DC-STAMP, in the gingival tissue that received ligature were significantly suppressed by the systemic administration of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb compared to control mAb treatment (Fig. 9A). Finally, according to immunofluorescence evaluation, the number of CD9+ cells among CD115+ OCps on the alveolar bone surface of ligature-induced periodontitis was significantly lower in the group that received anti–OC-STAMP-mAb compared to control mAb (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, local administration of anti–CD9-mAb suppressed the bone resorption induced in WT mice by the attachment of ligature (Supplemental Fig. 4), indicating that neutralization of CD9 can suppress periodontal bone resorption. These results indicated that anti–OC-STAMP-mAb could suppress the expression of CD9 on OCps in the lesion of periodontitis induced in mice, confirming the findings from the in vitro experiments.

Figure 9.

Effects of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb on expression of CD9 in periodontal tissue of induced periodontitis. A) At d 3 and 7 after attachment of ligature, periodontal tissue was isolated from humanely killed mice, and mRNA levels for DC-STAMP and CD9 were monitored by qPCR (Fig. 8A). B) Decalcified jaw sections were subjected to fluorescent microscopy to detect CD9+ cells among CD115+ OCps on alveolar bone surface of ligature-induced periodontitis. Column and bar data indicate means ± sd of CD9+/CD115+ double-positive cells in microscopic area (100 × 100 μm). *P < 0.05 (statistically significant difference, by Tukey’s test).

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the absence of bone phenotype in the femur of OC-STAMP-KO mice, the present study demonstrated that OC-STAMP is not associated with homeostatic bone remodeling. On the other hand, diminished level of ligature-induced periodontal bone resorption found in OC-STAMP-KO mice indicated that OC-STAMP is engaged in pathogenic periodontal bone destruction. This was further confirmed by anti–OC-STAMP-mAb–mediated suppression of ligature-induced periodontal bone loss (about 50% suppression; Fig. 8) in mice. Supporting our finding, the absence of bone phenotype in OC-STAMP-KO mice, compared to DC-STAMP-KO mice that show osteopetrotic phenotype, was originally discovered by Miyamoto et al. (5). We recently reported that DC-STAMP is engaged in the periodontal bone resorption induced in the mouse model of ligature-induced periodontitis (15). More specifically, anti–DC-STAMP-mAb partially suppressed (about 25% suppression) periodontal bone loss induced in mice by the attachment of ligature (15), indicating that an additional mechanism is engaged in pathogenic periodontal bone resorption. Such findings and report could therefore suggest the possibility that 1) OC-STAMP is engaged in pathogenic bone remodeling, 2) DC-STAMP is involved in both homeostatic and pathogenic bone remodeling processes, and 3) OC-STAMP appears to be involved in pathogenic bone resorption to a greater degree compared to DC-STAMP.

Herein, we revealed that OC-STAMP may indeed play a role in promoting OC fusion via up-regulation of the fusogen CD9 expressed on OCps. This conclusion is based on the results that showed that 1) anti–OC-STAMP-mAb suppressed the development of large OC (>10 nuclei/cell) more than small OC (≥ 10 nuclei/cell > 3), 2) anti–OC-STAMP-mAb down-regulated expression of CD9 on RANKL-stimulated OCps, and 3) anti–OC-STAMP-mAb, as well as anti–CD9-mAb, suppressed RANKL-induced OC-genesis, respectively, while the combination of anti–OC-STAMP-mAb and anti–CD9-mAb showed neither synergistic nor additive effects on the suppression of OC-genesis. Interestingly, the expression of DC-STAMP mRNA in RANKL-stimulated OCps was not affected by KO of OC-STAMP gene or mAb-mediated OC-STAMP neutralization, suggesting that OC-STAMP–mediated promotion of OC fusion does not involve DC-STAMP. Furthermore, according to in vivo experiments, mAb-based neutralization of OC-STAMP inhibited the mRNA expression of CD9, but not DC-STAMP, in the periodontitis lesion induced in mice, which in turn suppressed the pathogenic alveolar bone loss induced in the mice. Thus, this study, for the first time, suggested the possible engagement of an OC-STAMP/CD9 axis in pathogenic OC fusion, resulting in the promotion of bone resorption in the context of periodontitis.

An anti–OC-STAMP-mAb reacting to the 28 aa sequence present in the C-terminal 180 peptides of mouse OC-STAMP was generated in this study to investigate the possible role of OC-STAMP in the pathogenic bone resorption of periodontitis. Yang et al. (4) had demonstrated that rabbit pAb that reacts with the C-terminal 180 peptides of mouse OC-STAMP could suppress the induction of RANKL-induced TRAP+ multinuclear OC from mouse RAW264.7 OCps in vitro. Furthermore, according to the putative 3-dimensional structure of OC-STAMP proposed by Witwicka et al. (3), the 28 aa sequence recognized by anti–OC-STAMP-mAb is positioned in the third extracellular loop among a total of 3 extracellular loops of OC-STAMP (3). Anti–OC-STAMP-mAb suppressed RANKL-mediated OC-genesis, especially the emergence of large multinuclear OC. An earlier study predicted that DC-STAMP functions in a manner similar to that of the GPCR superfamily (14). Because of the homology between OC-STAMP and DC-STAMP (3), it is plausible that OC-STAMP may also belong to the GPCR superfamily. In general, GPCR family molecules function as cell-signaling receptors for soluble ligand. Therefore, to explain the action elicited by xOC-STAMP-mAb, it is speculated that OC-STAMP could be a receptor for an unknown soluble ligand and that anti–OC-STAMP-mAb could then interrupt the ligation of putative soluble ligand with the third extracellular loop of OC-STAMP. Especially on the basis of results showing that anti–OC-STAMP-mAb could suppress in vitro cell fusion induced by the stimulation of OCps with RANKL alone (Figs. 3 and 5), it is plausible that such putative soluble ligand is produced by OCps in the in vitro culture condition. It is further conceivable that the expression of putative ligand for OC-STAMP by OCps is up-regulated in the course of periodontitis but not in healthy bone tissue, thus becoming a potential novel molecular target for the development of a therapeutic regimen to inhibit periodontal bone loss.

Thus far, DC-STAMP and OC-STAMP are the only molecules shown to be expressed by OCps and foreign-body giant cells for their cell fusion (38), making their biologic properties of particular interest in the study field of bone biology. Indeed, several other cell surface molecules, such as meltrin-α, CD47, syncytin-1, and E-cadherin, have been described for their roles in OC fusion, but their expression and activities are not restricted to OCps or giant cells (38–42). For example, knockdown of OC-STAMP resulted in the inhibition of multinucleated OC formation and decreased expression of genes including transcription factor c-Jun, receptors RANK and c-Fms, TRAF6 signaling molecule, and cell-fusion–related molecule meltrin-α (43). CD47 and its counterreceptor MFR/SIRPα have been shown to be engaged in the fusion of OC as well as macrophage (44–46). It has been reported that RANKL-stimulated OCps induce CD47, which is engaged in cell fusion of small OCs (1, 39, 44). However, CD47-KO mice demonstrate osteopetrotic bone phenotype (46), indicating that CD47 plays a role in homeostatic bone remodeling; therefore, it is challenging to develop a therapeutic approach for bone lytic diseases by targeting CD47. On the other hand, ATP6V0d2, a proton pump expressed in the plasma membrane of ruffled border on OCs, is required for fusion of OCps (36, 47). In ATP6V0d2-KO mice, the fusion of OCps to form mature multinuclear OCs is severely attenuated in vitro (36). Interestingly, ATP6V0d2-KO mice also show increased systemic bone formation (36), suggesting that ATP6V0d2 is involved in homeostatic bone remodeling. Although the role of ATP6V0d2 in facilitating extracellular acidification during bone resorption is well demonstrated, the molecular mechanism underlying ATP6V0d2-mediated OC fusion remains elusive. NFATc1, a master gene for RANKL-induced OC-genesis, induces OC fusion in conjunction with up-regulated expressions of ATP6V0d2 and DC-STAMP (37). However, in the in vitro murine model of OC maturation, proresolution mediator resolvin E1 (RvE1) inhibited DC-STAMP expression, but not ATP6V0d2 or NFATc1, suggesting that ATP6V0d2 is not associated with DC-STAMP expression (48). In the present study, ATP6V0d2 expression in the mouse gingival tissue induced of periodontitis was significantly lower in OC-STAMP-KO mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 1), whereas anti–OC-STAMP-mAb reduced the expression of ATP6V0d2 in RANKL-stimulated OCps in vitro (data not shown), indicating that OC-STAMP may be associated with the up-regulation of ATP6V0d2 expression in OCs. While outside the scope of the present study, the full elucidation of cell fusion machinery and the roles played by different fusogens at the molecular level in the plasma membrane of OCps will be the subject of future study.

As supported by the current paradigm of bone biology, OC-genesis in physiologic homeostatic bone remodeling and pathogenic bone resorption is mediated by RANKL in the same pathway. However, because OC-STAMP-KO mice show no bone phenotype, the present study was predicated on the hypothesis that OC-STAMP must be engaged in pathogenic bone resorption in periodontitis. On the other hand, we reported that OCps in circulation are recruited to the wear debris–induced bone lytic lesion through a unique chemokine, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), locally produced in the lesion (23), as opposed to stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), which chemoattracts OCps in circulation to the healthy bone remodeling site (49). This study revealed that migration of CXCR4+ OCps in the circulation to either normal bone remodeling or pathogenic bone resorption sites is controlled by 2 different chemokines, MIF or SDF-1, respectively, suggesting that MIF mediates the recruitment of OCps toward pathogenic bone resorption lesion, whereas SDF-1 is engaged in the recruitment of OCps to the healthy homeostatic bone remodeling site (23). To our knowledge, OC-STAMP appears to be the OC fusion-regulatory molecule that is distinctively engaged in pathogenic bone resorption in periodontitis but not in homeostatic bone remodeling, which stands in contrast to DC-STAMP, which is engaged in both homeostatic and pathogenic bone remodeling by increasing cell fusion in a manner independent of OC-STAMP/CD9. When we combine the discovery of distinct migration of OCps to the pathogenic bone resorption site with this finding of pathogenic periodontal bone resorption mediated by an OC-STAMP/CD9 axis, more light is shed on the study field of inflammatory bone resorption disorders, including periodontitis.

It is true that some adjunct therapies for periodontal disease in humans are available, including antibiotics and low-level laser treatment for antimicrobial and antibiofilm approaches, respectively (50, 51). However, long-term use of antibiotics is known to develop antibiotic-resistant bacteria (52), while the laser may cause tissue damage (53). Furthermore, the antibiotics or laser do not directly act on OCs to inhibit the periodontal bone loss. In contrast to small-molecule drugs, including antibiotics, antibody drugs show several desirable characteristics for the therapies of chronic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis, based on higher specificity, longer half-life, less possibility of developing neutralizing antibody, and less chance of causing adverse effects, compared to conventional small-molecule–based drugs (54, 55). For these reasons, in the last couple of decades, trends in the drug market have completely shifted toward the development of mAb-based drugs (56). Although, the development of mAb to multispanning transmembrane protein including OC-STAMP is challenging (57), we were able to develop a functional mouse mAb that can neutralize the effect of mouse OC-STAMP. It is reported that patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving anti–TNF-α mAb (infliximab) had lower periodontal indices and TNF-α levels in their gingival crevicular fluid (58), suggesting that mAb drugs targeting TNF-α can penetrate into periodontitis lesion and suppress the inflammatory response in periodontitis. Thus, it is plausible that a mAb specific to OC-STAMP would lead to the novel anti–bone loss approach for periodontitis.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grants DE-018499, DE-019917, and T32 DE 007327-12, NIH National Institute on Aging Grant AG-053615, and a research grant from King Abdulaziz University. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- AC

alveolar bone crest

- ATP6V0d2

ATPase H+ transporting V0 subunit d2

- BM

bone marrow

- CEJ

cementoenamel junction

- DC-STAMP

dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein

- KO

knockout

- MIF

macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- OC

osteoclast

- OC-genesis

osteoclastogenesis

- OCp

osteoclast precursor cell

- OC-STAMP

osteoclast-stimulatory transmembrane protein

- OPG

osteoprotegerin

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- RANKL

receptor activator of NF-κB ligand

- SDF-1

stromal-derived factor 1

- TRAP

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T. Ishii, A. Ikeda, S. Shindo, K. Egashira, and T. Kawai designed research; T. Ishii, M. Ruiz-Torruella, A. Ikeda, S. Shindo, A. Movila, H. Mawardi, A. Albasam, K. Egashira, W. Wisitrasameewong, K. Yamamoto, and T. Kawai analyzed data and provided the interpretation of results; T. Ishii, M. Ruiz-Torruella, A. Ikeda, S. Shindo, A. Movila, H. Mawardi, A. Albasam, K. Egashira, and W. Wisitrasameewong performed research; T. Ishii and T. Kawai wrote the article; and T. Ishii, A. Movila, R. A. Kayal, A. A. Al-Dharrab, A. I. Mira, K. Sueishi, X. Han, M. A. Taubman, T. Miyamoto, and T. Kawai contributed to revising it critically.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xing L., Xiu Y., Boyce B. F. (2012) Osteoclast fusion and regulation by RANKL-dependent and independent factors. World J. Orthop. 3, 212–222 https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v3.i12.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yagi M., Miyamoto T., Sawatani Y., Iwamoto K., Hosogane N., Fujita N., Morita K., Ninomiya K., Suzuki T., Miyamoto K., Oike Y., Takeya M., Toyama Y., Suda T. (2005) DC-STAMP is essential for cell–cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Exp. Med. 202, 345–351 https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20050645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witwicka H., Hwang S. Y., Reyes-Gutierrez P., Jia H., Odgren P. E., Donahue L. R., Birnbaum M. J., Odgren P. R. (2015) Studies of OC-STAMP in osteoclast fusion: a new knockout mouse model, rescue of cell fusion, and transmembrane topology. PLoS One 10, e0128275 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang M., Birnbaum M. J., MacKay C. A., Mason-Savas A., Thompson B., Odgren P. R. (2008) Osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein (OC-STAMP), a novel protein induced by RANKL that promotes osteoclast differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 215, 497–505 https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.21331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyamoto H., Suzuki T., Miyauchi Y., Iwasaki R., Kobayashi T., Sato Y., Miyamoto K., Hoshi H., Hashimoto K., Yoshida S., Hao W., Mori T., Kanagawa H., Katsuyama E., Fujie A., Morioka H., Matsumoto M., Chiba K., Takeya M., Toyama Y., Miyamoto T. (2012) Osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein and dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein cooperatively modulate cell–cell fusion to form osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1289–1297 https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii M., Iwai K., Koike M., Ohshima S., Kudo-Tanaka E., Ishii T., Mima T., Katada Y., Miyatake K., Uchiyama Y., Saeki Y. (2006) RANKL-induced expression of tetraspanin CD9 in lipid raft membrane microdomain is essential for cell fusion during osteoclastogenesis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 965–976 https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.060308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi T., Kim H. J., Cho J. Y., Woo K. M., Ryoo H. M., Kim G. S., Baek J. H. (2006) Tetraspanin CD9 regulates osteoclastogenesis via regulation of p44/42 MAPK activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347, 178–184 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawai T., Matsuyama T., Hosokawa Y., Makihira S., Seki M., Karimbux N. Y., Goncalves R. B., Valverde P., Dibart S., Li Y. P., Miranda L. A., Ernst C. W., Izumi Y., Taubman M. A. (2006) B and T lymphocytes are the primary sources of RANKL in the bone resorptive lesion of periodontal disease. Am. J. Pathol. 169, 987–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wara-aswapati N., Surarit R., Chayasadom A., Boch J. A., Pitiphat W. (2007) RANKL upregulation associated with periodontitis and Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Periodontol. 78, 1062–1069 https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2007.060398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin Q., Cirelli J. A., Park C. H., Sugai J. V., Taba M., Jr., Kostenuik P. J., Giannobile W. V. (2007) RANKL inhibition through osteoprotegerin blocks bone loss in experimental periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 78, 1300–1308 https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2007.070073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietrich T., Garcia R. I. (2005) Associations between periodontal disease and systemic disease: evaluating the strength of the evidence. J. Periodontol. 76(11 Suppl), 2175–2184 https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wisitrasameewong W., Kajiya M., Movila A., Rittling S., Ishii T., Suzuki M., Matsuda S., Mazda Y., Torruella M. R., Azuma M. M., Egashira K., Freire M. O., Sasaki H., Wang C. Y., Han X., Taubman M. A., Kawai T. (2017) DC-STAMP is an osteoclast fusogen engaged in periodontal bone resorption. J. Dent. Res. 96, 685–693 https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034517690490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bisson-Boutelliez C., Miller N., Demarch D., Bene M. C. (2001) CD9 and HLA-DR expression by crevicular epithelial cells and polymorphonuclear neutrophils in periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 28, 650–656 https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028007650.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mensah K. A., Ritchlin C. T., Schwarz E. M. (2010) RANKL induces heterogeneous DC-STAMP(lo) and DC-STAMP(hi) osteoclast precursors of which the DC-STAMP(lo) precursors are the master fusogens. J. Cell. Physiol. 223, 76–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wisitrasameewong W., Kajiya M., Movila A., Rittling S., Ishii T., Suzuki M., Matsuda S., Matsuda Y., Torruella M. R., Azuma M. M., Egashira K., Freire M. O., Sasaki H., Wang C. Y., Han X., Taubman M. A., Kawai T. (2017) DC-STAMP is an osteoclast fusogen engaged in periodontal bone resorption. J. Dent. Res. 96, 685–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaji K., Kudo A. (2004) The mechanism of sperm–oocyte fusion in mammals. Reproduction 127, 423–429 https://doi.org/10.1530/rep.1.00163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tachibana I., Hemler M. E. (1999) Role of transmembrane 4 superfamily (TM4SF) proteins CD9 and CD81 in muscle cell fusion and myotube maintenance. J. Cell Biol. 146, 893–904 https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.146.4.893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaji K., Oda S., Miyazaki S., Kudo A. (2002) Infertility of CD9-deficient mouse eggs is reversed by mouse CD9, human CD9, or mouse CD81; polyadenylated mRNA injection developed for molecular analysis of sperm–egg fusion. Dev. Biol. 247, 327–334 https://doi.org/10.1006/dbio.2002.0694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaji K., Oda S., Shikano T., Ohnuki T., Uematsu Y., Sakagami J., Tada N., Miyazaki S., Kudo A. (2000) The gamete fusion process is defective in eggs of Cd9-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 24, 279–282 https://doi.org/10.1038/73502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwai K., Ishii M., Ohshima S., Miyatake K., Saeki Y. (2008) Abundant expression of tetraspanin CD9 in activated osteoclasts in ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis and in bone erosions of collagen-induced arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 28, 225–231 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-007-0424-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawai T., Ito H. O., Sakato N., Okada H. (1998) A novel approach for detecting an immunodominant antigen of Porphyromonas gingivalis in diagnosis of adult periodontitis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5, 11–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsuzawa H., Kawai T., Wilson M. E., Taubman M. A., Sugai M., Suginaka H. (1999) Cloning of the gene encoding the Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans serotype b OmpA-like outer membrane protein. Infect. Immun. 67, 942–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Movila A., Ishii T., Albassam A., Wisitrasameewong W., Howait M., Yamaguchi T., Ruiz-Torruella M., Bahammam L., Nishimura K., Van Dyke T., Kawai T. (2016) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) supports homing of osteoclast precursors to peripheral osteolytic lesions. J. Bone Miner. Res. 31, 1688–1700 https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuda S., Movila A., Suzuki M., Kajiya M., Wisitrasameewong W., Kayal R., Hirshfeld J., Al-Dharrab A., Savitri I. J., Mira A., Kurihara H., Taubman M. A., Kawai T. (2016) A novel method of sampling gingival crevicular fluid from a mouse model of periodontitis. J. Immunol. Methods 438, 21–25 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu X., Hu Y., Freire M., Yu P., Kawai T., Han X. (2018) Role of Toll-like receptor 2 in inflammation and alveolar bone loss in experimental peri-implantitis versus periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 53, 98–106 https://doi.org/10.1111/jre.12492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26.Hu Y., Yu P., Yu X., Hu X., Kawai T., Han X. (2017) IL-21/anti-Tim1/CD40 ligand promotes B10 activity in vitro and alleviates bone loss in experimental periodontitis in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863, 2149–2157 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu P., Hu Y., Liu Z., Kawai T., Taubman M. A., Li W., Han X. (2016) Local induction of B cell interleukin-10 competency alleviates inflammation and bone loss in ligature-induced experimental periodontitis in mice. Infect. Immun. 85, e00645-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridaura V. K., Faith J. J., Rey F. E., Cheng J., Duncan A. E., Kau A. L., Griffin N. W., Lombard V., Henrissat B., Bain J. R., Muehlbauer M. J., Ilkayeva O., Semenkovich C. F., Funai K., Hayashi D. K., Lyle B. J., Martini M. C., Ursell L. K., Clemente J. C., Van Treuren W., Walters W. A., Knight R., Newgard C. B., Heath A. C., Gordon J. I. (2013) Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science 341, 1241214 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1241214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellekilde M., Selfjord E., Larsen C. S., Jakesevic M., Rune I., Tranberg B., Vogensen F. K., Nielsen D. S., Bahl M. I., Licht T. R., Hansen A. K., Hansen C. H. (2014) Transfer of gut microbiota from lean and obese mice to antibiotic-treated mice. Sci. Rep. 4, 5922 https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell W. C. (1947) Biology of the dermestid beetle with reference to skull cleaning. J. Mammal. 28, 284–287 https://doi.org/10.2307/1375178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai T., Eisen-Lev R., Seki M., Eastcott J. W., Wilson M. E., Taubman M. A. (2000) Requirement of B7 costimulation for Th1-mediated inflammatory bone resorption in experimental periodontal disease. J. Immunol. 164, 2102–2109 https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin X., Han X., Kawai T., Taubman M. A. (2011) Antibody to receptor activator of NF-κB ligand ameliorates T cell–mediated periodontal bone resorption. Infect. Immun. 79, 911–917 https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00944-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawai T., Paster B. J., Komatsuzawa H., Ernst C. W., Goncalves R. B., Sasaki H., Ouhara K., Stashenko P. P., Sugai M., Taubman M. A. (2007) Cross-reactive adaptive immune response to oral commensal bacteria results in an induction of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL)-dependent periodontal bone resorption in a mouse model. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 22, 208–215 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oz H. S., Puleo D. A. (2011) Animal models for periodontal disease. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 754857 https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/754857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abe T., Hajishengallis G. (2013) Optimization of the ligature-induced periodontitis model in mice. J. Immunol. Methods 394, 49–54 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S. H., Rho J., Jeong D., Sul J. Y., Kim T., Kim N., Kang J. S., Miyamoto T., Suda T., Lee S. K., Pignolo R. J., Koczon-Jaremko B., Lorenzo J., Choi Y. (2006) v-ATPase V0 subunit d2–deficient mice exhibit impaired osteoclast fusion and increased bone formation. Nat. Med. 12, 1403–1409 https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim K., Lee S. H., Ha Kim J., Choi Y., Kim N. (2008) NFATc1 induces osteoclast fusion via up-regulation of Atp6v0d2 and the dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP). Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 176–185 https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2007-0237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyamoto H., Katsuyama E., Miyauchi Y., Hoshi H., Miyamoto K., Sato Y., Kobayashi T., Iwasaki R., Yoshida S., Mori T., Kanagawa H., Fujie A., Hao W., Morioka H., Matsumoto M., Toyama Y., Miyamoto T. (2012) An essential role for STAT6-STAT1 protein signaling in promoting macrophage cell–cell fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 32479–32484 https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.358226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Møller A. M., Delaissé J. M., Søe K. (2017) Osteoclast fusion: time-lapse reveals involvement of CD47 and syncytin-1 at different stages of nuclearity. J. Cell. Physiol. 232, 1396–1403 https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.25633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hobolt-Pedersen A. S., Delaissé J. M., Søe K. (2014) Osteoclast fusion is based on heterogeneity between fusion partners. Calcif. Tissue Int. 95, 73–82 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-014-9864-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fiorino C., Harrison R. E. (2016) E-cadherin is important for cell differentiation during osteoclastogenesis. Bone 86, 106–118 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abe E., Mocharla H., Yamate T., Taguchi Y., Manolagas S. C. (1999) Meltrin-alpha, a fusion protein involved in multinucleated giant cell and osteoclast formation. Calcif. Tissue Int. 64, 508–515 https://doi.org/10.1007/s002239900641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim M. H., Park M., Baek S. H., Kim H. J., Kim S. H. (2011) Molecules and signaling pathways involved in the expression of OC-STAMP during osteoclastogenesis. Amino Acids 40, 1447–1459 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-010-0755-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lundberg P., Koskinen C., Baldock P. A., Löthgren H., Stenberg A., Lerner U. H., Oldenborg P. A. (2007) Osteoclast formation is strongly reduced both in vivo and in vitro in the absence of CD47/SIRPalpha-interaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 352, 444–448 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saginario C., Sterling H., Beckers C., Kobayashi R., Solimena M., Ullu E., Vignery A. (1998) MFR, a putative receptor mediating the fusion of macrophages. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 6213–6223 https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.18.11.6213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koskinen C., Persson E., Baldock P., Stenberg Å., Boström I., Matozaki T., Oldenborg P. A., Lundberg P. (2013) Lack of CD47 impairs bone cell differentiation and results in an osteopenic phenotype in vivo due to impaired signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 29333–29344 https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.494591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu H., Xu G., Li Y. P. (2009) Atp6v0d2 is an essential component of the osteoclast-specific proton pump that mediates extracellular acidification in bone resorption. J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 871–885 https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.081239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu M., Van Dyke T. E., Gyurko R. (2013) Resolvin E1 regulates osteoclast fusion via DC-STAMP and NFATc1. FASEB J. 27, 3344–3353 https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.12-220228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu X., Huang Y., Collin-Osdoby P., Osdoby P. (2003) Stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1) recruits osteoclast precursors by inducing chemotaxis, matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) activity, and collagen transmigration. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 1404–1418 https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.8.1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ren C., McGrath C., Jin L., Zhang C., Yang Y. (2017) The effectiveness of low-level laser therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: a meta-analysis. J. Periodontal Res. 52, 8–20 https://doi.org/10.1111/jre.12361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cobb C. M. (2017) Lasers and the treatment of periodontitis: the essence and the noise. Periodontol. 2000 75, 205–295 https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaman S. B., Hussain M. A., Nye R., Mehta V., Mamun K. T., Hossain N. (2017) A review on antibiotic resistance: alarm bells are ringing. Cureus 9, e1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aimetti M. (2014) Nonsurgical periodontal treatment. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 9, 251–267 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leavy O. (2010) Therapeutic antibodies: past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 297 https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beck A., Wurch T., Bailly C., Corvaia N. (2010) Strategies and challenges for the next generation of therapeutic antibodies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 345–352 https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu J. K. (2014) The history of monoclonal antibody development—progress, remaining challenges and future innovations. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond.) 3, 113–116 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hutchings C. J., Koglin M., Marshall F. H. (2010) Therapeutic antibodies directed at G protein–coupled receptors. MAbs 2, 594–606 https://doi.org/10.4161/mabs.2.6.13420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mayer Y., Balbir-Gurman A., Machtei E. E. (2009) Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy and periodontal parameters in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Periodontol. 80, 1414–1420 https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2009.090015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.