Abstract

Purpose

Information is lacking on prescribing of preventative cardiovascular pharmacotherapies for patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) in the Asian region. This study examined the prescribing rate of these pharmacotherapies, comparing NSTEMI to STEMI, and variations across demographics and clinical factors within the NSTEMI group in the multi-ethnic Malaysian population.

Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of the Malaysian National Cardiovascular Disease Database-Acute Coronary Syndrome registry from year 2006 to 2013 (n = 30,873). On-discharge pharmacotherapies examined were aspirin, ADP-antagonists, statins, ACE-inhibitors, angiotensin-II-receptor blockers, and beta-blockers. Multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratio of receiving individual pharmacotherapies according to patients’ characteristics in NSTEMI patients (n = 11,390).

Results

Prescribing rates for cardiovascular pharmacotherapies had significantly increased especially for ADP-antagonists (76%) in NSTEMI patients. More than 85% were prescribed statins and antiplatelets but rates remained significantly lower compared to STEMI. Women and those over 65 years old were less likely to be prescribed these pharmacotherapies compared to men and younger NSTEMI patients. Chinese and Indians were more likely to receive selected pharmacotherapies compared to Malays (main ethnicity). Geographical variations were observed; East Malaysian (Malaysian Borneo) patients were less likely to receive these compared to Western region of Malaysian Peninsular. Underprescribing in patients with risk factors such as diabetes were observed with other co-morbidities influencing prescribing selectively.

Conclusion

This study uncovers demographic and clinical variations in cardiovascular pharmacotherapies prescribing for NSTEMI. Concerted efforts by policy makers, specialty societies, and physicians are required focusing on elderly, women, Malays, East Malaysians, and high-risk patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00228-018-2451-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Prescribing, Preventative cardiovascular, STEMI, NSTEMI, Inequality

Introduction

Antiplatelets, beta-adrenoceptor blockers (beta-blockers), ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin-II-receptor blockers (ARBs), and statins are recommended as secondary preventative cardiovascular (CV) pharmacotherapies in post- acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients by international clinical practice guidelines [1, 2]. Although similar therapies were indicated for both ST-elevation MI (STEMI) and non-STEMI (NSTEMI), under-prescribing in prescribing for NSTEMI patients were shown in Europe and USA [3–7] highlighting the need to examine prescribing trends in other parts of the world. Previous studies have also demonstrated variations in CV prescribing especially in women, the elderly and ethnic minorities and across geographical regions [8, 9]. However, clinical factors remained as primary determinants of prescribing. Thus, variations in prescribing for NSTEMI across different demographics needs to be explored alongside clinical factors to identify possible sources of inequalities for improvement of care.

Malaysia, a multi-ethnic, upper middle-income country in South-East Asia, provides a unique opportunity to study prescribing trends in this region of the world. Geographically, Malaysia is made up of two parts separated by the South China Sea; the Malaysian Peninsular (West Malaysia) and the East of Malaysia on the northern part of Borneo (Malaysian Borneo) [10]. The three main ethnicities are Malays (50%) followed by Chinese (23%) and Indians (7%) while the rest are indigenous natives and other non-citizens [11]. The ethnicities differ in terms of culture, religion and socioeconomic statuses where the Chinese had economic advantages while the Malays hold political power [12]. Malaysia has expanded taxation-based public healthcare delivery system to provide access to comprehensive and affordable services via government-run healthcare facilities [13, 14]. Parallel to this, there are fast-growing private hospitals and clinics that are mostly concentrated in urban areas [14]. There are also corporatized public entities, one example being the National Heart Institute, at the crossroad of both public and private sectors [15].

Despite embracing advances in management of cardiovascular (CV) disease, it remained the leading cause of mortality in Malaysia, accounting for 23% of all deaths [16]. However, little information is available on the prevalence of STEMI and NSTEMI [17]. An increase in the prescribing of evidence-based pharmacotherapies has been described for STEMI [18] while less is known on NSTEMI. In acute interventions of AMI, women [19] and elderly patients [20] were less likely to receive optimal management compared to men and younger patients while no significant variations across ethnicities were observed [21]. Regional variations have remained unexplored. Exploring regional variations alongside other demographic variations will allow identification of gaps in provision of equal services across the country [22].

This study was aimed to examine trends in the prescribing of on-discharge secondary preventative CV therapies for patients with AMI, comparing STEMI and NSTEMI in Malaysian population using the prospective National Cardiovascular Disease Database-Acute Coronary Syndrome (NCVD-ACS) registry. This study further focused on variations in prescribing for NSTEMI patients across age groups, gender, geographical regions, clinical risk factors and co-morbidities. This registry is part of the NCVD registry whereby 18 hospitals contributed data from patients with CV diseases from year 2006 till current. It is being sponsored by the National Heart Association of Malaysia (NHAM) and are continuously monitored to ensure quality. The registry included information on demographic information, CV diagnosis, co-morbidities, family history and in-hospital management and on-discharge medications. The details of the registry have been described in detail elsewhere [23]. This database is among the few in South East Asia and thus provided valuable information on CV disease in this region of the world.

Methodology

Study population

Patients with AMI (n = 30,873), both STEMI (n = 19,483) and NSTEMI (n = 11,390) were identified from the NCVD-ACS registry from year 2006 to year 2013. Variables extracted were gender, age, ethnicity, calendar year of visit, risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking status, family history of ischemic heart disease (IHD), previous history of IHD, and co-morbid conditions such as cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), chronic kidney disease (CKD) and chronic lung disease. On-discharge CV medications included were antiplatelets (aspirin and adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-antagonists), ACEIs or ARBs, beta-blockers, and statins.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentages. Univariate analysis was used to compare characteristics between STEMI and NSTEMI patients. Prescribing rate of each secondary preventative CV pharmacotherapies were calculated according to calendar years and linear test was used to examine changes over time. Prescribing variations across groups of interest in NSTEMI patients were examined using binary logistic regression adjusting for covariates and presented as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Covariates chosen were those shown to impact prescribing trend such as age group, gender [19], ethnicity [9], calendar year, geographical regions [22], presence of risk factors and presence of co-morbidities [1, 2]. For geographical region, the Western Peninsular was chosen as the reference as this region has the most tertiary centers for CV referrals in this country [24]. SPSS version 24 was used for statistical analyses (IBM SPSS Statistics, NY). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

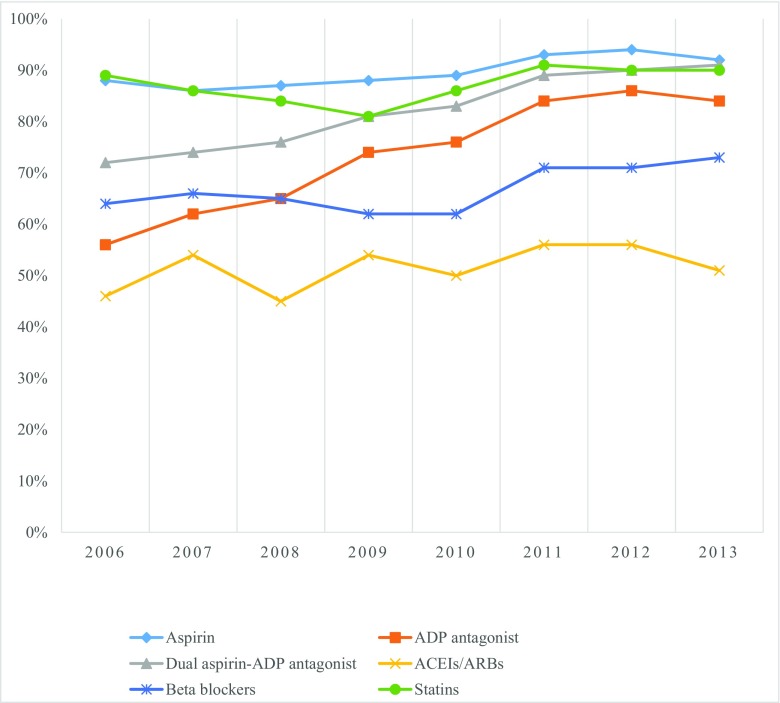

There were 30,873 patients who presented with AMI during this study period (81% males, 70% less than 65 years old and 53% Malays) (Table 1). Of those, 37% were NSTEMI. There were significant differences in demographics, CV risk factors and co-morbidities, comparing STEMI and NSTEMI (Table 1). Significantly lower proportion of NSTEMI patients received antiplatelets (p < 0.0001), beta-blockers (p = 0.001), and statins (p = 0.002) compared to STEMI (Supplementary Table 1). Significant increases in the prescribing of these agents (p < 0.0001) were observed over the study period (Fig. 1) with marked increase in the prescribing of ADP-antagonists. The prescribing of dual aspirin-ADP antagonists increased in parallel.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients who presented with AMI in the Malaysian NCVD-ACS between 2006 to 2013, comparing STEMI and STEMI

| Characteristics | Total n, (%) |

STEMI n, (%) |

NSTEMI n (%) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| < 65 | 21,016 (70%) | 14,463 (76%) | 6553 (60%) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 65 | 8976 (30%) | 4509 (24%) | 4467 (40%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 24,999 (81%) | 16,672 (86%) | 8327 (73%) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 5874 (19%) | 2811 (14%) | 3063 (27%) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Malay | 16,431 (53%) | 11,276 (58%) | 5155 (45%) | |

| Chinese | 6215 (20%) | 3454 (18%) | 2761 (24%) | < 0.001 |

| Indians | 6151 (20%) | 3270 (17%) | 2881 (25%) | |

| Others | 2076 (7%) | 1483 (8%) | 593 (5%) | |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Previous IHD | 4964 (19%) | 2126 (13%) | 2838 (30%) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 12,882 (48%) | 7065 (43%) | 5817 (56%) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 17,778 (65%) | 9706 (58%) | 8072 (76%) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 9637 (41%) | 4927 (35%) | 4710 (50%) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | 12,442 (54%) | 9609 (63%) | 2833 (36%) | < 0.001 |

| Family History | 3469 (11%) | 2195 (11%) | 1274 (11%) | < 0.001 |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1020 (4%) | 514 (3%) | 506 (5%) | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 222 (1%) | 55 (< 1%) | 167 (2%) | < 0.001 |

| CKD | 2112 (8%) | 646 (4%) | 1466 (15%) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 880 (3%) | 400 (2%) | 480 (5%) | < 0.001 |

| Regions | ||||

| Western Peninsular | 11,840 (39%) | 5837 (31%) | 6003 (53%) | < 0.001 |

| Eastern Peninsular | 4183 (14%) | 3143 (16%) | 1040 (9%) | < 0.001 |

| Northern Peninsular | 7084 (23%) | 4565 (24%) | 2519 (22%) | < 0.001 |

| Southern Peninsular | 4184 (14%) | 3625 (19%) | 559 (5%) | < 0.001 |

| East Malaysia | 3104 (10%) | 1931 (10%) | 1173 (10%) | < 0.001 |

Fig. 1.

Trends in the prescribing of on-discharge secondary preventative cardiovascular pharmacotherapies in patients with AMI in the Malaysian NCVD-ACS registry from 2006 to 2013

Older patients and women with NSTEMI were less likely to receive CV therapies (except beta-blockers) compared to younger patients and men (Table 2). Chinese and Indians were more likely to receive ADP-antagonists compared to Malays. Chinese were also more likely to receive statins while Indians were more likely to receive ACEIs/ARBs. There were significant regional differences, for example, patients in the Northern peninsular were more likely while those in East Malaysia were less likely to be prescribed these agents compared to Western peninsular. Patients with previous IHD or diabetes were less likely to be prescribed aspirin and statins compared to those without (Supplementary Table 2). Those with hypertension were more likely to receive ACEIs/ARBs and beta blockers. CKD patients were less likely to receive aspirin, ACEIs/ARBs and statins, those with cerebrovascular disease were less likely to be prescribed aspirin while those with chronic lung disease were less likely to receive beta-blockers.

Table 2.

Demographic variations in the prescribing of on-discharge secondary preventative cardiovascular pharmacotherapies for patients with NSTEMI in the Malaysian NCVD-ACS registry (2006–2013) presented as adjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI)

| Demographic characteristics | Aspirin | ADP-antagonists | ACEIs/ARBs | Beta blockers | Statins | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N, % | OR (95% CI) p value | N, % | OR (95% CI) p value | N, % | OR (95% CI) p value | N, % | OR (95% CI) p value | N, % | OR (95% CI) p value | |

| Age | ||||||||||

| < 65 | 5443 (91%) | Reference | 3300 (72%) | Reference | 3526 (55%) | Reference | 3995 (70%) | Reference | 5192 (88%) | Reference |

| ≥ 65 | 3438 (85%) | 0.54(0.47, 0.61) * | 2180 (70%) | 0.89(0.81, 0.99)* | 2114 (49%) | 0.79 (0.73,0.85) * | 2488(63%) | 0.75 (0.68, 0.81)* | 3412(85%) | 0.77(0.68, 0.86)* |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 6809 (90%) | Reference | 4202 (74%) | Reference | 4381 (54%) | Reference | 4970 (68%) | Reference | 6533 (87%) | Reference |

| Female | 2359 (85%) | 0.65(0.57, 0.74) * | 1450 (66%) | 0.70(0.63, 0.77) * | 1461 (50%) | 0.85 (0.78,0.92)* | 1726 (64%) | 0.84 (0.77, 0.93) ns | 2351 (86%) | 0.89(0.78, 1.01) ns |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Malay | 4148 (89%) | Reference | 2484 (69%) | Reference | 2647 (53%) | Reference | 3063 (68%) | Reference | 3991 (87%) | Reference |

| Chinese | 2220 (88%) | 0.95(0.81, 1.08) ns | 1373 (73%) | 1.15(1.01, 1.27) * | 1392 (52%) | 0.89 (0.74, 0.99) 0.002 | 1633 (67%) | 0.94(0.84, 1.09) ns | 2168 (87%) | 1.12(1.01, 1.28) * |

| Indian | 2359 (90%) | 1.05(0.94, 1.12) ns | 1544 (74%) | 1.25 (1.10, 1.36) * | 1574 (57%) | 1.14(1.01, 1.25) * | 1692 (66%) | 0.87(0.79, 0.98) 0.007 | 2311 (88%) | 1.20 (1.09, 1.32) * |

| Others | 441 (89%) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.15) ns | 251 (70%) | 1.04(0.92, 1.17) ns | 229 (39%) | 0.65 (0.49,0.79) * | 308 (64%) | 0.74(0.60, 0.87) 0.0001 | 414 (84%) | 0.88 (0.74,0.96) 0.002 |

| Regions | ||||||||||

| Western | 4894 | Reference | 3206 | Reference | 3032 | Reference | 3294 | Reference | 4653 | Reference |

| Peninsular | (89%) | (70%) | (53%) | (63%) | (87%) | |||||

| Eastern | 842 | 0.96 (0.85, 1.08) | 523 | 0.95(0.81, 1.14) | 664 | 1.45(1.32,1.58) | 729 | 1.57(1.45, 1.72) | 821 | 0.94(0.82,1.08) |

| Peninsular | (88%) | ns | (69%) | ns | (64%) | * | (76%) | * | (86%) | ns |

| Northern | 2177 | 1.07(0.94, 1.21) | 1205 | 1.14(1.01, 1.28) | 1539 | 1.34 (1.23, 1.42) | 1777 | 1.41 (1.32, 1.57) | 2124 | 1.12(1.01, 1.38) |

| Peninsular | (92%) | ns | (77%) | * | (61%) | * | (75%) | * | (89%) | 0.001 |

| Southern | 362 | 1.01(0.92, 1.15) | 187 | 1.24(1.12, 1.36) | 170 | 0.51 (0.38, 0.69) | 240 | 1.10 (1.02, 1.23) | 400 | 1.25(1.10, 1.41) |

| Peninsular | (91%) | ns | (81%) | * | (31%) | * | (63%) | 0.004 | (91%) | * |

| East Malaysia | 856 (83%) | 0.68 (0.58, 0.74) * | 523 (67%) | 0.82(0.70, 0.97) * | 416 (36%) | 0.69 (0.51, 0.78) * | 637 (63%) | 1.01(0.91, 1.20) ns | 845 (82%) | 0.81(0.74, 0.94) * |

ns not significant

*p < 0.0001

Discussion

There has been a significant increase in the prescribing of all CV therapies during the study period, with more than 85% of Malaysian patients with NSTEMI being prescribed aspirin and statins. The highest increase was observed with ADP-antagonists. NSTEMI patients were less likely to receive these medications compared to STEMI. Women and those ≥ 65 years old were less likely to receive CV therapies compared to men and younger NSTEMI patients. Significant variations were found across ethnicities and geographical regions. Risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension and co-morbidities such as cerebrovascular disease, CKD and chronic lung disease influenced CV prescribing for these patients.

Improvement in prescribing rate is similarly observed in other countries [7, 25, 26] and is believed to contribute to improvement in NSTEMI outcomes [27, 28]. Similar trend has been described for STEMI patients [18]. This may be due to increased adherence to clinical guidelines especially in hospitals who participated in NCVD registry. The Malaysian MOH together with NHAM are active in promoting evidence-based therapies and provided easy access to local clinical practice guidelines [29], both online and as small handbooks distributed throughout hospitals in Malaysia. Cost of medications may have influenced prescribing. Within each class of therapies are patented and generics drugs and efforts to increase generic formulations in Malaysia may improve availability of these drugs.

Like other population, women and the elderly were less likely to receive CV therapies compared to men and younger patients [8, 30]. Under-prescribing in the elderly has been described as “treatment-risk” paradox whereby patients become less likely to receive appropriate treatment with increasing age [31]. Financial consideration may play a role, especially in those who opt for non-generic drug [32]. Interestingly, Malaysians presented with MI at younger age compared to other developed countries [21]. Gender disparities may be explained by lower perceived risk of MI for women [33]. Malaysian women with MI were significantly older as well as having higher rates of co-morbidities compared to men [34]. The greatest CV treatment benefit for mortality reduction occurred in women between 65 and 84 years old [28]; hence, this group needs special attention. Reports of under-prescribing of medications in women are not specific to cardiovascular diseases and may require far-reaching measures in health care planning.

Chinese and Indians were more likely to receive CV therapies compared to Malays as the main ethnicity. Different ethnicities may exhibit different clinical profiles, for example, Chinese had highest rate of hypertension and hyperlipidemia while Indians had higher rate of diabetes [21]. Interestingly, both ethnicities have lower risk of cardiovascular mortality compared to Malays for NSTEMI [21]. Ethnic differences may reflect socioeconomic differences [9, 35]. Malays were generally concentrated in the poorer socioeconomic quintiles and hence considered to be socioeconomically disadvantaged [36]. Prescribing for other ethnic minorities was not significantly different to the main ethnicity. In contrast, Caucasians as the main race were more likely to receive medications compared to Hispanics, African Americans and Asian Americans in the USA [37]. The East Malaysia region, which is separated from the Malaysian peninsular, was less likely to receive these medications. Regional variations may be explained by characteristics of individuals and area-level factors such as population health, education levels, and ethnic composition [22] in addition to preference of hospitals and individual physicians [5]. There were a mix of ethnic minorities living in this region with lower socioeconomic status [12, 14, 36] and this may have influenced prescribing.

Those with NSTEMI were less likely to receive these medications compared to STEMI as physicians may favor more aggressive preventative therapies for STEMI [38]. Differences in demographic and clinical factors between these two groups may affect prescribing. Presence of clinical risk factors affected treatment preference for NSTEMI. For example, patients with hypertension were more likely to receive ACEIs/ARBs and beta-blockers. Surprisingly, those with previous history of IHD or diabetes were less likely to receive CV therapies compared to those without. This may be explained by ‘risk-treatment paradox’ where patients with higher risk of CVD were less likely to receive evidence based treatment [39]. Possible reason includes gaps in the evidence whereby there was uncertainty about the risk: benefit ratio in patients at higher risk. There may be information gaps whereby additional information not captured in the database may explain possible confounding factors in clinical decisions [39]. Concerns about co-morbidities such as chronic lung disease and CKD influenced prescribing options. Local specialty society such as NHAM have a role in promoting and educating physicians, especially junior physicians on current evidences and best practice [40].

This study uncovered variations in prescribing of evidence-based pharmacotherapies in NSTEMI patients using national CV registry. Recommendations for improvement should include establishment of hospital-based approaches such as medication checklists [41]. Information technology should be integrated to support decision-making and allows in-hospital prescribing to be followed up at discharge [42]. Ideally, treatment plan should be communicated with primary care physicians for continuity of care. Malaysia have not embraced the one patient-one GP system [14]. However, these patients will be followed up at each hospital’s outpatient clinic. Regular audit activities should be undertaken to ensure clinical practices are in line with guidelines and identify inequalities within hospital [43]. The state plays a role in promoting equal standard of care and ensuring continuous access to all evidence-based pharmacotherapies [14]. More generic medicine with good efficacy should be introduced as alternative to expensive originals, even in patients who attended private centers for a more efficient use of health resources [44]. Training for more physicians in the cardiology specialty to be based in different state hospitals should also be considered. In 2014, the number of cardiologists practicing in private centers in Malaysia were 184, compared to only 35 cardiologists in the government sector [24]. Physicians in general exclusively work in either state/government hospitals or private practice [14] although a trend toward dual practice is emerging [15]. This unequal distribution of physicians may influence prescribing trends in the country.

Strength and limitations

This study utilized data from hospitals nationwide to represent unselected group of patients in a real-world setting. The inclusion of different spectrum of patients allows prescribing trends to be examined objectively. The database is well maintained, and training is provided regularly to ensure data quality. Some information is self-reported such as smoking status and past medical history and thus misclassification and under-reporting may occur. Information that measures socioeconomic status such as occupation and educational levels were not available. Ethnic minorities living in remote areas may have difficulty accessing health facilities and could have been under-represented. Participation of hospitals into this database is voluntary and thus there may be a selection bias and an overestimate of prescribing in the general Malaysian population. Many private hospitals did not participate in this registry and thus prescribing in this sector could not be determined.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the prescribing of secondary preventative cardiovascular therapies for patients with NSTEMI had demonstrated significant improvement. This study uncovered demographical and clinical variations in the prescribing of cardiovascular therapies and hence concerted efforts by policy makers, specialty societies and physicians are required to overcome inequalities. Target population should include women, the elderly, Malay ethnicity, East Malaysians, diabetes, and CKD patients.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 19 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all medical and non-medical personnel who have participated and contributed to the NCVD-AMI registry, National Heart Association Malaysia (NHAM), Ministry of Health (MOH), Ministry of Education (MOE) of Malaysia, and Clinical Research Centre (CRC) Malaysia.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This NCVD registry study was approved by the Medical Review & Ethics Committee (MREC), Ministry of Health Malaysia in 2007 (Approval Code: NMRR-07-20-250).

Informed consent

The MREC waived the need for informed consent for studies utilizing this registry.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00228-018-2451-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, Gencer B, Hasenfuss G, Kjeldsen K, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Mehilli J, Mukherjee D, Storey RF, Windecker S, Baumgartner H, Gaemperli O, Achenbach S, Agewall S, Badimon L, Baigent C, Bueno H, Bugiardini R, Carerj S, Casselman F, Cuisset T, Erol Ç, Fitzsimons D, Halle M, Hamm C, Hildick-Smith D, Huber K, Iliodromitis E, James S, Lewis BS, Lip GY, Piepoli MF, Richter D, Rosemann T, Sechtem U, Steg PG, Vrints C, Luis Zamorano J, Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267–315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balzi D, Di Bari M, Barchielli A, et al. Should we improve the management of NSTEMI? Results from the population-based "acute myocardial infarction in Florence 2" (AMI-Florence 2) registry. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8(8):725–733. doi: 10.1007/s11739-012-0817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dondo TB, Hall M, Timmis AD, Gilthorpe MS, Alabas OA, Batin PD, Deanfield JE, Hemingway H, Gale CP. Excess mortality and guideline-indicated care following non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;6:412–420. doi: 10.1177/2048872616647705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dondo TB, Hall M, Timmis AD, Yan AT, Batin PD, Oliver G, Alabas OA, Norman P, Deanfield JE, Bloor K, Hemingway H, Gale CP. Geographic variation in the treatment of non-ST-segment myocardial infarction in the English National Health Service: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011600. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makam RC, Erskine N, McManus DD, et al. Decade-long trends (2001 to 2011) in the use of evidence-based medical therapies at the time of hospital discharge for patients surviving acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(12):1792–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.08.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNamara RL, Chung SC, Jernberg T, et al. International comparisons of the management of patients with non-ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and the United States: the MINAP/NICOR, SWEDEHEART/RIKS-HIA, and ACTION registry-GWTG/NCDR registries. Intern J Cardiol. 2014;175(2):240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buja A, Boemo DG, Furlan P, Bertoncello C, Casale P, Baldovin T, Marcolongo A, Baldo V. Tackling inequalities: are secondary prevention therapies for reducing post-infarction mortality used without disparities? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(2):222–230. doi: 10.1177/2047487312462148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonel AF, Good CB, Mulgund J, Roe MT, Gibler WB, Smith SC Jr, Cohen MG, Pollack CV Jr, Ohman EM, Peterson ED, CRUSADE Investigators Racial variations in treatment and outcomes of black and white patients with high-risk non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from CRUSADE (can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress adverse outcomes with early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines?) Circulation. 2005;111(10):1225–1232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157732.03358.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Statistics Malaysia (2017) Malaysia @ a glance. Department of Statistics, Malaysia. https://www.dosm.gov.my/. Accessed Sept 6 2017

- 11.Department of Statistics M . Malaysia in figures 2017. Putrajaya: Department of Statistics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakravarty SP, Roslan A-H. Ethnic nationalism and income distribution in Malaysia. Eur J Dev Res. 2005;17(2):270–288. doi: 10.1080/09578810500130906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merican MI, Rohaizat Y, Haniza S. Developing the Malaysian health system to meet the challenges of the future. Med J Malaysia. 2004;59(1):84–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas S, Beh L, Nordin RB. Health care delivery in Malaysia: changes, challenges and champions. J Public Health Africa. 2011;2(2):e23. doi: 10.4081/jphia.2011.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Minh H, Pocock NS, Chaiyakunapruk N et al (2014) Progress toward universal health coverage in ASEAN. Glob Health Action 7. 10.3402/gha.v7.25856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Department of Statistics Malaysia (2016) Statistics on Causes of Death, Malaysia, 2014. https://www.dosm.gov.my. Accessed 6th Apr 2017

- 17.Ang CS, Chan KM. A review of coronary artery disease research in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2016;71(Suppl 1):42–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venkatason P, Zubairi YZ, Hafidz I, Ahmad WAW, Zuhdi AS. Trends in evidence-based treatment and mortality for ST elevation myocardial infarction in Malaysia from 2006 to 2013: time for real change. Ann Saudi Med. 2016;36(3):184–189. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2016.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu HT, Nordin R, Wan Ahmad WA, Lee CY, Zambahari R, Ismail O, Liew HB, Sim KH, NCVD Investigators Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome in a multiethnic asian population: results of the malaysian national cardiovascular disease database-acute coronary syndrome (NCVD-ACS) registry. Glob Heart. 2014;9(4):381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuhdi A, Ahmad W, Zaki R, Mariapun J, Ali RM, Sari NM, Ismail MD, Kui Hian S. Acute coronary syndrome in the elderly: the Malaysian National Cardiovascular Disease Database-Acute Coronary Syndrome registry. Singap Med J. 2016;57(4):191–197. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu HT, Nordin RB. Ethnic differences in the occurrence of acute coronary syndrome: results of the Malaysian National Cardiovascular Disease (NCVD) database registry (march 2006 - February 2010) BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan SG, Cunningham CM, Hanley GE. Individual and contextual determinants of regional variation in prescription drug use: an analysis of administrative data from British Columbia. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad WA, Ali RM, Khanom M, et al. The journey of Malaysian NCVD-PCI (National Cardiovascular Disease Database-Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) registry: a summary of three years report. Int J Cardiol. 2013;165(1):161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Heart Association of Malaysia, Ministry of Health Malaysia . Annual report of the NCVD-ACS registry 2011–2013. Kuala Lumpur: National Heart Association of Malaysia and Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Luca L, Olivari Z, Bolognese L, et al. A decade of changes in clinical characteristics and management of elderly patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction admitted in Italian cardiac care units. Open Heart. 2014;1(1):e000148. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puymirat E, Schiele F, Steg PG, Blanchard D, Isorni MA, Silvain J, Goldstein P, Guéret P, Mulak G, Berard L, Bataille V, Cattan S, Ferrières J, Simon T, Danchin N, FAST-MI investigators Determinants of improved one-year survival in non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients: insights from the French FAST-MI program over 15 years. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(1):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unal B, Sozmen K, Arik H, et al. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in Turkey between 1995 and 2008. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabir Z, Perry IJ, Critchley J, et al. Modelling coronary heart disease mortality declines in the Republic of Ireland, 1985-2006. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2462–2467. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health Malaysia, National Heart Association of Malaysia, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia (2011) Clinical Pratice Guideline Management of Unstable Angina/Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (UA /NSTEMI) Ministry of Health Putrajaya

- 30.Mathur R, Badrick E, Boomla K, Bremner S, Hull S, Robson J. Prescribing in general practice for people with coronary heart disease; equity by age, sex, ethnic group and deprivation. Ethn Health. 2011;16(2):107–123. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2010.540312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko DT, Mamdani M, Alter DA. Lipid-lowering therapy with statins in high-risk elderly patients: the treatment-risk paradox. JAMA. 2004;291(15):1864–1870. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho S, Lau SW, Tandon V, et al. Geriatric drug evaluation: where are we now and where should we be in the future? Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(10):937–940. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Hayes SN, Walsh BW, Fabunmi RP, Kwan J, Mills T, Simpson SL. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation. 2005;111(4):499–510. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154568.43333.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CY, Hairi NN, Wan Ahmad WA, Ismail O, Liew HB, Zambahari R, Ali RM, Fong AYY, Sim KH, for the N-PCII Are there gender differences in coronary artery disease? The Malaysian National Cardiovascular Disease Database—percutaneous coronary intervention (NCVD-PCI) registry. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hull S, Mathur R, Boomla K, Chowdhury TA, Dreyer G, Alazawi W, Robson J. Research into practice: understanding ethnic differences in healthcare usage and outcomes in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(629):653–655. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X683053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mariapun J, Hairi NN, Ng CW. Are the poor dying younger in Malaysia? An examination of the socioeconomic gradient in mortality. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0158685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leigh JA, Alvarez M, Rodriguez CJ. Ethnic minorities and coronary heart disease: an update and future directions. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2016;18(2):9. doi: 10.1007/s11883-016-0559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montalescot G, Dallongeville J, Van Belle E, et al. STEMI and NSTEMI: are they so different? 1 year outcomes in acute myocardial infarction as defined by the ESC/ACC definition (the OPERA registry) Eur Heart J. 2007;28(12):1409–1417. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motivala AA, Cannon CP, Srinivas VS, Dai D, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Bhatt DL, Fonarow GC. Changes in myocardial infarction guideline adherence as a function of patient risk: an end to paradoxical care? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(17):1760–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leape LL, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, et al. Adherence to practice guidelines: the role of specialty society guidelines. Am Heart J. 2003;145(1):19–26. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanguturi VK, Temin E, Yeh RW, Thompson RW, Rao SK, Mallick A, Cavallo E, Ferris TG, Wasfy JH. Clinical interventions to reduce preventable hospital readmission after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(5):600–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bates DW, Gawande AA. Improving safety with information technology. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2526–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du X, Patel A, Li X, et al. Treatment and outcomes of acute coronary syndromes in women: an analysis of a multicenter quality improvement Chinese study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;241:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gama H, Torre C, Guerreiro JP, Azevedo A, Costa S, Lunet N. Use of generic and essential medicines for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases in Portugal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):449. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2401-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 19 kb)