Abstract

Introduction

Breast cancer in young women tends to be more aggressive, but timely treatment may not be always available, particularly to those without health insurance. We aim to examine whether the dependent coverage expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA-DCE) implemented in 2010 was associated with changes in time to treatment among women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer.

Methods

A total of 7,176 patients diagnosed with early stage breast cancer in 2007–2009 (pre-ACA) and 2011–2013 (post-ACA) were identified from the National Cancer Database. A quasi-experimental design difference-in-differences (DD) approach was used, with patients aged 19–25 (targeted by the policy) considered as the intervention group, and patients aged 26–34 years (not affected by the policy) as the control group. Changes in the following treatment outcomes were examined: time from diagnosis to surgery, time from surgery to adjuvant chemotherapy, and time from adjuvant chemotherapy to radiation.

Results

Compared with the control group of patients aged 26–34, young patients aged 19–25 experienced a statistically nonsignificant decrease of 2.7 percentage points (95% CI [-1.2, 6.5]) in the uninsured rate. This did not translate into more reduction in delays to surgery (DD = 2.7 days, 95% CI [-3.2, 8.3]), chemotherapy (DD = -1.0 days, 95% CI [-7.2, 5.2]) or radiation (DD = 5.3 days, 95% CI [-15.6, 26.3]) in the younger cohort than the older cohort.

Conclusions and Relevance

No significant changes in time to treatment were found among young women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer after the implementation of the ACA-DCE. Future studies examining impacts of health care policy reform on breast cancer care are warranted to include patients from low-income families and to consider effects from Medicaid expansion.

Introduction

Although breast cancer rarely occurs at young age, it still is one of the most common cancers among young adults [1, 2]. Moreover, breast cancer diagnosed in women younger than 35 years tends to be more aggressive and carries a worse prognosis than in older adults [3]. While timely treatment is essential for optimized prognosis and survival of breast cancer, it is not always available to patients without adequate health insurance [4–6]. This may be particularly problematic for young adults, who historically had the highest uninsured rate in the US [7]. In September 2010, the dependent coverage expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA-DCE) went into effect, allowing young adults to be covered under their parents’ health plans until they turn 26 years old. ACA-DCE has increased insurance coverage among the target population of young adults aged 19–25 years [8], as well as among newly diagnosed cancer patients of that age [2, 9]. However, the impact of this policy on access to breast cancer treatment among young women is unknown. This study aimed to examine if there is any change in time to treatment after the implementation of the ACA-DCE among young women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer.

Methods

Patients

We used data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB), a nationwide hospital-based cancer registry jointly sponsored by the American Cancer Society and the American College of Surgeons, including approximately 70% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases in the U.S.[10] From the NCDB, we identified female patients aged 19–34 years old at the time of diagnosis with a first primary stage I, IIA, IIB or IIIA-T3N1M0 breast cancer in 2007–2009 and in 2011–2013. The year 2010 was excluded as a washout/phase-in period. A quasi-experimental design difference-in-differences (DD) approach was used, with patients aged 19–25 (targeted by the policy) considered as the “intervention” group, and patients aged 26–34 years (not affected by the policy) as the “control” group. Only early stage breast cancer patients were included in the study to focus on patients who received breast surgery as their first treatment, sometimes followed by adjuvant radiation and/or systemic therapy.

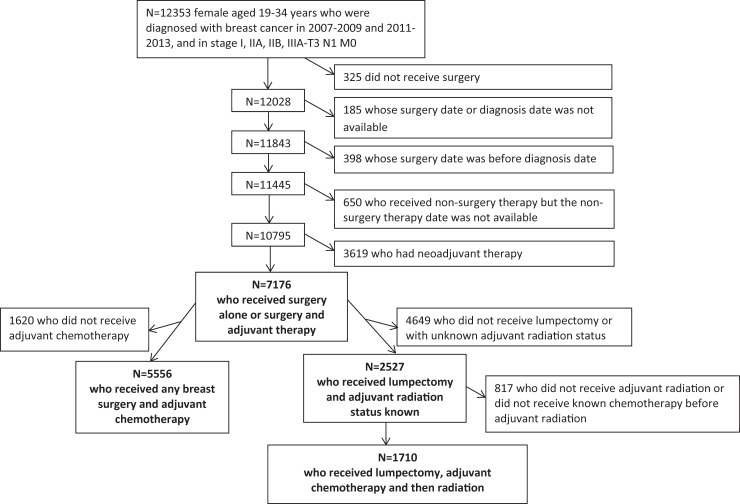

We excluded patients receiving no surgery, with autopsy pathology only, with local tumor destruction, or with surgery data missing (n = 325); any patient whose surgery date or diagnosis date was missing (n = 185), or with a diagnosis date after the surgery date (n = 398); patients whose radiation or systematic therapy date was missing if they received radiation or systematic therapy (n = 650); and patients who received neoadjuvant therapy (n = 3,619). Finally, a total of 7,176 female breast cancer patients were available for the analyses. Fig 1 provides a detailed inclusion/exclusion diagram.

Fig 1. Inclusion/Exclusion diagram.

The research was approved by the Morehouse University Institutional Review Board.

Outcomes

Our outcomes of interest include insurance coverage, time from diagnosis to the most definitive breast surgery, time from surgery to chemotherapy if adjuvant chemotherapy was received (N = 5556), receipt of adjuvant radiation therapy if lumpectomy was the definitive surgery (N = 2527), and time from adjuvant chemotherapy to radiation if lumpectomy and both adjuvant treatments were received (N = 1710). Those who received mastectomy were excluded in the radiation analyses because changing plastic surgery practices may have impacted the time to radiation substantially. Because previous research showed that a delay of more than 2 months from diagnosis to initial treatment [11] and a delay of 2–3 months in adjuvant therapy [5, 12–14] were associated with worse outcomes among breast cancer patients, we examined the proportion of patients who received surgery more than 2 months after the diagnosis and proportions of patients who received adjuvant therapy more than 2 months and 3 months.

Statistical analysis

We used a difference-in-difference (DD) approach to evaluate the impact of the ACA-DCE on insurance coverage and treatment, where changes from before to after the ACA-DCE (2007–2009 vs. 2011–2013) were calculated for the intervention group of patients aged 19–25 and for the control group of patients aged 26–34. Crude uninsured rate was calculated. DD estimates and p-values for treatment outcomes were calculated using multivariable linear probability models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, zip-code level education (percentage of residents in patient’s zip code without a high school diploma), region, stage, comorbidity score [15], and facility type. Surgery type (lumpectomy or mastectomy) and reconstruction status were also controlled in the analyses of time to surgery and time to adjuvant chemotherapy. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). Significance level was set at 0.05, and all statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

The study sample was composed of 6.0% patients in the intervention group and 94.0% in the control group. The majority of patients were non-Hispanic white (61.8%), privately-insured (78.4%), diagnosed at stage II (59.7%), and without comorbidity at the time of diagnosis (94.1%) (Table 1). After 2010, the uninsured rate decreased from 7.7% to 5.0% among patients aged 19–25 years, and unchanged at 4% among those aged 26–34 years, resulting a nonsignificant net decrease of 2.7 percentage points (ppt) (95% CI [-1.2, 6.5], P = 0.1749) among patients aged 19–25 years compared to those patients aged 26–34 years.

Table 1. Characteristics for young breast cancer patients, NCDB 2007–2013.

| Patients who received any breast surgery (N = 7176) |

Patients who received surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy (N = 5556) |

Patients who received lumpectomy (N = 2527) | Patients who received lumpectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation (N = 1710) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| 2007–2009 | 3466 (48.3) | 2717 (48.9) | 1402 (55.5) | 951 (55.6) |

| 2011–2013 | 3710 (51.7) | 2839 (51.1) | 1125 (44.5) | 759 (44.4) |

| Age group | ||||

| 19–25 years | 431 (6.0) | 312 (5.6) | 158 (6.3) | 99 (5.8) |

| 26–34 years | 6745 (94.0) | 5244 (94.4) | 2369 (93.7) | 1611 (94.2) |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 4433 (61.8) | 3453 (62.1) | 1436 (56.8) | 984 (57.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1204 (16.8) | 961 (17.3) | 512 (20.3) | 364 (21.3) |

| Hispanic | 620 (8.6) | 468 (8.4) | 223 (8.8) | 138 (8.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 569 (7.9) | 393 (7.1) | 229 (9.1) | 137 (8.0) |

| Unknown | 350 (4.9) | 281 (5.1) | 127 (5.0) | 87 (5.1) |

| Percentage of zip-code residents with no high school diploma | ||||

| <14% | 2731 (38.1) | 2099 (37.8) | 951 (37.6) | 643 (37.6) |

| 14–19.9% | 1544 (21.5) | 1195 (21.5) | 541 (21.4) | 371 (21.7) |

| 20–28.9% | 1558 (21.7) | 1229 (22.1) | 546 (21.6) | 379 (22.2 |

| 29% + | 1075 (15.0) | 821 (14.8) | 399 (15.8) | 261 (15.3) |

| Unknown | 268 (3.7) | 212 (3.8) | 90 (3.6) | 56 (3.3) |

| Primary payer | ||||

| Uninsured | 293 (4.1) | 217 (3.9) | 118 (4.7) | 77 (4.5) |

| Medicaid | 1015 (14.1) | 833 (15.0) | 359 (14.2) | 238 (13.9) |

| Medicare | 117 (1.6) | 87 (1.6) | 49 (1.9) | 31 (1.8) |

| Government | 19 (0.3) | 11 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) |

| Private | 5628 (78.4) | 4341 (78.1) | 1960 (77.6) | 1344 (78.6) |

| Unknown | 104 (1.5) | 67 (1.2) | 37 (1.5) | 18 (1.1) |

| Region | ||||

| South | 2722 (37.9) | 2125 (38.2) | 882 (34.9) | 611 (35.7) |

| Northeast | 1499 (20.9) | 1129 (20.3) | 571 (22.6) | 394 (23.0) |

| Midwest | 1801 (25.1) | 1458 (26.2) | 632 (25.0) | 449 (26.3) |

| West | 1118 (15.6) | 821 (14.8) | 429 (17.0) | 249 (14.6) |

| Unknown | 36 (0.5) | 23 (0.4) | 13 (0.5) | 5 (1.2) |

| Comorbidity score* | ||||

| 0 | 6754 (94.1) | 5227 (94.1) | 2402 (95.1) | 1623 (94.9) |

| 1 + | 422 (5.9) | 329 (5.9) | 125 (4.9) | 87 (5.1) |

| Stage | ||||

| I | 2691 (37.5) | 1659 (29.9) | 1099 (43.5) | 614 (35.9) |

| II | 4282 (59.7) | 3713 (66.8) | 1402 (55.5) | 1075 (62.9) |

| III | 203 (2.8) | 184 (3.3) | 26 (1.0) | 21 (1.2) |

| Facility type | ||||

| Community cancer program | 599 (8.4) | 457 (8.2) | 253 (10.0) | 171 (10.0) |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 2993 (41.7) | 2335 (42.0) | 1102 (43.6) | 751 (43.9) |

| Teach/research | 1740 (24.2) | 1341 (24.1) | 551 (21.8) | 374 (20.6) |

| NCI program/network | 1022 (14.2) | 774 (13.9) | 352 (13.9) | 220 (12.9) |

| Community network programs | 801 (11.2) | 631 (11.4) | 257 (10.2) | 185 (10.8) |

| Other & unknown | 21 (0.3) | 18 (0.3) | 12 (0.5) | 9 (0.5) |

Numbers in the table are: sample N (%).

* Modified weighted Charlson Deyo Score with cancer excluded from the construction of the score.

Between 2007–2009 and 2011–2013, the time from diagnosis to the most definitive breast surgery increased by several days both in patients aged 19–26 years and in those aged 26–34 years, with no significant difference in the change between the two groups (DD = 2.6 days, 95% CI [-3.2, 8.3], P = 0.3785) (Table 2). Similarly, we did not find a difference between the age groups in the change of the proportion of patients who received surgery later than 2 months after diagnosis (DD = -0.5 ppt, 95% CI [-7.2, 6.1], P = 0.8773). Similarly, among patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, the time to chemotherapy after definitive surgery did not change in either group, with no difference in the change between the groups (DD = -1.0 days, 95% CI [-7.2, 5.2], P = 0.7530). Among patients who received lumpectomy, no significant difference in the change was observed in receipt of adjuvant radiation therapy (DD = -3.2 ppt, 95% CI [-14.6, 8.2], P = 0.5835) nor in time from adjuvant chemotherapy to radiation therapy (DD = 5.3 days, 95% CI [-15.6, 26.3], P = 0.6173) between the groups.

Table 2. Difference-in-differences analysis for receipt and time to treatment among young breast cancer patients, NCDB 2007–2013.

| 19–25 years | 26–34 years | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment outcome | 2007–09 | 2011–13 | Difference and CI | 2007–09 | 2011–13 | Difference and CI | DD and CI | P-value |

| For patients who received any breast surgery (N = 7176) * | ||||||||

| N | 209 | 222 | 3257 | 3488 | ||||

| Days from diagnosis to the most definitive breast surgery | 41.7 | 46.7 | 5.0 (-0.5, 10.6) | 42.2 | 44.6 | 2.5 (1.0, 3.9) | 2.6 (-3.2, 8.3) | 0.3785 |

| > 60 days in receiving the most definitive surgery (%) | 22.0 | 22.7 | 0.7 (-5.7, 7.1) | 20.6 | 21.8 | 1.2 (-0.4, 2.9) | -0.5 (-7.1, 6.1) | 0.8773 |

| For patients who received any breast surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy* (N = 5556) | ||||||||

| N | 156 | 156 | 2561 | 2683 | ||||

| Days from breast surgery to adjuvant chemotherapy | 46.1 | 45.9 | -0.2 (-6.3, 5.9) | 46.1 | 46.9 | 0.8 (-0.7, 2.3) | -1.0 (-7.2, 5.2) | 0.7530 |

| > 60 days in receiving adjuvant chemotherapy (%) | 19.0 | 19.8 | 0.8 (-7.0, 8.6) | 21.9 | 22.2 | 0.3 (-1.6, 2.3) | 0.5 (-7.5, 8.4) | 0.9081 |

| > 90 days in receiving adjuvant chemotherapy (%) | 4.8 | 5.2 | 0.4 (-3.8, 4.7) | 6.0 | 4.7 | -1.3 (-2.4, -0.3) | 1.8 (-2.6, 6.1) | 0.4272 |

| For patients who received lumpectomy (breast conserving surgery) # (N = 2527) | ||||||||

| N | 90 | 68 | 1312 | 1057 | ||||

| Receipt adjuvant radiation (%) | 89.2 | 88.2 | -1.0 (-12.0, 10.0) | 87.2 | 89.4 | 2.2 (-0.7, 5.0) | -3.2 (-14.6, 8.2) | 0.5835 |

| For patients who received lumpectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation # (N = 1710) | ||||||||

| N | 59 | 40 | 892 | 719 | ||||

| Days from adjuvant chemotherapy to radiation | 144.2 | 153.3 | 9.0 (-11.3, 29.4) | 138.7 | 142.4 | 3.7 (-1.3, 8.7) | 5.34 (-15.6, 26.3) | 0.6173 |

| > 60 days in receiving radiation (%) | 95.6 | 95.9 | 0.3 (-5.9, 6.5) | 92.7 | 94.5 | 1.8 (0.3, 3.4) | -1.5 (-7.9, 4.8) | 0.6376 |

| > 90 days in receiving radiation (%) | 91.2 | 95.3 | 4.1 (-8.8, 17.0) | 81.2 | 86.6 | 5.4 (2.3, 8.6) | -1.3 (-14.6, 11.9) | 0.8438 |

CI = 95% confidence interval; DD = difference-in-differences. P-values are for DD.

* Models were adjusted for surgery type (lumpectomy or mastectomy), reconstruction status, age, race/ethnicity, education, region, stage, comorbidity score and facility type.

# Models were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, zip-code level education, region, stage, comorbidity score and facility type.

Discussion

We examined changes in insurance coverage and receipt of treatment among young women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer following the ACA dependent expansion insurance coverage using the NCDB from 2007–2013. We found a nonsignificant net decrease of 2.7 ppt in uninsured rate among patients aged 19–25 years relative to those patients aged 26–34 year following the ACA, which was comparable to the findings of two previous studies on young adult cancer patients using population-based cancer registry data [2, 9], where a net decrease in uninsured rate of 3.1 ppt and 2.0 ppt rate were found respectively. We did not find any significant differences in either age group or between the age groups in pre- to post- ACA changes in receipt of treatment or treatment delays including time from diagnosis to surgery, time from surgery to adjuvant chemotherapy, receipt of adjuvant radiation after lumpectomy, and time from adjuvant chemotherapy to radiation.

Although NCDB captures 70% of new cancer cases nationwide each year, breast cancer is rare among young adults, especially among the ACA-DCE extended parental insurance eligibility-targeted population of individuals with age 19–25 years old. Thus, a relatively small sample size limits the conclusiveness of our results. Also, the majority of beneficiaries of the extended parental insurance eligibility clause in the ACA-DCE, whose parents are covered by employer-sponsored or self-purchased private insurance, were likely from families that were relatively well-off financially [16]. For such patients, insurance coverage may not be the major barrier to access to treatment. Instead, increased use of different imaging modalities and delays introduced by genetic testing and frequent second opinions [17] might be more common sources of delay in socioeconomically advantaged patients. Young patients from low-income families may likely have benefited more from Medicaid expansion, another component of the ACA that was implemented in 2014 in the states that opted to expand Medicaid eligibility. Future studies exploring time to breast cancer treatment among young adults should consider the impact of Medicaid expansion along with the ACA-DCE.

Limitations of our study include relatively short follow-up time since the ACA-DCE, which is especially important given that there is inevitably a time lag between a policy implementation and ultimate impact on care; limited generalizability given that our sample was from Commission-on-Cancer accredited hospitals instead of a population-based sample; lack of information on other factors that may have impacted treatment delays over this period, such as increasing adoption of genomic assays and Oncotype Dx test; and unavailability of parents’ socioeconomic status to control for in the analyses.

Conclusions

In summary, this study found no statistically significant changes in time to breast cancer treatment among women 19–25 years old compared to slightly older women after the implementation of the ACA-DCE. Moving forward, studies examining the impact of the ACA on breast cancer care are warranted to include more patients from low-income families and to take Medicaid expansion into account.

Data Availability

The data we used in this study, National Cancer Database, is third party data from the American College of Surgeons. The data are available to researchers from the American Cancer Society or any Commission-on-Cancer-accredited cancer programs. Data access request can be made following the instructions on https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb. The authors confirm they did not have any special access privileges to these data.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Narrative Review of the Current Status and a View of the Future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(5):495–501. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4689 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han X, Zang Xiong K, Kramer MR, Jemal A. The Affordable Care Act and Cancer Stage at Diagnosis Among Young Adults. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(9). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw058 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, Ries L, editors. Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, including SEER incidence and survival: 1975–2000 Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER, Beck JR, Ross E, Wong YN, et al. Time to Surgery and Breast Cancer Survival in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(3):330–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4508 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4788555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chavez-MacGregor M, Clarke CA, Lichtensztajn DY, Giordano SH. Delayed Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Among Patients With Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(3):322–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3856 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith EC, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Delay in surgical treatment and survival after breast cancer diagnosis in young women by race/ethnicity. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(6):516–23. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1680 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer Bethesda, MD: 2006.

- 8.Sommers BD, Buchmueller T, Decker SL, Carey C, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act has led to significant gains in health insurance and access to care for young adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):165–74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0552 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsons HM, Schmidt S, Tenner LL, Bang H, Keegan TH. Early impact of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on insurance among young adults with cancer: Analysis of the dependent insurance provision. Cancer. 2016;122(11):1766–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29982 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4873374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Surgeons. National Cancer Database. Accessed April 27, 2017 at https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb [cited 2017 April 27].

- 11.McLaughlin JM, Anderson RT, Ferketich AK, Seiber EE, Balkrishnan R, Paskett ED. Effect on survival of longer intervals between confirmed diagnosis and treatment initiation among low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(36):4493–500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.39.7695 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3518728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagliato Dde M, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lei X, Theriault RL, Giordano SH, Valero V, et al. Clinical impact of delaying initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(8):735–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.7693 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3940536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebert-Croteau N, Freeman CR, Latreille J, Brisson J. Delay in adjuvant radiation treatment and outcomes of breast cancer—a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;74(1):77–94. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, Barbera L, Brouwers M, Browman G, Mackillop WJ. Does delay in starting treatment affect the outcomes of radiotherapy? A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(3):555–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.171 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–51. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han X, Zhu S, Jemal A. Characteristics of Young Adults Enrolled Through the Affordable Care Act-Dependent Coverage Expansion. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(6):648–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.027 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liederbach E, Sisco M, Wang C, Pesce C, Sharpe S, Winchester DJ, et al. Wait times for breast surgical operations, 2003–2011: a report from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(3):899–907. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4086-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data we used in this study, National Cancer Database, is third party data from the American College of Surgeons. The data are available to researchers from the American Cancer Society or any Commission-on-Cancer-accredited cancer programs. Data access request can be made following the instructions on https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb. The authors confirm they did not have any special access privileges to these data.