Abstract

Objective

To describe clinical issues related to bone health in patients with celiac disease (CD) and to provide guidance on monitoring bone health in these patients.

Sources of information

A PubMed search was conducted to review literature relevant to CD and bone health, including guidelines published by professional gastroenterological organizations.

Main message

Bone health can be negatively affected in both adults and children with CD owing to the inflammatory process and malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D. Most adults with symptomatic CD at diagnosis have low bone mass. Bone mineral density should be tested at diagnosis and at follow-up, especially in adult patients. Vitamin D levels should be measured at diagnosis and annually until they are normal. In addition to a strict gluten-free diet, supplementation with calcium and vitamin D should be provided and weight-bearing exercises encouraged.

Conclusion

Bone health can be adversely affected in patients with CD. These patients require adequate calcium and vitamin D supplementation, as well as monitoring of vitamin D levels and bone mineral density with regular follow-up to help prevent osteoporosis and fractures.

Case description

A previously healthy 39-year-old woman presented with chronic diarrhea, bloating, fatigue, and weight loss of 3 kg. Physical examination findings were unremarkable. Investigations revealed iron deficiency anemia. Her immunoglobulin A tissue transglutaminase (tTG) antibody level was elevated at greater than 250 U/mL (normal level is < 15 U/mL). Her serum calcium level was normal and her vitamin D level was 16.4 nmol/L (normal level is ≥ 50 nmol/L). She was referred to a gastroenterologist and intestinal biopsy results revealed total villous atrophy confirming celiac disease (CD). Her bone mineral density (BMD) was reduced, with a T-score of −2.9 SD. She was started on calcium (1000 mg) and vitamin D (2000 IU) supplements daily. A dietitian provided instructions for a strict gluten-free diet (GFD) and calcium-rich foods. At the 6-month follow-up, she was adherent to the diet and her symptoms had resolved. At the 1-year follow-up, she was well with negative tTG antibody and normal vitamin D levels. She was advised to return after a year for follow-up and BMD testing.

Celiac disease is a chronic disorder in which gluten (a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley) damages the small intestinal mucosa by an autoimmune mechanism in genetically susceptible individuals.1 It affects about 1% of the population. While some patients have a clinical picture of malabsorption dominated by diarrhea and weight loss (classical CD), others present with extraintestinal features including osteoporosis and consequently increased risk of fractures.2 The diagnosis of CD is based on well established criteria of positive serologic test results and abnormal small intestinal histology results.3 Dermatitis herpetiformis, “CD of the skin,” is characterized as a chronic itchy rash and most cases display villous atrophy, similar to CD.

The treatment of CD is a strict lifelong adherence to a GFD. Patients require regular follow-up to assess dietary compliance and monitoring for nutritional complications including bone disease and development of other autoimmune disorders such as thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes. A survey of Canadian gastroenterologists revealed that about a quarter of them do not provide long-term follow-up care routinely to patients with CD after diagnosis and most (86%) expect this to be done by the patient’s primary care physician.4 Therefore, family physicians have an important role in long-term monitoring of these patients including assessing their bone health.

Sources of information

A PubMed search was conducted (up to March 2017) to review literature relevant to CD and bone problems including guidelines by professional gastroenterological organizations. Search terms included celiac disease, osteopenia, osteoporosis, fracture, bone mineral density, and treatment. Information regarding recommendations for calcium and vitamin D intake is from Health Canada and the US Department of Agriculture.

Main message

Bone health in adults with CD.

Celiac disease affects bone structure. This manifests as low BMD and early onset of osteoporosis and osteomalacia, even in those without intestinal complaints.5 Multiple mechanisms could contribute to bone loss in CD.6–9 Calcium malabsorption and resulting hypocalcemia might directly lead to osteopenia or osteoporosis. Low serum calcium levels precipitate a compensatory release of parathyroid hormone (secondary hyperparathyroidism) that stimulates osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. While serum calcium levels might increase with this compensatory effect, osteoclast stimulation leads to an alteration in bone microstructure. Another contributor to low BMD is the direct stimulatory effect of proinflammatory cytokines (tumour necrosis factor α, interleukins 1 and 6) on osteoclast activity. There might also be decreased secretion of osteoprotegerin with resultant increase in osteoclast activation. Furthermore, CD has been associated with alterations in sex hormones in women due to periods of amenorrhea or early menopause, as well as in men due to a reversible androgen resistance. These alterations might contribute to osteoporosis. Vitamin D enhances calcium and phosphate absorption from the small intestine, providing an optimal environment for bone mineralization. Its malabsorption in CD can result in osteomalacia. It is important to recognize vitamin D deficiency because BMD can be improved with adequate supplementation

The prevalence of osteopenia or osteoporosis measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry among patients with CD is reported to be as high as 38% to 72% at diagnosis, and decreases by 50% during follow-up in adult patients after adherence to a strict GFD.5,10 The risk of low BMD among adults with newly diagnosed CD is higher with increased age, lower body mass index, and more years after menopause.10 Furthermore, low BMD is more common in classical and untreated CD but can be present in asymptomatic individuals with CD.11 Conversely, a 4-fold increase in the prevalence of CD has been found in patients with osteoporosis.12 Recent studies using high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography demonstrate microarchitecture deterioration in the trabecular region of peripheral bones of premenopausal women with CD compared with those of similar age without CD.13,14

Low BMD likely leads to increased risk of fractures. Studies evaluating the risk of fracture in patients with CD are heterogeneous in design and controversial in results. A meta-analysis confirmed an almost 2-fold increase in risk of fractures in patients with CD.15,16 Some studies suggest that the risk of fractures is more pronounced in patients with CD who have gastrointestinal symptoms (chronic diarrhea or malabsorption) compared with those diagnosed because of CD-associated conditions and with minimal symptoms.17,18

After starting a GFD, systemic inflammation decreases, intestinal mucosa heals progressively, and nutrient absorption recovers. Consequently, bone resorption decreases as calcium and vitamin D remineralize the matrix.5 This process has been confirmed in several studies, including some from Canada, showing an improvement in bone mineralization after starting a GFD,19–21 as well as a decrease in fracture risk.18 Increased levels of parathyroid hormone, osteocalcin, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, and tTG antibody, and decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels have been proposed as markers of bone disease and poor response to a GFD in follow-up.19

Recommendations for BMD testing and treatment in adults.

Based on the above evidence, the Canadian statement for bone health in CD recommends that adults with malabsorption have their BMD tested at diagnosis.22 Correction of malabsorption of calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D should be ensured.22–27 At the time of diagnosis, counseling needs to be provided by a dietitian with expertise in GFDs and in the nutrition required to restore bone health. The recommended daily intake of calcium and vitamin D are listed in Tables 1 and 2,28 respectively. Intake of these nutrients should be optimized using dietary sources, particularly dairy products, whenever possible (Tables 3 and 4).28,29 Also, to help improve bone density and strength, patients should be encouraged to participate in weight-bearing exercises, limit alcohol intake, and avoid cigarette smoking.

Table 1.

Recommended daily intake of calcium

| POPULATION | RECOMMENDED DIETARY ALLOWANCE OF CALCIUM PER DAY, mg | TOLERABLE UPPER INTAKE LEVEL OF CALCIUM PER DAY, mg |

|---|---|---|

| Infants, mo | ||

| • 0–6 | 200 | 1000 |

| • 7–12 | 260 | 1500 |

| Children, y | ||

| • 1–3 | 700 | 2500 |

| • 4–8 | 1000 | 2500 |

| • 9–18 | 1300 | 3000 |

| Adults, y | ||

| • 19–50 | 1000 | 2500 |

| • Men 51–70 | 1000 | 2000 |

| • Women 51–70 | 1200 | 2000 |

| • > 70 | 1200 | 2000 |

| Pregnant and lactating women, y | ||

| • 14–18 | 1300 | 3000 |

| • 19–50 | 1000 | 2500 |

Data from Health Canada.28

Table 2.

Recommended daily intake of vitamin D

| POPULATION | RECOMMENDED DIETARY ALLOWANCE OF VITAMIN D PER DAY, IU (μg) | TOLERABLE UPPER INTAKE LEVEL OF VITAMIN D PER DAY, IU (μg) |

|---|---|---|

| Infants, mo | ||

| • 0–6 | 400 (10) | 1000 (25) |

| • 7–12 | 400 (10) | 1500 (38) |

| Children, y | ||

| • 1–3 | 600 (15) | 2500 (63) |

| • 4–8 | 600 (15) | 3000 (75) |

| • 9–18 | 600 (15) | 4000 (100) |

| Adults, y | ||

| • 19–70 | 600 (15) | 4000 (100) |

| • > 70 | 800 (20) | 4000 (100) |

| Pregnant and lactating women | 600 (15) | 4000 (100) |

Data from Health Canada.28

Table 3.

Food and beverage sources of calcium

| FOOD OR BEVERAGE ITEM | SERVING SIZE | CALCIUM, mg |

|---|---|---|

| Milk (skim) | 1 cup | 316 |

| Almond milk (calcium fortified)* | 1 cup | 330 |

| Mozzarella cheese (partly skimmed) | 2 oz | 443 |

| Cheddar cheese | 2 oz | 403 |

| Yogurt (plain, low fat) | 6 oz | 311 |

| Yogurt (Greek, plain, nonfat) | 6 oz | 187 |

| Soy beverage (calcium fortified)* | 1 cup | 330 |

| Orange juice (calcium fortified)* | 1 cup | 330 |

| Salmon (pink, canned with bones) | 3.5 oz | 281 |

| Tofu (regular, calcium fortified) | 0.5 cup | 434 |

| Kale (cooked) | 0.5 cup | 47 |

| White beans (cooked) | 1 cup | 161 |

| Almonds (whole, natural with skins) | 1 cup | 385 |

Table 4.

Food and beverage sources of vitamin D

| FOOD OR BEVERAGE ITEM | SERVING SIZE | VITAMIN D, IU |

|---|---|---|

| Cod liver oil* | 1 tbsp | 1360 |

| Salmon (sockeye, canned with bones) | 3.5 oz | 834 |

| Mackerel (cooked) | 2.5 oz | 219 |

| Milk (fortified with vitamin D) | 1 cup | 117 |

| Orange juice (fortified with vitamin D)† | 1 cup | 100 |

| Soy beverage (fortified with vitamin D)† | 1 cup | 90 |

| Almond milk (fortified with vitamin D)† | 1 cup | 90 |

| Margarine (fortified with vitamin D) | 1 tsp | 20 |

| Yogurt (fortified with vitamin D) | 6 oz | 88 |

| Tuna white (canned in water) | 2.5 oz | 60 |

| Egg (whole cooked) | 1 large | 44 |

Patients without malabsorption but who are at high risk of bone disease should also have BMD testing done at diagnosis.22 The risk factors for osteoporosis include perimenopause or menopause in women, age older than 50 years in men, smoking, low body mass index, history of fragility fracture, and high tTG antibody titres.

Although the evidence is not robust, it appears prudent to treat patients with subclinical or asymptomatic CD with a GFD including adequate calcium and vitamin D supplements. Testing of BMD should be performed after 1 year of treatment before deciding on further management.22

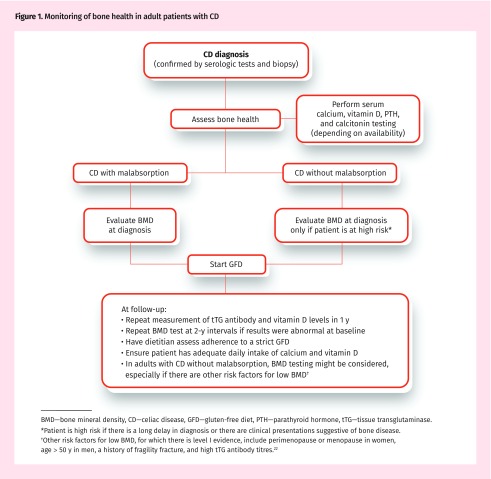

In those with osteoporosis or osteopenia at diagnosis or those who do not adhere to a GFD, it is recommended that BMD testing be repeated after 1 to 2 years following this diet with calcium or vitamin D supplementation. Adherence to a GFD ranges between 42% and 91%.30 Adherence to a GFD should be routinely assessed, preferably by a dietitian with expertise in this diet. If the results of BMD testing are normal at diagnosis, follow-up BMD testing might be considered 2 to 3 years after starting a GFD.22 Figure 122 summarizes these recommendations.

Figure 1.

Monitoring of bone health in adult patients with CD

BMD—bone mineral density, CD—celiac disease, GFD—gluten-free diet, PTH—parathyroid hormone, tTG—tissue transglutaminase.

*Patient is high risk if there is a long delay in diagnosis or there are clinical presentations suggestive of bone disease.

†Other risk factors for low BMD, for which there is level I evidence, include perimenopause or menopause in women, age > 50 y in men, a history of fragility fracture, and high tTG antibody titres.22

Bone health in children with CD.

In contrast to adults, children acquire their bone mass during growth. Canadian data demonstrates that the maximal time for bone accrual is the 4 years that surround peak linear growth.31 Therefore, optimal growth is a key factor for maximal bone accrual. Adolescents with CD will be at greater risk given this is the peak time for bone accrual.31 For this reason, early diagnosis of CD likely prevents long-term bone health concerns.

Like adults, both symptomatic and asymptomatic children with CD display decreased bone mass measured by BMD.22–25 However, when CD is diagnosed at a young age with a shorter duration of symptoms, the BMD recovers to normal values for age and size within 2 years, given adherence to a strict GFD with calcium and vitamin D supplementation.23 Therefore, routine BMD testing in children is not necessary.22 After diagnosis, adherence to the GFD and monitoring of growth and vitamin D status are adequate.31,32 Abnormalities of BMD are likely to occur with presentations associated with growth failure, severe malabsorption, prolonged delay in diagnosis, or clinical evidence of bone disease including bone pain, rickets, tetany, or fractures with minimal trauma. In such cases, a BMD test can be considered at diagnosis. When abnormalities are detected and treated, serial follow-up every 1 to 2 years should be conducted until the BMD normalizes. This is especially important for adolescents for whom recovery might be slower and dietary adherence more problematic. There are special considerations for interpretation of BMD in childhood, including monitoring age-related z scores, not T-scores.33 Healthy short children have smaller bones and an apparent lower bone mass, but no increased risk of fractures.33

Many Canadian children receive insufficient calcium and vitamin D owing to diets deficient in dairy products and inadequate sun exposure. At the time of CD diagnosis, it is recommended that the vitamin D level is measured and supplementation is provided if needed. Counseling about adequate dietary calcium and vitamin D intake (Tables 1 and 2)28 and weight-bearing exercises should be provided. Children and adolescents who do not comply with a strict GFD for 1 year should undergo BMD testing.

Recommendations for optimizing bone health in CD.

The evidence for management of low BMD and prevention of fractures in CD is limited. Strict adherence to a GFD seems to be the only effective treatment to improve BMD in adults and normalize BMD in children.22 This will decrease the risk of fractures. While there is no consensus on whether calcium and vitamin D supplementation should be prescribed to all patients with CD, it is prudent to ensure adequate calcium and vitamin D intake for all. The role of antiresorptive medications in reducing the risk of fractures in patients with CD also remains unclear. In the absence of strong evidence related specifically to CD, it is recommended that the guidelines from the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology, the American Gastroenterological Association, the Endocrine Society, the Scientific Advisory Council of Osteoporosis Canada, and other dietetic organizations be followed.22,34–38 Similarly, the use of hormone replacement therapy in perimenopausal women should be considered on a case-by-case basis, balancing potential benefits with risks.

If after 1 to 2 years of adhering to a GFD and including appropriate calcium and vitamin D supplementation the patient continues to show signs of osteoporosis, the addition of specific osteoactive treatments such as bisphosphonates or teriparatide should be considered.4 The evidence for these recommendations in CD is limited and appropriate studies are needed to address this issue.

Case resolution

Our patient had classical CD with diarrhea and iron deficiency anemia. Because she presented with malabsorption, BMD testing was done at baseline and results were abnormal. She responded well to a GFD and took calcium and vitamin D supplements. Her tTG antibody levels dropped to within the normal range. Given her low BMD at diagnosis, it would be reasonable to repeat testing in another 2 years to ensure that it has normalized. If this patient had had no added risk factors for osteoporosis and her presentation did not suggest severe malabsorption, BMD at diagnosis would not have been required. Many patients with CD will improve their BMD in the first year following a GFD.

Conclusion

Bone health can be adversely affected in both adults and children with CD. Bone mineral density testing at diagnosis should be considered, especially in adult patients. In addition to a strict GFD, adequate supplementation with calcium and vitamin D should be provided. The addition of specific osteoactive treatments such as bisphosphonates or teriparatide should be reserved for those with persistent osteoporosis despite adequate long-term calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Regular follow-up is important to monitor the bone health of patients with CD.

Editor’s key points

▸ Celiac disease (CD) is a chronic disorder that affects bone structure. It requires strict lifelong adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD), and long-term monitoring of patients with CD should include assessment of bone health.

▸ Bone health assessment in CD with malabsorption requires bone mineral density (BMD) testing at diagnosis. Correction of malabsorption of calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D should be ensured. At the time of diagnosis, patients should receive counseling on a GFD and on the nutrition required to restore bone health. Intake of calcium and vitamin D should be optimized using dietary sources, whenever possible. Patients should be encouraged to participate in weight-bearing exercises, limit alcohol intake, and avoid cigarette smoking.

▸ Evidence for management of low BMD and prevention of fractures in CD is limited. Strict adherence to a GFD seems to be the only effective treatment to improve BMD in adults with CD and decrease the risk of fractures.

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors contributed to the literature review and interpretation, and to preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de juin 2018 à la page e265.

References

- 1.Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, Biagi F, Fasano A, Green PH, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2013;62(1):43–52. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301346. Epub 2012 Feb 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinto-Sánchez MI, Bercik P, Verdu EF, Bai JC. Extraintestinal manifestations of celiac disease. Dig Dis. 2015;33(2):147–54. doi: 10.1159/000369541. Epub 2015 Apr 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F, Card TR, Ciacci C, Ciclitira PJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2014;63(8):1210–28. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578. Epub 2014 Jun 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silvester JA, Rashid M. Long-term management of patients with celiac disease: current practices of gastroenterologists in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(8):499–509. doi: 10.1155/2010/140289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanchetta MB, Longobardi V, Bai JC. Bone and celiac disease. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2016;14(2):43–8. doi: 10.1007/s11914-016-0304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corazza G, Di Stefano M, Mauriño E, Bai JC. Bones in coeliac disease: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19(3):453–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianchi ML, Bardella MT. Bone in celiac disease. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(12):1705–16. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0624-0. Epub 2008 Apr 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Stefano M, Mengoli C, Bergonzi M, Corazza GR. Bone mass and mineral metabolism alterations in adult celiac disease: pathophysiology and clinical approach. Nutrients. 2013;5(11):4786–99. doi: 10.3390/nu5114786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grace-Farfaglia P. Bones of contention: bone mineral density recovery in celiac disease—a systematic review. Nutrients. 2015;7(5):3347–69. doi: 10.3390/nu7053347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larussa T, Suraci E, Nazionale I, Abenavoli L, Imeneo M, Luzza F. Bone mineralization in celiac disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:198025. doi: 10.1155/2012/198025. Epub 2012 Apr 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazure R, Vazquez H, Gonzalez D, Mautalen C, Pedreira S, Boerr L, et al. Bone mineral affection in asymptomatic adult patients with celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(12):2130–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rios LP, Khan A, Sultan M, McAssey K, Fouda MA, Armstrong D. Approach to diagnosing celiac disease in patients with low bone mineral density or fragility fractures. Multi-disciplinary task force report. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:1055–61. (Eng), e441–8 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanchetta MB, Costa F, Longobardi V, Longarini G, Mazure RM, Moreno ML, et al. Significant bone microarchitecture impairment in premenopausal women with active celiac disease. Bone. 2015;76:149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.03.005. Epub 2015 Mar 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein EM, Rogers H, Leib A, McMahon DJ, Young P, Nishiyama K, et al. Abnormal skeletal strength and microarchitecture in women with celiac disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2347–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1392. Epub 2015 Apr 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olmos M, Antelo M, Vazquez H, Smecuol E, Mauriño E, Bai JC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies on the prevalence of fractures in coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.09.006. Epub 2007 Nov 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heikkilä K, Pearce J, Mäki M, Kaukinen K. Celiac disease and bone fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(1):25–34. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno ML, Vazquez H, Mazure R, Smecuol E, Niveloni S, Pedreira S, et al. Stratification of bone fracture risk in patients with celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(2):127–34. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(03)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sánchez MI, Mohaidle A, Baistrocchi A, Matoso D, Vázquez H, Gonzalez A, et al. Risk of fracture in celiac disease: gender, dietary compliance, or both? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(25):3035–42. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i25.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.González D, Mazure R, Mautalen C, Vazquez H, Bai JC. Body composition and bone mineral density in untreated and treated patients with celiac disease. Bone. 1995;16(2):231–4. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)00034-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferretti J, Mazure R, Tanoue P, Marino A, Cointry G, Vazquez H, et al. Analysis of the structure and strength of bones in celiac disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):382–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duerksen DR, Leslie WD. Longitudinal evaluation of bone mineral density and body composition in patients with positive celiac serology. J Clin Densitom. 2011;14(4):478–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2011.06.002. Epub 2011 Aug 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fouda MA, Khan AA, Sultan MS, Rios LP, McAssey K, Armstrong D. Evaluation and management of skeletal health in celiac disease: position statement. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(11):819–29. doi: 10.1155/2012/823648. Erratum in: Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2017:1323607. Epub 2017 Jul 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mora S, Barera G, Ricotti A, Weber G, Bianchi C, Chiumello G. Reversal of low bone density with a gluten-free diet in children and adolescents with celiac disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67(3):477–81. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scotta MS, Salvatorre S, Salvatoni A, De Amici M, Ghiringhelli D, Broggini M, et al. Bone mineralization and body composition in young patients with celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(8):1331–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kavak US, Yüce A, Koçak N, Demir H, Saltik IN, Gürakan F, et al. Bone mineral density in children with untreated and treated celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37(4):434–6. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludvigsson JF, Michaelsson K, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Coeliac disease and the risk of fractures - a general population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(3):273–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott EM, Gaywood I, Scott BB. Guidelines for osteoporosis in coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2000;46(Suppl 1):i1–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.suppl_1.I1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Health Canada . Vitamin D and calcium: updated dietary reference intakes. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2012. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/vitamins-minerals/vitamin-calcium-updated-dietary-reference-intakes-nutrition.html. Accessed 2018 Apr 24. [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Department of Agriculture [website] USDA Food Composition Databases. Beltsville, MD: United States Department of Agriculture; 2018. Available from: https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/. Accessed 2018 Apr 24. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall NJ, Rubin G, Charnock A. Systematic review: adherence to a gluten-free diet in adult patients with coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(4):315–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04053.x. Epub 2009 May 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey DA. The Saskatchewan Pediatric Bone Mineral Accrual Study: bone mineral acquisition during the growing years. Int J Sports Med. 1997;18(Suppl 3):S191–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blazina S, Bratanic N, Campa AS, Blagus R, Orel R. Bone mineral density and importance of strict gluten-free diet in children and adolescents with celiac disease. Bone. 2010;47(3):598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.06.008. Epub 2010 Jun 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wasserman H, O’Donnell JM, Gordon CM. Use of dual energy x-ray absorptiometry in pediatric patients. Bone. 2017;104:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.12.008. Epub 2016 Dec 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: guidelines on osteoporosis in gastrointestinal diseases Gastroenterology. 2003;124(3):791–4. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. Epub 2011 Jun 6. Erratum in: J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96(12):3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S, et al. 2010 Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 2010;182(17):1864–73. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100771. Epub 2010 Oct 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dietitians of Canada [website] Food sources of calcium. Toronto, ON: Dietitians of Canada; 2016. Available from: www.dietitians.ca/Your-Health/Nutrition-A-Z/Calcium/Food-Sources-of-Calcium.aspx. Accessed 2016 May 8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osteoporosis Canada . Nutrition. Health eating for healthy bones. Toronto, ON: Osteoporosis Canada; 2012. Available from: www.osteoporosis.ca/wp-content/uploads/OC_Nutrition_October_2012.pdf. Accessed 2018 Apr 23. [Google Scholar]