Abstract

Objective

To assess whether mothers and fathers have a higher long term risk of death, particularly from cardiovascular disease and cancer, after the mother has had pre-eclampsia.

Design

Population based cohort study of registry data.

Subjects

Mothers and fathers of all 626 272 births that were the mothers' first deliveries, recorded in the Norwegian medical birth registry from 1967 to 1992. Parents were divided into two cohorts based on whether the mother had pre-eclampsia during the pregnancy. Subjects were also stratified by whether the birth was term or preterm, given that pre-eclampsia might be more severe in preterm pregnancies.

Main outcome measures

Total mortality and mortality from cardiovascular causes, cancer, and stroke from 1967 to 1992, from data from the Norwegian registry of causes of death.

Results

Women who had pre-eclampsia had a 1.2-fold higher long term risk of death (95% confidence interval 1.02 to 1.37) than women who did not have pre-eclampsia. The risk in women with pre-eclampsia and a preterm delivery was 2.71-fold higher (1.99 to 3.68) than in women who did not have pre-eclampsia and whose pregnancies went to term. In particular, the risk of death from cardiovascular causes among women with pre-eclampsia and a preterm delivery was 8.12-fold higher (4.31 to 15.33). However, these women had a 0.36-fold (not significant) decreased risk of cancer. The long term risk of death was no higher among the fathers of the pre-eclamptic pregnancies than the fathers of pregnancies in which pre-eclampsia did not occur.

Conclusions

Genetic factors that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease may also be linked to pre-eclampsia. A possible genetic contribution from fathers to the risk of pre-eclampsia was not reflected in increased risks of death from cardiovascular causes or cancer among fathers.

What is already known on this topic

Maternal and fetal genes (including those inherited from the father) may contribute to pre-eclampsia, which occurs in 3-5% of pregnancies

One set of candidate genes for pre-eclampsia is the maternal genes for thrombophilia, which may increase the mother's risk of death from cardiovascular disease

What this study adds

Women who have pre-eclampsia during a pregnancy that ends in a preterm delivery have an eightfold higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease compared with women who do not have pre-eclampsia and whose pregnancy goes to term

Fathers of pregnancies in which pre-eclampsia occurred have no increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease

These results are compatible with maternal genes for thrombophilia having an effect on the risk of pre-eclampsia and of death from cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Pre-eclampsia, which is characterised by hypertension and proteinuria, occurs in 3-5% of pregnancies.1 The condition may be life threatening to the mother and the fetus if it is not properly managed, but it usually ends when the baby and placenta are delivered.2

The causes of pre-eclampsia are not well understood. A paradoxical preventive effect when the mother smokes has been established, even though the mechanism is unknown.3,4 Maternal and fetal genes, including paternal genes expressed in the fetus, probably also play a part.1,5 A high risk of recurrence of pre-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancies supports the role of an inherited susceptibility in the maternal genes. In a previous study in Norwegian women we reported a 12-fold increase in the risk of pre-eclampsia in a second pregnancy when the woman had had pre-eclampsia in the first pregnancy.6 A strong association of risks between sisters (odds ratio 2.2) and an increased occurrence of pre-eclampsia in daughters of mothers who had pre-eclampsia are further evidence of maternal genes for susceptibility.6,7

Paternal genes transmitted to the fetus also seem to be involved in pre-eclampsia. Our earlier study found that the risk of women having pre-eclampsia in their second pregnancy after having had pre-eclampsia in the first pregnancy was 12-fold higher when the fathers were the same in both pregnancies, compared with eightfold higher when the father was different.6 Furthermore, the risk of pre-eclampsia in any pregnancy was 1.8-fold higher when the father had previously fathered a pre-eclamptic pregnancy in another woman.6 Similar results have been reported in a study in California.8

Long term survival of mothers was addressed in 1976 by Chesley et al, who found no increased mortality in white women who had eclampsia in their first pregnancy.9 In 1981 Fisher et al expressed the view that the long term prognosis of cardiovascular disease in women with pre-eclampsia does not differ from that in the general population.10 On the other hand, Roberts and Cooper recently proposed common risk factors for pre-eclampsia and atherosclerosis.1 The set of genes that expresses thrombophilia is a candidate for susceptibility to pre-eclampsia.11 Women with complications in pregnancy associated with intervillous or spiral artery thrombosis and inadequate placental perfusion and with pre-eclampsia have more mutations of these genes.12 Genetic thrombophilia may, however, also increase a mother's risk of cardiovascular disease later in life. Specific fetal or paternal candidate genes have so far not been identified.

We followed up mothers and fathers of pre-eclamptic pregnancies to assess whether their risks of death from specific types of disease were higher than in parents of pregnancies without pre-eclampsia. Any such risk would shed light on factors involved in pre-eclampsia. Increased risk may, however, be associated with the secondary effects of pre-eclampsia. The evidence is increasing that mothers' exposure to hormones during pregnancy,13–15 particularly when the women have pre-eclampsia,16 affects their long term risk of having cancer. In our study we firstly compared the estimated total mortality of mothers and fathers of pre-eclamptic pregnancies with that of mothers and fathers of normal pregnancies. We then separately compared mortality from cardiovascular disease and from cancer in the same groups.

Materials and methods

Data on the cohorts were derived from the medical birth registry of Norway, which comprises all births in Norway since 1967 with more than 16 weeks of gestation (about 60 000 births a year), and from the registry of causes of death. Midwives and doctors must notify the birth registry of a range of personal and medical data.17 National identification numbers of child and mother are recorded for all births. The father's identification number is usually recorded but was missing in 13.9% of records of first births.

Most diagnoses of pre-eclampsia are notified as such to the medical birth registry. The notification form may also hold information on specific symptoms of pre-eclampsia, such as hypertension induced by pregnancy, proteinuria, and oedema. We defined cases of pre-eclampsia as all pregnancies with a specified diagnosis of pre-eclampsia and all pregnancies in which both hypertension induced by pregnancy and proteinuria were recorded. Birth weight was notified in 99% of birth records. Gestational age, based on the last menstruation, was recorded in more than 90% of births.

Mothers and fathers were divided into two groups according to whether the mother had pre-eclampsia during the pregnancy that resulted in her first delivery. Severe pre-eclampsia is likely to result in a preterm birth (less than 37 weeks' gestation). To identify pregnancies with severe pre-eclampsia we also stratified the cohorts by whether the delivery was term or preterm.

Using national identification numbers we matched records of parents in the medical birth registry with data from the cause of death registry, which is based on death certificates and specifies up to four diagnosed causes of death. We identified a total of 626 272 mothers whose first delivery was registered between 1967 and 1992. Mortality in this cohort of mothers and in the cohort of 539 316 men who were registered as fathers of these births was followed through to 1992. The length of follow up ranged from 0 to 25 years (median 13 years). As well as total mortality, we looked at mortality from cardiovascular causes, cancer, and stroke.

We defined cardiovascular mortality as all deaths in which the cause was registered as being related to the heart. This included codes 410 to 429 of ICD-8 and ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, 8th and 9th revisions). Cancer mortality included all deaths corresponding to codes 140 to 239.

We estimated survival curves representing total mortality, using the actuarial method, with censoring at the end of 1992. We used the log rank test to test for difference in total mortality. We compared mortality in mothers who had pre-eclampsia in their first pregnancy with mortality in other mothers by using the Cox proportional hazards model, adjusting for mother's age at delivery and year of birth of the baby. Mortality in the fathers was analysed similarly. We also used Cox models to compare mortality from specific causes. We used SPSS for Windows 6.0 to analyse data.

Results

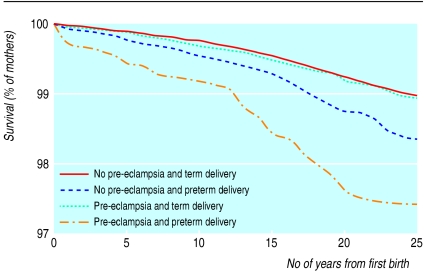

Altogether 4350 deaths occurred among the 626 272 mothers whose first delivery was registered between 1967 and 1992 (6.9 deaths per 1000). The proportions among mothers who had term pregnancies with pre-eclampsia and mothers who had preterm pregnancies with pre-eclampsia were 6.6 and 15.5 per 1000, respectively (table 1). The reduced survival in mothers who had preterm pregnancies with pre-eclampsia was consistent throughout the 25 years of follow up (figure). Among mothers who had a term delivery, survival was not lower when pre-eclampsia occurred during the pregnancy. Among mothers who did not have pre-eclampsia, survival was moderately reduced after preterm deliveries. After adjustment for maternal age and year of birth of the baby, Cox model analysis (with mothers who did not have pre-eclampsia and who had a term delivery as the reference group) showed a 1.56-fold higher risk of death (95% confidence interval 1.38 to 1.76) in women who had a preterm delivery but no pre-eclampsia and a 2.71-fold higher mortality in women who had a preterm delivery and pre-eclampsia (table 2). No increase in mortality was seen in women who had pre-eclampsia but whose pregnancy went to term.

Table 1.

Long term mortality of parents, according to whether mother had pre-eclampsia during pregnancy and gestational age of baby at birth, Norway, 1967-92

| Births between 1967 and 1992 | Gestational age of baby at birth | No of mothers | No of fathers | No (%) of pregnancies with unknown fathers | No of deaths (1967-92)

|

Deaths per 1000

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | ||||||

| No pre-eclampsia during pregnancy | ⩾ 37 weeks | 576 099 | 497 341 | 78 758 (13.7) | 3 882 | 8 491 | 6.7 | 17.1 | |

| 16-36 weeks | 26 018 | 20 861 | 5 157 (19.8) | 284 | 418 | 10.9 | 20.0 | ||

| Pre-eclampsia during pregnancy | ⩾ 37 weeks | 21 506 | 18 840 | 2 666 (12.4) | 143 | 313 | 6.6 | 16.6 | |

| 16-36 weeks | 2 649 | 2 274 | 375 (14.2) | 41 | 26 | 15.5 | 11.4 | ||

| All births | 626 272 | 539 316 | 86 956 (13.9) | 4 350 | 9 248 | 6.9 | 17.1 | ||

Table 2.

Long term mortality from specific causes among parents, according to whether mother had pre-eclampsia during pregnancy and gestational age of baby at birth, Norway, 1967-92. Values are relative hazard rates* (95% CIs)

| Births between 1967 and 1992 | Gestational age of baby at birth | All deaths (1967-92)

|

Deaths from cardiovascular causes

|

Deaths from stroke

|

Deaths from cancer

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | |||||

| No pre-eclampsia during pregnancy | ⩾ 37 weeks | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 16-36 weeks | 1.56 (1.38-1.76) | 1.10 (1.00-1.21) | 2.95 (2.12-4.11) | 0.97 (0.79-1.20) | 1.91 (1.26-2.91) | 1.39 (0.95-2.04) | 1.32 (1.10-1.58) | 1.08 (0.88-1.32) | ||||

| Pre-eclampsia during pregnancy | ⩾ 37 weeks | 1.04 (0.88-1.23) | 1.01 (0.90-1.13) | 1.65 (1.01-2.70) | 1.01 (0.81-1.27) | 0.98 (0.50-1.91) | 1.03 (0.64-1.68) | 0.90 (0.29-2.78) | 0.98 (0.77-1.23) | |||

| 16-36 weeks | 2.71 (1.99-3.68) | 0.75 (0.51-1.10) | 8.12 (4.31-15.33) | 1.03 (0.55-1.92) | 5.08 (2.09-12.35) | (no deaths) | 0.36 (0.12-1.11) | 0.66 (0.30-1.47) | ||||

Obtained from Cox regression, adjusted for mother's age at delivery and year of birth of baby.

The increased risk of death among women who had pre-eclampsia and a preterm delivery was more marked among women who died from cardiovascular causes: the risk in this group was 8.12-fold higher (4.31 to 15.33) than that in the reference group (women who died from cardiovascular causes and who had term pregnancies without pre-eclampsia). For cardiovascular causes, an increased risk was also shown in mothers who had pre-eclampsia and a term delivery (1.65-fold; 1.01 to 2.70). The increase was 2.95-fold (2.12 to 4.11) after a pregnancy without pre-eclampsia but that ended in a preterm delivery. Similar but weaker results were seen in mothers who died from stroke (table 2).

For cancer mortality, the risk was decreased (0.36-fold) in women who had pre-eclampsia and a preterm delivery. Although this reduction was not significant, it contrasted with a significant increase in risk (1.32-fold; 1.10 to 1.58) in women who did not have pre-eclampsia but did have a preterm delivery.

Altogether 9284 deaths occurred among the fathers (17.1 per 1000) (table 1). Whether the mother had pre-eclampsia had no significant effect on the long term survival of the fathers (P for difference=0.42). Overall mortality among the fathers was higher than that in the mothers partly because the mean age of the fathers was higher. No significantly increased risk of death from cardiovascular causes was seen among men who had fathered a pregnancy in which pre-eclampsia occurred. The reduction in cancer mortality (0.66-fold) among fathers of pregnancies in which pre-eclampsia occurred and that were preterm was less than that in mothers and was not significant.

Discussion

Our findings are consistent with but do not prove the hypothesis that the long term risk of death from cardiovascular causes is associated with a maternal genetic predisposition to pre-eclampsia. The association between mortality and pre-eclampsia may also reflect long term complications of the disease or a common effect of social or environmental conditions.

We found no evidence that a father's risk of death from cardiovascular causes was related to pre-eclampsia in the mother. Paternal genes in the fetus may increase the risk of pre-eclampsia in a particular pregnancy.6 Such genes are, however, probably not related to risk of cardiovascular disease.

A tendency of a reduced risk of death from cancer was seen in mothers who had pre-eclampsia. This is consistent with a lower prevalence of smoking among mothers who had pre-eclampsia.3,4 A reduced risk of death from cancer among fathers of pregnancies in which pre-eclampsia occurred might be related to the mother and father having similar smoking patterns. A protective mechanism related to reduced levels of oestrogen in cases of pre-eclampsia is also consistent with a reduced risk of death from cancer among mothers.16 Interestingly, this contrasted with an increased risk of death from cancer in mothers whose first pregnancy was preterm but who did not have pre-eclampsia.

Misclassification of outcome might have occurred, in that cardiovascular and cancer causes of death could have been overlooked in the death certificate. However, such misclassification would not be differential and would not bias the relative risk.

The prevalence of pre-eclampsia in first pregnancies, as measured by our methods, concurs with the prevalence found in most other studies and indicates that our measure of pre-eclampsia was reliable and accurate.1,18,19 We defined pre-eclampsia stringently by excluding pregnancies in which only hypertension induced by pregnancy or hypertension combined with oedema occurred and by including only mothers' first births.

Confounding might explain the strong association between pre-eclampsia and increased cardiovascular mortality in mothers. Smith et al found a negative association between weight at birth of babies and long term cardiovascular mortality of their mothers.20,21 Thus, the association with pre-eclampsia might also be an effect of birth weight, or mechanisms related to birth weight.19 In our data pre-eclampsia had an independent effect on cardiovascular mortality, even after adjustment for birth weight (a 2.59-fold higher risk in mothers who had preterm births and pre-eclampsia; P=0.005). Adjustment for birth weight could be overadjustment, because reduced birth weight would be an effect and a marker of more severe pre-eclampsia. In any case, there is no reason to consider birth weight as a confounder. On the other hand, the existence of other factors causing both pre-eclampsia and increased mortality cannot be further elucidated.

That cardiovascular mortality in women who had preterm deliveries but no pre-eclampsia was higher than in women who had a term delivery and pre-eclampsia justifies further speculation. Underreporting of pre-eclampsia in preterm deliveries would bias the effect of preterm deliveries towards higher relative risks. Alternatively, increased cardiovascular mortality could be due to more than one factor: in pre-eclampsia it may be related to genetic thrombophilia, and in preterm deliveries it may be related to other factors (smoking, for example, even though it is not generally agreed that smoking and preterm deliveries are related22). Increased cancer mortality (as well as increased cardiovascular and stroke mortality) is consistent with such a hypothesis. Furthermore, if smoking masks the symptoms of pre-eclampsia, a special reason for underreporting would exist that would provide further evidence of the role of genetic thrombophilia.4

One important limitation of this study is the incomplete follow up of the cohort. The maximum follow up was 26 years, and the median was about 13 years. Although our results apply only to relatively young women, the implications for prevention of pre-eclampsia and determination of its causes may still be important. With longer follow up the pattern of risks may become clearer but may also change. We followed parents from the mother's first delivery, partly for simplicity and partly because pre-eclampsia is more likely to occur in a mother's first pregnancy.2 It is possible that the risk of death in the long term changes with outcome in subsequent pregnancies.

Figure.

Long term survival of mothers after their first delivery, according to whether they had pre-eclampsia and gestational age of baby at birth (term=37 weeks or more)

Footnotes

Funding: Helse og Rehabilitering.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Roberts JM, Cooper DW. Pathogenesis and genetics of pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2001;357:53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins JR, de Swiet M. Blood-pressure measurement and classification in pregnancy. Lancet. 2001;357:131–135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcoux S, Brisson J, Fabia J. The effect of cigarette smoking on the risk of pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130:950–957. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cnattingius S, Mills JL, Yuen J, Eriksson O, Salonen H. The paradoxical effect of smoking in preeclamptic pregnancies: smoking reduces the incidence but increases the rates of perinatal mortality, abruption placentae, and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:156–161. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70455-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haig D. Genetic conflicts in human pregnancy. Q Rev Biol. 1993;68:495–532. doi: 10.1086/418300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lie RT, Rasmussen S, Brunborg H, Gjessing HK, Lie-Nielsen E, Irgens LM. Fetal and maternal contributions to risk of pre-eclampsia: population based study. BMJ. 1998;316:1343–1347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mogren I, Høgberg U, Winkvist A, Stenlund H. Familial occurrence of pre-eclampsia. Epidemiology. 1999;10:518–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li DK, Wi S. Changing paternity and the risk of pre-eclampsia/eclampsia in the subsequent pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:57–62. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesley LC, Annitto JE, Cosgrove RA. The remote prognosis of eclamptic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;124:446–459. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher KA, Luger A, Spargo BH, Lindheimer MD. Hypertension in pregnancy: clinical-pathological correlations and remote prognosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1981;60:267–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kupferminc MJ, Eldor A, Steinman N, Many A, Bar-Am A, Jaffa A, et al. Increased frequency of genetic thrombophilia in women with complications of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:9–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Groot CJ, Bloemenkamp KW, Duvekot EJ, Helmerhorst FM, Bertina RM, Van Der Meer F, et al. Preeclampsia and genetic risk factors for thrombosis: a case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:975–980. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albrektsen G, Heuch I, Tretli S, Kvåle G. Breast cancer incidence before age 55 in relation to parity and age at first and last births: a prospective study of one million Norwegian women. Epidemiology. 1994;5:604–611. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199411000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albrektsen G, Heuch I, Kvåle G. The short-term and long-term effect of a pregnancy on breast cancer risk: a prospective study of 802 457 parous Norwegian women. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:480–484. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albrektsen G, Heuch I, Kvåle G. Multiple births, sex of children and subsequent breast-cancer risk for the mothers: a prospective study in Norway. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:341–344. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Innes KE, Byers TE. Preeclampsia and breast cancer risk. Epidemiology. 1999;10:722–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irgens LM. The medical birth registry of Norway. Epidemiological research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:435–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Births in Norway through 30 years. Bergen: Medical Birth Registry of Norway; 1997. pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindheimer MD, Katz AI. Hypertension in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:675–680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509123131107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith GD, Harding S, Rosato M. Relation between infants' birth weight and mothers' mortality: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;320:839–840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7238.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith GD, Whitley E, Gissler M, Hemminki E. Birth dimensions of offspring, premature birth, and the mortality of mothers. Lancet. 2000;356:2066–2067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyrklund-Blomberg NB, Cnattingius S. Preterm birth and maternal smoking: risks related to gestational age and onset of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1051–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]