Abstract

Estrogens are neuroprotective, and studies suggest that they may mitigate the pathology and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in female models. However, central estrogen effects have not been examined in males in the context of AD. The purpose of this follow-up study was to assess the benefits of a brain-selective 17β-estradiol estrogen prodrug, 10β,17β-hydroxyestra-1,4-dien-3-one (DHED), also in the male APPswe/PS1dE9 double transgenic mouse model of the disease. After continuously exposing 6-month old animals to DHED for two months, their brains showed decreased amyloid precursor and amyloid-β protein levels. The DHED-treated APPswe/PS1dE9 double transgenic subjects also exhibited enhanced performance in a cognitive task, while 17β-estradiol treatment did not reach statistical significance. Taken together, data presented here suggest that DHED may also have therapeutic benefit in males and warrant further investigations to fully elucidate the potential of targeted estrogen therapy for a gender-independent treatment of early-stage AD.

Keywords: estradiol, brain-selective prodrug, Alzheimer’s disease, male double transgenic mice, learning

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by cognitive and neuronal dysfunctions associated with amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. AD affects men and women differently (Laws et al., 2016; Irvine et al., 2012). So far, there has not been clear explanation for the gender differences in AD, or in other central nervous system-related disorders (Musicco 2009; Carter et al., 2012; Zagni et al., 2016). Therefore, it is important to include both sexes in basic science studies, especially if preclinical drug candidates are evaluated in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases.

Due to the prevalence of AD in females (Lobo et al., 2000; Callahan et al., 2001; Irvine et al., 2012), most studies concentrate on the use of estrogen-deprived female animals owing to the logical correlation between loss of endogenous estrogens and increased incidence of neurodegeneration in women (Baum 2005). As such, only a few studies have been devoted to the potential beneficial effect of estrogens in males, especially in the context of AD (Rosario et al., 2010; Carroll and Rossario 2012). Estrogens have long been shown to be neuroprotective via a variety of mechanisms pertinent to the neuropathology of neurodegeneration, including AD (Lan et al., 2015; Davey 2017). Additionally, estrogens may also act as neuroprotective antioxidants (Prokai et al., 2003; Prokai–Tatrai et al., 2008 & 2013) to ameliorate some effects of oxidative stress-related injury and redox dysregulation that have been implicated in the initiation and/or progression of neurodegenerative diseases (von Bernhardi and Eugenin, 2012). In spite of evidence for neuroprotection, the use of the main human estrogen, 17β-estradiol (E2), in AD as a preventative or therapeutic agent is yet to be fully justified in clinical setting (Wharton et al., 2009; Correia et al., 2010).

While the rate of occurrence in men is lower than in women, genetic mutations, as in familial AD, also can increase the probability of developing AD in males (Bird 2008; Bekris et al., 2010). Particular genetic variants have been utilized in developing animal models to mimic pathology of AD. Others and our laboratory have been using the APPswe/PS1dE9 double transgenic AD model (abbreviated below as DTG), which possesses a chimeric mouse/human amyloid precursor protein (APP) Swedish gene (APP695SWE) and the human PS1 delta-E-9 (PS1dE9) gene (Heikkinen et al., 2004; Jankowsky et al., 2004; Tschiffely et al., 2016). This mouse model displays behavioral deficiencies at seven months of age (Reiserer et al., 2007) that correlate temporally with the appearance of plaques (Jankowsky et al., 2004) making it suitable to study early apperance of the disease.

Previously we have showed that treatment with 10β,17β-dihydroxyestra-1,4-dien-3-one (DHED), a brain-selective prodrug of E2 that produces the hormone only in the brain (Prokai et al., 2015, Merchenthaler et al., 2016), decreased Aβ levels in the brain of ovariectomized female DTG mice and, consequently, these animals had higher cognitive performance than the untreated control group (Tschiffely et al., 2016). This beneficial effect was similar to those treated with the parent E2. However, the distinguishing feature of chronic DHED administration was the lack of peripheral E2 formation, indicating therapeutic safety. As a continuation of this previous study, the present investigation focused on assessing the AD-therapeutic potential of DHED in males of the same DTG mouse model in terms of slowing down the progression of AD characteristics onset, including the reduction of Aβ formation and protecting against cognitive impairment. We hypothesized that administration of DHED would provide therapeutic benefit against early-stage AD mimicked by the selected animal model of the disease in a gender-independent fashion.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

17β-dihydroxyestra-1,4-diene-3-one (DHED) was synthesized from E2, as reported before (Prokai et al., 2015). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise stated.

Animals

Transgenic APPswe/PS1dE9 mice (obtained from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were bred and maintained through the laboratory of Dr. Rosemary Schuh (Veterans Affairs Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore, MD). At the age of 3–4 months, they were transferred from Dr. Schuh’s colony to the University of Maryland College Park according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved protocols. Mice were then bred at the University of Maryland and additional animals were transferred from the colony as needed for the duration of the study. The APPswe/PS1dE9 hemizygote genotype was maintained by crossing a female C57BL/6 mouse (The Jackson Laboratory) with a male APPswe/PS1dE9. Animals were bred on site and weaned at 21–25 days of age, tail snipped and genotyped at 30–35 days of age. They were group-housed by sex in an environmentally controlled animal facility on a 12/12 hour light/dark schedule. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All animal care and experimental procedures were conducted under the University of Maryland, College Park IACUC approved protocols. To minimize any confounding factor of estrogenic compounds in the diet, one week prior to initiating treatments all animals, including controls, were placed on a phytoestrogen free diet (AIN-93G, Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ, USA) to eliminate dietary estrogen sources. Age-matched males lacking AD pathology in our breeding colony (referred below as non-transgenic animals, NTG) were used as controls in experiments involving the DTG subjects. Accordingly, the following treatment groups were formed for the present study (with seven to nine animals assigned to each group): NTG-VEH, NTG-DHED, NTG-E2, DTG-VEH, DTG-DHED, DTG-E2, where VEH denotes propylene glycol vehicle only treatment.

Treatment schedule

As our murine model expresses behavioral deficits at 6–7 months of age correlating temporally with the appearance of amyloid plaques, the experimental design focused on evaluation at 8 months of age (Jankowsky et al., 2004; Reiserer et al., 2007). Additionally due to the early initiation of estrogen therapy required to obtain a beneficial outcome treatment, our study began at 6 months of age in APPswe/PS1dE9 male mice (Sherwin et al., 2005). Animals (5.5–6 months, N = 7–9) were treated with vehicle (propylene glycol), E2 (2 μg/day), or DHED (2 μg/day) via subcutaneously (s.c.) implanted Alzet osmotic minipumps (0.025μL/min, Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA) over the 8-week period of treatment. The concentration of the experimental agent (E2 or DHED) was 56 μg/mL. Pumps were replaced once, at the 4-week time point analogously to our recently reported studies (Prokai et al., 2015; Tschiffely et al., 2016). Briefly, testing started 24–48 h after finishing treatment with the experimental agents.

Radial arm water maze (RAWM) behavioral testing

A radial-arm water maze (Alamed et al., 2006) was used to measure cognitive deficits of the mice post-treatment period. Experimental set up was identical to that of previously reported (Tschiffely et al., 2016). On day 1 of training, twelve trials that alternated between a hidden and visible platform followed by three trials of all hidden platforms were done. On days 2 and 3, fifteen hidden platforms were used. Each mouse was assigned to the same goal arm throughout testing. The start arm changed for each trial and if the mouse did not locate the platform within 60 seconds, the mouse was gently directed to the platform and allowed to rest there for 10 seconds before being removed from the pool. A 60-second cutoff time was chosen to ensure endurance and stamina for the animals. An error was recorded as an entry via all four paws into an incorrect arm or the goal arm without successful location of the platform. An error score did not require that the animal swim to the back of the arm entirely before turning around. All animals were scored by the same observer blinded to the treatment schedule from a consistent site in the testing facility.

Tissue collection

Immediately following behavioral testing, animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The brain was immediately removed and half of each brain was flash frozen, then stored at –80°C until further processing via homogenization using 1 mL of homogenization buffer (consisting of 225 mM ultra-pure mannitol, 75 mM ultra-pure sucrose, 5 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, pH to 7.4) at 4˚C for biochemical and molecular analyses.

Western blot for APP

Proteins (25 μg) as determined by the standard Lowry method from forebrain homogenates were resolved using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 10% precast Bis-Tris gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to an Immobilon FL polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) using a Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (BioRad). Membranes were blocked for 60 min before exposure to primary antibodies against APP (6E10, Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA) and β-actin (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) overnight at 4˚C. Then membranes were exposed to secondary anti-mouse (6E10) and anti-rabbit (β-actin) IRdye antibodies and imaged using an Odyssey system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). Densitometry was performed using the Odyssey software (LI-COR) and measurements were expressed as ratio of APP to β-actin.

Aβ levels

Aβ(1-40) and Aβ(1-42) variants were quantified using commercially available ELISA kits from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY, USA). Briefly, standards provided by the company, and samples were measured using a monoclonal primary (rabbit) antibody specific for the N-terminus region of human Aβ(1-40) or Aβ(1-42). The bound primary antibody was detected by horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit antibody proportional to human Aβ in the sample. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using the Victor microplate reader (Wallac 1420, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Final concentration values of Aβ peptides were expressed as pg/mg protein.

Statistical analyses

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for APP and Aβ analyses using a 3x2 factorial design to include all treatments of NTG and DTG males (Box et al., 2005). Post hoc analysis was performed using the Tukey’s honestly significant differences (HSD) test to determine significant differences in treatment groups, both within NTG and DTG as well as to the treatment across NTG and DTG. Analyses of behavioral data were based on a method specific for the RAWM paradigm and Alzheimer’s transgenic mice (Morgan, 2009). We first performed repeated measures ANOVA to ascertain any main effect of treatment and behavioral trials. Post hoc means comparisons using Tukey’s HSD test were conducted to identify treatment group differences on specific trials or blocks for both NTG and DTG males. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. Effect sizes were estimated as partial eta squared (ηp2) and the standardized difference between two means (Cohen’s d) for ANOVA results (Brown, 2008) and pairwise comparisons (Cohen, 1988), respectively.

Results and discussion

We report here that DHED-treated DTG male mice showed benefits of lower levels of APP immunoreactivity and Aβ peptide levels in tandem with improved cognitive behavior. Throughout the study, we used age-matched NTG male animals not exhibiting AD pathology due to the absence of the APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenes as controls. Previously, DHED was shown to be a prodrug converting to E2 through reduction catalyzed by an NADPH-dependent short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase selectively in the brain (Prokai et al., 2015), and beneficial effects on APP and Aβ levels, as well as on cognitive behavior have been demonstrated in female AD transgenic mice treated with DHED (Tschiffely et al., 2016).

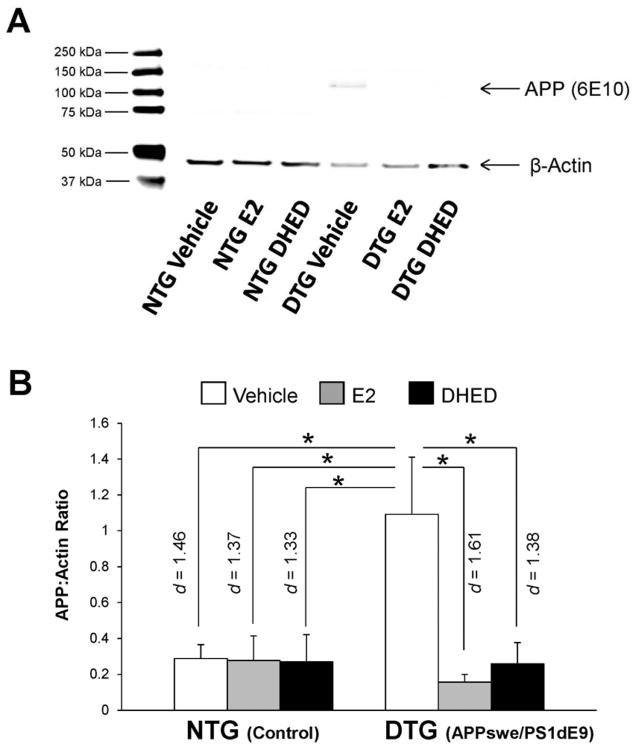

For APP immunoreactivity in the forebrain, we observed statistically significant main effects of treatment (F(2,35)=4.98; p=0.012; ηp2=0.222) and transgene ′ treatment interaction (F(2,35)=4.69; p=0.016; ηp2=0.211). A significantly higher expression of full length APP was obtained in the DTG-VEH group than in the NTG–VEH group (p = 0.014, d = 1.46), as shown in Figure 1. At the same time, no impact of estrogen was seen in NTG animals. However, treatments had significant effect in DTG animals: both the DTG-E2 (p = 0.007, d = 1.61) and the DTG-DHED groups (p = 0.020, d = 1.38) exhibited significantly lower APP immunoreactivity in the brain than the DTG-VEH group. Further, DTG-E2 and DTG-DHED groups did not differ significantly from each other or from those in the NTG groups.

Fig. 1. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) immunoreactivity in the forebrain of male NTG versus DTG mice.

Male control non-transgenic (NTG) and double-transgenic (DTG) mice were dosed with vehicle, estradiol (E2) or DHED; effects on APP immunoreactivity were compared. (A) Representative western blot of APP and β-actin bands. APP bands shown at ~106 kDa and β-actin shown at ~47kDa. (B) Data expressed as APP:β-actin ratios ± SEM (N = 6–8/group) based on densitometry. APP (6E10) levels were decreased in the E2- and DHED-treated groups compared to vehicle-treated DTG animals. *p<0.05 by post hoc Tukey’s HSD test; effect sizes indicated by Cohen’s d values.

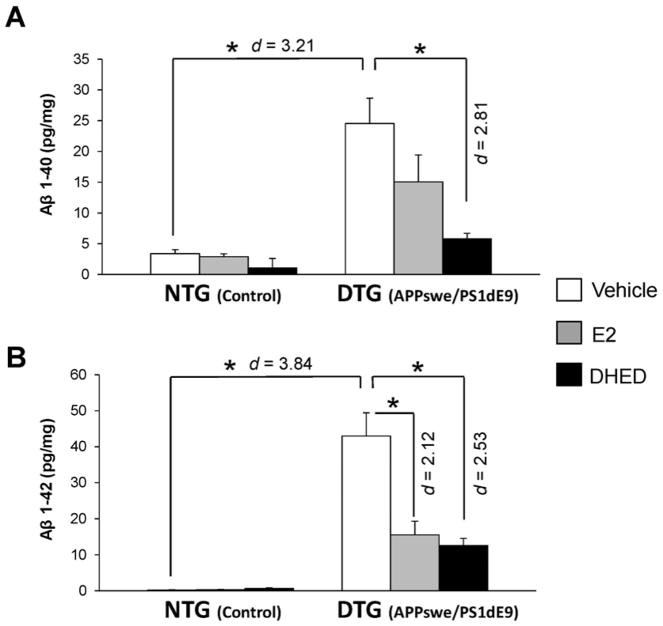

Statistically significant main effects of transgene (F(1,30)=36.2; p<0.001; ηp2=0.547) and treatment (F(2,30)=8.36; p=0.001; ηp2=0.358), as well as transgene ′ treatment interaction (F(2,30)=5.06; p=0.013; ηp2=0.252) were observed for the Aβ(1-40) peptide. For the Aβ(1-42) peptide, statistically significant main effects of transgene (F(1,33)=85.0; p<0.001; ηp2=0.720) and treatment (F(2,33)=12.9; p<0.001; ηp2=0.439) were obtained for. Unlike DHED treatment (p < 0.001, d = 2.81), E2 did not have a statistically significant effect compared to the DTG-VEH group in reducing Aβ(1-40) levels in male DTG mice (Figure 2A). However, the DTG-VEH group had significantly higher level of Aβ(1-42) as compared to both the DTG-E2 (p < 0.001, d = 2.12) and DTG-DHED (p < 0.001, d = 2.53) groups. We also observed no significant difference between the DTG-E2 and DTG-DHED groups (Figure 2B).

Fig. 2. Aβ peptide levels in the brain of male NTG and DTG mice after treatment with vehicle, E2 and DHED.

Data are expressed as pg peptide/mg ± SEM (N = 5–7/group) determined by ELISA. (A) Aβ(1-40); (B) Aβ(1-42). *p<0.05 by ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s HSD test; effect sizes indicated by Cohen’s d values.

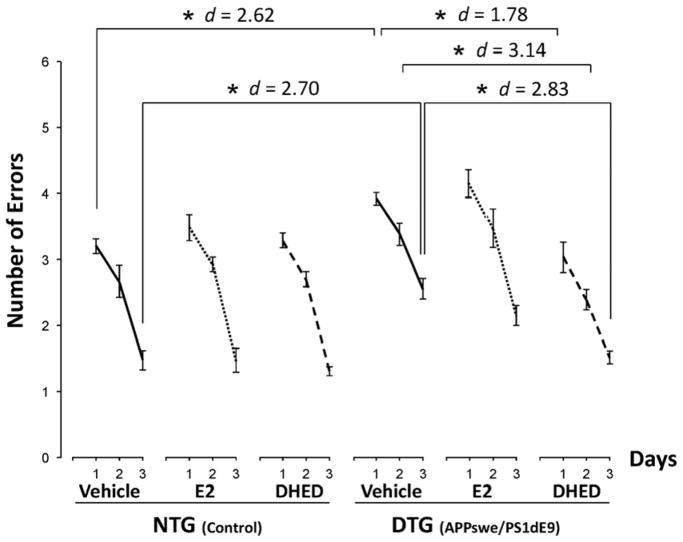

The main effect in the RAWM behavioral testing was associated with the number of trials (F(2,41) = 274.2; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.93), because errors decreased in comparison with the first trial upon retesting on the following day, and the animals committed the smallest number of errors on their last, third day of our testing. However, statistically significant effect of treatment (F(2,42) = 3.73; p = 0.032; ηp2 = 0.151) also was shown, while p for the introduced transgene was 0.050 (F(2,41) = 3.24; ηp2 = 0.136). Because our work was directed primarily on evaluating E2 and its brain-selective prodrug DHED in an animal model for AD, we therefore chose to focus our follow-up analyses on comprehensive assessment of treatments considering the entire RAWM experiment. After pairwise post hoc comparisons among groups and trials, initial differences in errors between the NTG and DTG vehicle-treated groups (NTG–VEH and DTG-VEH, respectively) were observed confirming the detrimental impact of the APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenes on learning (Fig. 3). On day 1, the NTG-VEH group performed with significantly less errors than the DTG-VEH treated group (p = 0.038, d = 2.62), while the DTG-DHED treated group outperformed both the DTG-VEH (p = 0.006, d = 1.78) and the DTG-E2 groups (p < 0.001, d = 1.96). On the second day of testing, the DTG-DHED group again made less errors compared to both the DTG-VEH (p = 0.006, d = 3.14) and the DTG-E2 group (p = 0.003, d = 1.92). On the last day of testing, the DTG-DHED group also outperformed both the DTG–VEH group (p < 0.001, d = 2.83) and the DTG-E2 group (p = 0.042, d =2.03). Altogether, while all DTG animals manifested learning over the 3-day testing period, DHED-treated mice showed the greatest ability to learn the task on days 1, 2 and 3 compared to vehicle- or E2-treated controls. DHED-treated mice performed as well as the NTG control males carrying no AD pathology, while E2 treatment had no statistically significant effect on learning based on RAWM testing in which there were no statistically significant difference between the E2-treated and the vehicle-treated control groups in DTG animals throughout the study.

Fig. 3. Radial arm water maze (RAWM) results of cognitive testing.

Male control (NTG) and transgenic (DTG) mice were dosed with vehicle, E2 or DHED, and effects on behavioral responses were compared. Number of errors are shown as averages for each day ± SEM (N = 7–9/group); within-group comparisons indicating that each additional trial significantly improved response are not displayed. DHED-treated DTG mice showed statistically significant improvement in ability to learn the task on days 1, 2 and 3 compared to vehicle-treated DTG controls, and performed like the NTG animals that manifested no behavioral impairment because they did not carry the APPswe/PS1dE9 transgene. *p<0.05 by repeated measures ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s HSD test; effect sizes indicated by Cohen’s d values.

Overall, our measurements support that E2 (by treatment directly with the hormone or delivered to the brain selectively by its prodrug DHED) effectively reduces APP to a level equal to that of the healthy NTG animals (Fig. 1). The mechanisms of E2’s effect on APP level may involve modulation of mRNA synthesis through alternative splicing (Thakur and Mani, 2005), induction of a rapid secretion of the protein via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (Manthey et al., 2001), and stimulation of APP’s proteolysis through the non-amyloidogenic pathway (Duarte et al., 2016). By inhibiting APP trafficking to the trans-Golgi network, E2 may also reduce Aβ formation by decreasing the substrate pool for amyloidogenic degradation of the protein (Greenfield et al., 2002). However, the dosage could require careful titration to avoid reducing APP to an extent that would have negative effects on endogenous activity of the protein relating to synaptogenesis and synaptic plasticity (Koike et al., 2012). Our findings also revealed that s. c. administration of E2 either directly or via its DHED prodrug was effective at decreasing both Aβ(1-40) and Aβ(1-42) (Fig. 2). Since Aβ(1-42) is more hydrophobic and thus plaque forming, reducing this particular form of Aβ may be the most beneficial in mitigating AD pathology. Of note, it has been shown that E2 treatment also prevented Aβ accumulation in gonadectomized males of a triple transgenic AD (3xTgAD) mouse model (Rosario et al. 2010; Carroll et al., 2012). Although the decreased levels of APP (Fig. 1) may be directly related to the decreased amount of Aβ, it is also possible that E2 affects Aβ formation through a different pathway. Stimulation of the expression or the activity of α-secretase resulting in decreased Aβ production (Jaffe et al., 1994) may be one of the mechanisms responsible for the beneficial effects of E2 in this regard. In addition, E2 has also been shown to diminish levels and activities of β-secretase (Amtul et al., 2010) and the γ-secretase complex (Jung et al., 2013).

Behavioral response seen in DTG male mice after DHED therapy was similar to those observed in DTG females (Tschiffely et al., 2016), indicating the gender-independent benefit of estrogen treatment in these models representing early stage of the disease. However, while treating directly with E2 was effective in female DTG mice (Tschiffely et al., 2016), such treatment was ineffective in DTG males (Fig. 3). The latter could be linked to a substantially less robust effect of direct E2 administration on Aβ peptide levels (Fig. 2). Adult female rats have also been found more responsive to the neuroprotective effects of E2 than males (Barker and Galea, 2008), which explains the observed gender differences upon direct treatment with the hormone regarding AD-associated behavioral improvement. On the other hand, the benefit of DHED-based estrogen therapy targeting the brain was its effectiveness (owing to improved “drug economy” resulting in an improvement of cognitive performance in the less responsive DTG males) combined with lack of peripheral hormone exposure that is unavoidable with any direct and non-invasive E2 administration (Prokai et al., 2015).

In conclusion, DHED-based estrogen treatment in the DTG mouse model of AD also was shown to decrease amyloid precursor protein and Aβ peptide levels concomitantly improving learning in male animals at an early stage of the neuropathology. With brain-selective estrogen therapy (thus, without exposing the rest of the body to the hormone), DHED offers unprecedented benefits and therapeutic safety for an early intervention.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments and financial disclosures

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AG031387 (MAO), AG031535 and CA21550 (LP), and EY027005 (KP), as well as by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (endowment BK-0031, LP), the VA Research Service Rehabilitation R&D REAP (RAS), the Biomedical R&D CDA02 (RAS), and was conducted in partial fulfillment of the Ph.D. requirements for the University of Maryland (AET). L.P. and K.P.-T. have equity interests in AgyPharma LLC and are co-inventors of US Patents 7,026,306 and 7,300,926 on the use of DHED. All other authors disclose no financial interest or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Alamed J, Wilcock DM, Diamond DM, Gordon MN, Morgan D. Two-day radial-arm water maze learning and memory task; robust resolution of amyloid-related memory deficits in transgenic mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1671–1679. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amtul Z, Wang L, Westaway D, Rozmahel RF. Neuroprotective mechanism conferred by 17β-estradiol on the biochemical basis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2010;169:781–786. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JM, Galea LAM. Repeated estradiol administration alters different aspects of neurogenesis and cell death in the hippocampus of female, but not male, rats. Neuroscience. 2008;152:888–902. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum LW. Sex, hormones, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:736–743. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekris LM, Yu CE, Bird TD, Tsuang DW. Genetics of Alzheimer disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2010;23:213–227. doi: 10.1177/0891988710383571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird TD. Genetic aspects of Alzheimer disease. Gen Med. 2008;10:231–239. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31816b64dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box GEP, Hunter SJ, Hunter WG. Statistics for Experimenters: Design, Innovation, and Discovery. 2. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, NJ: 2005. pp. 317–333. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD. Effect size and eta squared. JALT Test Eval SIG Newsl. 2008;12:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan MJ, Lipinski WJ, Bian F, Durham RA, Pack A, Walker LC. Augmented senile plaque load in aged female beta-amyloid precursor protein-transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1173–117. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64064-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JC, Rosario ER. The Potential Use of hormone-based therapeutics for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:18–34. doi: 10.2174/156720512799015109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CL, Resnick EM, Mallampalli M, Kalbarczyk A. Sex and gender differences in Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations for future research. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:1018–1023. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Correia SC, Santos RX, Cardoso S, Carvalho C, Santos MS, Oliveira CR, Moreira PI. Effects of estrogen in the brain: is it a neuroprotective agent in Alzheimer’s disease? Curr Aging Sci. 2010;3:113–126. doi: 10.2174/1874609811003020113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey DA. Prevention of Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrovascular disease and dementia in women: the case for menopause hormone therapy. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2017;7:85–94. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2016-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte AC, Hrynchak MV, Goncalves I, Quintela T, Santos CRA. Sex hormone decline and amyloid β synthesis, transport and clearance in the brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2016;28 doi: 10.1111/jne.12432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield JP, Leung LW, Cai D, Kaasik K, Gross RS, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Greengard P, Xu H. Estrogen lowers Alzheimer beta-amyloid generation by stimulating trans-Golgi network vesicle biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12128–12136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen T, Kalesnykas G, Rissanen A, Tapiola T, Iivonen S, Wang J, Chaudhuri J, Tanila H, Miettinen R, Puoliväli J. Estrogen treatment improves spatial learning in APP + PS1 mice but does not affect beta amyloid accumulation and plaque formation. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine K, Laws KR, Gale TM, Kondel TK. Greater cognitive deterioration in women than men with Alzheimer’s disease: A meta analysis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34:989–998. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2012.712676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AB, Toran-Allerand CD, Greengard P, Gandy SE. Estrogen regulates metabolism of Alzheimer amyloid beta precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13065–13068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowsky JL, Fadale DJ, Anderson J, Xu GM, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Lee MK, Younkin LH, Wagner SL, Younkin SG, Borchelt DR. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:159–170. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JI, Ladd TB, Kukar T, Price AR, Moore BD, Koo EH, Golde TE, Felsenstein KM. Steroids as γ-secretase modulators. FASEB J. 2013;27:3775–3785. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-225649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike MA, Lin AJ, Pham J, Nguyen E, Yeh JJ, Rahimian r, Tromberg BJ, Choi B, Green KN, LaFerla FM. APP knockout mice experience acute mortality as the result of ischemia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan YL, Zhao J, Li S. Update on the neuroprotective effect of estrogen receptor alpha against Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:1137–1148. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws KR, Irvine K, Gale TM. Sex differences in cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. World J Psychiatry. 2016;22:54–65. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo A, Launer LJ, Fratiglioni L, Andersen K, Di Carlo A, Breteler MM, Copeland JR, Dartigues JF, Jagger C, Martinez-Lage J, Soininen H, Hofman A. Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: A collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic diseases in the elderly research group. Neurology. 2000;54:S4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthey D, Heck S, Engert S, Behl C. Estrogen induces a rapid secretion of amyloid beta precursor protein via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:4285–4291. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchenthaler I, Lane M, Sabnis G, Brodie A, Nguyen V, Prokai L, Prokai-Tatrai K. Treatment with an orally bioavailable prodrug of 17β-estradiol alleviates hot flushes without hormonal effects in the periphery. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30721. doi: 10.1038/srep30721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. Water maze tasks in mice: special reference to Alzheimer’s transgenic mice. In: Buccafusco JJ, editor. Methods of Behavior Analysis in Neuroscience. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musicco M. Gender differences in the occurrence of Alzheimer’s disease. Funct Neurol. 2009;24:89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokai L, Nguyen V, Szarka S, Garg P, Sabnis G, Bimonte-Nelson HA, McLaughlin KJ, Talboom JS, Conrad CD, Shughrue PJ, Gould TD, Brodie A, Merchenthaler I, Koulen P, Prokai-Tatrai K. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:297ra113. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokai L, Prokai-Tatrai K, Perjesi P, Zharikova AD, Perez EJ, Liu R, Simpkins JW. Quinol-based cyclic antioxidant mechanism in estrogen neuroprotection. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11741–11746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2032621100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokai-Tatrai K, Perjesi P, Rivera-Portalatin NM, Simpkins JW, Prokai L. Mechanistic investigations on the antioxidant action of a neuroprotective estrogen derivative. Steroids. 2008;73:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokai-Tatrai K, Xin H, Nguyen V, Szarka S, Blazics B, Prokai L, Koulen P. 17β-estradiol eye drops protect the retinal ganglion cell layer and preserve visual function in an in vivo model of glaucoma. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:3253–3261. doi: 10.1021/mp400313u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiserer RS, Harrison FE, Syverud DC, McDonald MP. Impaired spatial learning in the APPSwe + PSEN1DeltaE9 bigenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:54–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario ER, Carroll J, Pike CJ. Testosterone regulation of Alzheimer-like neuropathology in male 3xTg-AD mice involves both estrogen and androgen pathways. Brain Res. 2010;1359:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin BB. Estrogen and memory in women: how can we reconcile the findings? Horm Behav. 2005;47:371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschiffely AE, Schuh RA, Prokai-Tatrai K, Prokai L, Ottinger MA. A comparative evaluation of treatments with 17β-estradiol and its brain-selective prodrug in a double-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hormon Behav. 2016;83:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Bernhardi R, Eugenin J. Alzheimer’s disease: redox dysregulation as a common denominator for diverse pathogenic mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:974–1031. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton W, Gleason CE, Lorenze KR, Markgraf TS, Ries ML, Carlsson CM, Asthana S. Potential role of estrogen in the pathobiology and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Transl Res. 2009;20:131–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagni E, Simoni L, Colombo D. Sex and gender differences in central nervous system-related disorders. Neurosci J. 2016;2016:2827090. doi: 10.1155/2016/2827090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]