Highlights

-

•

WHO vaccine hesitancy definition understood; >90% countries report hesitancy.

-

•

Long list of reasons, varied by country income level; WHO region, changed overtime.

-

•

Most cited: risk-benefit (scientific evidence) equaled <25% of reasons cited.

-

•

Reasons cited based on assessments in only 1/3 of countries; need to increase this.

Keywords: Vaccine hesitancy, Joint Reporting Form (JRF), Vaccines, Attitudes to vaccines, Vaccine confidence, Vaccine acceptance, SAGE

Abstract

In order to gather a global picture of vaccine hesitancy and whether/how it is changing, an analysis was undertaken to review three years of data available as of June 2017 from the WHO/UNICEF Joint Report Form (JRF) to determine the reported rate of vaccine hesitancy across the globe, the cited reasons for hesitancy, if these varied by country income level and/or by WHO region and whether these reasons were based upon an assessment. The reported reasons were classified using the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization matrix of hesitancy determinants (www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf). Hesitancy was common, reported by >90% of countries. The list of cited reasons was long and covered 22 of 23 WHO determinants matrix categories. Even the most frequently cited category, risk- benefit (scientific evidence e.g. vaccine safety concerns), accounted for less than one quarter of all reasons cited. The reasons varied by country income level, by WHO region and over time and within a country. Thus based upon this JRF data, across the globe countries appear to understand the SAGE vaccine hesitancy definition and use it to report reasons for hesitancy. However, the rigour of the cited reasons could be improved as only just over 1/3 of countries reported that their reasons were assessment based, the rest were opinion based. With respect to any assessment in the previous five years, upper middle income countries were the least likely to have done an assessment. These analyses provided some of the evidence for the 2017 Assessment Report of the Global Vaccine Action Plan recommendation that each country develop a strategy to increase acceptance and demand for vaccination, which should include ongoing community engagement and trust-building, active hesitancy prevention, regular national assessment of vaccine concerns, and crisis response planning (www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2017/october/1_GVAP_Assessment_report_web_version.pdf).

1. Introduction

In 2014 the World Health Organization Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) Report from the Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy was accepted [1]. The Working Group developed (1) a definition of vaccine hesitancy: the “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place and vaccines. It is influenced by factors such as complacency, convenience and confidence” and (2) a vaccine hesitancy determinants matrix that included contextual influences, individual and group influences and vaccine/vaccination specific issues that could be used to categorize specific reasons for vaccine hesitancy [1], [2]. The Working Group also defined two indicators to monitor vaccine hesitancy [1].

1.1. Indicator 1: Reasons for vaccine hesitancy

-

•

Question 1: what are the top three reasons for not accepting vaccines according to the national schedule?

-

•

Question 2: is this response based on or supported by some type of assessment, or is it an opinion based on your knowledge and expertise?

1.2. Indicator 2: Percentage of countries that have assessed the level of hesitancy towards vaccination at the national or subnational level in the previous five years.

-

•

Question 1: has there been some assessment (or measurement) of the level of hesitancy in vaccination at national or subnational level in the past (<5 years)?

-

•

Question 2: if yes, please specify the type and year and provide assessment title(s) and reference(s) to any publication or report.

These indicators were pilot tested and then introduced into the 2014 WHO/UNICEF Joint Report Form (JRF) and subsequently included in the 2015 and 2016 JRF. Review of the 2014 JRF vaccine hesitancy data revealed that vaccine hesitancy was present in the majority of countries with safety being the biggest concern albeit differences were noted across WHO regions [3]. Given that as of the end of June 2017, three years of JRF data on vaccine hesitancy were now available (2014, 2015 and 2016), an analysis was undertaken to gather a global picture of hesitancy and whether this was changing over time by reviewing (a) the reported presence of hesitancy, (b) the reasons across the globe based upon assessment or opinion, and (c) the variability in the reasons by country income level and by WHO region.

2. Methods

The methods outlined in Marti et al [3] used for the 2014 analysis were followed for assessment of the 2014, 2015 and 2016 data. Data were compiled using Microsoft Excel version 15.36 and were analyzed using SPSS version 24. The JRF response rates were calculated using all World Health Organization (WHO) Member States (194) for the denominator with the exception of the analysis of assessment rates in Indicator 1 and 2 (regional and income level analysis) where the denominator used for Indicator 1 was the number of countries that responded to any JRF Indicator 1 questions that year; and for indicator 2 the number of countries that responded to any JRF indicator 1 or 2 question that year. Translation of non-English responses was completed by the WHO with back translations done to improve accuracy. Income level groupings were based on the World Bank Development Indicators for the respective years of the data (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator). Country Population data was United Nations Population Data from July 2017(https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/).

As was done for the 2014 data [3], the responses were categorized using the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy determinants matrix [1], [2]. This was completed by the same 2 reviewers for all three years. If there were discrepancies between the two categorizers, then a third reviewer was consulted to arrive at a final decision. Based upon the 2015 data, a list of all responses assigned to each matrix category was compiled and reviewed to ensure internal uniformity. This list was then used to help categorize the 2016 and 2014 responses in order to enhance consistency of response assignment to a specific category across the three years. All available data as of June 30, 2017 was used in the analysis. Of note, based upon previous years JRF reporting an additional 10–12 countries will likely submit final 2016 data by the end of 2017.

If a country’s response to Indicator 1 question 1 was “no” “none” or “no hesitancy” this was coded as no hesitancy. Given the request for three responses to question 1, if the answers were repeated, for example “No” was stated three times as had requested three responses, this was only coded once. When a response could not be assigned to a matrix determinant category, it was placed in “other”.

With respect to Indicator 1 Question 2 i.e. was the response about reasons based upon an assessment or on opinion, these were recorded as a yes if an assessment was noted and no if opinion was noted. If left blank this was recorded as a no. With respect to Indicator 2 concerning assessments in the previous five years, as was done in 2014 [3], if an assessment title was provided then it was coded that the country had completed an assessment even if the question had been left blank or answered “no” in the JRF query. If the “Assessment title” query was left blank but there was a response to question whether or not an assessment was done, then “assessment title” was coded as “no title provided” not as “no answer provided”.

3. Results

3.1. Indicator 1

3.1.1. Response rates

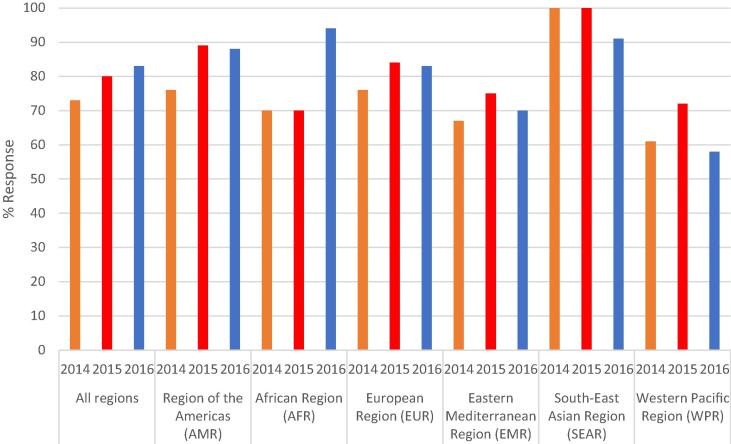

The overall JRF response rates were similar over the three years; 2014 95% (185/194), 2015 98% (190/194) and 2016 95% (184/194). However, the response rates to the first vaccine indicator question were lower but increased each year; 2014 73% (141/194), 2015 77% (150/194) and 2016 78% (152/194). The increase was not consistent across the WHO regions as shown in Fig. 1. For example, between 2015 and 2016 the response rates increased in the African Region (AFR) with only slight changes in the other regions.

Fig. 1.

Response rates to the query what are the top 3 reasons for not accepting vaccines according to the national schedule reported by countries in the 6 WHO regions over the past 3 years.

3.1.2. No hesitancy

The number of countries that reported no hesitancy remained relatively consistent over the 3 years and overall was low; 2014 – 12 countries (6%), 2015–14 countries (7%) and 2016–14 (7%). More recently i.e. in 2016, the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) and South East Asia Region (SEAR) reported “no vaccine hesitancy” relatively more often than in other regions e.g. 4/21 (19%) countries from EMR and 4 /11 (36%) from SEAR.

3.1.3. Reasons for vaccine hesitancy

3.1.3.1. Assessment or opinion: Basis for reasons provided

For Indicator 1, countries reported that the reasons provided were predominately based upon opinion as only 36% (50/141) in 2014, 39% (58/150) in 2015 and 38% (57/152) in 2016 noted these were based on an assessment.

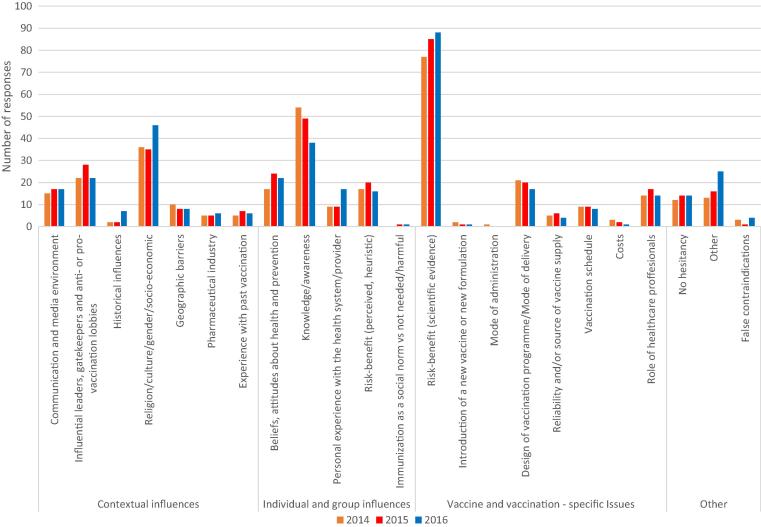

A total of 1110 reasons were given for hesitancy over the three years; 352 in 2014, 376 in 2015 and 382 as of June 30, 2016. As shown in Fig. 2 the top three cited reasons for vaccine hesitancy globally in these three years were consistently: (1) risk–benefit (scientific evidence) (22%, 23%, 23%) e.g. “vaccine safety concerns”, “fear of side effects”; (2) lack of knowledge and awareness of vaccination and its importance (15%, 13%, 10%) e.g.”lack of knowledge of parent on benefit of immunization”; and 3) religion, culture, gender and socioeconomic issues regarding vaccines (10%, 9%, 12%) e.g. “due to certain religious sects(minority)”, “traditional cultural beliefs”. The frequency of risk-benefit (scientific evidence) slightly increased from 22% in 2014 to 23% in 2015 and in 2016 and both knowledge and awareness and religion/culture/gender/socio-economic never had more than a 3% change per year over the three years. Of note, all matrix determinant categories except one (politics, policies) had at least one response assigned in the three years.

Fig. 2.

The main 3 reasons reported by countries for vaccine hesitancy classified in vaccine hesitancy matrix categories in the past 3 years.

There were differences overall in the top three reasons cited between those who reported having done an assessment versus no assessment in 2014 and 2015 but not in 2016. In 2016, there were no differences and the top three reasons cited in both sets of countries were the same three as noted above. In 2014 and 2015, for those who reported having done an assessment design of vaccination program/mode of delivery was in the top three, i.e. a difference, along with risk–benefit (scientific evidence) and lack of knowledge and awareness of vaccination for countries. In 2014 countries reporting no assessment, the top three reasons cited were the same three as noted above overall (risk benefit, religion, lack of knowledge). In 2015, the top three reasons in no assessment countries included the same first two (risk benefit and religion) but the third reason cited was influential leaders, immunization programme gatekeepers and anti-or pro-vaccination lobbies.

3.1.4. Other

Only a small number of responses did not fit into a matrix determinant category in each of the three years; 3.7% in 2014, 4.3% in 2015 and 6.5% in 2016. Review of these “other” responses revealed most could not be categorized due to the brevity of response. e.g. “affluence,” “poor demand” and “obstacles” without further modifiers to explain. “Obstacles” could have meant vaccine clinic access obstacles, individual obstacles such as fathers and mothers disagreeing on importance of immunization or even fear of needles. This made selecting only one matrix determinant category impossible.

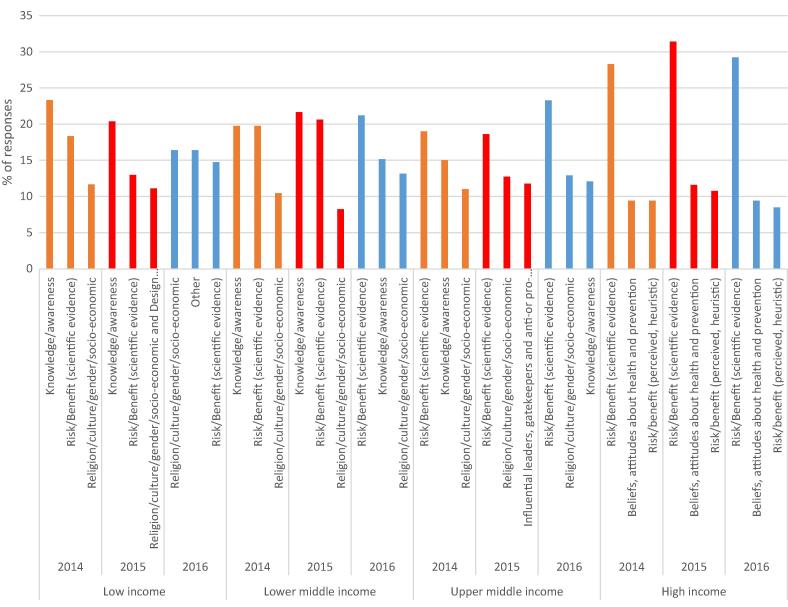

3.1.5. Hesitancy reasons by country income level

The reported reasons for hesitancy compared by country income level (low income, lower middle-income, upper middle-income and high-income, according to the World Bank grouping are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Frequency of main reasons reported by countries for vaccine hesitancy classified in vaccine hesitancy matrix categories by country income level over the past 3 years.

Knowledge/Awareness was the number one reason in low income countries in 2014 and 2015 but the rate fell from 23% to 11% and by 2016 had fallen to 6% and into fourth place as the most cited reason. In lower middle income countries the change was less extreme; 17% in 2014, 21% in 2015 and 15% in 2016. In upper middle income countries risk/benefit (scientific evidence) was the most commonly cited reason across all three years with only slight changes; 19%, 19% and 23%. In high income countries, risk benefit (scientific evidence) remained the most commonly cited reason across all three years with relative consistency of 28%, 31% and 29% in 2014, 2015 and 2016 respectively.

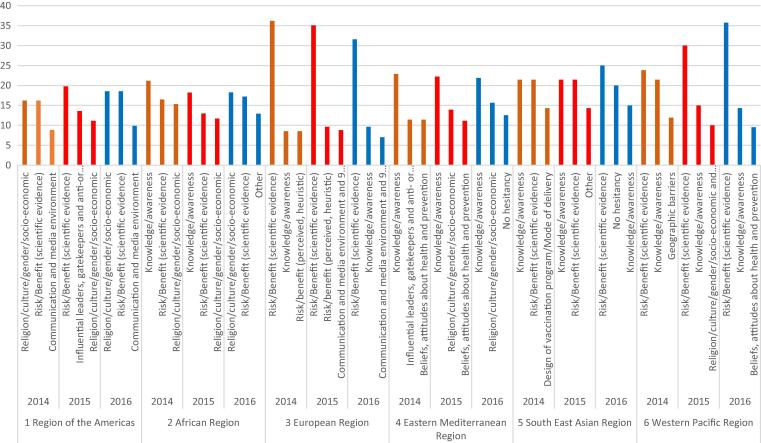

3.1.6. Hesitancy reasons by WHO region

Fig. 4 shows that the top three reasons for vaccine hesitancy varied by WHO region. The overall top three reasons (risk/benefit (scientific evidence), knowledge/awareness and Religion/culture/socio-economic) were not necessarily the top three in every region nor in the same order in all regions where these appeared.

Fig. 4.

Frequency of main reasons reported by countries for vaccine hesitancy classified in vaccine hesitancy matrix categories by WHO region over past 3 years.

3.1.7. Cited reasons in a country over time

Review of all responses at the individual country level revealed similarities in reported reasons over the three years in many countries but in some major changes had occurred. For example in Country A from 2014 to 2015 there was no major changes in the top three reasons for vaccine hesitancy, (“skeptical about the effectiveness of vaccines”, “no halal certification of vaccines” and “skeptical about the safety of vaccines”) but in 2016 “practice homeopathic medications” was now in the top three reasons without any mention of halal concerns. Discussion with the country revealed that an intervention to address the halal vaccine concern had been carried out and an assessment had then shown that this was no longer a major concern.

3.2. Indicator 2

3.2.1. Assessment of vaccine hesitancy in previous five years

In 2016 145 (79%) countries out of the 184 WHO Member States that submitted their JRF responded to the second indicator. This was similar for 2015 (80%) and a slight increase from 2014 (77%). The number of countries that reported having completed an assessment related to vaccine hesitancy in the last five years stayed relatively consistent across the three years; 29% (56/194) in 2014, 36% (69/194) in 2015 and 33% (63/194) in 2016 as shown in Table 1. The rate of assessments varied across the six WHO regions. (Table 2) and by country income level (Table 3). An analysis of the assessment type was not done due to lack of data.

Table 1.

Overall rates of assessment of vaccine hesitancy by countries in the past 5 years based upon responses in the WHO UNICEF Joint Reporting Form (JRF) over the past 3 years.

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment completed n (%) | 56 (29) | 69 (36) | 63 (32) |

| No Assessment n (%) | 86 (44) | 82 (42) | 82 (42) |

| Question not completed but at least one response to a JRF vaccine hesitancy question n (%) | 52 (27) | 43 (22) | 49 (25) |

| No. of countries responded to at least one JRF vaccine hesitancy question | 185/194 | 190/194 | 184/194 |

Table 2.

Rates of assessment of vaccine hesitancy by countries in the past 5 years by WHO Region based upon responses to any JRF Indicator questions over the past 3 years.

| 2014 N (%) | 2015 N (%) | 2016 N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Americas | 4 (13) | 9 (28) | 6 (19) |

| African | 21 (51) | 20 (48) | 21 (48) |

| European | 15 (41) | 22 (52) | 21 (51) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 5 (31) | 7 (47) | 7 (47) |

| South East Asian | 5 (46) | 5 (46) | 2 (20) |

| Western Pacific | 6 (33) | 6 (32) | 6 (43) |

Table 3.

Rates of assessment of vaccine hesitancy by countries in the past 5 years by country income level based upon responses to any JRF Indicator questions in the past 3 years*.

| 2014 N (%) | 2015 N (%) | 2016 N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low income | 14 (54) | 13(46) | 14 (47) |

| Lower middle income | 21(51) | 23 (53) | 19 (45) |

| Upper middle income | 8 (19) | 14 (33) | 10 (22) |

| High income | 13 (30) | 19 (42) | 20 (53) |

Excludes countries with <20,000 population.

4. Discussion

Since the vaccine hesitancy indicator question, including the WHO SAGE vaccine hesitancy definition, was first introduced into the JRF in 2014, the response rate to Indicator 1 questions has increased each year with the 2016 rate as of June 30, 2017 at 78%, 5% higher than in 2014. This increase will likely be even larger once late arriving JRF data for 2016 i.e. receipt after June 30, 2017 are included. The responses provided indicate that the SAGE vaccine hesitancy definition is well understood around the globe. This is reassuring and values the effort the SAGE Working Group put into developing a practical easily understood definition [4] especially given the concerns raised recently that the term vaccine hesitancy merited more precision [5]. Furthermore, this three year JRF review also provides evidence that the WHO determinants matrix is practical for categorizing reasons cited for vaccine hesitancy as over 95% of the cited reasons fit into a matrix determinant category. Responses that did not fit were often due to their brevity. Potentially this problem could be addressed by encouraging more than one word answers to the JRF query.

Unfortunately, countries reported that the majority of reasons cited for hesitancy in Indicator 1 were not based upon an assessment but on opinion over these three years. It is encouraging that more are being based upon assessments but this was still only 38% in 2016. Furthermore, for Indicator 2, the number of countries that reported having completed an assessment of vaccine hesitancy in the previous five years remained relatively low overall at just over 30% in each of the three years. The rates varied markedly by region and also by country income level with upper middle income countries being the least likely to have reported having done an assessment. It remains unclear why so few countries are carrying out assessments given their value for tailoring interventions to better address hesitancy both at the national level and in subgroups [6], [7]. Assessments are also key for determining if an intervention has been effective in reducing overall hesitancy The observation that upper middle income countries were the least likely to have done an assessment deserves attention to determine the barriers to assessment. Is it a lack of survey tools in the language needed by the country? Lack of skills and resources to carry out an assessment? Lack of priority?

This three year JRF review confirms that hesitancy is present in the majority of countries globally with less than 10% reporting no hesitancy. The top three categories for most cited reasons globally remained relatively consistent over the three years but varied by country income level and by region, emphasizing that hesitancy is not uniform. These categories were risk-benefit (scientific evidence), knowledge and awareness and religion/culture/gender/socio-economic. The rate of responses falling into these three categories remained relatively constant over the three years with the percent change of only 3% or less highlighting their ongoing importance globally. However, overall even the most frequently cited categories (risk-benefit (scientific evidence)) only accounted for less than one quarter of all categories cited emphasizing the complexity and variability of hesitancy globally. Furthermore, this three -year review also found that the reasons for hesitancy did not necessarily remain static within a country over time underlining not only the importance of assessments to determine if a common concern exists that can be addressed through a targeted national campaign but also the value of evaluation to assess if interventions have been effective.

The trends and changes in the major category of reasons for hesitancy by country income level has implications for programs aimed at helping to address hesitancy from WHO regional offices, UNICEF, international non-governmental organizations and partners. By 2016, in low income countries, knowledge and awareness had dropped out of the top three category for vaccine hesitancy, and religion/culture/gender/socioeconomic had moved up. Additionally, in lower middle income countries there was a shift towards the top three categories looking more like upper middle income and high income countries as by 2016 knowledge/awareness had dropped from being the top category and risk-benefit (scientific evidence) had become more prominent. Evaluating trends over time will be helpful in assessing the effectiveness of both regional and individual country intervention efforts.

There are several limitations to this three year analysis. First, when categorizing the cited reason using the WHO matrix of determinants, in some instances answers fit into more than one category. Imprecision and paucity of the information provided, as noted above, raised challenges in some instances for category placement. Secondly, the classification of the provided reasons may have been subject to personal perception although this was mitigated to some extent by the independent vetting by two authors and the use of the complied list to increase consistency year over year. Thirdly, the limited number of country assessment means the reasons were predominately based upon the impressions of those completing the JRF not on specific direct measurements. Fourthly, as noted by Grabenstein in his review of world religions and vaccines, religious reasons may not be based upon religious teachings but may reflect safety and other concerns [8].Hence some of the reports placed in this category might well have fitted into the risk-benefit (scientific evidence) category if more fulsome information had been provided.

Vaccine hesitancy is only one component of vaccine demand in the Global Vaccine Action Plan [9]. The 2016 JRF included indictors for vaccine demand for the first time. There are lessons to be learned from this JRF vaccine hesitancy three year review that may be helpful for assessing vaccine demand JRF data globally. While a UNICEF WHO definition of vaccine demand has been developed [10], this was not included as part of the 2016 newly introduced JRF demand question. Thus different countries may have interpreted the demand question in different ways. Secondly, a demand matrix for categorizing determinants is only in the development phase and has not been validated for categorizing the responses. These concerns may make interpretation of the initial demand JRF data more difficult.

In summary, across the globe countries appear to understand the SAGE vaccine hesitancy definition and are able to report on it. The WHO matrix of determinants proved to be robust for categorizing the reasons. The three year hesitancy JRF results have shown that hesitancy is common but the list of cited reasons long. Even the most frequently cited category, risk- benefit (scientific evidence), only accounted for less than one quarter of all reasons but does highlight an area to focus on that might have some impact in many countries. The quality and validity of the reporting could be improved if more reports were based upon assessments. For this to happen, the barriers to undertaking assessments need to be determined. Increasing assessments would not only enhance the validity of the reasons cited but when done serially e.g. before and after an intervention has been implemented could help grow the evidence for what strategies work in what settings and in what contexts to improve vaccine acceptance. In the interim, when stakeholders are working with countries to address hesitancy and improve vaccine acceptance, if assessments are not available, it might be helpful to look at both regional trends as well as trends by country income level to determine what concerns might most effectively be targeted to help the country.

Finally, the findings of this analysis provided some of the evidence for the 2017 Assessment Report of the Global Vaccine Action Plan recommendation that each country develop a strategy to increase acceptance and demand for vaccination, which should include ongoing community engagement and trust-building, active hesitancy prevention, regular national assessment of vaccine concerns, and crisis response planning [11].

Funding

Funded in part by Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine Research in Medicine program for students; Sarah Lane received summer funding from the Ross Stuart Smith Studentship fund. Ethics approval from IWK Health Centre, Halifax, Canada.

Disclaimer

Some of the authors are World Health Organization staff members. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the decisions, official policy or opinions of the World Health Organization.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf [accessed Dec 11, 2017].

- 2.MacDonald NE, & SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine Hesitancy: defintion, scope and determinants. Vaccine,2015;33, 4161–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Marti M, de Cola M, MacDonald NE, Dumolard L, Duclos P. Assessments of global drivers of vaccine hesitancy in 2014-Looking beyond safety concerns. PLoS One. 2017, March 1, 12(3), e0172310. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.MacDonald N, Dubé E, Butler R. Vaccine hesitancy terminology; a response to Bedford et al. Vaccine 2017; Nov 2pii: S0264-410X(17)31644-http://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Beford H, Atwell K, Danchin M, Marshall H, Corben P, Leask J. Vaccine hesitancy, refusal and access barriers: the need for clarity in terminology. Vaccine 2017 Aug 19. pii: S0264-410X(17)31070-8. http://doi.org/10.1016/j. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Butler R, MacDonald NE; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Diagnosing the determinants of vaccine hesitancy in specific subgroups: the guide to tailoring immunization programmes (TIP). Vaccine. 2015, 14; 33(34):4176–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Van Damme P, Lindstrand A, Kulane A, Kunchev A. Commentary to: guide to tailoring immunization programmes in the WHO European Region. Vaccine. 2015, 26; 33(36):4385–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Grabenstein D. What the world's religions teach, applied to vaccines and immune globulins. Vaccine. 2013;31(16):2011–2023. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011-2020. <http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/> [accessed Dec 11, 2017].

- 10.Hickler B, MacDonald NE, Senouci K, Schuh HB and the informal Working Group on Vaccine Demand (iWGVD) for the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on immunization (SAGE) Working Group on Decade of Vaccines. Efforts to monitor Global progress on individual and community demand for immunization: development of definitions and indicators for the Global Vaccine Action Plan Strategic Objective 2. Vaccine 2017; 35(28): 3515–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.World Health Organization. 2017 Assessment report of the global vaccine action plan. Strategic group of experts on immunization. <http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2017/october/1_GVAP_Assessment_report_web_version.pdf> [accessed Dec 11, 2017].