Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: acupuncture, dysmenorrhea, meta-analysis, primary dysmenorrhea, systematic review

Abstract

Background:

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the current evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of acupuncture on primary dysmenorrhea.

Methods:

Ten electronic databases were searched for relevant articles published before December 2017. This study included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of women with primary dysmenorrhea; these RCTs compared acupuncture to no treatment, placebo, or medications, and measured menstrual pain intensity and its associated symptoms. Three independent reviewers participated in data extraction and assessment. The risk of bias in each article was assessed, and a meta-analysis was conducted according to the types of acupuncture. The results were expressed as mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

This review included 60 RCTs; the meta-analysis included 49 RCTs. Most studies showed a low or unclear risk of bias. We found that compared to no treatment, manual acupuncture (MA) (SMD = −1.59, 95% CI [−2.12, −1.06]) and electro-acupuncture (EA) was more effective at reducing menstrual pain, and compared to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), MA (SMD = −0.63, 95% CI [−0.88, −0.37]) and warm acupuncture (WA) (SMD = −1.12, 95% CI [−1.81, −0.43]) were more effective at reducing menstrual pain. Some studies showed that the efficacy of acupuncture was maintained after a short-term follow-up.

Conclusion:

The results of this study suggest that acupuncture might reduce menstrual pain and associated symptoms more effectively compared to no treatment or NSAIDs, and the efficacy could be maintained during a short-term follow-up period. Despite limitations due to the low quality and methodological restrictions of the included studies, acupuncture might be used as an effective and safe treatment for females with primary dysmenorrhea.

1. Introduction

Primary dysmenorrhea is defined as cramping pain during menstruation without any identifiable pelvic pathology,[1] and it affects most women throughout the menstrual years.[2] Many studies have reported that the prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea varied from approximately 50% to 90%,[3–6] and 13% to 51% had to limit daily activities, such as school or work absenteeism.[2] In the consensus guidelines of primary dysmenorrhea,[7] nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and oral contraceptives (OCs) are recommended as first-line treatments. However, some patients did not experience pain reduction with NSAIDs and did experience side effects such as nausea, dyspepsia, headache, or drowsiness.[8,9] In addition, OCs may not be suitable for patients attempting to become pregnant, and might cause adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, weight gain, or vaginal bleeding.[10,11]

Acupuncture, derived from China, is a therapeutic modality using the insertion of fine needles with the concepts of Yin and Yang and the circulation of qi. Acupuncture acts primarily by stimulating the nervous system, by local effects due to local antidromic axon reflexes, and by releasing opioid peptides and serotonin. Today, acupuncture is regarded as part of conventional medicine. It is no longer only “alternative medicine,” and it is used in Western medicine.[12] In particular, acupuncture has been widely used to alleviate diverse pains[13] including menstrual pain.

Many clinical trials had been conducted to show efficacy of acupuncture on menstrual pain, and 6 systematic reviews (SRs) have been previously conducted to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture on primary dysmenorrhea.[14–19] However, the previous SRs included acupressure, the stimulation of acupoints without skin penetration,[14–18] which made the evaluation of acupuncture difficult. Some studies analyzed all types of acupuncture together,[14–17] which increased the heterogeneity. One latest study[19] included all the types of acupuncture except acupressure and analyzed the results separately, but it did not include newly published studies in 2017. Thus, we found it necessary to conduct a study with rigorous criteria that excluded acupressure and included all other types of acupuncture that penetrate the skin, such as embedding therapy, and to synthesize the data according to the type of acupuncture to reduce heterogeneity. We conducted this study with these criteria to determine the efficacy and safety of acupuncture on primary dysmenorrhea.

2. Methods

2.1. Study registration

The protocol for this study was registered in PROSPERO: CRD42017069258.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

2.2.1. Types of studies

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that measured pain intensity and related outcomes to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Case studies, case series, noncontrolled trials, review articles, letters, conference papers, abstracts, and poster presentations were excluded. Studies not written in English, Chinese, or Korean were also excluded.

2.2.2. Types of participants

We included female patients of reproductive age suffering from primary dysmenorrhea. The definition of primary dysmenorrhea was based on cyclic pelvic pain during menstruation without any gynecological pathology such as endometriosis, adenomyosis, or uterine myoma. Patients with secondary dysmenorrhea or serious medical conditions were excluded.

2.2.3. Types of interventions

Manual acupuncture (MA), electroacupuncture (EA), auricular acupuncture (AA), and any other type of acupuncture using needle insertion were included in our study. Pharmacopuncture and acupressure were excluded. Other types of acupuncture that are rarely used in Korean clinical practice, such as eye acupuncture and floating acupuncture were also excluded. Types of control interventions included in our studies were no treatment, placebo acupuncture, and oral medications such as NSAIDs and OCs. Herbal medicines or other traditional medicine treatments used in the control group were excluded from our study.

2.2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was pain intensity after the intervention period as measured by any validated scale, such as the visual analog scale (VAS) or numeric rating score (NRS). The secondary outcomes were pain relief measured by total effective rate (TER) or improvement rate; related symptoms measured by the seven-point verbal rating scale (VRS), Cox menstrual symptom scale (CMSS), Cox retrospective symptom scale (RSS), or menstrual symptom score (MSS); quality of life as measured by the 36-item Short Form health survey (SF-36); pain intensity after a follow-up period; and adverse events (AEs).

2.3. Data sources

The following databases were searched for articles published from the database's inception to December 2017: MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), Citation Information by NII (CiNii), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database (VIP), Wanfang, Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System (OASIS), and the Korean Traditional Knowledge Portal (Korean TK). There was no language restriction. We used Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and their synonyms, and modified the terms according to the strategy of each database. The search terms used are shown in Supplemental Search Terms List.

2.4. Study selection

All studies found based on the search results were saved into EndNote; duplicated studies were excluded. After deleting the duplicates, 3 reviewers, WHL, HSJ, and LHJ, selected the relevant studies independently by title and abstract, and finally selected the included studies using the full text. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion among the 3 reviewers and an arbiter, PKS.

2.5. Data extraction

Three authors, WHL, HSJ, and LHJ, extracted data from the included studies according to the predetermined data forms. The following items were extracted: baseline demographics (journal, author, and year of publication); participants (sample size, sex, and age); intervention (type of acupuncture, periods, and frequency of treatment, and follow-up period); control; and outcome.

2.6. Risk of bias assessment

WHL, HSJ, and LHJ independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study using the following criteria from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions[20]: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data; and selective reporting. We assessed these 6 criteria using “Low” (“L”), “Unclear” (“U”), and “High” (“H”) as a key for judgements. “Low” indicated a low risk of bias, “Unclear” indicated that the risk of bias was uncertain, and “High” indicated a high risk of bias. Disagreements were resolved by discussion among the 3 reviewers and an arbiter, Park KS.

2.7. Data synthesis

In our review, for studies using the same type of acupuncture, comparator, and outcome measures, the meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager software (RevMan v. 5.3). To assess the effect of acupuncture on primary dysmenorrhea, dichotomous data were analyzed using a risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and continuous data were analyzed using mean differences (MD) and 95% CIs or standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% CIs if different scales were used. The chi-square and I2 tests were used to assess statistical heterogeneity.[20] If I2 > 50% or P < .1, we considered that there was substantial heterogeneity among the trials, and if I2 > 75%, we considered that there was serious heterogeneity. When serious heterogeneity was indicated, we found sources of heterogeneity by subgroup or sensitivity analysis. Subgroup analysis was conducted according to the treatment periods, and sensitivity analysis was done by excluding each heterogeneous trial. In case of substantial heterogeneity, a random effects model was used; otherwise, a fixed effects model was used to synthesize the data. However, if there were few studies for pooling, a fixed effects model was implemented because it is difficult to obtain a precise estimate of the between-studies variance.[21] If the number of the appropriate studies was only 1, or data were unsuitable for quantitative synthesis, descriptive synthesis of the findings was performed. If the number of studies for pooling was more than 10, publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot.[22]

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

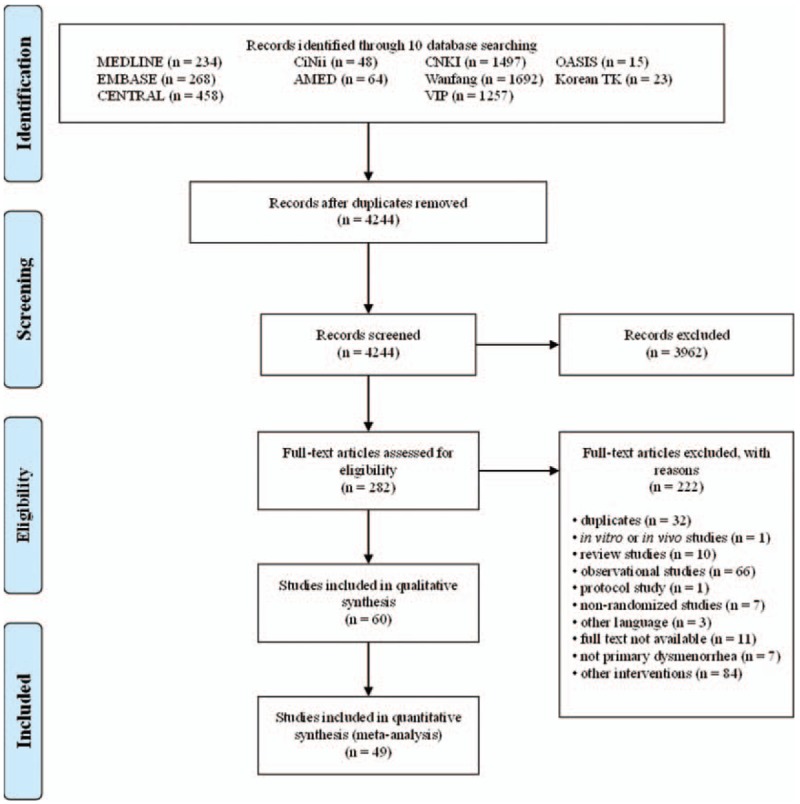

A total of 4244 articles were screened, and 3962 were retrieved. The full texts of 282 studies were reviewed; 222 did not meet our inclusion criteria. Finally, 60 RCTs meeting our criteria were included. All studies were published between January 1987[23] and November 2017.[24] Forty-four studies were published in Chinese,[24–67] 15 in English,[11,23,68–80] and 1 in Korean.[81]Figure 1 shows a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow of the study selection process.[82]

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the study selection process used for meta-analysis. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses.

3.2. Study characteristics

3.2.1. Patients

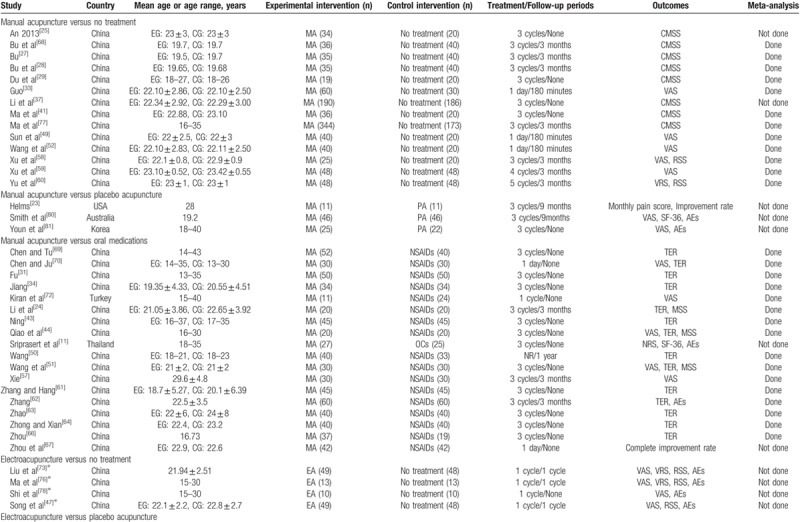

A total of 3171 patients were treated with MA, EA, warm acupuncture (WA), AA, or catgut embedding therapy (CET); 2730 control patients received no treatment, placebo acupuncture, or oral medications. Of 60 trials, 55 were conducted in China (5653 patients),[24–71,73–79] and 1 each was conducted in America (22 patients),[23] Turkey (35 patients),[72] Australia (92 patients),[80] Thailand (52 patients),[11] and South Korea (47 patients),[81] respectively. The age range of the participants was 10 to 43 years. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1.

Summary of the included studies.

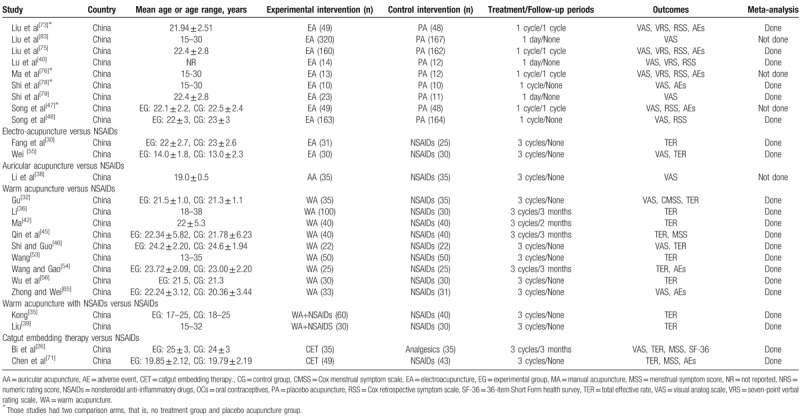

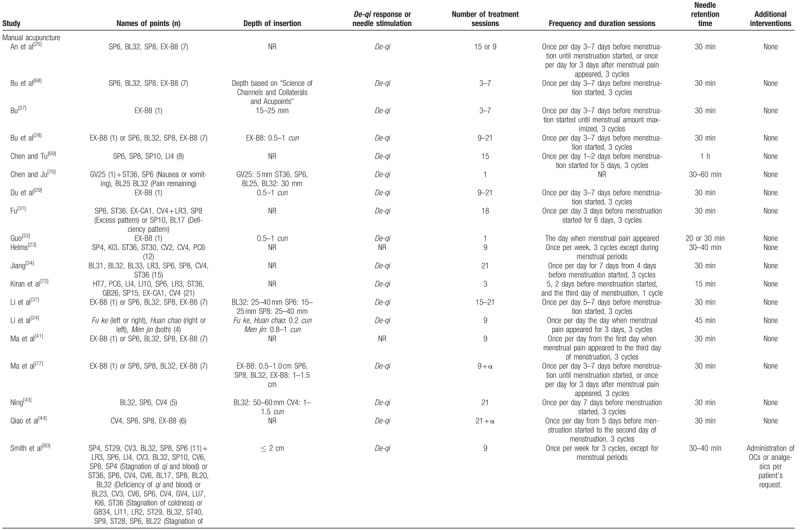

3.2.2. Acupuncture interventions

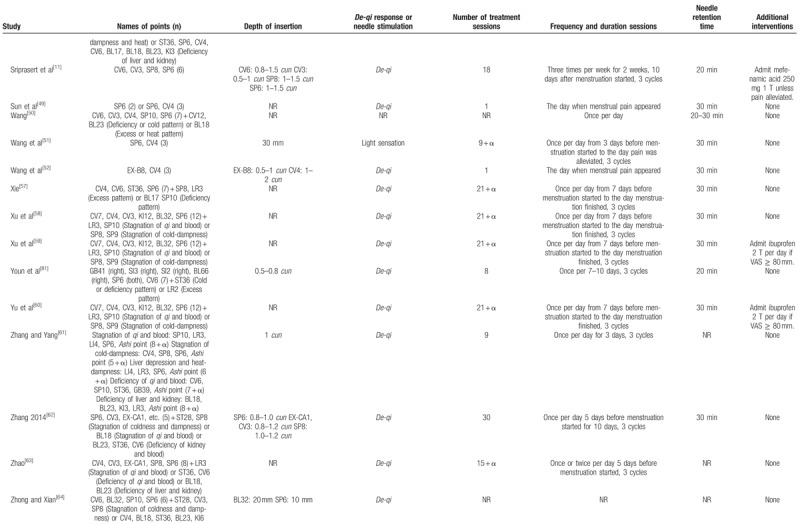

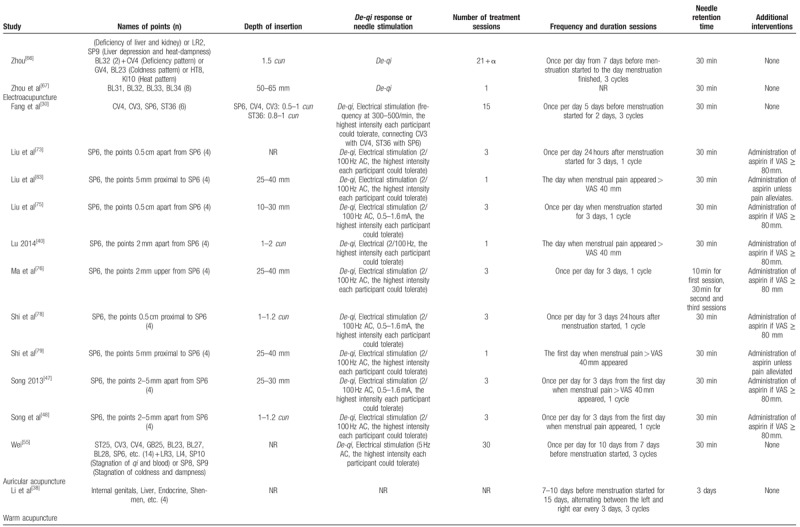

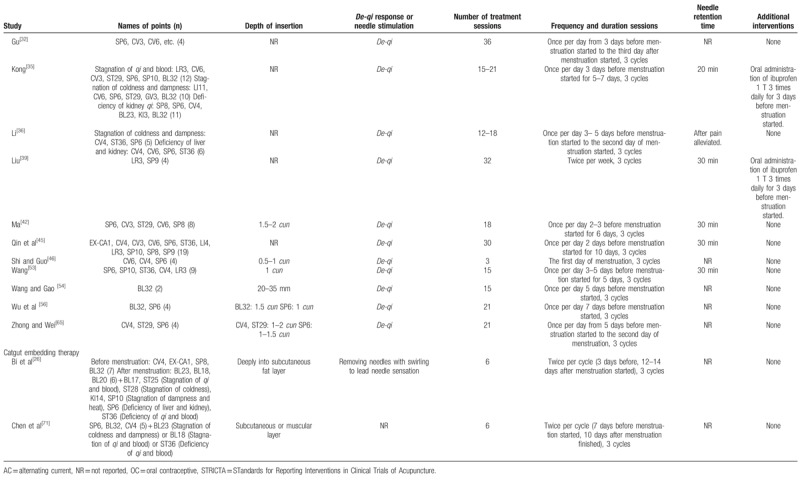

Of 60 trials, 35 used MA,[11,23–25,27–29,31,33,34,37,41,43,44,49–52,57–64,66–70,72,77,80,81] 11 used EA,[30,40,47,48,55,73–76,78,79] 11 used WA,[32,35,36,39,42,45,46,53,54,56,65] 1 used AA,[38] and 2 used CET.[26,71] The number of acupoints used varied from 1 to 21. The most frequently used point was Sanyinjiao (SP6), followed by Guanyuan (CV4), Diji (SP8), Cialiao (BL32), Zusanli (ST36), Xuehai (SP10), Taichong (LR3), Zhongji (CV3), Shiqizhui (EX-B8), and Shenshu (BL23). The only point used in 9 trials that used EA was Sanyinjiao (SP6). Twenty-one trials used different acupoints or added acupoints based on traditional Chinese medicine patterns.[26,31,35,36,50,55,57–60,62–64,66,70,71,80,81] Treatment duration ranged from one day to 3 menstrual cycles; 25 trials included follow-ups,[23,24,26–28,33,36,42,45,47,49,50,52,54,57–60,62,68,73,75–77,80] which varied from 180 minutes to one year. The time of intervention started before menstruation started in 31 trials,[27–32,34–38,42–45,51,53–60,62,63,65,66,68,69,72] when menstruation started in 4 trials,[46,73,75,78] when pain occurred in 10 trials,[24,33,40,41,47–49,52,74,79] and continuous treatment except for menstrual periods in 6 trials.[11,23,26,39,71,80]De-qi sensation was performed in most trials, but 4 studies did not mention about De-qi sensation.[23,38,41,50] Additional interventions to acupuncture were included in 15 trials.[11,35,39,40,47,48,59,60,73–76,78–80]Table 2 shows the acupuncture points and treatment methods of the included studies based on STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) recommendations.[84]

Table 1 (Continued).

Summary of the included studies.

Table 2.

Acupuncture interventions of the included studies based on STRICTA recommendations.

Table 2 (Continued).

Acupuncture interventions of the included studies based on STRICTA recommendations.

Table 2 (Continued).

Acupuncture interventions of the included studies based on STRICTA recommendations.

Table 2 (Continued).

Acupuncture interventions of the included studies based on STRICTA recommendations.

3.2.3. Control interventions

Of the 35 trials that used MA, 14 compared MA to no treatment,[25,27–29,33,37,41,49,52,58–60,68,77] 3 compared MA to placebo acupuncture,[23,80,81] and 18 compared MA to oral medications.[11,24,31,34,43,44,50,51,57,61–64,66,67,69,70,72] Most of the medications were NSAIDs, and only 1 was an OC.[11] Of the 11 trials that used EA, 4 compared EA to nonacupoint EA (placebo EA), or no treatment,[47,73,76,78] 5 compared EA to nonacupoint EA,[40,48,74,75,79] and 2 compared EA to NSAIDs.[30,55] Of 11 trials that used WA,[32,35,36,39,42,45,46,53,54,56,65] 2 trials compared WA plus NSAIDs to NSAIDs[35,39] and 9 trials compared WA to NSAIDs.[32,35,36,39,42,45,46,53,54,56,65] One trial compared AA to NSAIDs.[38] Two trials compared CET to NSAIDs.[26,71] All of the placebo controls used nonacupoint acupuncture, not sham acupuncture.

3.2.4. Outcome measures

Twenty-seven trials measured pain intensity using VAS,[26,32,33,38–40,44,46–49,51,52,55,57–59,65,70,72–76,78,79,81] 1 used NRS,[11] 9 used CMSS,[25,27–29,32,37,41,68,77] 5 used VRS,[40,60,73,75,76] and 8 used RSS.[40,47,48,58,60,73,75,76] Thirty trials measured pain relief.[23,24,26,30–32,34–36,39,42–46,50,51,53–56,61–64,66,67,69–71] Six trials measured overall menstruation symptoms using MSS.[24,26,44,45,51,71] Three trials measured the quality of life using SF-36.[11,26,80] Twelve trials reported AEs.[11,47,54,62,65,71,73,75,76,78,80,81] Finally, of 25 trials conducting follow-ups, 10 trials reported the pain intensity after a follow-up period,[23,26,33,49,52,57–59,75,80],which varied from 180 minutes to 9 months by study. Most studies reported various outcomes measuring dysmenorrhea and related symptoms.

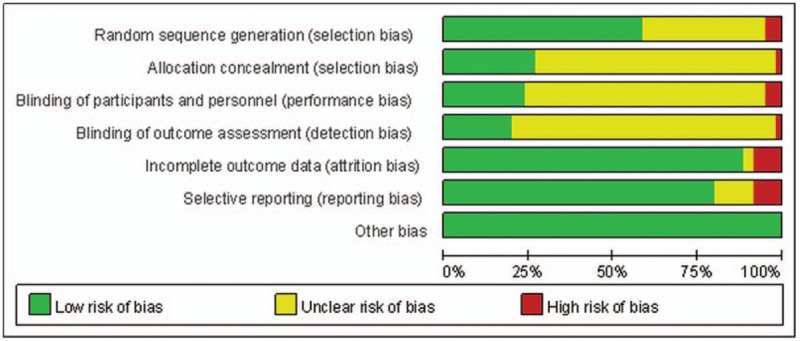

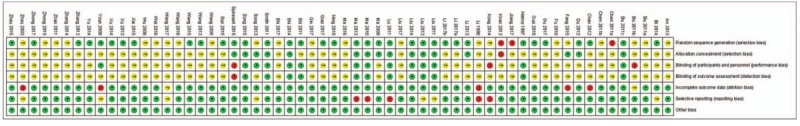

3.3. Risk of bias

All 60 studies mentioned randomization. Twenty trials used random number tables,[23,24,26,33,38,43,44,49,51,52,54,57–61,65,67,71,81] 10 used a computer-generated sequence,[11,48,73–80] 5 used central random method,[28,29,37,40,41] and 1 used the draw method.[32] Three trials used the order of joining the study,[34,69,72] and the other studies did not report the details of randomization. Sixteen studies reported appropriate allocation concealment[11,28–30,37,40,41,47,48,73–77,79,80] using computer programs, central telephone controls, sealed envelopes, or independent individual controls.

It is difficult to achieve blinding to both participants and practitioners for the characteristics of study design in acupuncture intervention, but 14 studies mentioned efforts to minimize performance bias,[23,28,40,47,48,73–81] so we assessed the risk of bias as low. Twelve studies reported assessor blinding,[23,28,40,48,73–80] but most of the others did not report the details.

Most of the studies had no missing data, performed intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, or had similar numbers and reasons of drop-outs. However, the details of drop-outs and withdrawals were not reported in 6 studies,[27,30,36,66,71,81] considered to be a high risk in reporting bias. Forty-nine studies reported all outcomes clearly as mentioned in protocol studies or methods[11,23–25,27–34,37–39,41–46,48–65,67–72,75,78–80] and were assessed as a low risk of bias in selective reporting. Six studies reported the outcomes unclearly[26,47,66,73,74,81] and were assessed as an unclear risk of bias, and 5 studies did not report all outcomes as planned[35,36,40,76,77] and were assessed as a high risk of bias. There was a low risk of other sources of bias based on lack of clear evidence. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, most of the studies included in this meta-analysis achieved a low or unclear risk of bias of the quality assessment items.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review of the authors’ judgments regarding each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review of the authors’ judgments regarding each risk of bias item in each included study.

3.4. Data synthesis

3.4.1. Manual acupuncture

3.4.1.1. MA versus no treatment

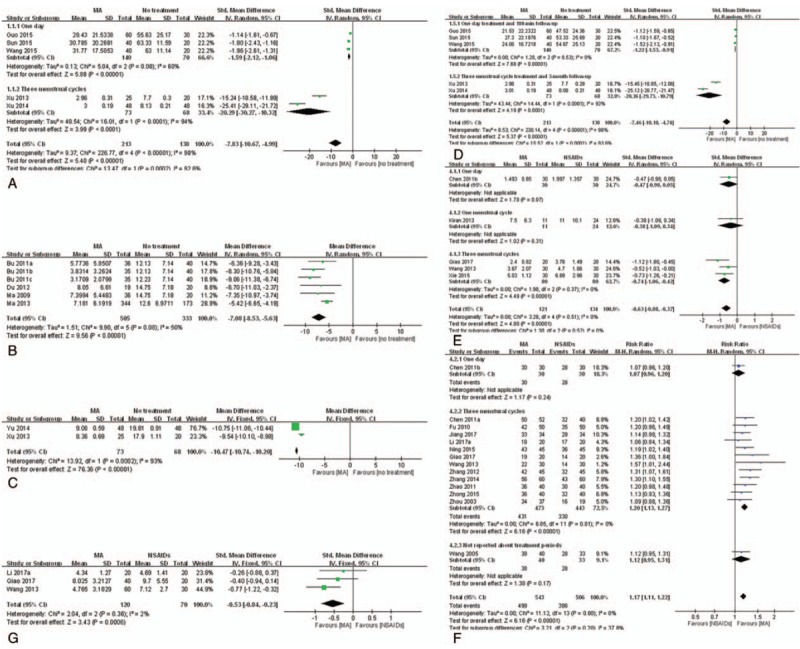

VAS. Five studies[33,49,52,58,59] were included in the meta-analysis to synthesize VAS data. As shown in Figure 4A, the pooled results showed serious heterogeneity (I2 = 98%). We conducted a subgroup analysis, and the pooled results showed that after treatment of 1 day, MA more effectively reduced primary dysmenorrhea than no treatment (n = 210, SMD = −1.59, 95% CI [−2.12, −1.06], P < .001, I2 = 60%).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of the studies evaluating the effects of MA on primary dysmenorrhea. (A) MA vs no treatment, outcome: VAS. (B) MA vs no treatment, outcome: CMSS for pain intensity. (C) MA vs no treatment, outcome: RSS. (D) MA vs no treatment, outcome: VAS after follow-up. (E) MA vs NSAIDs, outcome: VAS. (F) MA vs NSAIDs, outcome: TER. (G) MA vs NSAIDs, outcome: MSS. CMSS = Cox menstrual symptom scale, MA = manual acupuncture, NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, MSS = menstrual symptom score, RSS = Cox retrospective symptom scale, TER = total effective rate, VAS = visual analog scale.

VRS. One study[60] reported that after the treatment of 3 menstrual cycles, MA more effectively reduced primary dysmenorrhea than no treatment (n = 96, MD = −2.04, 95% CI [−2.11, −1.97], P < .001).

CMSS for pain intensity. Six studies[27–29,41,68,77] were included in the meta-analysis to synthesize CMSS for pain intensity data. As shown in Figure 4B, after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles, MA more effectively reduced pain than no treatment (n = 838, MD = −7.08, 95% CI [−8.53, −5.63], P < .001, I2 = 50%). Two studies[25,37] reported the subscales of CMSS for pain intensity; 1 study[25] reported the MA significantly reduced abdominal pain, and the other[37] reported that the MA significantly reduced extra bed time.

RSS. Two studies[58,60] were included for meta-analysis to synthesize RSS data. As shown in Figure 4C, after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles, MA more effectively reduced pain than no treatment (n = 141, MD = −10.47, 95% CI [−10.74, −10.20], P < .001, I2 = 93%).

VAS after follow-up. Five studies[33,49,52,58,59] were included for meta-analysis to synthesize VAS after follow-up data. As shown in Figure 4D, the pooled results showed serious heterogeneity (I2 = 98%). We conducted a subgroup analysis, and after a 180-minute follow-up, MA was significantly more effective than no treatment (n = 210, SMD = −1.22, 95% CI [−1.53, −0.91], P < .001, I2 = 0%).

3.4.1.2. MA versus placebo acupuncture

Pain intensity. Three studies reported pain scores,[23,80,81] but data were unsuitable for pooling because the score systems of the studies were different from each other. One study[23] reported that MA lowered monthly pain score after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles (n = 22, MD = −70.67, 95% CI [−126.52, −14.82], P = .01) and another study[80] reported that MA lowered the pain score after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles without significant differences (n = 92, MD = −0.7, 95% CI [−1.8, 0.4], P = .21). The other study[81] also reported that there were no significant differences between groups after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles (n = 47).

Pain relief. One study[23] reported that after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles, MA provided a significant improvement in pain compared to placebo acupuncture (n = 22, RR = 2.50, 95% CI [1.12, 5.58], P < .05).

SF-36. One study[80] reported that after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles, there was no significant difference in all SF-36 subscales or both component scores between the 2 groups (n = 92, bodily pain MD = −6.1, 95% CI [−15.1, 2.8], P = .18; General health MD = 5.1, 95% CI [−3.0, 13.2], P = .22; Vitality MD = 3.2, 95% CI [−5.1, 11.6], P = .44; Social function MD = 1.1, 95% CI [−8.0, 10.3], P = .81; Role emotional MD = 2.2, 95% CI [−12.7, 17.1], P = .77; Mental health MD = 6.0, 95% CI [−1.7, 13.6], P = .13; Overall Physical Component MD = −2.3, 95% CI [−5.9, 1.2], P = .19; Overall Mental Component MD = 3.5, 95% CI [−1.1, 8.1], P = .71).

Pain intensity after follow-up. Two studies[23,80] reported this outcome. One study[23] reported MA maintained pain reduction until 9 months after the completion of treatment (n = 22, MD = −64.90, 95% CI [−122.11, −7.69], P = .03). The other[80] reported there were no significant differences between the groups after 3- and 9-month follow-up periods.

3.4.1.3. MA versus oral medications

Pain intensity. Five studies[44,51,57,70,72] comparing MA to NSAIDs reported VAS, and 1 study[11] comparing MA to OCs reported a change in NRS. As shown in Figure 4E, the MA was significantly more effective at reducing pain than NSAIDs (n = 255, SMD = −0.63, 95% CI [−0.88, −0.37], P < .001, I2 = 0%). Meanwhile, OCs were more effective than MA after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles (n = 52, MD = 1.58, 95% CI [0.36, 2.80], P < .01).

Pain relief. Fourteen studies[24,31,34,43,44,50,51,61–64,66,69,70] comparing MA to NSAIDs were included for meta-analysis to synthesize TER data. As shown in Figure 4F, MA provided significant pain relief compared to NSAIDs (n = 1,049, RR = 1.17, 95% CI [1.11, 1.22], P < .001, I2 = 0%). The funnel plot of those studies did not show asymmetry. One study[67] reported pain relief as percentage using 6-Likert score, and also showed significant pain relief compared to NSAIDs (n = 84, RR = 2.97, 95% CI [1.75, 5.05], P < .01).

MSS. Three studies[24,44,51] comparing MA to NSAIDs reported MSS. As shown in Figure 4G, MA was significantly more effective at improving menstrual symptoms than NSAIDs after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles (n = 190, SMD = −0.53, 95% CI [−0.84, −0.23], P < .001, I2 = 2%).

SF-36. One study[11] reported that there was no significance difference between the 2 groups after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles (n = 52, MD = −1.82, 95% CI [−9.36, 5.72], P = .64).

VAS after follow-up. One study[57] reported that after a 3-month follow-up, MA was significantly more effective than NSAIDs (n = 60, MD = −1.39, 95% CI [−2.65, −0.13], P < .05).

AEs. Two studies[11,62] reported AEs. One study[11] reported one case of regional discomfort or hemorrhage, 4 cases of headache or myalgia, and 1 case of fever in the MA group, which were all mild. Meanwhile, in the OCs group[11], 9 cases of abnormal uterine bleeding, 5 cases of headache or myalgia, 3 cases of weight gain, 2 cases of nausea or vomiting, and 1 case of breast bleeding were reported; they were all already known AEs of OCs and were not severe. The other study[62] reported 3 cases of elevated alanine transaminase (ALT), 2 cases of blurred vision, 3 cases of lumbar and leg pain, and 5 cases of others, which were predictable reactions, and soon disappeared.

3.4.2. Electroacupuncture

3.4.2.1. EA versus no treatment

VAS. Four studies[47,73,76,78] reported that EA was significantly more effective at reducing pain than no treatment (n = 97, MD = −15.56, 95% CI [−22.16, −8.95], P < .001[73]; n = 26, MD = −23.19, 95% CI [−32.06, −14.33], P < .001[76]; n = 20, MD = −22.50, 95% CI [−31.70, −13.30], P < .005[78]; n = 97, P < .001; details of data not shown[47]). Data were unsuitable for pooling for means and SDs were not reported.

VRS. Two studies[73,76] reported that there was no significant difference between the groups. Data were unsuitable for pooling because they reported the results only in graphs, which made it hard to extract raw data.

RSS. Three studies[47,73,76] reported this outcome. Two studies[73,76] showed there was no significant difference in RSS, but the other study[47] showed that EA was significantly more effective than no treatment in RSS-COX2 (P < .05). Data were unsuitable for pooling because they reported the results only as graphs, which made it hard to extract raw data.

AEs. Four studies[47,73,76,78] reported AEs, but 1study[73] showed 1 case of dizziness after EA.

3.4.2.2. EA versus placebo acupuncture

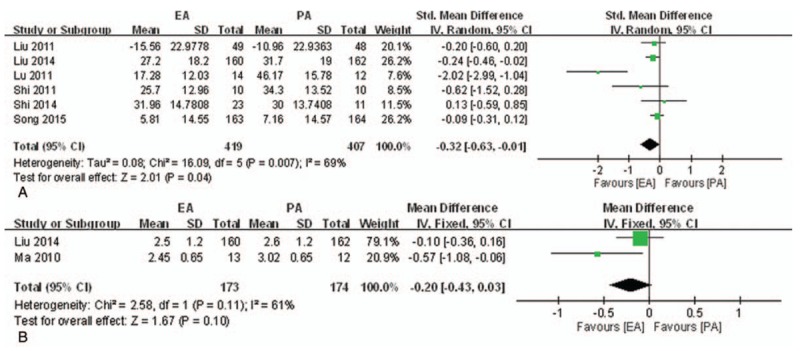

VAS. Nine studies[40,47,48,73–76,78,79] reported this outcome; only 6 studies[40,48,73,75,78,79] were included in the meta-analysis because the other 3 did not provide SDs. As shown in Figure 5A, the VAS of the EA group was significantly lower than placebo group (n = 826, SMD = −0.32, 95% CI [−0.63, −0.01], P = .04, I2 = 69%). Of the 3 studies excluded from meta-analysis[47,74,76], 1 study[74] reported that EA was significantly more effective in reducing pain than the placebo group in cold-dampness stagnation after one session of treatment (n = 487, MD = −8.2, 95% CI [−13.5, −2.9], P < .005); in other types, there was no significant difference. Another study[76] showed the same result after treatment of 1 menstrual cycle (n = 25, MD = −20.78, 95% CI [−29.82, −11.73], P < .001). The other RCT[47] reported that there was no significant difference between the groups after treatment of 1 menstrual cycle (n = 97, details of data not shown).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of the studies evaluating the effects of EA on primary dysmenorrhea. (A) EA versus PA, outcome: VAS. (B) EA versus PA, outcome: VRS. (C) EA versus NSAIDs, outcome: TER. EA = electroacupuncture, IV = inverse variance, NSAIDs = nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs, NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, PA = placebo acupuncture, SD = standard deviations, TER = total effective rate, VAS = visual analog scale, VRS = seven-point verbal rating scale.

VRS. Three studies[73,75,76] reported VRS, but only 2[75,76] were included in the meta-analysis because the third did not provide SDs. As shown in Figure 5B, after treatment of 1 menstrual cycle, the VRS in the EA group was lower than the placebo group, but there was no significance (n = 347, MD = −0.20, 95% CI [−0.43, 0.03], P = .10, I2 = 61%). The other study[73] also reported a change of VRS in the EA group that was lower than the placebo group, but there was no significance (n = 322, reduction from 3.94 to 3.08 vs reduction 3.72 to 3.02).

RSS. Four studies[47,73,75,76] reported RSS, but the data were unsuitable for pooling due to insufficient reporting. One study[73] reported there was no significant difference between the groups (RSS-COX1: reduction from 18.98 to 18.38 vs reduction from 19.44 to 20.20; RSS-COX2: reduction from 11.88 to 11.38 vs reduction from 10.22 to 10.51), and another study[75] showed no significance after 3 cycles, either (n = 97, RSS-COX1 MD = −0.8, 95% CI [−2.2, 0.7], P = .28; RSS-COX2 MD = −0.5, 95% CI [−1.4, 0.4], P = .28). The other 2 studies[47,76] also showed no significance in RSS (data not shown).

VAS after follow-up. One study[75] reported that after one-cycle follow-up, there were no significance differences between EA and PA groups (n = 322, MD = −4.40, 95% CI [−9.55, 0.75], P = .09).

AEs. Five studies[47,73,75,76,78] reported AEs. Three studies[47,76,78] reported there were no AEs, and one[73] of the other studies reported one case of dizziness after EA. The other study[75] reported one case of minimal bleeding in the EA group, and one case of minimal bleeding and one case of pain after insertion in the placebo group.

3.4.2.3. EA versus NSAIDs

VAS. One study[55] reported that after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles, EA was significantly effective at reducing pain than NSAIDs (n = 60, MD = −1.40, 95% CI [−2.21, −0.59], P < .01).

Pain relief. Two studies[30,55] reported TER, but as shown in Figure 5C, the pooled results showed no significant differences between 2 groups (n = 140, RR = 1.80, 95% CI [0.99, 1.18], P = .09, I2 = 0%).

3.4.3. Auricular acupuncture

3.4.3.1. AA versus NSAIDs

VAS. One study[38] reported that after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups (n = 70, MD = −0.20, 95% CI [−0.90, −0.50], P = .58).

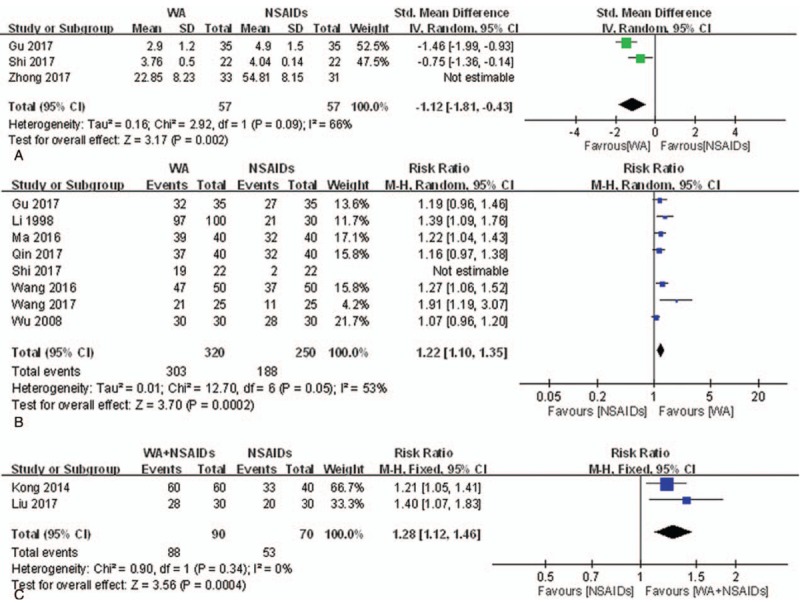

3.4.4. Warm acupuncture

3.4.4.1. WA versus NSAIDs

VAS. Three studies[32,46,65] were included in the meta-analysis to synthesize VAS data. A meta-analysis of the 3 studies involving 178 participants was implemented, but the results showed serious heterogeneity (I2 = 94%). We conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding the trial[65] with effect sizes largely different from the others. Statistical heterogeneity was reduced after exclusion. As shown in Figure 6A, with 2 remaining studies, the VAS of the WA group was significantly lower than NSAIDs group (n = 114, SMD = −1.12, 95% CI [−1.81, −0.43], P = .002, I2 = 66%).

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis of the studies evaluating the effects of WA on primary dysmenorrhea. (A) WA vs NSAIDs, outcome: VAS. (B) WA vs NSAIDs, outcome: TER. (C) WA plus NSAIDs vs NSAIDs, outcome: TER. CI = confidence interval, IV = inverse variance, NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SD = standard deviations, TER = total effective rate, VAS = visual analog scale, WA = warm acupuncture.

TER. Eight studies[32,36,42,45,46,53,54,56] were included in the meta-analysis to synthesize TER data. A meta-analysis of the 3 studies involving 614 participants was implemented, but the results showed serious heterogeneity (I2 = 77%). We conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding the trial[46] with effect sizes largely different from the others. As shown in Figure 6B, with 6 remaining studies, the WA provided significant pain relief compared to NSAIDs after the treatment of 3 menstrual cycles (n = 570, RR = 1.22, 95% CI [1.10, 1.35], P < .001, I2 = 53%).

CMSS for pain intensity. One study[32] reported that after the treatment of 3 menstrual cycles, WA more effectively reduced primary dysmenorrhea than NSAIDs (n = 70, MD = −8.00, 95% CI [−9.54, −6.46], P < .001).

MSS. One study[45] reported that there were no significant differences between WA and NSAIDs groups (n = 80, MD = −1.09, 95% CI [−2.65, −0.47], P = .17).

AEs. Two studies[54,65] reported AEs. One study[54] reported 5 cases of nausea, vomiting, and fever in the NSAIDs group, and the other study[65] reported there were no AEs.

3.4.4.2. WA plus NSAIDs versus NSAIDs

TER. Two studies[35,39] reported that WA adding on NSAIDs provided significant pain relief compared to only NSAIDs after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles (n = 160, RR = 1.28, 95% CI [1.12, 1.46], P < .001, I2 = 0%).

3.4.5. Catgut embedding therapy

3.4.5.1. CET versus NSAIDs

VAS. One study[26] reported that CET was significantly more effective than NSAIDs after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles (n = 70, t = −2.70, P < .01).

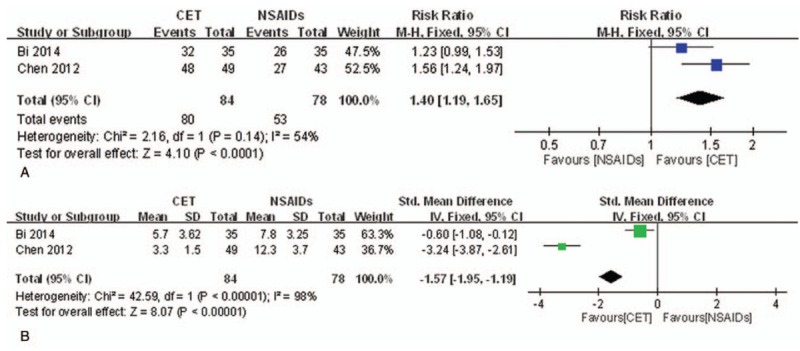

TER. Two studies[26,71] reported that CET provided significant pain relief compared to NSAIDs after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles as shown in Figure 7A (n = 162, RR = 1.40, 95% CI [1.19, 1.65], P < .001, I2 = 54%).

Figure 7.

Meta-analysis of the studies evaluating the effects of CET on primary dysmenorrhea. (A) CET vs NSAIDs, outcome: TER. (B) CET vs NSAIDs, outcome: MSS. CET = catgut embedding therapy, CI = confidence interval, IV = inverse variance, MSS = menstrual symptom score, NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SD = standard deviations, TER = total effective rate.

MSS. Two studies[26,71] reported that CET effectively reduced menstrual symptoms compared to NSAIDs after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles with serious heterogeneity as shown in Figure 7B (n = 162, SMD = −1.57, 95% CI [−1.95, −1.19], P < .001, I2 = 98%).

SF-36. One study[26] reported that SF-36 in the CET group was significantly higher than the NSAIDs group after treatment of 3 menstrual cycles (n = 70, t = 2.535, P < .05).

VAS after follow-up. One study[26] reported that after a 3-month follow-up, CET was significantly more effective than NSAIDs (n = 70, t = −4.72, P < .01).

AEs. One study[71] reported 6 cases of gastrointestinal discomforts, headache, dizziness, and insomnia in the NSAIDs group.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the main results

This systematic review was aimed to summarize and evaluate acupuncture treatment to reduce menstrual pain and its associated symptoms. As a result, we suggest that acupuncture might have beneficial effects for improvement of dysmenorrhea and remain efficacious after short-term follow-up.

We conducted comparisons separately according to the characteristics of interventions and controls. MA was significantly more effective than no treatment, and NSAIDs for reduction of menstrual pain and its associated symptoms, and remained effective after a short-term follow-up compared to no treatment and NSAIDs. The MA-induced analgesic effect could be explained by C-fiber involvement during the practitioners’ manipulation for the de-qi response.[85] However, no significant difference was observed between MA and placebo acupuncture or between MA and OCs. It was difficult to determine the superior effect of OCs compared to MA because there was only one relevant study.[11]

The results showed that EA was significantly more effective at reducing menstrual pain than no treatment,[47,73,76,78] placebo acupuncture,[40,48,73–76,78,79] but not effective at improving its associated symptoms.[47,73,75,76] The results comparing with NSAIDs were insufficient to determine the efficacy of EA. The mechanism of EA-induced analgesia could be explained by inducing the release of endorphins[86,87] and the decrease of the pulsatility index in the uterine arteries,[88] which might be related to primary dysmenorrhea.[1] The reason that there was no difference between MA and placebo acupuncture and the relatively small difference between EA and placebo acupuncture was thought to be that placebo acupuncture also had positive effects. Several factors might explain the positive effects. First, some participants receiving placebo acupuncture may want pain relief, and it may affect the outcome psychologically.[89] Second, placebo acupuncture may stimulate cutaneous touch receptors and/or skin nociceptors and modulate the activity in the brain areas associated with pain management.[90]

WA was significantly more effective at reducing menstrual pain than NSAIDs, but the efficacy for the associated symptoms was inconclusive due to the small sample size. The results showed WA with NSAIDs might also relieve menstrual pain compared to NSAIDs alone. WA increases the circulation of qi and blood through the needle body during thermal heating. It provides analgesic effects by stimulating nerve transfer and relaxing uterine muscle spasms.[91]

CET might also be effective for primary dysmenorrhea. CET is a therapeutic modality based on acupuncture theory and continuous stimulation of acupoints with embedded thread, and its continuous stimulation prolongs the effects of acupuncture. In addition, the embedded thread gradually liquefies and is absorbed, and stimulates the points physically and chemically.[26] With this mechanism, CET might be considered to demonstrate analgesic effects and maintain the effects for short-term follow-up.

Severe AEs of acupuncture were not observed. Thirteen of the 60 studies reported AEs of acupuncture. Most of the reported AEs were regional pain or discomfort, hematoma, and dizziness. Those mentioned were mild, similar to previously known AEs.[92]

The applicability of acupuncture to primary dysmenorrhea in other settings is unclear. Fifty-seven of the trials were conducted in Asian countries: 55 in China, 1 in Thailand, and 1 in South Korea. The acupuncture practitioners might have different treatment skills according to the nations in which they were trained, and the participants might have different preconceptions and familiarity with acupuncture according their cultures.[89] In addition, the variability of the details of interventions and controls could make applicability unclear.

4.2. Strengths and limitations of this review

Six SRs which evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture on primary dysmenorrhea have previously been conducted,[14–19] and 2 of them were published in 2016[17] and 2017[19], respectively. However, there were some differences between these 2 SRs and our review. They may arise from the different search strategies, inclusion criteria, and analysis methods. In particular, the Cochrane review[17] analyzed 42 studies, just separating the treatment types into acupuncture and acupressure. Liu et al's[19] review analyzed 23 studies with similar strategies to our review, did not include 10 trials newly published in 2017, and did not include other modalities of acupuncture such as WA or CET, frequently used in clinical fields. Our review included all types of acupuncture that stimulate acupoints by penetrating the skin, including CET, and synthesized data separately according to the characteristics of the interventions and controls.

Our study had some limitations, and those results mentioned above should be interpreted with caution. One was that most of the included trials achieved a low or unclear risk of bias. The unclear judgements appeared mostly in the domains of allocation concealment and blinding of participants/practitioners/outcome assessors, because the details were not described. The blinding of participants is critical for subjective outcomes such as pain,[93] but blinding of both participants and practitioners was difficult due to the characteristics of acupuncture intervention. The other limitation was that there was substantial heterogeneity among the pooled trials. We tried to reduce the heterogeneity by synthesizing the data separately depending on the characteristics of the interventions and controls, subgroup analysis, and sensitivity analysis, but the unresolved heterogeneity in some cases still existed. We considered this heterogeneity derived from the small sample sizes in some outcomes and the methodological variations among the included studies. The methods of interventions varied in the frequency, duration of each session, selection of acupoints, and de-qi methods. The variations of controls also appeared in different components of NSAIDs. These variations could influence the results of the trials, and were considered to cause unresolved heterogeneity.

4.3. Implications of this review for practice and research

To provide convincing evidence of the efficacy of acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhea, future RCTs should adhere to rigorous standards assessing the risk of bias, such as conducting randomization allocation concealment and trying to avoid performance bias. In addition, those trials should be reported as STRICTA guidelines[84] to clear the specific method of each intervention.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that acupuncture might reduce menstrual pain and associated symptoms more effectively compared with no treatment or NSAIDs, and the efficacy could be maintained during a short-term follow-up period. However, the efficacy of acupuncture compared to a placebo was not convincing. The safety of acupuncture appeared because a few mild AEs were reported. Our suggestions had limitations because the quality of the included RCTs was low, and methodological restriction existed in this study. More rigorously designed trials are required to confirm our findings.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Hye Lin Woo, Hae Ri Ji, Yeon Kyoung Pak, Jin Moo Lee, Kyoung Sun Park.

Data curation: Hye Lin Woo, Yeon Kyoung Pak, Hojung Lee, Su Jeong Heo.

Formal analysis: Hye Lin Woo.

Funding acquisition: Jin Moo Lee.

Methodology: Hye Lin Woo, Hae Ri Ji, Yeon Kyoung Pak, Hojung Lee, Su Jeong Heo, Kyoung Sun Park.

Project administration: Jin Moo Lee, Kyoung Sun Park.

Writing – original draft: Hye Lin Woo.

Writing – review & editing: Kyoung Sun Park.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AA = auricular acupuncture, AE = adverse event, CET = catgut embedding therapy, CI = confidence interval, CMSS = Cox menstrual symptom scale, EA = electroacupuncture, MA = manual acupuncture, MD = mean difference, MSS = menstrual symptom score, NRS = numeric rating score, NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, OC = oral contraceptive, PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses, RCT = randomized controlled trial, RR = risk ratio, RSS = Cox retrospective symptom scale, SD = standard deviations, SF-36 = 36-item short form health survey, SMD = standardized mean difference, SR = systematic review, STRICTA = STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture, TER = total effective rate, VAS = visual analog scale, VRS = seven-point verbal rating scale, WA = warm acupuncture.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was not required for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

This study was supported by the Traditional Korean Medicine R&D Program funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) (HB16C0018).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhea: advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:428–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Weissman AM, Hartz AJ, Hansen MD, et al. The natural history of primary dysmenorrhoea: a longitudinal study. BJOG 2004;111:345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hillen TI, Grbavac SL, Johnston PJ, et al. Primary dysmenorrhea in young Western Australian women: prevalence, impact, and knowledge of treatment. J Adolesc Health 1999;25:40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ng TP, Tan NC, Wansaicheong GK. A prevalence study of dysmenorrhoea in female residents aged 15-54 years in Clementi Town, Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1992;21:323–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Harlow SD, Park M. A longitudinal study of risk factors for the occurrence, duration and severity of menstrual cramps in a cohort of college women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:1134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wilson CA, Keye WR., Jr A survey of adolescent dysmenorrhea and premenstrual symptom frequency. A model program for prevention, detection, and treatment. J Adolesc Health Care 1989;10:317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lefebvre G, Pinsonneault O, Antao V, et al. Primary dysmenorrhea consensus guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2005;27:1117–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Harel Z. Dysmenorrhea in adolescents and young adults: etiology and management. J Pediat Adolesc Gynecol 2006;19:363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Latthe PM, Champaneria R. Dysmenorrhoea. BMJ Clin Evid 2014;2014:0813. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wong CL, Farquhar C, Roberts H, et al. Oral contraceptive pill as treatment for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD002120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sriprasert I, Suerungruang S, Athilarp P, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture versus combined oral contraceptive pill in treatment of moderate-to-severe dysmenorrhea: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015;2015:735690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].White A, Medicine EBoAi. Western medical acupuncture: a definition. Acupunct Med 2009;27:33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhao ZQ. Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Progr Neurobiol 2008;85:355–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yang H, Liu CZ, Chen X, et al. Systematic review of clinical trials of acupuncture-related therapies for primary dysmenorrhea. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:1114–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chung YC, Chen HH, Yeh ML. Acupoint stimulation intervention for people with primary dysmenorrhea: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Complement Ther Med 2012;20:353–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Smith CA, Zhu X, He L, et al. Acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;4:Cd007854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Smith CA, Armour M, Zhu X, et al. Acupuncture for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:Cd007854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cho SH, Hwang EW. Acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhoea: a systematic review. BJOG 2010;117:509–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liu T, Yu JN, Cao BY, et al. Acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhea: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Altern Ther Health Med 2017;23:AT5435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].John Wiley & Sons, Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Vol. 4. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, et al. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Helms JM. Acupuncture for the management of primary dysmenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol 1987;69:51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li PJ, Liu WW, Li JS. Clinical observation of 20 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated by Dong Qi acupuncture. Hunan J Tradit Chin Med 2017;33:83–4. [Google Scholar]

- [25].An Y, Du DQ, Gao SZ, et al. Clinical study on different intervention times of acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhea. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibustion 2013;32:91–3. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bi Y, Shao X, Xuan L. Primary dysmenorrhea treated with staging acupoint catgut embedment therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Acupunct Moxibustion 2014;34:115–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bu YQ. Observation on therapeutic effect of acupuncture at Shiqizhui (Extra) for primary dysmenorrhea at different time. Chin Acupunct Moxibustion 2011;31:110–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bu YQ, Hou WJ, Li YM, et al. Observation of the efficacy of acupuncutre at single point and multiple points before menstruation on primary dysmenorrhea. J New Chin Med 2011;43:99–101. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Du DQ, Gao SZ, Ma YX. Clinical research of primary dysmenorrhea with acupuncture at Shiqizhui (EX-B7) before menstruation. World J Integr Tradit West Med 2012;7:1073–5. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fang YJ, Han LB, Wang ZH. Clinical observation of 31 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated by electroacupuncture. Chin J Ethnomed Ethnopharm 2015;24:58–158. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fu L. The clinical observation of the acupuncture treatment for primary dysmenorrheal 50 cases. J Clin Acupunct Moxibustion 2010;26:16–7. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gu LJ. Observation of the clinical efficacy of the combination of chinese and western medicine with warm acupuncture in treating primary dysmenorrhea. China Health Care Nutrit 2017;9:392–3. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Guo ZP. Study of analgesic effect of acupuncture on Shinqizhui (ex-b8) point with different needle retaining time on primary dysmenorrhea. J Shandong Univ TCM 2015;39:322–4. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jiang LY. Clinical experience of 34 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated with acupuncture. J Emerg Tradit Chin Med 2007;16:620–1. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kong Y-X. Observation on curative effect of 60 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated by combination of TCM and Western Medicine. Health World 2014;10:155–6. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li Y. Warm acupuncture for 130 cases of primary dysmenorrhea. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibustion 1998;17:16–7. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li ZF, An Y, Chen SZ, et al. Effect of acupuncture at single point and multiple points on extra bed time and combined use of drugs in patients with primary dysmenorrhea. J Clin Acupunct Moxibustion 2013;29:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Li Z, Qu JH, Wang YZ, et al. Efficacy of press needles to the auricular point in treating primary dysmenorrhea of air force women soldiers. Med J Air Force 2017;33:306–7. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Liu MZ. Observation on the curative effect of traditional chinese medicine acupuncture on primary dysmenorrhea. J Clin Med Lit 2017;4:2413–4. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lu K, Liu Y, Song CD. Efficacy of acupuncture at Sanyinjiao, Xuanzhong, and non-acupoints on primary dysmenorrhea with visual analogue scale. J Changchun Univ Tradit Chin Med 2011;27:375–7. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ma YX, Chen S, Sun YG, et al. Clinical study of primary dysmenorrhea treated by acupuncture at single point and multiple points. Shandong J Tradit Chin Med 2009;28:711–3. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ma HY. Clinical analysis of acupuncture treatment of primary dysmenorrhea due to cold coagulation and blood stasis. Chin J Woman Child Health Res 2016;27:207–8. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ning Y. Clinical observation on treating 34 cases of primary dysmenorrhea by acupuncture. Clinical J Chin Med 2015;07:34–5. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Qiao L, Qiao YY, Zhang WD, et al. The optimal selection of the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea by acupuncture and moxibustion. J External Ther Tradit Chin Med 2017;26:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Qin X, Liu ZH, Gao XP, et al. 40 Cases of primary dysmenorrhea of qi stagnation and blood stasis type treated by warm acupuncture. Tradit Chin Med Res 2017;30:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Shi ZH, Guo YJ. Immediate analgesic effect of warming needle moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea. Acta Chin Med 2017;32:1343–6. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Song JS, Liu YQ, Liu CZ, et al. Cumulative analgesic effects of ea stimulation of sanyinjiao (sp 6) in primary dysmenorrhea patients: a multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial. Acupunct Res 2013;38:393–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Song JS, Liu YQ, Liu CZ, et al. Cumulative analgesic effect of electroacupuncture at Sanyinjiao (SP6), Xuanzhong (GB39) and non-acupoint for primary dysmenorrhea. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibustion 2015;34:487–92. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sun MS, Xue Z, Yu YP, et al. Clinical study on the real-time analgesic effect of acupuncture at Sanyinjiao (sp6) versus multiple points for primary dysmenorrhea. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibustion 2015;34:1151–3. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wang CN. Curative effect of acupuncture on 40 cases of dysmenorrhea. J Sichuan Tradit Chin Med 2005;23:84–5. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wang HB, Zhao S, Sun N, et al. Efficacy observation on wrist-ankle needle for primary dysmenorrhea in undergraduates. Chin Acupunct Moxibustion 2013;33:996–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wang H, Zhang X, Yu YP, et al. Comparison of curative effect of acupuncture at Guanyuan and Shiqizhui on primary dysmenorrhea. Shanxi J Tradit Chin Med 2015;31:35–6. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wang RH. Clinical observation of 50 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated by warm acupuncture. World Latest Med Inform (Electronic Version) 2016;16:218+220. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Wang XW, Gao Qq. Efficacy observation on warming-needle moxibustion of eight liao point in treatment of dysmenorrhea with cold coagulation type. J Shandong Univ TCM 2017;41:330–3. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wei N. Clinical observation of 30 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated by Shu-mu combination method. Heilongjiang Med J 2016;40:121–2. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Wu YR, Qiao M, Gao XY. Clinical observation on warming-needle for treatment of primary dysmenorrhea with cold coagulation and blood stasis. Int J Tradit Chin Med 2008;30:363–1363. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Xie J. Observation of therapeutic effect of acupuncture on primary dysmenorrhea. Med Inform 2015;28:265. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Xu SW, Yu C, Zhao JP, et al. Clinical observation on use of pre-acupuncture intervention for primary dysmenorrhea. Chin J Inform Tradit Chin Med 2013;20:76–7. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Xu SW, Yu C, Zhao JP, et al. Effect on primary dysmenorrhea treated by acupuncture. Beijing J Tradit Chin Med 2014;33:41–3. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Yu C, Xu SW, Yang QR, et al. Clinical observations on premenstrual acupuncture for improving symptoms accompanying primary dysmenorrhea. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibustion 2014;33:738–40. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhang LM, Yang HY. 45 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated by simple acupuncture. Fujian J Tradit Chin Med 2012;43:25–6. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Zhang SR. Clinical efficacy of acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Chinese J Clin Rational Drug Use 2014;7:125–6. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zhao ZL. Observation of the curative effect of acupuncture on primary dysmenorrhea. Heilongjiang J Tradit Chin Med 2011;3:46–7. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zhong CY, Xian MF. Observation on the effect of acupuncture and moxibustion on primary dysmenorrhea. Shenzhen J Integr Tradit Chin West Med 2015;25:40–1. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Zhong Y, Wei YL. Warm needling for primary dysmenorrhea of cold-dampness stagnation syndrome. Chin Manipulation Rehab Med 2017;8:32–3. [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zhou LS. Clinical observation on acupuncture Ciliao acupoints for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Hubei J Tradit Chin Med 2003;25:47. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zhou GM, Zhang Y, Shi HC. Clinical analgesic observation of 42 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated by deep needling eight liao acupoints. Zhejiang J Tradit Chin Med 2015;50:380. [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bu YQ, Du GZ, Chen SZ. Clinical study on the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea with preconditioning acupuncture. Chinese J Integrat Med 2011;17:224–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Chen B, Tu X. Acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized controlled trial. J Acupunct Tuina Sci 2011;9:295–7. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Chen ML, Ju YL. Instant effect of acupuncture at Sùliáo (GV 25) mainly for primary dysmenorrhea. World J Acupunct Moxibustion 2011;21:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Chen W, Yu HH, Liu SH, et al. Clinical efficacy observation of primary dysmenorrhea treated with the embedding catgut therapy. World J Acupunct Moxibustion 2012;22:13–7. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Kiran G, Gumusalan Y, Ekerbicer HC, et al. A randomized pilot study of acupuncture treatment for primary dysmenorrhea. European J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013;169:292–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Liu CZ, Xie JP, Wang LP, et al. Immediate analgesia effect of single point acupuncture in primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Med 2011;12:300–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Liu YQ, Ma LX, Xing JM, et al. Does traditional Chinese medicine pattern affect acupoint specific effect? Analysis of data from a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial for primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med 2013;19:43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Liu CZ, Xie JP, Wang LP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of single point acupuncture in primary dysmenorrhea. Pain Med (United States) 2014;15:910–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Ma YX, Ma LX, Liu XL, et al. A Comparative study on the immediate effects of electroacupuncture at Sanyinjiao (SP6), Xuanzhong (GB39) and a non-Meridian point, on menstrual pain and uterine arterial blood flow, in primary dysmenorrhea patients. Pain Med 2010;11:1564–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ma YX, Ye XN, Liu CZ, et al. A clinical trial of acupuncture about time-varying treatment and points selection in primary dysmenorrhea. J Ethnopharmacol 2013;148:498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Shi GX, Liu CZ, Zhu J, et al. Effects of acupuncture at Sanyinjiao (SP6) on prostaglandin levels in primary dysmenorrhea patients. Clin J Pain 2011;27:258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Shi GX, Li QQ, Liu CZ, et al. Effect of acupuncture on Deqi traits and pain intensity in primary dysmenorrhea: Analysis of data from a larger randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Smith CA, Crowther CA, Petrucco O, et al. Acupuncture to treat primary dysmenorrhea in women: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011;2011:Article ID: 612464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Youn HM, Kim CH, Park JH, et al. Effect of acupuncture treatment on the primary dysmenorrhea; a study of single blind, sham acupuncture, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Korean Acupunct Moxibustion Soc 2008;25:139–62. [Google Scholar]

- [82].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Liu XX, Wang X, Deng Y. Efficacy observation on acupuncture combined with auricular point sticking treatment for primary dysmenorrhea. J Acupunct Tuina Sci 2013;11:262–4. [Google Scholar]

- [84].MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, et al. Revised standards for reporting interventions in clinical trials of acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. J Evid Based Med 2010;3:140–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Zhao Z-Q. Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog Neurobiol 2008;85:355–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Ulett GA, Han S, Han JS. Electroacupuncture: mechanisms and clinical application. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Cheng RS, Pomeranz B. Electroacupuncture analgesia could be mediated by at least two pain-relieving mechanisms; endorphin and non-endorphin systems. Life Ssci 1979;25:1957–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Stener-Victorin E, Waldenstrom U, Andersson SA, et al. Reduction of blood flow impedance in the uterine arteries of infertile women with electro-acupuncture. Hum Reprod 1996;11:1314–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Bishop FL, Lewith GT. Patients’ preconceptions of acupuncture: a qualitative study exploring the decisions patients make when seeking acupuncture. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013;13:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Lundeberg T, Lund I, Sing A, et al. Is placebo acupuncture what it is intended to be? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011;2011: 932407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Zhang ZF, Wang HM. 31 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated by acupuncture with moxibustion. Gansu J TCM 2010;23:38–9. [Google Scholar]

- [92].Ernst E, White AR. Prospective studies of the safety of acupuncture: a systematic review. Am J Med 2001;110:481–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.