Surgeons often operate during the night, and often after disturbed sleep or total lack of sleep. Impairment of surgical dexterity due to fatigue could lead to mistakes that are life threatening for the patient. Our study investigated the hypothesis that one night on call in a surgical department would adversely affect the surgeon's performance on simulated laparoscopic tasks.

Participants, methods, and results

The study was carried out in a gastroenterological surgical unit at a teaching hospital. A night shift started at 3 30 pm and finished at 9 am the following day. A total sleep time of less than three hours was necessary for inclusion in the study.

All 14 surgeons in training at our department— 11 men and three women—participated in the study. The median age was 34 (range 24-43) and the median time since graduation was six years (1-11 years). All trainees had similar, limited experience in laparoscopic surgery; the median number of cholecystectomies they had performed was 0 (0-5). All participants received identical pretraining on the minimally invasive surgical trainer-virtual reality (MIST-VR, Mentice Medical Simulation, Gothenburg, Sweden) by performing nine repetitions of six tasks.1,2 The laparoscopic surgical skills of the 14 trainees were assessed on the 10th repetition of the task, which was performed during normal daytime working hours and again at 9 30 am after a night on call with impaired sleep. The period between the first and 10th repetition on the MIST was predetermined to be no longer than one month.

We analysed the data using non-parametric analysis (Wilcoxon test). We examined the difference between scores for error of motion, time of motion, and economy of motion measured during the 10th repetition of the task in the daytime and after a night on call.

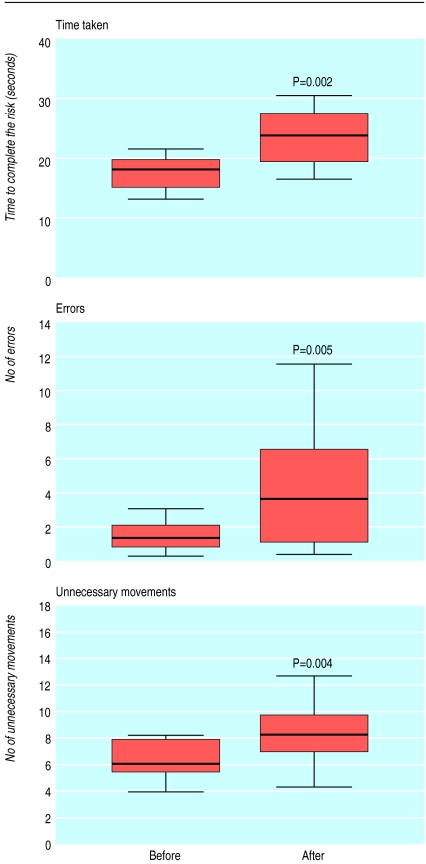

The median total sleep time during the night on call was 1.5 hours (0-3 hours). After a night on call the time taken to complete the virtual laparoscopic tasks (P≤0.006) increased significantly for tasks 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6 (5.4 v 7.6 seconds, 5.6 v 7.8 seconds, 6.7 v 8.1 seconds, 15.0 v 18.1 seconds, and 18.2 v 23.8 seconds, respectively), and after a night shift surgeons performed significantly more errors in tasks 1 and 6 (0.6 v 1.0, P=0.01; and 1.4 v 3.5, P=0.005, respectively). The number of unnecessary movements for tasks 5 and 6 increased significantly after a night on call (7.8 v 9.4, P=0.008 and 6.1 v 8.2, P=0.004, respectively). (Data for all six tasks and a description of each task can be found on the BMJ 's website.) The figure shows data from task 6. This task includes elements from most of the other tasks, is the most complex, and requires the highest levels of concentration and coordination. Previous studies have found that this task correlated best with surgical performance in vivo.3

Comment

Surgeons show impaired speed and accuracy in simulated laparoscopic performance after a night on call in a surgical department. Our results are consistent with the findings of Taffinder et al.4

Previous studies have shown that effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance do not become consistently apparent until after 36-40 hours of total lack of sleep.5 Our results show that significant deficits in psychomotor performance occur after 17 hours on call with disturbed night sleep. Factors connected with surgical work, such as emergency workload, stress, and emotional demands, may potentiate the effects of sleep deprivation alone.

Further studies should determine how long it takes for surgeons' laparoscopic performance to recover after an extended period on duty and should be aimed at developing and evaluating countermeasures that can maximise alertness and reduce fatigue.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Simulated laparoscopic performance of task 6 by surgeons before and after a night on call. Horizontal bands indicate medians, boxes show 25th and 75th centiles, and whisker lines show the highest and lowest values

Footnotes

Funding: Sygekassernes Helsefond, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Competing interests: None declared.

Data for all six tasks can be found on the BMJ's website

References

- 1.Chaudhry A, Sutton C, Wood J, Stone R, McCloy R. Learning rate for laparoscopic surgical skills on MIST VR, a virtual reality simulator: quality of human-computer interface. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1999;81:281–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson MS, Middlebrook A, Sutton C, Stone R, McCloy RF. MIST VR: a virtual reality trainer for laparoscopic surgery assesses performance. Ann Roy Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79:403–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grantcharov TP, Rosenberg J, Pahle E, Funch-Jensen PM. Virtual reality computer simulation—an objective method for evaluation of laparoscopic surgical skills. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:242–244. doi: 10.1007/s004640090008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taffinder NJ, McManus IC, Gul Y, Russell RC, Darzi A. Effect of sleep deprivation on surgeons' dexterity on laparoscopy simulator [letter] Lancet. 1998;352:1191. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koslowsky M, Babkoff H. Meta-analysis of the relationship between total sleep deprivation and performance. Chronobiol Int. 1992;9:132–136. doi: 10.3109/07420529209064524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.