Abstract

Over the past several years, single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged as a leading method for elucidating macromolecular structures at near-atomic resolution, rivaling even the established technique of X-ray crystallography. Cryo-EM is now able to probe proteins as small as hemoglobin (64 kDa), while avoiding the crystallization bottleneck entirely. The remarkable success of cryo-EM has called into question the continuing relevance of X-ray methods, particularly crystallography. To say that the future of structural biology is either cryo-EM or crystallography, however, would be misguided. Crystallography remains better suited to yield precise atomic coordinates of macromolecules under a few hundred kDa in size, while the ability to probe larger, potentially more disordered assemblies is a distinct advantage of cryo-EM. Likewise, crystallography is better equipped to provide high-resolution dynamic information as a function of time, temperature, pressure, and other perturbations, whereas cryo-EM offers increasing insight into conformational and energy landscapes, particularly as algorithms to deconvolute conformational heterogeneity become more advanced. Ultimately, the future of both techniques depends on how their individual strengths are utilized to tackle questions on the frontiers of structural biology. Structure determination is just one piece of a much larger puzzle: a central challenge of modern structural biology is to relate structural information to biological function. In this perspective, we share insight from several leaders in the field and examine the unique and complementary ways in which X-ray methods and cryo-EM can shape the future of structural biology.

Keywords: crystallography, cryo-EM, resolution, structural biology

Introduction

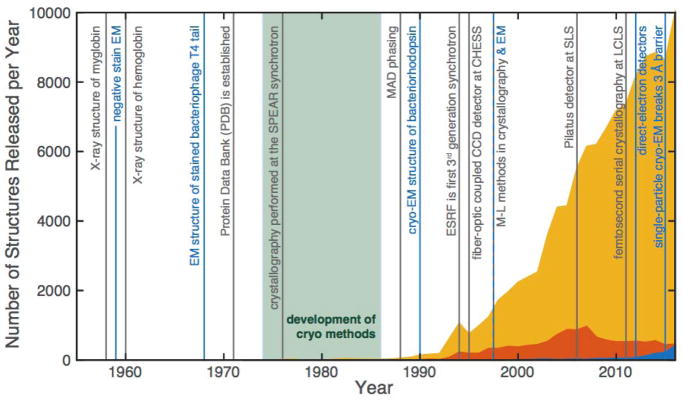

Since its inception, X-ray crystallography has been used to determine over 112,000 structures of proteins in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), making it the most widely used technique for protein structure determination. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy comes in second, claiming responsibility for 10,500 protein structures. Electron microscopy (EM), on the other hand, is responsible for just over 1,200 protein structures. However, in the last five years or so, cryo-EM has experienced a “resolution revolution,” resulting in a flurry of high-resolution structures,1 and at the time of this writing (October, 2017), has surpassed NMR in the number of structures released in the PDB per year (Figure 1). Will cryo-EM surpass X-ray crystallography? To provide context for this question, we first review the intertwined history of X-ray crystallography and EM. In the following sections, we share insights from leaders in both fields and describe four key considerations in envisioning the future of the two techniques: crystallization, resolution and model quality, temperature, and dynamics. Finally, we discuss how the two techniques might leverage their unique capabilities to shape the future of structural biology, both separately and in parallel.

Figure 1.

Historical milestones in macromolecular X-ray crystallography and electron microscopy. The number of structures released yearly in the PDB is shown by technique: X-ray crystallography (yellow), NMR (orange), and EM (blue). Notably, cryo-crystallography and cryo-EM were developed around the same time (green shaded region), but the availability of synchrotron light sources accelerated the growth of X-ray crystallography. For both techniques, detector technology has had enormous impact. The charge-coupled device (CCD) detector, such as the one developed at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS), became a widespread tool in synchrotron-based macromolecular crystallography. Today, photon-counting pixel-array detectors, such as the Pilatus, first commissioned at the Swiss Light Source (SLS), account for more than half of the crystal structures being deposited in the PDB. A pixel-array detector also enabled serial crystallography with femtosecond X-ray pulses at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), the world’s first hard X-ray free electron laser (XFEL). Around the same time, direct-electron detectors became commercially available, giving rise to the cryo-EM revolution. Advances in both crystallography and EM were also made possible by the development of algorithms, such as those based on maximum-likelihood (M-L).

An Intertwined History

The Crystallization of Structural Biology

X-ray crystallography was invented in the early 20th century, before the development of quantum mechanics.2 X-rays had been discovered by Wilhelm Röntgen less than two decades prior. In the wake of this discovery, the wave property of X-rays was still highly controversial. The experiment that would provide an answer was conceived in 1912 in a conversation between Max von Laue and Paul Ewald. At the time, it was already known that the fine lattice structures of crystalline materials were too small to observe, as the wavelength of visible light was too long. Laue hypothesized that if X-rays were indeed waves, then they may have wavelengths short enough to match the interatomic distances of crystals. A few months later, Laue’s colleagues, Walter Friedrich and Paul Knipping, placed various salt crystals in front of an X-ray beam and observed diffraction, irrefutably proving the wave nature of X-rays as well as the angstrom-scale lengths of chemical bonds.3 The experiment was not only a breakthrough in the development of modern physics, but also had immeasurable impact on chemistry. The following year, the son-and-father pair, Sir William Lawrence Bragg and Sir William Henry Bragg, determined the structures of sodium chloride and diamond using X-rays in the first complete instances of the structural technique we now know as X-ray crystallography.

Electron microscopy was developed just shy of two decades after X-ray crystallography, after Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll conceived of the electron-focusing magnetic lens. In 1931, Ruska and Knoll built a prototype of the first electron microscope, and in 1933, they succeeded in developing trans-mission electron microscopy (TEM), thus overcoming the resolution barrier imposed by visible light. By then, Louis de Broglie’s theory of the wave-particle duality of matter had been experimentally established, and it was known that high-energy electrons would have short wavelengths. Controlling magnetic fields, however, is highly challenging, and thus lens technology limited the resolution of the early electron microscopes to only 20–100 Å. Single-particle EM of individual proteins would not be possible for many more decades. Even today, lens aberrations remain the primary factor that limits the resolution of EM to 0.5–1 Å, which is much greater than the 0.02 Å de Broglie wavelength theoretically achievable at 300 kV.

By the 1930s, it was already known that proteins could arrange to form crystals.4 In fact, hemoglobin crystals from roughly 200 different organisms had already been reported in 1909.5 However, it was not known that unlike salt crystals, protein crystals contain water and could not be allowed to dry. Thus, it was not until 1934 that X-ray diffraction from a hydrated protein crystal was observed for the first time through the work of J. Desmond Bernal and Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin.6

Solving structures of macromolecules, however, remained challenging, due to the loss of phase information that occurs in the measurement of scattered X-rays. Although the structure of the DNA double helix had been deduced from fiber diffraction in 1953, de novo structure determination from crystal diffraction was impossible until Max Perutz developed the isomorphous replacement method in 1956.7 Finally, in 1958, Sir John Kendrew and his colleagues solved the first X-ray structure of myoglobin to a resolution of 6 Å.8 Just two years later, the group solved the structure of myoglobin at 2-Å resolution,9 marking the first time that a protein’s structure was determined at the atomic level. In the same year, Perutz solved the structure of hemoglobin at 5.5 Å.10 These pioneering studies marked what has been called the “big bang” of the discipline we now know as structural biology.11

In the following decade, EM presented its own solution to the phase problem. By the 1960s, the electron microscope had produced steady improvements in achievable resolution. In 1959, Sydney Brenner and Robert Horne made biological EM practical by inventing negative staining, a process that is still in use today, in which biological samples are embedded in heavy metal salts to increase contrast and maintain overall shape information under the high-vacuum environment within an electron microscope.12 At this time, single-particle EM was not yet feasible. However, with negative staining, crystals and other samples with high symmetry provided ways to amplify the weak signal. David DeRosier and Aaron Klug were thus able to collect electron micrographs of T4 bacteriophage tail with sufficient contrast to perform Fourier-based analyses computationally.13 Making use of the helical symmetry of the T4 tail and the fact that refocusing the scattered electrons generates a 2D image that retains the original phases, they determined the first 3D structure to a resolution of 35 Å in 1969, paving the way for crystallographic EM.

Not surprisingly, negative staining was not a reliable method for preserving order within the thin (2D) protein crystals required for electron crystallography. The grain size of heavy metal salts and distortions introduced by the staining process limit the resolution of negative stain specimens to ~20 Å.14 Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, alternative methods were developed. In a landmark 1975 study, Richard Henderson and Nigel Unwin solved the structure of bacteriorhodopsin to 7-Å resolution by using EM to image glucose-embedded 2D crystals.15 Though the contrast afforded by glucose embedding was weak, the redundancy in the lattice yielded strong diffraction that allowed the resolution of α-helices, demonstrating the potential of EM to probe the internal structures of proteins for the first time.

The Birth of Cryo-crystallography and Cryo-EM

As both X-ray and electron crystallography gained traction, overcoming the radiation susceptibility of biological macromolecules became increasingly critical. The onset of radiation damage is very clear in diffraction images as the damaged-induced disorder leads to the disappearance of diffraction spots, starting at the highest resolution. By the 1970s, cooling protein crystals had been attempted by a number of groups as a way to mitigate radiation damage.16,17 Simply freezing crystals would not work, however, as the formation of crystalline ice destroys the protein lattice. Instead, it was necessary to induce formation of a glassy phase of ice by rapidly cooling the crystals to below the temperatures at which crystalline ice is favored. This process, known as vitrification, presented unique challenges to each field. In EM, sample thickness had to be controlled prior to cooling in order to produce samples thin enough to minimize multiple scattering events by electrons. In crystallography, larger crystals yield stronger signals, but are harder to cool rapidly. Hence, methods to prevent damage to the crystal lattice during the cooling process were critical. In 1982, Jacques Dubochet and colleagues invented methods to reliably vitrify EM samples by plunging them into liquid ethane or propane, rather than liquid nitrogen.18 This innovation, combined with earlier work by Ken Taylor and Bob Glaeser,17 solved the central technical challenges to making cryo-EM a reliable technique. Soon after, in 1988, Håkon Hope reported the use of oil as a general method to cryo-protect crystals for X-ray crystallography, enabling the collection of complete datasets from single crystals.19 With these innovations, both cryo-crystallography and cryo-EM were born.

At this time, X-ray crystallography was on the brink of a revolution, thanks to a confluence of technological, algorithmic, and biological advances. Perhaps the most important of these was the introduction of synchrotron radiation in the 1970s.20 With cryo-cooling made practical, crystallography could now fully take advantage of the high-intensity and tunable X-rays generated by synchrotrons. The ability to tune the X-ray energy enabled the development of the multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) technique by Wayne Hendrickson and others in the 1980s.21 Combined with advances in molecular biology, anomalous dispersion techniques have made phasing routine in crystallography. In particular, the incorporation of selenomethionine in place of methionine in protein sequences led to the development of Se-MAD phasing.22 The resulting rapid growth of the Protein Data Bank (PDB) also allowed more structures to be solved by molecular replacement methods, developed by Michael Rossmann and others.23 Additionally, the introduction of synchrotron facilities meant that crystallography was now part of a greater X-ray science community. By the 1990s, third-generation synchrotron sources were coming online, increasing the number of macromolecular crystallography beamlines to >100, with a proportional number of supporting staff scientists.24 Around the same time, the charge coupled device (CCD) detector replaced older technologies,25 greatly reducing data collection times, and the introduction of data processing and maximum likelihood-based refinement software packages26–28 made structure determination both accurate and user-friendly. The X-ray crystallography pipeline was now complete: crystals could be grown and cryo-cooled in the laboratory and transported to synchrotron facilities for data collection, and crystal structures could be solved at home or even at the beamline.

The advent of sample vitrification also had an immediate impact on crystallographic EM. In 1990, Henderson and colleagues reported the first EM structure to near-atomic resolution using cryo-cooled crystals of bacteriorhodopsin.29 However, with the success of X-ray crystallography, the next frontier in EM was in obtaining 3D structures from randomly oriented single particles, rather than relying on samples in highly periodic arrays. Prior to the 1980s, the redundancy in highly symmetric samples, such as 2D crystals and viruses, had been leveraged to perform 3D reconstructions, but a generalized single-particle approach was not feasible. Still, development of theoretical advances in single-particle reconstruction continued, and over the course of the 1980s, these methods were realized for large, stable macromolecules. In 1984, Joachim Frank and colleagues reported the first 3D single-particle reconstruction of an asymmetric particle, the 30S subunit of the ribosome.30 To reconstruct a 3D view of a protein molecule from 2D TEM images, the individual particles must be first picked and therefore must be distinguishable from noise. The particles are then typically aligned and classified to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. By determining the relative orientations of these class averages, it is possible to reconstruct a 3D volume.31 The common-line-based angular reconstitution method32 represents one such approach.

Both X-ray and cryo-EM structure determination relies on solving underdetermined problems. In other words, part of the data needed to obtain a complete structure is missing. In X-ray crystallography, the missing data consist of unknown phases. In 1988, Gérard Bricogne presented a Bayesian approach to solving the phase problem,33 which provided the theoretical basis for the eventual application of maximum likelihood methods to X-ray crystallography. Cryo-EM relies on the same statistical framework to recover the missing orientations of the particles seen in 2D projection images. Fred Sigworth first introduced the maximum likelihood approach for the alignment problem in cryo-EM.34 Today, maximum likelihood approaches have become the norm due to advances in computing power.

As EM transitioned from a crystallographic method to a true single-particle method, however, it faced a major technological hurdle in measurement. Achieving high resolution was much easier with electron diffraction than with imaging, largely due to a phenomenon that is still poorly understood: electron-induced movement of the molecules within the ice matrix. It is well known among crystallographers that translating a crystal within a beam does not change the center of the diffraction image. However, this is not true for imaging, where beam-induced motion or any type of drift in sample position leads to blurring. Thus, sample vitrification alone was not enough to overturn the low-resolution paradigm that defined single-particle EM.

When the first direct-electron detectors became commercially available in 2012, however, lower bounds on resolution plummeted. Not only did these detectors provide greater sensitivity, but more critically, their fast framing rate enabled image deblurring of electron-induced motion over the course of imaging.14 This development, coupled with the timely introduction of powerful new single-particle reconstruction algorithms,35 contributed to the gain in resolution, while the introduction of phase plates has provided additional contrast.36 By 2013, the structure of the 4 MDa Saccharomyces cerevisiae 80S ribosome had been solved to 4.5 Å,37 and just a few years later, cryo-EM broke the 3-Å resolution barrier with the 700 kDa Thermoplasma acidophilum 20S,38 marking the start of the cryo-EM revolution.

New Directions

Perhaps most remarkably, recent developments in cryo-EM have shown that the technique is no longer limited to giant macromolecules and assemblies. In 2016, cryo-EM broke its traditional 200-kDa barrier with two <4-Å structures,39 and in a symbolic endeavor in 2017, the structure of hemoglobin (64 kDa) was determined to 3.2-Å resolution,40 putting cryo-EM in a molecular range that has traditionally been squarely within the purview of X-ray crystallography. Until now, the domains of cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography have remained largely distinct. Now, the samples accessible to the two techniques are beginning to overlap.

Could cryo-EM replace crystallography? Many may view the coming-of-age of cryo-EM as signaling the end of X-ray crystallography. For most structural biologists, however, it will not be “either or” but rather, “whatever works”. Furthermore, developers of the techniques will likely view this as an opportunity to innovate in new ways. Although cryo-EM has become more like X-ray crystallography in terms of accessible samples and achievable resolution, its differences have also become more apparent, signaling the start of a new era in structural biology where the unique capabilities of both techniques can be leveraged to produce complementary, rather than competing, views of biological macromolecules. Here, we will consider four areas in which X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM diverge: crystallization, resolution, temperature, and dynamics.

“Consider an analogy: The cell phone camera has not replaced the stand-alone optical camera. Rather, it has replaced cheap cameras. For professional imaging the camera is alive and well, and ever improving with the introduction of new digital methods to process images.”

– Sol Gruner, Professor of Physics at Cornell University and former director of the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS).

Revisiting Crystallization and Defining Frontiers

The main obstacle to routine, high-resolution structure determination in crystallography has historically been the “crystallization bottleneck,” the tedious task of coaxing molecules into their crystalline form. The first major attempts to overcome the crystallization bottleneck were made by structural genomics efforts, such as the Protein Structure Initiative (PSI) in the U.S. and the RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative in Japan, which sought to determine the structures of novel folds by mining the wealth of genome sequencing data that were becoming available by the 2000s. In order to meet their goals of producing many new structures, these efforts created an increased demand for the development of high-throughput crystallization and structure determination pipelines.24 The high level of automation at crystallography beamlines today derives from this effort.

By this period, the X-ray field had entered a race to invent a new generation of light sources, which were entirely distinct from any synchrotron technology that had existed before.41,42 In 2009, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) became the first hard X-ray free electron laser (XFEL) to begin operation. Unlike previous light sources, in which radiation was derived from charged particles retained in a circular storage ring, the XFEL is a linear accelerator that produces extremely bright, coherent X-rays, one pulse at a time. The pulses generated by the LCLS were so bright that they necessitated the development of a new type of crystallography that would overcome the near-instantaneous destruction of the samples. The result was the development of serial crystallography, in which a stream of randomly oriented microcrystals is injected into an X-ray beam.43 Importantly, the microcrystals do not need to be cryo-cooled. A single diffraction image is measured from a single crystal within the femtosecond pulse durations, before the onset of atomic motions caused by radiation damage, and the data from many crystals are merged.

This method, colloquially known as “diffraction before destruction,” has been championed as a way to obtain long-awaited, damage-free structures of key macromolecules, the most prominent being photosystem II (PSII). The oxygen-evolving complex of PSII is especially susceptible to radiation damage, but high-resolution, damage-free structures could revolutionize our understanding of oxygenic photosynthesis.44 Serial crystallography has also challenged the notion that crystallization must be non-physiological. An early example is a 2013 study carried out at the LCLS by Henry Chapman, Christian Betzel, and others, which resulted in a 2.1-Å structure of the natively inhibited Trypanosoma brucei cathepsin B.45 Significantly, the microcrystals that led to this structure were formed spontaneously in vivo and were harvested from insect cells. As a result, the structure revealed post-translational modifications that could only occur under native conditions.

Perhaps more significantly, the advent of the XFEL has led to a reboot in crystallography at storage rings. In particular, the development of serial crystallography has led the synchrotron community to revisit old ideas that were forgotten in favor of cryo-crystallography. Whereas the first 50 years of macromolecular crystallography culminated in the development of cryo-crystallography, the field is now making a return to room-temperature measurements as a key step towards obtaining dynamic information. The revival of such room-temperature studies at storage ring synchrotrons has yielded valuable information about conformational flexibility.

Cryo-EM has been able to overcome the crystallization bottleneck altogether. However, the shift to-ward room-temperature diffraction means that cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography can innovate in different directions. Although the XFEL aims to achieve single-particle scattering, it will likely be difficult to compete with single-particle EM for some time. Thus, an area in which single-particle cryo-EM can make unique headway is in revealing the structures of increasingly large and heterogeneous assemblies that cannot be crystallized. Likewise, it is unlikely that high-resolution EM will be possible as a function of temperature or at short timescales. By contrast, X-ray crystallography provides precise structural information and is better suited for probing dynamics. We elaborate on these differences in the following sections.

“The frontiers in structural biology are very clearly larger systems and systems in situ.”

– Joachim Frank, Professor of Biological Sciences at Columbia University and recipient of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

“The frontiers in structural biology include mapping the entire conformational landscape, and getting away from the static view of the molecule.”

– Henry Chapman, Professor of Physics at the University of Hamburg and leader of the Coherent X-ray Imaging division at Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY).

“EM will not completely replace crystallography, but it will definitely give it a run for its money, especially for things that are hard to crystallize, such as large complexes and membrane proteins, and provide information about essential conformational changes and interactions that would simply not be accessible through crystallography”

– Francisco Asturias, Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics at University of Colorado.

On B-factors, Resolution, and Maps

“The bad news about constraint of motion is that you may constrain the material to a conformation that’s not representative of what it assumes when it’s an independent molecule… The good news is you constrain the motion, which means that the B-factors are reduced, which means you see more.”

– Peter Moore, Professor of Chemistry at Yale University.

Today, X-ray crystallography still represents the technique of choice for high-resolution structural biology. In 2017, X-ray crystallography produced over 10,000 protein structures in the PDB, 92% of which had resolutions better than 3 Å. By comparison, only 12 single-particle EM maps with resolutions better than 3 Å were deposited in the EM Data Bank the same year for structures <1 MDa in size. As high-resolution cryo-EM continues to grow, however, it is important to consider how each field reports the resolution and what the maps obtained from each technique mean.

A useful analogy to understand resolution in crystallography is the way resolution is defined in photography or optical microscopy, in which scattered light from an object is refocused by a lens to form an image. The resolution is defined as the minimum distance at which two points in the object can be distinguished in the image. This resolution is set by the solid angle of scattered light that the lens can collect. It follows that the greater the size of the lens, the greater the angle it can collect, and the greater the resolution of the image. In X-ray crystallography, the resolution can be defined equivalently by the length scale associated with the largest scattering angles at which diffraction peaks or so-called reflections can be observed. Practically speaking, the resolution cutoff is chosen based on how well these outer reflections can be integrated and distinguished from noise.

The resolution of crystallography is ultimately limited by the degree of order in the crystal lattice. Disorder causes an apparent disappearance of the diffraction pattern, starting from the high-resolution reflections. This decay is modeled by the thermal B-factor, a measure of how much atoms deviate from their average positions. However, an underappreciated but significant advantage of crystallization is that the average atomic coordinates have high precision. While dependent on the data-to-parameter ratio, systematic estimations have shown that the precision of crystallographic models is generally sub-angstrom.46–48 A notable example is a study of citrine, a yellow variant of the green fluorescent protein, for which a series of structures were solved to ~2-Å resolution using high-pressure crystallography.48 It was shown that application of hydrostatic pressure induces a sub-angstrom translation of the stacked aromatic rings in the chromophore, leading to a 20-nm shift in the fluorescence spectrum. These changes were detectable because each of these pressure-dependent structures had a precision in the range of 0.1 to 0.2 Å.

In cryo-EM, defining resolution is a more complex matter. The reported resolution in cryo-EM is not a function of the lens of the electron microscope. Rather, it is a measure of self-consistency in the data and the reconstruction process used to generate the 3D map.49 Typically, this value is determined by computing the Fourier shell correlations (FSC) of two independently computed maps, each based on half of the available images.50 The resolution limit corresponds to the Fourier shell beyond which the FSC drops below a threshold value. Commonly used FSC thresholds range from 0.143 or 0.5, but how the threshold is determined remains debated.51 High-resolution structural features in EM images are more susceptible to loss of contrast due to both experimental and computational errors. This contrast loss can be modeled as a Gaussian decay with a B-factor,52 in a manner that is conceptually similar to that in crystallography, and the inverse can be applied to generate “sharpened” EM maps.

Given the differences in the way resolution are determined, it can be questioned whether maps and structural models from cryo-EM are comparable to those in crystallography. In a recent study, it was argued that they are not equivalent.53 A qualitative comparison with crystallographic maps at the same resolution showed that sharpened EM maps appeared to have irregular features and additional noise. Further, and more concerning, reported B-factors were often non-physical. Unlike in crystallography where the B-factor is well defined and can be refined against the experimental data, the contrast loss in cryo-EM contains contributions that cannot be easily modeled, such as errors in particle alignment. Thus, if only unconstrained real-space refinement is undertaken, this may lead to a situation where B-factors are wildly different between covalently bonded atoms, which makes little physical sense.

A better question is perhaps whether EM maps should be treated the same way as crystallography maps. The 3D maps that cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography yield are fundamentally different. Elastic scattering of X-rays is inversely dependent on the mass of the charged particles, and hence, X-rays primarily interact with the electrons around an atom rather than the nuclei. As such, X-ray crystallography gives rise to electron densities. By contrast, electron scattering is sensitive to both the electrons and atomic nuclei, yielding a map of electric potential. At resolutions better than 1 Å, X-ray and EM maps are expected to exhibit marked changes, according to a recent study by Jimin Wang and Peter Moore.54 In this study, they examined electric potential maps obtained via cryo-EM to show that the Asp-411 residue in β-galactosidase is protonated, unlike most Asp residues, which are deprotonated at neutral pH.

Overall, three conclusions can be drawn. First, there is an inverse correlation between resolution and B-factor, regardless of how they are defined. Crystallography can be expected to generate high-resolution structures as motions are generally more constrained in the lattice. In cryo-EM, molecules will not be constrained by a lattice and hence, will be able to sample more physiological conformations (though it is important to note that reconstructions produced via cryo-EM typically reflect the most populated conformation, which may not be the biologically interesting one). However, the resolution will still be limited by the spread within an alignment of particles and the loss of contrast. Secondly, at high resolution, both X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM have the potential to yield detailed insight into biochemical processes, such as the catalytic mechanisms of enzymes. Whereas crystallography can yield information on atomic positions with sub-angstrom precision, cryo-EM can reveal the protonation state of catalytically important residues. Finally, refinement of structural models within EM maps should not be performed at atomic resolution with assumptions from X-ray scattering.

On Temperature

“Freezing is problematic. The general assumption is that if I take a very small crystal and freeze it, I essentially freeze-frame it, in other words, I’ve simply stopped all the dynamic processes going on in the crystal all at once, and it’s like a still taken out of a movie. The problem is you can’t freeze them that fast.”

– Peter Moore

Considerations of resolution aside, it bears repeating that a major appeal of cryo-EM is its independence from the crystallization process. Apart from the obvious advantage of simpler sample preparation, this affords another major benefit: the ability to observe molecules in their “near-native” states. Not only are vitrified samples fully hydrated, but the cryo-cooling process has been shown to capture multiple conformational states, leading many to hypothesize that cryo-EM provides a fairly accurate picture of how molecules might behave in their native states. A more illustrative, if less immediate example is the prospect of using cryo-electron tomography to eventually study the structure of macromolecules and other cellular components, in situ.

A major assumption that has not yet been validated, however, is that cryo-cooled structures are representative of the physiological state. At room temperature, all of the dynamic processes in a molecule have the same thermodynamic temperature. If it were possible to stop all of these processes at once, then the resulting frozen snapshot will be perfectly representative of the time-average of the room-temperature distribution of states. In reality, it is not possible to freeze instantaneously. Instead, as we cool the sample, some dynamic processes may “freeze out” before others. By the time the sample has reached cryogenic temperatures, some room-temperature processes may be well represented, while others may be trapped in states with an ill defined temperature.55

Compared to a decently sized crystal for X-ray diffraction, which has dimensions of ~100 μm on each edge, cryo-EM samples must be extremely thin, typically less than the longest dimension of a bacterial cell (1000 Å or 1 μm). Thus, a major advantage of cryo-EM is that samples can be vitrified much more quickly and are likely to better approximate the room-temperature state.

Importantly, however, X-ray crystallography can be performed at ambient temperatures, and the question of freezing out dynamics in cryo-crystallography is actively being investigated through systematic comparisons of diffraction data that were collected at room and cryogenic temperatures. One approach to determine if room-temperature dynamics are faithfully represented in a cryo-cooled crystal is to refine ensemble or multiconformer models again diffraction data. Applications of the latter model, in which each residue may adopt several different conformations, have suggested that crystal cryo-cooling can introduce significant changes to the protein structural ensemble.56 A second approach, which has not been done, would take advantage of a phenomenon known as diffuse scattering.57 Diffuse scattering is the weak, continuous X-ray scattering that results from imperfections in a crystal. The lack of perfect constructive and destructive interference arising from these imperfections results in some scattering around and beneath Bragg peaks. It follows that the resultant diffuse scattering patterns contain information on the origin of the imperfections, including those arising from protein dynamics. A careful comparison of the diffuse scattering at multiple temperatures would yield a definitive answer to whether cryo-cooling is altering the conformational landscape of proteins. The challenge, however, is that cryo-cooling may create lattice disorder, which will also contribute to the diffuse scattering. Regardless, it is clear that we are moving in a direction where we can begin to seriously investigate the effects of temperature on the conformational landscapes of macromolecules.

Motion and Conformational Heterogeneity

A central focus of structural biology going forward is moving beyond the static pictures of macro-molecules and relating molecular motion to biological function. Untangling this relationship is no simple endeavor and requires multiple approaches.

X-rays are uniquely suited to capture time-resolved molecular “movies” on fast time scales.58 Two crystallographic approaches have been taken toward this aim. The first approach, known as time-resolved Laue crystallography, circumvents the need to rotate a crystal to collect an entire dataset by using a polychromatic X-ray beam to satisfy many Bragg conditions at once from a single orientation of the crystal. By using short X-ray pulses available at 3rd generation synchrotrons, time-resolved diffraction can be measured in a pump-probe experiment. Although laser-pump, X-ray-probe experiments of light-activated proteins are the best-known examples of this method,59,60 more exotic pumps have also been employed. In 2011, temperature jumps between 100 and 180 K were used to probe reaction intermediates in the photo-receptor protein, bacteriophytochrome,61 and in 2016, electric field pulses were used to drive concerted motions within a crystal on the sub-μs timescale.62

The emergence of XFELs has enabled a second approach based on serial crystallography, where pump-probe diffraction measurements are performed on many randomly oriented microcrystals. The ultra-short X-ray pulses that XFELs generate have been used to enable extremely fast pump-probe experiments for several years. For example, the mechanism of O=O bond formation in the oxygenic photosynthesis is an area of active interest. Recently, two pump-probe studies of PS II were published in quick succession, one from the LCLS in 2016 and the other from the SPring-8 Angstrom Compact Free Electron Laser (SACLA) in 2017.63,64 Slower kinetics can be probed by mix-and-inject methods.65 Here, the reaction is initiated by mixing a small molecule that diffuses into solvent channels of the crystals. The use of microcrystals is an advantage for both pump-probe and mix-and-inject methods, as reactions can be initiated more uniformly and rapidly within each crystal.

Dynamic information can also be obtained by X-ray scattering methods. For example, diffuse scattering from crystals, which was described in the previous section, contains information on the disorder that gives rise to the B-factor. A potentially powerful application of diffuse scattering is in giving physical meaning to the B-factors obtained by crystallography.57 Of the various types of disorder that we may see in the diffuse scattering pattern, the most exciting is the correlated motions that underlie protein allostery.66 Solution-based small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS/WAXS) provides yet another method for observing protein dynamics.57 While not a high-resolution technique, it is unique in that it probes macromolecules in solution, meaning that experimental conditions can be easily varied. Thus, SAXS/WAXS can provide a means to explore the full extent of the conformational landscape as a function of any number of solution conditions. More significantly, solution scattering provides a straightforward way to perform time-resolved studies under physiologically relevant conditions.67,68

Time-resolved cryo-EM, by contrast, operates on a much coarser time scale and is limited by the ~10 ms dead time required to spray the sample and cryo-cool the EM grid.69 However, it is uniquely suited to reveal discrete conformations within an ensemble. Notable examples include the metazoan cytosolic fatty acid synthase, for which a near continuum of conformations was observed by single-particle, negative-stain EM in 200970 and the distinct conformations of a full-length polyketide synthase module from the pikromycin biosynthesis pathway resolved by single-particle cryo-EM in 2014.71,72

A better strategy for the interpretation of conformational variability takes into consideration continuous conformational landscapes, as opposed to discrete conformations, and their corresponding probabilities. Joachim Frank and Abbas Ourmazd recently demonstrated the capability of a computational method known as manifold embedding to accomplish this goal, representing a departure from the maximum likelihood methods that are typically used to resolve conformational heterogeneity.73 Unlike maximum likelihood, manifold embedding extracts continuous conformational changes, and it does so without the use of a model (though smoothness in high-dimensional pixel space is assumed). Instead of sorting conformations into discrete groups, a process which throws out valuable information about the relationships between various conformations, the manifold-embedding approach aims to capture the entire conformational ensemble. Using this approach, it has proven possible to determine the energy landscape of the ribosome and connect this to its function. Most recently, Frank and colleagues developed a clever approach to probing the binding mechanisms of molecules by comparing the conformational landscapes from molecules bound with substrate to molecules in their unbound form.74

“The ability to even reconstruct energy landscapes from experimental data is really sensational, at least to me.”

– Joachim Frank

Toward an Integrated Approach

“The biggest obstacle is not what can be done, but rather limited imagination as to what is possible.”

– Sol Gruner.

Over its long history, X-ray crystallography and EM have benefited from the cross-pollination of ideas. From the standpoint of both structural and functional insights, it is clear that X-rays and EM have complementary, rather than competing, capabilities. Moreover, constraint of motion, resolution, temperature, and dynamics are all linked and should not be considered in isolation. Whereas cryo-EM obviates the need for crystallization, constraining molecules to a crystal lattice yields higher resolution and precision. Conversely, molecules that are not constrained to a lattice can access larger conformational degrees of freedom, which may be physiologically important. Likewise, vitrification is a far more rapid process for EM specimen than for crystals used in X-ray crystallography, and hence, the conformations trapped in cryo-EM are more likely to be representative of the room-temperature state. However, unlike EM, X-ray crystallography can yield high-resolution information at non-cryogenic temperatures and is thus better suited to probing dynamics as a function of external perturbations. Thus, there are tradeoffs between crystallization versus gain in resolution and cryo-cooling versus gain in dynamic information.

The future of structural biology will therefore be best served by integrating both X-ray and EM data. The most common approach thus far to combining their capabilities has been to dock X-ray structures in EM maps to generate so-called pseudo-atomic resolution models. More advanced forms of docking such as “flexible fitting” have also been introduced,75 in which a molecule’s conformational flexibility is simulated by molecular dynamics in order to facilitate fitting of X-ray structures. Another example of integrating X-ray and EM data involves determination of the EM B-factor. Because contrast loss is dependent on factors that cannot be predicted, a reasonable approach to derive the EM B-factor is to compare the amplitude decay in a power spectrum of the electron micrograph with that of small-angle X-ray scattering.76 In the reverse direction, it has been shown that it is possible to use cryo-EM maps to phase X-ray diffraction data.77

To successfully integrate data from different structural techniques in the future, it will become increasingly critical to understand the theoretical underpinnings of how they relate to one another. X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM are often presented as comparable high-resolution structural techniques with the only notable differences between them pertaining to sample preparation and accessibility. However, as we have discussed in this perspective, the data that the two techniques yield are fundamentally different. For example, it will be interesting to see how cryo-EM will utilize the information contained in electric potential maps. Furthermore, basic questions remain for both X-ray and cryo-EM methods. For example, what is the physical basis for electron-induced motion of particles? Are we certain that diffraction can be collected before destruction at an XFEL? These are interesting and important questions as catalytic mechanisms and oxidation states of co-factors are likely to be sensitive to charging and ionization effects. As these techniques continue to become more advanced, we look forward to gaining deeper insight into such questions.

To conclude, cryo-EM will not replace crystallography, but the competition between these two techniques will drive innovation and specialization of these techniques to areas in which they excel. The fruit of this competition will push the frontiers of structural biology forward, possibly for decades to come, perhaps finally allowing us to cast a lens on macromolecular assemblies in vivo, understand the motions of proteins, and gain a high precision view into catalysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Drs. Francisco Asturias, Henry Chapman, Sol Gruner, Joachim Frank, and Peter Moore for offering insightful comments in the preparation of the manuscript. The authors are also grateful to Drs. Buz Barstow and James Chen for useful discussions on crystallography and EM and to Will Thomas for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by National Health Institutes (NIH) grants GM100008 GM124847 and start-up funds from Princeton University to NA.

References

- 1.Nogales E. The development of cryo-EM into a mainstream structural biology technique. Nature Methods. 2016;13:24–27. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaskolski M, Dauter Z, Wlodawer A. A brief history of macromolecular crystallography, illustrated by a family tree and its Nobel fruits. FEBS J. 2014;281:3985–4009. doi: 10.1111/febs.12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Laue M. Kritische Bemerkungen zu den Deutungen der Photogramme von Friederich und Knipping. 1913;14:421–423. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPherson A. A brief history of protein crystal growth. Journal of Crystal Growth. 1991;110:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichert ET, Brown AP. The Differentiation and Specificity of Corresponding Proteins and Other Vital Substances in Relation to Biological Classification and Organic Evolution: The Crystallography of Hemoglobins. Carnegie Institution; Washington, DC: 1909. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernal JD, Crowfoot D. X-ray Photographs of Crystalline Pepsin. Nature. 1934;133:794–795. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perutz MF. Isomorphous replacement and phase determination in non-centrosymmetric space groups. Acta Cryst. 1956;Q9:867–873. doi: 10.1107/S0365110X56002485. 9 , 1–7 1107/S0365110X56002485] 9, 1–7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendrew JC, Bodo G, Dintzis HM, Parrish RG, Wyckoff H, Phillips DC. A three-dimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by x-ray analysis. Nature. 1958;181:662–666. doi: 10.1038/181662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kendrew J, Dickerson R, Strandberg B, Hart R, et al. Structure of Myoglobin: A Three-Dimensional Fourier Synthesis at 2 Å. Resolution. Nature. 1960 doi: 10.1038/185422a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perutz M, Rossmann M, Cullis A, Muirhead H, Will G, North AC. Structure of haemoglobin: a three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 5.5-A. resolution, obtained by X-ray analysis. Nature. 1960;185:416–422. doi: 10.1038/185416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossmann MG. John C. Kendrew and His Times. J Mol Biol. 2017;429:2601–2602. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brenner S, Horne RW. A negative staining method for high resolution electron microscopy of viruses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1959;34:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Rosier DJ, Klug A. Reconstruction of three dimensional structures from electron micrographs. Nature. 1968;217:130–134. doi: 10.1038/217130a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmlund D, Elmlund H. Cryogenic Electron Microscopy and Single-Particle Analysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:499–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson R, Unwin PN. Three-dimensional model of purple membrane obtained by electron microscopy. Nature. 1975;257:28–32. doi: 10.1038/257028a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petsko GA. Protein crystallography at sub-zero temperatures: cryo-protective mother liquors for protein crystals. J Mol Biol. 1975;96:381–392. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor KA, Glaeser RM. Retrospective on the early development of cryoelectron microscopy of macromolecules and a prospective on opportunities for the future. J Struct Biol. 2008;163:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubochet J, Lepault J, freeman R, Berriman JA, Homo JC. Electron microscopy of frozen water and aqueous solutions. J Microsc. 1982;128:219–237. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hope H. Cryocrystallography of biological macromolecules: a generally applicable method. Acta Cryst. 1988;B44:22–26. doi: 10.1107/S0108768187008632. 44, 1–5 1107/S0108768187008632] 44, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dauter Z, Jaskolski M, Wlodawer A. Impact of synchrotron radiation on macromolecular crystallography: a personal view. J Synchrotron Rad (2010) 2010;17:433–444. doi: 10.1107/S0909049510011611. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrickson WA, Smith JL, Sheriff S. Direct phase determination based on anomalous scattering. Meth Enzymol. 1985;115:41–55. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(85)15006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendrickson WA, Horton JR, LeMaster DM. Selenomethionyl proteins produced for analysis by multiwavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD): a vehicle for direct determination of three-dimensional structure. EMBO J. 1990;9:1665–1672. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossmann MG. The molecular replacement method. Acta Crystallogr, A, Found Crystallogr. 1990;46(Pt 2):73–82. doi: 10.1107/s0108767389009815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joachimiak A. High-throughput crystallography for structural genomics☆. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:573–584. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiel DJ, Ealick SE, Tate MW, Gruner SM, Eikenberry EF. Macromolecular crystallographic results obtained using a 2048 × 2048 CCD detector at CHESS. Rev Sci Instrum. 1996;67:3361. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ, IUCr Refinement of Macromolecular Structures by the Maximum-Likelihood Method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collaborative Computational Project N. 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. 50, 1–4, 1107/S0907444994003112], 50, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson R, Baldwin JM, Ceska TA, Zemlin F, Beckmann E, Downing KH. Model for the structure of bacteriorhodopsin based on high-resolution electron cryo-microscopy. J Mol Biol. 1990;213:899–929. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verschoor A, Frank J, Radermacher M, Wagenknecht T, Boublik M. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the 30 S ribosomal subunit from randomly oriented particles. 1984;178:677–698. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penczek PA, Grassucci RA, Frank J. The ribosome at improved resolution: new techniques for merging and orientation refinement in 3D cryo-electron microscopy of biological particles. Ultramicroscopy. 1994;53:251–270. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radermacher M, Wagenknecht T, Verschoor A, Frank J. Three-dimensional re-construction from a single-exposure, random conical tilt series applied to the 50S ribosomal subunit of Escherichia coli. J Microsc. 1987;146:113–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1987.tb01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bricogne G. A Bayesian statistical theory of the phase problem. I. A multichannel maximum-entropy formalism for constructing generalized joint probability distributions of structure factors. Acta Cryst. 1988;A54:517–545. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sigworth FJ. A maximum-likelihood approach to single-particle image refinement. J Struct Biol. 1998;122:328–339. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheres SHW. RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagayama K. Another 60 years in electron microscopy: development of phase-plate electron microscopy and biological applications. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo) 2011;60(Suppl 1):S43–62. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/dfr037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bai XC, Fernandez IS, McMullan G, Scheres SH. Ribosome structures to near-atomic resolution from thirty thousand cryo-EM particles. Elife. 2013;2:19748–12. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell MG, Veesler D, Cheng A, Potter CS, Carragher B. 2.8 Å resolution reconstruction of the Thermoplasma acidophilum 20S proteasome using cryo-electron microscopy. Elife. 2015;4:e01963. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merk A, Bartesaghi A, Banerjee S, Falconieri V, Rao P, Davis MI, Pragani R, Boxer MB, Earl LA, Milne JLS, Subramaniam S. Breaking Cryo-EM Resolution Barriers to Facilitate Drug Discovery. Cell. 2016;165:1698–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khoshouei M, Radjainia M, Baumeister W, Danev R. Cryo-EM structure of haemoglobin at 3.2 Å determined with the Volta phase plate. Nature Communications. 2017;8:16099. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pellegrini C. The history of X-ray free-electron lasers. EPJ H. 2012;37:659–708. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gruner SM, Bilderback D, Bazarov I, Finkelstein K, Krafft G, Merminga L, Padamsee H, Shen Q, Sinclair C, Tigner M. Energy recovery linacs as synchrotron radiation sources (invited) Rev Sci Instrum. 2002;73:1402–1406. doi: 10.1107/s090904950301392x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chapman HN, Fromme P, Barty A, White TA, Kirian RA, Aquila A, Hunter MS, Schulz J, DePonte DP, Weierstall U, Doak RB, Maia FRNC, Martin AV, Schlichting I, Lomb L, Coppola N, Shoeman RL, Epp SW, Hartmann R, Rolles D, Rudenko A, Foucar L, Kimmel N, Weidenspointner G, Holl P, Liang M, Barthelmess M, Caleman C, Boutet S, Bogan MJ, Krzywinski J, Bostedt C, Bajt S, Gumprecht L, Rudek B, Erk B, Schmidt C, Hömke A, Reich C, Pietschner D, Strüder L, Hauser G, Gorke H, Ullrich J, Herrmann S, Schaller G, Schopper F, Soltau H, Kühnel KU, Messerschmidt M, Bozek JD, Hau-Riege SP, Frank M, Hampton CY, Sierra RG, Starodub D, Williams GJ, Hajdu J, Timneanu N, Seibert MM, Andreasson J, Rocker A, Jönsson O, Svenda M, Stern S, Nass K, Andritschke R, Schröter CD, Krasniqi F, Bott M, Schmidt KE, Wang X, Grotjohann I, Holton JM, Barends TRM, Neutze R, Marchesini S, Fromme R, Schorb S, Rupp D, Adolph M, Gorkhover T, Andersson I, Hirsemann H, Potdevin G, Graafsma H, Nilsson B, Spence JCH. Femtosecond X-ray protein nanocrystallography. Nature. 2011;470:73–77. doi: 10.1038/nature09750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suga M, Akita F, Hirata K, Ueno G, Murakami H, Nakajima Y, Shimizu T, Yamashita K, Yamamoto M, Ago H, Shen JR. Native structure of photosystem II at 1.95 Å resolution viewed by femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature. 2015;517:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature13991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Redecke L, Nass K, DePonte DP, White TA, Rehders D, Barty A, Stellato F, Liang M, Barends TRM, Boutet S, Williams GJ, Messerschmidt M, Seibert MM, Aquila A, Arnlund D, Bajt S, Barth T, Bogan MJ, Caleman C, Chao T-C, Doak RB, Fleckenstein H, Frank M, Fromme R, Galli L, Grotjohann I, Hunter MS, Johansson LC, Kassemeyer S, Katona G, Kirian RA, Koopmann R, Kupitz C, Lomb L, Martin AV, Mogk S, Neutze R, Shoeman RL, Steinbrener J, Timneanu N, Wang D, Weierstall U, Zatsepin NA, Spence JCH, Fromme P, Schlichting I, Duszenko M, Betzel C, Chapman HN. Natively inhibited Trypanosoma brucei cathepsin B structure determined by using an X-ray laser. 2013;339:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.1229663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tickle IJ, Laskowski RA, Moss DS. Error Estimates of Protein Structure Coordinates and Deviations from Standard Geometry by Full-Matrix Refinement of [gamma]B- and [beta]B2-Crystallin. Acta Cryst. 1998;D54:243–252. doi: 10.1107/S090744499701041X. 54, 1–10 1107/S090744499701041X], 54, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cruickshank DW. Remarks about protein structure precision. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:583–601. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998012645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barstow B, Ando N, Kim CU, Gruner SM. Alteration of citrine structure by hydrostatic pressure explains the accompanying spectral shift. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13362–13366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802252105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liao HY, Frank J. Definition and estimation of resolution in single-particle reconstructions. Structure. 2010;18:768–775. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Penczek PA. Biothermodynamics, Part A. 1. Elsevier Inc; 2010. Chapter 3 - Resolution Measures in Molecular Electron Microscopy; pp. 73–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Heel M, Schatz M. Fourier shell correlation threshold criteria. J Struct Biol. 2005;151:250–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glaeser RM, Downing KH. Assessment of resolution in biological electron crystallography. Ultramicroscopy. 1992;47:256–265. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(92)90201-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wlodawer A, Li M, Dauter Z. High-Resolution Cryo-EM Maps and Models: A Crystallographer’s Perspective. Structure. 2017;25:1589–1597. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J, Moore PB. On the interpretation of electron microscopic maps of biological macromolecules. Protein Science. 2016;26:122–129. doi: 10.1002/pro.3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halle B. Biomolecular cryocrystallography: structural changes during flash-cooling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4793–4798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308315101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fraser JS, van den Bedem H, Samelson AJ, Lang PT, Holton JM, Echols N, Alber T. Accessing protein conformational ensembles using room-temperature X-ray crystallography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16247–16252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111325108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meisburger SP, Thomas WC, Watkins MB, Ando N. X-ray Scattering Studies of Protein Structural Dynamics. Chem Rev. 2017;117:7615–7672. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmidt M. Protein Crystallography. Springer New York; New York, NY: 2017. Time-Resolved Macromolecular Crystallography at Modern X-Ray Sources; pp. 273–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schotte F, Lim M, Jackson TA, Smirnov AV, Soman J, Olson JS, Phillips GN, Wulff M, Anfinrud PA. Watching a protein as it functions with 150-ps time-resolved x-ray crystallography. Science. 2003;300:1944–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.1078797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tenboer J, Basu S, Zatsepin N, Pande K, Milathianaki D, Frank M, Hunter M, Boutet S, Williams GJ, Koglin JE, Oberthuer D, Heymann M, Kupitz C, Conrad C, Coe J, Roy-Chowdhury S, Weierstall U, James D, Wang D, Grant T, Barty A, Yefanov O, Scales J, Gati C, Seuring C, Srajer V, Henning R, Schwander P, Fromme R, Ourmazd A, Moffat K, Van Thor JJ, Spence JCH, Fromme P, Chapman HN, Schmidt M. Time-resolved serial crystallography captures high-resolution intermediates of photoactive yellow protein. 2014;346:1242–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.1259357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang X, Ren Z, Kuk J, Moffat K. Temperature-scan cryocrystallography reveals reaction intermediates in bacteriophytochrome. Nature. 2011;479:428–432. doi: 10.1038/nature10506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hekstra DR, White KI, Socolich MA, Henning RW, Srajer V, Ranganathan R. Electric-field-stimulated protein mechanics. Nature. 2016;540:400–405. doi: 10.1038/nature20571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young ID, Ibrahim M, Chatterjee R, Gul S, Fuller FD, Koroidov S, Brewster AS, Tran R, Alonso-Mori R, Kroll T, Michels-Clark T, Laksmono H, Sierra RG, Stan CA, Hussein R, Zhang M, Douthit L, Kubin M, de Lichtenberg C, Pham LV, Nilsson H, Cheah MH, Shevela D, Saracini C, Bean MA, Seuffert I, Sokaras D, Weng TC, Pastor E, Weninger C, Fransson T, Lassalle L, Bräuer P, Aller P, Docker PT, Andi B, Orville AM, Glownia JM, Nelson S, Sikorski M, Zhu D, Hunter MS, Lane TJ, Aquila A, Koglin JE, Robinson J, Liang M, Boutet S, Lyubimov AY, Uervirojnangkoorn M, Moriarty NW, Liebschner D, Afonine PV, Waterman DG, Evans G, Wernet P, Dobbek H, Weis WI, Brunger AT, Zwart PH, Adams PD, Zouni A, Messinger J, Bergmann U, Sauter NK, Kern J, Yachandra VK, Yano J. Structure of photosystem II and substrate binding at room temperature. Nature. 2016;540:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature20161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suga M, Akita F, Sugahara M, Kubo M, Nakajima Y, Nakane T, Yamashita K, Umena Y, Nakabayashi M, Yamane T, Nakano T, Suzuki M, Masuda T, Inoue S, Kimura T, Nomura T, Yonekura S, Yu LJ, Sakamoto T, Motomura T, Chen JH, Kato Y, Noguchi T, Tono K, Joti Y, Kameshima T, Hatsui T, Nango E, Tanaka R, Naitow H, Matsuura Y, Yamashita A, Yamamoto M, Nureki O, Yabashi M, Ishikawa T, Iwata S, Shen JR. Light-induced structural changes and the site of O=O bond formation in PSII caught by XFEL. Nature. 2017;543:131–135. doi: 10.1038/nature21400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stagno JR, Liu Y, Bhandari YR, Conrad CE, Panja S, Swain M, Fan L, Nelson G, Li C, Wendel DR, White TA, Coe JD, Wiedorn MO, Knoska J, Oberthuer D, Tuckey RA, Yu P, Dyba M, Tarasov SG, Weierstall U, Grant TD, Schwieters CD, Zhang J, Ferré-D’amaré AR, Fromme P, Draper DE, Liang M, Hunter MS, Boutet S, Tan K, Zuo X, Ji X, Barty A, Zatsepin NA, Chapman HN, Spence JCH, Woodson SA, Wang YX. Structures of riboswitch RNA reaction states by mix-and-inject XFEL serial crystallography. Nature. 2017;541:242–246. doi: 10.1038/nature20599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meisburger SP, Ando N. Correlated Motions from Crystallography beyond Diffraction. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50:580–583. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cho HS, Dashdorj N, Schotte F, Graber T, Henning R, Anfinrud P. Protein structural dynamics in solution unveiled via 100-ps time-resolved x-ray scattering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7281–7286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002951107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takala H, Björling A, Berntsson O, Lehtivuori H, Niebling S, Hoernke M, Kosheleva I, Henning R, Menzel A, Ihalainen JA, Westenhoff S. Signal amplification and transduction in phytochrome photosensors. Nature. 2015;509:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frank J. Time-resolved cryo-electron microscopy: Recent progress. J Struct Biol. 2017:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brignole EJ, Smith S, Asturias FJ. Conformational flexibility of metazoan fatty acid synthase enables catalysis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:190–197. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dutta S, Whicher JR, Hansen DA, Hale WA, Chemler JA, Congdon GR, Narayan ARH, Håkansson K, Sherman DH, Smith JL, Skiniotis G. Structure of a modular polyketide synthase. Nature. 2014;510:512–517. doi: 10.1038/nature13423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whicher JR, Dutta S, Hansen DA, Hale WA, Chemler JA, Dosey AM, Narayan ARH, Håkansson K, Sherman DH, Smith JL, Skiniotis G. Structural rearrangements of a polyketide synthase module during its catalytic cycle. Nature. 2014;510:560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frank J, Ourmazd A. Continuous changes in structure mapped by manifold embedding of single-particle data in cryo-EM. Methods. 2016;100:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dashti A, Ben Hail D, Mashayekhi G, Schwander P, Georges des A, Frank J, Ourmazd A. Conformational Dynamics and Energy Landscapes of Ligand Binding in RyR1. 2017:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Orzechowski M, Tama F. Flexible Fitting of High-Resolution X-Ray Structures into Cryoelectron Microscopy Maps Using Biased Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biophys J. 2008;95:5692–5705. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thuman-Commike PA, Tsuruta H, Greene B, Prevelige PE, King J, Chiu W. Solution X-Ray Scattering-Based Estimation of Electron Cryomicroscopy Imaging Parameters for Reconstruction of Virus Particles. Biophys J. 1999;76:2249–2261. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77381-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jackson RN, McCoy AJ, Terwilliger TC, Read RJ, Wiedenheft B. X-ray structure determination using low-resolution electron microscopy maps for molecular replacement. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:1275–1284. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]