Abstract

Human fecal contamination of water is a public health risk. However, inadequate testing solutions frustrate timely, actionable monitoring. Bacterial culture-based methods are simple but typically cannot distinguish fecal host source. PCR assays can identify host sources but require expertise and infrastructure. To bridge this gap we have developed a field-ready nucleic acid diagnostic platform and rapid sample preparation methods that enable on-site identification of human fecal contamination within 80 min of sampling. Our platform relies on loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of human-associated Bacteroides HF183 genetic markers from crude samples. Oligonucleotide strand exchange (OSD) probes reduce false positives by sequence specifically transducing LAMP amplicons into visible fluorescence that can be photographed by unmodified smartphones. Our assay can detect as few as 17 copies/ml of human-associated HF183 targets in sewage-contaminated water without cross-reaction with canine or feline feces. It performs robustly with a variety of environmental water sources and with raw sewage. We have also developed lyophilized assays and inexpensive 3D-printed devices to minimize cost and facilitate field application.

Keywords: Fecal indicator bacteria, fecal source identification, isothermal nucleic acid amplification, portable molecular diagnostics, DNA strand displacement probes

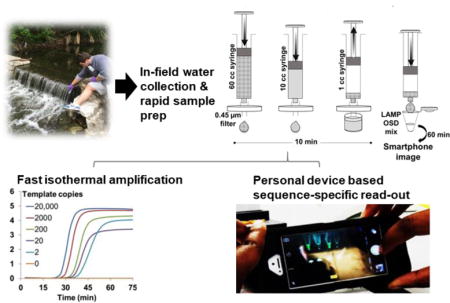

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Since human fecal contamination is a major health and environmental threat (Gasalla and Gandini 2016, Given et al. 2006, Wear and Thurber 2015), vigilant monitoring of water quality is increasingly required. Culture-based methods are available for determining the quantity of fecal indicating bacteria (FIB) (Harwood et al. 2014) but these methods are slow and often lack the diagnostic information necessary to identify the source. Faster methods relying on immunomagnetic FIB separation followed by adenosine triphosphate quantitation have been explored (Zimmer-Faust et al. 2014). However, distinguishing the original source of fecal pollution is crucial in devising appropriate control, prevention and risk management practices. To address this need a number of molecular diagnostic technologies have been developed that allow for host identification (Ahmed et al. 2007, Bernhard and Field 2000, Chase et al. 2012, Gourmelon et al. 2007, Graves et al. 2007, Kildare et al. 2007, Martellini et al. 2005, Newton et al. 2013, Newton et al. 2011, Peed et al. 2011, Reischer et al. 2007, Shanks et al. 2006, Viau and Boehm 2011). These methods are useful due to their high levels of precision, specificity, and sensitivity. For instance, the HF183/BFDrev and HumM2 quantitative PCR (qPCR) methods perform well for tracking human-sourced fecal pollution (Haugland et al. 2010, Layton et al. 2013, Shanks et al. 2010). Molecular diagnostic techniques have been helpful in determining best management practices in complicated watersheds (for examples see references (Riedel et al. 2015) and (Ervin et al. 2014)). However, successfully implementing PCR/qPCR requires expensive equipment and expertise typically only available in centralized testing facilities necessitating sample shipment and associated lengthy turnaround time and high cost per test per sample.

Isothermal nucleic acid amplification methods, such as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), can potentially rival PCR for sensitivity, but in a simplified format, since they do not require thermocycling (Boyle et al. 2013, de Paz et al. 2014, Rohrman and Richards-Kortum 2012). However, field use has often been limited by the propensity of isothermal methods like LAMP to be overrun by non-specific amplicons leading to false positive results (Abbasi et al. 2016, Kuboki et al. 2003, Tomita et al. 2008). In our previous work, we overcame spurious LAMP signals by applying principles of nucleic acid strand exchange circuitry (Chakraborty et al. 2016, Seelig et al. 2006, Yin et al. 2008, Zhang et al. 2007) to develop oligonucleotide strand displacement (OSD) probes that, like TaqMan probes in PCR, sequence-specifically transduce LAMP amplicons into a readable signal (Jiang et al. 2015). OSD probes are short, hemiduplex DNAs in which the short, single-stranded region in the longer strand acts as a toehold that hybridizes to complementary sequences in LAMP amplicon loops and initiates strand exchange (Zhang and Seelig 2011), ultimately resulting in hybridization of the longer, fluorophore-labeled strand to the LAMP loop and concomitant displacement of the quencher-labeled strand. The ensuing, real-time fluorescence accumulation allows OSDs to sequence-specifically report single- or multiplex accumulation of LAMP amplicons from tens to a few hundred nucleic acid molecules with minimal interference from non-specific amplicons or inhibitors (Bhadra et al. 2015). This innovation significantly enhanced the diagnostic applicability of LAMP by allowing it to match not only the sensitivity but also the specificity of real-time PCR.

The EPA-approved HF183 TaqMan qPCR assay is one of the best performing methods designed to distinguish human fecal contamination in environmental water by identifying genetic signatures from human-specific bacterial clusters belonging to the genus Bacteroides (Boehm et al. 2013, Nshimyimana et al. 2014, Riedel et al. 2014). These bacteria are ideal genetic identifiers of fecal source because they are restricted to warm-blooded animals and are present in significant numbers in feces (Hayashi et al. 2002). Moreover, they have a limited potential to re-grow in the environment due to their anaerobic lifestyle (Balleste and Blanch 2010). Although, the HF183 qPCR provides discriminating information its widespread use in water quality monitoring is difficult due to the technical expertise and expensive instruments required for execution. We surmised that we could leverage the excellent human fecal specificity demonstrated by the HF183 signature sequence and create a portable inexpensive molecular assay for in-field use to aid and expand water quality monitoring.

In the present work, we demonstrate a field ready human fecal diagnostic based on a LAMP-OSD assay intentionally designed to target the same human-specific Bacteroides sequence cluster also targeted by the HF183 TaqMan qPCR (Green et al. 2014). To enhance portability and minimize cost we have reduced equipment needs by eliminating reagent cold chain, utilizing simple and rapid sample preparation methods with syringe filters, reaction warming with commercially available hand warmers, and reading the output using unmodified smartphones. We test the detection limit and off-target reactivity of this HF183-LAMP-OSD system and demonstrate its robust performance with a variety of environmental water sources including artificial seawater and water contaminated with humic acids.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Chemicals and Oligonucleotides

All chemicals were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise indicated. All enzymes and related buffers were purchased from New England Biolabs (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). All oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table T1) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA, USA).

2.2 Design of LAMP primers and OSD reporter

LAMP primers were generated using the web-based Primer Explorer v5 primer design software (Eiken, Tokyo, Japan). Design of LAMP primers targeting human-specific HF183 signature sequence or dog fecal bacterial signatures was constrained to use previously described priming and probing regions for TaqMan qPCR assays (Boehm et al. 2013, Dick et al. 2005, Green et al. 2014, Kildare et al. 2007, Shibata et al. 2010). For instance, Primer Explorer v5 was constrained to use the HF183 qPCR forward primer (HF183F) as the inner primer F2 region when designing LAMP primer sets for human-associated HF183 sequences. Six primer sets generated by Primer Explorer, four sets targeting the human-specific HF183 sequences and two sets targeting dog fecal Bacteroides, were selected for functional testing by real-time LAMP measured using EvaGreen intercalation. One primer set each (Supplementary Table T1) that amplified the fewest template copies with minimal non-specific amplification was selected for assay development. In the HF183primer set, the B2 region of BIP was complementary to sequences that partially overlap HF183 qPCR reverse primer BFDRev and TaqMan probe BFDFam binding sites. The F1 region of FIP and B1 region of BIP bound to target sequences intervening the HF183F and BFDRev qPCR primer binding sites. The HF183 LAMP assay was subsequently appended with a fifth loop primer designed to bind to the loop sequence between the F2 and F1c regions of the amplicon.

An OSD probe was designed to also recognize the same target region as the BacR287 HF183 qPCR primer, a reverse primer demonstrated to improve the performance of HF183 qPCR, and the BFDFam (BthetP1) HF183 qPCR TaqMan probe (Green et al. 2014). The OSD probe specifically undergoes toehold-mediated strand exchange with the HF183 LAMP loop sequence intervening the B1 and B2c regions and was designed using our previously published design rules and the NUPACK software suite (Jiang et al. 2015, Zadeh et al. 2011). Briefly, a 33 nucleotide long OSD strand (Reporter F) and its complementary 22 nucleotide long OSD strand (Reporter Q) were designed to form a hemiduplex DNA that displayed a single-stranded toehold of 11 bp at the 5′-end of Reporter F. The 3′-end of Reporter F was labeled with fluorescein while the 5′-end of Reporter Q displayed an Iowa Black FQ quencher moiety. The 3′-end of the Reporter Q strand was blocked against polymerase-mediated extension by incorporation of an inverted dT modification.

LAMP-OSD assay for the E. coli uspB gene (Supplementary Table T1) was designed de novo using the same web-based tools for primer and probe design as outlined above. Primer design was constrained to include 40 to 60 bp loop regions for hybridization to OSD probes.

2.3 Plasmid construction

Target sequences for HF183, uspB and dog fecal LAMP were purchased as gene blocks from IDT. These gene blocks were cloned into pCR2.1TOPO plasmid (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) by Gibson assembly using the 2X Gibson assembly master mix from NEB and the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting HF183 plasmid is called pHF183 for this study. All plasmids used in this study were verified by sequencing at the Institute of Cellular and Molecular Biology Core DNA Sequencing Facility. DH10b E. coli transformed with these plasmids either were used directly as amplification targets or were subjected to plasmid purification.

2.4 LAMP assay with real-time signal measurement

HF183 LAMP reaction mixtures containing different amounts of template, 0.8 μM each of BIP and FIP primers, 0.2 μM each of B3 and F3 primers, 1 M betaine, and 0.4 mM deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs) were prepared in a total volume of 24 μl of 1X Isothermal Buffer (NEB; 20 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1% Tween® 20, pH 8.8 at 25°C) containing an additional 2 mM of MgSO4. In five-primer LAMP assays 0.4 μM of the loop primer was also included. Amplification reactions intended for measurement using dye intercalation were appended with 1X EvaGreen (Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA). These reactions were heated to 95 °C for 5 to 10 min and then subjected to primer annealing by chilling on ice for 2 min. This was followed by addition of 1 μl (8 units) of Bst 2.0 DNA polymerase to achieve the final assay volume of 25 μl. Subsequently, 20 μl of these LAMP reactions were transferred into 96-well PCR plates, which were incubated in a LightCycler 96 real-time PCR machine (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) maintained at 60 °C. Fluorescence signals were recorded every 3 min for 90 min followed by measurement of amplicon melting temperature.

In HF183 LAMP assays measured in real-time using OSD reporters, the intercalating dye EvaGreen was omitted. An OSD stock solution was prepared by annealing 10 μM Reporter F and 50 μM Reporter Q in 1X Isothermal Buffer. Annealing was achieved by incubating the solution at 95 °C for 5 min followed by slow cooling to room temperature at a rate of 0.1 °C/s. After annealing LAMP primers and templates, 1.5 μl of the annealed OSD probe (60 nM OSD Reporter F annealed with a 5-fold excess of Reporter Q) were added to the LAMP reactions along with 1 μl of the Bst 2.0 DNA polymerase enzyme. Subsequently, 20 μl of the LAMP-OSD solutions were transferred to 96-well PCR plates, which were maintained in a LightCycler 96 real-time PCR machine at 60 °C with fluorescence recording taken every 3 min.

The uspB LAMP-OSD assays were assembled in 25 μl of 1X Isothermal buffer (NEB) containing 0.4 μM each of F3 and B3, 0.8 μM of LP and 1.6 μM each of FIP and BIP primers, 0.4 mM dNTPs, 1M betaine, 2 mM additional MgSO4, 100 nM OSD reporter F strand annealed with 500 nM OSD reporter Q strand, and 16 units of Bst 2.0. Different colony forming units of E. coli bacteria spiked in water were added to these assays either directly or following 10 min thermal lysis at 95 °C; primer annealing step was omitted for both types of samples. For real-time signal measurement, LAMP reactions were transferred into 96-well PCR plates, which were incubated in a LightCycler 96 real-time PCR machine maintained at 65 °C. Fluorescence signals were recorded every 3 min for 90 min. Assays intended for endpoint readout were incubated for 90 min in a thermal cycler held at 65 °C followed immediately by fluorescence imaging with a smartphone camera as detailed below for the HF183 LAMP-OSD assay.

2.5 Visual readout and imaging of HF183 LAMP-OSD assay with smartphone camera

HF183 LAMP-OSD assay mixtures optimized for visualization with unaided human eyes and imaging with smartphones were assembled in 0.2 ml optically clear thin-walled tubes with low auto-fluorescence (Axygen, Union City, CA, USA). These 25 μl reactions were prepared by mixing different amounts of templates with 1.6 μM each of FIP and BIP, 0.8 μM of loop primer, 0.4 μM each of F3 and B3, 0.8 mM dNTPs, 1 M Betaine, OSD reporter (100 nM Reporter F annealed with 120 nM Reporter Q) and 16 units of Bst 2.0 DNA polymerase in 1X Isothermal buffer containing an additional 2 mM MgSO4. The primer annealing step was omitted and the reactions tubes were directly incubated for 1 h in a thermal cycler held at 60 °C. At the end of the incubation period OSD fluorescence was imaged using an unmodified iPhone 6 and an UltraSlim-LED transilluminator (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA).

In some experiments, fluorescence visualization and smartphone imaging were achieved with the aid of an imaging device (2.5 × 4 × 2.5 cm) designed and 3D printed in-house. The imaging device was designed with a completely removable lid that also served as the rack for holding LAMP-OSD reaction tubes for imaging. One Super Bright Blue 5 mm light emitting diode (LED) (Adafruit, New York, NY, USA) per assay tube slot was placed at the bottom of the imaging box such that its blue light would hit the assay tube in the slot from the bottom. An observation and imaging window was designed on one of the four faces of the cuboid device such that fluorescence emission could be captured at a 90° angle to the incident excitation source. Two cut-to-fit layers of inexpensive >500 nm bandpass orange lighting gel sheets (Lee Filters, Burbank, CA, USA) were attached to the observation window in order to filter the OSD fluorescence for observation.

In some experiments, the HF183 LAMP-OSD reaction tubes were incubated in a chemical incubation chamber created by placing two aerated hand warmer pouches (Hot Hands, Dalton, GA, USA) inside a small (6 × 6 × 2.5 cm) cardboard box lined with 6 mm thick layer of cork. Once the inside chamber temperature reached 60 °C, the LAMP-OSD reaction tubes were sandwiched in between the two hand warmer pouches. A small temperature probe was also inserted in the chamber prior to closing the lid in order to monitor the temperature, which steadily remained between 60 °C to 63 °C in replicate experiments. After 1 h of incubation, OSD fluorescence was imaged using an iPhone and an UltraSlim-LED transilluminator or the 3D printed imaging device.

2.6 HF183 TaqMan qPCR

A previously published TaqMan qPCR assay was used for HF183 quantitation (Green et al. 2014). Briefly, 0.093 μM BFDFam TaqMan probe, 1.2 μM BFDRev reverse primer and 1.2 μM HF183F forward primer were mixed with 1X FastStart Essential DNA Probes Master (Roche) and seeded with 6 μl water containing zero to several copies of purified synthetic templates or with 6 μl concentrated environmental sample. Following two pre-heating steps (2 min at 50 °C and 10 min at 95 °C) 50 cycles of two-step PCR amplification (15 sec at 95 °C followed by 1 min at 60 °C) and fluorescence measurement were performed using the LightCycler 96 real-time PCR machine.

2.7 Water sample processing

Water samples used for testing included: (i) artificial creek water (ACW: 1.3 mM K2HPO4, 1.7 mM KH2PO4, 7.9 mM NaCl), (ii) environmental water samples collected from a local creek (Waller Creek, Austin, TX, USA), a pond with resident fish and turtle populations, a fountain, a chlorinated swimming pool and municipal drinking water, (iii) artificial seawater (ASW: 450 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 9 mM CaCl2, 30 mM MgCl2.6H2O, 16 mM MgSO4.7H2O, pH 7.8), and (iv) municipal tap water containing 20% (w/v) or 2% (w/v) humic acid (Sigma). 50 ml water samples were either processed directly after collection or were spiked with different amounts of lab-grown recombinant E. coli pHF183 (bacterial colony counts were measured by plating a series of 10-fold dilutions on Luria Bertani agar plates containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin). In some experiments, ACW samples were spiked with primary filtered raw sewage (Walnut Creek Wastewater Treatment plant, Austin, TX, USA). Freshly collected sewage was stored at 4 °C and used within 6 h of collection. In off-target reactivity experiments, ACW was spiked with fresh feline or canine feces prior to processing for assays. Feces (0.464 g) from a single cat were dissolved in 50 ml ACW (CF0). 200 μl, 20 μl, and 2 μl of the CF0 sample were added into 50 ml ACW and tested by culturing on mTEC and mEI plates (see below) and by HF183 LAMP-OSD assays. Fresh sample (1.09 g) from either an individual dog feces (“1 dog”) or a mixture of nine dog feces (“9 dogs”) were mixed in 50 ml ACW (DF0). 500 μl, 200 μl or 20 μl of the DF0 sample were spiked into 50 ml ACW and tested by culturing on mTEC and mEI plates (see below) and by human and dog feces-distinguishing LAMP assays.

Nucleic acid amplification assays

Water samples were placed in 60 cc syringes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and manually filtered through a 0.45 μm pore size cellulose acetate syringe filter. Filters bearing the retentates, including microbial contaminants, were subsequently transferred to 1 cc syringes that were used to recover the retentate by back flushing the filters with 200 μl sterile water. For some water samples such as seawater and water contaminated with humic acids, the retentate-bearing filters were washed by flushing through 10 ml sterile water prior to retentate recovery via back flushing with 200 μl sterile water. Some 5 to 6 μl aliquots of these 200 μl recovered retentates were directly added to LAMP-OSD or TaqMan qPCR assays for assessing the presence or absence of fecal signature sequences.

Bacterial culture-based assays

E. coli and enterococci in water samples contaminated with primary raw sewage were enumerated by culturing on modified mTEC (membrane-thermotolerant Escherichia coli) and mEI (membrane Enterococcus indoxyl-β-D-glucoside) agar plates, respectively using published EPA protocols (EPA 2006, 2009). Briefly, 50 ml water samples were filtered through sterile 0.45 μm pore size 47 mm diameter grid-marked membrane filters using a vacuum filtration manifold. Filters were then removed from the filter housing and gently placed on mTEC or mEI plates and incubated according to their respective protocols.

2.8 HF183 LAMP-OSD lyophilization

Lyophilized HF183 LAMP-OSD assays were prepared by mixing 0.25 μl of glycerol-free Bst 2.0 (120 units/μl), 2.5 μl of annealed OSD reporter (1:1.2 uM Reporter F:Reporter Q strands), 2 μl of LAMP primer mix (5 μM each of F3 and B3, 20 μM each of FIP and BIP, 10 μM of loop primer), 5 μl of 4 mM dNTP mix and 1.25 μl of 1M trehalose. The mixture was frozen for 15 min at −80 °C and then lyophilized for 3 h using the VirTis Benchtop Pro lyophilizer (SP Scientific, Warminster, PA, USA). For determining storage stability, replicate lyophilized assays were stored at −20 °C, 25 °C and 42 °C. Lyophilized LAMP-OSD assays were functionally tested at various intervals by rehydrating with 25 μl solution containing different amounts of template, 1X Isothermal buffer, 1M betaine and 2 mM additional MgSO4.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Real-time qPCR data was analyzed using the LightCycler 96 software. Cq values for real-time LAMP-OSD assays were also determined using the LightCycler 96 software. For LAMP assays read at endpoint using a smartphone, samples were scored as detected when OSD fluorescence was visible after 60 minutes of amplification. For estimating the fewest template copies that can be detected using HF183 LAMP-OSD assays, seven replicate reactions at each template amount were analyzed in real-time assays while six replicates were imaged at endpoint using smartphones.

3. Results

3.1 HF183 LAMP-OSD assay design

A unique set of five LAMP primers (F3, B3, FIP, BIP and LP) and an OSD probe were designed to recognize eight different target sites within a 210 bp human fecal associated sequence that encompasses the 167 bp stretch detected by the HF183F/BFDRev TaqMan qPCR assay (Supplementary Figure S1). Since the LAMP-OSD and TaqMan qPCR assays use different primers, they could potentially target different populations of Bacteroides. To test this, we subjected the 210 bp target region to Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) analysis against Bacteroidales sequence database (Altschul et al. 1990). The outer initiation primers, F3 and B3, produce a 210 bp product. After the initiation step, the FIP and BIP primers exponentially amplify a 153 bp sub-section of the target. This 153 bp region is completely encompassed by the TaqMan qPCR 167 bp amplicon (Supplementary Figure S1) (Jiang et al. 2015). Some 67% of the first 1000 BLAST hits demonstrated 99% to 100% sequence similarity and would be detectable by both HF183 LAMP-OSD and by TaqMan qPCR (Supplementary Figure S1). 1% of the first 1000 hits were 97 % to 98% similar and hence should also be detectable by both assays. The remaining 32% of the top 1000 hits contained 4% to 6% sequence variation, which would likely eliminate reactivity with both HF183 TaqMan qPCR and LAMP-OSD assays. These results suggest that the HF183 LAMP-OSD assay will have a similar range of detection targets as the HF183/BFDRev TaqMan qPCR assay.

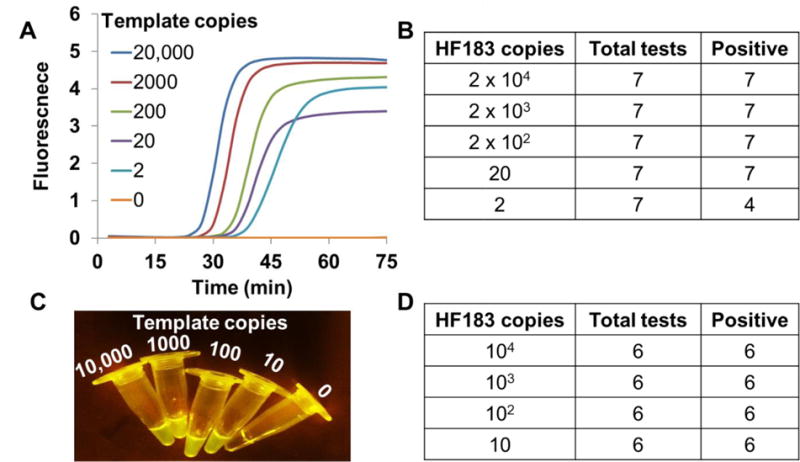

We functionally assessed this LAMP-OSD assay by challenging it with different copies of synthetic plasmids bearing the HF183 target sequence and measuring ensuing fluorescence in real-time using a PCR machine or at endpoint using a smartphone. Our results demonstrate that LAMP-OSD could always detect 10 to 20 copies of HF183 (Figure 1B and D), which is comparable to many HF183 TaqMan qPCR assays (Green et al. 2014). Amplifiable plasmid copy numbers were verified by parallel examination with qPCR using HF183F and BFDRev primers along with the BFDFam TaqMan probe (Supplementary Figure S2). Comparison of the real-time amplification kinetics of LAMP-OSD and TaqMan qPCR showed that, on average, the HF183 LAMP-OSD assay had a 35 min faster time-to-result compared to qPCR (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Detection of HF183 target DNA using LAMP-OSD assays.

Indicated copies of recombinant plasmids bearing the HF183 target sequence were amplified by HF183-specific LAMP-OSD assays. OSD fluorescence was measured in real-time (A and B) or imaged at endpoint using a smartphone (C and D).

Table. 1.

Time-to-result (Cq × time per cycle) for HF183 qPCR and LAMP-OSD.

| HF183 plasmid copies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection method | 2000 | 200 | 20 |

| qPCR | 66.1 ± 0.4 min | 73.1 ± 0.8 min | 78.3 ± 0.4min |

| LAMP-OSD | 31.6 ± 0.5min | 35 ± 2 min | 45 ± 6 min |

3.2 ‘Instrument-free’ HF183 LAMP-OSD assay for in-field use

In order to parse OSD fluorescence with minimal hardware we built a small (2.5 × 4 × 2.5 cm) 3D-printed imaging device containing 470 nm light emitting diodes (LEDs) (one per assay tube) for fluorescence excitation and a window covered with two layers of inexpensive >500 nm band pass orange gel filter for viewing and imaging fluorescence (Supplementary Figure S3). To maximize visual distinction of signal from background we optimized LAMP-OSD composition by increasing the amount of deoxyribonucleotides, primers, enzymes and OSD reporters. The resulting endpoint target-stimulated OSD fluorescence excited by a single LED in our imaging device is visible to human eyes and appears bright in smartphone camera images. Meanwhile, background signal in the absence of target amplicons remains below the detection limit of human eyes and smartphone CMOS cameras. To ensure that the simplification of assay readout does not compromise detection limit we assessed the limit of detection of the smartphone-imaged HF183 LAMP-OSD assay by amplifying different copies of HF183 target DNA. Our data (Figure 1C) indicate that as few as 10 copies of target DNA could be detected using smartphone imaging of optimized HF183 LAMP-OSD assays. Assay results were independent of variations in smartphone hardware and operating system (Supplementary Figure S3D).

To complement this simplification of assay readout using smartphones, we tested the usability of chemical heat for maintaining temperatures suitable for isothermal amplification.

Sandwiching the tubes between the two hand warmers produced uniform heating and also minimized the loss of volume due to evaporation and misplaced condensation (Supplementary Figure S3A). Following 60 min of incubation in this chemical heat chamber, the tubes were transferred to our fluorescence imaging device (Supplementary Figure S3B) and photographed using a smartphone. In the presence of HF183 targets, all assays produced bright fluorescence. Assays lacking specific templates remained dark (Supplementary Figure S3C).

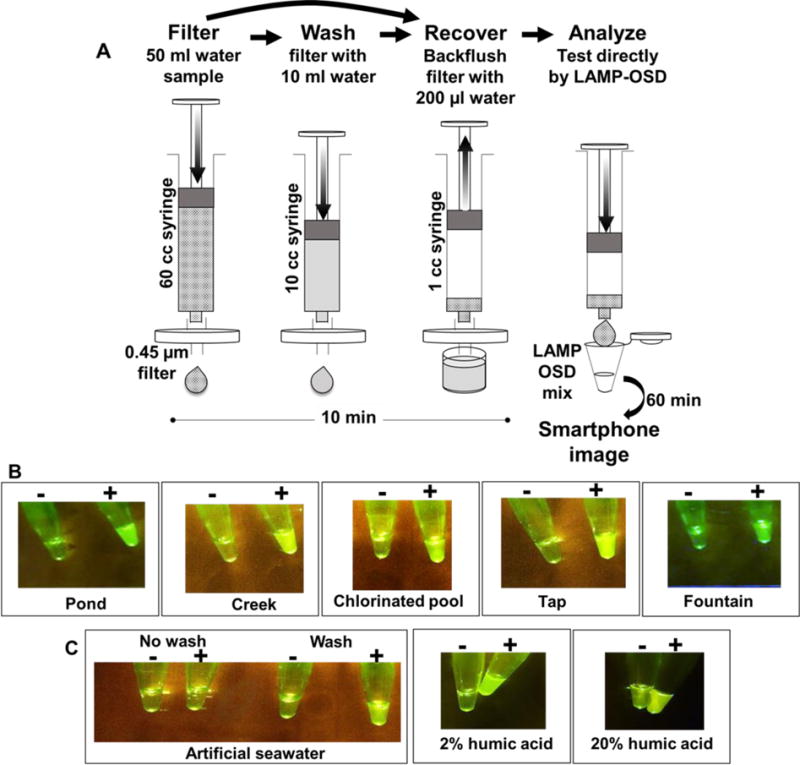

3.3 Rapid environmental water sample processing for direct HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis

A filtration based sample preparation method (see Section 2.7) was developed for in-field use (Figure 2A). To validate this two-step filter-back flush sampling methodology we prepared artificial creek water samples contaminated with known amounts of laboratory-grown recombinant E. coli harboring the HF183 target sequence. Subsequently, these water samples were processed using the filter-back flush methodology and 6 μl aliquots from the 200 μl of processed samples were assessed directly using HF183 LAMP-OSD assays. The high temperature required for LAMP is known to cause significant damage to bacterial structure (Mackey et al. 1991), thus enabling access to and amplification of the resident nucleic acid targets. Smartphone images revealed that 50 ml water samples contaminated with as few as 3.6 CFU/ml of recombinant E. coli pHF183 could be readily identified as contaminated (Supplementary Figure S4). These results indicate that the filter-back flush methodology is suitable for rapid processing of water samples for downstream LAMP-OSD analysis. Similar filtration approaches have been previously used successfully to rapidly purify bacteria such as Chlamydia trachomatis from infected cellular homogenates (Campbell et al. 1991).

Fig. 2. Rapid sample preparation and HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis of environmental and surrogate water samples.

(A) Schematic depicting sample preparation method. (B and C) Smartphone images depicting endpoint HF183 LAMP-OSD fluorescence in environmental water samples prepared using two-step (filter-back flush) sample processing method (B) and in surrogate water samples prepared using the three-step (filter-wash-back flush) processing method (C). All samples labeled ‘+’ were spiked with recombinant E. coli pHF183 prior to sample processing while samples labeled ‘−’ did not receive exogenous E. coli pHF183 contaminants.

We next sought to verify the universal applicability of our filter-back flush sampling methodology for processing recreational and environmental water samples of different origins and compositions. To that end, we collected several samples from a local creek, a pond, a fountain, a chlorinated swimming pool and municipal drinking water. A portion of these samples was subjected directly to filtration and back flushing followed by HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis. One creek water sample was positive for HF183 by both LAMP-OSD and by PCR suggesting the presence of human fecal contamination (Supplementary Figure S5). None of the remaining untampered water samples generated a positive HF183 LAMP-OSD signal. A second sample set of these environmental and drinking water sources that did not suffer natural human fecal contamination was analyzed following introduction of known numbers of laboratory-grown recombinant E. coli harboring HF183 target DNA (Figure 2B). When the water samples were spiked with as few as 19 colony forming units/ml of E. coli pHF183, we were able to clearly identify the contamination using our two-step filter-back flush sample preparation protocol followed immediately by LAMP-OSD analysis (Figure 2B). These results are suggestive of the suitability of our rapid sampling and isothermal diagnostic platform for analysis of many different environmental water samples.

To verify analytical compatibility with water laden with potential inhibitors we challenged our filter-back flush sample processing method with artificial seawater containing a high concentration of monovalent salts known to inhibit Bst DNA polymerase (Ong et al. 2015). Seawater contaminated with recombinant E. coli pHF183 failed to produce a positive LAMP-OSD signal (Figure 2C). We surmised that the LAMP-OSD assay might have been inhibited by excess salt introduced in the analyte upon back flushing the sample filter containing residual seawater. Therefore, we modified the protocol by washing the filter once with 10 ml of deionized water prior to back flushing the filter to collect the bacterial retentate for HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis. E. coli pHF183-contaminated artificial seawater samples subjected to this three-step sample processing comprising filtration and washing followed by retentate back flushing produced a clear positive signal upon HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis (Figure 2C). Three-step (filter-wash-back flush) sample processing is also efficient at reducing organic contaminants and allowing direct HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis of humic acid-containing water samples (Figure 2C).

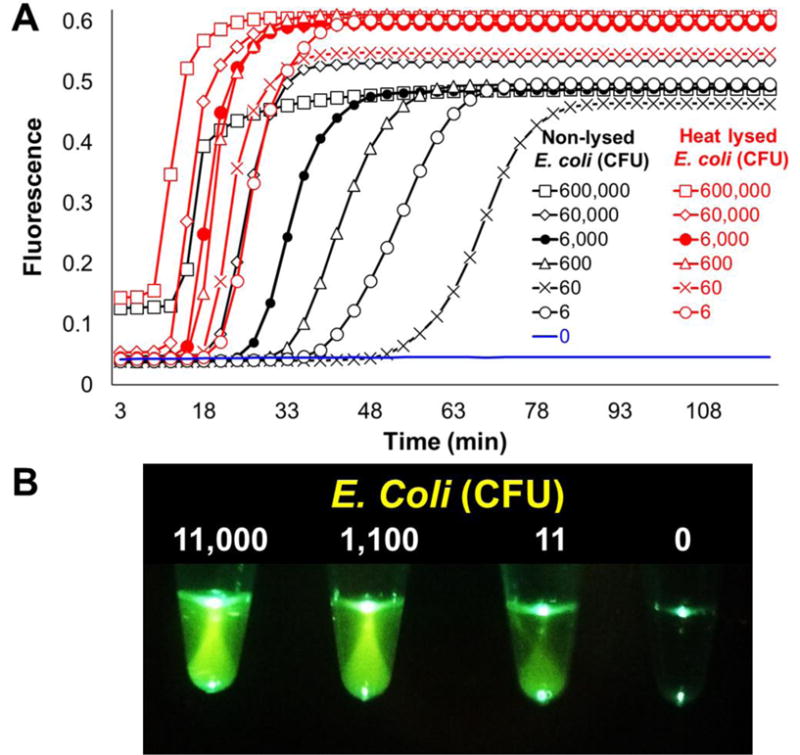

These results demonstrate that our simple and robust three step filtration-based sample processing approach integrated with the smartphone-read instrument-free one-pot HF183 LAMP-OSD assay (Figure 2A), is well suited for rapid inspection of a diversity of commonly encountered water samples without requiring complex and laborious nucleic acid purification steps. However, one caveat in these results is the use of pHF183 plasmid-bearing bacteria. Chromosomal targets might not be as readily accessible for amplification as plasmids without nucleic acid purification. Since HF183 Bacteroides cannot be easily cultured (Bae and Wuertz 2009), we engineered a new LAMP-OSD assay designed to amplify and detect a single copy E. coli chromosomal gene called uspB that encodes the universal stress protein B (Farewell et al. 1998). The uspB assay could readily detect the uspB marker in ≥6 CFU/reaction of E. coli (Figure 3). Thermal lysis of E. coli prior to assay reduced the time to detection. These observations suggest that HF183 chromosomal sequences in Bacteroides (a gram-negative bacterium like E. coli) should also be accessible for direct LAMP-OSD amplification and detection.

Fig. 3. Detection of endogenous bacterial genes using smartphone-imaged LAMP-OSD.

LAMP primers and OSD probes specific for the E. coli chromosomal gene uspB were used to identify E. coli spiked in water. (A) Indicated (6 × 105 to 6) colony forming units of E. coli were either added directly to uspB LAMP-OSD reactions (non-lysed E. coli) or subjected to heat lysis prior to LAMP-OSD analysis (heat-lysed E. coli). OSD fluorescence accumulation measured in real-time is depicted. (B) Smartphone-imaged uspB LAMP-OSD analysis of indicated colony forming units of non-lysed E. coli. Endpoint fluorescence was imaged after 90 min of LAMP amplification.

3.4 HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis of sewage-contaminated water

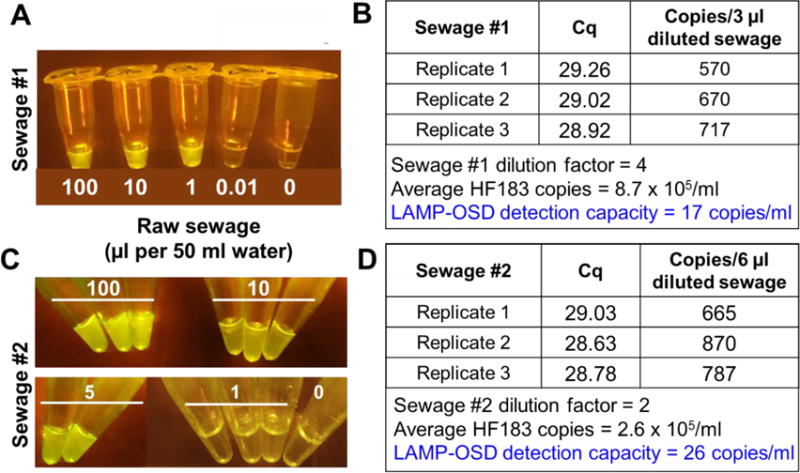

In order to assess the robustness of our sample processing and LAMP-OSD methodology in detecting actual human fecal contamination, instead of laboratory-cultured HF183 E.coli, we spiked 50 ml of sterile artificial creek water with different amounts of sewage. Primary raw sewage was collected on two separate occasions from the Walnut Creek Wastewater Treatment plant, one of two major plants in Austin, Texas, with a total permitted capacity of 150 million gallons per day. Sewage-contaminated water samples were filtered through 0.45 μm pore-size syringe filters followed by back flushing of the retentate in 200 μl of sterile water, of which 6 μl were directly analyzed by HF183 LAMP-OSD assay followed by endpoint imaging with a smartphone. Our results demonstrate that the HF183 LAMP-OSD assay could reliably detect the presence of as little as 1 μl and 5 μl of fresh primary sewage samples #1 and #2, respectively, in 50 ml of water samples (Figure 4). TaqMan qPCR analysis of the two sewage samples determined that sewage sample #1 contained 8.7 × 105 copies/ml of HF183 analytes while sewage #2 had 2.6 × 105 HF183 copies/ml (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S6). These amounts correlate well with reported estimates of ~2 × 105 to 8 × 105 HF183 copies/ml of sewage sampled from many different geographic areas (Ahmed et al. 2016, Boehm et al. 2015). This implies that our HF183 LAMP-OSD assay can easily detect as few as 17 to 26 HF183 copies/ml in sewage-contaminated water. These data suggest that our rapid sample processing methodology is efficient and the HF183 LAMP-OSD assay can robustly operate using crude samples without significant loss in detection limit.

Fig. 4. HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis of sewage-contaminated water.

Artificial creek water samples spiked with different amounts of two independently collected samples of primary raw sewage (A:Sewage #1 and C:Sewage #2) and processed by two-step filter back flush method were analyzed by HF183 LAMP-OSD assays. Smartphone images of OSD fluorescence at amplification endpoint are depicted. HF183 analytes in Sewage #1 and Sewage #2 samples were quantitated by HF183 TaqMan qPCR (B and D).

3.5 Off-target activity of HF183 LAMP-OSD assay

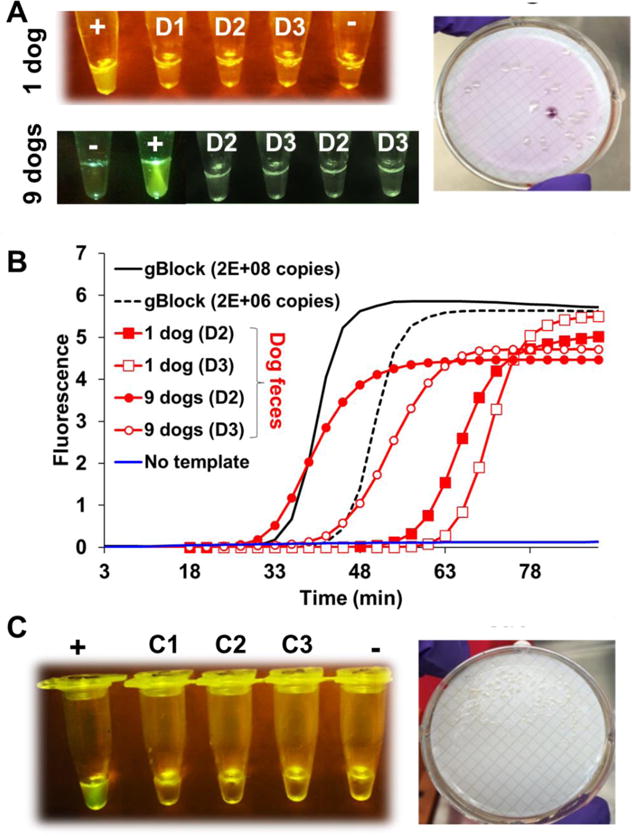

Since we engineered our HF183 LAMP-OSD assay to utilize many of the same priming and probing sequences responsible for the fecal source specificity of the HF183 TaqMan qPCR we expect our HF183 LAMP-OSD assay to demonstrate similar stringency for distinguishing human fecal contamination. To verify this we challenged the HF183 LAMP-OSD assay with different amounts of fresh feces collected from 10 canine and 1 feline pets. In this proof-of-concept study, we chose to test cross-reactivity with these two fecal sources because studies report dogs and cats to be among the primary sources of fecal contamination in urban watersheds (Schueler 1999). These artificially contaminated water samples contained viable fecal bacteria as illustrated by enumeration of fecal indicator E. coli and enterococci in duplicate water samples cultured on mTEC and mEI bacteriological media.

None of the HF183 LAMP-OSD assays seeded with canine or feline feces accumulated OSD fluorescence signal and hence remained as dark as the negative controls (Figures 5A and 5C). In contrast, positive control assays seeded with HF183 templates generated bright fluorescence. As a control to demonstrate the absence of inhibitors and the presence of amplifiable nucleic acids in these animal fecal samples we designed a LAMP assay to amplify Bacteroides molecular signatures previously used to design dog feces-specific qPCR assays (Boehm et al. 2013, Dick et al. 2005, Kildare et al. 2007, Shibata et al. 2010, Stewart et al. 2013). As seen in Figure 5B water samples contaminated with canine feces elicited a clear positive signal when tested with the dog-associated Bacteroides LAMP assay.

Fig. 5. HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis of non-human feces.

(A) Endpoint smartphone image of HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis (left panel) and exemplary mTEC plate culture (right panel) of dog feces (A) or cat feces (C) contaminated water. Feces from a single dog (“1 dog”) and an equal part mix of feces from multiple dogs (“9 dogs”) were independently tested. Water samples spiked with 500 μl (D1), 200 μl (D2), or 20 μl (D3) of dog feces containing samples or with 200 μl (C1), 20 μl (C2), or 2 μl (C3) of cat feces containing samples were processed by the two-step filter-back flush method. Tubes marked ‘+’ indicate positive control with pHF183 templates while tubes marked ‘−’ indicate negative control with no templates. (B) Real-time LAMP analysis of dog feces contaminated water samples (D2 and D3) using dog feces-specific primers. Negative control with no templates and positive control with gBlock templates are depicted in blue and black traces, respectively. Amplicon accumulation is indicated by increase in EvaGreen fluorescence.

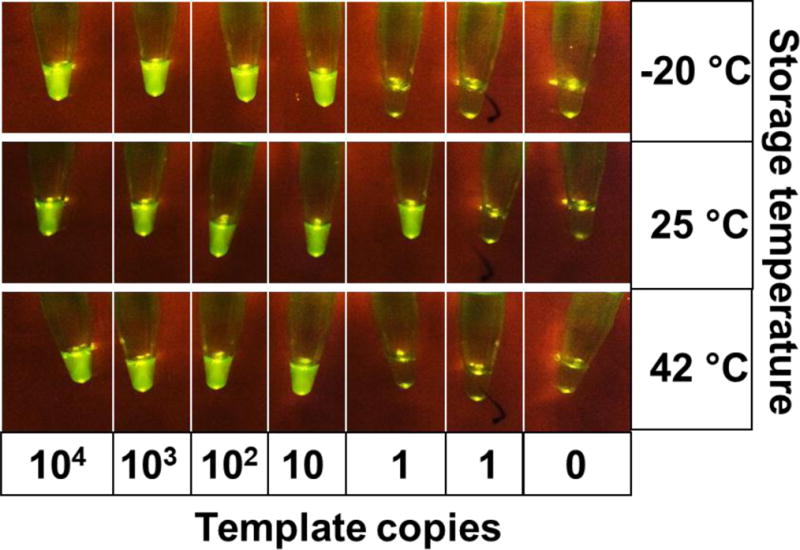

3.6 LAMP-OSD master mix lyophilization for storage without cold chain

Ready-to-use HF183 LAMP-OSD master mixes replete with enzymes, primers and OSD probes were stored at −20 °C for 60 days. There was no significant loss in amplification efficiency as evident from Cq values comparable to those obtained with freshly prepared assays (Supplementary Figure S7). These master mixes will greatly simplify rapid assessment of water samples however; ready-to-use assays that can be stably stored and shipped without cold storage are highly desirable for reducing operating costs and facilitating in-field use. Therefore, we lyophilized HF183 LAMP-OSD master mixes containing primers, OSD probes, deoxyribonucleotides, Bst 2.0 DNA polymerase and the stabilizer trehalose. Several sets of lyophilized assays stored at −20 °C, 25 °C or 42 °C were periodically tested for function by rehydration with 1X isothermal buffer containing magnesium and betaine. Even after 100 days of storage at temperatures as high as 42 °C the lyophilized HF183 LAMP-OSD assays efficiently amplified HF183 DNA targets resulting in accumulation of bright OSD fluorescence (Figure 6). No signal was obtained in the absence of specific targets. It should be noted that betaine and isothermal buffer are independently stable for long durations when stored without cold chain (Supplementary Figure S8). These results further bolster the point-of-need applicability of our HF183 LAMP-OSD assay system.

Fig. 6. Storage stability of lyophilized HF183 LAMP-OSD assay master mix.

Lyophilized assay master mixes were stored at the indicated temperature for 100 days. Smartphone image depicts endpoint OSD fluorescence upon HF183 LAMP-OSD analysis of indicated copies of HF183 templates using the lyophilized master mixes.

4. Discussion

Human fecal contamination in environmental waters is problematic due to the associated risk of disseminating hazardous pathogens and antibiotic resistance. The problem is further exacerbated by climate changes, natural and man-made disasters (Zolnikov 2013) and failing infrastructures. The need to invest in innovative diagnostic technologies for resource recovery and for monitoring pollution sources is well recognized (Young et al. 2015). High quality informative and actionable data is not only important for supporting the health of a water body but is key for guiding policy and investment towards best management practices. Development of new diagnostic approaches, education of the next generation of water professionals and facilitation of data collection are the keys to achieving global improvement in water quality (Young et al. 2015). Advanced qPCR-based molecular diagnostic methods to pinpoint sources of fecal contamination have been developed with the hope of achieving these goals. However, these methods need complicated instruments and highly trained operators. Unfortunately, infrastructure is expensive and there exists a severe gap in the technically trained human resource (Crocker et al. 2016, IWA 2014). These limitations have prevented widespread adoption of qPCR methods into water monitoring regimens.

We have developed a low-cost, rapid, easy-to-use platform technology for in-field detection of human fecal nucleic acid signatures in environmental and drinking water. Our technology effectively integrates the amplification power of LAMP and the sequence-specificity of DNA computational OSD probes to identify as few as 17 to 26 copies of Bacteroides HF183 sequences/ml, indicative of human feces, in minimally processed sewage-contaminated water samples with no cross-reactivity to dog or feline feces. Ancillary design details have been tailored to facilitate robustness, portability and widespread in-field use by reducing the need for expensive instruments, technical education and laborious user-required processes. These design details include: (i) minimization of procedural complexity – one-pot visually-readable assays directly analyze crudely concentrated samples without requiring nucleic acid purification; (ii) elimination of complex instruments or data analytics – visual ‘yes/no’ assay readout allows easy assessment of the presence or absence of contamination without; (iii) data accessibility – ability to capture LAMP-OSD signal with unmodified smartphones allows rapid data sharing through networks; and (iv) infrastructure cost reduction – lyophilized master mixes, storable without cold chain, reduce operation and distribution cost. These design innovations have also allowed us to achieve reliable sample-to-answer testing results within only 80 min of sampling. Not only is this a sizeable acceleration over current qPCR or culture-based tests that require several hours to days to produce results but due to the on-site applicability, our test also dismantles the time and monetary cost of sample storage and shipment.

One criticism that might be raised is the inability of HF183 LAMP-OSD to provide a quantitative determination of the level of contamination. To address this concern we have recently developed a robust, field-usable technology for semi-quantitative LAMP that enables reliable measurement of initial target copies on an order of magnitude scale via a simple, one-time determination of the presence or absence of visible OSD fluorescence at reaction endpoint (Jiang et al. 2017). OSD fluorescence amplitude is rendered a function of initial target copies by diverting replicative resources from these true targets to defined numbers of competing ‘false’ targets that display the same primer binding sites and amplification kinetics but lack OSD complementarity. We have successfully used these one-pot semi-quantitative LAMP-OSD reactions to directly and quantitatively estimate the numbers of HF183 nucleic acids in sewage, with the values obtained closely correlating with HF183 TaqMan qPCR quantitation (Jiang et al. 2017). Importantly, semi-quantitative HF183 LAMP-OSD reactions are amenable to endpoint readout via smartphone, unlike other methods such as qPCR that require continuous monitoring, and should therefore remain extremely useful for in-field water quality monitoring without any sophisticated instrumentation or informatics.

In ongoing efforts, we are expanding the test suite of the LAMP-OSD platform to allow more comprehensive fecal pollution tracking of non-human sources as well as direct detection of water-borne pathogens. Ultimately, the utility of the LAMP-OSD platform technology goes beyond water quality testing. The modular nature of the robust platform should allow rapid prototyping of sample processing methods and assays to detect almost any nucleic acid sequence signature in desired specimens.

5. Conclusions

We have developed a low-cost, easy-to-use molecular test to rapidly identify human fecal contamination in water by detecting as few as 17 copies/ml of human associated Bacteroides HF183 sequence with no off-target signal from dog or cat feces. This platform technology has low power requirements and is engineered for on-site sample-to-answer testing of minimally processed water samples without needing nucleic acid purification. As a result, our technology can bridge the gap in technically trained human resource by – (i) allowing citizen scientists with minimal expertise to actionably monitor water quality, and (ii) serving as a low cost easy-to-use teaching tool for educating the next generation of experts. We anticipate that these features would enhance adoption in routine monitoring and would be invaluable during emergencies presented by infrastructure failure and disruption. Unlike current bacteriological and molecular methods that require several hours to days to produce results rapid in-field generation of information would expedite action and allow individuals to lobby for improved water quality and affect water quality change in their communities.

Supplementary Material

A field ready isothermal assay for detection of human fecal contamination in water

DNA strand displacement probes guarantee assay specificity

Sample-to-answer detection in minimally processed environmental samples within 80 min

Smartphone assay readout, chemical heating and cold chain elimination reduce cost

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP 140108); the National Institutes of Health (R22512 and F31 DE024931); the NIH in conjunction with the Boston University (5U54EB015403-4500001623); the NIH in conjunction with Johns Hopkins University (131751); the Defense Health Agency (FAB-DW81XWH-0112-001); the Texas Health Catalyst Program at the Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin; the National Science Foundation (1417162001); and funding from the University of Texas College of Natural Sciences Freshman Research Initiative which is supported by two Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) grants (52005907 and 52006958).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting information

References

- Abbasi I, Kirstein OD, Hailu A, Warburg A. Optimization of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assays for the detection of Leishmania DNA in human blood samples. Acta Tropica. 2016;162:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W, Sidhu JPS, Smith K, Beale DJ, Gyawali P, Toze S. Distributions of Fecal Markers in Wastewater from Different Climatic Zones for Human Fecal Pollution Tracking in Australian Surface Waters. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2016;82(4):1316–1323. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03765-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W, Stewart J, Gardner T, Powell D, Brooks P, Sullivana D, Tindale N. Sourcing faecal pollution: A combination of library-dependent and library-independent methods to identify human faecal pollution in non-sewered catchments. Water Research. 2007;41(16):3771–3779. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae SW, Wuertz S. Discrimination of Viable and Dead Fecal Bacteroidales Bacteria by Quantitative PCR with Propidium Monoazide. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(9):2940–2944. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01333-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleste E, Blanch AR. Persistence of Bacteroides Species Populations in a River as Measured by Molecular and Culture Techniques. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(22):7608–7616. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00883-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard AE, Field KG. A PCR assay To discriminate human and ruminant feces on the basis of host differences in Bacteroides-Prevotella genes encoding 16S rRNA. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2000;66(10):4571–4574. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4571-4574.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra S, Jiang YS, Kumar MR, Johnson RF, Hensley LE, Ellington AD. Real-time sequence-validated loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays for detection of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm AB, Soller JA, Shanks OC. Human-Associated Fecal Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Measurements and Simulated Risk of Gastrointestinal Illness in Recreational Waters Contaminated with Raw Sewage. Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 2015;2(10):270–275. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm AB, Van De Werfhorst LC, Griffith JF, Holden PA, Jay JA, Shanks OC, Wang D, Weisberg SB. Performance of forty-one microbial source tracking methods: A twenty-seven lab evaluation study. Water Research. 2013;47(18):6812–6828. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle DS, Lehman DA, Lillis L, Peterson D, Singhal M, Armes N, Parker M, Piepenburg O, Overbaugh J. Rapid Detection of HIV-1 Proviral DNA for Early Infant Diagnosis Using Recombinase Polymerase Amplification. Mbio. 2013;4(2):pii, e00135–00113. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00135-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S, Yates PS, Waters F, Richmond SJ. Purification of Chlamydia trachomatis by a simple and rapid filtration method. Journal of General Microbiology. 1991;137(7):1565–1569. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-7-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty K, Veetil AT, Jaffrey SR, Krishnan Y. Nucleic Acid-Based Nanodevices in Biological Imaging. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2016;85(85):349–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase E, Hunting J, Staley C, Harwood VJ. Microbial source tracking to identify human and ruminant sources of faecal pollution in an ephemeral Florida river. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2012;113(6):1396–1406. doi: 10.1111/jam.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Shields KF, Venkataramanan V, Saywell D, Bartram J. Building capacity for water, sanitation, and hygiene programming: Training evaluation theory applied to CLTS management training in Kenya. Social Science and Medicine. 2016;166:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paz HD, Brotons P, Munoz-Almagro C. Molecular isothermal techniques for combating infectious diseases: towards low-cost point-of-care diagnostics. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 2014;14(7):827–843. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2014.940319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick LK, Bernhard AE, Brodeur TJ, Santo Domingo JW, Simpson JM, Walters SP, Field KG. Host distributions of uncultivated fecal Bacteroidales bacteria reveal genetic markers for fecal source identification. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(6):3184–3191. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3184-3191.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Escherichia coli (E coli) in Water by Membrane Filtration Using Modified membrane-Thermotolerant Escherichia coli Agar (modified mTEC) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2006. URL: https://nepis.epa.gov. Last accessed on September 11th, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Method 1600 Enterococci in Water by Membrane Filtration Using membrane Enterococcus Indoxyl-$-D-Glucoside Agar (mEI) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2009. URL: https://nepis.epa.gov. Last accessed on September 11th, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ervin JS, De Werfhorst LCV, Murray JLS, Holden PA. Microbial Source Tracking in a Coastal California Watershed Reveals Canines as Controllable Sources of Fecal Contamination. Environmental Science & Technology. 2014;48(16):9043–9052. doi: 10.1021/es502173s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farewell A, Kvint K, Nystrom T. uspB, a new sigmaS-regulated gene in Escherichia coli which is required for stationary-phase resistance to ethanol. Journal of Bacteriology. 1998;180(23):6140–6147. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6140-6147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasalla MA, Gandini FC. The loss of fishing territories in coastal areas: the case of seabob-shrimp small-scale fisheries in São Paulo, Brazil. Maritime studies. 2016;15(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- Given S, Pendleton LH, Boehm AB. Regional public health cost estimates of contaminated coastal waters: a case study of gastroenteritis at southern California beaches. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40(16):4851–4858. doi: 10.1021/es060679s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourmelon M, Caprais MP, Segura R, Le Mennec C, Lozach S, Piriou JY, Rince A. Evaluation of two library-independent microbial source tracking methods to identify sources of fecal contamination in french estuaries. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2007;73(15):4857–4866. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03003-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves AK, Hayedorn C, Brooks A, Hagedorn RL, Martin E. Microbial source tracking in a rural watershed dominated by cattle. Water Research. 2007;41(16):3729–3739. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green HC, Haugland RA, Varma M, Millen HT, Borchardt MA, Field KG, Walters WA, Knight R, Sivaganesan M, Kelty CA, Shanks OC. Improved HF183 Quantitative Real-Time PCR Assay for Characterization of Human Fecal Pollution in Ambient Surface Water Samples. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2014;80(10):3086–3094. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04137-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood VJ, Staley C, Badgley BD, Borges K, Korajkic A. Microbial source tracking markers for detection of fecal contamination in environmental waters: relationships between pathogens and human health outcomes. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2014;38(1):1–40. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugland RA, Varma M, Sivaganesan M, Kelty C, Peed L, Shanks OC. Evaluation of genetic markers from the 16S rRNA gene V2 region for use in quantitative detection of selected Bacteroidales species and human fecal waste by qPCR. Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 2010;33(6):348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, Benno Y. Phylogenetic analysis of the human gut microbiota using 16S rDNA clone libraries and strictly anaerobic culture-based methods. Microbiology and Immunology. 2002;46(8):535–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IWA. Avoidable Crisis An: WASH Human Resource Capacity Gaps in15 Developing Economies. The international Water Association. 2014 URL: http://www.iwa-network.org/downloads/1422745887-an-avoidable-crisis-wash-gaps.pdf. Last accessed on September 11th, 2017.

- Jiang YS, Bhadra S, Li B, Wu YR, Milligan JN, Ellington AD. Robust strand exchange reactions for the sequence-specific, real-time detection of nucleic acid amplicons. Anal Chem. 2015;87(6):3314–3320. doi: 10.1021/ac504387c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang YS, Stacy A, Whiteley M, Ellington AD, Bhadra S. Amplicon Competition Enables End-Point Quantitation of Nucleic Acids Following Isothermal Amplification. Chembiochem. 2017 doi: 10.1002/cbic.201700317. (doi: 10.1002/cbic.201700317.), doi: 10.1002/cbic.201700317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kildare BJ, Leutenegger CM, McSwain BS, Bambic DG, Rajal VB, Wuertz S. 16S rRNA-based assays for quantitative detection of universal, human-, cow-, and dog-specific fecal Bacteroidales: A Bayesian approach. Water Research. 2007;41(16):3701–3715. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboki N, Sakurai T, Di Cello F, Grab DJ, Suzuki H, Sugimoto C, Igarashi I. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for detection of African trypanosomes. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(12):5517–5524. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5517-5524.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton BA, Cao YP, Ebentier DL, Hanley K, Balleste E, Brandao J, Byappanahalli M, Converse R, Farnleitner AH, Gentry-Shields J, Gidley ML, Gourmelon M, Lee CS, Lee J, Lozach S, Madi T, Meijer WG, Noble R, Peed L, Reischer GH, Rodrigues R, Rose JB, Schriewer A, Sinigalliano C, Srinivasan S, Stewart J, Van De Werfhorst LC, Wang D, Whitman R, Wuertz S, Jay J, Holden PA, Boehm AB, Shanks O, Griffith JF. Performance of human fecal anaerobe-associated PCR-based assays in a multi-laboratory method evaluation study. Water Research. 2013;47(18):6897–6908. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey BM, Miles CA, Parsons SE, Seymour DA. Thermal-Denaturation of Whole Cells and Cell Components of Escherichia-Coli Examined by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Journal of General Microbiology. 1991;137:2361–2374. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-10-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martellini A, Payment P, Villemur R. Use of eukaryotic mitochondrial DNA to differentiate human, bovine, porcine and ovine sources in fecally contaminated surface water. Water Research. 2005;39(4):541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton RJ, Bootsma MJ, Morrison HG, Sogin ML, McLellan SL. A Microbial Signature Approach to Identify Fecal Pollution in the Waters Off an Urbanized Coast of Lake Michigan. Microbial Ecology. 2013;65(4):1011–1023. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0200-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton RJ, VandeWalle JL, Borchardt MA, Gorelick MH, McLellan SL. Lachnospiraceae and Bacteroidales Alternative Fecal Indicators Reveal Chronic Human Sewage Contamination in an Urban Harbor. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2011;77(19):6972–6981. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05480-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nshimyimana JP, Ekklesia E, Shanahan P, Chua LHC, Thompson JR. Distribution and abundance of human-specific Bacteroides and relation to traditional indicators in an urban tropical catchment. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2014;116(5):1369–1383. doi: 10.1111/jam.12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J, Evans TC, Tanner N. DNA polymerases. 13/600,408.(US 13/600,408) Patent Application number US. 2015

- Peed LA, Nietch CT, Kelty CA, Meckes M, Mooney T, Sivaganesan M, Shanks OC. Combining Land Use Information and Small Stream Sampling with PCR-Based Methods for Better Characterization of Diffuse Sources of Human Fecal Pollution. Environmental Science & Technology. 2011;45(13):5652–5659. doi: 10.1021/es2003167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reischer GH, Kasper DC, Steinborn R, Farnleitner AH, Mach RL. A quantitative real-time PCR assay for the highly sensitive and specific detection of human faecal influence in spring water from a large alpine catchment area. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2007;44(4):351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.02094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel TE, Thulsiraj V, Zimmer-Faust AG, Dagit R, Krug J, Hanley KT, Adamek K, Ebentier DL, Torres R, Cobian U, Peterson S, Jay JA. Long-term monitoring of molecular markers can distinguish different seasonal patterns of fecal indicating bacteria sources. Water Research. 2015;71:227–243. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel TE, Zimmer-Faust AG, Thulsiraj V, Madi T, Hanley KT, Ebentier DL, Byappanahalli M, Layton B, Raith M, Boehm AB, Griffith JF, Holden PA, Shanks OC, Weisberg SB, Jay JA. Detection limits and cost comparisons of human- and gull-associated conventional and quantitative PCR assays in artificial and environmental waters. Journal of Environmental Management. 2014;136:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrman BA, Richards-Kortum RR. A paper and plastic device for performing recombinase polymerase amplification of HIV DNA. Lab on a chip. 2012;12(17):3082–3088. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40423k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schueler T. Microbes and Urban Watersheds: Concentrations, Sources, & Pathways. Series: Watershed Protection Techniques. Publisher: Center for Watershed Protection. 1999;3(1):554–565. [Google Scholar]

- Seelig G, Soloveichik D, Zhang DY, Winfree E. Enzyme-free nucleic acid logic circuits. Science. 2006;314(5805):1585–1588. doi: 10.1126/science.1132493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks OC, Nietch C, Simonich M, Younger M, Reynolds D, Field KG. Basin-wide analysis of the dynamics of fecal contamination and fecal source identification in Tillamook Bay, Oregon. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72(8):5537–5546. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03059-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks OC, White K, Kelty CA, Sivaganesan M, Blannon J, Meckes M, Varma M, Haugland RA. Performance of PCR-Based Assays Targeting Bacteroidales Genetic Markers of Human Fecal Pollution in Sewage and Fecal Samples. Environmental Science & Technology. 2010;44(16):6281–6288. doi: 10.1021/es100311n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata T, Solo-Gabriele HM, Sinigalliano CD, Gidley ML, Plano LR, Fleisher JM, Wang JD, Elmir SM, He G, Wright ME, Abdelzaher AM, Ortega C, Wanless D, Garza AC, Kish J, Scott T, Hollenbeck J, Backer LC, Fleming LE. Evaluation of conventional and alternative monitoring methods for a recreational marine beach with nonpoint source of fecal contamination. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(21):8175–8181. doi: 10.1021/es100884w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JR, Boehm AB, Dubinsky EA, Fong TT, Goodwin KD, Griffith JF, Noble RT, Shanks OC, Vijayavel K, Weisberg SB. Recommendations following a multi-laboratory comparison of microbial source tracking methods. Water Research. 2013;47(18):6829–6838. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita N, Mori Y, Kanda H, Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nature Protocols. 2008;3(5):877–882. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau EJ, Boehm AB. Quantitative PCR-based detection of pathogenic Leptospira in Hawai’ian coastal streams. Journal of Water and Health. 2011;9(4):637–646. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear SL, Thurber RV. Sewage pollution: mitigation is key for coral reef stewardship. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2015;1355:15–30. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P, Choi HM, Calvert CR, Pierce NA. Programming biomolecular self-assembly pathways. Nature. 2008;451(7176):318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature06451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K, Rose JB, Fawell J, Llop RG, Nguyen H, Taylor M. Risk Assessment as a Tool to Improve Water Quality and The Role of Institutions of Higher Education. United Nations-Water Annual International Zaragoza Conference 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh JN, Steenberg CD, Bois JS, Wolfe BR, Pierce MB, Khan AR, Dirks RM, Pierce NA. NUPACK: Analysis and design of nucleic acid systems. J Comput Chem. 2011;32(1):170–173. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DY, Seelig G. Dynamic DNA nanotechnology using strand-displacement reactions. Nat Chem. 2011;3(2):103–113. doi: 10.1038/nchem.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DY, Turberfield AJ, Yurke B, Winfree E. Engineering entropy-driven reactions and networks catalyzed by DNA. Science. 2007;318(5853):1121–1125. doi: 10.1126/science.1148532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Faust AG, Thulsiraj V, Ferguson D, Jay JA. Performance and Specificity of the Covalently Linked Immunomagnetic Separation-ATP Method for Rapid Detection and Enumeration of Enterococci in Coastal Environments. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2014;80(9):2705–2714. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04096-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnikov TR. The Maladies of Water and War: Addressing Poor Water Quality in Iraq. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(6):980–987. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.