Abstract

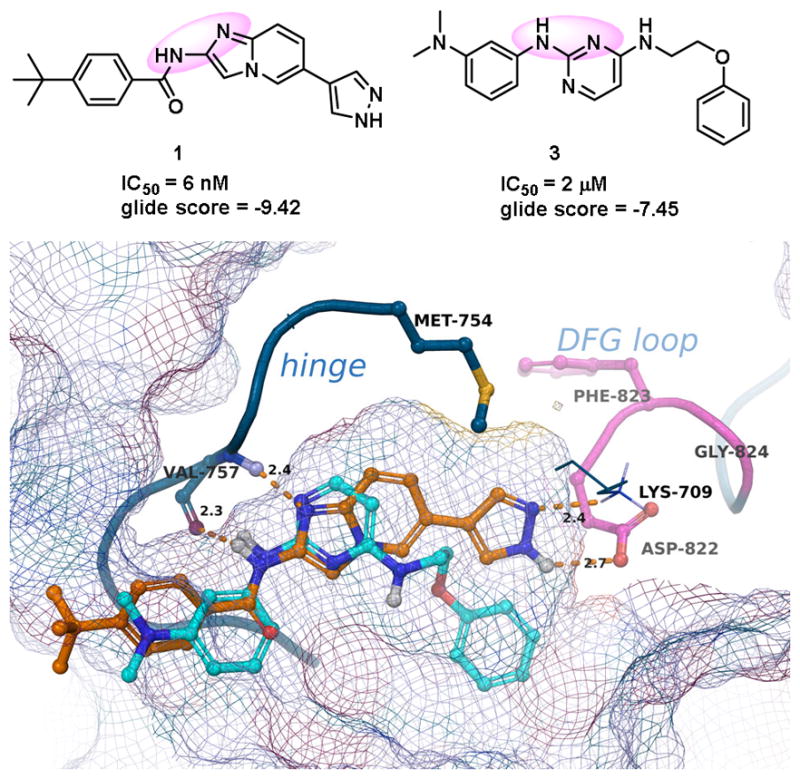

The development of a new series of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) inhibitors is described. Starting from purine, pyrimidine and quinazoline scaffolds identified by high throughput screening, we used tools of structure-based drug design to develop a series of potent kinase inhibitors, including 2-arylquinazoline derivatives 12 and 23, with submicromolar inhibitory activities against ASK1. Kinetic analysis demonstrated that the 2-arylquinazoline scaffold ASK1 inhibitors described herein are ATP competitive.

Keywords: Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK1), High throughput screening, Structure-based drug design, Kinase, Inhibitor

Graphical Abstract

The apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) is a serine/threonine protein kinase in the triple mitogen activated protein kinase (MAP3K) family that plays a critical role in the cellular response to a wide variety of environmental and biological stressors. Specifically, ASK1 is activated in response to increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, cytotoxic cytokines, and the activation of certain G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) agonists.1 ASK1 activates both the p38 MAP and the c-jun-N-terminal (JNK) kinase pathways, through activation of the MAP2Ks, MKK3/MKK6 and MKK4/MKK7 respectively.1 The MAPK signaling pathway is involved in a variety of fundamental cellular processes such as cell survival, growth, proliferation, differentiation, stress response, and apoptosis.2 As a result, ASK1 is activated in a number of human pathological conditions including cancer, autoimmune disease, diabetes, cardiac, inflammatory and several neurodegenerative diseases.3 Consequently, inhibition of ASK1 represents an attractive strategy to provide significant benefit in multiple stress-induced diseased states.

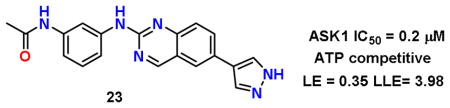

Several structural classes of ASK1 inhibitors, mostly from industry4 but also from academia5, have been identified over the last decade. In 2012, Terao et al (Takeda) reported imidazo[1,2-α]pyridine 1 (Fig. 1) as a potent ASK1 inhibitor derived from structure-based drug design.4b GSK,6 Merck7 and Gilead8 revealed some of their efforts on ASK1 a few years later. Although several series of ASK1 inhibitors have been identified, there are only a few reports of in vivo studies of these analogues.8 Specifically, Gilead has progressed a small molecule ASK1 inhibitor (GS-4997, selonsertib, compound 2, Fig. 1) into the clinic with mixed results. While the Phase II studies in pulmonary arterial hypertension and diabetic kidney disease failed to reach primary end points, the Phase II studies for GS4779 in nonalchololic steatoheaptitis (NASH) demonstrated improvement in primary endpoints, including improvements in liver fibrosis and reduction in progression to cirrhosis, prompting further Phase III studies. An earlier compound (GS-9679), also from Gilead, demonstrated pre-clinical efficacy in models of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury,9 acetaminophen (APAP) induced liver injury10 and diabetic nephropathy.11

Figure 1.

Structures of Takeda’s imidazo[1,2-α]pyridine (1) ASK1 inhibitor and clinical candidate GS-4997 (2, Gilead)

Herein, we present our efforts using high-throughput screening (HTS) and structure-based design that led to the identification and development of 2-arylquinazolines as a new ASK1 inhibitor scaffolds.

In order to identify new small molecules to inhibit ASK1, we developed and performed a HTS campaign of a proprietary focused kinase inhibitor library using a novel amplified luminescent proximity homogenous (Alphascreen) assay.12 HTS was carried out at the Scripps Florida HTS Facility on a subset of the Scripps Drug Discovery Library (SDDL) containing 16,000 drug-like compounds based on known kinase inhibitor scaffolds. The compounds were screened in a 384-well format through an in vitro assay using the purified stress-activated ASK1 signalosome complex, and monitoring the phosphorylation of its full-length native substrate, MKK6, as previously described.12 Compounds were analyzed at a single concentration of 7.5 μM (0.6% DMSO) using 7.5 μM staurosporine, a promiscuous ATP-competitive inhibitor, as a positive control. The ASK1 HTS campaign demonstrated an average fourfold signal to background (S/B) and Z′ factor (0.6±0.07) for the entire primary screen indicative of a robust asasay.12

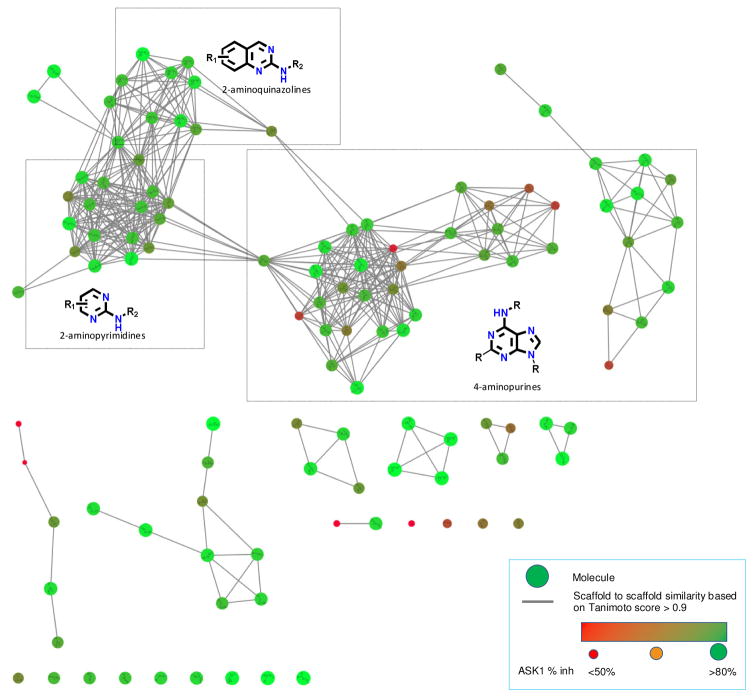

A total of 114 confirmed hits showed more than 40% inhibition of ASK1 (average of two runs) at 7.5 μM. The 27 analogues, that displayed more than 90% inhibition, were validated (in triplicate) using an orthogonal assay and the primary assay was used to determine the IC50’s of these compounds. In parallel, we analyzed structural features of all 114 initial hits and clustered them into different scaffolds using the Bemis-Murcko algorithm.13 This method dissects molecules into ring systems, linker, framework, and side chain atoms. The chemical structure similarity network graph and the ASK1 potencies were visualized in Cytoscape (v 3.4.0) using the Y-files organic layout method (Fig. 2).14 Many of the 114 hits were classified into several large clusters with unique scaffolds while others are present as singlets. We identified a series of new ASK1 inhibitors from six different structural classes (purine, pyridine, pyrimidine, triazine, benzo-fused pyrimidine, and quinazoline) with biochemical IC50 activities against ASK1 ranging from 0.3 to 10 μM. Out of the six structural classes, purines, as well as 2-aminoquinazolines and the related 2-aminopyrimidines formed the largest clusters (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Chemical structure similarity network graph and ASK1 potencies of the 114 primary screen hits. Topologically similar hits cluster together in organic fashion. Hits were abstracted to scaffolds using Murcko algorithm in order to construct the graph. Each of the screening hits is represented as a node, and nodes are connected via edges according to scaffold similarity (Tanimoto coefficient > 0.9). Molecular nodes are coded to reflect potency against ASK1 (small, red - inhibition < 50%; large, green - inhibition > 80%).

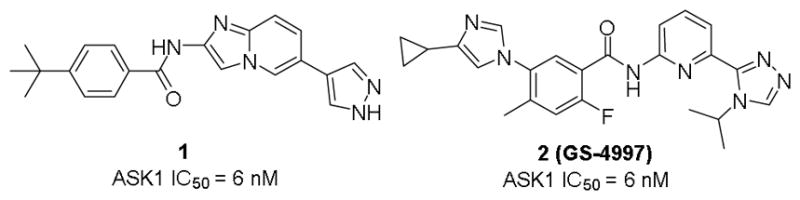

In order to understand the structural basis of observed ASK1 activity, we performed molecular docking studies using coordinates of the ASK1•1 (PDB ID:4BHN4b) crystal complex. Receptor grids were generated using Glide 7.415 in standard precision (SP) mode, without any constraints and validated by docking 1 and 2 into the kinase ATP binding site. The docked model for 1 was in good agreement with the reported crystal structures coordinates. The binding poses and scores of the top 27 screening hits (>90% inhibition) were subsequently analyzed in comparison to the known ASK1 inhibitors 1 and 2. Of these, HTS hit 3 adopted a binding pose featuring hydrogen bond interactions with the hinge residue Val757 that closely matched those of the Takeda inhibitor (Fig. 3). The hinge binding regions of 1 and 3 are highlighted with purple circles in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Hinge binding regions of 1 and 3 highlighted with purple circles (upper panel). Comparative docking of 1 (orange) and 3 (cyan). H-bond interactions with Val757, Lys709 and Asp822 are shown (lower panel).

Because 3 is approximately 250-fold less active as an ASK1 inhibitor compared to 1, additional inhibitors were designed with the intent to (i) maintain the hinge-binding interactions with Val757 highlighted in Fig. 3 and (ii) to gain interactions with Lys709 and Asp822 which are achievable with compound 1 but are predicted not to occur with 3. A set of inhibitors were synthesized, by incorporating structural units present in other hits from the HTS campaign. These inhibitors fall into two top “enriched” scaffold groups from the HTS (Fig. 2): compounds with pyrimidine or quinazoline cores; and compounds with purine cores.

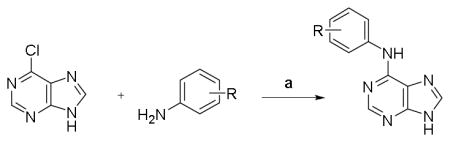

Guided by the molecular modeling results, we initially focused on the purine series of ASK1 inhibitors that showed superior docking and Glide scores. A selected number of examples from this exercise with logD values from 1.0 to 2.3 are shown in Table 1. The general procedure that was utilized for their synthesis relies on nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) reactions of the indicated, readily commercially available heterocycles.16 Unfortunately, none of the synthesized compounds presented in Table 1 showed activity in the ASK1 biochemical assay.

Table 1.

Summary of ASK1 activity and physico-chemical properties for selected number of purine series of inhibitors

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R | ASK1b IC50 (μM) |

logDc |

| 4 | H | > 10 | 1.74 |

| 5 | 4-F | > 10 | 1.88 |

| 6 | 3-Cl | > 10 | 2.34 |

| 7 | 3-NHAc | > 10 | 0.97 |

| 8 | 3-NMe2 | > 10 | 1.84 |

Reagents and conditions: DIPEA, 2-propanol, 90 °C, 18h, 35–80% yield.

Measured in triplicates using developed Alphascreen assay12

Calculated with Pipeline Pilot workflow application (Accelrys) at pH 7.4.

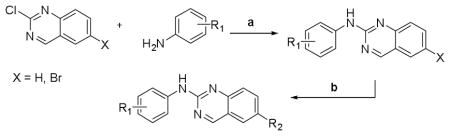

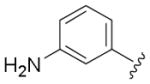

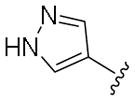

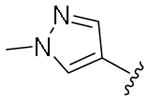

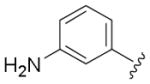

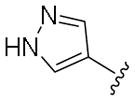

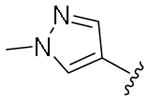

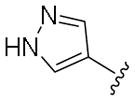

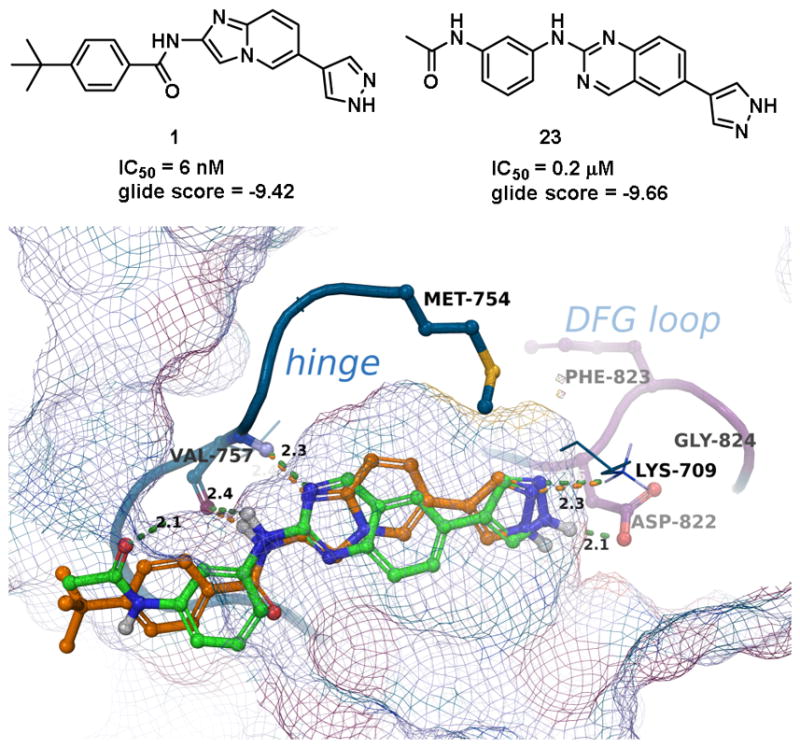

Next, a set of 2-arylquinazolines analogues was synthesized via nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) followed by Pd-mediated cross-coupling (Suzuki)17 reactions starting from commercially available 2-choloro-6-bromo-qunazoline. The summary of the quinazoline scaffold structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies is summarized in Table 2. First, a small number of monosubstituted 2-arylquinazolines 10–13 with logD values from 2.7 to 4.2 were synthesized and tested. Molecular docking studies suggested the possibility of picking up additional hinge binding interactions with the side chain of Gln756 upon the introduction of an appropriate hydrogen bond donor-acceptor unit. Gratifyingly, 3-acetamide analogue 12 showed a >10 fold improvement in potency (IC50 = 0.9 μM) in comparison to the initial quinazoline 9. We then extended the scaffold towards the DFG loop with the intent to gain favorable hydrogen bond interactions with Lys709 and Asp822. However, none of the 2-aryl-6-bromo-qunazolines 14–18 synthesized were active against ASK1. Installation of 3-aminophenyl (19), 1H-pyrazol-4-yl (20) and 1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl (21) at the C6 position of the unsubstituted 2-arylquinazoline also resulted in no potency improvement (IC50 > 10 μM). At the same time, incorporating the 3-acetamide unit (12) into the C6 1H-pyrazol-4-yl (20) led to identification of the most active compound in this series, 23 (IC50 = 0.2 μM). The predicted binding mode of 23 compared to Takeda 1 is presented in Fig. 4. As can be seen from this image, 23 is predicted to maintain the favorable interactions with Val-757 in the hinge binding region, but also to pick up favorable interactions with Lys-709. 3-N-phenylacetamide showed superior activity in comparison to other substituents such as anilines (25–27) and aryl halogens used for aromatic substitution reaction. Interestingly, the N-phenylpivalamide analogues (28, 29), that were predicted by molecular docking software to achieve favorable interactions in the outer, solvent-exposed pocket, did not show improvement in ASK1 activity. At the same time, on the phenyl side of the quinazoline, the presence of hydrogen-bond donor (i.e. 1H-pyrozole) is absolutely required to maintain kinase activity.

Table 2.

Summary of ASK1 activity and physico-chemical properties for selected number of purine series of inhibitors

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R1 | R2 | ASK1c IC50 (μM) |

logDd |

| 9 | H | H | > 10 | 3.54 |

| 10 | 3-Cl | H | > 10 | 4.15 |

| 11 | 4-F | H | > 10 | 3.69 |

| 12 | 3-NHAc | H | 0.9 | 2.78 |

| 13 | 3-NH2 | H | > 10 | 2.71 |

| 14 | H | Br | > 10 | 4.31 |

| 15 | 4-F | Br | > 10 | 4.46 |

| 16 | 3-NHAc | Br | > 10 | 3.55 |

| 17 | 3-NH2 | Br | > 10 | 3.48 |

| 18 | 3-NHPiv | Br | > 10 | 5.35 |

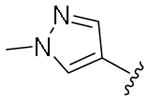

| 19 | H |

|

> 10 | 4.36 |

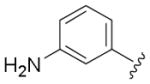

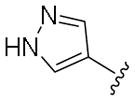

| 20 | H |

|

> 10 | 3.50 |

| 21 | H |

|

> 10 | 3.62 |

| 22 | 3-NHAc |

|

> 10 | 3.60 |

| 23 | 3-NHAc |

|

0.2 | 2.73 |

| 24 | 3-NHAc |

|

> 10 | 2.86 |

| 25 | 3-NH2 |

|

> 10 | 3.53 |

| 26 | 3-NH2 |

|

0.6 | 2.67 |

| 27 | 3-NH2 |

|

> 10 | 2.79 |

| 28 | 3-NHPiv |

|

> 10 | 4.53 |

| 29 | 3-NHPiv |

|

> 10 | 4.66 |

Reagents and conditions: (a)DIPEA, 2-propanol, 90 °C, 18h, 15–65% yields. (b) R2B(OH)2, Pd(Ph3P)4, sodium carbonate aq, dioxane:water (2:1), MW 110 °C, 30 min, 65–85% yields.

Measured in triplicates using developed Alphascreen assay12

Calculated with Pipeline Pilot workflow application (Accelrys) at pH 7.4

Figure 4.

Comparative docking of 1 (orange) and 23 (green). H-bond interactions with Val757, Lys709 and Asp822 are shown.

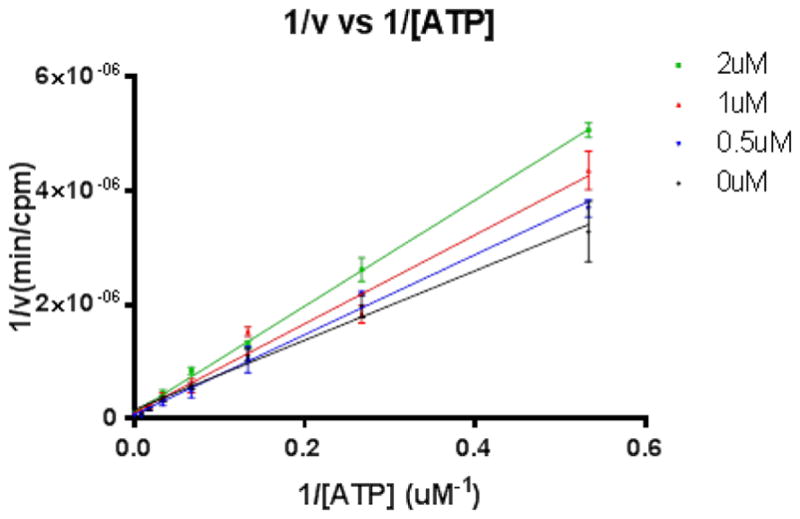

In order to confirm the ATP competitive nature of the 2-arylquinazolines, we have performed detailed enzyme kinetic studies with compound 12. The results of the experiment were visualized using a Lineweaver–Burk plot based on six different concentrations of ATP, with or without compound 12. As with any competitive inhibition where Vmax stays unchanged with increased Km values when the inhibitor concentration was raised, 12-mediated inhibition of ASK1 activity is an ATP competitive (Fig. 5, also supporting information). Inhibition of ASK1 activity by compound 12 in ATP competitive manner in combination with the molecular modeling studies of the 2-arylquinazolines binding in the active site of ASK1, strongly suggest that other analogues, including 23, bind to the kinase in a similar fashion.

Figure 5.

ASK1 inhibition by 2-arylquinazoline 12 is ATP competitive.

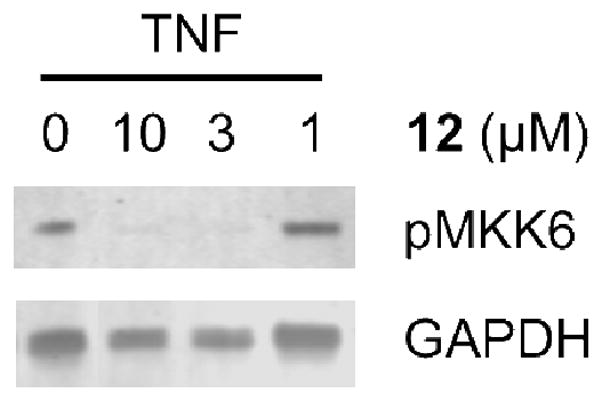

To determine the cell-based activity of our new analogues, we monitored the endogenous levels of the ASK1 downstream substrate, MKK6, under stress-induced conditions. This assay is designed to specifically measure the phosphorylation of endogenous MKK6 at Ser207 (MKK6ser207). Notably, ASK1−/− mice provide significant protection from injury in models of type 1 diabetes induced by streptozotocin and in β-cells from the pancreas by tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα).4b Using the rat INS-1e cell line we demonstrated that compound 12 protects against TNFα-induced MKK6ser207 phosphorylation (Fig. 6). These results confirm ASK1 activation in response to TNFα treatment.

Figure 6.

Immunoblot showing reduction of p-MKK6ser207upon treatment with 12 in INS1e cells

In addition to testing inhibitory activity against ASK1 and the cell-based substrate (MKK6) phosphorylation, three of our best compounds from the 2-arylquinazoline series (12, 23 and 26) were taken forward to a core set of ADME assays (solubility, microsome stability, inhibition of cytochrome P450 1A2, 2C9, 2D6, and 3A4) to assess the drug-like properties of the increasingly optimized candidates. The ADME data is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

ADME properties of selected ASK1 inhibitors series of inhibitors

| Cmpd | Solubility (μM)a | Microsome stability (min) (H/M/R)b | CYP inhibition (%)c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A2 | 2C9 | 2D6 | 3A4 | |||

| 12 | 100 | 6 / 2 / 4 | 94 | 20 | 13 | −13 |

| 23 | 10 | 42 / 2 / 4 | 49 | 98 | 52 | 88 |

| 26 | 17 | 29 / 2 / 3 | 67 | 93 | 56 | 52 |

| sunitinib | 46 /13 30 | |||||

Solubility in pH 7.4 phosphate buffered saline.

Microsome stability using human, mouse and rat liver microsomes, with sunitinib as the reference, minutes.

Cytochrome P450 inhibition assay, percentage of inhibition.

While all three inhibitors showed moderate to excellent aqueous solubility (10–100 μM), compounds were particularly unstable in the hepatic microsomal stability assay (especially in rodent liver microsomes, 2–4 min). The CYP inhibition profile of 23 (>85% inhibition of CYPs 2C9 and 3A4 at 10 μM) also indicates that further improvements are required. We suspect that the pyrazole unit of 23 is responsible for the CYP inhibition, as 12 exhibits <20% inhibition of 2C9 and 3A4 at 10 μM. Additional molecular modeling, design and structure refinement are underway to address these ADME liabilities.

In summary, we have developed a new series of ASK1 inhibitors by optimization of a HTS-derived set of hits. These efforts led to identification of 2-arylquinalzolines 12 and 23 with submicromolar inhibitory activities against ASK1. A detailed enzyme kinetic study and molecular modeling both confirm the ATP competitive nature of inhibition. This new series of ASK1 inhibitors displays a promising potency profile for further development as in vivo probes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NIGMS grant R01GM122109 (D.D. and W.R.).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.(a) Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, et al. Science. 1997;275:90. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen Z, Seimiya H, Naito M, et al. Oncogene. 1999;18:173. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McDonald PH, Chow CW, Miller WE, et al. Science. 2000;290:1574. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaeffer HJ, Weber MJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2435. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Hayakawa Y, Hirata Y, Sakitani K, et al. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:2181. doi: 10.1111/cas.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nagai H, Noguchi T, Takeda K, et al. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;40:1. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2007.40.1.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Okamoto M, Saito N, Kojima H, et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:486. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Terao Y, Suzuki H, Yoshikawa M, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:7326. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lanier M, Pickens J, Bigi SV, et al. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2017;8:316. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gibson TS, Johnson B, Fanjul A, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27:1709. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Volynets GP, Chekanov MO, Synyugin AR, et al. J Med Chem. 2011;54:2680. doi: 10.1021/jm200117h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Volynets GP, Bdzhola VG, Golub AG, et al. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;61:104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh O, Shillings A, Craggs P, et al. Protein Sci. 2013;22:1071. doi: 10.1002/pro.2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo X, Harada C, Namekata K, et al. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:504. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin JH, Zhang JJ, Lin SL, et al. Nephron. 2015;129:29. doi: 10.1159/000369152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Gerczuk PZ, Breckenridge DG, Liles JT, et al. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2012;60:276. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31825ea0fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Toldo S, Breckenridge DG, Mezzaroma E, et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e002360. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.002360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie Y, Ramachandran A, Breckenridge DG, et al. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;286:1. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tesch GH, Ma FY, Han Y, et al. Diabetes. 2015;64:3903. doi: 10.2337/db15-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sturchler E, Chen W, Spicer T, et al. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2014;12:229. doi: 10.1089/adt.2013.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bemis GW, Murcko MA. J Med Chem. 1996;39:2887. doi: 10.1021/jm9602928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, et al. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1739. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, et al. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6177. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Halgren TA, Murphy RB, Friesner RA, et al. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1750. doi: 10.1021/jm030644s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Zatloukal M, Gemrotová M, Doležal K, et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:9268. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bibian M, Rahaim RJ, Choi JY, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:4374. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.05.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2457. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.