Abstract

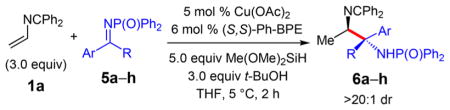

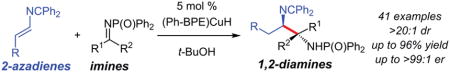

Here we report highly efficient and chemoselective azadiene–imine reductive couplings catalyzed by (Ph-BPE)Cu–H that afford anti-1,2-diamines. In all cases, reactions take place with either aldimine or ketimine electrophiles to deliver a single diastereomer of product in >95:5 er. The products’ diamines are easily differentiable, facilitating downstream synthesis.

Graphical Abstract

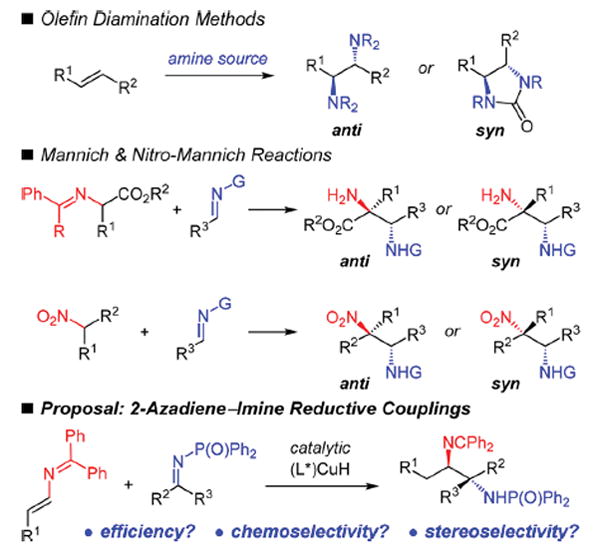

The catalytic enantioselective preparation of vicinal diamines is an important goal in synthetic chemistry owing to the large number of pharmaceuticals, natural products, and chiral ligands that contain this motif.1 Although several approaches to this moiety have been reported by a number of researchers, significant shortcomings in scope or the ability to differentiate the products’ two amino groups constrain their utility (Scheme 1). One major strategy has utilized intermolecular olefin diamination2 to afford either the anti- or syn-1,2-diamines.3 In nearly all such cases, the two introduced amino groups have identical substituents, making their differentiation challenging to achieve.4 Another strategy has employed N-substituted enolates or nitroalkanes in Mannich-type reactions;5–7 either diastereomer may be selectively formed. However, in the former case, the requirement of an electron withdrawing group reduces the scope of diamines that may be prepared. In the latter, nitro group reduction is needed to secure the diamine.8 In both cases, when tetrasubstituted amine-containing stereogenic centers are formed, one of that center’s other substituents has been limited to a carbonyl-like group.

Scheme 1.

Catalytic Enantioselective Methods for Preparing Vicinal Diamines and Proposed Strategy

To address these limitations, we sought to develop a method that would unite two N-containing reagents via catalytic enantioselective C–C bond formation such that (1) a greater diversity of 1,2-diamines, including those with N-containing tetrasubstituted stereogenic centers, might be garnered; (2) the nitrogen groups of the products would be easily differentiated in order to assist in subsequent derivatizations; and (3) either free amine could be obtained without the need for harsh reducing conditions. We envisioned that the reductive coupling of 2-azadienes9 and suitably activated imines could allow us to realize this goal (Scheme 1). However, catalytic enantioselective reductive couplings with imines are rare.10,11 Successful implementation of our proposed strategy would require high catalyst efficiency and control over diastereo-, enantio-, and chemoselectivity for the desired C–C bond formation (versus imine reduction12).

Within the last several years, enantioselective Cu-catalyzed reductive couplings13,14 of unsaturated hydrocarbons with various C-electrophiles has rapidly emerged as an effective way for preparing myriad chemical motifs, often comprised of vicinal stereogenic centers. Vinylarenes,10c,d,15 vinylboronic esters,16 allenes,11e,17 and conjugated enynes18 and dienes15g,18 have comprised the substrates for these processes, yet none has established vicinal heteroatom-substituted stereogenic centers. Our recent disclosure of the Cu-catalyzed reductive coupling of 2-azadienes and ketones shows the promise these reagents hold for achieving such a goal.9 In this work, we demonstrate that 2- azadienes participate in chemoselective Cu-catalyzed reductive couplings with N-diphenylphosphinoyl (Dpp) imines. Both aldimines and ketimines react to furnish anti-1,2-diamines19 with vicinal stereogenic centers, in most cases as a single stereoisomer. The two N-groups of the products, one an imine and the other a phosphinamide, are readily discriminated, enabling their subsequent divergent elaboration.

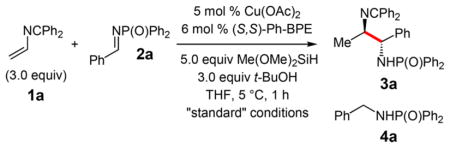

We initially explored addition of terminal 2-azadiene 1a to Dpp-aldimine 2a (Table 1). Optimal conditions employ 3.0 equiv of azadiene, DMMS as the reducing agent, t-BuOH as additive, a Cu-based catalyst with (S,S)-Ph-BPE as the ligand, and 5 °C (ice bath) reaction temperature (entry 1). After 1 h under these conditions, the desired diamine 3a can be obtained in 82% yield, solely as the anti-diastereomer and as a single enantiomer. Accompanying 3a is ca. 15% reduction product 4a. Utilizing imine activating groups other than Dpp (e.g., Ts, Boc, etc.) results in <2% conversion to 3a (entry 2).10d,12 Conducting the reaction at 22 °C results in poorer chemoselectivity, delivering more of the unwanted 4a; however, stereoselectivity remains unaffected (entry 3). Omitting t- BuOH not only lowers catalyst efficiency but also adversely affects chemoselectivity (entry 4), similar to observations made by the Buchwald lab in styrene–imine couplings.10d The identity of the alcohol additive is also critical for the selective formation of 3a (entry 5). Although an i-Pr-BPE–Cu complex fails to furnish any product (entry 6), switching to i-Pr- DuPHOS generates 3a in 40% yield, 10:1 dr, and 99:1 er but accompanied by a substantial quantity of 4a (entry 7). A QuinoxP-derived catalyst, although highly selective for C–C bond formation over imine reduction (8:1), generates 3a in only 4:1 dr (entry 8).20

Table 1.

Impact of Reaction Conditions in Azadiene–Imine Reductive Couplingsa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| entry | variation from the entry “standard” conditions | 3a:4ab | yield of 3a (%)c | drb | erd |

| 1 | none | 5:1 | 82 | >20:1 | >99:1 |

| 2 | Ts, Boc et al. instead of P(O)Ph2 | – | – | – | – |

| 3 | 22°C | 2:1 | 63 | >20:1 | >99:1 |

| 4 | not-BuOH | 0.8:1 | 14 | >20:1 | >99:1 |

| 5 | MeOH instead of t-BuOH | 1.5:1 | 50 | >20:1 | >99:1 |

| 6 | i-Pr-BPE instead of Ph-BPE | – | <5 | – | – |

| 7 | i-Pr-DuPHOS instead of Ph-BPE | 0.9:1 | 40 | 10:1 | 99:1 |

| 8 | QuinoxP instead of Ph-BPE | 8:1 | 59/16e | 4:1 | 99:1 |

Reaction under N2 with 0.1 mmol imine 2a.

Determined by 400 MHz 1H NMR spectroscopy of the unpurified mixture.

Isolated yield of purified 3a.

Determined by HPLC analysis of purified 3a major diastereomer.

Yield of the major/minor diastereomer of 3a.

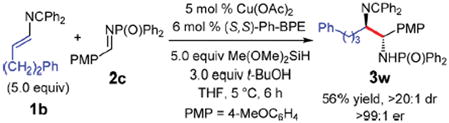

Several aldimines undergo coupling with azadiene 1a, leading to anti-diamines 3 as a single diastereomer (Table 2). In most cases, only a single enantiomer of product is generated. A variety of aryl-substituted imines participate in the reaction with the more electron rich substrates affording the highest yields (64–93%, entries 1–5, 13, 15). Halogen substituents are tolerated with diamines 3g–i and 3o isolated in 55–73% yield (entries 6–8, 14). More electron poor imines also yield the desired diamines 3j–l (entries 9–11) but in somewhat diminished yields (41–59%). The observed trend is due to increasingly competitive imine reduction as the imine partner becomes more electron deficient;21 however, boronic ester 3m is isolated in 75% yield as a single stereoisomer (entry 12). Notably, more sterically hindered aldimines do not affect reaction efficiency: o-tolyl 3p is furnished in 89% yield (entry 15). Heteroaryl aldimines can be coupled efficiently with the terminal azadiene as well to generate diamines 3q–s in 83– 94% yield (entries 16–18).

Table 2.

Aldimine Scope in Couplings with Azadiene 1a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| entry | product, R | yield (%)b | erc |

| 1 | 3b, 4-Me2NC6H4 | 96 | >99:1 |

| 2 | 3c, 4-MeOC6H4 | 89 | >99:1 |

| 3 | 3d, 4-F2HCOC6H4 | 64 | >99:1 |

| 4 | 3e, 4-MeSC6H4 | 82 | >99:1 |

| 5 | 3f, 4-(N-pyrazolyl)C6H4 | 84 | >99:1 |

| 6 | 3g, 4-FC6H4 | 73 | >99:1 |

| 7 | 3h, 4-ClC6H4 | 62 | >99:1 |

| 8 | 3i, 4-BrC6H4 | 64 | >99:1 |

| 9 | 3j, 4-MeO2CC6H4 | 59 | >99:1 |

| 10 | 3k, 4-F3CC6H4 | 44 | >99:1 |

| 11d | 3l, 4-NCC6H4 | 41 | >99:1 |

| 12e | 3m, 4-(pin)BC6H4 | 75 | >99:1 |

| 13 | 3n, 2-naphthyl | 85 | >99:1 |

| 14 | 3o, 3-BrC6H4 | 55 | >99:1 |

| 15 | 3p, 2-MeC6H4 | 89 | >99:1 |

| 16 | 3q, 3-furyl | 93 | >99:1 |

| 17 | 3r, 3-thiophenyl | 83 | >99:1 |

| 18 | 3s, 3-indolyl(NMe) | 94 | 98.5:1:5 |

| 19 | 3t, C(Me)CHPh | 71 | >99:1 |

| 20f | 3u, CHCHPh | 61 | >99:1 |

| 21 | 3v, CH2CH2Ph | 52 | >99:1 |

Reaction under N2 with 0.2 mmol imine 2. Dr measured by 400 MHz 1H NMR spectroscopy of the unpurified mixture.

Isolated yield of purified 3.

Determined by HPLC analysis of purified 3.

5.0 equiv 1a.

4.0 equiv 1a.

Formed as a 4:1 mixture of 3u:3v; yield of isolated 3u.

Unsaturated imines also undergo efficient coupling with azadiene 1a (entries 19 and 20). Allylic amine 3t, bearing a trisubstituted olefin, is formed in 71% yield. The less hindered cinnamyl 3u is isolated in 61% yield but the reductive coupling also affords ca. 15% of saturated diamine. An alkyl-substituted imine leads to 52% yield of saturated diamine 3v in >99:1 er (entry 21). An alkynyl aldimine failed to deliver the desired diamine product.

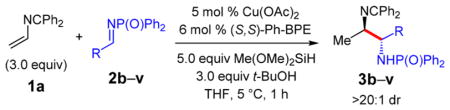

We also examined the coupling of 4-substituted 2-azadienes with aldimines to deliver diamines comprised of α-alkyl groups other than methyl. As typified in eq 1, the added steric hindrance of azadiene 1b leads to slower Cu–H insertion and a more competitive reduction, which adversely affects the diamine yield. An electron rich aldimine, such as 2c, and an extended reaction time (6 h) are required to obtain good yield of 3w. Increasing to 5.0 equiv of azadiene improves the reaction as well with the product then isolated in 56% yield (versus 42% with 3.0 equiv 1b), >20:1 dr, and >99:1 er.

|

(1) |

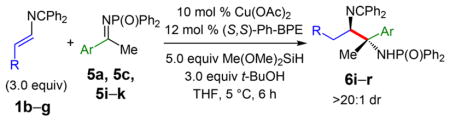

We next sought to test whether azadiene couplings with ketimines would enable the synthesis of 1,2-diamines wherein one stereogenic center is fully substituted. Reactions that form such motifs wherein both amines are bound to stereogenic centers, each with a variety of substituents, are rare and challenging to achieve. Therefore, we were pleased to find that terminal azadiene 1a reacts with aryl/alkyl and diaryl ketimines to generate diamines 6a–h in 84–92% yield (Table 3). With the exception of the less electrophilic, electron rich imine 5b (entry 2), which requires higher temperature and longer reaction time, reactions proceed efficiently at 5 °C within 2 h. Transformations occur with >98% chemoselectivity for the reductive coupling regardless of imine identity. Remarkably, in all cases, the diamines are obtained in >20:1 dr (entries 1–7) and with high enantioselectivity. Notably, in addition to tolerating several aryl groups, the coupling is also permissible with longer chain alkyl groups (entry 7). The sterically encumbered benzophenone imine reacts smoothly to give diamine 6h in 86% yield (entry 8).

Table 3.

Couplings of Azadiene 1a with Ketiminesa

Furthermore, ketimines also participate in reductive couplings with 4-substituted 2-azadienes, proceeding with ca. 60–70% chemoselectivity to furnish diamines 6i–r as a single diastereomer and with high enantioselectivity (Table 4). Despite the steric congestion, reactions proceed to completion within 6 h at 5 °C. Product yields are improved with 10 mol % catalyst loading.22 Variation of the ketimine’s aryl substituent, including both electron rich and electron poor arenes, is tolerated in couplings with azadiene 1b (entries 1–5). The azadiene may contain several functional groups, including heterocycles, ethers, esters, and halides that are preserved in the products (44–63% yield, entries 6–10). The versatility of the reaction partners should enable the assembly of a range of complex molecules from these diamine building blocks.

Table 4.

Addition of 4-Substituted Azadienes to Ketiminesa

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| entry | product, Ar, R | yield (%)b | erc |

| 1 | 6i, Ph, (CH2)2Ph | 62 | 96:4 |

| 2 | 6j, 4-MeO2CC6H4, (CH2)2Ph | 56 | 99:1 |

| 3 | 6k, 4-ClC6H4, (CH2)2Ph | 62 | >99:1 |

| 4 | 6l, 3,4-dioxolatoC6H3, (CH2)2Ph | 59 | 96:4 |

| 5 | 6m, 2-naphthyl, (CH2)2Ph | 72 | 98.5:1.5 |

| 6 | 6n, Ph, n-Bu | 54 | 95.5:4.5 |

| 7 | 6o, Ph, (CH2)2(3-thiophenyl) | 63 | 97.5:2.5 |

| 8 | 6p, Ph, (CH2)3OTBS | 53 | 96.5:3.5 |

| 9 | 6q, Ph, (CH2)4OBz | 56 | 97:3 |

| 10 | 6r, Ph, (CH2)4Cl | 44 | 96:4 |

Reaction under N2 with 0.2 mmol imine 5.

See Table 2.

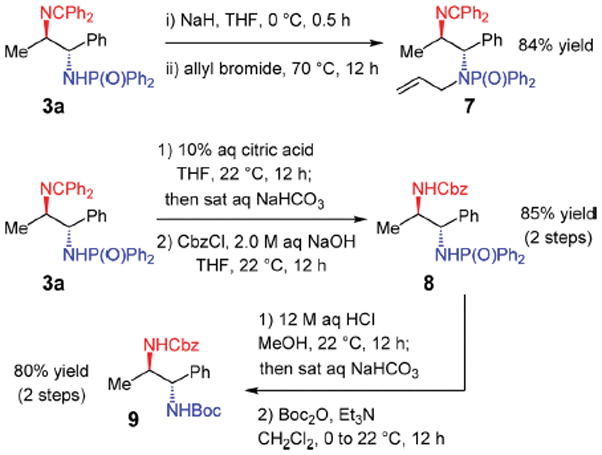

The developed azadiene–imine reductive couplings have the advantage that the amines within the products are readily differentiated (Scheme 2) as one is doubly protected as an imine (red) and the other monoprotected as the phosphinamide (blue). Either may be transformed to the amine by hydrolysis (i.e., without reduction). These qualities allow for selective functionalization of either product nitrogen. For example, deprotonation of the phosphinamide N–H of 3a enables alkylation to deliver 7 in 84% yield while retaining the imine. Alternatively, the imine may be hydrolyzed under mildly acidic conditions and the resulting free amine then functionalized, such as in the formation of benzyl carbamate 8 (85% yield over two steps). The phosphinamide may then be cleaved with stronger acid, enabling functionalization of the liberated amine: phosphinamide 8 is converted to t-butyl carbamate 9 in 80% yield (two steps).

Scheme 2.

Utilizing the Products’ Differentiated Amines

In this work, we have shown that reductive couplings of 2- azadienes with imines are an efficient and highly stereoselective way to construct vicinal diamines, several of which are difficult to access through existing protocols and have not before succumbed to enantioselective synthesis. The methodology represents a rare example of enantioselective reductive couplings of imines as well as Cu-catalyzed reductive couplings to set vicinal heteroatom-substituted stereogenic centers. Our future efforts will concentrate on the further development of azadienes and their applications to chiral amine synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for financial support of this research from the NIH (GM124286), ACS Petroleum Research Fund (56575- DNI1), and Duke University. We thank Dr. Roger Sommer (NC State) for X-ray crystallographic analysis.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b04750.

Data for C34H30BrN2OP (3i) (CIF)

Experimental procedures, analytical data for new compounds, and X-ray crystallographic data (PDF) NMR spectra (PDF)

References

- 1.For a review, see: Lucet D, Le Gall T, Mioskowski C. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1998;37:2580. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981016)37:19<2580::AID-ANIE2580>3.0.CO;2-L.

- 2.For a review on enantioselective olefin diamination, see: Zhu Y, Cornwall RG, Du H, Zhao B, Shi Y. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:3665. doi: 10.1021/ar500344t.For examples of enantioselective intermolecular reactions, see: Du H, Yuan W, Zhao B, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11688. doi: 10.1021/ja074698t.Du H, Zhao B, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8590. doi: 10.1021/ja8027394.Cornwall RG, Zhao B, Shi Y. Org Lett. 2013;15:796. doi: 10.1021/ol303469a.Muñiz K, Barreiro L, Romero RM, Martínez C. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:4354. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01443.

- 3.For ring-forming (intramolecular) enantioselective cases, see: Sequeira FC, Turnpenny BW, Chemler SR. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:6365. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003499.Ingalls EL, Sibbald PA, Kaminsky W, Michael FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:8854. doi: 10.1021/ja4043406.Turnpenny BW, Chemler SR. Chem Sci. 2014;5:1786. doi: 10.1039/C4SC00237G.Mizar P, Laverny A, El-Sherbini M, Farid U, Brown M, Malmedy F, Wirth T. Chem - Eur J. 2014;20:9910. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403891.Fu S, Yang H, Li G, Deng Y, Jiang H, Zeng W. Org Lett. 2015;17:1018. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00131.Wang FL, Dong XY, Lin JS, Zeng Y, Jiao GY, Gu QS, Guo XQ, Ma CL, Liu XY. Chem. 2017;3:979.

- 4.For intermolecular diaminations where the two amines may be differentiated, see: Simmons B, Walji AM, MacMillan DWC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:4349. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900220.Fu R, Zhao B, Shi Y. J Org Chem. 2009;74:7577. doi: 10.1021/jo9015584.

- 5.For a review on Mannich reactions with N-substituted nucleophiles, see: Arrayás RG, Carretero JC. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:1940. doi: 10.1039/b820303b.For enantioselective examples, see: Kobayashi S, Yazaki R, Seki K, Yamashita Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:5613. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801322.Hernández-Toribio J, Arrayás RG, Carretero JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16150. doi: 10.1021/ja807583n.Kano T, Sakamoto R, Akakura M, Maruoka K. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7516. doi: 10.1021/ja301120z.Zhang WQ, Cheng LF, Yu J, Gong LZ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:4085. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107741.Lin S, Kawato Y, Kumagai N, Shibasaki M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:5183. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412377.Kondo M, Nishi T, Hatanaka T, Funahashi Y, Nakamura S. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:8198. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503098.Kano T, Kobayashi R, Maruoka K. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:8471. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502215.

- 6.For enantioselective vinylogous Mannich reactions to prepare this motif, see: Ranieri B, Curti C, Battistini L, Sartori A, Pinna L, Casiraghi G, Zanardi F. J Org Chem. 2011;76:10291. doi: 10.1021/jo201875a.Silverio DL, Fu P, Carswell EL, Snapper ML, Hoveyda AH. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:3489. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.04.006.

- 7.For examples of enantioselective nitro-Mannich reactions, see: Yamada K-i, Harwood SJ, Gröger H, Shibasaki M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1999;38:3504. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991203)38:23<3504::aid-anie3504>3.0.co;2-e.Yamada K-i, Moll G, Shibasaki M. Synlett. 2001;2001:980.Knudsen KR, Risgaard T, Nishiwaki N, Gothelf KV, Jørgensen KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5843. doi: 10.1021/ja010588p.Nugent BM, Yoder RA, Johnston JN. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3418. doi: 10.1021/ja031906i.Yoon TP, Jacobsen EN. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:466. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461814.Singh A, Yoder RA, Shen B, Johnston JN. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3466. doi: 10.1021/ja068073r.Trost BM, Lupton DW. Org Lett. 2007;9:2023. doi: 10.1021/ol070618e.Singh A, Johnston JN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5866. doi: 10.1021/ja8011808.Uraguchi D, Koshimoto K, Ooi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10878. doi: 10.1021/ja8041004.Davis TA, Wilt JC, Johnston JN. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2880. doi: 10.1021/ja908814h.Handa S, Gnanadesikan V, Matsunaga S, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4925. doi: 10.1021/ja100514y.Sprague DJ, Singh A, Johnston JN. Chem Sci. 2018;9:2336. doi: 10.1039/c7sc05176j.

- 8.For other enantioselective approaches to vicinal diamines, see: Ooi T, Sakai D, Takeuchi M, Tayama E, Maruoka K. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:5868. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352658.Kitagawa O, Yotsumoto K, Kohriyama M, Dobashi Y, Taguchi T. Org Lett. 2004;6:3605. doi: 10.1021/ol048498n.Trost BM, Fandrick DR, Brodmann T, Stiles DT. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:6123. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700835.Arai K, Lucarini S, Salter MM, Ohta K, Yamashita Y, Kobayashi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8103. doi: 10.1021/ja0708666.Yu R, Yamashita Y, Kobayashi S. Adv Synth Catal. 2009;351:147.MacDonald MJ, Hesp CR, Schipper DJ, Pesant M, Beauchemin AM. Chem - Eur J. 2013;19:2597. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203462.Wu B, Gallucci JC, Parquette JR, RajanBabu TV. Chem Sci. 2014;5:1102.Uraguchi D, Kinoshita N, Kizu T, Ooi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:13768. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09329.Izumi S, Kobayashi Y, Takemoto Y. Org Lett. 2016;18:696. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03666.Chai Z, Yang PJ, Zhang H, Wang S, Yang G. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2017;56:650. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610693.Dumoulin A, Bernadat G, Masson G. J Org Chem. 2017;82:1775. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b03093.Mwenda ET, Nguyen HN. Org Lett. 2017;19:4814. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02256.Perrotta D, Wang MM, Waser J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2018;57:5120. doi: 10.1002/anie.201800494.

- 9.Li K, Shao X, Tseng L, Malcolmson SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:598. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For enantioselective examples, see: Ngai MY, Barchuk A, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12644. doi: 10.1021/ja075438e.Zhou CY, Zhu SF, Wang LX, Zhou QL. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10955. doi: 10.1021/ja104505t.Ascic E, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:4666. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02316.Yang Y, Perry IB, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:9787. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06299.For a related redox neutral process, see: Oda S, Franke J, Krische MJ. Chem Sci. 2016;7:136. doi: 10.1039/c5sc03854e.

- 11.For nonenantioselective examples, see: Townes JA, Evans MA, Queffelec J, Taylor SJ, Morken JP. Org Lett. 2002;4:2537. doi: 10.1021/ol020106u.Kong JR, Cho CW, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11269. doi: 10.1021/ja051104i.Komanduri V, Grant CD, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12592. doi: 10.1021/ja805056g.Zhu S, Lu X, Luo Y, Zhang W, Jiang H, Yan M, Zeng W. Org Lett. 2013;15:1440. doi: 10.1021/ol4006079.Liu RY, Yang Y, Buchwald SL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:14077. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608446.Lee KN, Lei Z, Ngai MY. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:5003. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01373.For related redox neutral processes, see: Schmitt DC, Lee J, Dechert-Schmitt AMR, Yamaguchi E, Krische MJ. Chem Commun. 2013;49:6096. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43463j.Chen TY, Tsutsumi R, Montgomery TP, Volchkov I, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1798. doi: 10.1021/ja5130258.Oda S, Sam B, Krische MJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:8525. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503250.

- 12.For enantioselective Cu-catalyzed imine hydrosilylation, see: Lipshutz BH, Shimizu H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:2228. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353294.

- 13.For Cu–H reviews, see: Rendler S, Oestreich M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:498. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602668.Lipshutz BH. Synlett. 2009;2009:509.Jordan AJ, Lalic G, Sadighi JP. Chem Rev. 2016;116:8318. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00366.

- 14.For reviews of catalytic reductive couplings with metals other than Cu, see: Montgomery J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:3890. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300634.Hassan A, Krische MJ. Org Process Res Dev. 2011;15:1236. doi: 10.1021/op200195m.Standley EA, Tasker SZ, Jensen KL, Jamison TF. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:1503. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00064.Nguyen KD, Park BY, Luong T, Sato H, Garza VJ, Krische MJ. Science. 2016;354:aah5133. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5133.Kim SW, Zhang W, Krische MJ. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50:2371. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00308.

- 15.(a) Saxena A, Choi B, Lam HW. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8428. doi: 10.1021/ja3036916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang YM, Bruno NC, Placeres AL, Zhu S, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:10524. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang YM, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:5024. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bandar JS, Ascic E, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:5821. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Friis SD, Pirnot MT, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:8372. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zhou Y, Bandar JS, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:8126. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b04937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Gui YY, Hu N, Chen XW, Liao LL, Ju T, Ye JH, Zhang Z, Li J, Yu DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:17011. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Gribble MW, Jr, Guo S, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:5057. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b02568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Han JT, Jang WJ, Kim N, Yun J. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:15146. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee J, Torker S, Hoveyda AH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2017;56:821. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai EY, Liu RY, Yang Y, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:2007. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y, Perry IB, Lu G, Liu P, Buchwald SL. Science. 2016;353:144. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For azaallyl anion additions to imines that afford syn-1,2- diamines, see: Chen YJ, Seki K, Yamashita Y, Kobayashi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3244. doi: 10.1021/ja909909q.Matsumoto M, Harada M, Yamashita Y, Kobayashi S. Chem Commun. 2014;50:13041. doi: 10.1039/c4cc06156j.

- 20.For additional screening data, see the Supporting Information.

- 21.See the Supporting Information for further details.

- 22.For example, with 5 mol % Cu and 6 mol % Ph-BPE, diamine 6i in Table 4, entry 1 is isolated in only 50% yield after 12 h.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.