Highlights

-

•

Retroperitoneal schwannomas are usually asymptomatic, rare neoplasms.

-

•

Diagnosis can only be achieved with surgical removal of mass.

-

•

Laparoscopy is the most useful therapeutic approach.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Schwannoma, tumor, Pelvic disease, Retroperitoneum

Abstract

Introduction

Single pelvic schwannomas are rare tumor arising from the retrorectal, lateral or obturatory space. Laparoscopic approach to schwannoma located in lateral pelvic space has been previously described only in one case report. We present a case of a successful laparoscopic resection of pelvic schwannoma emphasizing the advantages of such a minimal invasive approach.

Presentation of case

A 54-years-old, obese, male patient was admitted to our hospital referring dysuria and strangury. Abdominal CT scan showed a lateral pelvic well-circumscribed mass with smooth regular margins. A CT-guided fine needle biopsy resulted non-diagnostic. An elective laparoscopic resection was performed. The patient had a short, uneventful post-operative course. Pathological examination revealed a benign schwannoma.

Discussion

Using PubMed database, we reviewed the English language international literature using the MeSH terms “laparoscopic,” “minimally invasive” and “schwannoma”. We identified quite 20 previous cases of pelvic schwannomas removed by laparoscopy or robotic surgery. We found out that a preoperative diagnosis of these rare neoplasms is difficult to be obtained; in most cases, laparoscopic approach was successfully performed.

Conclusion

Despite it could not be proven yet, due to the rarity of this tumor, we agree with literature that laparoscopic removal of pelvic benign tumor may offer several advantages. The direct high-definition vision deeply into this narrow anatomical space, especially in obese patients, provides a detailed view that makes easier to isolate and spear the anatomical structures surrounding the tumor. Furthermore, the pneumoperitoneum may create the right plane of dissection, minimizing the risk of tumor rupture and bleeding.

1. Introduction

Schwannomas are tumors arising from peripheral Schwann cell and are typically solitary and benign neoplasms. Multiple schwannomas are extremely rare, developing exclusively as part of inherited disorder like Neurofibromatosis and Schwannomatosis.

Solitary Schwannomas commonly develop from the nerves of the head and neck district. Pelvic location with origin from sacral and hypogastric plexus is unusual (1–3% of all schwannomas) [1].

There are no specific clinical or radiological signs for pelvic schwannomas and in most cases the surgical excision has both diagnostic and therapeutic finality. However, this surgery can be hard to perform because of the narrow working space as well as the need to preserve the vascular and nervous plexus surrounding the tumour. First laparoscopic resection of a pelvic schwannoma has been reported in 1996 by Melvin [2]. From this report, only few other laparoscopic removal of such neoplasms has been described [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7]].

We present a successful laparoscopic resection of a pelvic schwannoma, located in the lateral space in an obese man. A literature review was also performed to discuss the advantage of the laparoscopic approach.

| The work has been reported in line with SCARE criteria [16]. |

2. Presentation of case

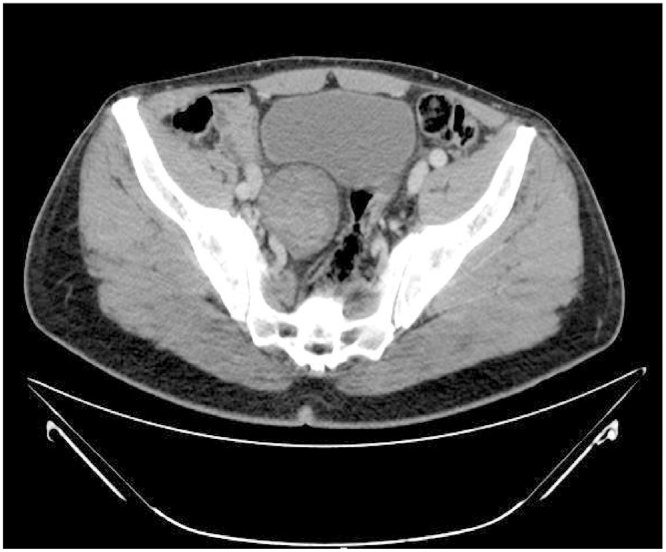

A 54-years-old, Caucasian, obese (BMI 36.7) male was admitted to our hospital referring dysuria and strangury. US scan showed an oval-shaped pelvic mass behind the bladder. Contrast enhanced-CT scans confirmed an hypodense solid mass of 5,8 × 5,6 × 5,4 cm (CC × AP × LL) with sharp and regular limits in the right pelvic space without sign of infiltration of surrounding structures (posterior wall of the bladder, the left internal iliac vessels, rectum, the first sacral vertebral body) (Fig. 1). Pancolonscopy and cystoscopy excluded the colic or bladder origin of the tumor. A CT-guided fine needle aspiration was performed but it resulted non-diagnostic. To provide a definitive diagnosis and to achieve the control of symptoms the patient was candidated to an elective laparoscopic resection of the tumor.

Fig. 1.

CT scan shows a large mass in the pelvis in close relationship with bladder, right internal iliac vessels, sigmoid colon, ileal loops and first sacral vertebral body.

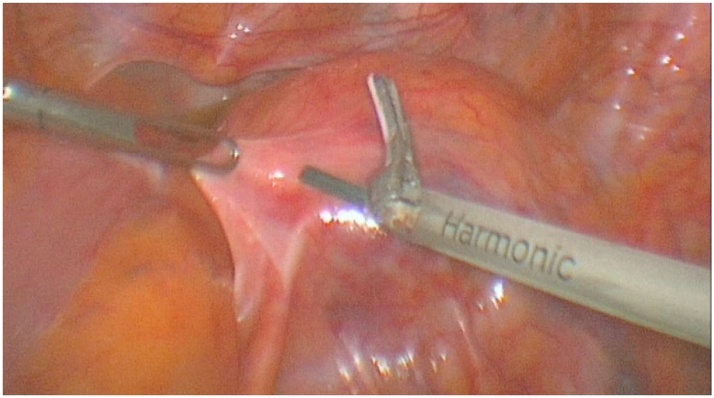

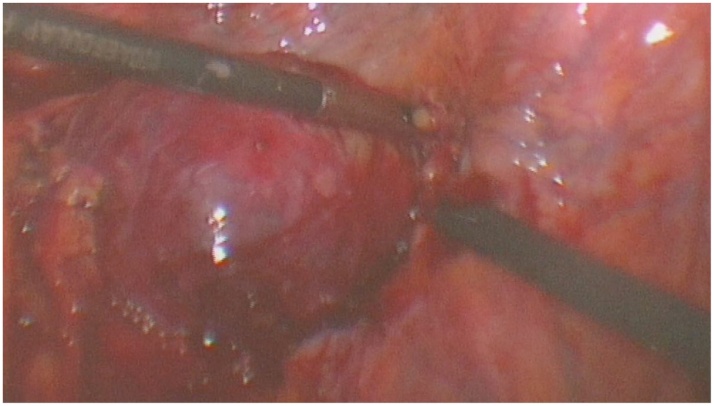

Surgical procedure was performed in general anesthesia using a 3-port configuration (umbilicus for the optical system and two 10 mm operative ports on either side 10 cm laterally) with the patient placed in supine anti-Trendelemburg position. The pelvic exploration confirmed the presence of a retroperitoneal mass located between the rectum, the bladder and the right common iliac vessels (Fig. 2). The peritoneum between the mass and the rectum was widely incised. With the aid of high flow pneumoperitoneum a cleavage plan between the tumour capsule and surrounding structures was found. The dissection, using both sharp and blunt maneuvers, extended posteriorly and laterally both from the ureter and the right iliac vessels, paying attention to preserve the integrity of the capsule and ensuring meticulous hemostasis at all time by means of the harmonic scalpel (Fig. 3). This dissection revealed the tumor origin from the pelvic hypogastric plexus. Using a gentle blunt dissection all nervous structures were macroscopically preserved. Finally, the mass was also separated medially from the rectum and then was extracted “en bloc” using an Endo-bag ® through the umbilical port site. A drain was put into the Douglas’ space.

Fig. 2.

Laparoscopic exploration revealed a subperitoneal mass sited between the rectum, the bladder and the right common iliac vessels.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative shooting: dissection of the tumour from the capsule using blunt maneuvers.

Total operative time was 148 min with an estimated blood loss of 150 mL. Post-operative progress was uneventful. The patency of the intestinal tract was obtained in 1 p.o. day. The drain was removed in 2 p.o. day. The patient was discharged in 3 p.o. day.

Surgical specimen consisted of a roundish, encapsulated mass, measuring 5 cm in largest diameter, with an external grey and yellow surface.

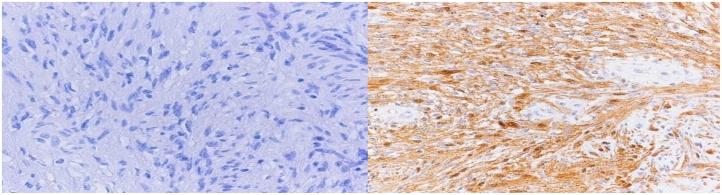

Histologically the lesion was a spindle cell neoplasm with nuclear palisading and focal cystic spaces, without mitotic activity and with strong S-100 protein immunostaining positivity (Fig. 4). Smooth muscle actin, desmin, calponin, caldesmon, CD117, DOG-1, HMB-45, and AE1/AE3 cytokeratins immunostaining was negative. These findings are coherent with the histological diagnosis of shwannoma.

Fig. 4.

Left: solid sheets of spindle cells with occasional palisading; mitotic activity is absent (100×, HH staining). Right: strong and uniform positivity for S100 protein with both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (100×, Immunostaining).

In absence of literature guidelines, a CT scan after one and two years excluded a recurrence. Two years after surgery the patient didn’t refer neurological symptoms with complete resolution of urinary symptoms.

3. Discussion

Pelvic schwannomas are rare and often asymptomatic neoplasms. If symptomatic, they may cause pain and obstructive or compressive symptoms, according to their size and location. These types of tumors are very difficult to diagnose preoperatively because neither the clinical symptoms nor the radiological characteristics are typical. Ultrasound (US), CT scans and MRI can visualize a well-defined solid mass lesion, but this modality didn’t provide definitive specific characteristics for diagnose a schwannoma [8]. Percutaneous fine-needle cytology has been proposed to achieve preoperative diagnosis. However, FNA of soft-tissue lesions in the retroperitoneum or pelvis can result technically difficult and often be unsuccessful especially for large and mixed lesions [9].

Also in our case, the tumor didn’t shown typical radiological characteristics and percutaneous CT-guided FNAB resulted non-diagnostic. In this cases, the complete surgical excision is mandatory to establish a definitive diagnosis [10].

Using PubMed database, we review the English language international literature using the MeSH terms “laparoscopic,” “minimally invasive” and “schwannoma”. We identified quite 20 previous cases of pelvic schwannomas removed by laparoscopy or robotic surgery. Retrorectal and obturatory space are the location more often involved [[5], [6], [7], [11], [12], [13]] while schwannoma of lateral pelvic space are described in only four case report [[3], [4], [14], [15]]. Here we report a case of laparoscopic extirpation of a large pelvic schwannoma arising from the hypogastric plexus in an obese man.

In all these reports some considerations clearly emerge. Laparoscopy yields to a better exposure of the operative field in a narrow working space like the pelvis with a maximized advantage in obese patients. With the improved vision of all anatomical details the risk of inadvertent vascular and nerve plexus injury is minimized. However, due to the neurological nature of the tumor, even if the laparoscopy improves the vision of details difficult to achieve by open approach, it does not prevent all the neurologic complication. The nerve fibers were part of the tumor and a complete resection is impossible without some neurologic sacrifices. It is important to stress out that if the dissection is conducted with a meticulous blunt dissection the neurological damage is minimized enough to be clinically unrelevant.

Nedelcu et coll. in a series of six retrorectal neurologic tumor removed laparoscopically reported neurologic complication in 4 cases [11]. Despite this relative high rate of neurologic complications, the Authors believe that the laparoscopic approach brings a real benefit for the dissection of this difficult region. From this perspective, a more detailed surgical technique, such as robotic surgery, should be even more useful to reduce neurological disorders following the resection of neurogenic tumors [13]. Furthermore, the patients presenting with this disease are often young and the classical advantages of this approach (fast recovery, good cosmetic outcomes) may represent an additional benefit of this approach.

In our report, the tumor was well-circumscribed and after the incision of the peritoneum the dissection of the retroperitoneal pelvic space was helped by the high pressure created by the pneumoperitoneum. The dissection, using both sharp and blunt maneuvers, was meticulously carried out in order to preserve the integrity of the capsule and ensuring a perfect hemostasis at all time of procedure using the harmonic scalpel. During the gentle dissection surrounding the vascular structures, the ureters and principal nervous structures were isolated and macroscopically preserved so that no neurological deficit was recorded. A singular vascular pedicles was easily identified and sectioned minimizing the blood loss. The lesion was entirely removed preserving the integrity of the capsule. It is essential to stress this technical aspect because, in our opinion, it is the most helpful in the prevention of local recurrence that has been reported with an incidence range from 16 to 54% in case of incomplete intra-lesional resection [3]. In our case, a clinical and radiological 24-months follow-up hasn’t shown up yet any recurrence of this pelvic tumour.

Due to the small number of cases involving laparoscopically resected schwannomas, no clear data on contraindications of laparoscopy have been reported. In our opinion, the main limitation to laparoscopic approach for pelvic schwannomas is the preoperative suspect of a malignant schwannoma. We believe that if there is a suspicion of malignancy (such as retroperitoneal sarcoma) open approach is safer and oncologically more correct. At the same time, if there is a risk of tumor rupture during laparoscopy it is mandatory the conversion to laparotomy to avoid tumor cells dissemination and partial or intralesional removing. Partial contraindications to laparoscopy should be the large tumor size and previous surgery. In our case, the relatively small size of the tumor, its radiological appearances (well-circumscribed mass with smooth, regular margins and central cystic degeneration that displace rather than invade local surrounding structures with no regional lymphoadenopaty) and the overweight of the patient with no previous abdominal surgery oriented us for the laparoscopic approach.

4. Conclusion

Despite its not yet proven, we believe, according to literature, that when pre-operative radiological studies suggest a retroperitoneal pelvic benign tumor laparoscopy may offers several advantages. The direct high-definition vision obtained by advanced laparoscopic cameras deeply into this narrow anatomical space, especially in obese patients, provides a detailed view that makes easier to isolate and spear the anatomical structures that surround the tumor. Furthermore, the pressure created by the pneumoperitoneum may help to create the right plane of dissection minimizing the risk of tumor rupture and bleeding.

Conflict of interests

There are no conflict of interests.

Sources of funding

There are no sources of funding.

Ethical approval

Not necessary for this case report as it is exempt by our institution.

Consent

Patient expressed a written informed consent to accept the publication of this paper.

Author contribution

Guadagni S. contributed by conceptualization and revision of the manuscript

Di Furia M. and Della Penna A. contributed the original idea and steasure of the manuscript.

Clementi M. contributed by conceptualization and performing the surgical procedures.

Salvatorelli A., Vicentini V. and Sista F. contributed by collecting all the data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

Prof. Marco Clementi.

References

- 1.Borghese M., et al. Benign schwannoma of the pelvic retroperitoneum: report of a case and review of the literature. G. Chir. 2000;21:232–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melvin W.S. Laparoscopic resection of a pelvic schwannoma. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. 1996;6:489–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okuyama T., et al. Laparoscopic resection of a retroperitoneal pelvic schwannoma. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014;(1) doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjt122. (pii: rjt122) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hidaka E., et al. Laparoscopic extirpation of a schwannoma in the lateral pelvic space. Case Rep. Surg. 2016;2016:1351282. doi: 10.1155/2016/1351282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marinello F.G., et al. Laparoscopic approach to retrorectal tumors: review of the literature and report of 4 cases. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2011;21(February (1)):10–13. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182020e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou J.L., et al. A laparoscopic approach to benign retrorectal tumors. Tech. Coloproctol. 2014;18(September (9)):825–833. doi: 10.1007/s10151-014-1146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duclos J., et al. Laparoscopic resection of retrorectal tumors: a feasibility study in 12 consecutive patients. Surg. Endosc. 2014;28(April (4)):1223–1229. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayasaka K., et al. MR findings in primaryretroperitoneal schwannoma. Acta Radiol. 1999;40:78–82. doi: 10.1080/02841859909174408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennert K.W., Abdul-Karim F.W. Fine needle aspiration cytology vs. needle core biopsy of soft tissue tumours. A comparison. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:381–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daneshmand S., et al. Benign retroperitoneal schwannoma: a case series and review of the literature. Urology. 2003;62:993–997. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00792-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nedelcu M., et al. Laparoscopic approach for retrorectal tumors. Surg. Endosc. 2013;27(November (11)):4177–4183. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ningshu L., et al. Laparoscopic management of obturator nerve schwannomas: experiences with 6 cases and review of the literature. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2012;22(April (3)):143–147. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182478870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deboudt C., et al. Pelvic schwannoma: robotic laparoscopic resection. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(March (1 Suppl Operative)):2–5. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31826e2d00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jindal T., et al. Cystic schwannoma of the pelvis. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2013;95(January (1)):e1–e2. doi: 10.1308/003588413X13511609956697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chopra S., et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic resection of a pelvic schwannoma. Urol. Case Rep. 2017;11(February (3)):63–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]