Abstract

We report on the incidence, risk factors, and outcome of late Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) in a cohort of 709 adult and pediatric patients at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center between September 1999 and December 2006. The SAB cases were identified by prospective surveillance and examination of a computerized database. Late SAB was defined as SAB occurring > 50 days post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). A nested case-controlled study was conducted to identify predictors of late SAB. The incidence of late SAB was 6/100,000 patient-days. The median time from stem cell infusion to incident blood culture was 137 days (range, 55 to 581 days). Eighty-four percent of the cases were community acquired; 40% involved a focal infection. Bacteremia was persistent (>3 days) despite removal of endovascular access in > 50% of cases. Risk factors for late SAB were acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) flare, acute or chronic skin GVHD (cGVHD), corticosteroid use, liver dysfunction, and prolonged hospital length of stay (LOS) post-HSCT. In multivariate models, skin GVHD (P =.002) and LOS (P =.02) remained significant. The median survival post-SAB was 135 days (range, 1 to 1765 days). Late SAB occurred mainly in the setting of GVHD or corticosteroid therapy. Clinical manifestations were highly variable. Multiple comorbidities, indicated by organ dysfunction and hospitalization, likely contributed to persistence and increased morbidity and mortality. We recommend a high index of suspicion and empiric antistaphylococcal treatment pending culture results in high-risk patients undergoing HSCT.

Keywords: Late Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia, Case-controlled, Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Mortality, Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Bacteremia is the most common infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), with a reported incidence of up to 40% [1]. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) has been associated with considerable morbidity and mortality in various clinical settings [2,3]. Despite a predominance of gram-positive organisms, S aureus is a rather rare cause of bacteremia in HSCT, with a reported incidence of 1% to 3% [4]. Importantly, the reported mortality attributed to S aureus is quite low compared with rates in non-HSCT patients [5]. The present study was conducted to investigate the incidence, risk factors, and outcome of postengraftment SAB.

METHODS

Study Patients

The study was approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Institutional Review Board. The cohort comprised 709 consecutive adult and pediatric patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT at MSKCC between September 1, 1999 and December 31, 2006. Patients were censored at relapse or second HSCT. Cases of late SAB were identified by examining a computerized microbiology database and prospectively collected epidemiology records. Clinical data were extracted from medical records.

Definitions

Late SAB was defined as at least 1 set of blood cultures positive for S aureus with clinical signs of infection occurring > 50 days after HSCT. All cultures were processed by the MSKCC Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Follow-up blood cultures were obtained routinely in patients with positive cultures. SAB was considered nosocomial if the incident blood culture was drawn > 72 hours after admission. SAB was considered sustained if blood cultures were positive for ≥ 3 days within 1 week of the incident blood culture. The recurrence interval was 7 days. Septic shock was defined as a systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg, with evidence of peripheral hypoperfusion. Pneumonia was defined as new infiltrates detected on chest radiograph and a positive bronchoalveolar lavage or endotracheal aspirate culture for S aureus. Endocarditis was defined by Duke’s criteria [6]. A central venous catheter (CVC) was considered the source of infection if bacteremia resolved promptly after catheter removal and if no other focus of infection was identified. Pocket and tunnel infections associated with intravascular devices were defined according to standard criteria [7]. Case fatality was defined as death occurring within 7 days of the incident blood culture.

Time to myeloid engraftment was calculated as the number of days from stem cell infusion to an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 1000/mm3 on 2 consecutive days after stem cell infusion. Secondary neutropenia was defined as ANC ≤ 1000/mm3 on ≥ 2 consecutive measurements after having achieved neutrophil recovery and within 30 days of SAB. Liver or kidney dysfunction was defined as a ≥ 2 consecutive measurements of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), or bilirubin > 3 times the upper limit of normal and creatinine > 2 times the upper limit of normal, respectively, between day +40 post-HSCT and the date of the incident blood culture. Values for CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte subsets and serum IgG levels at 6 months post-HSCT were recorded. Graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) was graded by standard criteria [8]. Corticosteroid use was defined as ≥ 1 mg/kg/day of methyl-prednisolone or equivalent for ≥ 14 days within 30 days before the incident blood culture. Use of steroid-sparing immunosuppressants was recorded if administered for ≥ 7 days within 30 days of the incident blood culture. Any antibiotic use for ≥ 7 consecutive days within 30 days of the incident blood culture was recorded. Overall hospital length of stay (LOS) was calculated as the total number of days in the hospital between day 40 post-HSCT and the date of the incident blood culture.

Conditioning regimens containing fractionated total body irradiation (TBI) included thiotepa and cyclophosphamide (Cy) or thiotepa and fludarabine (Flu). The non-TBI–containing regimens included busulfan (Bu) and Cy or Bu and melphalan (Mel). Recipients of unmodified HSCT received standard GVHD prophylaxis with methotrexate (MTX) or (CsA) cyclosporine-A. Recipients of T cell–depleted transplants did not receive any additional GVHD prophylaxis.

Standard care of HSCT recipients included fluconazole and acyclovir starting at cytoreduction. Patients also received Pneumocystis prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or pentamidine (in case of sulfa allergy) from day −7 to day −3. No routine antibacterial prophylaxis was given to the patients undergoing HSCT until December 2005. Starting on December 1, 2005, adult patients who underwent myeloablative conditioning received vancomycin prophylaxis starting at day −2 relative to stem cell infusion through day +7 post-HSCT.

Statistical Analysis

To determine risk factors for late SAB, we conducted a nested case-controlled study. Three controls for each case were then randomly selected from the same cohort and matched to cases on duration of follow-up, age (within 5 years), sex, and donor relationship. Each variable was initially analyzed in univariate models using conditional logistic regression. Significant variables were then combined into a single multivariate model. The final multivariate model was selected through best-subsets selection, using the score statistic as the selection criterion. Results were considered statistically significant if the P values from the likelihood ratio test were<.05. Survival plots were constructed using Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in survival curves were determined using log-rank test. All data analyses were done using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Incidence of Postengraftment SAB

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the cohort of 709 consecutive adult and pediatric patients who underwent HSCT. Median follow-up was 680 days (range, 66 to 2443 days). Twenty-nine of the 709 patients (4.1%) developed SAB. Twenty-six patients (3.6%) developed late SAB, a median of 137 days (range, 52 to 581 days) after HSCT. The incidence of late SAB was 6.0/100,000 patient days; 22 (84.6%) of these cases were community-acquired. The incidence of SAB was similar in adult and pediatric HSCT recipients (3.5% vs 3.8%; P = not significant).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Allogeneic HSCTat MSKCC between September 1, 1999, and December 31, 2006 (n = 709)

| Age, years, median (range) | 34.4 (0–71.3) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 411 (57.9) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 120 (16.9) |

| Acute myeloblastic leukemia | 197 (27.9) |

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | 38 (5.3) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 85 (11.9) |

| Lymphoma | 127 (17.9) |

| Other myeloproliferative disorder | 41 (5.8) |

| Nonmalignant condition | 101 (14.2) |

| Donor type, n (%) | |

| Matched sibling | 317 (44.7) |

| Mismatched related | 60 (8.5) |

| Matched unrelated | 332 (46.8) |

| T cell depletion, n (%) | 408 (57.5) |

| Conditioning, n (%) | |

| Myeloablative | |

| TBI-based | 320 (45.1) |

| Non TBI; all chemotherapy | 265 (37.4) |

| Nonmyeloablative | 124 (17.5) |

The rate of methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) in our cohort was 23%, compared to 38% in blood isolates of non-HSCT patients at MSKCC during the same period (p=not significant).

Clinical Presentation of Late SAB

The majority of patients (80.7%) presented with fever. Shock was noted at presentation in 42.3% of patients. Twelve patients (46.2%) had focal infections with S aureus. The most common manifestation was pneumonia, seen in 5 patients (19.2%). Three patients (11.5%) presented with skin manifestations without fever, including paronychia in 1 patient, superficial thrombophlebitis at an old i.v. site in 1 patient, and septic emboli in 1 patient. Four patients (15.3%) had a pocket or tunnel infection. Three patients (11.5%) had right-sided endocarditis.

Twenty-two of 29 (84.6%) patients had an indwelling CVC at presentation. The CVC was removed in 19 of these patients (86%), a median of 3 days from the date of the incident blood culture (range, 1 to 8 days). Eleven patients (57.9%) had persistent SAB despite CVC removal. Eight of 15 catheter tips sent for culture (53.3%) were positive for S aureus.

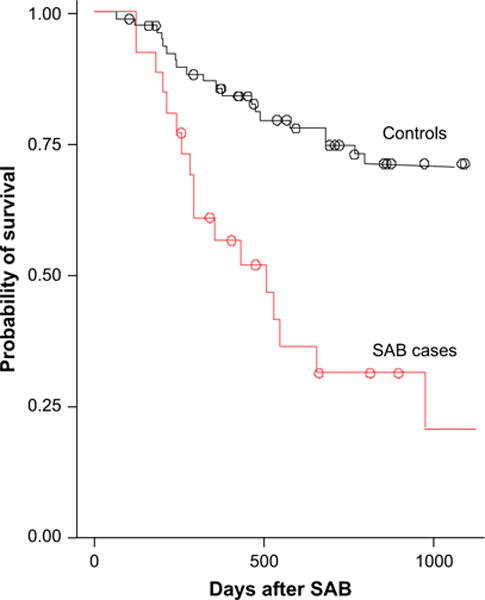

Late SAB cases had decreased overall survival compared to controls (p=0.0002) (Figure 1). Four (15.4%) patients died within 7 days (range, 1 to 7 days) of the incident blood culture.

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier probability of overall survival after diagnosis of SAB. Cases had lower survival compared to controls (p=0.0002).

Risk Factors for Late SAB

We conducted a nested case-controlled study to determine predictors for late SAB. Three controls were selected randomly from the cohort matched to cases by age, sex, donor type, and survival status. Table 2 presents the results of the univariate analysis. Risk factors for late SAB included acute GVHD (aGVHD), skin GVHD (acute or chronic), liver dysfunction, and increased hospital LOS. CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte counts, serum IgG levels, and secondary neutropenia did not differ between the SAB cases and controls. When all significant variables were entered into the multivariate models, only LOS and GVHD involving the skin remained significant (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Late SAB

| Variable | Cases (n = 26) | Controls (n = 78) | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVHD, n (%) | ||||

| Acute GVHD | 12 (46.2%) | 10 (12.8%) | 5.67 (1.95–16.49) | .0008 |

| Chronic GVHD | 7 (26.9%) | 9 (11.5%) | 3.23 (0.97–10.73) | .0571 |

| GVHD of the skin (acute or chronic) | 17 (65.4%) | 12 (15.4%) | 12.55 (3.59–43.78) | < .0001 |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 5 (19.2%) | 2 (2.6%) | 13.14 (1.51–114.10) | .0050 |

| Liver dysfunction, n (%) | ||||

| ALT >111.0 | 13 (50.0%) | 20 (25.6%) | 2.96 (1.13–7.77) | .0236 |

| AST >111.0 | 10 (38.5%) | 8 (10.3%) | 5.00 (1.68–14.88) | .0028 |

| Bilirubin >3.0 | 6 (23.1%) | 5 (6.4%) | 4.89 (1.19–20.04) | .0224 |

| Kidney dysfunction, n (%) | ||||

| Creatinine > 2.0 | 6 (23.1%) | 9 (11.5%) | 2.08 (0.71–6.06) | .1909 |

| Neutropenia | 2 (7.7%) | 5 (6.4%) | 1.22 (0.216–6.94) | .8208 |

| Immune function, median (range) | ||||

| CD4+ T cells/mL3 | 150 (0–1068) | 193 (0–992) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | .9418 |

| CD8+ T cells/mL3 | 122 (0–1570) | 144 (0–1511) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | .9497 |

| Serum IgG (mg/mL) | 606 (123–1420) | 813 (192–1915) | 0.998 (0.99–1.00) | .0460 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (range) | 27.5 (0.0–90.0) | 2.5 (0–93) | 1.042 (1.01–1.06) | < .0001 |

Table 3.

Multivariate Model of Factors Associated with Late SAB

| Variable | Cases (n = 26) | Controls (n = 78) | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital LOS, days, median (range) | 28 (0–90) | 2.5 (0–93) | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | .02 |

| Skin GVHD, n (%) | 17 (65.4%) | 12 (15.4%) | 8.87 (2.3–34.3) | .002 |

Wald statistic; the P value for the likelihood ratio test for the entire model is <.0001.

DISCUSSION

SAB has been associated with significant morbidity and mortality in various clinical settings, even when controlled for severity of illness [9]. In neutropenic patients with cancer, the incidence of SAB is 6% to 7%, with an overall mortality of 23% to 40% [12]. A large study of patients who underwent bone marrow transplantation found an SAB incidence of 3% over a 7-year period, with no attributable mortality [4]. At our institution, S aureus was a rare cause of bloodstream infection early posttransplantation (incidence < 0.5%). The heavy use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in the peri-transplantation period may be a factor in this low incidence of early SAB. In contrast, the incidence of late SAB at our institution is 3.6%, at a rate 6/ 100,000 HSCT-days.

Previous studies in HSCT recipients have reported low SAB-associated mortality in HSCT. A more recent study found high rates of septic shock and death associated with SAB in patients with hematologic malignancies (although only 9 of 34 patients had undergone HSCT and 17 of 34 had neutropenia, including the 6 who died of septic shock) [10]. In our cohort, the case fatality rate was 15%, with an attributable mortality rate of 8%. SAB was associated with substantial morbidity due to focal infections and persistent bacteremia requiring prolonged hospitalization and treatment.

We next conducted a nested case-controlled study to identify predictors for late SAB bacteremia and to help develop guidelines for managing patients at high risk for SAB. Nested case-controlled studies offer several advantages over traditional case-controlled studies; they eliminate recall bias and can establish a temporal relationship between putative risk factors and outcomes [11]. The limitations of our study are inherent to its retrospective nature and limited sample size. We cannot exclude a potential selection bias, because nondiseased persons from whom the controls were selected may not be fully representative of the original cohort. There was no routine surveillance during our study period; thus, previous colonization with S aureus is unknown. Our study is the largest study of postengraftment SAB in allogeneic HSCT reported to date. We have identified important risk factors and provided practical guidance in antibiotic selection.

aGVHD involving any organ were associated with late SAB. In particular, skin involvement by GVHD was found to be a major risk factor for late SAB. Integrity of the skin and mucus membranes constitutes the first line of defense against invading pathogens. The immune suppression and multiple comorbidities related to GVHD and its treatment likely contributed to the high rates of persistent late SAB (54.5% of cases surviving > 7 days from the first positive culture).

Corticosteroids are known to increase the susceptibility to infection. More specifically, corticosteroids are a major risk factor for invasive fungal infections in HSCT. We found a specific association between corticosteroid use and SAB. In concurrence with our findings, in a previously reported MRSA outbreak in a transplantation unit, allogeneic HSCT recipients who developed MRSA bacteremia were more likely to have GVHD, and MRSA was definitely or possibly implicated in half of the deaths occurring in these patients [12].

Liver and kidney dysfunction were associated with SAB, but failed to show a statistically significant association with late SAB in the multivariate analysis, suggesting multicollinearity between these risk factors. Markers of immune reconstitution of B cells and T cells were not associated with SAB. Interestingly, prolonged hospital LOS, likely representing a crude marker of comorbidities and posttransplantation complications, remained significant in multivariate analysis.

More than half of our patients had persistent SAB bacteremia without evidence of focal infection. Most of the cases of SAB were community-acquired. Although patients undergoing HSCT are instructed to seek prompt medical attention for infections, the lack of fever in several of our patients may have led to a delay in initiating treatment. Although the majority of patients had an indwelling CVC at the time of diagnosis, in our experience the CVC was not the initial source of SAB in most of these cases. CVC removal was required in most cases, however, due to either shock at presentation or persistent bacteremia, possibly due to secondary CVC infection. Even after removal of infected CVCs, most of our patients received prolonged (4 to 6 weeks) treatment because of persistent bacteremia and concern for possible secondary seeding to major organs.

Although relatively rare in our cohort, S aureus was the most common pathogen of bloodstream infection in patients with skin GVHD during the study period. The rate of MRSA isolates obtained from our patients was lower than our institution’s MRSA rate during the study period. Interestingly, the case fatality of MRSA bacteremia was higher than that of methicillin-susceptible S aureus bacteremia (33% vs 10%). A larger study is needed to investigate whether MRSA carries a higher mortality in HSCT compared with methicillin-sensitive isolates.

In summary, late SAB occurred mainly in patients with GVHD or those receiving corticosteroid therapy. In our immunosuppressed patients, shock, focal infections, and persistent bacteremia were common complications. Clinical presentation of SAB was highly variable; thus, we advocate a high index of suspicion in high-risk patients. We recommend initiating of empiric antistaphylococcal therapy in these high-risk patients pending culture results. Although most of our S aureus cases were community-acquired, vancomycin should be considered in the initial treatment regimen, because these patients are in close contact with the health care environment, and MRSA isolates are increasing in the community. Each institution should tailor the empiric antibiotic regimen for patients at high risk for late SAB based on rates of MRSA in both the institution and the community.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Almyroudis NG, Fuller A, Jakubowski A, et al. Pre- and post-engraftment bloodstream infection rates and associated mortality in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Transplant Infect Dis. 2005;7:11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2005.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopal AK, Fowler VG, Jr, Shah M, et al. Prospective analysis of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in nonneutropenic adults with malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1110–1115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.5.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collin BA, Leather HL, Wingard JR, et al. Evolution, incidence, and susceptibility of bacterial bloodstream isolates from 519 bone marrow transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:947–953. doi: 10.1086/322604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aksu G, Ruhi MZ, Akan H, et al. Aerobic bacterial and fungal infections in peripheral blood stem cell transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:201–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med. 1994;96:200–209. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mermel LA, Farr BM, Sherertz RJ, et al. Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1249–1272. doi: 10.1086/320001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 consensus conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, et al. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:53–59. doi: 10.1086/345476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghanem GA, Boktour M, Warneke C, et al. Catheter-related Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in cancer patients: high rate of complications with therapeutic implications. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86:54–60. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318030d344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordis L. Epidemiology. 3rd. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw BE, Boswell T, Byrne JL, et al. Clinical impact of MRSA in a stem cell transplant unit: analysis before, during and after an MRSA outbreak. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:623–629. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]