Abstract

BACKGROUND

Aortic root diameter (AoD) increases with aging and is related to body size. AoD is also presumed to increase in hypertension. In prior studies, however, after adjusting for age and body size, AoD did not differ between hypertensive and normotensive (NT) individuals. Hypertension is a heterogeneous condition with various subtypes that differ in pathophysiology and age distribution. We assessed whether AoD differs among subjects with the various subtypes of hypertension and nonhypertensive individuals.

METHODS

In 1,256 volunteers aged 30–79 years (48% women, 48% hypertensive; all untreated), AoD was measured at the sinuses of Valsalva with transthoracic echocardiography. Using cutoff values based on the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, subjects were identified as NT (23%), or prehypertensive (PH, 29%), or as having isolated diastolic (IDH, 6%), isolated systolic (ISH, 12%), or systolic–diastolic (SDH, 30%) hypertension. Groups were compared using analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s correction.

RESULTS

AoD increased with age and body surface area (BSA) in both men (r = 0.25 and 0.19, respectively) and women (r = 0.30 and 0.22, respectively) (all P < 0.0001). In men, those identified as having IDH, ISH, and SDH each had a 6% larger AoD than NT individuals (all P < 0.05). In women, those identified with ISH and SDH had a 10 and 8% larger AoD than NT individuals, respectively (all P < 0.05). In both sexes, after indexing to BSA, only ISH individuals exhibited larger AoD compared with NT individuals (both P < 0.05). But, with further adjustment for age, these differences were no longer observed.

CONCLUSIONS

Even when the subtypes of hypertension are examined separately, age and BSA, not hypertension status, account for the AoD differences between NT and hypertensive subjects.

The central aorta dilates with advancing age in both humans1 and nonhuman primates.2 The age-associated increase in aortic root diameter (AoD) is explained based on the physical principles of material fatigue and fracture, where exposure to repeated cyclic stretching results in thinning, splitting and fragmentation of the elastin fibers within the aortic media.3,4 Traditionally, chronic exposure to high intra-arterial pressures in hypertension is thought to accelerate elastin breakdown, and is therefore thought to further promote the age-associated proximal aortic dilatation.4,5 However, previous studies have found that after adjusting for age and body size, AoD did not differ between normotensive (NT) and hypertensive individuals,6–10 or was even smaller in the latter.11,12 In most of these studies,6–11 the various subtypes of hypertension, i.e., isolated systolic (ISH), isolated diastolic (IDH), and systolic–diastolic (SDH) hypertension were combined into a single group. Distinguishing among these subtypes may be important since the prevalence of each subtype varies according to age,13 and because they each result from differing underlying pathophysiologies.14

Accordingly, the aim of this analysis was to compare AoD between NT individuals and subjects with the various subtypes of hypertension while accounting for age and body size.

METHODS

Study population

The study population comprised 1,256 volunteers from Taiwan, aged 30–79 years (48% women, 48% hypertensive), none of whom were on antihypertensive medications. All participants underwent a cardiovascular evaluation; which included taking a complete medical history and conducting a physical examination, and a transthoracic echocardiography as previously described.15 All participants were free from diabetes mellitus, angina pectoris, and peripheral vascular disease, and showed no clinical or echocardiographic evidence of other significant cardiovascular disease. Specifically, the study subjects were free from congenital heart disease (including bicuspid aortic valve) and from significant valvular abnormalities (including valvular regurgitation, stenosis, or calcification that was more than mild in severity). All participants gave informed consent and the study was approved by the institutional review boards.

Definition of blood pressure groups

Hypertension was defined as a value of systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg. Using the cutoff values given by the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure,16 the study population was stratified into five blood pressure (BP) groups:

NT: SBP <120 mm Hg and DBP <80 mm Hg (N = 288)

Prehypertensive (PH): 120 ≤ SBP < 140 mm Hg and DBP <90 mm Hg, or SBP <140 mm Hg and 80 ≤ DBP < 90 mm Hg (N = 364)

IDH: SBP <140 mm Hg and DBP ≥90 mm Hg (N = 79)

ISH: SBP ≥140 mm Hg and DBP <90 mm Hg (N = 154)

SDH: SBP ≥140 mm Hg and DBP ≥90 mm Hg (N = 371).

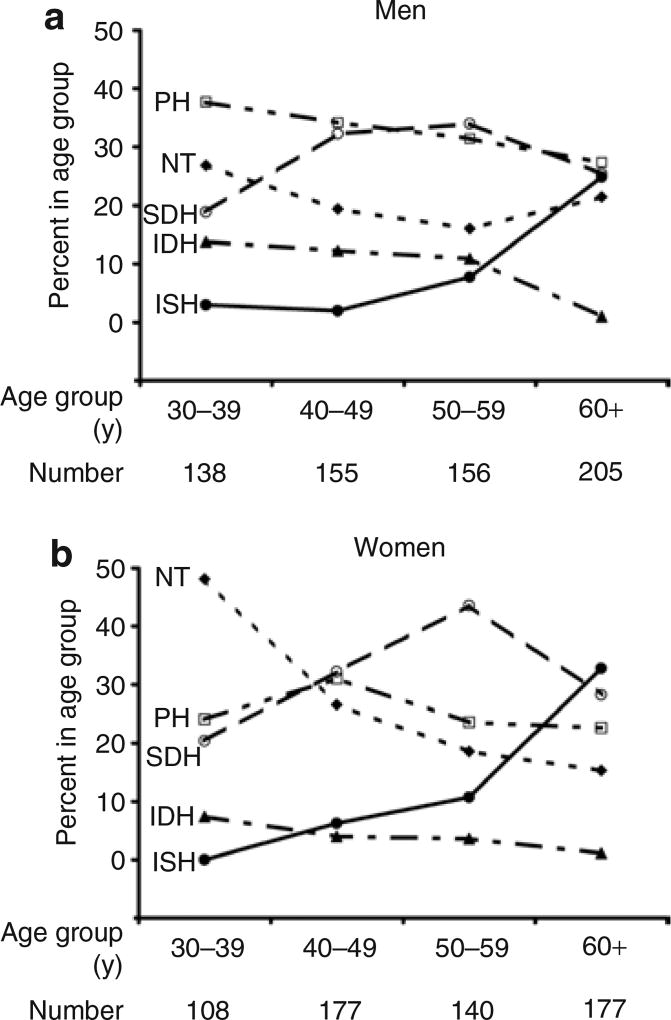

Figure 1 shows the proportion of the study cohort within each BP group according to age, in men and women.

Figure 1.

Proportion of (a) men and (b) women in the blood pressure groups according to age group. Note how the prevalence of the various subtypes of hypertension changes with age; with advancing age, IDH becomes less prevalent, whereas ISH becomes progressively more prevalent in both men and women. IDH, isolated diastolic hypertension; ISH, isolated systolic hypertension; NT, normotensive; PH, prehypertensive; SDH, systolic–diastolic hypertension.

Definition of variables

Anthropometric and BP variables

Body surface area (BSA) was estimated from measured height and weight using the formula (BSA (m2) = 0.007184 × height (cm)0.725 × weight (kg)0.425) and body mass index was calculated as (body mass index (kg/m2) = weight (kg)/height (m)2). Brachial SBP and DBP were measured in the sitting position with conventional sphygmomanometry using an appropriately sized cuff. Reported BPs represent the average of at least two consecutive measurements. Brachial pulse pressure was calculated as (SBP − DBP), and mean arterial pressure was calculated as (DBP + (pulse pressure/3)).

AoD

All subjects underwent transthoracic echocardiography by the same experienced sonographer using a Hewlett-Packard Sonos 500U system (Hewlett-Packard, Andover, MA) equipped with a 2.5 MHz transducer. AoD was measured at end-diastole at the level of the sinuses of Valsalva using 2D guided M-mode echocardiograms as previously described.15 AoD measurements were made in triplicates and the average was used in the analyses. Consistent with previous studies,17,18 preliminary analyses in our cohort showed that age and BSA were the most important determinants of AoD, and that after adjusting for age, AoD correlated more strongly with BSA (partial correlation coefficient (r′) = 0.45) than with height (r′ = 0.39), weight (r′ = 0.41), or body mass index (r′ = 0.20) (P < 0.001 for all correlations). Therefore, to account for individual differences in body size, aortic diameter index (AoDi) was calculated by indexing AoD to BSA (AoDi = AoD/BSA).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed separately for men and women with SPSS 14.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Correlations between variables were assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Group profiles were compared with Student’s t-test, or with analysis of variance followed by the application of Bonferroni’s multiple comparison method at a significance level of 0.05. Adjusted comparisons were performed by including the variable of interest as a covariate, in the analysis of variance models. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. unless otherwise specified. Statistical significance was inferred for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Anthropometric and hemodynamic profiles of the BP groups

Table 1 summarizes the anthropometric and hemodynamic profiles of men and women in the different BP groups. In both men and women, on average, the ISH group presented with the highest age among all BP groups and the IDH group had the lowest age among the hypertensive groups. In both sexes, BSA in the NT group was lower than in the PH, IDH, and SDH groups; and BSA in the ISH group was lower than in the other two hypertensive groups.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and hemodynamic profiles of men and women in the study groups

| BP Group | NT | PH | IDH | ISH | SDH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||

| N | 136 | 210 | 57 | 70 | 181 |

| Age (years) | 50 ± 13 | 51 ± 13a | 45 ± 8 | 64 ± 11a,b,c | 53 ± 11a,d |

| BSA (m2) | 1.66 ± 0.14 | 1.73 ± 0.14b | 1.81 ± 0.15b,c,d | 1.70 ± 0.14 | 1.76 ± 0.15b,d |

| HR (min−1) | 72 ± 10 | 74 ± 10 | 74 ± 10 | 72 ± 11 | 75 ± 11 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 109 ± 7 | 125 ± 7b | 134 ± 4b,c | 151 ± 12a,b,c | 160 ± 16a,b,c,d |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 69 ± 6 | 80 ± 6b | 95 ± 5b,c,d | 82 ± 6b | 101 ± 9a,b,c,d |

| PP (mm Hg) | 39 ± 6 | 45 ± 9a,b | 38 ± 6 | 69 ± 13a,b,c | 59 ± 14a,b,c,d |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 83 ± 6 | 95 ± 5b | 108 ± 4b,c | 105 ± 6b,c | 121 ± 10a,b,c,d |

| Women | |||||

| N | 152 | 154 | 22 | 84 | 190 |

| Age (years) | 47 ± 13 | 51 ± 12b | 45 ± 9 | 64 ± 10a,b,c | 53 ± 11a,b,d |

| BSA (m2) | 1.51 ± 0.12 | 1.55 ± 0.12b | 1.63 ± 0.12b,d | 1.54 ± 0.14 | 1.61 ± 0.13b,c,d |

| HR (min−1) | 72 ± 9 | 74 ± 10 | 73 ± 9 | 72 ± 9 | 75 ± 10b |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 108 ± 7 | 126 ± 7b | 132 ± 6b | 156 ± 13a,b,c | 166 ± 19a,b,c,d |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 69 ± 6 | 79 ± 6b | 93 ± 3b,c,d | 81 ± 6b | 100 ± 9a,b,c,d |

| PP (mm Hg) | 38 ± 7 | 47 ± 9b | 40 ± 5 | 74 ± 15a,b,c | 66 ± 17a,b,c,d |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 82 ± 6 | 95 ± 5b | 106 ± 3b,c | 106 ± 6b,c | 122 ± 11a,b,c,d |

BP, blood pressure; BSA, body surface area; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; IDH, isolated diastolic hypertension; ISH, isolated systolic hypertension; MAP, mean arterial pressure; NT, normotensive; PH, prehypertensive; PP, pulse pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SDH, systolic–diastolic hypertension.

Significant vs. IDH;

significant vs. NT;

significant vs. PH;

significant vs. ISH.; all based on Bonferroni’s multiple comparison method with significance level of 0.05.

In both men and women, SBP gradually increased from the lowest values in the NT group to progressively higher values in the PH, IDH, and ISH groups, to the highest values in the SDH group. In both sexes, DBP and mean arterial pressure were lowest in the NT group and highest in the SDH group, and pulse pressure was highest in the ISH group.

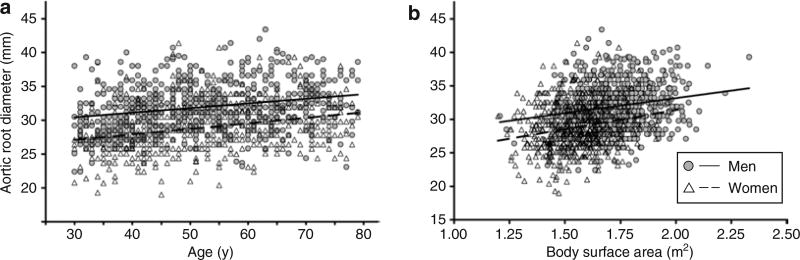

The relationship of AoD with age and BSA

When the entire cohort was considered, on average, AoD measured 31.9 ± 3.5 mm in men and 28.9 ± 3.5 mm in women. As illustrated in Figure 2a, AoD increased with advancing age at an overall average rate of 2% per decade in men (r = 0.25, P < 0.0001) and 3% per decade in women (r = 0.30, P < 0.0001). Similarly, AoD increased with increasing BSA in both men (r = 0.19, P < 0.0001) and women (r = 0.22, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2b). As shown in Table 2, there were significant correlations between AoD and all indices of BP in both the sexes.

Figure 2.

The relationship of aortic root diameter with age (a) and (b) body surface area in men (circles) and women (triangles). As indicated by the linear regression lines for men (solid lines) and women (dashed lines), aortic root diameter increased with age and body size in both sexes.

Table 2.

Correlates of the aortic root diameter in the study cohort

| Variable | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.25* | 0.30* |

| BSA | 0.19* | 0.22* |

| HR | 0.14† | −0.03 |

| PP | 0.09‡ | 0.20* |

| MAP | 0.21* | 0.27* |

| SBP | 0.19* | 0.26* |

| DBP | 0.21* | 0.24* |

Values represent Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

BSA, body surface area; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PP, pulse pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

P < 0.0001;

P < 0.001;

P < 0.05.

Comparisons of AoD

Comparisons between hypertensive and nonhypertensive subjects

Hypertensive subjects (from IDH, ISH, and SDH groups combined) had larger AoD values than nonhypertensive individuals (from NT and PH groups combined) in both men (32.7 ± 3.4 mm vs. 31.2 ± 3.4 mm, respectively, P < 0.0001) and women (29.7 ± 3.4 mm vs. 28.0 ± 3.3 mm, respectively, P < 0.0001). When the comparisons were adjusted for age alone, these results were not altered. When AoD was indexed to BSA, hypertensive men tended to have larger AoDi values than nonhypertensive men (18.8 ± 2.4 mm/m2 vs. 18.4 ± 2.4 mm/m2, respectively, P = 0.058), and hypertensive women had larger AoDi values than nonhypertensive women (18.9 ± 2.6 mm/m2 vs. 18.4 ± 2.4 mm/m2, respectively, P = 0.02). But, when AoDi was further adjusted for age, these differences were no longer present in either sex.

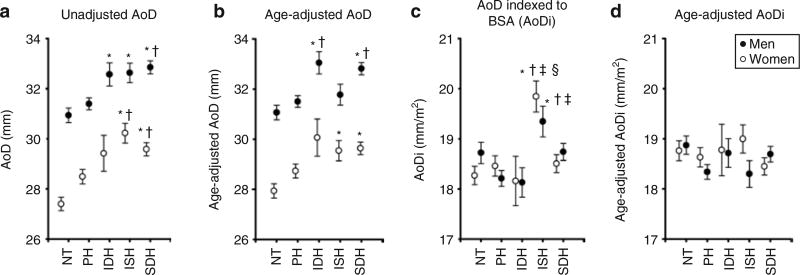

Comparisons among the five BP groups

When subjects were stratified according to the five BP groups, in men, AoD in the three hypertensive groups (IDH, ISH, and SDH) was 6% larger than in the NT group, and AoD in the SDH group was 5% larger than in the PH group (all P < 0.05). In women, AoD in the ISH group was 10% larger than in the NT group and 6% larger than that in the PH group, and AoD in the SDH group was 8% larger than in the NT group and 4% larger than in the PH group (all P < 0.05). Thus, subjects from all hypertensive groups in men and from groups with systolic hypertension in women had larger AoD values than those in the NT group (Figure 3a). The effects of adjusting for age while comparing AoD values among the different BP groups are illustrated in Figure 3b. In men, after adjusting for age, AoD in the SDH group remained larger than in the NT and PH groups, and AoD in the IDH group was now larger than in both NT and PH groups. However, age-adjusted AoD in the ISH group was no longer larger than in the NT group in men. In women, age-adjusted AoD in ISH and SDH groups remained larger than in the NT group, but were no longer larger than in the PH group. In both men and women, when AoD was indexed to BSA, ISH was the only hypertensive group that exhibited a higher AoDi than that of the NT group (Figure 3c). Importantly, these differences were no longer significant when AoDi was further adjusted for age (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Effects of age and body surface area (BSA) on the comparisons of aortic root diameter (AoD) among blood pressure groups in men (solid circles) and women (open circles). Note how the differences among blood pressure groups in (a) unadjusted comparisons of AoD are modified when (b) AoD is adjusted for age or (c) indexed to BSA, and are no longer significant when (d) aortic diameter index (AoDi) is adjusted for age. Comparisons among blood pressure groups were performed separately for men and women using analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison method with a significance level of 0.05. *Significant compared to normotensive (NT); †significant compared to prehypertensive (PH); ‡significant compared to isolated diastolic hypertension (IDH); §significant compared to systolic–diastolic hypertension (SDH). Values shown in b and d are estimated marginal means corresponding to the mean age for men and women in the cohort (52 years for both). Error bars represent s.e.m.

These results were not altered when we repeated the comparisons of AoD among the five BP groups for both men and women while adjusting for (i) age and body mass index, or (ii) age, height, and weight.

DISCUSSION

In this study, which was conducted in a large cohort of individuals with a broad age range, AoD was compared among NT, PH, and untreated hypertensive subjects who were further stratified into the various subtypes of hypertension. We found that individuals from all hypertensive groups in men and those with systolic hypertension in women had larger AoD values than their NT counterparts. However, after accounting for age and BSA, there were no significant differences in AoD among the five BP groups.

Previous comparisons of AoDs between hypertensive and NT subjects

Traditional views hold that hypertension leads to proximal aortic dilatation by accelerating the age-associated fracture of elastin fibers in the aortic media.4,5 However, data from previous studies, which assessed either end-diastolic or end-systolic AoD using various methodologies,6–11 do not corroborate this view. Dunn et al. compared end-systolic AoD (indexed to BSA) between hypertensive (n = 31) and control (n = 14) subjects and, even without adjusting for age, found no differences between the two groups, likely reflecting the relatively narrow age range of the subjects (22–50 years) in their study.6 Similarly, Savage et al. compared AoD between hypertensive (n = 234) and NT (n = 134) subjects in a cohort with a broader age range (19–70 years) and found that after accounting for age and BSA, AoD did not differ among the BP groups.7 In a large autopsy series that included both Caucasian and Chinese subjects, Virmani et al. also found that after adjusting for age, height, and weight, aortic root circumference did not differ between NT and hypertensive subjects.9 Kim et al. compared AoD at four different levels (annulus, sinuses of Valsalva, supra-aortic ridge, and ascending aorta) between sex- and age-matched NT and hypertensive subjects (n = 110 each), and found that after indexing AoD to BSA, the groups had similar AoD at all measured levels.10 In another study, Palmieri et al. found that after adjusting for age and BSA, hypertensive subjects (n = 2,096) had significantly smaller AoD compared to the NT individuals (n = 361).11 In that study,11 a subgroup analysis showed that hypertensive subjects with suboptimal BP control (defined as DBP ≥90 mm Hg), on average, had larger AoD compared to NT controls, whereas optimally treated hypertensive subjects had smaller AoD compared to NT controls.

It is important to note that hypertension is a heterogeneous condition composed of subtypes with differing underlying pathophysiologies: ISH and IDH are considered to result from a predominant rise in central arterial stiffness and peripheral vascular resistance, respectively, whereas SDH is thought to arise from a concomitant increase in both central arterial stiffness and peripheral vascular resistance.14 Moreover, with increasing age, ISH becomes more prevalent, whereas the prevalence of IDH decreases.13 Therefore, we sought to assess whether blending of the various subtypes of hypertension into a single group in the previous studies6–11 could explain the discrepancy between the traditional viewpoint and the results of the aforementioned studies.

AoD in the subtypes of hypertension

In a substudy of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program, Pearson et al. did not find any differences in AoD between NT individuals (n = 55) and those with ISH (n =104), all of whom were 60 years of age or older.8 But, contrary to the traditional view, in a study of middle-aged and older individuals, Mitchell et al. found that subjects with systolic hypertension had a smaller “effective” aortic diameter than NT controls.12 However, that study was criticized for relying on calculated, rather than measured, aortic diameter.19 In the present study, we compared directly measured AoD among subjects grouped under the various subtypes of hypertension and nonhypertensive individuals. We also subdivided the nonhypertensive group into NT and PH because they have been shown to possess differing cardiovascular and hemodynamic characteristics.20 We first replicated the results of the previous studies6–10 by showing that, even though hypertensive subjects (from IDH, ISH, and SDH groups combined) had larger unadjusted AoD than nonhypertensive individuals (from NT and PH groups combined), after accounting for BSA and age, AoDi did not differ between the two groups. Next, we found that, in unadjusted comparisons, each hypertensive group in men and those with systolic hypertension in women had larger AoD than their NT counterparts. Adjusting AoD for age alone mostly affected the comparisons of AoD among nonhypertensive groups vs. the ISH group (Figure 3b), which had the highest age among all BP groups. By contrast, indexing AoD to BSA mostly affected the comparisons of AoD among the nonhypertensive groups vs. the groups with diastolic hypertension (IDH and SDH, Figure 3c), which had higher BSA values than ISH and NT groups. Clearly, these results reflect the differences in age and BSA among the various subtypes of hypertension (Table 1). However, differences in AoD among the five BP groups were no longer present when age and BSA were both taken into account.

Thus, our study extends the findings of the previous studies by showing, for the first time, that, after accounting for age and BSA, AoD does not differ between NT and hypertensive individuals, even when the various subtypes of hypertension are examined separately.

The results of our study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. Aortic root measurements were only performed at a single level. However, Kim et al. found that, after indexing aortic diameters to BSA, the level of the aorta at which the diameter was measured did not affect the comparisons of aortic diameters between NT and hypertensive subjects.10 In addition, the study cohort was drawn from a population in Taiwan, with epidemiologic features, and dietary and exercise habits that may be different than Caucasian populations. Nevertheless, our results are comparable to those obtained in studies which included mostly Caucasian populations.6–10 Therefore, our findings are unlikely to be related to differences in study population or measurement techniques. However, given the inherent limitations of a cross-sectional study, our findings require confirmation in longitudinal studies.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that, even when the various subtypes of hypertension are considered separately, age and body size, rather than BP status, account for the apparent differences in AoD between NT and hypertensive individuals. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these results.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, and National Institutes of Health Research and Development Contract NO1-AG-1-2118. The authors thank the participants and the medical staff in the Pu-Li, Kuo-Hsin, and Kin-Chen health stations for their support of manpower and space for this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139–146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048892.83521.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakatta EG. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part III: cellular and molecular clues to heart and arterial aging. Circulation. 2003;107:490–497. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048894.99865.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakatta EG, Mitchell JH, Pomerance A, Rowe GG. Human aging: changes in structure and function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10(2 Suppl A):42A–47A. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols WW, O’Rourke MF. McDonald’s Blood Flow in Arteries. 5. Arnold: London, UK; 2005. pp. 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Rourke MF, Nichols WW. Aortic diameter, aortic stiffness, and wave reflection increase with age and isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:652–658. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153793.84859.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn FG, Chandraratna P, deCarvalho JG, Basta LL, Frohlich ED. Pathophysiologic assessment of hypertensive heart disease with echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1977;39:789–795. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(77)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savage DD, Drayer JI, Henry WL, Mathews EC, Jr, Ware JH, Gardin JM, Cohen ER, Epstein SE, Laragh JH. Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac anatomy and function in hypertensive subjects. Circulation. 1979;59:623–632. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.59.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson AC, Gudipati C, Nagelhout D, Sear J, Cohen JD, Labovitz AJ. Echocardiographic evaluation of cardiac structure and function in elderly subjects with isolated systolic hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:422–430. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virmani R, Avolio AP, Mergner WJ, Robinowitz M, Herderick EE, Cornhill JF, Guo SY, Liu TH, Ou DY, O’Rourke M. Effect of aging on aortic morphology in populations with high and low prevalence of hypertension and atherosclerosis. Comparison between occidental and Chinese communities. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:1119–1129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim M, Roman MJ, Cavallini MC, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG, Devereux RB. Effect of hypertension on aortic root size and prevalence of aortic regurgitation. Hypertension. 1996;28:47–52. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmieri V, Bella JN, Arnett DK, Roman MJ, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Paranicas M, Rao DC, Devereux RB. Aortic root dilatation at sinuses of valsalva and aortic regurgitation in hypertensive and normotensive subjects: the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network Study. Hypertension. 2001;37:1229–1235. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell GF, Lacourciere Y, Ouellet JP, Izzo JL, Jr, Neutel J, Kerwin LJ, Block AJ, Pfeffer MA. Determinants of elevated pulse pressure in middle-aged and older subjects with uncomplicated systolic hypertension: the role of proximal aortic diameter and the aortic pressure-flow relationship. Circulation. 2003;108:1592–1598. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093435.04334.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin SS, Jacobs MJ, Wong ND, L’Italien GJ, Lapuerta P. Predominance of isolated systolic hypertension among middle-aged and elderly US hypertensives: analysis based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Hypertension. 2001;37:869–874. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.3.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verdecchia P, Angeli F. Natural history of hypertension subtypes. Circulation. 2005;111:1094–1096. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158690.78503.5F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CH, Ting CT, Lin SJ, Hsu TL, Ho SJ, Chou P, Chang MS, O’Connor F, Spurgeon H, Lakatta E, Yin FC. Which arterial and cardiac parameters best predict left ventricular mass? Circulation. 1998;98:422–428. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.5.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kramer-Fox R, O’Loughlin J. Two-dimensional echocardiographic aortic root dimensions in normal children and adults. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:507–512. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Echocardiographic reference values for aortic root size: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1995;8:793–800. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(05)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Rourke MF, Safar ME, Nichols WW. Proximal aortic diameter and aortic pressure-flow relationship in systolic hypertension. Circulation. 2004;109:e227–e228. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128539.55559.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drukteinis JS, Roman MJ, Fabsitz RR, Lee ET, Best LG, Russell M, Devereux RB. Cardiac and systemic hemodynamic characteristics of hypertension and prehypertension in adolescents and young adults: the Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;115:221–227. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]