Abstract

Background

In the course of neurological early rehabilitation, decannulation is attempted in tracheotomized patients after weaning due to its considerable prognostic significance. We aimed to identify predictors of a successful tracheostomy decannulation.

Methods

From 09/2014 to 03/2016, 831 tracheotomized and weaned patients (65.4 ± 12.9 years, 68% male) were included consecutively in a prospective multicentric observation study. At admission, sociodemographic and clinical data (e.g. relevant neurological and internistic diseases, duration of mechanical ventilation, tracheotomy technique, and nutrition) as well as functional assessments (Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R), Early Rehabilitation Barthel Index, Bogenhausener Dysphagia Score) were collected. Complications and the success of the decannulation procedure were documented at discharge.

Results

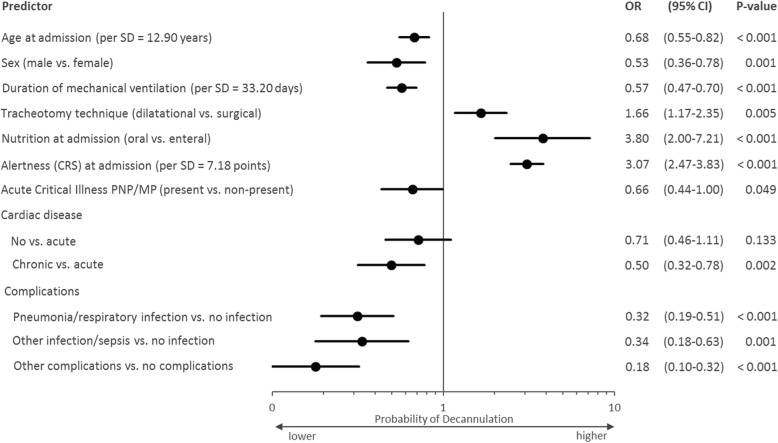

Four hundred seventy patients (57%) were decannulated. The probability of decannulation was significantly negatively associated with increasing age (OR 0.68 per SD = 12.9 years, p < 0.001), prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation (OR 0.57 per 33.2 days, p < 0.001) and complications. An oral diet (OR 3.80; p < 0.001) and a higher alertness at admission (OR 3.07 per 7.18 CRS-R points; p < 0.001) were positively associated.

Conclusions

This study identified practically measurable predictors of decannulation, which in the future can be used for a decannulation prognosis and supply optimization at admission in the neurological early rehabilitation clinic.

Keywords: Mechanical ventilation, Tracheostomy, Decannulation, Prognosis

Background

The number of tracheotomies conducted for more comfortable long-term ventilation has increased rapidly in recent years. Therefore, a growing number of patients with a tracheal cannula (TC) will be transferred from Intensive Care Units (ICU) to neurological-neurosurgery early rehabilitation clinics (ERC) to be weaned (ERC are intermediate units for the rehabilitation of severely care-dependent patients in Germany). A study on the long-term outcome of early rehabilitation patients showed that this weaning is of outstanding importance. If it fails, the probability of survival is significantly reduced after discharge from the ERC: One year later, less than 50% of the patients who were discharged with a TC survived [1]. Therefore, for a therapeutic and economical optimization of decannulation management, it is of great interest which factors make the success or failure of decannulation more likely.

In recent years, the attempt has often been made to identify suitable decannulation predictors. These include, for example, a Peak Cough Flow > 160 l/min [2], a sufficiently high Cough Peak Flow Rate in induced cough [3] or a sufficient peripheral and respiratory muscular strength [4]. A systematic review [5] showed that effective coughing and tolerance of TC occlusion ≧ 24 h were the most relevant parameters for decannulation in clinical practice. In addition, the degree of consciousness, the condition of the tracheal secretion, the swallowing capacity, the respiratory stability before and after TC occlusion (paCO2 < 60 mmHg), bronchoscopically secured tracheal stenosis, the indications for tracheotomy and the number of comorbidities (≥ 1) proved to be important predictive parameters.

A problem with these predictors is, above all, how to ascertain them. On the one hand, measurements (e.g. the Cough Peak Flow Rate) require specific measuring instruments which are not usually available in the ERC. On the other hand, many factors are difficult to quantify (e.g., a “sufficiently high” muscular strength) or can be distorted by a subjective bias (e.g., the assessment of swallowing ability or secretion). The aim of this study was therefore to identify practicable predictors for successful decannulation in the ERC.

Methods

Sample and data collection

In a prospective multicentric registry study, the medical routine data of n = 831 consecutive tracheotomized ERC patients were collected. A patient consent was not required, because only routine medical data were collected and evaluated anonymously and no interventions were performed. The routine data were documented at the participating clinics without personal data (name, place of residence, etc.). The recruiting was carried out between 09/2014 and 03/2016 at five ERCs in the Berlin/Brandenburg area. Inclusion criteria were a tracheotomy due to invasive mechanical long-term ventilation and a successful weaning from mechanical ventilation in the ICU or ERC.

We collected sociodemographic data (age, sex), medical data (type of critical illness, neurological, cardiac, pulmonary, renal, gastrointestinal, oncological, orthopedic and psychiatric comorbidities, respiratory parameters, tracheotomy technique), functional assessments (Early Rehabilitation Barthel Index, Bogenhausener Dysphagia Score, Coma Recovery Scale-Revised), and complications during the decannulation and rehabilitation periods (pneumonia, sepsis, laryngeal edema, tracheal stenosis, tracheomalacia). The primary endpoint was the decannulation status at discharge from the ERC (decannulated vs. nondecannulated). A decannulation was being assessed as successful if no respiratory complications occurred during the patient‘s stay in the ERC (or at least 2 weeks after decannulation). A standardized procedure for tracheal cannula management [6] was not available for all five participating clinics.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are represented as mean ± standard deviation, categorial variables as absolute values and percentages. Group differences were determined by t-test or Chi²-test. The primary endpoint was analyzed using a binary logistic regression model with stepwise backwards elimination. The following covariates were taken into account: age at admission, sex, CRS-R at admission, number of complications, duration of mechanical ventilation, chronic neurological disease, acute cerebral infarction, acute nontraumatic hemorrhage, acute traumatic brain injury, acute hypoxic brain damage, Morbus Parkinson, acute critical illness polyneuro−/myopathy (CIP/CIM), acute epilepsy, cardiac disease (no vs. acute vs. only chronic), pulmonary disease, gastrointestinal, oncological, renal, orthopedic and psychiatric disorders (no vs. acute vs. chronic), addictive disorder, sepsis, obesity (BMI > 30), diabetes mellitus, type of tracheotomy (dilatational vs. surgical) and complications (none vs. pneumonia or respiratory infections vs. other infections or sepsis or other). Patients who died with a TC remained in the model. A statistical significance was assumed for effects with a p-value < 0.05.

Results

The investigated patients had a high degree of multimorbidity: In addition to neurological diseases, 90.6% of the patients had pulmonary, 64% cardiac, 39.1% psychiatric, 30% renal and 24.9% gastrointestinal acute or chronic comorbidities.

Of the 831 patients, 470 were successfully decannulated (57%). These were, on average, younger (64 vs. 67 years, p < 0.001) and had fewer common cerebral infarctions (p = 0.003), less hypoxic brain damage (p = 0.014), fewer epileptic seizures (p < 0.001) and fewer cardiac (p = 0.010) or pulmonary diseases (p = 0.018) than patients who could not be decannulated (Table 1). In addition, decannulated patients had significantly higher scores for CRS-R (19.3 ± 5.2) than nondecannulated (12.9 ± 7.7) at admission to the ERC, and were more frequently orally fed (28.7%) compared to only 4.4% of the nondecannulated patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at admission to ERC (n = 831)

| Parameters at admission | Total (n = 831) | Decannulated (n = 470) | Non-decannulated (n = 361) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD or n (%) | M ± SD or n (%) | M ± SD or n (%) | ||

| Age (years) | 65.4 ± 12.9 | 63.9 ± 12.8 | 67.3 ± 12.8 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 565 (68.0) | 303 (64.5) | 262 (72.6) | 0.013 |

| Cerebral infarction | 243 (29.2) | 118 (25.1) | 125 (34.6) | 0.003 |

| Nontraumatic hemorrhage | 210 (25.3) | 114 (24.3) | 96 (26.6) | 0.442 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 116 (14.0) | 59 (12.6) | 57 (15.8) | 0.182 |

| Hypoxia | 117 (14.1) | 54 (11.5) | 63 (17.5) | 0.014 |

| CIP/CIM | 313 (37.7) | 196 (41.7) | 117 (32.4) | 0.006 |

| Epilepsy | 137 (16.5) | 59 (12.6) | 78 (21.6) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac disease | 532 (64.0) | 294 (62.6) | 23 (65.9) | 0.315 |

| Acute or acute-chronic | 302 (36,3) | 183 (38,9) | 119 (33.0) | |

| Chronic | 232 (27.9) | 112 (23.8) | 120 (33.2) | |

| Pulmonary disease | 753 (90.6) | 416 (88.5) | 337 (93.4) | 0.018 |

| Acute or acute-chronic | 728 (87.6) | 402 (85.5) | 326 (90.3) | 0.060 |

| Chronic | 25 (3.0) | 14 (3.0) | 11 (3.0) | |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 207 (24.9) | 116 (24.7) | 91 (25.2) | 0,862 |

| Acute or acute-chronic | 152 (18.3) | 87 (18.5) | 65 (18.0) | 0.833 |

| Chronic | 55 (6.6) | 29 (6.2) | 26 (7.2) | |

| Renal disease | 249 (30.0) | 143 (30.4) | 106 (29.4) | 0.740 |

| Acute or acute-chronic | 120 (14.4) | 71 (15.1) | 49 (13.6) | 0.821 |

| Chronic | 129 (15.5) | 72 (15.3) | 57 (15.8) | |

| Psychiatric disease | 325 (39.1) | 204 (43.4) | 121 (335) | 0.001 |

| Addictive disorder | 213 (25.6) | 139 (29.6) | 74 (20.5) | 0.010 |

| Sepsis | 313 (37.7) | 174 (37.0) | 139 (38.5) | 0.662 |

| Tracheotomy technique | < 0.001 | |||

| Dilatational | 435 (52.3) | 287 (61.1) | 148 (41.0) | |

| Surgical | 396 (47.7) | 183 (38.9) | 213 (59,0) | |

| Nutrition | < 0.001 | |||

| Nasogastric tube | 346 (41.6) | 194 (41.3) | 152 (42.1) | |

| PEG | 334 (40.2) | 141 (30.0) | 193 (53.5) | |

| Oral diet | 151 (18.2) | 135 (28.7) | 16 (4.4) | |

| CRS-R | 16.6 ± 7.2 | 19.3 ± 5.2 | 12.9 ± 7.7 | < 0.001 |

Results as mean ± standard deviation or number of cases (in percent)

The patients were ventilated an average of 48.8 ± 33.2 days. The duration of ventilation was significantly longer (p < 0.001) for nondecannulated patients. In addition, nondecannulated patients were more frequently affected by complications during the rehabilitation period, especially by pneumonia and respiratory infections. One-third of the patients (32.3%) were discharged from the ERC for further rehabilitation, another third (31.3%) into a nursing home and 10.8% back to the family. 12.3% of the patients had to be transferred back to the ICU. Sixty two patients (7.5%), 58 of them in the nondecannulated group (16.1%), died in the EFC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Course of disease and outcome of ERC patients (n = 831)

| Parameters at discharge | Total (n = 831) | Decannulated (n = 470) | Non-decannulated (n = 361) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD or n (%) | M ± SD or n (%) | M ± SD or n (%) | ||

| Wearing time of TC (days) | – | 64.6 ± 36.0 | – | |

| Duration of ventilation (days) | 48.8 ± 33.2 | 43.6 ± 24.9 | 55.7 ± 40.6 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of stay in the ERC (days) | 64.2 ± 48.1 | 63.3 ± 47.2 | 65.4 ± 49.3 | 0.547 |

| Complications (existing) | 283 (33.9) | 102 (21.7) | 181 (49.9) | < 0.001 |

| Number of complications | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| Complications (type) | < 0.001 | |||

| None | 550 (66.2) | 368 (78.3) | 182 (50.4) | |

| Pneumonia / respiratory infect | 130 (15.6) | 47 (10.0) | 83 (23.0) | |

| Other infect / sepsis | 64 (7.7) | 27 (5.7) | 37 (10.2) | |

| Other | 87 (10.4) | 28 (5.9) | 59 (16.3) | |

| Nutrition | < 0.001 | |||

| Nasogastric tube | 28 (3.6) | 1 (0.2) | 27 (8.9) | |

| PEG | 295 (38.4) | 56 (12.0) | 239 (78.9) | |

| Oral diet | 446 (58.0) | 409 (87.8) | 37 (12.2) | |

| CRS-R | 19.1 ± 6.3 | 21.9 ± 2.8 | 14.6 ± 7.6 | < 0.001 |

| Recannulation | 24 (4.9) | 8 (1.7) | 16 (84.2) | < 0.001 |

| Deceased | 62 (7.5) | 4 (0.9) | 58 (16.1) | < 0.001 |

| Status at discharge | < 0.001 | |||

| Domesticity | 90 (10.8) | 70 (14.9) | 20 (5.5) | |

| Further rehabilitation | 268 (32.3) | 264 (56.2) | 4 (1.1) | |

| Nursing home | 260 (31.3) | 87 (18.5) | 173 (47.9) | |

| Relocation to the ICU | 102 (12.3) | 31 (6.6) | 71 (19.7) | |

| Other | 49 (5.9) | 14 (3.0) | 35 (9.7) | |

| Death | 62 (7.5) | 4 (0.9) | 58 (16.1) | |

Results as mean ± standard deviation or number of cases (in percent)

The likelihood of a successful decannulation was significantly reduced with increasing age (OR 0.68 per SD = 12.9 years, p < 0.001), a longer duration of mechanical ventilation (OR 0.57 per 33.2 days, p < 0.001) and complications, whereas an oral diet (OR 3.80; p < 0.001) and a higher responsivity at admission (OR 3.07 per 7.18 CRS-R points; p < 0.001) were positively associated (Fig.1).

Fig. 1.

Multicentrically assessed predictors of decannulation (n = 831; Nagelkerkes R2 = 0,465). SD = standard deviation; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; PNP/MP = polyneuro−/myopathy

Discussion

In the present study, a large, tracheostomized patient collective in ERCs was investigated multicentrically for the first time. In addition to neurological diseases, these patients also had a wide range of internal medicine related diseases; independently, more than half of the patients could be weaned from the TC. Besides proving a high decannulation rate, it was also possible to specify predictors which could be easily assessed. Not only age and sex, but also the tracheotomy technique, as well as the level of alertness or responsivity and an oral diet at admission to the ERC were prognostically important. Complications during early rehabilitation had a limiting effect.

Age and sex

While age in other studies [5, 7] had an effect on decannulation (younger patients had a higher probability of decannulation than older ones), the negative association with the male sex was rather unexpected. For example, a recent review of sex differences after stroke [8] shows a better functional outcome for male patients, as does a recent study [9] in geriatric patients after stroke (n = 919, 56% male), from which at least 55% of our patients suffered. However, nearly 70% of all patients in our study were male, which could have led to a bias.

Cardiac diseases

Heart diseases also had an effect, whereby patients had a higher decannulation rate when cardiac disease was acute compared to chronic. One possible explanation for this could be the high prevalence of cognitive impairments that have an influence on voluntary secretion management and food intake (e.g., in terms of attentional focus or executive planning). For example, 50% of the patients experienced postoperative delirium after bypass surgery [10] and 25–74% of the chronic cardiac patients were cognitively impaired [11].

Technique of tracheotomy

Patients with a dilatational tracheotomy had a 66% higher probability of decannulation than patients with a surgical tracheotomy. Numerous studies support our finding by showing a lower complication rate (e.g. fewer postoperative infections or less peristomal bleeding) for dilatational tracheotomy [12–15]. In addition, long-term complications such as tracheal stenosis are also less frequent after dilatational tracheotomy [16, 17]. On which basis the specific tracheotomy technique was chosen in the ICU cannot be assessed. Our data show a clear superiority of the dilatation tracheotomy with respect to decannulation.

Complications

A high predictive value for decannulation had complications during the rehabilitation period. These included pneumonia and respiratory infections, which in tracheotomized patients can be caused by aspiration [18], and bacterial colonization after tracheotomy [19], but also by the TC itself [20]. Other complications, such as laryngeal edema, tracheomalacia, or tracheal stenosis, were astonishingly rare in the patients observed here compared to other studies [21], but did have an effect on decannulation.

Duration of mechanical ventilation

In other studies, the duration of mechanical ventilation also had a negative effect on decannulation and on the patient‘s functional status at discharge [22]. With regard to weaning from the TC, we assume above all a negative influence on swallowing functions. Even a prolonged endotracheal intubation (≥ 48 h) is an independent predictor of dysphagia [23, 24] and leads to severe and persistent dysphagia with aspiration, independently of the underlying critical illness [25]. Also, the cuffed TC itself has a negative impact on deglutition: Above all, the absence of a physiological airflow through larynx, pharynx, nose and mouth is problematic because it is an important stimulus for spontaneous swallowing. Furthermore, the TC leads to a ubiquitous sensory impairment due to a lack of stimulation of chemo- and pressure receptors in the laryngeal mucosa. The longer the physiological airflow is interrupted by invasive mechanical ventilation, the more seriously deglutition processes can be impaired, which in turn requires a cuffed TC to protect the lower airways from aspiration [26]. Decannulation is therefore highly dependent on the extent to which swallowing functions (through physiological airflow control and dysphagia therapy) are improved.

Nutrition / dysphagia

The type of feeding at admission to the ERC (through nasogastric tube, PEG or orally) had a significant influence on decannulation. Patients who had already had a PEG at admission could not be decannulated to a large extent compared to patients who took an oral diet. In this connection, the type of diet reflects the severity of swallowing. Dysphagia may be the result of neurological damage in areas relevant for swallowing or of the cuffed TC itself [27]. Since all invasively mechanically ventilated patients are at high risk for the development of dysphagia with aspiration, an exhaustive instrument-based or clinical swallowing test should be performed prior to oral feeding [26]; however, the decision criteria for the onset of an oral diet in the ICU were not collected, so that it cannot be ruled out that among the patients with oral diet at admission to the ERC were some with severe dysphagia.

Alertness

A further predictor was the level of alertness / responsivity at admission to the ERC, which was assessed by CRS-R [28]. Decannulated patients had a significantly higher scale value at admission than nondecannulated patients. Presumably, alertness has a direct impact on other functions, such as safe food intake or effective secretion management. In patients with traumatic brain injury (n = 20, 80% male, age group 21–85), a close relationship was found between the level of consciousness and the probability of decannulation. A reduced awareness was associated with dysphagia, aspiration and pneumonia [27]. However, a significant influence could not be shown in all studies [3]. Moreover, “alertness” is difficult to operationalize. In assessments such as the CRS-R, parameters like attention or object recognition are quantified quantitatively by means of verbal and motor responses, which can be limited by peripheral or central paresis, disorientation, delirium or reduced instructional comprehension in critically ill patients. It is possible that the CRS-R parameter is an indicator of the severity of the cerebral disease per se, which limits consciousness and all levels of function.

Critical illness polyneuro−/myopathy (CIP / CIM)

CIP and CIM are frequent complications in critically ill patients and affect the motor and sensory axons of the peripheral nervous system. An important risk factor is sepsis [29], which occurred in 37.7% of the patients examined here. A current electrophysiological study [30] on the frequency of CIP / CIM in early rehabilitation patients (n = 782) was able to demonstrate it in almost 70% of cases; the ventilation duration was significantly increased (p < 0.001), with an average of 32.1 days vs. 20.6 days in patients without CIP / CIM. In accordance with that, in our study patients with CIP / CIM could be decannulated significantly less frequently than patients without. The severity of the CIP / CIM may also have had an influence (e.g., on coughing and swallowing), but this has not been assessed.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. Thus, the severity of the neurological and other critical illnesses and comorbidities which could have an effect on decannulation with regard to the resulting dysphagia was not assessed [31]. Also, parameters from the ICU (e.g., ventilation pressure or criteria for the tracheotomy technique used or the start of oral diet) were not available, so that their influence on decannulation could not be determined. In addition, some variables that had an influence on the decannulation in other studies or were difficult to objectify were not assessed, such as recurrent vomiting [7], the effectiveness of coughing, tracheal secretion or the therapeutic approach for decannulation. Also, parameters that reflect motor function (strength, mobilization, ability to sit up, etc.) that are important for swallowing were not collected, as motor scores were not a part of the routine procedure at four of the five participating clinics. Since no follow-up was carried out after the patients were discharged from the ERC, it is impossible to say whether patients had to be recannulated after this period. The number of recannulations required during the observation period itself was very low, affecting only 24 patients (4.9%) of whom 16 could not be decannulated.

Conclusions

In the present study, predictors of decannulation from medical routine data could be determined in a large number of patients. Many of these parameters are already available at admission to the ERC and provide evidence of successful decannulation very early. In particular, patients with an oral diet, dilatational tracheotomy or high responsivity have a favorable prognosis. On the other hand, complications that occur during early rehabilitation should be given great attention in order not to threaten the success of the decannulation. Potentially modifiable predictors (alertness / responsiveness, swallowing) should be the therapeutic focus of the NNFR. Prospectively, an investigation on the predictive value of the predictors would be desirable in a setting outside the EFC, e.g., in the case of patients who are permanently provided with a TC in the outpatient area.

Acknowledgements

Authors’ contribution

MDH designed the study and drafted the manuscript. AS performed the data and statistical analysis. AS, MJ, OL, CD, MS, AvH and HV participated in the conception and design of the study, WH helped to draft the manuscript. HV performed the quality assessment and helped to revise the manuscript. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the study results. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was financed by AOK Nordost. The funding played no role in the design of the study, data analysis, interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets that were used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from A. Salzwedel on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CIP/CIM

Critical illness polyneuro−/myopathy

- CRS-R

Coma Recovery Scale-Revised

- ERC

Early rehabilitation clinic

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- TC

Tracheal cannula

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical permission was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Potsdam (13 / 36. Meeting 5th of May 2014). Since only routine medical data were collected and evaluated anonymously and no interventions were carried out, patients consent to participate was not required. The routine data were documented at the participating clinics without personal data. Furthermore, the purpose of the research project could not be achieved by other means. Therefore, the ethical review board of the University of Potsdam according to §§31, 32 BbgKHEG (Brandenburg Hospital Development Act) and §25 Berlin LKG (Berlin State Hospital Law) has waived the need for patients’ consent to participate.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maria-Dorothea Heidler, Phone: +0049 33397 34134, Email: heidler@brandenburgklinik.de.

Annett Salzwedel, Email: ansal@uni-potsdam.de.

Michael Jöbges, Email: joebges@brandenburgklinik.de.

Olaf Lück, Email: lueck@rehaklinik-beelitz.de.

Christian Dohle, Email: christian.dohle@median-kliniken.de.

Michael Seifert, Email: michael.seifert@median-kliniken.de.

Andrea von Helden, Email: Andrea.helden@vivantes.de.

Wibke Hollweg, Email: hollweg@ash-berlin.eu.

Heinz Völler, Email: heinz.voeller@uni-potsdam.de.

References

- 1.Pohl M, Bertram M, Bucka C, Hartwich M, Jöbges M, Ketter G, et al. Rehabilitationsverlauf von Patienten in der neurologisch-neurochirurgischen Frührehabilitation. Ergebnisse einer multizentrischen Erfassung im Jahr 2014 in Deutschland. Nervenarzt. 2016;87:634–644. doi: 10.1007/s00115-016-0093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bach JR, Saporito LR. Criteria for extubation and tracheostomy tube removal for patients with ventilator failure. Chest. 1996;110:1566–1571. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.6.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan LYY, Jones AYM, Chung RCK, Hung KN. Peak flow rate during induced cough: a predictor of successful decannulation of a tracheotomy tube in neurosurgical patients. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19:278–284. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lima CA, Siqueira TB, da Fonseca Travassos E, Gomes Macedo CM, Bezerra AL, Siqueira MD, et al. Influence of peripheral muscle strength on the decannulation success rate. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2011;23:56–61. doi: 10.1590/S0103-507X2011000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santus P, Gramegna A, Radavanovic D, Raccanelli R, Valenti V, Rabbiose D, et al. A systematic review on tracheostomy decannulation: a proposal of a quantitative semiquantitative clinical score. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidler MD, Salzwedel A, Liero H, Jöbges M, Völler H. Decannulation of critically ill patients after long-term mechanical ventilation – predictors from clinical routine data. Adv Rehab. 2014;3:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ledl C, Wagner-Sonntag E. Qualitäts management in der neurologischen Früh rehabilitation: Dekanülierungsquoten und Ursachen der Nicht-Dekanülierbarkeit bei neurogener Dysphagie. Neurol Rehabil 2016; Suppl 1:S10.

- 8.Reeves MJ, Bushnell CD, Howard G, Gargano JW, Duncan PW, Khatwoda A, et al. Sex differences in stroke: epidemiology, clinical presentation, medical care, and outcomes. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:915–926. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70193-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizrahi EH, Waitzman A, Arad M, Adunska A. Gender and the functional outcome of elderly ischemic stroke patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:438–441. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, Gaver V, Grocott H, Jones RH, et al. Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:395–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogels RLC, Scheltens P, Schroeder-Tanka JM, Weinstein HC. Cognitive impairment in heart failure: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng E, Fee WE. Dilatational versus standard tracheostomy: a meta-analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:803–807. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman BD, Isabella K, Lin N, Buchman TG. A meta-analysis of prospective trials comparing percutaneous and surgical tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Chest. 2000;118:1412–1418. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.5.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins KM, Punthakee X. Meta-analysis comparison of open versus percutaneous tracheostomy. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:447–454. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000251585.31778.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youssef TF, Ahmed MR, Saber A. Percutaneous dilatational versus conventional surgical tracheostomy in intensive care patients. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3:508–512. doi: 10.4297/najms.2011.3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heffner JE, Miller KS, Sahn SA. Tracheostomy in the intensive care unit. Part 2: complications. Chest. 1986;90:430–436. doi: 10.1378/chest.90.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marelli D, Paul A, Manolidis S, Walsh G, Odim JNK, Burdon TA, et al. Endoscopic guided percutaneous tracheostomy: early results of a consecutive trial. J Trauma. 1990;30:433–435. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199004000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leder SB. Incidence and type of aspiration in acute care patients requiring mechanical ventilation via a new tracheotomy. Chest. 2002;122:1721–1726. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.5.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rello J, Lorente C, Diaz E, Bodi M, Boque C, Sandiumenge A, et al. Incidence, etiology, and outcome of nosocomial pneumonia in ICU patients requiring percutaneous tracheotomy for mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2003;124:2239–2243. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim EH, Tracy L, Hill C, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. The occurrence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a community hospital: risk factors and clinical outcomes. Chest. 2001;120:555–561. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norwood S, Vallina VL, Short K, Saiqusa M, Fernandez LG, McLarty JW. Incidence of tracheal stenosis and other late complications after percutaneous tracheostomy. Ann Surg. 2000;232:233–241. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200008000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sansone GR, Frengley JD, Vecchione JJ, Manogaram MG, Kaner RJ. Relationship of the duration of ventilator support to successful weaning and other clinical outcomes in 437 prolonged mechanical ventilation patients. J Intensive Care Med. 2017;32:283–291. doi: 10.1177/0885066615626897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barker J, Martino R, Reichardt B, Hickey EJ, Ralph-Edwards A. Incidence and impact of dysphagia in patients receiving prolonged endotracheal intubation after cardiac surgery. CJS. 2009;52:119–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferraris VA, Ferraris SP, Moritz DM, Welch S. Oropharyngeal dysphagia after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1792–1795. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)02640-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skoretz SA, Flowers HL, Martino R. The incidence of dysphagia following endotracheal intubation. Chest. 2010;137:665–673. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heidler MD, Bidu L, Friedrich N, Völler H. Oralisierung langzeitbeatmeter Patienten mit Trachealkanüle. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2015;1:55–60. doi: 10.1007/s00063-014-0397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanata I, Sansots RS, Hirata GC. Tracheal decannulation protocol in patients affected by traumatic brain injury. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;18:108–114. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giacino JT, Kalmar K. CRS-R. Coma recovery scale-revised. Administration and Scoring Guidelines www.coma.ulg.ac.be/images/crs_r.pdf. Accessed 13 Jul 2017.

- 29.Hermans G, De Jonghe B, Bruyninckx F, Van den Berghe G. Clinical review: critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy. Crit Care. 2008;6:238. doi: 10.1186/cc7100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schorl M, Valerius-Kukula SJ, Kemmer TP. Critical-Illness-Polyneuropathie bei Patienten in der neurologisch-neurochirurgischen Frührehabilitation – Häufigkeit und Auswirkungen auf die Beatmungsentwöhnung. Neurol Rehabil. 2012;18:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li S, Zhou M, Yu B, Ma Z, Chen S, Gong Q, et al. Altered default mode and affective network connectivity in stroke patients with and without dysphagia. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:126–131. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets that were used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from A. Salzwedel on reasonable request.