Abstract

The use of online resources by patients for their daily health needs has escalated with the proliferation of mobile devices and mobile apps. While healthcare professionals can help their patients access quality online resources and tools, they may not have received the education and training to do this effectively. To meet this educational need, a daylong workshop was developed at a health sciences university that aimed to increase awareness of students in various health disciplines of mobile health-related apps and federally sponsored websites that provide patient-friendly medical information.

Keywords: mHealth, medical education, digital health, interprofessional education

Introduction

The widespread availability and adoption of mobile devices (e.g. smartphones, tablet computers) has made it possible for patients to access health information online. Many organizations, both professional and private, are leveraging their online presence to attract patients to utilize their websites and information in their personal care, including access to medical records, mobile applications (“apps”) to improve health and wellness, and wearable devices to monitor health in real-time. While free medical information is a positive element in the digital healthcare age, there are several areas of concern pertaining to patients’ digital health literacy and the reliability of online health information.1,2

Foremost, clinicians are concerned the information patients may access online is incorrect or inaccurate and may lead to patients inferring or seeking improper treatment.3,4 There have been reports of websites marketing products and services online that have confused patients.3,5 Another area of concern is the dramatic rise in the number of apps developed particularly to increase patients’ autonomy over their health. While these health-related apps might be as simple as exercise and dieting apps, they also include apps that purport to help patients monitor and manage chronic as well as acute illnesses. Several health-related apps have been found to be of questionable nature;6–9 some have been removed from mobile app stores due to litigation of their content.10

While the questions related to the use of mobile technology and the Internet as health information resources for patients are unlikely to dissipate, the reality is these new and other emerging tools are becoming integral components of patient care, and use of online health resources will most likely be tied to health outcomes.11 As such, current and future members of the healthcare workforce must be prepared to answer questions related to health information patients may find online or desire input on. For this reason, we created a workshop for health professions students to educate them on these issues, raise their awareness of online resources for easy-to-read, reliable health information, and engage them in interdisciplinary learning and discussions. We wanted to explore whether this endeavor should be integrated in the training of health professions students or be part of an expanded program related to issues in the digital health sphere.

Methods

Workshop design and implementation

We created and facilitated a one-day workshop “Patients’ Health Information Needs: Are You Ready to Serve?” for Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences University – Worcester students in different health disciplines (pharmacy, nursing, optometry, physical therapy, and physician assistant studies). The primary objectives of the workshop were (1) to improve the knowledge and exposure of participants to MedlinePlus and other National Library of Medicine (NLM) online materials and (2) review and identify key components of mobile health-related apps. To promote the workshop, an email was sent to all the deans of the different degree programs requesting their assistance in advertising the workshop. Mini-posters and flyers were posted around campus. An email blast was sent to students; students were asked to respond to the email to reserve one of the 50 workshop spots. To ensure an interprofessional mix of students and due to the asynchronous schedules among the degree programs during the week, the workshop was scheduled on a Saturday from 9:00 am to 2:30 pm (with a 30-minute lunch break). It was held in a computer classroom that had 44 desktop computers; students were encouraged to bring their laptop and/or mobile devices. Pre- and post-workshop surveys were used to collect students’ demographic data, and knowledge and experience gained from the workshop. The surveys were approved by the institution’s Institutional Review Board. Data were analyzed and reported using descriptive statistics.

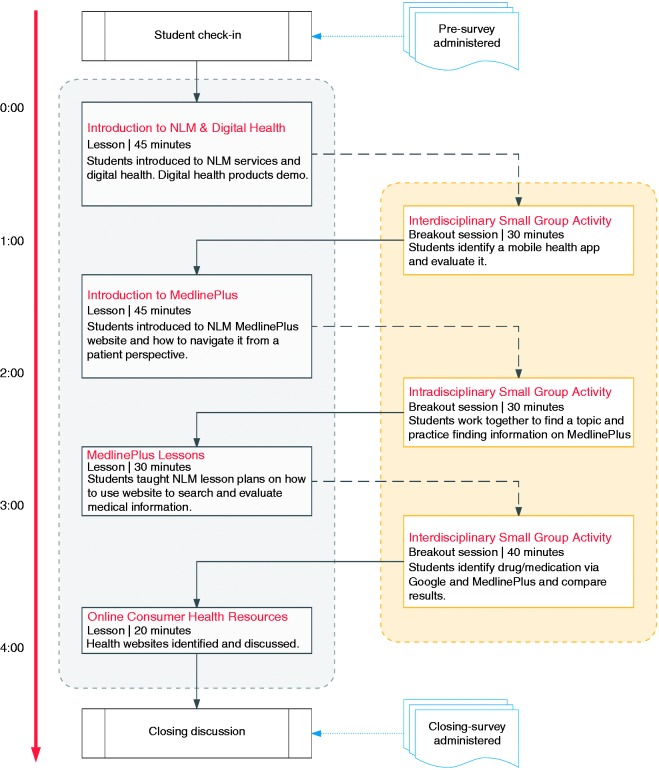

The overall design of the workshop is detailed in Figure 1. The hands-on workshop had two major components: (1) exploration and evaluation of NLM and other mobile apps for smart devices as well as digital health devices (e.g. Fitbit, Bluetooth enabled blood pressure cuffs) and (2) introduction to MedlinePlus (www.medlineplus.gov) and its features and other NLM online resources. Hands-on activities were designed to provide students opportunities to interact and work in intradisciplinary and interdisciplinary groups. As seen in Figure 1, the workshop started with a didactic lesson introducing the issues of online health information and the rise of digital health services in healthcare, followed by a demonstration of how to navigate mobile health apps and use selected digital health devices. Students then broke into groups to identify and review a mobile health app using a rubric, and then discussing their findings with other groups.12–14 The next didactic lesson focused on NLM MedlinePlus; students were given two lessons – introduction to the website and its utility for addressing patients’ online health information needs. Students once again split into groups performing disease-related online searches using MedlinePlus, and presenting and sharing their findings and thought processes. Discussions focused on the pros and cons of using general search engines (i.e. Google) versus MedlinePlus and other identified reliable health websites (MLA’s top 10 health websites); the discussions were intended to promote student awareness of quality health information websites. The workshop then closed out with an overall general discussion on what digital health means for each health discipline and how students may help patients identify online resources and digital health services for their own personal care.

Figure 1.

Digital Health Workshop: Activity layout of lessons and breakout sessions.

Results

Forty-seven students attended the workshop (38 pharmacy, two physical therapy, four optometry, and three nursing). Table 1 shows the students’ age distribution and their top five responses to pre-workshop survey questions pertaining to health information websites they consult and mobile apps they have downloaded on their mobile devices. The results show students were utilizing websites and apps in their daily roles and duties as students in their clinical rotations, however, NLM online resources or mobile health-related apps were mentioned minimally. Of the 104 written responses to the open-ended question about health information websites, “Lexicomp” was the most popular answer (23.1%), only three students (2.9%) wrote “MedlinePlus”. Of the 78 written responses to the open-ended question about mobile apps, “Micromedex” was the most popular answer (21.8%). Table 2 shows students’ confidence levels in their ability to perform certain tasks related to the provision of health information. Two-thirds (66.7%) of students felt “Very confident” or “Confident” answering patients’ questions in lay or plain language; in contrast, students were not as confident in their abilities to address patients’ needs for quality health information using online resources or mobile apps. As seen in Table 3, the students gained knowledge and confidence from the workshop. They were more aware of MedlinePlus and its features and felt more confident recommending it to patients who were seeking reliable online health information resources. Overall, more than 90% of the students rated the workshop and its components “Very Effective” or “Effective”. Informal feedback from the students at the end of the workshop indicated they enjoyed being a part of it and recommended we offer the workshop again.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographics and pre-workshop survey responses

| n = 47 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Health Discipline | ||

| Nursing (Post-BSN) | 3 | 6.4% |

| Optometry | 4 | 8.5% |

| Pharmacy | 38 | 80.9% |

| Physical Therapy | 2 | 4.3% |

| n = 45 | % | |

| Age Range | ||

| 40 to 35 | 4 | 8.8% |

| 34 to 30 | 8 | 17.8% |

| 29 to 25 | 27 | 60.0% |

| 24 to 20 | 6 | 13.3% |

| Pre-workshop: Top 5 websites used by students to find quality online health information (total written responses = 104) | ||

| Lexicomp | 24 | |

| PubMed | 17 | |

| WebMD | 12 | |

| 9 | ||

| Mayo Clinic | 6 | |

| Pre-workshop: Top 5 health/medical apps students have downloaded on their mobile device (total written responses = 78) | ||

| Micromedex | 17 | |

| Lexicomp | 13 | |

| Medscape | 7 | |

| Epocrates | 6 | |

| WebMD | 5 | |

Table 2.

Pre-workshop survey responses

| Task | Very confident | Confident | Slightly confident | Not at all confident |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-workshop: Students’ confidence level in performing certain tasks* (n = 42) | ||||

| Answering patients’ questions using lay or plain language | 11.9% | 54.8% | 21.4% | 11.9% |

| Teaching a community group how to find quality health information websites | 7.1% | 19.0% | 31.0% | 42.9% |

| Teaching a patient how to navigate a quality health information website | 16.7% | 23.8% | 35.7% | 23.8% |

| Identifying quality mobile medical apps for patients | 9.5% | 23.8% | 28.6% | 38.1% |

Table 3.

Participants’ post-workshop survey responses

| Workshop Objectives | n | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratings of workshop* | ||||||

| I am more aware of the main features of MedlinePlus. | 46 | 89.1% | 10.9% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| I am more confident answering patients’ questions using lay or plain language. | 47 | 74.5% | 21.3% | 4.3% | 0% | 0% |

| I am more confident in teaching a patient, on a one-on-one basis, how to navigate MedlinePlus to get answers to his/her questions. | 47 | 72.3% | 27.7% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| I am more confident in teaching a community group class about MedlinePlus and its features. | 47 | 70.2% | 23.4% | 6.4% | 0% | 0% |

| I am more confident in teaching a community group class how to find reliable health information websites. | 47 | 63.8% | 29.8% | 6.4% | 0% | 0% |

| I am more aware of NLM and other reliable mobile health/medical apps. | 47 | 74.5 | 23.4% | 2.1% | 0% | 0% |

| Very Effective | Effective | Neutral | Not Effective | Not at all Effective | ||

| Ratings of workshop components** (n = 47) | ||||||

| Simulation of MedlinePlus presentation | 53.2% | 42.6% | 4.3% | 0% | 0% | |

| Intradisciplinary small group activity | 55.3% | 42.6% | 2.1% | 0% | 0% | |

| Interdisciplinary small group activity | 53.2% | 42.6% | 4.3% | 0% | 0% | |

| Lectures/Overviews (e.g. MedlinePlus Lessons, NLM Mobile Apps) | 63.8% | 31.9% | 4.3% | 0% | 0% | |

| Binder/Handouts | 55.3% | 36.2% | 8.5% | 0% | 0% | |

5-point Likert scale: Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, Strongly Disagree.

5-point Likert scale: Very Effective, Effective, Neutral, Not effective, Not at all effective.

Discussion

Overall, we met our primary objectives for the workshop. One strength of this workshop was that the material was relevant across the spectrum of health professions; the phenomenal rise of digital health innovations permeates all health areas. The interprofessional and interdisciplinary workshop activities allowed students to focus on what they knew, based on their educational background and preparation, to apply it in a different context, and to share their findings with others. The activities further encouraged identification and knowledge of professional roles and responsibilities that may be useful in future clinical practice.

The design of the workshop allows speakers and presenters with any healthcare background to present it, as long as they are knowledgeable about the digital health space. It is amenable to being updated constantly as new information on health websites or health-related apps becomes available.

Interprofessional education (IPE) continues to play a prominent role in health professions education and accreditation standards.15 Finding a topic or content area to meet this requirement may be challenging. As we have demonstrated, however, one possibility is to educate future health professionals about how to address patients’ needs for reliable health information using online resources and technology. This does not rely heavily on an educator’s clinical acumen. It relies on technology (e.g. mobile devices) many students already have access to. Other than faculty time, minimal cost was associated with the workshop (e.g. printing, binders). Healthcare programs interested in expanding IPE opportunities in their curriculum may find it easy to adopt and adapt this workshop.

One limitation of our results was that the workshop facilitators were all pharmacy educators. This may have affected the extent of promotion and advertising of the workshop to other health disciplines and subsequently led to the low turnout of students from other health disciplines. Going forward, the workshop would benefit from inclusion of educators from other health disciplines to share their perspectives and experiences. This may increase the diversity of students in attendance knowing their faculty members are involved in the workshop.

Conclusion

The rise of digital health technologies and access to online health information by patients requires health professions students to be prepared to address their future patients’ needs. A workshop focused on digital health technologies is a novel experience for students and can be utilized as an interprofessional educational opportunity. Based upon our exploratory research here, a digital health workshop may be beneficial for healthcare programs to integrate into their curriculum as an IPE activity and to increase knowledge and experience in an increasingly technologically reliant healthcare space. Future research will be required to determine the impact of such workshops or integration of material into the curriculum on student outcomes. Educators looking to emulate our experience would be advised to create a diverse group of workshop leaders with experience in digital health.

Contributorship

TDA, ML, and PE all equally contributed to the design of this intervention and carrying it out. ML was involved in gaining ethical approval and data analysis. TDA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

The surveys and data collected were approved by the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project has been funded in part with Federal funds from the Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, under Subcontract No. HHSN-276-2011-000-10C with the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.

Guarantor

TDA.

Peer review

This manuscript was reviewed by two reviewers, the author(s) have elected for these individuals to remain anonymous.

References

- 1.Bhavnani SP, Narula J, Sengupta PP. Mobile technology and the digitization of healthcare. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 1428–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amante DJ, Hogan TP, Pagoto SL, et al. Access to care and use of the Internet to search for health information: results from the US National Health Interview Survey. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rehman J. Accuracy of medical information on the Internet, http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/accuracy-of-medical-information-on-the-internet/ (2012, accessed 1 July 2016).

- 4.Kitchens B, Harle CA, Li S. Quality of health-related online search results. Decis Support Sys 2014; 57: 454–462. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agboola SO, Bates DW, Kvedar JC. Digital health and patient safety. JAMA 2016; 315: 1697–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semigran HL, Linder JA, Gidengil C, et al. Evaluation of symptom checkers for self diagnosis and triage: audit study. BMJ 2015; 351: h3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blenner SR, Köllmer M, Rouse AJ, et al. Privacy policies of Android diabetes apps and sharing of health information. JAMA 2016; 315: 1051–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plante TB, Urrea B, Macfarlane ZT, et al. Validation of the Instant Blood Pressure smartphone app. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176(5): 700–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huckvale K, Prieto JT, Tilney M, et al. Unaddressed privacy risks in accredited health and wellness apps: a cross-sectional systematic assessment. BMC Med 2015; 13: 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Federal Trade Commission. FTC approves final settlement orders against marketers who claimed their mobile apps could cure acne, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2011/10/ftc-approves-final-settlement-orders-against-marketers-who (2011, accessed 1 July 2016).

- 11.Hone T, Palladino R, Filippidis FT. Association of searching for health-related information online with self-rated health in the European Union. Eur J Public Health 2016; 26(5): 748–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanrahan C, Aungst TD and Cole S. Evaluating mobile medical applications. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 2014.

- 13.Rodis J, Aungst TD, Brown NV, et al. Enhancing pharmacy student learning and perceptions of medical apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016; 4: e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miranda AC, Serag-Bolos ES, Aungst TD, et al. A mobile health technology workshop to evaluate available technologies and their potential use in pharmacy practice. BMJ STEL 2016; 2: 23–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2011.