Abstract

Objective

Although social anxiety disorder is a persistent and debilitating condition, only a minority of people with social anxiety disorder seek help and little is known about methods for promoting help seeking for social anxiety disorder. This pilot trial explored the potential effectiveness of an online program designed to increase help-seeking intentions for social anxiety disorder.

Methods

Australian adults with symptoms of untreated social anxiety disorder were recruited online and randomised to either the Shyness Information Online intervention (n = 41) or an online attention control condition (n = 41). Each program together with a baseline and postintervention survey was delivered in one session. The primary outcome was intentions to seek help from a professional. Secondary measures included anxiety literacy, help-seeking attitudes, internalised stigma, and perceived need for treatment. The acceptability of the program content and feasibility of the recruitment method were also examined.

Results

Although they did not demonstrate a significantly greater increase in help-seeking intentions relative to the control group (p = 0.097), those receiving the intervention showed more favourable attitudes towards seeking psychological help (Hedges’g = 0.38; p = 0.025) and a higher level of perceived need for treatment (p ≤ 0.001). Participants also showed a greater knowledge about social anxiety disorder at post-intervention than the control participants (adjusted Hedges’ g = 0.46, p < 0.001). Most respondents were satisfied with the intervention content; the recruitment strategy appeared feasible.

Conclusions

Further investigation of the intervention is warranted to test its effectiveness, explore the relationships between factors that influence social anxiety disorder help-seeking behaviour and to further test the validity of the social anxiety disorder help-seeking model on which the intervention was based.

Keywords: Social anxiety disorder, help seeking, intervention study, mental health literacy, stigma

Introduction

Social Anxiety Disorder (SAnD) is a common and debilitating condition characterised by persistent, excessive fear in social and performance situations together with avoidance or substantial distress and impaired role functioning.1

The negative impact of SAnD on the individual’s life is profound. For example, the work loss index for pure SAnD is as great as the index for pure depression and exceeds that for diabetes or heart disease.2 Moreover, sub-threshold social anxiety is also associated with substantial disability.3

Despite its disabling effects, SAnD is associated with delayed, low levels of help seeking. The estimated average time from onset of the condition to help seeking for SAnD is 16 years4 and a multi-country study of individuals from nine high income countries found that only 21% of those who satisfied the criteria for SAnD had sought professional help for the condition.5 Further, it has been reported that help seeking among individuals with SAnD is often triggered by comorbid disorders which accompany SAnD (such as depression) rather than social anxiety itself.6,7

Given the debilitating effects of SAnD and the availability of effective psychological interventions for its treatment8 there would be substantial individual and public health benefit in promoting timely evidence-based help seeking for SAnD.9 Indeed, according to calculations undertaken by Andrews and colleagues,10 disability burden associated with optimal treatment for SAnD could be reduced by 49% with 100% optimal treatment coverage and by 34% with 70% coverage.

However, there are few published empirical studies to guide public health initiatives to facilitate help seeking for SAnD. To our knowledge, with the exception of a small pilot study (n = 27) of intensive face-to-face motivation enhancement therapy (MET),11 there have been no published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions designed to promote help seeking for SAnD.12 However, as noted by Griffiths,9 two retrospective self-report studies have investigated factors that impede help seeking.13,14 Based on this and other evidence in the literature, Griffiths9 proposed a guiding framework for the development of an intervention to increase help seeking for SAnD. The framework posits that ‘the likelihood of help seeking for SAnD will be a function of knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, the availability of help, and the extent to which the illness itself impedes help seeking, and intentions to seek help’ (p.901) and that intervening to modify these factors will increase help-seeking intentions and behaviours. Further, in describing this framework, Griffiths highlighted the distinct potential of the Internet as a mode of delivery for circumventing many of the barriers to help seeking for SAnD arguing that this medium not only provides an accessible, cost-effective, scalable device for reaching those with the condition, but it also circumvents the barrier to help-seeking associated with the avoidance of face-to-face contact which is intrinsic to the illness. Finally, it was suggested that the Internet has the potential to play a key role in reducing the treatment gap for SAnD by enabling the seamless (and instant) connection from a help-promotion intervention to an evidence-based online therapy program.

Accordingly, we report here the effectiveness and acceptability of a pilot version of a multi-component intervention (Shyness Information Online), the content of which was based on Griffith’s9 framework. The aims of the study were to explore: (a) the effectiveness of Shyness Information Online in increasing help-seeking intentions among people with untreated SAnD (primary aim); (b) the effectiveness of the intervention on help-seeking attitudes, SAnD literacy and SAnD internalised stigma (secondary aims); (c) the acceptability of the program content; (d) the feasibility of recruitment for a full-scale trial via Facebook; and (e) the effect sizes of the primary outcome variable to inform the design of a subsequent fully-powered RCT.

Method

The study was a two-armed parallel randomised controlled trial. The baseline survey, program delivery, and post-intervention survey were delivered online in a single unguided session. The surveys were delivered using LimeSurvey which together with the intervention were hosted on web servers at the Australian National University (ANU).

The protocol for the study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at The Australian National University (protocol number 2014/739) and the trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12614001314617).

Randomisation and allocation concealment

Participants were randomised using an automated computer generated algorithm within LimeSurvey. No block or stratification restrictions were applied. Data analysts were not blinded to the condition allocation. Participants were not informed of the primary outcome of interest; nor were they advised that one of the conditions served as a control (see below).

Participant recruitment and procedure

Participants self-selected into the trial by clicking on a paid advertisement on Facebook. The advertisement was displayed for 11 non-consecutive days (14 January 2015–20 January 2015 and 23 January 2015–26 January 2015 inclusive) and was restricted to people who reported that they were aged 18 years or older, spoke English, and resided in Australia. The advertisement read ‘Shy? Do you avoid attention, social situations, public speaking? Please help our research.’ A ‘Learn More’ button directed potential participants to an ANU web server that contained the study briefing material.

The briefing material included general information about the study, confidentiality and privacy information, contact details of the study staff, and contact sources for participants if in distress. To mask the true intentions of the study the briefing material did not indicate that the aim of the trial was to increase help-seeking intentions. Participants were informed that the trial aimed to seek their opinion about shyness, and to evaluate the content of one of two educational programs; a program about shyness or a program about health and wellbeing. Participants were informed that group allocation would be by random assignment.

As the baseline survey, study program and post-intervention survey were administered continuously, participants did not register logon details and were anonymous. Participants received access to the baseline survey and upon completion of all survey items were randomised into one of the two study conditions. Access to the post-intervention survey was made available only on completion of the program. The time anticipated for a participant to complete the program and both surveys was a maximum of 60 min. Participants received no financial incentive for participation.

Study inclusion

All interested individuals who were aged over 18 years and provided consent were permitted to undertake the surveys and access the intervention. However, consistent with the protocol specified on the trials register, only responses from participants who reported a social anxiety score indicative of social phobia as measured by the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN)15 score ≥19 or Social Phobia Screener (SOPHS) item-based clinical criteria,16 and not seeking help or taking medication for social anxiety at the time of the trial were included in the analyses. Further, it was determined a priori to undertake separate analyses for those satisfying the SPIN and SOPHS criteria (see Analyses section). These parallel analyses were designed with the aim of examining the relative utility of the newly-developed SOPHS and the more widely adopted SPIN measure for this type of trial with a view to selecting a screening test for the fully-powered trial.

Trial conditions

Shyness Information Online

The intervention was a text-based online multiple component program based on the key themes predicted to increase help-seeking behaviour, as identified in the SAnD Help-seeking Behaviour Framework.9 The themes were literacy, stigma reduction, normative feedback, help-seeking information and motivational interviewing. The content covered for each theme is shown in Table 1. The program information was presented across 21 linear pages and included three interactive tasks. The estimated time to complete the program was 40 min. Following the post-intervention survey, participants were offered the opportunity to access an online social anxiety treatment program that has been demonstrated to reduce social anxiety symptoms.17

Table 1.

Help-seeking elements in the Shyness Information Online program. All elements were text-based.

| Element | Content |

|---|---|

| 1. Literacy | Information about SAnD diagnosis (including DSM-IV criteria), prevalence, disability, risk factors, and evidence-based medical, psychological and lifestyle treatments (each discussed under the headings What is it? Does it work? Where do you get it? and accompanied by key references). |

| 2. Stigma reduction | Information designed to counter myths about SAnD (e.g., The myth ‘Social anxiety is not a real condition’ was countered with evidence from genetic and brain imaging studies). |

| 3. Normative feedback | Feedback about social anxiety level based on responses to the SOPHS. |

| 4. Help-seeking information | Information about where and how to seek help including face-to-face conventional help and online self-help; an exercise to develop a step-by-step plan to seek help. |

| 5. Motivational interviewing | A challenge of the mindset that shyness cannot be changed and an exercise where participants listed the pros and cons of seeking and not seeking treatment for SAnD. |

SAnD: Social Anxiety Disorder; SOPHS: Social Phobia Screener.

Health and wellbeing attention control

The educational control program provided information about physical activity adapted from US and Australian evidence-based physical activity guidelines.18,19 It was of a similar length to the Shyness Information Online program and also included interactive exercises. Following the post-intervention survey, individuals in the control group were offered the opportunity to access the Shyness Information Online program.

Measures

Social anxiety screens

Social anxiety symptoms were measured at baseline using the SPIN and the SOPHS. The SPIN is a 17-item measure in which participants rated on a five-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) the extent to which a symptom affected them over the past week. A score of 19 or above has been shown to accurately identify social phobia caseness with a sensitivity of 72.5% and specificity of 84.3%.15 Accordingly, participants who scored 19 or above on the SPIN were included in the analyses. The internal reliability of the SPIN in this study was 0.85 for the participants who satisfied the inclusion criteria (n = 83).

The SOPHS is a five-item social phobia screen in which participants rated on a five-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) the extent to which a symptom affected them over the past month. Reporting a ‘1’ (a little) or above on items 1, 2 and 5 and either items 3 or 4 has been shown to accurately identify social phobia caseness with a sensitivity of 77.9% and specificity of 71.7%.16 The internal reliability of the SOPHS in this study was 0.81.

Participants were eligible for the study if they met the criteria on either the SPIN or the SOPHS.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was help-seeking intentions measured at baseline and post-intervention using the General Help-seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ).20 Participants were asked to rate on a seven-point scale (1 = extremely unlikely to 7 = extremely likely) the likelihood of seeking help from 12 different sources if feeling shy or socially anxious. Of the 12 sources of help that the Shyness Information Online program reported, among others, four were evidence-based sources for SAnD: psychologist, psychiatrist, general practitioner (GP), and Internet (an online cognitive behavioural program). A professional GHSQ scale was computed from three items (psychologist, psychiatrist and GP) but the Internet item was not included as it could not be determined whether respondents were referring to a credible source. All remaining items including ‘I would not seek help from anyone’ were analysed individually. Higher scores indicated greater help-seeking intentions. The internal reliability in this study for the professional GHSQ at baseline was 0.87. The test-retest reliability in the control group for this measure was 0.84.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures were help-seeking attitudes, internalised social anxiety stigma, social anxiety literacy and a perceived need for treatment.

Participants’ attitudes toward help seeking were measured at baseline and post-intervention using an abridged (three-item) version of the Attitudes Towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form (ATSPPH-SF).21 Participants indicated the extent of their agreement with each of three statements on a four-point scale (0 = disagree to 3 = agree). Higher scores indicated a more positive attitude towards seeking professional psychological help. The internal reliability in this study for the help-seeking attitudes scale at baseline was only 0.65. However, the corrected item-total correlation exceeded 0.3 for each item, which is acceptable for such a brief measure. The test-retest reliability for the control group for this measure was 0.83.

Social anxiety literacy was measured at baseline and post-intervention using a purpose-developed measure (see Table 2 for full list of items), the Social Anxiety Literacy Questionnaire (SA-Lit). The SA-Lit aimed to measure respondents’ knowledge about the causes, symptoms, and treatment of social anxiety. It comprised 12 items each consisting of a statement to which the participant was asked to respond ‘true’ or ‘false’. Participants received no feedback on the accuracy of their responses. The overall score was the number of correct items, with higher scores indicating greater social anxiety literacy. The test-retest reliability in the control group for this measure was 0.85.

Table 2.

Social anxiety literacy questionnaire items.

| 1. | Social anxiety is uncommon. (False) |

| 2. | There are effective psychology (talk) treatments for social anxiety. (True) |

| 3. | Some people are born with a tendency to see the world around them as threatening. (True) |

| 4. | A person’s thoughts about social situations can affect their social anxiety. (True) |

| 5. | It’s best to cope with social anxiety by avoiding social situations. (False) |

| 6. | People who are shy or socially anxious don’t want to relate to other people. (False) |

| 7. | There are no effective mediations for social anxiety disorder. (False) |

| 8. | Antidepressants are no help for social anxiety disorder. (False) |

| 9. | Antidepressants are addictive. (False) |

| 10. | Beta blockers may help people who are anxious about performing in front of others. (True) |

| 11. | The best way of dealing with a social anxiety disorder is to handle it yourself. (False) |

| 12. | Social anxiety disorder can disrupt a person’s life as much as depression. (True) |

Internalised social anxiety stigma was measured at baseline and post-intervention using the Social Anxiety Stigma Scale (SASS-I). Based on items in the personal subscale of the Generalised Anxiety Stigma Scale,22 but further modified to assess the participant’s view of their own social anxiety, this measure required participants to rate the extent of their agreement with eight statements on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicated higher levels of internalised social anxiety stigma. The internal reliability in this study for SASS-I at baseline was 0.76. The test-retest reliability in the control group for this measure was 0.76.

Perceived need for treatment was measured using the single yes/no item at baseline and post-intervention: ‘Do you see any need for treatment of your shyness or social anxiety?’.

Subsidiary measures

At post-intervention, participants in the Shyness Information Online group rated their satisfaction with the program content, acceptability of the program, and the perceived amount learned about SAnD. In addition, the participants were asked ‘Would you like access to an online program for SAnD?’. Although those who indicated their interest were provided with a link to the evidence-based online cognitive behavioural program at the completion of the SAnD survey, budgetary limitations precluded the establishment of trial mechanisms to record the number of participants who accessed the program.

Planned sample size

As this was a pilot trial our intention was not to undertake a fully powered trial but rather to generate data that would inform the design of such a trial in the future. Accordingly, the planned sample size for this pilot trial was 40 (20 per group), this number being based on time and budget constraints.

Analyses

Consistent with the a priori protocol recorded on the trials register, the main primary and secondary outcome analyses were undertaken on participants who satisfied caseness on the SPIN and separate additional analysis was undertaken on participants who satisfied caseness on the SOPHS.

Continuous outcome data were analysed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., 2013). These data were examined using mixed-model repeated-measures analysis (MMRM), assuming an unstructured covariance matrix with degrees of freedom estimated using Satterthwaite’s correction. Dichotomous and ordinal outcome data were analysed using Stata v14 (StataCorp, 2015). These outcomes were analysed using a random-intercept binary logistic regression or a generalised linear latent and mixed models (GLLAMM) procedure. A random-participant-intercept model with adaptive quadrature was specified. Analyses were conducted on an intent-to-treat (ITT) basis using all available data under the missing at random assumption.

Since the rates of attrition were elevated, we also undertook a sensitivity analysis in the form of a completer analysis. The completer analyses used identical methods to the ITT analysis (MMRM and GLLAMM), but only participants who had completed the primary outcome measure, professional GHSQ at all time points, were included in these analyses. Although this approach is more open to bias than the ITT analysis, the purpose of it was to examine whether an alternative analytic approach provided consistent findings.

Due to the small number of participants, effect sizes were calculated based on Hedges’ g and an adjusted effect size was computed by subtracting the between-group baseline Hedges’ g from the between-group post-intervention Hedges’ g.23 Only the adjusted Hedges’ g values are reported.

Between group comparisons of baseline demographic and study measures, and post-intervention attrition were undertaken using an independent samples t-test for continuous data, or chi-square tests for categorical data.

Results

Participant recruitment

A total of 2862 Facebook users clicked on the research advertisement. Overall the majority of website clicks were from users who registered their Facebook profile details as being female, and aged 55 years or older. The greatest number of consenters registered on an Australian national holiday (Monday 26 January 2015).

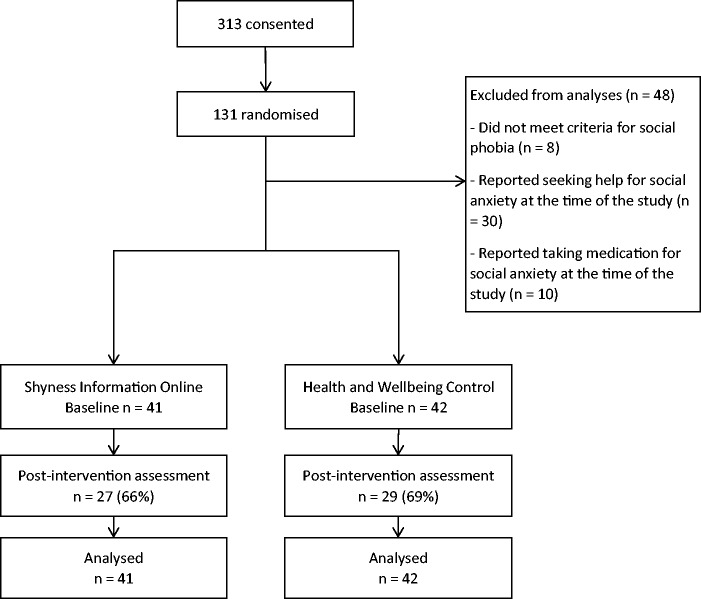

Participant flow

A Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram of participant flow is shown in Figure 1. A total of 313 people consented to participate in the study, of whom 131 completed all baseline measures and were randomised into the trial. After excluding 48 participants (26 intervention and 24 control), who did not satisfy the inclusion criteria for the current analyses, the sample comprised 83 participants.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants.

Baseline characteristics

Table 3 presents the baseline demographic and study measures as a function of group. Overall, the majority of the participants were women (91.5%), in a relationship (51.2%), tertiary educated (52.4%) and employed either full or part-time (64.6%). The average age of participants was 44 years (standard deviation (SD) = 15 years). Based on their SPIN scores, participants on average had a severe level of social anxiety at baseline (mean = 41.0, SD = 10.0). At baseline, a greater percentage of control than intervention participants were in a relationship, employed either full or part-time and resided in rural areas (see Table 3). No other differences were observed.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of participants (Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) ≥ 19) by group and statistical comparisons.

| Shyness n = 41 | Control n = 41 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | Statistical comparison | ||

| Gender | Female | 38 (92.7) | 37 (90.2) | χ2(1, n = 82) = 0.16, p = 0.69 |

| Relationship status | Married/de facto | 14 (34.1) | 28 (68.3) | χ2(1, n = 82) = 9.6, p = 0.002 |

| Education | Tertiary educated | 23 (56.1) | 20 (48.8) | χ2(1, n = 82) = 0.44, p = 0.51 |

| Employment | Employed full or part-time | 22 (53.7) | 31 (75.6) | χ2(1, n = 82) = 4.3, p = 0.04 |

| Residence | Rural | 32 (22.0) | 23 (43.9) | χ2(1, n = 81) = 3.9, p = 0.05 |

| Perceived need for treatment | Yes | 22 (53.7) | 19 (46.3) | χ2(1, n = 82) = 0.44, p = 0.51 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age (years) | 42.0 (15.6) | 45.6 (14.9) | t(80) = 1.1, p = 0.28 | |

| SPIN | 39.6 (8.7) | 42.3 (11.1) | t(80) = 1.2, p = 0.23 | |

| Professional GHSQ | 8.1 (5.4) | 6.5 (4.9) | t(80) = 1.5, p = 0.15 | |

| Attitudes | 5.5 (2.5) | 4.9 (2.5) | t(80) = 1.2, p = 0.25 | |

| Literacy | 8.7 (2.0) | 8.2 (2.4) | t(80) = 0.86, p = 0.40 | |

| Stigma | 22.0 (5.6) | 22.4 (6.0) | t(80) = 0.33, p = 0.75 |

GHSQ: General Help-seeking Questionnaire; SD: standard deviation.

Attrition across conditions and characteristics of non-completers

At post-intervention 26 participants did not complete the professional GHSQ (intervention n = 14 and control n = 12). There were no statistically significant differences in the baseline characteristics of completers and non-completers.

Intervention effectiveness: outcomes for the SPIN cases

The main analyses were undertaken on the outcomes for the 82 participants who scored 19 or above on the SPIN. The presence of a statistically significant interaction between group and time, indicated a differential effect of the intervention relative to the control group on the outcome measure. Table 4 summarises the results for each outcome measure.

Table 4.

Estimated marginal means (EMMs) and standard errors (SEs) for each group and measurement point and group × time interactions from the intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses.

| Measure | Group | Baseline EMM (SE) | Post-intervention EMM (SE) | Group × time interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional GHSQ | Shyness | 8.1 (0.80) | 9.4 (0.89) | F(1,56.2) = 2.86, p = 0.097 |

| Control | 6.5 (0.80) | 6.3 (0.87) | ||

| Help-seeking attitudes | Shyness | 5.5 (0.39) | 6.4 (0.39) | F(1,59.4) = 5.25, p = 0.025 |

| Control | 4.9 (0.39) | 4.8 (0.38) | ||

| Literacy | Shyness | 8.7 (0.34) | 10.5 (0.34) | F(1,58.7) = 14.94, p ≤ 0.001 |

| Control | 8.2 (0.34) | 8.7 (0.34) | ||

| Stigma | Shyness | 22.0 (0.90) | 19.5 (1.1) | F(1,50.7) = 1.47, p = 0.231 |

| Control | 22.4 (0.90) | 21.3 (1.1) | ||

| Yes n a (%) | Yes n a (%) | |||

| Perceived need for treatment | Shyness | 22 (53.7) | 21 (51.2) | z = 3.77, p < 0.001 |

| Control | 19 (46.3) | 13 (31.7) |

GHSQ: General Help-seeking Questionnaire.

Raw n (%) (% calculated from the total number of participants at baseline – 41 intervention, 41 control).

Help-seeking intentions (GHSQ)

Although there was a significant group effect in favour of greater intentions to seek help among the intervention group (F(1,80.3) = 4.5, p = 0.036, adjusted hedges’ g = 0.26), the interaction between group and time for professional help-seeking intentions did not attain statistical significance (p = 0.097). Nor were there any significant interaction effects between group and time for the individual help-seeking intention items (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Results from generalised linear latent and mixed models (GLLAMM) analyses of individual General Help-seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ) item sources of help for participants who reported ≥19 on the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN).

| Item | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partner | 0.91 (1.0) | −1.1–2.9 | 0.89 | 0.37 |

| Friend | 1.5 (0.92) | −0.29–3.3 | 1.6 | 0.10 |

| Mother | 1.3 (1.3) | −1.2–3.7 | 1.0 | 0.31 |

| Father | −0.63 (1.6) | −3.8–2.6 | −0.39 | 0.70 |

| Other relative/ family member | 0.64 (0.94) | −1.2–2.5 | 0.68 | 0.50 |

| Psychologist | 1.0 (0.89) | −0.74–2.8 | 1.1 | 0.26 |

| Psychiatrist | 1.6 (0.99) | −0.37–3.5 | 1.6 | 0.11 |

| GP | 1.4 (0.91) | −0.38–3.2 | 1.5 | 0.12 |

| Phone help line | −0.31 (1.1) | −2.4–1.8 | −0.29 | 0.78 |

| The Internet | 1.4 (0.79) | −0.16–3.0 | 1.8 | 0.08 |

| Work colleague | 1.2 (1.2) | −1.2–3.5 | 1.0 | 0.33 |

| Priest/minister | 4.4 (2.5) | −0.52–9.4 | 1.8 | 0.08 |

| I would not seek help from anyone | −0.24 (0.79) | −1.8–1.3 | −0.31 | 0.76 |

CI: confidence interval; GP: general practitioner; SE: standard error.

Help-seeking attitudes (ATSPPH-SF)

There was a significant interaction between group and time for help-seeking attitudes, with the intervention group displaying a greater increase in positive attitudes toward professional help than the control group from baseline to post-intervention (p = 0.03, adjusted Hedges’ g = 0.38).

Literacy (SA-Lit)

There was a significant interaction between group and time for knowledge of social anxiety, with participants in the intervention group reporting, on average, a greater increase in correct items on the anxiety literacy scale than the control group from baseline to post-intervention (p ≤ 0.001, adjusted Hedges’ g = 0.46).

Internalised stigma (SASS-I)

There was no significant interaction between group and time for internalised social anxiety stigma (p = 0.23, adjusted Hedges’ g = –0.23). However, a main effect for time indicated that both the intervention and control group showed less internalised stigma at post-intervention than at baseline (F(1,50.7) = 1.5, p = 0.002).

Perceived need for treatment

There was a significant interaction between group and time for the perceived need for treatment (Wald Chi-square = 23.3, z = 3.8, p ≤ 0.001). Specifically, between baseline and post-test there was a greater change in the proportion of participants perceiving a need for treatment for the intervention group than the attention control condition (ß = 10.8).

Recruitment feasibility, satisfaction and acceptability of the intervention and control

The sample of 83 eligible participants was recruited over 11 days via Facebook. Overall 26 participants in the shyness group provided data on the post-intervention satisfaction items. A majority of the respondents (n = 22, 84.6%) were either very satisfied or satisfied with the content of the Shyness Information Online website; only one (3.8%) expressed dissatisfaction. All but one respondent found the program content helpful (96.2%), and 22 (84.6%) indicated that they would recommend the site to others. A majority agreed that the website helped them to: learn more about shyness (n = 22, 84.6%), learn more about the treatments available for social anxiety (n = 19, 73.1%) and understand the need to seek help for their shyness (n = 19, 73.1%). A total of 18 (69.2%) respondents indicated a desire to access the online treatment tool for social anxiety that was described in the intervention program.

There was also a high level of satisfaction with the control website. Of the 26 control participants who provided satisfaction data, 20 (76.9%) were satisfied or very satisfied with the content of the website, 25 (96.2%) found it helpful, and 22 (84.6%) would recommend the site to others. There was no statistical difference in satisfaction between the shyness and control websites (satisfaction: χ2(1, 52) = 0.5.9, p = 0.20; helpful: χ2(1,46) = 0.70, p = 0.40; recommend to others: χ2(1,52) = 1.0, p = 0.31).

Covariate-adjusted analyses

To take into account significant baseline differences between the groups on two measures, the analyses were re-run to include the covariates in the model. Covariates were entered into the model as a fixed main effect. Compared to the unadjusted results, the covariate-adjusted analyses revealed little change in the p-values, with no change to the conclusions of hypothesis testing.

Sensitivity (completer) analyses

The results of the completer analyses supported those of the ITT results. A significant interaction between group and time was found for professional help-seeking attitudes (p = 0.049), literacy (p < 0.001) and perceived need for treatment (p < 0.009). No significant interaction was found for internalised stigma (p = 0.27) or professional help-seeking intentions although the latter effect approached significance (p = 0.06).

Intervention effectiveness: outcomes for the SOPHS cases

The SOPHS cutoff criterion was more stringent than the SPIN cutoff. With one exception, participants meeting the SOPHS criterion also met the SPIN cutoff whereas 10 participants met only the SPIN criterion. Accordingly the sample of participants who met diagnostic criteria for social phobia on the SOPHS was smaller than the SPIN sample (73 and 82 respectively). All participants in the SOPHS analyses were included in the above primary analyses, with the exception of one participant. Due to the overlap in samples, participant characteristics and results for the outcome measures were similar, with three exceptions. First, although – as with the SPIN sample – the group by time interaction for professional GHSQ was not statistically significant, the effect approached significance for the group of participants reporting social anxiety on the SOPHS (F(1,49.5) = 3.8, p = 0.06) (adjusted Hedges’ g = 0.30). Second, the result for the Internet help-seeking intention item revealed a significant interaction between group and time, with the intervention group showing a greater increase in intention to seek help from baseline to post-intervention than the control group (z = 2.2, p = 0.03). Third, the interaction between group and time for help-seeking attitudes was not statistically significant. However, this interaction between group and time for professional help-seeking attitudes did attain statistical significance in the completer analysis (p = 0.033). Otherwise the completer analyses yielded similar results to the ITT analyses for the SOPHS cases.

Discussion

This study yielded some promising findings. Perhaps not surprisingly given the small sample size, the hypothesised differential improvement in help seeking for the intervention group in the primary outcome – help-seeking intention for SPIN cases – did not attain statistical significance (p = 0.097). However, the effect was in the predicted direction. In addition, the intervention was associated with significantly improved attitudes to help seeking from professionals relative to the attention control. Further, following exposure to the intervention a greater percentage of participants recognised the need for treatment. There was also a trend towards improved intentions to seek help among the participants who satisfied criteria for social anxiety caseness on the SOPHS (p = 0.06), an effect which was significant for SOPH case completers; SOPHS cases also showed a greater increase in intention to seek help from an online source than the control. Consistent with expectations, the intervention was associated with increased knowledge of social anxiety relative to the attention control indicating that in the short term the online program was effective in increasing social anxiety literacy. Contrary to expectation the intervention was not associated with a differential reduction in internalised stigma; rather internalised stigma decreased from baseline to post-intervention in both conditions. Overall, Facebook proved an effective and rapid method for recruitment of people with social anxiety and the intervention was considered satisfactory by those who were assigned to it.

To our knowledge the current study is the first to investigate the effect of an online program on help-seeking-related outcomes for SAnD and thus to demonstrate that exposure to an online SAnD educational program can improve attitudes to, and perceived need for, help seeking for SAnD. The previous small pilot study of intensive face-to-face MET noted earlier11 found that a face-to-face intervention resulted in greater willingness and openness to seeking help among university students but the intervention – which required three face-to-face sessions – has limited scalability and by its nature may have excluded people with avoidance behaviours associated with SAnD. Although there have been no previous studies on online SAnD educational delivery, several such trials have been undertaken for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD).12,24,25 Consistent with the current findings for SAnD, each of the GAD trials reported a greater improvement in attitudes toward seeking professional help amongst those in the intervention than in the control condition.

Since the current pilot study was undertaken in one session only, it was not possible to assess actual help-seeking behaviour. However, previous research has shown that, in people with an anxiety disorder, a higher perceived need for service use was associated with a greater likelihood of accessing mental health services.26 Prospective research has also shown that a perceived need for treatment and positive attitude toward seeking psychological help predicted subsequent service use in the following six months.27 Thus, the current findings demonstrating effects on both perceived need and help-seeking attitudes are promising.

Overall, the encouraging findings from this trial suggest that a fully powered trial is warranted to further investigate the effectiveness of the intervention developed according to the framework, outlined by Griffiths,9 for promoting help seeking for SAnD. Based on the current findings, such a trial should be powered to detect a small effect size (0.25) if the primary outcome is help-seeking intention. In a population context, even small effects have the potential to make a large public health impact when delivered en masse via the Internet.

Intervention participants in the present study demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in SAnD literacy than the control participants. Although, to our knowledge, this is the first study to report such an effect, similar outcomes have been reported for online educational programs targeting other mental disorders including GAD.12,24,25 Since there is prospective evidence that baseline mental health literacy predicts subsequent service use27 the current findings are encouraging. To date, by contrast with other conditions such as depression, SAnD has not been a target of awareness campaigns. The current results could inform such campaigns in the future.

The theoretical help-seeking framework postulates that stigma is a barrier to help seeking and that reducing such stigma may increase help seeking. However, there was no statistically significant effect of the SAnD intervention on internalised SAnD stigma in the current trial. Nevertheless, the magnitude of the effect size (adjusted g = 0.23) was comparable to the pooled effect reported in a recent meta-analysis of 19 studies that examined the effectiveness of stigma reduction interventions in people with mental ill-health (d = 0.28 respectively).28 However, the latter studies measured personal stigma (participant attitude to a mental illness e.g. ‘People with depression should be able to snap out of it’) whereas the current study employed a measure of internalised stigma which was designed to indicate their views about their own social anxiety (‘I should be able to snap out of my shyness or social anxiety’). Further research in the form of a suitably powered trial is required to establish if the Shyness Information Online program or similar intervention is an effective tool for reducing self-stigmatising attitudes in people experiencing SAnD.

The recruitment strategy employing Facebook advertising yielded a greater than anticipated response within the allocated time frame. The exercise demonstrated the feasibility of rapidly recruiting a large number of participants with social anxiety symptoms who were not receiving treatment. Based on the current trial which demonstrated that 80 eligible participants could be recruited in 14 days, this rapid rate of recruitment suggests that it is feasible to use Facebook to attract sufficient participants for a fully powered trial over a relatively short period (but see Limitations below).

A majority of the respondents appeared to be satisfied with the content of the program, would recommend the program to others, and expressed an interest in accessing the online treatment program mentioned in the intervention. The interest in online treatment coupled with the increased intentions to seek help from the Internet indicated that the online delivery of the program may serve as a seamless transition from promoting help seeking to actual help, as predicted.

Limitations and future research

The current study had a number of limitations. In particular it employed a small sample size and did not include a follow-up assessment or an objective behavioural outcome measure of help seeking. It provides an estimate of the effect size required for a fully powered study to investigate help-seeking intentions but does not provide comparable data for help-seeking behaviour. Thus, this trial does not provide a definitive or comprehensive test of the proposed help-seeking behaviour framework. We could not, for example, test if the increase in SAnD knowledge, attitudes toward professional help seeking, and perceived need for treatment mediated a relationship between help-seeking intentions and behaviour. A large-scale trial of the intervention is required to explore these questions and to examine the program’s effectiveness. The protocol for this trial should incorporate a behavioural help-seeking outcome measure and an extended follow-up period, and be powered to detect an effect size somewhat lower than 0.26 given that the effect size for help-seeking behaviour may be lower than that for help-seeking intentions. The inclusion of additional scales may prove useful to better predict help-seeking intentions and behaviour. For example, consistent with the positive results obtained by Buckner and Schimdt,11 there may be value in including measures of openness and willingness to seek help. There may also be value in incorporating measures of motivation including a measure of ambivalence about treatment. There was no difference in the participant satisfaction ratings for the shyness and wellbeing websites, suggesting that the control condition was a credible intervention. Further, the participants were not informed of the true aim of the study to minimise potential performance bias. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that some participants may have deduced the objective of the study from the survey items and that this may have influenced the results.

Another limitation of the study was that the majority of participants were women. Therefore the applicability of the intervention to men is unknown. Although most studies have demonstrated that the rate of SAnD in the community is higher among women than among men29 and women are more likely to seek out health information than men,30 the magnitude of this differential prevalence is not sufficient to account for the very high level of women entering the trial. Moreover, the percentages of men and women who join Facebook are broadly similar31 and some previous trials that have focused on mental disorders and employing Facebook as a recruitment method have attracted a greater percentage of male participants than the current study.32 Thus, the reason for the low recruitment level for men is unclear. Given the importance of increasing help seeking among men, there is a need to explore methods for increasing recruitment male rates in a full-scale trial of the shyness intervention. It is possible, for example, that men do not respond well to the enquiry ‘Are you shy?’. If this is the case, rephrasing the advertisement to employ an alternative descriptor might yield a greater percentage of male recruits. However, there is a need to undertake empirical testing to test the veracity of this hypothesis and to identify the most suitable phrasing for a Facebook advertisement designed to attract men with SAnD.

A final limitation relates to the level of attrition in the study. Although a sensitivity analysis in the form of a completers study yielded similar results to the ITT approach, it is possible that the findings from both analyses were biased towards positive outcomes. There are several means by which a fully funded trial might overcome these limitations. First, the intervention for such a trial could be upgraded to include attractive graphical and multi-media elements designed to increase participant engagement. Secondly, whereas participants in the current trial were anonymous, those in a prospective study will be identifiable. As a result participants may feel a greater sense of accountability for their participation, and their participation can be tracked and reminders delivered to complete tasks. Ideally a full-scale prospective study will distribute the administration of the pre- and post-surveys and the intervention delivery across separate sessions. We acknowledge that a requirement to participate across multiple sessions might increase attrition. However, it is likely that any such effect would be offset by the reduction in demands associated with completing all tasks in a single session.

Conclusions

This pilot study was the first to trial an intervention derived from a help-seeking behaviour framework which aimed to promote help-seeking behaviour in individuals experiencing SAnD. The results from the trial showed some evidence for the utility of the Shyness Information Online intervention, including an improvement in help-seeking attitudes and a perceived need for treatment, knowledge, and beliefs. A fully powered trial with recruitment via Facebook is feasible, and is required to provide a more rigorous test of these preliminary findings and to examine the effect of the intervention on help-seeking behaviour. A large sample with extended follow-up would also allow for exploration of the relationships between the factors that influence help-seeking behaviour. Finally, further testing of the model has the potential to identify the program components that may benefit from expansion and to identify less effective components that could be altered or removed. SAnD is a much neglected condition.9 If shown effective, the present intervention – or others based on the help-seeking framework which informed it9 – have the potential to decrease the individual and public burden associated with this debilitating condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anthony Bennett, Kylie Bennett and Ada Tam for their role in implementing the Shyness Information Online program. The authors also appreciate the expert advice provided by Julia Reynolds and Britt Klein.

Contributorship

KG conceived and designed the study. Both the online intervention and attention control programs were scripted by KG. JW and KG drafted the paper. JW implemented and coordinated the trial and undertook the statistical analyses. PB provided detailed statistical advice and supervisory oversight. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the paper.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

The protocol for the study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at The Australian National University (protocol number 2014/739).

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: At the time of the study KG was supported by a National Health & Medical Research Fellowship (No. 1059620) and PB was supported by National Health & Medical Research Fellowship (No. 1083311).

Guarantor

KG.

Peer review

This manuscript was reviewed by two individuals who have chosen to remain anonymous.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al. Disability and quality of life impact of mental disorders in Europe: Results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004; 109: 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filho AS, Hetem L, Ferrari M, et al. Social anxiety disorder: What are we losing with the current diagnostic criteria? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010; 121: 216–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ormel J, Petukhova M, Chatterji S, et al. Disability and treatment of specific mental and physical disorders across the world. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 192: 368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Chelminski I, et al. Diagnostic co-morbidity in 2300 psychiatric out-patients presenting for treatment evaluated with a semi-structured diagnostic interview. Psychol Med 2008; 38: 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiller E, Bisserbe J, Boyer P, et al. Social phobia in general health care: An unrecognised undertreated disabling disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168: 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayo-Wilson E, Dias S, Mavranezouli I, et al. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2014; 1: 368–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffiths KM. Towards a framework for increasing help-seeking for social anxiety disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2013; 47: 899–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews GG, Issakidis C, Sanderson K, et al. Utilising survey data to inform public policy: Comparison of the cost-effectiveness of treatment of ten mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184: 526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckner JD, Schmidt NB. A randomized pilot study of motivation enhancement therapy to increase utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety. Behav Res Ther 2009; 47: 710–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, et al. Internet-based interventions to promote mental health help-seeking in elite athletes: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2012; 14: e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chartier-Otis M, Perreault M, Bélanger C. Determinants of barriers to treatment for anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Q 2010; 81: 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olfson M, Guardino M, Struening E, et al. Barriers to the treatment of social anxiety. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 521–527. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Connor KM, Davidson JRT, Churchill LE, et al. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN). New self-rating scale. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176: 379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batterham PJ, Mackinnon AJ and Christensen H. Community-based validation of the social phobia screener (SOPHS). Assessment. Epub ahead of print 3 March 2016. DOI 10.1177/1073191116636448. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Bowler JO, Mackintosh B, Dunn BD, et al. A comparison of cognitive bias modification for interpretation and computerized cognitive behavior therapy: Effects on anxiety, depression, attentional control, and interpretive bias. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012; 80: 1021–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Australian Government. Make your move – sit less – be active for life! A resource for families. Canberra: Department of Health, 2014.

- 19.US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity guidelines for Americans. Be active, healthy and happy. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008.

- 20.Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi J, et al. Measuring help-seeking intentions: Properties of the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire. Can J Counsell 2005; 39: 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elhai JD, Schweinle W, Anderson SM. Reliability and validity of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form. Psychiatry Res 2008; 159: 320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffiths KM, Batterham PJ, Barney L, et al. The Generalised Anxiety Stigma Scale (GASS): Psychometric properties in a community sample. BMC Psychiatry 2011; 11: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durlak JA. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. J Pediatr Psychol 2009; 34: 917–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor-Rodgers E, Batterham PJ. Evaluation of an online psychoeducation intervention to promote mental health help seeking attitudes and intentions among young adults: Randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2014; 168: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths K, Bennett K, Walker J, et al. Effectiveness of MH-Guru, a brief online mental health program for the workplace: A randomised controlled trial. Internet Interv 2017; 6: 29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Codony M, Alonso J, Almansa J, et al. Perceived need for mental health care and service use among adults in Western Europe: Results of the ESEMeD project. Psychiatric Serv 2009; 60: 1051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Bonabi H, Müller M, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Mental health literacy, attitudes to help seeking, and perceived need as predictors of mental health service use: A longitudinal study. J Nerv Ment Dis 2016; 204: 321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffiths KM, Carron-Arthur B, Parsons A, et al. Effectiveness of programs for reducing the stigma associated with mental disorders. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry 2014; 13: 161–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furmark T, Tillfors M, Everz PO, et al. Phobia in the general population: Prevalence and sociodemographic profile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34: 416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox S. Health topics: 80% Of Internet users look for health information online,http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media//Files/Reports/2011/PIP_Health_Topics.pdf, (February 2011, accessed 10 February 2017).

- 31.Pew Research Center. Social media fact sheet, http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/ (January 2017, accessed 10 February 2017).

- 32.Tait RJ, McKetin R, Kay-Lambkin F, et al. Six-month outcomes of a web-based intervention for users of amphetamine-type stimulants: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]