Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to gather the views of sexual health clinic staff and male clinic users regarding digital sexual health promotion and online trial procedures.

Methods

The Men’s Safer Sex website was offered on tablet computers to men in the waiting rooms of three sexual health clinics, in a feasibility online randomised controlled trial (RCT). Interviews were conducted with 11 men who had participated in the trial and with nine clinic staff, to explore their views of the website and views of the online trial. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, and we conducted a thematic analysis of interviews and of 281 free text comments from the online RCT outcome questionnaires.

Results

Clinic users and staff felt that digital interventions such as the Men’s Safer Sex website are useful, especially if NHS endorsed. Pre-appointment waiting time presents a good opportunity for intervention but clinic users and staff felt that a website should supplement rather than replace face-to-face healthcare. The RCT procedures fitted well around clinical activities, but men did not self-direct to the tablet computers. Staff were more concerned about consent and confidentiality than clinic users, and staff and patients were frustrated by multiple technical problems. The trial outcome questionnaire was thought-provoking and could constitute an intervention in itself. Participants felt that clinics would need to promote a digital intervention and/or offer the site routinely to promote engagement.

Conclusion

Digital interventions could usefully supplement in-person sexual health care, but there are important obstacles in terms of IT access in NHS settings, and in promoting engagement.

Keywords: Condoms, digital health, feasibility, men, process evaluation, qualitative, randomised controlled trial, safe sex, sexual health

Background

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a major public health problem, with high social and economic costs.1 Condoms are effective for the prevention of STIs but there are multiple barriers to successful use, and efforts are needed to target the obstacles to condom use that men face.2

Guidance from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that people at high risk of STI are offered one-to-one structured discussions to address risk-taking,1 and interventions such as motivational interviewing are increasingly being offered as part of routine care in sexual health clinics and other health care settings. While behavioural interventions can impact positively on sexual behaviour,1 in practice it is resource intensive to train and support staff, and difficult to find time for structured discussions in clinical services which are struggling to cope with demand. There are additional barriers to health promotion for men, who are less likely than women to visit health professionals3 and can be reluctant to discuss their health with practitioners, partners or friends.4

An online intervention offers an alternative way to reach men at risk of contracting STIs, and digital interventions are suitable for sexual health promotion because access can be private, anonymous and self-paced.5 Interventions can be targeted at specific groups (e.g. by age, gender or sexuality), and content can be tailored for individuals. Interactive digital interventions (IDIs) can be expensive to develop, but offer the advantages of intervention content fidelity and the potential to reach large audiences with relatively low dissemination costs.6

IDIs are defined as ‘Computer-based programmes that provide information and support (decisional, emotional and/or behaviour change support) for health issues’.7 IDIs require contributions from users which alter pathways in the program, to produce personally relevant tailored material and feedback.8 IDIs are effective for conveying sexual health knowledge, and can also have an impact on sexual behaviour (including condom use),7,9,10 but there are few interventions for men who have sex with women, and more evidence is needed to establish effects on biological outcomes (STIs) and cost effectiveness.

The Men’s Safer Sex website was developed in collaboration with male clinic users and offered tailored advice to men while they were in the waiting rooms of sexual health clinics. The website is an IDI which aims to increase condom use and reduce STI in men who have sex with women. The Men’s Safer Sex website incorporates behaviour change techniques and provides personalised feedback on barriers to condom use.11,12 The website targets a number of influences on effective condom use including condom knowledge (e.g. about sizes and types of condoms); condom use skills; difficulties in negotiating condom use; inaccurate beliefs about STI risk; social influences, such as perceived/expected partner response; sexual pleasure; and alcohol and drug use.

We opted for an online trial to evaluate the Men’s Safer Sex intervention website.13 Conducting trials online has a number of advantages when compared with more traditional trial methods,14 including the ability to recruit large numbers of participants in a relatively short period of time at lower cost; recruitment of some hard-to-reach groups; automated randomisation and data collection; automated follow-up reminders; reduced burden on participants; and increased participant anonymity, which may be particularly important when providing information about sexual health. While there are many advantages to using online methodologies for randomised controlled trials (RCTs), online trials can be associated with a number of problems, including poor engagement with interventions, and poor retention at follow-up.15

There is policy support in England to develop and implement digital health interventions16 and there has been rapid but localised innovation in this area.17 However, most commercially developed digital interventions have been developed without rigorous evaluation, so their effectiveness and potential adverse effects are not known. There are also challenges to conducting trials in NHS settings, such as competing clinical and research priorities for clinic staff, and lack of appropriate space for research activity. In sexual health research, it may be difficult to recruit people who may have a short-term curable condition (as opposed to a chronic condition), and it can be hard to engage and retain men in research. It is important to determine the best ways of evaluating digital interventions, to allow rigorous evaluation before implementation.6

We conducted a feasibility RCT in three sexual health clinics, recruiting men who have sex with women and randomising them to either the intervention website plus usual clinic care, or usual care only (see Box 1).13 Men were successfully recruited from sexual health clinic waiting rooms, and clinical records were located for 94% of participants. However, a third of the intervention group did not see the Men’s Safer Sex website (n = 31/84), and response rates for follow-up online questionnaires were poor (36% at 3 months (57/159), and 50% at 12 months (79/159)). New acute STI diagnoses were recorded for 8.8% (7/80) of the intervention group, and 13.0% (9/69) of the control group over 12 months (IRR = 0.75, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.90).13 This paper is a qualitative evaluation which reports male clinic users’ and staff experiences and views of the Men’s Safer Sex online trial, and their views on the potential for delivering digital interventions for sexual health in NHS clinic settings.

Box 1.

Summary of the Men’s Safer Sex feasibility RCT.

| Design: the feasibility RCT tested the Men’s Safer Sex, interactive website plus usual clinical care in comparison with usual clinical care only. The study was designed to evaluate retention rates, methods of contact with participants, and methods of sexual health outcome measurement. |

| Recruitment: posters were placed in three sexual health clinics and leaflets handed out by reception staff, inviting male sexual health clinic attendees to register for the study on a tablet computer in the clinic waiting room. |

| Eligibility: men aged 16 and over, sexually active with female partners, able to read English, active email account and access to the Internet, not receiving care for a blood-borne infections (HIV, hepatitis and /or syphilis), and at risk of future STI (i.e. unprotected sex in the previous 3 months AND two or more partners in the last year). |

| Online enrolment and consent: eligibility for the trial was established with questions presented on the tablet computer. After providing consent online, participants created a username and password and were directed to a baseline demographic and sexual health questionnaire. |

| 176 participants consented to participate in the trial. After removal of duplicate or invalid registrations, 159 people participated in the online trial. |

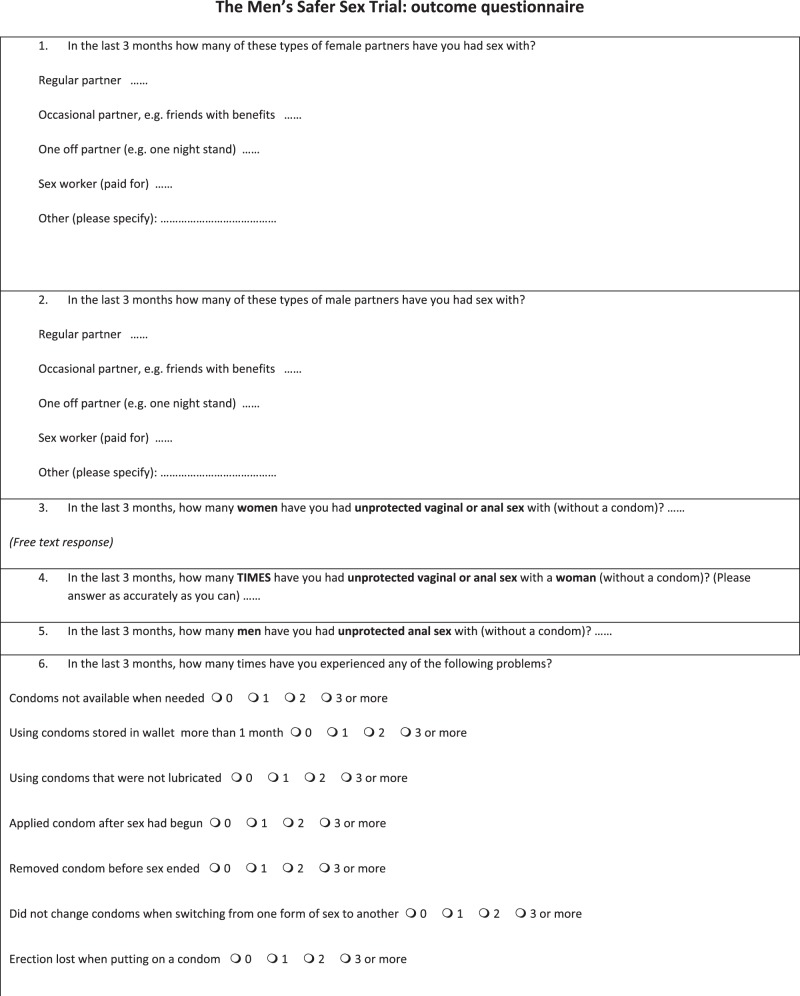

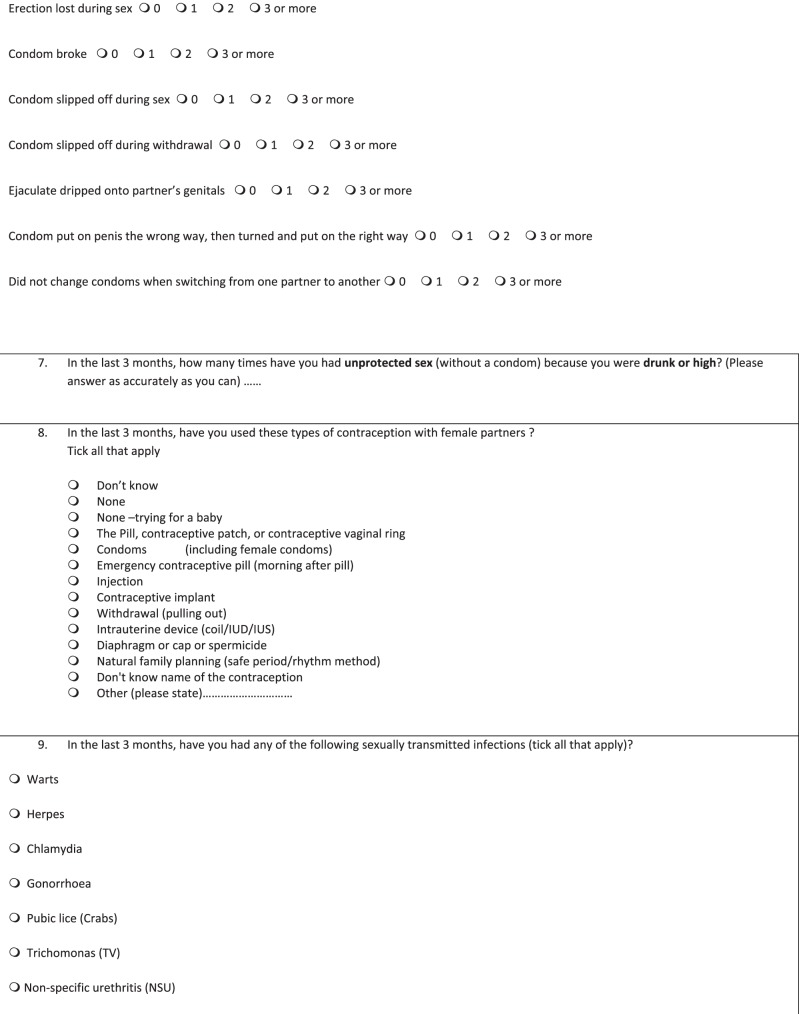

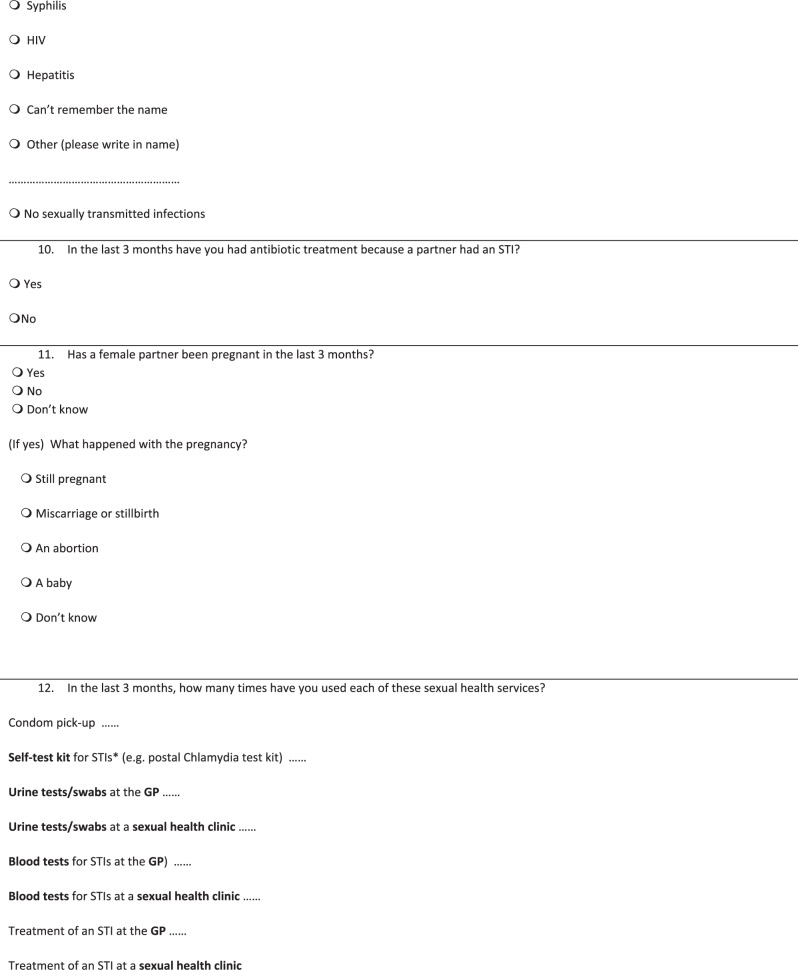

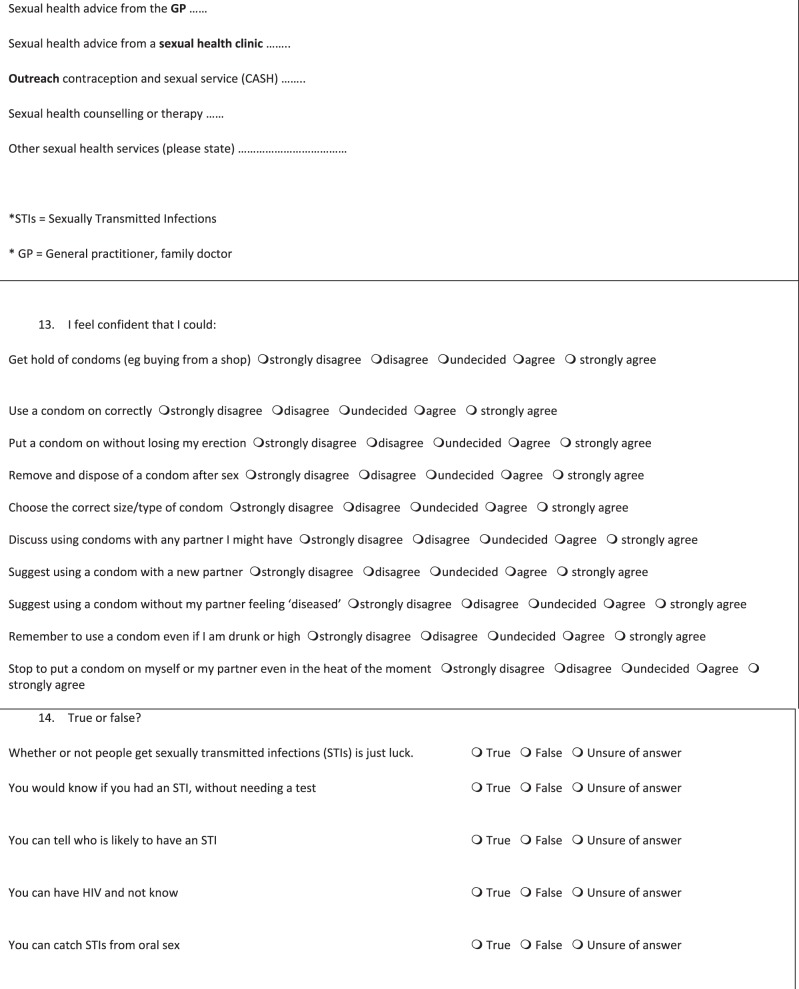

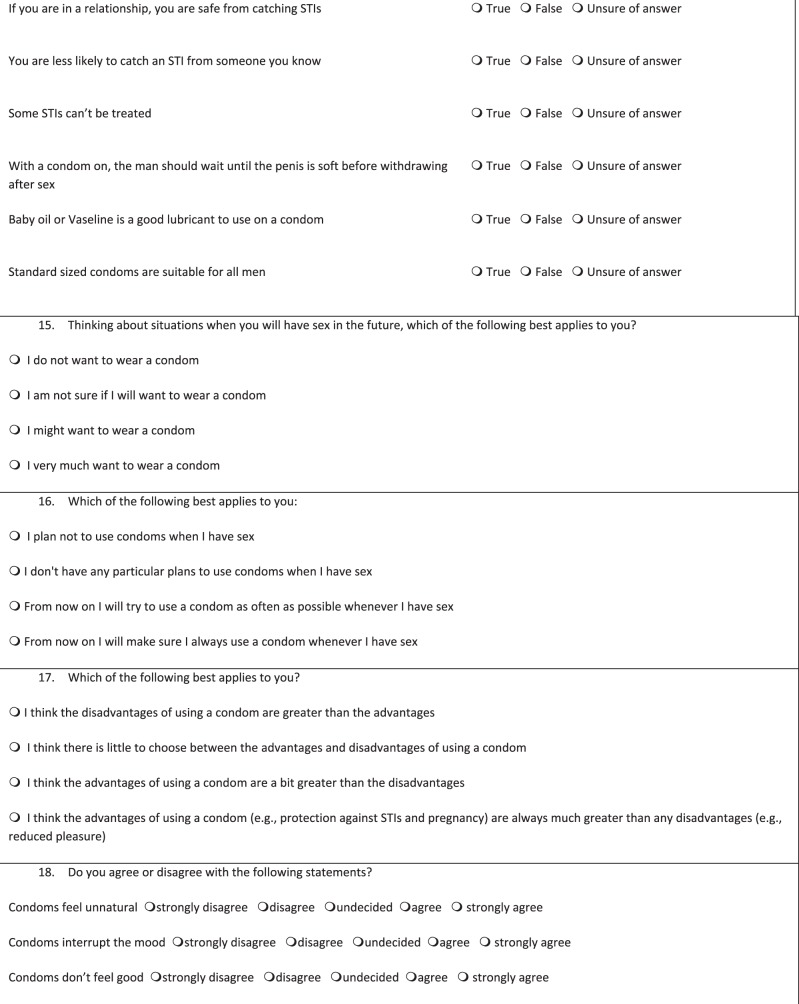

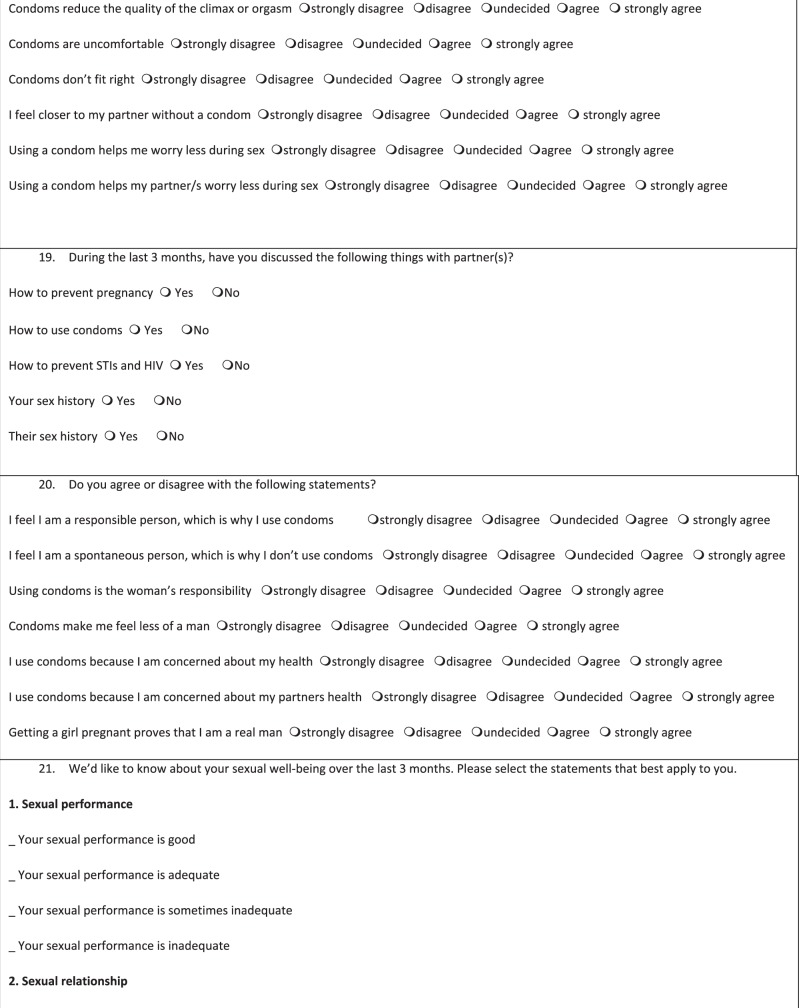

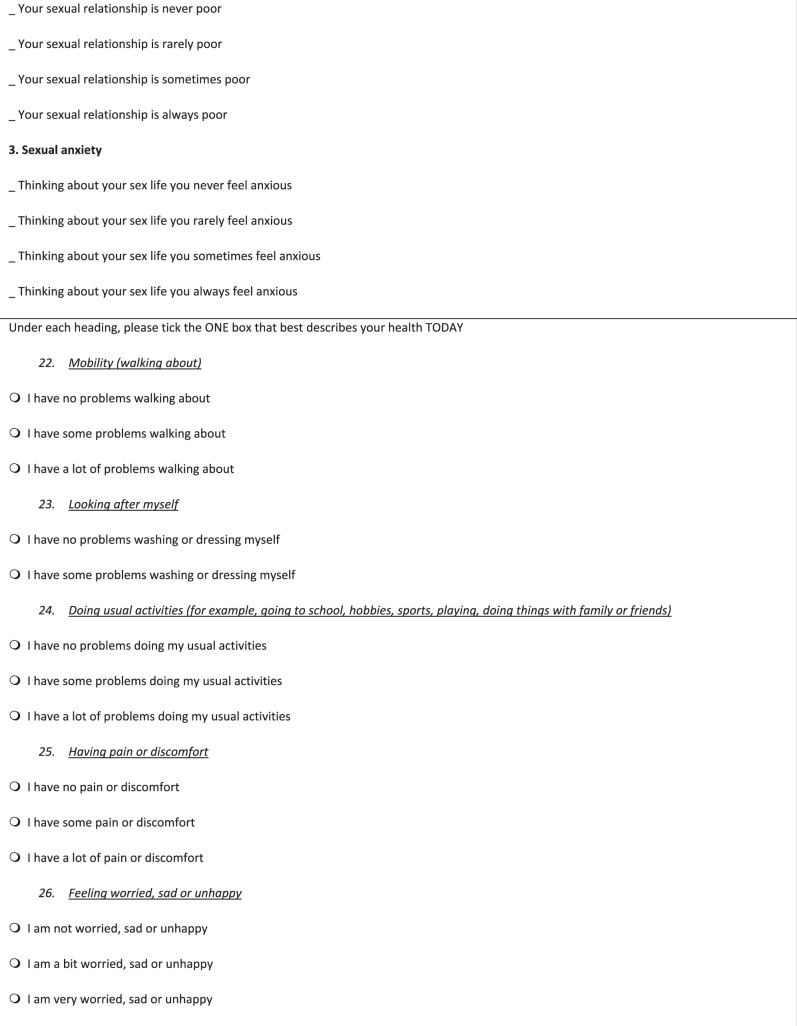

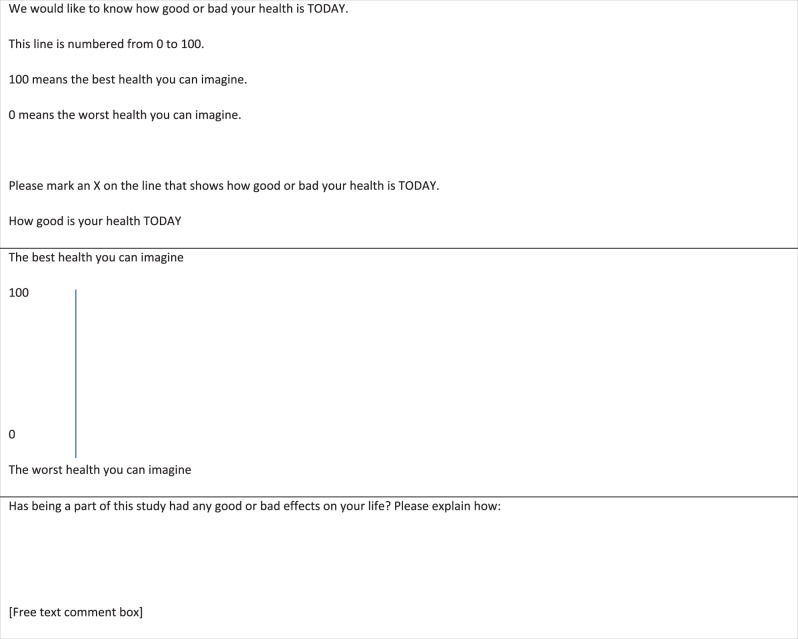

| Baseline data: demographic and contact information including email address and telephone number was collected online at the start of the project. Participants also completed a sexual health questionnaire (Appendix 1). |

| Randomisation: after completing the baseline questionnaire, 84 participants were randomised to the Men’s Safer Sex website and 75 to the comparator (usual care only). The intervention group was given unlimited access to the intervention website during the course of the study. |

| Follow-up: participants were contacted by email at 3, 6 and 12 months and invited to click on a hyperlink to complete the follow-up sexual health questionnaire, which measured mediators of behaviour change (beliefs about pleasure, motivation, knowledge, self-efficacy), behavioural outcomes (including condom use, STI testing, communication with partner/s) and self-reported STI incidence. The main outcome of interest was number of episodes of unprotected sex at 3-month follow-up. Service use and quality of life were measured for a cost-effectiveness analysis. Non-responders were contacted by telephone. A total of £50 in online shopping vouchers was offered for self-reported follow-up data. STI diagnoses were recorded from clinic records at 12 months. |

| Trial registration number: ISRCTN18649610 |

| Ethical approval was provided by the City and East NHS Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13 LO 1801). |

Aims

The aim of this qualitative evaluation was to explore the perspectives of male sexual health clinic attendees and clinic staff on online trial procedures, on the Men’s Safer Sex website, and views on the utility, feasibility and place of digital interventions for sexual health.

Methods

Design

This study was a qualitative evaluation which was conducted in conjunction with a quantitative feasibility RCT. The design of the feasibility RCT of the Men’s Safer Sex website is described in Box 1, and the quantitative outcomes are reported elsewhere.13

Qualitative study design

We used three qualitative data sources to assess the acceptability and validity of the feasibility RCT methodology: (1) individual interviews with 11 RCT participants, recruited at the end of the RCT recruitment period; (2) comments made in free text boxes on the RCT online study outcome questionnaires which were emailed to male participants at 3, 6 and 12 months (281 comments from 46 men) (Appendix 1, trial outcome questionnaire); and (3) individual interviews with nine clinic staff who assisted with the study in three sexual health clinic research sites.

Data source 1: Interviews with male sexual health clinic users

We recruited 48 male study participants in the same way as participants in the Men’s Safer Sex feasibility RCT, on a tablet computer placed in the waiting rooms of sexual health clinics (see Box 1).13 Their experiences of the RCT study procedures were the same, except that email follow-up was at 2 weeks only instead of 3, 6 and 12 months (to enhance recall of trial procedures). An additional question in the online recruitment process asked permission to contact them for a post-study interview. We recruited the qualitative study sample at the end of the trial, and their survey data were not included in the quantitative trial outcome analysis.

We contacted participants by email to arrange times and venues for interviews, and we interviewed 11 out of the 48 sexual health clinic users who had enrolled for the Men’s Safer Sex feasibility trial. We had intended to interview 20 men but researcher sickness prevented this, and as time passed we felt that participants would not be able to adequately recall their experience of being in the online trial. We sampled purposively on the basis of age and trial allocation condition (i.e. intervention or control). These criteria were chosen since age might influence men’s receptiveness to sexual health promotion, and we wished to know about the experience of men allocated to the control group as well as those allocated to the intervention website.

The qualitative interview topic guide included questions regarding methods of recruitment, online registration and consent, the receipt of incentives, the online questionnaires, contact/follow-up via email, and men’s views of the Men’s Safer Sex intervention website (i.e. preference for access point, relevance and usefulness of website, etc.). The interviews were conducted in a variety of settings including sexual health clinic side rooms, university offices and via Skype, by a researcher who had not been involved in the feasibility trial (LH). Participants were offered £20 as a token of appreciation, and an additional £10 if they had also filled in the 2-week online outcome questionnaire. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, with participant permission.

Data source 2: Free text comments on online questionnaires

The feasibility RCT involved filling in baseline and follow-up sexual health surveys (see Box 1). We sought information on potential positive or negative effects of the research itself by offering space for voluntary free text comments after each cluster of questions, and at the end of each online survey. Forty-six of the 159 men in the feasibility trial left comments at the end of at least one of the 3, 6 or 12-month outcome questionnaires (a total of 281 free text comments). Free text comments were collated in an Excel™ file, and coded thematically by adding analytic notes within the Excel software.

Data source 3: Interviews with sexual health clinic staff

All clinic staff members who had been actively involved in the trial conduct at the three clinic research sites were interviewed at the end of the RCT recruitment period (n = 9). Staff were interviewed face to face in clinic rooms by a researcher who had not been involved in the feasibility trial (LH). A topic guide included questions regarding their views on recruitment procedures, and the feasibility and usefulness of providing access to an IDI in a sexual health setting. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, with participant permission.

Analysis of qualitative data

The quality of data collection was reviewed by the research group as the study progressed by listening to audio-recordings of interviews and by discussion of two early transcripts. The topic guide questions were revised in minor ways in the light of this review. Atlas.ti™ software was used to facilitate data retrieval, coding and linkage and to record analytic notes. Thematic analysis was used to identify patterns and links within the data. One researcher (NT) independently coded text from the transcripts, categorised data by theme, and identified relationships between different elements of the text. Coding decisions were reviewed and augmented by a second researcher (JB) and a data analysis meeting with all authors was held to discuss the coding. The coding schema developed for the interview data was used to code the online survey free text comments. The data set was analysed as a whole, seeking consistency or contradiction in themes within the three data sources (men’s views in interviews; men’s free text comments; and clinic staff members’ views), and data were interpreted in the light of the context they were collected.

Findings

Characteristics of participants

Male clinic users

The 11 men who were interviewed varied in age from 19 to 62, with a median age of 27. Eight were sexually active only with female partners; one reported both male and female partners; and two men were sexually active only with male partners. The latter (MSM) had been recruited unintentionally as a result of a software coding error: their interview data were analysed separately; however, their viewpoints on the trial conduct and potential of digital interventions were relevant and have contributed to the qualitative study findings. Most interviewees were white (White British n = 7; White Irish n = 1; White Other n = 2; Black British n = 1). Six interviewees had received the intervention and five were from the control group, and all of the three RCT clinical sites were sampled.

Clinic staff

The nine staff members who were interviewed varied in age from 23 to 65, with a median age of 45. Most interviewees were female (n = 7), with two male staff. Staff were recruited from all three sexual health clinics: four were nurses, two were health advisors, two were clinical studies officers and one was a receptionist. Five of the nine members of staff had a specific research component to their jobs (e.g. research nurse).

Respondents’ views

Men’s reasons for participating in the research

Men commonly cited boredom and a desire to help the researchers out as their main reasons for participating. The promise of a voucher was described by many as an added bonus but most participants said they would have taken part in the online RCT without this incentive. Features of the study which made it more appealing were anonymity, flexibility to fit around patients’ consultations and that it was short. The academic nature of the study and links with the NHS were identified as important motivators for participating.

Men’s understanding of the purpose of the research

Men’s understanding of the research was often incomplete. Many thought it was an exercise in data collection and did not realise that the website was intended as an intervention to change behaviours. However, they were happy to proceed without full understanding. By virtue of its affiliation with a university (University College London) and with the NHS, they trusted that the study would be ‘trying to do something good’ and the details were not seen as particularly important. Two participants had concerns initially that the study may have been sponsored by condom manufacturers, which would have put them off participating in case the research was linked to sales promotions.

[Interviewer] Okay, and what did you think the research was for?

[Clinic user] I’m sure she did say but I can’t actually remember right now.

[Interviewer] No, that’s okay, I mean, did it matter to you?

[Clinic user] Not especially, I think obviously if there had been a commercial element to what she was asking I probably would have been fairly sceptical, I think […] I mean, if she’d said I’m from Durex and I’m trying to find out about people’s sexual patterns so we can flog them more stuff I probably would have been slightly dubious about that [….] obviously I’m aware of who UCL are and I know they’re a very good research university. And obviously I’m aware of what the NHS is, so either of those two things, kind of, absolutely no issue. (Male interviewee ID 353, Control group)

Views of iPads in clinic waiting rooms

All three of the clinics offer sexual health appointments on a drop-in basis, and the waiting time varies by time of day and day of the week. The iPads were positioned so that men could access them while waiting to see clinic staff. The placement of the iPads varied. In one clinic, the research was conducted in the waiting room and in two, participants were taken to a side room to complete research procedures and see the Men’s Safer Sex website in private. Staff described the tensions between making the iPad accessible in the main waiting room (and thus increasing access), and offering privacy to participants. Some felt uncomfortable approaching potential participants and explaining the study in a public waiting room, especially since the study focused on men who have sex with women, and staff sometimes knew that there were men who have sex with men in the waiting room who would not be eligible. Male participants agreed that privacy was important, and most felt happy with the location of the iPad that they had experienced.

The staff interviewed had been concerned that patients might be worried about missing their appointments, and one of their important roles was to ensure that this did not happen. Participants’ worries about missing appointments were pre-empted when staff agreed to hold their places in the queue for appointments.

Attitudes towards online consent

Staff expressed mixed opinions of the self-directed online consent. While it lessened paperwork and in theory should have saved staff time and effort, many felt duty-bound to obtain verbal consent as well, worried that participants may skim-read or fail to understand. In line with this concern, several male interviewees said that they had scanned the consent pages, and others were unable to recall specific details (although this may also reflect difficulties recalling details two or more weeks after enrolment). The study materials featured University College London and NHS logos, and men interviewed trusted that researchers would protect their anonymity and safety and were not interested in the details of this.

[Interviewer]… any other problems at all with the consent process?

[Staff member]… it seemed like, I don’t know whether quite a long information sheet on there….. and, I think, a lot of people were sort of… you felt like they were whizzing through it; and you’re thinking, you can’t possibly be reading this…. and, obviously you’ve got to have all the information in there…..and I don’t know how you get around that; but some people seemed a bit, you know, huffing and puffing because they were reading through it all, and then they’d scroll up and they’d realise there’s another [unclear]. And I could see people being, oh, for God’s sake, but I didn’t stop them obviously, they’ve got to read it. So I don’t know how you get around that because you’ve got to have all the information in there. You have to have graphics don’t you, but I’m sure there must be a way that you can bullet point it. I wonder if bullet points would be better? (Staff member 9, Clinic 1)

Technical problems with software and Wi-Fi access

There were substantial errors in the software that impacted on recruitment of eligible participants, and upon data collection and access to the intervention.13 It was difficult to set up and maintain access to Wi-Fi for patients in clinic waiting rooms since the process for permission and set up was complicated. Internet connections were often poor, and staff were not always confident about remedying Internet access problems. There was a faulty algorithm for participant selection, failure with automated web-analytic data collection, and faults in the login process for website and questionnaire access, which were not detected by pre-trial manual testing of the online trial software. The research team tested the algorithm manually, but automated testing was not carried out by the software development company. These problems were frustrating for men as well clinic staff and researchers.

[Staff member] The Wi-Fi, we had a nightmare with that, and that genuinely like was a problem because, you know, you’d get people in, they’d sit down and they wouldn’t be able to do it, and it was just so infuriating because they could have been eligible, they could have been, you know, and I had one guy who was so desperate to do it but the Wi-Fi wasn’t working, and it’s just things like that. (Staff member 9, Clinic 1)

[Clinic user] I mean, the only bad thing about the trial was, the follow-up questionnaire, when you had to click the link, it didn’t work…. from the website, so I had to email in, saying I can’t get in….. and it turned out the problem was, that if you already logged in, instead of taking you to the questionnaire, it took you to your account page…I was bothered enough to… having already done the first thing, I was kind of like, well, if they’re not aware of the issue, then no-one’s going to complete it, and the whole thing is going to be a waste of everyone’s time. (Male interviewee, ID 340, Control group)

Online research procedures

Men were required to complete online research procedures before the intervention group participants were shown the Men’s Safer Sex website (eligibility questions; study information; consent; setting up a user account; baseline demographic and sexual health questionnaires). The research procedures were a barrier to engagement with the intervention since they took some time to complete. Web analytics showed that a third of intervention group participants in the feasibility RCT did not actually see the Men’s Safer Sex website.13

[Staff member] It’s hard to get people to interact with it, I think, because of the… but that’s because of the way the research is done. […]. So for example when I was… so when the patients are doing this it can often take quite a while to get through all the data that you require. So, things like demographic data, and there’s stuff about, I don’t know, sexual preferences, sexual performance, all that kind of stuff, it takes a while to get through. And then by the time they do actually get to the website they aren’t really engaged to use it for that long. Like, a lot of patients would, kind of, just say, I don’t know. Can I go? (Staff member 1, Clinic 1)

Online outcome questionnaire

The online trial outcome questionnaire contained questions concerning condom use which were acceptable to all interviewees (see Appendix 1). Interviewees said that they were honest in their questionnaire responses, and some commented that it was easier to be honest online than in person. Some interviewees didn’t realise the distinction between the Men’s Safer Sex intervention website and the outcome questionnaire (so were not clear whether they were in the intervention or control groups).

[Interviewer]: Did you mind being asked about sex and relationships?

[Clinic user] No no. I think this is what the study is all about so if I minded then I wouldn’t have entered it. (Male interviewee, ID 372, Control group)

[Interviewer] It’s just good for us to know, but were you honest in the answers that you gave in the questionnaire?

[Clinic user] Yes…. You know, I don’t see the point in saying, oh, I’m not talking about that, because it, at the end of the day, it can potentially harm the research, because you’re not getting the true picture, and it doesn’t…you know, it’s very unlikely that I’m ever, you know, going to knowingly meet any of the actual research team, you know, so… (Male interviewee, ID 355, Intervention group)

Potential impacts of the study

We asked whether being in the study had had any positive or negative effects on men’s lives (asking in interviews and in a free text comment box at the end of the RCT online surveys).

Possible impact of the outcome questionnaire alone

The act of filling in the online survey questions prompted reflections on their attitudes or behaviour for some men in the control group.

[Free text question] Has being a part of this study had any good or bad effects on your life?

[Free text comment] I think it has been a positive experience. I found being submitted [sent] the same questions over and over and having to answer them, offered me the chance to ponder over this topic that often I might have overlooked. It has made me feel more conscious about my sex life. (Participant 332, Control group, comment on 12-month questionnaires)

[Free text comment] It’s been good because it’s a little reminder to be careful if I were to cheat and it reminds me of going to get tested at the hospital and how much I hated it and it’s much easier just to wear a condom. (Participant 215, Control group, comment on 12-month questionnaire)

[Interviewer] Were you honest in your answers? And it doesn’t matter if you were or you weren’t.

[Clinic user] Interesting enough, I think that I wasn’t being honest to myself but when I had to do the test and the questions are put in front of you then I started to realise how much I wasn’t being honest in my head… that’s what made me realise I had to change my life. That’s when the study helped me so much. (Male interviewee ID 372, Control group)

For other men, filling in the outcome questionnaire had no apparent impact.

[Free text comment] I am not learning anything new, so it is not having any effect on my life beyond taking up some time and providing me with Amazon vouchers…. (Participant 167, Control group, comment on 3-month questionnaire)

Men's (views) views of the possible effect of the intervention

[Free text question] Has being a part of this study had any good or bad effects on your life?

[Free text comment] It has helped me understand more about the way that STI can be transmitted (Trial participant 207, Intervention group, comment on 3-month questionnaire)

[Free text comment] It has been helpful to revise good practice for safer sex. The study has reminded me of risk but not necessarily offered any new solution. I can’t help but feel you are trying to promote condoms, an old message. Everything on the website comes back to ‘use a condom’. People, including me take absurd risks because sex with a condom is not the same thing as sex without. There are condoms that work a little better. Your website hedges around actually recommending a brand or type on the grounds of pleasure. That’s what people want to know. Is there a condom that I can forget that I’m wearing? (Trial participant 208, Intervention group, comment on 12-month questionnaire)

[Free text comment] Good. I am more responsible in the fact I’m more open to talking about contraception and protection. (Trial participant 304, Intervention group, comment on 3-month questionnaire)

[Free text comment]…in a good way I feel that this study has really challenged my sexual habits and made me question why I put my health at risk for a few seconds of intense pleasure when using condoms is not a chore and could save my life. (Trial participant 218, Intervention Group, comment on 3-month questionnaire)

Some men felt that the Men’s Safer Sex website content and focus was not relevant for them, either because they were already familiar with safer sex messages, or because of their relationship situation:

[Free text question] Has being a part of this study had any good or bad effects on your life?

[Free text comment] Not really to be honest. I feel that generally speaking it was very obvious the advice that was given, although I do think it is very important to make people aware of some things that perhaps some people do not see as being obvious. Personally I found it obvious and I do not feel that it has had any effect on my sexual practice or my wellbeing. However I am grateful to have taken part and I wish you all the success with your study :) (Trial participant 304, Intervention Group, comment on 12-month questionnaire)

[Free text comment] I appreciate the study and fully support it, but as I am in a long-term relationship with a single partner, I find that a large amount of questions do not apply to me. (Trial participant 137, Intervention group, comment on 6-month questionnaire)

There were no serious reported adverse effects of the study, but one man described an adverse emotional impact:

[Free text question] Has being a part of this study had any good or bad effects on your life?

[Free text comment] Not really, I mean, it reminds me of the sadness of losing my long term girlfriend and also imagining her having sex with other people, which is quite painful to think about but, in terms of my own sexual psychology I think I am fine…… Honest answer…. you did ask!;) (Trial participant 304, Intervention group, comment on 3-month questionnaire)

The place of digital interventions in sexual health care

Male clinic users and clinic staff were positive about the role that digital interventions could play in terms of being a useful resource for sexual health information either before or after clinic appointments. Offering a web-based resource in sexual health waiting rooms was felt to be very appropriate.

[Clinic user] Well, I think there’s a great case for really reliable and non-preachy information, because it’s not easy to see the GP about it, so it’s the classic, perfect case for Internet information, but I mean, I gather this is a bit of an issue in all health. Information on the Internet, it’s a variable quality. (Male interviewee, ID 374, Intervention group)

[Clinic user] I think the ideal time to do it would be the waiting room beforehand because you’ve almost got a captive audience. You’ve got like, a marketeer’s dream, haven’t you, because you’ve got people who can’t go anywhere, who are already actually by virtue of being there, a little bit engaged with the subject you want to talk to them about… (Male interviewee, ID 353, Control group)

[Interviewer] So how useful do you think it would be, to have this website [the Men’s Safer Sex website], in a clinic?

[Clinic user] I think, very useful. As I said, I think it’s the time when people are thinking hardest about all this kind of stuff. When they’re reflecting hardest, and regretting hardest, and I think it’s the time when people actually… and it’s not done in a way, where… when you think you might have something, and you go online, obviously, it’s just a world of pain, kind of going on different forums, and everyone has an opinion, and everyone thinks they’re a doctor, and they’re coming… giving you the worst possible scenario, whereas this doesn’t. It’s kind of, it’s very kind of… it’s more like suggestions and advice, but there’s no kind of like… you’ve got something terrible. (Male interviewee, ID 367, Intervention group)

It was suggested by men and by clinic staff that the website could be particularly useful for younger men, for low-to-medium-risk patients, and those who did not want to discuss their sex lives in person. However, interviewees acknowledged that it could be a challenge engaging men’s interest in a digital intervention, and difficult to change behaviour.

[Staff member] Like, how are people going to find it in the first place and engage with it, I think is the problem. And then the second problem is how would you direct people towards it? Would people self-direct towards it? It’s probably unlikely or, I don’t know, maybe you can encourage people or… it’s, kind of, hard to know what would make someone use it in the first place. Like, you’d really have to look. Yes. It’s a tricky one, really. I’m trying to think what would motivate people to go and have a play with it.

… I’m a bit sceptical of it all, to be honest. Because I think changing people’s behaviour is a very hard thing to do, and I think that I’m not sure that this level of intervention is going to do that because I think it would need to be more… I’m… what’s the word I’m looking for… more intensive to change someone’s behaviour, really. I’m not convinced that something so short will, but that’s just my personal view. (Staff member 1, Clinic 1)

Opportunities for digital health in the NHS

Participants felt that digital interventions for sexual health are useful, and that clinic staff could have a role in offering digital resources routinely. This would mean that the content would be trusted if it was endorsed by staff, and would also help to signpost clinic users to resources.

[Clinic user] If a clinician said here’s an information site, you know that that’s going to be trusted and that you’re not going to get a link to porn on it, or anything like that. And so I think giving them a card or certainly some sort of signpost to it would be good. (Male interviewee, ID 353, Control group)

Participants commented on current NHS digital capability, and they made suggestions for greater exploitation of digital health by the NHS.

[Interviewer] And can you see any other ways digital interventions could be used for sexual health? Do you have any thoughts on that?

[Staff member] We haven’t even got a website for the department, it’s infuriating. I come from a business background, patients don’t even know what clinics we have, opening times. One of the biggest problems we have is people have been on the Internet before they get here, and they come with all sorts of information, or misinformation. I would love a website that had many links which was the bible that we use. […] it’s still 1970 out there, they don’t collect people’s emails, we’re actually collating a massive database just by the sheer nature of them attending here, and we could actually be emailing them links, we could be emailing… some people do want this stuff and they have the right [unclear], but it’s another way of getting information out there. Encouraging people to retest, it’s your annual retest time, have you thought about it? We’ve got a database of people that we know that we could send to, but we’re missing that opportunity. (Staff member 2, Clinic 1)

Clinic staff felt that the website could have a useful role in providing access to additional information for patients, at their convenience, but felt that a digital intervention could not and should not replace their role in communicating directly with clinic users. Men were also concerned that digital interventions should not replace direct contact with health carers but that both modes of communication can have different advantages.

[Clinic user] I think it would be good for the staff here, to be able to use it, it’s like if people have certain questions, about stuff, then they could show them this page, especially about certain facts, and everything, and how, like how to use a condom and stuff like that. Because a lot, a surprising amount of people, don’t know how to use stuff like that, so especially as well, because they obviously hand out condoms and stuff. But, there’s the Tailored for You section, which I had a look at, and it kind of tells you the different brands, that are suited for different like, sizes and stuff. (Male interviewee, ID 360, Intervention group)

[Clinic user] I don’t like the idea of it being used in a consultation because I, kind of, want to speak to the clinician then who’s the expert. You know, sometimes clinicians ask a second question, which actually prompts an outpouring of something that proves to be really useful and really, kind of, helps pinpoint a problem. I think if they were to just shove an iPad under your face, you click it a couple of times and go, yes, that’s great, and then go, you wouldn’t impart that information. (Male interviewee, ID 353, Control group)

[Staff member] Do you know how I would use this? If I’ve got let’s say… if I’ve got somebody that’s exhibiting lots of this behaviour, nobody likes to be lectured. Most behavioural changes comes from self-exploration or self-initiation. The more tools you have that can expose that, that can make them come to their own self-realisation, the better. (Staff member 2, Clinic 1)

[Staff member] I think anybody who comes to the clinic has… we should be promoting it. It’s not there to substitute any health education that we provide, it’s not there to substitute CBT [Cognitive Behavioural Therapy] that the psychologist might want to give to the patient, or motivational interviewing that the health advisor might want to do. It’s there as an additional tool to… that is accessible 24 hours a day to the patient. And there’s nothing wrong with us making an advert of it in the clinic or having a computer where patients can go and interact with in the waiting room, or having it as an app that they can access on their phones from home. […..] We cannot be replaced by robots; this can only provide information but it almost ends up being almost one way because it’s quite a rigid system. It can only give you information based on the questions that are already set on the system. It doesn’t have the ability to pick up behaviour, it doesn’t have the ability to pick up any verbal cues that young people might be asking or be uncomfortable with so it can’t prompt, so it doesn’t replace human beings in any way, shape or form. [….] I think is has a role and we can use it as a tool. I don’t think it should be there to replace what we do. (Staff member 8, Clinic 2)

Discussion

Digital interventions such as the Men’s Safer Sex website are useful for sexual health promotion in a clinic setting, especially if information is NHS endorsed and if staff signpost people to it. Pre-appointment waiting time offers a good opportunity for a sexual health intervention; however, staff and clinic users felt that a website should supplement rather than replace face-to-face healthcare. Offering information online is especially useful for topics that men may wish to find out about in private, and staff felt that a sexual health website can offer a useful avenue supplement to clinic-based health promotion.

The pilot RCT fitted well around clinical activities, but men did not self-direct to the iPads. Participants and clinic staff felt frustrated by the multiple technical problems which hampered registration and data collection, and staff were more concerned about consent and confidentiality than clinic users. The outcome questionnaire was thought-provoking for some men, and could constitute an intervention in itself. Being asked to reflect about their sexual health prompted resolutions to change behaviour for some men (for both intervention and control participants), but an adequately powered three-arm RCT is needed to measure the effect of the Men’s Safer Sex website, and to test whether outcome measurement alone results in behaviour change.

Study limitations

We interviewed all staff who were directly involved in the conduct of the Men’s Safer Sex trial at the three sexual health clinics. However, we interviewed only 11 male pilot trial participants (due to researcher sickness), and their views cannot be taken to be representative of other trial participants, particularly of men who declined to join the study or those who withdrew. Similarly, comments left in the free text boxes on outcome questionnaires do not represent the views of the wider study sample (RCT participants). However, the free text facility was provided to capture unanticipated adverse effects, and no participants reported serious concerns.

Participants in the qualitative study were interviewed 2 weeks after they had registered for the study, to enhance recall. This means that we do not have information about user views of follow-up procedures (emails, text and telephone calls), or men’s reactions to email prompts to use the website. For the intervention group, it is not possible to separate the potential impacts of the research procedures (online outcome measurement+/− a qualitative interview) from the impact of viewing the Men’s Safer Sex website on self-reported attitudes and behaviours.

Despite the small sample size, this qualitative analysis gives useful insight into research procedures, clinic staff and men’s views of digital interventions for sexual health and their potential utility for male sexual health clinic users, and the challenges for implementation of digital interventions for sexual health in clinic settings.

Technical problems and patient Wi-Fi access

We encountered serious technical problems with the trial software, and with access to Wi-Fi for patients in clinic waiting rooms. The NHS lags behind many other institutions in terms of access to digital services,17 and it is vital that these issues are addressed if the NHS is to exploit the potential for digital interventions. Technical facility such as freely available reliable Wi-Fi is necessary for both patients and clinicians to benefit from mobile and computer-based applications.17

We found that while patients and staff supported the idea of digital sexual health promotion, it was not offered by staff or taken up by patients without prompting. Digital systems are already in place in many NHS settings, and these provide an opportunity to offer sexual health promotion, for example in conjunction with online appointments, electronic history-taking and risk assessment, online self-testing, and automated results and recall systems.5 Integration of digital health interventions into routine NHS clinical systems would encourage uptake and engagement, with the advantage of enhancing patient trust in an initiative through NHS endorsement.

Staff were sometimes unsure about how to solve technical problems such as loss of Wi-Fi connectivity; the digital skills and confidence of the NHS workforce need to be strong so that they feel confident to recommend digital interventions and services to patients. Staff and clinic users felt that digital and face-to-face services had different and complementary roles in addressing health care needs, and were concerned that digital interventions should not replace face-to-face healthcare. Considerable resource and care is needed to design digital systems which address the needs of patients and staff without causing frustration or an increase in workload: culture change is needed, with newly imagined ways of working.18

Ethical issues and online research

It is essential that research participants are given the information they need in order to give informed consent, and that confidentiality and data security are ensured.19 We encountered several tensions between these principles and practical realities of (online) research.

Informed consent online

Our online trial software required potential participants to establish their eligibility (through responses to nine online questions); to read study information online; indicate agreement on the consent form; create a unique account with a secure password; and then respond to demographic and sexual health questions before being offered access to the intervention website.13 Ethical committees require careful explanation to participants in writing of what is involved in research; however, research participants may not read this in detail, and instead make judgements based on their trust in researchers for example.20 Users do not like large amounts of text online,21,22 and we found that research participants did not read the information pages in detail. Some men appeared to be annoyed by the online research procedures.

Privacy and data security

The anonymity and convenience of an online environment is highly appropriate for sexual health research;6 however, the online environment opens up the potential for irreversible breaches of privacy and data security.19 Most email accounts are not secure (i.e. can be easily intercepted if transfer is not encrypted). It is also a risk that someone’s emails or texts may be read by another person, and that other people could see a website browsing history unless this is hidden or deleted. This type of breach of privacy could reveal that a participant had been to a sexual health clinic. Our information governance protocols required users to select passwords which are hard to guess, but this also makes them harder for participants to remember. The software security protocol also led to frustrating problems; for example, a password would be rejected if participants had entered a space at the end of the password on one occasion and not another.

We found that participants were not particularly concerned about consent and confidentiality, and there were no adverse events reported which related to consent or confidentiality. Participants’ trust was enhanced by the fact that this research was conducted by a university in partnership with the NHS, and participants did not generally wish to receive detailed information regarding the research.

To reduce the burden of information which is not of interest to a participant, the online environment offers excellent facility to offer bullet point summaries of study information, with links to full information for those who would like to find out more. Frameworks for assessing the ethical issues and potential risks of digital research (such as those developed by the British Psychological Society)19 would help researchers and ethical committee members to assess any potential risks of online research.23 The nature of possible risks can be outlined for participants, allowing participants to judge for themselves whether these are acceptable.

Online outcome measurement

Our findings indicate that filling in questions on sexual health can prompt reflection on sexual behaviour.24,25 It may be better to assess minimal outcomes only at baseline for several reasons: firstly to minimise the burden of the research procedures; secondly to increase time available for interacting with an intervention; and thirdly to reduce the effects of asking thought-provoking questions to all participants at baseline, which may reduce the apparent effect of an intervention.

Engagement with the Men’s Safer Sex website

Engagement with digital interventions for health promotion can be a major challenge.26 We placed the intervention in clinic waiting rooms to take advantage of the waiting time that is common in drop-in sexual health clinics; and staff and patients agreed this was an appropriate time to offer digital health promotion. A third of the feasibility RCT intervention group did not actually see the Men’s Safer Sex website,13 and this may have been due to technical problems, the time taken on enrolment and research procedures, and/or being called in for appointments.

It is very important to establish the effectiveness of a novel intervention, but research procedures themselves mean that the testing does not reflect the conditions for any future implementation. There is a tension between ensuring that the evaluation of an intervention is robust, and testing an intervention in circumstances which reflect a future implementation context.

Conclusion

Public health policy in the UK advocates the use of digital interventions for health, and they have the potential to offer cost-effective sexual health promotion.6 However, we encountered significant obstacles to online research, and to engagement with the Men’s Safer Sex website in NHS clinic settings. There are challenges for online trials of digital interventions which include ensuring the reliability of software, data security and confidentiality, patient access to IT in clinical settings, and patient engagement with digital interventions. An implementation study is needed to work out how best to maximise engagement with digital interventions, for example, integrating them into routine clinic pathways for sexual health care.6

The main message from our qualitative field work is that digital interventions for sexual health can be a useful supplement to NHS clinical care, but that technical problems and barriers to implementation and engagement must be ironed out before any potential benefits can be enjoyed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the men who participated in intervention development and in the trial, and to the clinical staff for supporting recruitment of participants. The Men’s Safer Sex website and RCT software framework were developed by Digital Life Sciences. The Men’s Safer Sex website is available at www.menss.co.uk.

Appendix 1

Contributorship

Julia Bailey led the study design and conduct, assisted by Rosie Webster. Lorna Hobbs conducted the interviews, Naomi Tomlinson and Julia Bailey led on the data analysis. All authors contributed to interpretation of results and to the submitted publication.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclaimer

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Ethical approval

City and East NHS Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13 LO 1801).

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) grant from the National Institute for Health Research. Reference number 10/131/01 http://www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hta/1013101 This study was commissioned by the HTA, and the design and conduct of the research is monitored by the HTA. The HTA had no role in data collection, analysis, or interpretation. Sponsor: University College London, UK.

Guarantor

Dr Julia Bailey. Anonymised data are available from Dr Julia Bailey.

Peer review

This manuscript was reviewed by Julie Bayley, University of Coventry and one other individual who has chosen to remain anonymous.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN18649610

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. One to one interventions to reduce the transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV, and to reduce the rate of under 18 conceptions, especially among vulnerable and at risk groups. 2007; 4-7-2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crosby R, Milhausen R, Yarber WL, et al. Condom ‘turn offs’ among adults: An exploratory study. Int J STD AIDS 2008; 19(9): 590–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green CA, Pope CR. Gender, psychosocial factors and the use of medical services: A longitudinal analysis. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48(10): 1363–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seymour-Smith S, Wetherell M, Phoenix A. ‘My wife ordered me to come!’: A discursive analysis of doctors’ and nurses’ accounts of men’s use of general practitioners. J Health Psychol 2002; 7(3): 253–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey JV, Mann S, Wayal S, et al. Digital media interventions for sexual health promotion-opportunities and challenges. BMJ 2015; 350: h1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey JV, Mann S, Wayal S, et al. Sexual health promotion for young people delivered via digital media: A scoping review. Public Health Res 2015; 3(13): https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/phr03130/#/abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey JV, Murray E, Rait G, et al. Interactive computer-based interventions for sexual health promotion (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 9: CD006483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lustria MA, Cortese J, Noar SM, et al. Computer-tailored health interventions delivered over the web: Review and analysis of key components. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 74: 156–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: A meta-analysis. AIDS 2009; 23(1): 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noar SM, Pierce LB, Black HG. Can computer mediated interventions change theoretical mediators of safer sex? A meta-analysis. Human Comm Res 2010; 36(3): 261–297. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webster R, Gerressu M, Michie S, et al. Defining the content of an online sexual health intervention: The Men’s Safer Sex website. JMIR Res Protoc 2015; 4(3): e82.0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webster R, Michie S, Estcourt C, et al. Increasing condom use in heterosexual men: Development of a theory-based interactive digital intervention. Transl Behav Med 2015; 6: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey JV, Webster R, Griffin M, et al. The Men’s Safer Sex Trial: A feasibility randomised controlled trial of an interactive digital intervention to increase condom use in men. Digital Health 2016; 2: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray E, Khadjesari Z, White IR, et al. Methodological challenges in online trials. J Med Internet Res 2009; 11(1): e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horvath KJ, Nygaard K, Danilenko GP, et al. Strategies to retain participants in a long-term HIV prevention randomized controlled trial: Lessons from the MINTS-II study. AIDS Behav 2012; 16(2): 469–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NHS England. Five Year Forward View. 2014. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed 8 Feb 2017).

- 17.Imison C, Castle-Clarke S, Watson R, et al. Delivering the benefits of digital health care. Research summary. 2016. Nuffield Trust. 29-8-2016. www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/delivering-the-benefits-of-digital-health-care (accessed 8 Feb 2017).

- 18.NHS England. A digital NHS for everyone. 2015. www.england.nhs.uk/2015/12/digital-nhs (accessed 8 Feb 2017).

- 19.British Psychological Society. Ethics Guidelines for Internet-mediated Research. 2013. http://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/Public%20files/inf206-guidelines-for-internet-mediated-research.pdf (accessed 8 Feb 2017).

- 20.Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Obtaining Informed Consent From Patients: Brief Update Review. In Making Health Care Safer II: An Updated Critical Analysis of the Evidence for Patient Safety Practices, Ch. 39. 211. 2013. Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments.

- 21.McCarthy O, Carswell K, Murray E, et al. What young people want from a sexual health website: Design and development of ‘Sexunzipped’. J Med Internet Res 2012; 14(5): e127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pal K, Dack C, Owen R, et al. Developing HeLP-Diabetes: Integrating theory and data to create an online self-management programme for adults with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2015; 32: 142–143.25307739 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allison S, Bauermeister JA, Bull S, et al. The intersection of youth, technology, and new media with sexual health: Moving the research agenda forward. J Adolesc Health 2012; 51(3): 207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholas A, Bailey JV, Stevenson F, et al. The Sexunzipped trial: Young people’s views of participating in an online trial. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15(12): e276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.French DP, Sutton S. Reactivity of measurement in health psychology: How much of a problem is it? What can be done about it? Br J Health Psychol 2010; 15(3): 453–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alkhaldi G, Hamilton FL, Lau R, et al. The effectiveness of technology-based strategies to promote engagement with digital interventions: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2015; 4(2): e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]