Abstract

Background

Online substance-use interventions are effective in producing reductions in harmful-use. However, low user engagement rates with online interventions reduces overall effectiveness of interventions. Identifying optimal strategies with which to engage users with online substance-use interventions may improve usage rates and subsequent effectiveness.

Objectives

(1) To identify the most prevalent engagement promoting strategies utilised to increase use of online substance-use interventions. (2) To determine whether the identified engagement promoting strategies increased said use of online substance-use interventions.

Review methods

The reviewed followed Cochrane methodology. Databases were searched for online substance-use interventions and engagement promoting strategies limited by study type (randomised controlled trial). Due to heterogeneity between engagement promoting strategies and engagement outcomes, meta-analytic techniques were not possible. Narrative synthesis methods were used.

Results

Fifteen studies were included. Five different engagement promoting strategies were identified: (1) tailoring; (2) delivery strategies; (3) incentives; (4) reminders; (5) social support. The most frequently reported engagement promoting strategies was tailoring (47% of studies), followed by reminders and social support (40% of studies) and delivery strategies (33% of studies). The narrative synthesis demonstrated that tailoring, multimedia delivery of content and reminders are potential techniques for promoting engagement. The evidence for social support was inconclusive and negative for incentives.

Conclusions

This review was the first to examine engagement promoting strategies in solely online substance-use interventions. Three strategies were identified that may be integral in promoting engagement with online substance-use interventions. However, the small number of eligible extracted studies, inconsistent reporting of engagement outcomes and diversity of engagement features prevent firmer conclusions. More high-quality trials examining engagement are required.

Keywords: Systematic review, internet, telemedicine, patient adherence, engagement

Introduction

Online interventions have been developed for a range of substance-use issues including alcohol reduction, tobacco and cannabis smoking cessation.1–3 Typically, they are delivered or supported via the internet and include web-based interventions such as internet-operated therapeutic software and online counselling and therapy. Meta-analyses have demonstrated effectiveness of online and computer-based substance-use interventions (SUIs) on behaviour change;4–7 however, engagement with the interventions remains a challenge.8,9

Engagement broadly refers to how the user interacts with the technology, typically measured by web-metric usage data. Engagement related behaviours include accessing the intervention website for the first time, using the intervention website and its features, as well as revisiting the website.10 Issues such as low login rates and limited use of intervention features are consistently reported in the literature with only a minority of participants returning to the online intervention.11–13 Studies suggest a dose–response relationship between the level of a user’s engagement and the effectiveness of an online health intervention.14–17 Whilst this association may also be due to reverse causality, such as when a user experiences better outcomes they are more likely to engage, it is plausible that engagement increases effectiveness and online intervention components are important strategies to improve rates of engagement.10 Additional individual and environmental level factors have also been hypothesised to influence engagement;18–20 however, this review is focusing solely on technology-based intervention strategies.

Previous reviews have examined engagement strategies predominantly for internet-based health behaviour change interventions. An early systematic review by Crutzen et al.10 examined strategies that facilitated exposure to internet-delivered health behaviour change interventions for adolescents. Eight out of 17 of the included studies were targeting substance-use, utilising strategies of targeted communication, customisation of information, tailoring, professional and peer support, interactivity, reminders and incentives. Two studies examining SUIs examined the effectiveness of engagement promoting strategies (EPSs) compared with a control, with neither study reporting significant differences for interactive or tailored features. By the term ‘tailored’, we refer to a process whereby intervention components are individualised to specific characteristics or needs of users, such as tailoring text messages to gender or drinking behaviours.21 When including all types of health behaviour change interventions the authors reported that multi-component strategies were the most effective. Brouwer et al.9 also examined exposure to internet-delivered health promotion interventions with qualitative descriptive analyses. Twenty-seven out of 64 studies in the Brouwer et al.9 study were targeting substance-use including EPSs of interactivity, peer and counsellor support, email/phone contact and frequent updates. The authors reported that the most effective strategies peer and counsellor support and email or phone contact.

Schubart et al.22 examined internet behavioural interventions for chronic health conditions in adults, using a positive deviance approach, where engagement strategies were compared between five studies with the highest, and five with the lowest attrition rates. However, none of the three studies included in the Schubart et al.22 study including SUIs were included in this comparison. Overall, the authors reported that tailoring, social support and updated material contributed to reducing non-engagement. Finally, Alkhaldi et al.23 conducted a review on the use of prompts to improve engagement with digital interventions and reported borderline positive results for prompts compared with no strategy.

Previous reviews have examined EPSs across a broad range of healthcare issues;9,10,22,23 however, no review has focused only on online SUIs. With the exception of Alkhaldi et al.,23 who focused on prompts for both online and offline interventions, no systematic review has been conducted on EPSs for online interventions since 2011. Furthermore, with the fast-paced development of new technologies, no review has included the use of smartphone or tablet based interventions. Finally, there is a lack of reviews considering only high quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs). As healthcare interventions moves towards mhealth, this review addresses the gap in the literature by examining the most up-to-date EPSs, considering only the studies of rigorous RCT design, to inform the development of future interventions.

The aims of this systematic review were: (1) to identify the most prevalent EPSs utilised to increase use of online SUIs; (2) to determine whether the identified EPSs increased engagement with online SUIs.

Method

Design

Systematic review of RCTs, following Cochrane methodology and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.24 The review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42016038874).

Definitions

Online health interventions

This review targeted online health interventions delivered or supported via the internet.25 This included but was not limited to smartphone apps, intervention-based websites, and online-delivered computer and tablet-based interventions. The definition of online SUIs also includes online interventions which can be used offline (e.g. apps). Online health interventions are differentiated from digital interventions, which are not dependent upon delivery or support from the internet, such as an analogue pedometer or a CDROM based computer program.26 Online SUIs were chosen because they represent the most up-to-date technology which is likely to supersede analogue (offline) interventions in the future.

Engagement

Engagement was defined by a user’s interaction with the intervention. This may be visiting a particular aspect of the online intervention or completing a task such as filling out an online diary. Engagement also included how long or how often the participant used the online intervention. Previous research examining engagement has reported a range of engagement outcomes including: number of logins to the intervention; time-spent on the intervention; specific web-sessions opened and tasks completed.17,27–29

EPSs

EPSs were defined as any method used to promote engagement with online SUIs. This includes prompts, tailoring of the intervention to its users; social support, online community and gamification features. Gamification is defined as the use of gaming components in non-gaming settings.30

Inclusion criteria

The eligibility criteria were selected based on participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and study designs. A start date of 1990 was chosen as it corresponds to the time period when the internet became available.31

Participants

All individuals accessing an online SUI, including, but not limited to, individuals accessing online interventions targeting alcohol reduction and smoking cessation. No age limit was imposed.

Types of intervention

EPSs delivered as a component of an online SUIs designed to increase use of said intervention. These were defined from a scoping review of the literature as prompts, tailoring, social support, online community and gamification features.

Intervention delivery format

Online SUIs as per the definition above including, but not limited to: mobile phones; tablets; web-based interventions; wearable technology with online capability; push notifications including text-messaging; social networks; online social support and social media.

Comparisons

(1) Online SUIs offering no engagement promoting strategies such as tailoring versus no tailoring; (2) online SUIs offering different levels of dosage of EPS such as low versus high dose of tailoring; (3) online SUIs offering alternative EPSs such as prompts versus tailoring.

Outcome

The main outcome was engagement with the online SUIs (measured as primary and secondary outcomes in included trials). This is typically reported as means of: number of logins; time spent on intervention (e.g. minutes); number of pages viewed; number of sessions completed; number of web-sessions opened; number of features used and tasks achieved.

Exclusion

The following were excluded: (1) trials examining CDROM and computer-based interventions which do not function in an online capacity; (2) trials where attrition from the trial (defined as drop-out attrition or loss to follow-up) could not be disentangled from attrition from the online intervention (defined as non-usage attrition); (3) studies which compared EPSs between different online SUIs; (4) studies which compared EPSs between an online intervention and offline health intervention. For (3) such studies were excluded as the effects of EPSs cannot be disentangled from the active ingredients of the behaviour change intervention.

Data sources and search methods

The search strategy combined online SUIs with engagement outcomes and EPSs limited by study type (RCT). The strategy was based on previously published systematic reviews on online health interventions and engagement with digital interventions4,10,32 and, in the case where systematic reviews had not been conducted on a specific topic, such as gamification, the search terms were based on the existing literature.33 The Medline thesaurus Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms were identified, supplemented by keyword searches and relevant filters. The data extraction tool was tested by one reviewer (JM) to determine whether 9 studies17,28,29,34–38 identified from a hand-search of the literature met the inclusion criteria. The Medline search terms are listed in Appendix 1.

The following databases were searched: Medline, PsychInfo, Embase, CENTRAL, CINAHL, Google Scholar (first 100 citations) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE). Unpublished literature was searched from OpenGrey and Index to Theses and Science Citation Index. Reference lists of included studies were hand searched and papers citing key papers screened.

Data collection and analysis

All studies identified were downloaded into EndNote X7 and duplicates removed. Two members of the review team independently screened article titles and abstracts (JM and SFC) in May and June 2016. Full texts were retrieved for relevant studies and eligibility assessed. If any discrepancies arose these were discussed by the two reviewers until a consensus was reached. Data from eligible papers was extracted into a template adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias.39 The extraction form was piloted using a representative sample of the studies by one reviewer (JM).

Data synthesis

Reporting was based on PRISMA guidelines.24 At protocol stage, meta-analytic techniques had been planned; however, they were determined to be inappropriate for comparison of the studies in the current review. This was due to high heterogeneity both in terms of outcomes as well as for type of EPS evaluated. The studies included evaluated a broad range of EPSs, including reminders, incentives and tailoring, and pooling these effects would not have been appropriate. Equally, there was high variability between outcome measures, which again were not appropriate for pooling. Consequently a modified version of narrative synthesis40,41 approach was used. Narrative synthesis is recommended by Cochrane when traditional meta-analytic approaches are not appropriate.42 As meta-analytic approaches were not appropriate, selection of a single primary outcome was not necessary (if studies reported more than one primary outcome), therefore, all engagement outcomes were reported.

Narrative synthesis adopts a textual approach and aims to provide both a summary of the knowledge-base and a rigorous evaluation, providing a robust interpretative synthesis of the effectiveness of the intervention in question. There were three stages to the modified approach to narrative synthesis: (1) developing a preliminary synthesis; (2) exploration of relationships in the data; (3) assessing the robustness of the synthesis product. A number of different tools and techniques are available for the stages above, depending on the type of studies included. At the beginning of the synthesis process the available tools and techniques were evaluated in terms of their relevance to the data by reviewer JM (see Appendix 2).

Assessment of risk of bias and robustness in included studies

Risk of bias was determined using the Cochrane’s Collaboration tool.39 Each study included was evaluated for risk of bias and was coded as low-risk, high-risk or unclear risk, taking into account random sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding, incomplete data and selective outcome reporting. Other bias was considered, including selection bias, sample size, power and baseline characteristic differences between groups. A risk of bias summary was generated (see Appendix 2).

Results

Summary of search results

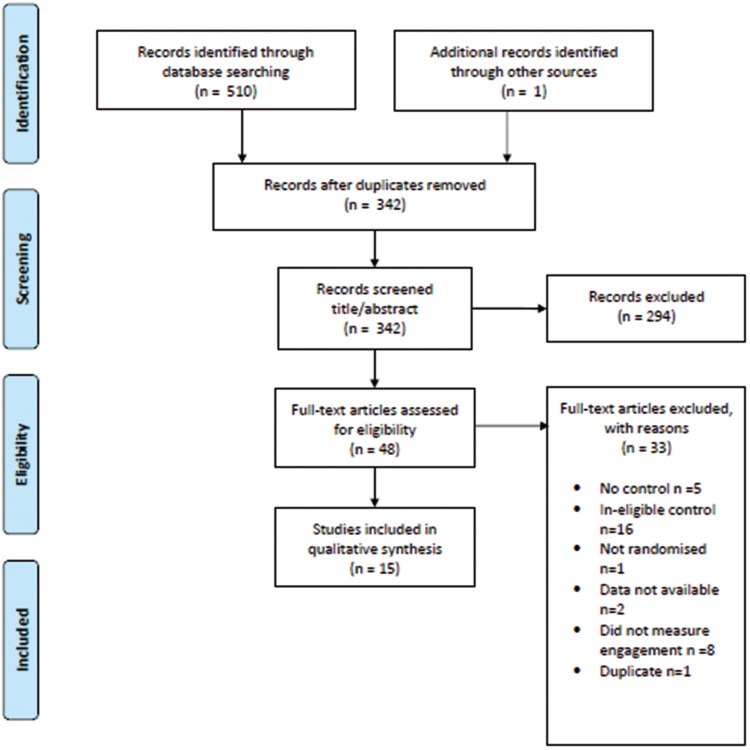

A total of 511 records were found. After removing duplicates 342 records were available for abstract screening. Of these, 48 studies went forward for full-text review. Thirty-three studies were excluded, the most common reason being lack of a suitable comparison group (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Characteristics of included studies

In total, 15 studies were included. All of the studies were computer, web-based interventions (as opposed to smartphone or tablet). Characteristics of studies are described in Table 1. Eleven studies targeted tobacco-use,29,35,43–51 three studies targeted alcohol-use2,53,53 and one study targeted cannabis-use.54 Two studies used a factorial RCT design35,29 and the remaining studies compared conditions with varying EPS types. The content and theoretical framework of the online interventions varied, but at minimum included information and advice for cutting down. Table 1 details the characteristics of the studies.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Author, year and location | Targeted substance/ health behaviour | Study characteristics | Description of DI | n participants | Characteristics of study population | Engagement outcome measure(s) | Reported engagement results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tailoring | |||||||

| Danaher et al. 2012 USA | Smokeless tobacco | Design: RCT (three arms) Participants: adult smokers Arms: (1) active control (basic version), (2) enhanced, (3) enhanced + EPS(s): tailoring/social support/reminders/multimedia recruitment: referral from smoking clinic DI format: web-based | Name: MyLastDip Arm 1 (basic version): included step-by-step instructions for best practices for cutting down and a resources section Arm 2 (enhanced version): provided above interactively with multimedia, personalised content; email reminders; goal setting and a web blog | N = 1716 (Enhanced = 857; basic = 859) | % male: 97% % White: 96% Age: 20.8 years, SD = 2.6 Readiness to quit: mean of 9 (SD 2.1) on an 11 point scale | (1) Logins (2) Duration of visit (min) | (1) Participants in enhanced version logged in more compared with basic** (2) Participants in enhanced version had higher duration of visit (min) compared with basic*** |

| Elfeddali et al. 2012 Netherlands | Tobacco | Design: RCT (three arms) Participants: adult smokers aged 18–65 years Arms: (1) basic version (action planning (AP) programme), (2) enhanced version (AP+), (3) control (questionnaire only) EPS(s): tailoring (basic vs. enhanced tailoring) Recruitment: online and print DI format: web-based | Name: Stay Quit for You (SQ4U) Tailored smoking cessation web-based programme using the I-Change Model58 Arm 1: basic included (AP): (1) tailored feedback before the quit attempt, (2) tailored planning strategy assignments before and after the quit attempt Arm 2: enhanced included above, plus tailored feedback after the quit attempt Arm 3: questionnaire only | N = 1812 (after exclusions) (Basic tailoring: n = 542, enhanced tailoring: n = 622, control: n = 648) | % male: 38% % White: not reported Age: 41 years (11.80) Readiness to quit: not reported | Number of planning assignments completed (six in total) | Participants in enhanced condition (AP+) completed more planning assignments than participants in the basic condition (AP)* |

| Houston et al. 2015 USA | Tobacco | Design: RCT (two arms) Participants: adult smokeless tobacco users Arms: three arms of increasing complexity EPS(s): interactivity/tailoring/social support/reminders/multimedia recruitment: online and print paid advertisements, radio DI format: web-based | Name: Decide2quit Arm 1: interactive, tailored quit smoking website. Including: motivational messaging tailored to readiness to quit; interactive risk, decisional balance, and cessation barrier calculators; informational resources Arm 2: enhanced version included above, plus a tailored pushed motivational email messaging system Arm 3: enhanced version + included the above ((1) and (2)) plus a social support group and communication with a trained tobacco treatment specialist | N = 900 (control = 299, enhanced = 164, enhanced+ = 437) | % male: 37% % White: 85% Age: 50% were 35–55 years (mean and SD not reported) Readiness to quit: 80% thinking about quitting | (1) Logins | (1) Participants in enhanced+ logged in more than the control*** (2) Enhanced+ vs. enhanced was non-significant |

| McClure et al. 2013 USA | Tobacco | Design: randomised fractional factorial design with four two-level intervention factors Participants: adult smokers Factors: participants randomised to one of two levels of each four factors: (1) Message tone (prescriptive vs. motivational), (2) navigation autonomy (dictated vs. not), (3) proactive email reminders (yes vs. no), (4) personally tailored testimonials (yes vs. no) EPS(s): tailoring/reminders recruitment: identified from automated health plan records DI format: web-based | Name: Q2 Tailored (to stage of readiness to quit and demographics) Internet based smoking cessation programme offering material addressing: the risks of smoking; benefits of quitting smoking; perceived barriers to treatment, perceived barriers to quitting; strategies for reducing smoking Factor 1: message tone (prescriptive/didactic vs. motivational) Factor 2: navigation autonomy (dictated order vs. not) Factor 3: proactive email reminders (yes vs. no) Factor 4: inclusion of personally tailored testimonials (yes vs. no) | N = 1865 | % male: 37% % White: 82% Age: 44.2 years (SD = 14.7) Readiness to quit: in next 30 days: 44% | (1) Website visits, (2) content pages viewed, (3) minutes online, (4) content areas viewed | (1) Tailored testimonials: no effect (2) Email reminders increased visits***, page views***, min online*** not content area views (3) Prescriptive message tone increased page** and content*** area views but not visits or min online (4) Dictated navigation increased content area*** and page views**, min online***, not visits |

| Severson et al. 2008 USA | Smokeless tobacco | Design: RCT (two arms) Participants: adult smokeless tobacco users Arms: (1) enhanced version, (2) basic version EPS(s): interactivity/tailoring/social support/reminders/multimedia recruitment: online and print paid advertisements, radio DI format: web-based | Name: Chewfree.com Arm 1 (basic version): included best practices to cut down and cessation information Arm 2 (enhanced version): arm 1 plus guided, interactive and tailored ‘planning to quit module’; ‘staying to quit’ module; multimedia content; two web-based support groups (peer and research staff; email reminders | N = 2523 (Enhanced = 1260; basic = 1263) | % male: 98% % White: 98% Age: 37 years, SD = 9.6 Readiness to quit: reported a mean of 8 (SD 1.8) on an 11 point scale (ref.) | (1) Logins (2) Duration of visit (min) | (1) Participants in enhanced version logged in more compared with basic*** (2) Participants in enhanced version had higher duration of visit (min) compared with basic*** |

| Strecher et al. 2008 USA | Tobacco | Design: Randomised fractional factorial design with five two-level intervention factors Participants: adult smokers Factors: participants randomised to one of two levels of each of the five factors: (1) outcome expectations, (2) efficacy expectations messages, (3) use of hypothetical success stories, (4) personalisation of the message source, (5) timing of message exposure EPS(s) tailoring/feedback strategies: Recruitment: identified from automated health plan records DI format: web-based | Name: not reported Core-intervention based on cognitive-behavioural methods of smoking cessation and relapse prevention including motivations for quitting, stimulus control and self-efficacy enhancement Factor 1: tailored outcome feedback expectations (high/low) Factor 2: tailored efficacy expectations messages (high/low) Factor 3: use of hypothetical success stories (high/low) Factor 4: personalisation of the message source (high/low) Factor 5: timing of message exposure (all at once/over a five week period with reminder) | N = 1866 | % male: 40% % White: 79% Age: 46 years (SD = not reported) Motivation to quit (mean on 1–10 scale): = 8.3 | Number of web-based smoking cessation sections opened by the participant | Regression analyses revealed that participants receiving high-depth tailored self-efficacy components*** and single exposure information opened significantly more web-sections*** |

| Tensil et al. 2013 Germany | Alcohol | Design: RCT (two arms) Participants: adult drinkers (18 or over who drank at level considered harmful or consumed more than 24/12 g (male/female) of pure alcohol per day on average in the past week) Arms: (1) original version, (2) revised version EPS(s): tailoring (original vs. enhanced) Recruitment: email DI format: web-based | Name: Change Your Drinking Internet-based self-help programme with automated tailored feedback. Based on solution-focused brief intervention59 and cognitive behavioural therapy Arm 1: includes drinking self-assessment, tailored feedback, goal planning, drinking diary and goal feedback based on motivational interviewing techniques60 Arm 2: revised version of above including more intensive daily short tailored feedback on the individual’s alcohol use and graphical display of alcohol use, detailed tailored feedback on alcohol use and tips on how to cope with risk situations on day 7, and advice for reflecting on reasons for reducing drinking and advice on rewarding achievement of goals | N = 595 (Original = 300, revised = 295) | % male: original = 59%, revised = 63% % White: not reported Age: original mean = 29.8 (10.3), revised = 29.0 (9.4) Measure of motivation to cut down: not reported | Diary usage (dichotomous: used at least once) | The usage of the diary was significantly higher*** in the revised version of the programme (diary used at least once, original version n = 167 (55.7%), revised n = 238 (80.7%) |

| Reminders | |||||||

| Danaher et al. 2012 USA | See Danaher above | ||||||

| Houston et al. 2015 USA | See Houstan above | ||||||

| McClure et al. 2013 USA | See McClure above | ||||||

| Muñoz et al. 2009 USA | Tobacco | Design: RCT (four arms) Participants: adult Spanish/English speaking internet users who smoked cigarettes Arms: (1) basic version, (2) basic + email reminders, (3) basic + email reminders + mood management lessons, (4) basic + email reminders + mood management lessons + social support EPS(s): reminders/social support/online therapist guidance Recruitment: online/word of mouth DI format: web-based | Name: or a Arm 1: static online smoking cessation guide covering: reasons to quit, cessation strategies, relapse prevention and management, pharmacological aids. Also included a cigarette counter and online journal Arm 2: Basic version + automated emails with links to sections of the GUIA keyed to quit date Arm 3: arms 1 + 2 and eight-lesson cognitive-behavioural mood management course Arm 4: arms 1 + 2 + 3+ online support group | N = 1000 (Arm 1 = 247; arm 2 = 251; arm 3 = 251; arm 4 = 251) | % male: 55% % White: 70% Age: 38 years, SD = 11.3 Confidence in quitting (as proxy for readiness to quit): mean = 6.8 on a 10 point scale (SD = 2.0) | As a proxy for engagement (1) cigarette counter usage, (2) online journal usage | Conditions with email reminders (2, 3 and 4) had increased cigarette counter*** and journal usage** compared with condition 1 (data not reported). Conditions 3 and 4 had increased cigarette counter usage compared with condition 2*** |

| Strecher et al. 2008 USA | See Strecher above | ||||||

| Severson et al. 2008 USA | See Severson above | ||||||

| Delivery strategies | |||||||

| Lieberman et al. 2006 USA | Alcohol | Design: RCT (two arms) Participants: adult drinkers Arms: (1) text based feedback, (2) multimedia based feedback EPS(s): feedback strategies (text vs. multimedia) Recruitment: online DI format: web-based | Name: Alcohol Check up Web-based alcohol screening and personalised feedback Arm 1: feedback presented in HTML formatting Arm 2: multimedia feedback that included an animated photograph of a woman’s face which personified the programme as she guided the user through the feedback modules | N = 288 Between arms not reported | % male: text = 62.8%, multimedia = 69% % White: text = 87.2%, multimedia = 86.8% Age: text mean = 37.2 (11.8), multimedia = 36.0 (12.1) Measure of motivation to cut down: not reported | Feedback modules viewed | Participants in the personified guide arm (multimedia) viewed significantly** more viewed feedback modules (3.9) than participants in the text-only group (3.7) |

| McClure et al. 2013 USA | See McClure above | ||||||

| Schulz et al. 2013 Netherlands/Germany | Alcohol | Design: RCT (three arms) Participants: adult drinkers (18 or over who drank at level considered unhealthy Arms: (1) wait list control, (2) summative feedback, (3) alternating feedback EPS(s): delivery (feedback) strategies Recruitment: online DI format: web-based | Name: Alcohol-Everything Within the Limits?! Three session, tailored programme targeting adult problem drinkers based on the I-Change model58 including personalised feedback and advice for cutting down drinking Arm 1: waiting list control Arm 2: summative feedback. All feedback provided at once after answering questions Arm 3: alternating feedback where participants received questions and personal advice alternately | N = 448 (Control = 135, summative feedback = 181, alternating feedback = 132) | % male: 57% % White: not reported Age: mean = 41.7 years old (SD = 15.7) Measure of motivation to cut down: not reported | (1) Programme completion | After the first session, drop out was significantly less in the alternating condition**. However, no differences in programme completion at three and six months |

| Stanczyk et al. 2013 Netherlands | Tobacco | Design: RCT (two arms) Participants: smokers, 16 years or older, motivated to quit, categorised as lower or higher educated participants Arms: (1) text based messages, (2) multimedia based messages EPS(s): delivery strategies (text vs. video) Recruitment: online DI format: web-based | Name: Steunbij Stoppen Web-based tailored smoking cessation programme based on the I-Change Model58 Arm 1: (text) tailored messaging delivered by text Arm 2: (video) tailored messaging delivered by video. All content between the two arms was identical | N = 204 (Text: n = 104, video: n = 100) | % male: text = 40.5, video = 22 % White: not reported Age: text mean = 46.6 (11.9), multimedia = 48.2 (12.0) Readiness to quit within one month (%): text = 19.2, video = 18.5 | Duration of visit (min) | Text condition spent a mean of 7.2 min online, video condition spent a mean of 7.8 min online*** |

| Strecher et al. 2008 USA | See Strecher above | ||||||

| McClure et al. 2013 USA | See McClure above | ||||||

| Social support | |||||||

| Danaher et al. 2012 USA | See Danaher above | ||||||

| Houston et al. 2015 USA | See Houston above | ||||||

| Muñoz et al. 2009 USA | See Muñoz above | ||||||

| Schaub et al. 2015 Switzerland | Cannabis | Design: RCT (three arms) Participants: adult (18 years and older) using cannabis at least once a week over the 30 days prior to study entry Arms: (1) original (web-based self- help programme), (2) original + chat counselling, (3) wait list control EPS(s): therapist guidance (online chat counselling) Recruitment: online and print DI format: web-based | Name: CanReduce Web-based tailored self help programme based on CBT,61 MI60,62 approaches consisting of eight modules delivered over a six week period. Arm 1: web-based self-help programme with up to two individual chat counselling sessions based on MI and CBT Arm 2: web-based self- help programme without chat counselling Arm 3: wait list control with participants receiving intervention after three months | N = 308 (Original = 114, original + chat = 101, control = 93) | % male: 75.3% % White: not reported Age: mean = 29.8 years old (SD = 10.0) Measure of motivation to cut down: not reported | (1) Module completion (2) Diary consumption completion | (1) Participants in the chat counselling arm (arm 1) did not complete significantly more modules than in the original arm (arm 2) (2) Participants in the chat arm completed significantly* more diary entries than in the original arm |

| Severson et al. 2008 USA | See Severson above | ||||||

| Stoddard et al. 2008 USA | Tobacco | Design: RCT (two arms) Participants: adult tobacco smokers Arms: (1) basic, (2) basic + social support (BB) EPS(s): peer support Recruitment: email to federal employees DI format: web-based | Name: Smokefree.gov Web-based self-help smoking cessation programme including online quit guide, self-help modules, 1:1 counsellor smoking cessation support, interactive risk tools, evidence-based risk tools and lists of clinical trials still recruiting smokers Arm 1 (basic): participants received the above intervention only Arm 2 (BB): participants received access to a forum where they could interact with other users | N = 1375 (basic = 691; BB = 684) | % male: 46.1 % White: 69.1 Age: 43.6 (SD = 10.3) Readiness to quit: not reported | (1) Duration of visit (min) (2) Visits to pages (tools) | (1) Participants in the BB group spent more time in minutes (mean = 18) on the intervention compared with participants in the basic group (mean = 11) (2) Visits to different pages did not notably differ between the basic and BB conditions, statistical tests were not conducted |

| Incentives | |||||||

| Ramo et al. 2015 USA | Tobacco | Design: RCT (two levels of randomisation: three arms randomised to Facebook group by stage of change, within each arm randomised to one of three incentive conditions) Participants: young adult smokers (18–25 years old) Facebook group arms: (1) not ready to quit, (2) thinking about quitting, (3) ready to quit Incentive arms: (1) no incentive, (2) personal condition: $50 gift card, (3) altruistic incentive: $50 gift card to charity EPS(s): incentives Recruitment: Facebook advertisement DI format: web-based | Name: Tobacco Status Project Description: a Facebook intervention tailored to stage of change; Transtheoretical Model strategies60 for cessation; group messaging (posts); CBT cessation sessions; ask the doctor sessions Arm 1: no incentive Arm 2 (personal incentive): $50 gift card incentive emailed to participant for commenting on all 90 posts posted to their Facebook group Arm 3 (altruistic incentive): $50 gift card incentive donated to charity for commenting on all 90 posts posted to their Facebook group | N = 79 Arm 1 (not ready to quit): n = 35 randomised to personal condition: 8, altruistic condition: 11, no incentive: 16 Arm 2 (thinking about quitting): n = 32 Personal condition: 9, altruistic condition: 8, no incentive:15 Arm 3 (ready to quit): n = 12 Personal condition: 3, altruistic condition: 3, no incentive: 6 | % male: 80% % White: 80% Age: 21 years, SD = 2.1 Smoking goal: 10% reported abstinence goal, 60% reduction goal, 30% no goal | As a proxy for engagement number of ‘likes’ and comments measured | (1) For enhanced sample: no significant difference among incentive conditions on number of comments made to Facebook groups (2) For those who commented at least once: personal incentive condition made more comments than other two conditions* |

| Stoops et al. 2009 USA | Tobacco | Design: RCT (two arms) Participants: adult tobacco smokers Arms: (1) Abstinence Contingent group (AC), (2) Yoked Control group (YC), EPS(s): Incentives Recruitment: local advertisements, word of mouth DI format: web-based | Name: Not given Intervention was an internet-based CO breath recorder which provided feedback and progress tracking Arm 1 (AC): participants received monetary incentives contingent on recent smoking abstinence (CO level of ≤4 parts per million) Arm 2 (YC): participants received monetary incentives independent of smoking status. Participants were matched to a participant in the AC group and were reinforced on a schedule identical to that of their ‘yoked’ partner | N = 68 (AC = 35; YC = 33) | % male: AC group: 26%; YC group: 24% % White: AC group: 94%; YC group: 94% Age: AC group: mean = 38 years, range = 21–58; YC group: mean = 40, range = 18–61 Readiness to quit: not reported | As a proxy for engagement number of videos posted to website was used as a measure of engagement | No significant effect of group on odds of posting videos to the website. AC group posted 68% of the total number of videos expected, YC group posted 67% of the total number of videos expected |

Note: *=<.05, **=<.01, ***=<.001. RCT: randomized controlled trial; EPS: engagement promoting strategy; DI: Digital Intervention; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; MI: Motivational Interviewing

Quality of included studies

The studies varied in quality and level of risk (see Appendix 2). An overall score of quality was calculated for comparative purposes by summing the ‘low risk’ scores for each bias category (see Appendix 3). The studies with the least bias were McClure et al.,35 Houston et al.45 and Stoddard et al.56 These studies reported rigorous methodologies and were of high quality.

Engagement outcomes were measured automatically so there was no blinding of outcome data bias. For missing outcome data, there was low risk of bias overall due to objective measuring. However, one study48 excluded 6% of participants who did not log on at all and another50 excluded 65 people who spent less than five minutes on the website, which may have introduced an element of bias. Engagement measures were only reported in three protocols57 but were pre-specified in the methods of 11 papers.29,35,43,45–48,52–54,56

There was potential bias of insufficient power in all studies as power analyses for engagement were not reported. Two studies47,51 had sample sizes of below 100 participants. Self-selection bias was found in the majority of studies, particularly for those who recruited using online and print advertisement.2,43,44,46–54

Research question 1: to identify the most prevalent EPSs utilised to increase use of online SUIs

Five individual EPSs were identified: (1) tailoring; (2) reminders (3); delivery strategies; (4) social support; (5) incentives. An additional category, ‘multi-component’, was created for studies which compared a basic version of an app with an enhanced version. Due to this study design, it was not possible to disentangle the effects of individual components of EPSs on engagement in these studies.

The most frequently reported EPS was tailoring, with seven studies (47%) using this technique. Ten different sub-types of tailoring techniques were identified (see Table 2). The most frequent sub-type of tailoring was to level of readiness to quit43–45,62 (40% of tailoring studies, n = 4) and to self-efficacy and barriers to quitting29,35,44 (30% of tailoring studies, n = 3). This was followed by tailoring to abstinence status,2,63 goals and motivations for quitting2,29 and testimonials/success stories (20% of tailoring studies, n = 2 for each sub-type). All other sub-types were included in only a single study.45

Table 2.

Prevalence of engagement promoting strategies.

| EPS category | N studies included (%) | EPS sub-category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tailoring | 7 (47) | ||

| Readiness to quit | 4 (40) | ||

| Self-efficacy + barriers to quitting | 3 (30) | ||

| Abstinence status | 2 (20) | ||

| Testimonials/success stories | 2 (20) | ||

| Goals/motivation to quit | 2 (20) | ||

| Interests | 1 (10) | ||

| Mood/negative affect | 1 (10) | ||

| Health + lifestyle factors | 1 (10) | ||

| Preparatory planning | 1 (10) | ||

| Personalised message source | 1 (10) | ||

| Reminders | 6 (40) | ||

| 6 (40) | |||

| Delivery strategies | 5 (33) | ||

| Multimedia (text/image/video) | 3 (60) | ||

| Single/staged/alternating feedback | 2 (40) | ||

| Message tone (prescriptive/motivational) | 1 (20) | ||

| Navigation autonomy (dictated vs. not) | 1 (20) | ||

| Social support | 6 (40) | ||

| Peer support | 5 (83) | ||

| Therapist support | 3 (50) | ||

| Incentives | 2 (13) | ||

| Contingent on abstinence | 1 (50) | ||

| Contingent on website comments | 1 (50) |

Reminders29,35,43,45,46,62 and social support54,43,45,46,56,62 were used in six studies (40%), delivery strategies29,34,35,49,53 in five (33%). All reminders were via email. The most popular delivery strategy techniques were using multimedia content34,49 and variations on the timing of delivery of content.29,53 Social support was either peer led,43,46,56 therapist led,54 or a combination of both.45,62 Incentives were used in two studies,47,51 including rewards contingent on abstinence or engagement. Two studies used a multi-component design.43,63

Research question 2: to determine whether the identified EPSs increased engagement with online SUIs

Effectiveness of EPSs

Table 3 provides an overview of the effectiveness of the different strategies. There was a lack of standardised reporting of engagement outcomes which made pooling of effects an unsuitable technique. Where independent effects could be reported, these are described under the relevant EPS category below. Unfortunately, due to two studies44,63 using a multi-component design comparing a basic with an enhanced version of a SUI, which included multiple EPSs together, examination of the effects of the individual strategies reported in these studies in Table 2 was not possible. The synthesis below includes only studies where individual effects of EPS categories could be reported.

Table 3.

Effectiveness of engagement promoting strategies in experimental arms.

| Tailoring | ||

|---|---|---|

| Author | EPS sub-type(s) | Significant |

| Tensil et al. 2013 | 1. Abstinence status 2. Goals/motivation to quit | Yes |

| Strecher et al. 2008 | 1. Goals/motivation to quit (depth outcome expectations condition) 2. Health + lifestyle (depth outcome expectations condition) 3. Self-efficacy + barriers to quittinga 4. Testimonials/success stories 5.Personalised sourcea | Yes |

| McClure et al. 2013 | 1. Testimonials/success stories 2. Self-efficacy + barriers to quitting | No |

| Elfeddali et al. 2012b | 1. Self-efficacy + barriers to quitting 2. Mood/negative affect 3. Level of planning | Unclear |

| Danaher et al. 2013c | 1.Readiness to quit 2. Interests | Unclear |

| Houston et al. 2015c | 1. Readiness to quit | Unclear |

| Severson et al. 2008c | 1. Abstinence status 2. Readiness to quit | Unclear |

| Reminders | ||

| McClure et al. 2013 | Yes | |

| Muñoz et al. 2009 | Yes | |

| Strecher et al. 2008 | Yes | |

| Danaher et al. 2013c | Unclear | |

| Houston et al. 2015c | Unclear | |

| Severson et al. 2008c | Unclear | |

| Delivery strategies | ||

| Lieberman et al. 2006 | Multimedia (imagesa vs. text) | Yes |

| Stanczyk et al. 2013 | Multimedia (videoa vs. text) | Yes |

| Strecher et al. 2008 | Single exposurea vs. staged | Yes |

| Schulz et al. 2013d | Single exposure vs. alternating feedback | Unclear |

| McClure et al. 2013d | 1. Dictated order of content vs. not 2. Message tone (prescriptive/motivational) | Unclear |

| Social support | ||

| Houston et al. 2015 | Peer + therapist support | No |

| Danaher et al. 2013c | Peer support | Unclear |

| Muñoz et al. 2009 | Peer support | Unclear |

| Schaub et al. 2015d | Therapist support | Unclear |

| Severson et al. 2008c | Peer + therapist support | Unclear |

| Stoddard et al. 2008d | Peer support | Unclear |

| Incentives | ||

| Ramo et al. 2015d | Contingent on website comments | Unclear |

| Stoops et al. 2009 | Contingent on abstinence | No |

Independent effects reported for specific sub-types.

Statistical tests not conducted.

These studies used a multi-component design so eliciting individual effects was not possible.

Inconsistent findings reported between engagement measures.

Tailoring

Seven studies reported tailoring as an EPS; four of these reported data for individual effects of tailoring as an EPS.2,29,35,45 Two reported significant increases in engagement compared with the control conditions,2,29 one reported increases in engagement measures compared with control but did not report statistical tests.45 There was high variability between the types of tailoring features used, with 10 different sub-types included overall (see Table 2). Four out of seven studies tailored to more than one factor at time, subsequently, unless specified, results of individual effects of sub-types must be considered with caution.2,44,45,63

Tensil et al.2 compared two self-help programmes which provided automated feedback tailored to abstinence status (drinking level). Both original and revised versions included tailored feedback on participants’ alcohol-use at baseline, general information on control strategies and a drinking diary. In the revised version participants received additional daily tailored feedback messages on abstinence status and goals/motivations to quit. The authors reported increased diary usage in the revised arm compared with those in the original arm. Individual effects of the tailoring sub-types were not reported.

Strecher et al.29 used a factorial design allowing for comparison of sub-types of tailoring EPSs, randomising participants to one of two levels of five different treatment components, four of which compared a high level of tailoring with a low level of tailoring. The tailoring components were: (1) depth of outcome expectations (such as health and lifestyle factors and motivations for quitting); (2) depth of efficacy expectations (such as barriers to quitting); (3) depth of success stories where participants received a hypothetical story tailored to the participant; (4) ‘personalised source’ where messages were presented as either friendly or informal. Analyses revealed that participants receiving high-depth tailored self-efficacy components and high-depth personalised source components opened significantly more web-sections.

Elfeddali et al.45 compared two versions (low and high) of a tailored web-based programme targeting smoking cessation in adults whereby the level of tailoring was manipulated. A questionnaire only control condition was also included. In the low tailored group respondents received tailored feedback prior to their quit attempt. Feedback was tailored to: self-efficacy, readiness and motivations to quit and preparatory planning. In the enhanced group (AP+) participants received additional tailored feedback post-quit attempt to self, efficacy, recovery self-efficacy, mood/negative affect and level of planning. Providing additional tailored feedback after the quit attempt resulted in more planning assignments being completed, suggesting that a higher dose of tailoring, consistent with Strecher et al.29 above, is more effective. However statistical tests were not completed.

McClure et al.35 used a factorial design, randomising participants to one of two levels of the four experimental factors. One of these factors was tailored; participants received three highly tailored testimonials (or not) targeting self-efficacy. Tailored testimonials did not significantly affect engagement.

Reminders

Six studies reported reminders as an EPS.29,35,43,45,46,62 Four studies examined the individual effects of use of reminders, which are reported here. McClure et al.,35 using a high quality factorial design with a large sample size (n = 1865), randomised participants to one of two levels of four experimental factors. The authors examined whether reminders increased website visits, content pages and areas viewed and minutes spent online for an internet-based smoking cessation programme. Reminders significantly increased visits, views and minutes spent online compared with participants who did not receive reminders.

Muñoz et al.47 examined a basic version of an online smoking cessation guide compared with three other versions of increasing complexity. The basic version included an instruction guide, cigarette counter and online journal; the second version included the basic version plus reminders; the third included version two plus mood management lessons and the fourth version included version three plus social support. Conditions with reminders had significantly higher tool usage (cigarette counter and diary usage) than condition one.

Strecher et al.29 also used reminders in one factor of their five factor RCT. The authors reported that this EPS increased engagement; however, this result needs to be considered with caution as the use of reminders was combined with a manipulation of delivery strategy (timing of message source) so the extent to which reminders were independently associated with engagement is not known.

Finally Houston et al.46 delivered a quit smoking website, with three arms of increasing complexity: basic, enhanced and enhanced plus. The enhanced group included the intervention from the basic arm as well as the addition of email reminders; the enhanced plus included the same content as well as a social support feature. Participants in the enhanced plus logged in more times than in the basic version, but not compared with the enhanced version, suggesting an effect of reminders upon engagement.

Delivery strategies

Five studies reported delivery strategies as an EPS. For the purpose of this review, ‘delivery strategies’ refers to EPSs which manipulate the type of delivery method of the intervention, for example, text versus video. Three out of five of the studies reported increases in engagement.29,49,52 Multimedia delivery of information may be an important delivery strategy to promote engagement, as may be providing information all at once, as opposed to in stages. However, with the exception of Strecher et al.29 the studies in this EPS category were of low quality (see Appendix 3).

Two of the studies compared text-based with multimedia-based delivery formats (Lieberman52 and Stanczyk et al.49). Lieberman52 examined the number of feedback modules completed in a study examining text versus multimedia messages for an adult web-based alcohol screening and personalised feedback programme. In one arm participants received all feedback in HTML text, whilst in the other, feedback was delivered in multimedia format. The multimedia arm consisted of a ‘personified guide’, where results were presented by a photograph of a woman who would guide participants through the feedback process. Participants in the multimedia arm viewed significantly more feedback modules than participants in the text-only group.

Stanczyk et al.49 conducted a RCT examining the delivery strategy of feedback messages in a single session web-based smoking cessation programme. Participants received feedback either by text or by video. Participants in the video condition spent significantly more time online (minutes) than those in the text condition.

The three other studies manipulated the delivery schedule of feedback.29,35,54 Strecher et al.29 used a factorial design randomising participants to one of two levels of five different treatment components, one of which was the delivery strategy of the intervention materials. Participants received the materials either all at once (single exposure) or over the course of five weeks. Participants in the single exposure arm opened significantly more web-sections than participants who received the content over the course of five weeks. However, this result needs to be considered with a caveat: reminders were also included in this factor and it is not possible to disentangle which EPSs were having an influencing effect.

Schulz et al.54 conducted an RCT of a web-based, three session tailored intervention targeting problem adult drinkers. Participants were randomised to a control group or the experimental group, which was divided into two sub-groups: alternating and single exposure. In the alternating group participants received alternating questions (three in total) followed by personal advice. In the single exposure group, participants answered all the questions and were given the personal advice all at once. The feedback messages were the same for both groups. In the alternating condition, significantly fewer participants dropped out after the first session; however, there were no differences in programme completion at three and six months.

McClure et al.,35 using a high quality factorial design, manipulated navigational autonomy where participants could view content in any order or a pre-specified order. The authors also manipulated message tone, which was either prescriptive (in a didactic tone) or motivational. Dictated navigation significantly improved engagement on three out of four measures (content areas viewed, content pages viewed, cumulative duration), whereas prescriptive message tone significantly increased engagement on two out of four measures (content areas viewed, content pages viewed).

Social support

Six studies reported social support as an EPS.44,46,47,55,57–63 Four studies examined individual effects of social support features.46,56 Results for the use of social support as an EPS were inconclusive. Two studies reported peer social support as an EPS.54,46,56 Stoddard et al.,56 in a very high quality study with large sample size (n = 1375), examined the effect of a social bulletin board where users could interact with each other within a self-help smoking cessation programme. Stoddard reported two engagement outcomes: visit duration (minutes) and number of visits to pages; the authors reported an increase in visit duration but not in visits to pages.

Muñoz et al.47 also used social support as a strategy, including in one of the four arms of the trial was an online social support group. The arm with a social support feature did have higher engagement (cigarette counter usage) compared with the arm with only email reminders as an EPS. However, included in the arm with social support as an EPS was a cognitive behavioural mood management course, with may also have had a moderating effect upon engagement, therefore these results need to be considered with caution.

Another study reported online therapist guidance as an EPS. Schaub et al.,54 in a good quality study, examined whether the addition of chat counselling to a web-based tailored self-help programme for adult cannabis users increased feature usage (module and diary completion). The results for the two engagement outcomes were conflicting: participants in the chat-counselling arm did not complete significantly more modules than those in the original arm. However, participants in the chat-counselling arm did complete significantly more diary entries than those in the original arm.

Houston et al.46 included a peer and therapist led social support group in the enhanced plus condition of a three arm trial (basic vs. enhanced vs. enhanced plus) of a quit smoking website and reported that the addition of a peer and therapist led social support group did not increase engagement over the enhanced arm, which included the basic component plus reminders. As reminders in the enhanced arm increased engagement compared with controls, this suggests an effect of reminders not of social support.

Incentives

Two studies examined the effectiveness of incentives to improve engagement.48,52 These results were conflicting, with one study reporting increases in engagement only for participants who had already engaged. These studies were of low quality and reported small samples sizes (see Table 2).

Ramo et al.48 conducted a smoking cessation intervention on Facebook and examined the effect of different incentives on the number of likes and comments posted on the Facebook pages (as a proxy for engagement). There were three incentive conditions: (1) no incentive; (2) altruistic incentives where a $50 gift card was given to charity if participants commented on all 90 posts posted on the group’s Facebook page; (3) personal incentives where participants were given a $50 gift card for commenting on all posts. Analyses reported that there were no differences in engagement between incentive arms. However, for those who had already engaged and commented at least once, personal incentive condition made significantly more comments than the other two conditions.

Stoops et al.52 also examined whether incentives improved engagement with an online smoking cessation website; however, incentives were not specifically targeting engagement: participants either received incentives contingent on recent smoking abstinence, or received incentives independent of smoking status. The authors measured the number of online videos participants posted to the website, which captured participants giving CO readings. There was no significant effect of group on odds of posting videos to the website.

Multi-component designs comparing a basic version with an EPS enhanced version

Two studies compared a basic with an enhanced version of the intervention.44,63 The enhanced versions incorporated a range of EPSs including: interactivity; tailoring; multimedia; reminders; online therapist guidance and social support. Both studies reported significant effects between basic and enhanced versions. Due to the study designs it was not possible to examine the effect of the individual strategies, therefore the EPSs in this category were considered together. Danaher et al.44 compared a basic and enhanced version of a web-based smokeless tobacco programme targeting 14–25 year olds. The enhanced version included four additional strategies compared with the basic self-help programme (interactivity/tailoring/multimedia/reminders). The authors reported significant increases in logins and duration of visits for the enhanced version. In a similar study, Severson et al.63 examined the use of six different strategies (interactivity/tailoring/social support/reminders/multimedia) in an enhanced versus basic study for smokeless tobacco users. Both logins and visit duration (minutes) were higher in the enhanced version.

Discussion

This systematic review of the effectiveness of engagement promoting strategies in online SUIs has focused on evidence from RCTs, with the majority of studies targeting tobacco cessation. This review is the first to explore which EPSs are effective specifically in substance-use populations and the first to use Cochrane Methodology, with previous reviews examining more generally the health behaviour change literature.

Five different EPSs were identified: tailoring; reminders; delivery strategies; social support; incentives. Overall, the strongest evidence points to the use of tailoring, email reminders and multimedia and single exposure delivery strategies to improve engagement. Social support features demonstrate inconclusive results and may be effective in promoting some engagement behaviours but not others. Incentives did not demonstrate effectiveness.

Tailoring demonstrated promising results, which is consistent with previous research.18,22,66 Tailoring has been hypothesised to be effective because it adapts the intervention to specific attributes of the user.19 In the alcohol field tailoring has been demonstrated to improve the intervention by making it more meaningful and relatable to the user,67 increasing their likelihood of engaging with the intervention content. Tailoring to self-efficacy demonstrated tentatively positive results, with a higher dosage of tailoring improving engagement.29,45 Tailoring to goals/motivations to quitting was inconclusive as one study provided positive results,2 but in combination with another tailoring sub-type (abstinence status). The other study29 also included this sub-type in combination with another (health and lifestyle factors) but did not report an effect of higher dosage on engagement. Tailoring to a friendly, personalised source was effective, but was only examined in a single study,29 as was tailoring to abstinence status.2

There was high variability between the types and combinations of tailoring features used in this review (see Table 2) and disentangling which subtypes of tailoring EPSs are the most effective remains a challenge. Therefore these results need to be considered with caution: Only two studies29,35 examined effects of individual sub-components in isolation. Elfeddali et al.45 and Tensil2 examined tailoring sub-types of self-efficacy, abstinence status, goals and motivations, mood and level of planning in combination, therefore work is needed to experimentally study the influence of individual tailoring strategies to confirm these findings. Furthermore, the descriptions of how tailoring was utilised in the studies was often limited, and specific details on how tailoring was modified in the studies, for example how interventions were tailored to ‘self-efficacy’, were lacking, making it difficult for the design of future interventions to replicate the effective components.

In a recent meta-analysis, the use of reminders to improve engagement with digital health interventions showed small but significant results.23 This supports the findings from the current review. Given the wealth of research from the broader healthcare field for the effectiveness of reminders to improve engagement with healthcare services,68,69 there is again a need for further high quality research to examine the role of reminders in promoting engagement with online substance-use interventions.

The methods through which content is delivered demonstrate potential to increase engagement. Perski et al.18 highlight that when users have control over how they view content, and have free choice over when they interact with it, evidence points towards higher engagement rates. Equally, this review found that multimedia content had higher engagement rates than simple text based content. This maps onto the concept of usability and aesthetics, which have been demonstrated to be key factors in engagement.70,71 For example content which is well presented and easy to digest is more likely to be utilised than content which is difficult to navigate or read, which is supported by the findings in this review.

Social support, whether by peer or therapist, was an effective strategy to increase engagement in a previous review by Brouwer et al.9 However, in the current review, social support features were highly inconclusive and had differential effects on engagement depending on which engagement measure was used. This points to specific EPSs targeting different engagement behaviours. User engagement research has reported that social or ‘community’ features are highly desired in apps for cutting down alcohol-use.67 With numerous studies pointing to social support being a useful tool to promote behaviour change,72-74 further research is warranted.

It was surprising that the two studies examining the effect of incentives on engagement did not report positive results. In the substance-use field, providing voucher or prized-based reinforcement for abstinence from drugs as well as treatment adherence is effective.68,75 One potential moderator may be the influence of motivation level on engagement; in the present review, Ramo et al.48 saw an increase in engagement compared with controls only for participants who had already engaged by posting previously. If incentives work to promote engagement in users, it may only be in those motivated to reduce their use already; however, this hypothesis needs further testing.

The evidence also suggests that using a multi-component EPS approach is more effective than a single EPS. Both studies using this approach demonstrated an effect of multi-component strategies compared with no strategies. Furthermore, in the Muñoz et al.47 study, reminders were significantly more effective compared with a basic version, but the addition of social support was more effective than reminders alone, pointing towards an additive effect of using multiple strategies.

Various theoretical models have been proposed to explain the mechanisms behind user engagement with online health interventions. Persuasive system design has been influential in the engagement field, proposing that technology has the capacity to influence, reinforce, change and shape attitudes or behaviours through supporting users to achieve the main objective of the technology.76 Techniques such as monitoring, feedback, tailoring, aesthetic design, novelty, credible source and social support have been proposed to influence usage with online interventions.77,78 This model has been further extended by Short et al.20 to consider individual, environmental and technology level factors that may moderate engagement. In a recent conceptual review, Perski et al.18 hypothesise that engagement is directly influenced by the context, content and delivery of the intervention as well as characteristics of the population; however, further investigation into these associations is warranted as evidence is tentative. Engagement models have been concisely described in a scoping review by Ryan et al.79

All the studies were computer web-based, despite the increasing availability of app-based SUIs downloadable from the app stores.67 Coupled with a lack of evidence-based design for these programs,80 there is a need for rigorous evaluation of engagement in app-based interventions. How people use computer-based interventions may be different from how they use app-based interventions. For example, whether a smartphone or computer is being used may influence the amount of time a user engages with an intervention. Users may also respond differentially to engagement features depending on delivery mode. This review was unable to explore any of these issues; further exploratory work would be beneficial.

An inductive approach following Cochrane methodology was used here to identify EPSs. However, due to this rigorous approach there may remain EPSs identified in other frameworks that were not identified in this review, such as novelty, aesthetics and system credibility.18,19,81 Unfortunately, to date, these EPSs have not been evaluated using a RCT design within the SUI field, therefore whilst they are potentially promising techniques, further research is warranted.

One issue which has yet to be defined in the engagement literature is how best to measure it, both quantitively and qualitatively. As this review highlights, many different measures are used, with no consensus between researchers, and conflicting results, whereby an EPS will have antipodal effects on different engagement measures. Perksi et al.18 suggest that multiple dimensions of engagement should be utilised, for example self-report, web metrics and physiological or psychophysical correlates of e-health interaction. However, as Yardley et al.82 highlight, we still do not fully understand what constitutes ‘effective engagement’ and how to measure it. Engagement is a complex and dynamic behaviour, and it has been argued that simply ‘increased engagement’ measured via web metric data as is typical with existing RCTs might not equate to ‘effective engagement’. For example, non- or ceased engagement could signify that the intervention has been effective whilst sustained engagement might suggest that the user is not learning to self-regulate independently and is over-relying on the intervention. Therefore defining the most appropriate measures of engagement in the context of each individual intervention is important as a ‘one size fits all’ approach may disregard nuanced differences between engagement behaviours.

Limitations

The major strengths of this review are its rigorous methodology using Cochrane Guidance. However, fewer studies were identified than expected and meta-analytic techniques could not be applied as had been planned. The size of effect of the different strategies could therefore not be measured across studies, so reporting of results here is tentative. Further high-quality trials examining the effect of EPSs need to be conducted, reporting consistent engagement outcomes, in order for measures of effect to be established.

There was high heterogeneity of engagement outcomes reported in the studies, an issue which has been highlighted in previous reviews.9,22,23,83 Until a consistent measure of engagement is used by researchers, reviews comparing the results of different outcomes need to be considered cautiously. In the current review, four studies reported conflicting engagement results depending on the engagement measure used, demonstrating the inconsistencies different measures of engagement can produce. Future work needs to establish whether there is an optimal ‘engagement outcome’, or combination of outcomes, for future evaluations to consider. Brouwer et al.9 reported that different engagement features influenced different engagement behaviours, for example, peer support was associated with a longer website stay and email contact was related to more logins. This suggests that there may not be one outcome appropriate for measurement of all types of engagement strategies.

This review considered only high quality RCTs; however, it is recognised that as engagement is a complex and multi-faceted issue,84 studies employing other designs also provide important data to the field. Future work may benefit from consideration of qualitative work alongside RCTs to elucidate further the inconsistencies in findings.

Piloting of search strategy and review of relevance of techniques for narrative synthesis were conducted by only one reviewer (JM), potentially introducing bias.

It is noted here that only two of the RCTs in this review cited engagement as their primary outcome. Therefore the majority of studies may not have been powered to detect effects.

The majority of the studies examined adult smoking populations so the limitations in the generalisability of these findings are acknowledged. However, as the findings are in line with evidence from other healthcare areas, the results of this review are potentially applicable across the substance-use domain. It is also possible that the differences in effect of EPSs compared with controls were due to the EPS arms taking longer to deliver than controls and therefore required more user time and engagement. This is most applicable to the studies which examined an enhanced compared with a basic version.

Conclusion

This review has identified five strategies used to promote engagement in online substance-use interventions and has highlighted that interventions that use tailoring, reminders and multimedia and single-exposure delivery are potentially effective. The evidence for social support is highly inconclusive. Incentives need to be studied more thoroughly. Promoting engagement is crucial to optimally deliver the harm reduction interventions in online programmes; however, more consistent reporting of engagement outcomes and further research are still required.

Appendix 1. Medline search terms for engagement promoting strategies for online substance-use interventions

Terms for online interventions

(phone adj application*) or (phone adj app) or smartphone.mp,hw.

(virtual adj reality).mp,hw.

(Second life or secondlife).mp,hw.

(online adj (bulletin adj board*) or bulletinboard* or messageboard* or (message adj

board*)).mp,hw.

(online or on-line).mp,hw.

exp internet/ or ((internet adj based) or internet-based).mp,hw.

((web adj based) or web-based).mp,hw.

((world adj wide adj web) or (world-wide-web) or WWW or (world-wide adj web) or (worldwide adj

web) or website*).mp,hw.

((electronic adj mail) or e-mail* or email*).mp,hw.

(((mobile or cellular or cell or smart) adj (phone* or telephone*)) or smartphone).mp,hw.

(internet based or internet-based) adj10 (computer* or laptop*).mp,hw.

(web adj based or web-based) adj10 (computer* or laptop*).mp,hw.

(World wide web or world-wide-web or www or world-wide web or worldwide web or

website*).mp,hw.

(E-health or ehealth or electronic health).mp,hw.

(m-health or mobile health or mobilehealth or mhealth or tablet).mp,hw.

(cyberpsychology or cybertherap* or etherap* or ecounsel*).mp,hw.

(digital intervention* or mobile device*).mp,hw.

Exp Social media/

(Facebook OR LinkedIn OR Twitter OR Badoo OR Orkut OR Qzone OR Xing OR Tencent OR Weibo OR

Mixi OR Sina Weibo OR Hyves OR Skyrock OR Odnoklassniki OR Wer-kennt-wen OR V Kontakte OR

Tuenti OR MySpace).mp,hw.

(interactive adj ((health adj communicat*) or televis* or video* or technolog* or

multimedia)).mp,hw.

(blog* or web-log* or weblog*).mp,hw.

((chat adj room*) or chatroom*).mp,hw.

AND

Engagement Outcomes

Engagement.mp,hw.

Attrition.mp,hw.

Adherence.mp,hw.

Exp Patient Dropouts/

Exp patient compliance/

(process adj metric*).mp,hw.

website-us*.mp.

website us*.mp.

(Web us* or web-us*).mp.

(website adj5 usage).mp,hw.

(web adj5 usage).mp,hw.

(online adj5 us*).mp,hw.

Usage.mp,hw.

Login*.mp,hw.

log-ins.mp,hw.

(page* adj5 view*).mp,hw.

(module* adj complet*).mp,hw.

(session* adj complet*).mp,hw.

(visit* adj5 website*).mp,hw.

((Intervention adj participation) or (website adj participation) or (online adj participation) or (web*

adj section* adj open*) or (web adj page* adj visit*) or (time adj spent adj online)).mp,hw.

AND

Engagement promoting strategies

(prompt* or reminder* or (push adj notification*)).mp,hw.

((chat adj room*) or chatroom*).mp,hw.

((bulletin adj board*) or bulletinboard* or messageboard* or (message adj board*)). mp,hw.

((social adj support) or (peer adj support) or (online adj social adj network*) or customi$ation or

(social adj connectivity) or (social adj5 network) or (social adj media) or (online adj5 communit*) or

(chat adj counsel*)).mp,hw.

(social adj bookmark*) or (social adj technolog*) or (social adj networking adj site*).mp,hw.

tailor* or personali* or relevan* or individuali* or feedback or (personali$ed adj feedback).mp,hw.

Gamification or (gam* adj strateg*) or (gam* adj design).mp,hw.

Incentive* or reinforcement* or reward*.mp,hw.

(goal adj setting).mp,hw.

monitor*.mp,hw.

(leader adj board) or (leaderboard) or (achievement adj badge*) or (progress adj report) or (progress

adj chart).mp,hw.

(persuasive adj design adj system*).mp,hw.

Usability.mp,hw.

Novelty.mp,hw.

Aesthetic*.mp,hw.

Medline RCT Filter - Cochrane

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

groups.ab.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8

exp animals/not humans.sh.

9 not 10

Appendix 2. Tools and techniques for narrative synthesis

| Developing a preliminary synthesis | Description of tool | Included in study | Detail of inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Textual description | Descriptive paragraph of study/intervention | Yes | Detailed description of each EPSs will be presented |

| Groupings and clusterings | Organising studies into manageable groups | Yes | Studies will be organised by EPS type as a means of synthesising the EPS results |

| Tabulation | Visual presentation of qualitative and quantitative data | Yes | Study results and characteristics will be tabulated |

| Transforming data into a common rubric | Data transformed into common rubric, for example, odds ratio for a meta-analysis | No | This is not possible as outcome and EPS types are too heterogeneous to include in a meta-analysis |

| Vote counting as a descriptive tool | Calculating frequencies of different results across different studies | Yes | Statistically significant results will be counted for an overview of effect. Quality of studies will be considered. This will be completed as a tool for exploring relationships (see below) |

| Translating data: thematic analysis | Translating the data into common themes across studies | No | More appropriate for qualitative data |

| Translating data: content analysis | Translating data into frequencies based on coding rules | No | More appropriate for qualitative data |

| Graphs, frequency distributions, funnel plots, forest plots and L’Abbe plots | Graphically present relationships within and between studies | No | Quantitative data not being used |

| Moderator variables and sub-group analyses | Examining characteristics between and within studies to explain variability in primary results | Yes | Variations between the EPS features will be examined. Populations, motivations to quit/reduce will be discussed. A table showing the EPS components of the evaluated interventions will be included |

| Idea webbing and concept mapping | Create visual models to conceptualise and explore connections across studies | No | Connections across studies will be explored with textual descriptions |

| Translation as an approach to exploring relationships85 | Using qualitative research techniques to synthesise findings from multiple studies | No | More appropriate for qualitative data |

| Qualitative case description86 | Use of descriptive data to explain differences in statistical findings | Yes | Will be used in conjunction with textual descriptions to explore the data |

| Investigator and methodological triangulation87 | Analysing data in relation to the context in which it was produced, for example, the disciplinary perspectives and expertise of the researchers | No | More appropriate for qualitative data |

Appendix 3. Quality rating of included studies

| Study | Adequate sequence generation | Adequate concealment | Adequate blinding of participants and personnel | Adequate blinding of engagement outcome | Incomplete engagement outcome data addressed | Free of selective reporting | Free of other bias | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elfeddali et al. 2012 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | No | 4/7 |

| Danaher et al. 2012 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | No | 4/7 |

| Houston et al. 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | 6/7 |

| Lieberman et al. 2006 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | No | 2/7 |

| McClure et al. 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | 5/7 |

| Munoz et al. 2009 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | 4/7 |

| Ramo et al. 2015 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | 2/3 |

| Schaub et al. 2015 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | 4/7 |

| Schulz et al. 2013 | Unclear | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | 2/7 |

| Severson et al. 2008 | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | 2/7 |

| Stanczyk et al. 2013 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | No | 3/7 |

| Strecher et al. 2008 | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 5/7 |

| Stoddard et al. 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 6/7 |

| Stoops et al. 2009 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | 3/7 |

| Tensil et al. 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | 5/7 |

Contributorship