Abstract

Introduction:

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block is now a well-established technique in post-operative analgesia for lower abdominal surgeries. We evaluated the effect of ultrasound-guided TAP block on recovery parameters in patients undergoing endoscopic repair of abdominal wall hernia.

Methods:

Thirty adults were randomised to receive either ropivacaine with dexmedetomidine (TR) or saline (TP) in TAP block, before emergence from anaesthesia. The patients were assessed for pain relief, sedation, time to ambulate (TA), discharge readiness (DR), postoperative opioid requirement and any adverse events.

Results:

The median visual analogue scale pain score of the study group (TR) and the control group (TP) showed a significant difference at all time points. TA was 5.3 ± 0.5 (TR) versus 7.4 ± 0.8 (TP), P < 0.001 and DR was 7.5 ± 0.9 (TR) versus 8.9 ± 0.6 (TP), P < 0.001 in hours. No adverse events were observed in any group.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrates that TAP block is a feasible option for pain relief following endoscopic repair of abdominal wall hernias. It produces markedly improved pain scores and promotes early ambulation leading to greater patient satisfaction and earlier discharge.

Keywords: Abdominal wall hernia, ambulate, anaesthesia, discharge, endoscopic, pain relief, transversus abdominis plane, transversus abdominis plane block, ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block has emerged as a safe, reliable and efficient technique to provide post-operative analgesia for a range of abdominal procedures and has been shown to minimise the usage of opioids in the perioperative period.[1,2,3,4,5] The application of TAP block for post-operative pain management of abdominal wall hernias has not been explored in any clinical trial.

This study was designed to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of TAP block in patients undergoing endoscopic repair of abdominal wall hernia under general anaesthesia[6,7] and its effect on the recovery parameters.

We hypothesised that performing TAP block has favourable recovery characteristics in patients undergoing endoscopic abdominal wall hernia repair under general anaesthesia.

The primary outcome of the study was time to ambulate (TA), whereas the secondary outcomes were the visual analogue scale (VAS) score, requirement for narcotic, discharge readiness (DR) and any adverse events.

METHODS

With the approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee, thirty adult patients of either gender scheduled for elective endoscopic repair of abdominal wall hernia were recruited to undergo this randomised prospective, double-blind study. Patients with any history suggestive of coronary artery disease, heart block, bradycardia, allergy to dexmedetomidine and propofol were excluded from the study.

Randomisation followed a computer-generated allocation schedule (R version 2.12), using allocation concealment to prevent prior knowledge of treatment assignment.

Numbers were assigned in strict chronological sequence, and study participants were entered in sequence. Each study patient was allocated a unique randomisation number on successful completion of screening, to be assigned to receive either one of the intervention groups (ropivacaine with dexmedetomidine: group-TR or saline TAP: group-TP), where only normal saline was used. The randomisation code was sent to the investigator (or designee) who decided the treatments according to the randomisation code.

To minimise bias and confounders, the decision to accept or reject a patient was made using inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Informed consent was obtained from participants before obtaining the randomisation code. Independent anaesthesiologists assessed the eligibility of the patient and obtained the randomisation number and allocation of treatment type. The codes were revealed to the researchers once the recruitment; data collection and analysis were completed. This study was conducted in compliance with good clinical practice (GCP) and the Indian GCP guidelines and in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki Guidelines for Ethics in Research. The study was registered with CTRI; CTRI/2012/12/003245.

General anaesthesia was standardised for all patients. Following induction with propofol 1–2 mg/kg, midazolam and fentanyl 2 μg/kg, airway was facilitated using atracurium besylate 0.5 mg/kg of ideal body weight. Anaesthesia was maintained on air in sevoflurane. Intraoperatively, all patients received diclofenac 75 mg and 1 g of paracetamol intravenously 1 h before expected time of conclusion of surgery.

At the end of surgery, after closure of ports, with the patient placed supine, TAP block was performed under all aseptic precautions using Sonosite M-Turbo machine, with linear array probe L38 (5–10 MHz). Muscle layers were identified in the midaxillary line, and using 22 G, 80 mm, SonoPlex cannula (Pajunk) was used for performing the block. The layers were first confirmed with hydrodissection using 5 ml of normal saline. Following this, the local anaesthetic was deposited in the fascial layer between transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles. The patients of group TR received bilateral TAP block using 20 ml of 0.375% ropivacaine with a total dexmedetomidine 0.5 ug/kg of ideal body weight, whereas patients of group TP received 20 ml of normal saline only, on each side. The anaesthesiologist drawing the drugs for TAP block was not involved in the study. The patients, their anaesthesiologists and the staff providing post-operative care were blinded to group allocation. The post-operative analgesia included paracetamol 1 g every 6 h and diclofenac 75 mg every 8 h at predetermined schedule. Tramazac hydrochloride (TMZ) was used as rescue analgesic in patients having VAS >4. All patients received intravenous ondansetron 4 mg, intraoperatively.

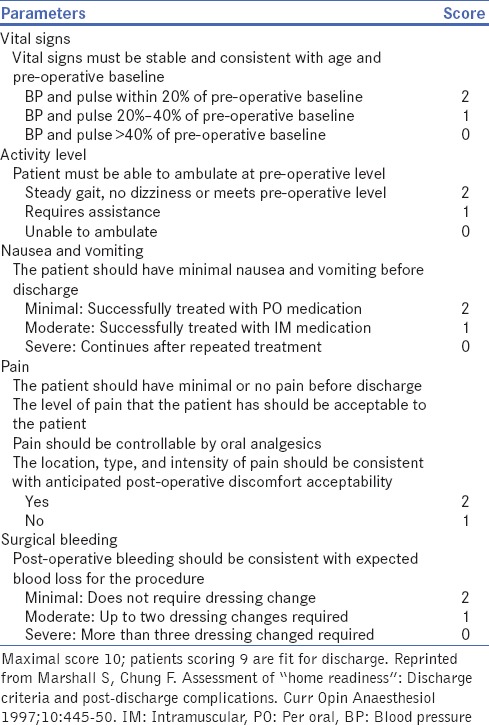

In the post-operative anaesthesia care unit (PACU), the pain scores were assessed using a numeric scale (VAS) and graded from 1 to 10, at rest and on movement. The readings were taken on arrival in PACU at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. DR and recovery parameters were based on criteria as shown in Table 1.[8,9] Any adverse events were recorded. Based on the results of a pilot study, our statistician calculated that minimum 15 participants would be needed in each group to achieve 96% power at 1% level of significance. Hence, thirty eligible participants were recruited for this study.

Table 1.

Post-anaesthesia discharge scoring system for determining home-readiness

Treatment code was not broken for the planned analysis of data until all decisions on the evaluability of the data from each individual patient had been made and documented. The evaluation of blinded and/or unblinded data analysis was done by in-house biostatistician.

Descriptive statistical methods were used to summarise the data, with hypothesis testing performed for the outcome variable. Discrete variables are reported as proportions and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation if normally distributed or as a median and interquartile range if not. Continuous data were analysed using two-sample t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test as appropriate. Categorical data were analysed using Chi-square analysis or Fisher's exact test where applicable. All statistical testing were two-sided and were performed using a significance (alpha) level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted with the STATA System, version 9.0 and R2.13.2.

RESULTS

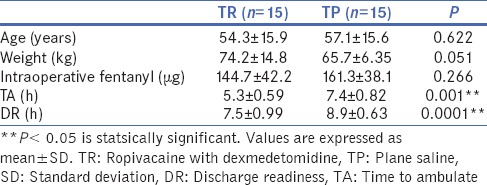

All of the thirty enrolled patients successfully completed the study and were perceived as successful TAP blocks with no protocol violations. The patient characteristics, duration of anaesthesia and intraoperative analgesic requirement were comparable amongst the two study groups [Table 2]. There difference between the groups with respect to the duration of surgery and intraoperative requirement of analgesics was not significant. The usage of TAP block significantly reduced the TA and DR [Table 3].

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and recovery parameters

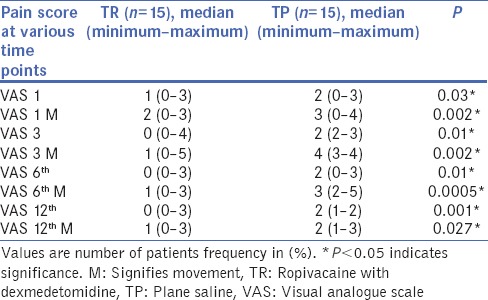

Table 3.

Pain assessment using visual analogue scale shows significant difference between the two groups at all time points

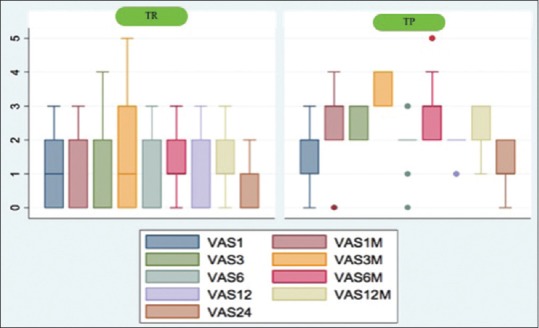

Even though the rescue analgesic requirement of the two groups did not differ much, there was a significant difference in the pain scores on movement. This possibly reflected in the TA and DR. Postoperatively, the median VAS pain score of the study group (TR) and the control group (TP) showed a significant difference at all time points. This could be appreciated more on movement and attempts to ambulate. Even though most patients remained comfortable and pain free with VAS <4 [Figure 1]. A number of patients requiring TMZ in the PACU did not differ between the groups.

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients between TR and TP groups shows higher number of patients with scores >4 in the TR group (more so on movement). However, most patients in TR group maintain consistently lower scores at rest as well as movement. TR is ropivacaine with dexmedetomidine; TP is plane saline, M signifies movement. X-axis is time points and Y-axis is visual analogue score

The benefits of the TAP block were reflected in significant statistical difference in the TA and DR. Inclusion of TAP block would be of particular benefit for reducing the hospital stay.

No adverse events related to the procedure or the drugs were observed. There was no incidence of post-operative nausea and vomiting or any difficulty in initiation of micturition in patients of either group; all patients started taking clear liquids and solids in comparable time.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that, with ultrasound-guided TAP block, the TA and the DR could be markedly reduced in adult patients undergoing endoscopic repair of abdominal wall hernia. We could not find any other study demonstrating its usefulness in patients undergoing these surgeries.

The goal of pain management in a post-operative patient is to provide effective pain relief, to improve the perioperative outcome by promoting early ambulation and minimising opioid-related complications and to promote patient satisfaction. The current trends and evidence support the use of the multimodal approach and context-sensitive pain management as the most effective strategy to achieve optimal pain management. Poorly controlled post-surgical pain can lower the level of patients' satisfaction, delay their recovery and increase the costs of stay in hospital.

Its technical simplicity, widespread effect, long duration of action, minimal contraindications and side-effects are the reasons for its ever-increasing popularity.

The innervation of the abdominal wall is derived from anterior divisions of spinal segmental nerves. These nerves run laterally between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscle layers of the abdominal wall. The TAP can be approached through the triangle of Petit. It can be performed as a blind technique or with the help of ultrasound guidance.

Even though the TAP block has gained popularity in pain management for abdominal surgeries, there is minimal documentation in the post-operative pain experience more so for endoscopic repair of abdominal wall hernias. The use of fixation devices such as tacks has been proposed to contribute significantly to post-operative pain. This may contribute to increased requirement of narcotic analgesia, which may further and delay recovery.[10,11,12,13]

It has been suggested that analgesia provided by TAP block might be comparable and even superior to that provided by opioids.[14,15,16] Ever since its introduction, the TAP block has been gaining wider acceptance and popularity. Several modifications have been suggested from time to time. Our study demonstrates that pain relief by TAP block is satisfactory at rest and on movement. The analgesia by the TAP block can be further enhanced by addition of adjuvants to the local anaesthetic.

Numerous clinical reports have described the use of dexmedetomidine, a federal drug administration approved drug. It is a specific α2-adrenergic receptor agonist with antinociceptive and sedative properties, as an adjuvant to local anaesthetics.[16,17,18,19,20] There have been multiple encouraging reports of application of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant for various nerve blocks, in adults as well as children.[4,16]

It was remarkable to note that the patients who received plane saline experienced considerable deterioration in the VAS scores on movement and attempts at ambulation. As a result, possibly there was a significant difference in the TA and the DR between the study and control groups.

CONCLUSION

Recovery is a continuous process and continues even after patient's discharge. In most cases, the discharge is delayed because of uncontrolled pain, vomiting and significant alterations in haemodynamics or unsteady gait. There was no instance of any such event in any patient group. Use of antiemetic medication and minimal requirement of opioids in the post-operative period could have prevented any incidence of nausea and vomiting. Moreover, with the described anaesthetic techniques, the DR as assessed using the post-anaesthesia DR scoring system [Table 1], showed remarkable improvement with the use of TAP block. This study also demonstrates that TAP block is efficacious as a part of multimodal analgesic technique and a feasible option for post-operative pain relief following endoscopic repair of abdominal wall hernia. Moreover, it also demonstrates improved pain scores, early ambulation, greater patient satisfaction and earlier discharge.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lange H, Kranke P, Steffen P, Steinfeldt T, Wulf H, Eberhart LH. Combined analgesics for postoperative pain therapy. Review of effectivity and side-effects. Anaesthesist. 2007;56:1001–16. doi: 10.1007/s00101-007-1232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niraj G, Searle A, Mathews M, Misra V, Baban M, Kiani S, et al. Analgesic efficacy of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block in patients undergoing open appendicectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:601–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukhtar K, Khattak I. Transversus abdominis block for renal transplant recipient. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:663–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carney J, Finnerty O, Rauf J, Curley G, McDonnell JG, Laffey JG. Ipsilateral transversus abdominis plane block provides effective analgesia after appendecto- my in children: A randomised controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:998–1003. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ee7bba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carney J, McDonnell JG, Ochana A, Bhinder R, Laffey JG. The transversus abdominis plane block provides effective postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:2056–60. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181871313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obayah GM, Refaie A, Aboushanab O, Ibraheem N, Abdelazees M. Addition of dexmedetomidine to bupivacaine for greater palatine nerve block prolongs postoperative analgesia after cleft palate repair. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:280–4. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283347c15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ammar AS, Mahmoud KM. Ultrasound-guided single injection infraclavicular brachial plexus block using bupivacaine alone or combined with dexmedetomidine for pain control in upper limb surgery: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Saudi J Anaesth. 2012;6:109–14. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.97021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung F, Chan V, Ong D. A postanesthetic discharge scoring system for home readiness after ambulatory surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:500–6. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(95)00130-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steward DJ, Volgyesi G. Stabilometry: A new tool for measuring recovery following general anaesthesia. Can Anesth Soc J. 1978;25:4–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03006775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PM, Ross S, Grant AM. EU Hernia Trialists Collaboration. Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD001785. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tolver MA, Rosenberg J, Bisgaard T. Early pain after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. A qualitative systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:549–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch CA, Greenlee SM, Larson DR, Harrington JR, Farley DR. Randomized prospective study of totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: Fixation versus no fixation of mesh. JSLS. 2006;10:457–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau H, Patil NG. Acute pain after endoscopic totally extraperitoneal (TEP) inguinal hernioplasty: Multivariate analysis of predictive factors. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:92–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9068-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonnell JG, O'Donnell B, Curley G, Heffernan A, Power C, Laffey JG. The analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block after abdominal surgery: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:193–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000250223.49963.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randall IM, Costello J, Carvalho JC. Transversus abdominis plane block in a patient with debilitating pain from an abdominal wall hematoma following cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 2008;10:1928. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318170baf3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Hennawy AM, Abd-Elwahab AM, Abd-Elmaksoud AM, El-Ozairy HS, Boulis SR. Addition of clonidine or dexmedetomidine to bupivacaine prolongs caudal analgesia in children. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:268–74. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pöpping DM, Elia N, Marret E, Wenk M, Tramèr MR. Clonidine as an adjuvant to local anesthetics for peripheral nerve and plexus blocks: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:406–15. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebert TJ, Hall JE, Barney JA, Uhrich TD, Colinco MD. The effects of increasing plasma concentrations of dexmedetomidine in humans. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:382–94. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200008000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshitomi T, Kohjitani A, Maeda S, Higuchi H, Shimada M, Miyawaki T. Dexmedetomidine enhances the local anesthetic action of lidocaine via an alpha-2A adrenoceptor. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:96–101. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318176be73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brummett CM, Norat MA, Palmisano JM, Lydic R. Perineural administration of dexmedetomidine in combination with bupivacaine enhances sensory and motor blockade in sciatic nerve block without inducing neurotoxicity in rat. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:502–11. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318182c26b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]