Developmental defects caused by the accumulation of hydroxy-fatty acid in seed are reduced by the expression of castor acyltransferases.

Abstract

Researchers have long endeavored to produce modified fatty acids in easily managed crop plants where they are not natively found. An important step toward this goal has been the biosynthesis of these valuable products in model oilseeds. The successful production of such fatty acids has revealed barriers to the broad application of this technology, including low seed oil and low proportion of the introduced fatty acid and reduced seed vigor. Here, we analyze the impact of producing hydroxy-fatty acids on seedling development. We show that germinating seeds of a hydroxy-fatty acid-accumulating Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) line produce chlorotic cotyledons and suffer reduced photosynthetic capacity. These seedlings retain hydroxy-fatty acids in polar lipids, including chloroplast lipids, and exhibit decreased fatty acid synthesis. Triacylglycerol mobilization in seedling development also is reduced, especially for lipids that include hydroxy-fatty acid moieties. These developmental defects are ameliorated by increased flux of hydroxy-fatty acids into seed triacylglycerol created through the expression of either castor (Ricinus communis) acyltransferase enzyme ACYL-COA:DIACYLGLYCEROL ACYLTRANSFERASE2 or PHOSPHOLIPID:DIACYLGLYCEROL ACYLTRANSFERASE1A. Such expression increases both the level of total stored triacylglycerol and the rate at which it is mobilized, fueling fatty acid synthesis and restoring photosynthetic capacity. Our results suggest that further improvements in seedling development may require the specific mobilization of triacylglycerol-containing hydroxy-fatty acids. Understanding the defects in early development caused by the accumulation of modified fatty acids and providing mechanisms to circumvent these defects are vital steps in the development of tailored oil crops.

Plants are an extremely important source of oils for both food and industrial uses. The most valuable oils are produced in seeds, in the form of triacylglycerol (TAG) molecules that are composed of glycerol backbones with fatty acids (FA) attached through acyl bonds. In edible oils, most FA are 16- and 18-carbon chains, often with double bonds distributed throughout. Oils used in industry are similar, but certain plants also produce modified FA that exhibit uncommon chain lengths, carbon-carbon double bond locations, or side groups. These diverse structures make several modified FA quite valuable, contributing to multibillion dollar industries (Dyer et al., 2008). Unfortunately, most high-value modified FA are found in the oil of plants with limited capacity for agronomic exploitation. Ricinoleic acid (Δ-12-hydroxy-9-cis-octadecanoic acid), for example, is produced in the seed endosperm of castor (Ricinus communis), where it constitutes 90% of the total oil. The large-scale industrial cultivation of castor to produce this hydroxy-fatty acid (HFA) is limited by its confinement to tropical climates. In addition, harvesting and processing castor is dangerous work, as the seeds contain powerful allergens and the toxin ricin (Severino et al., 2012). As biochemical understanding of the pathways of lipid synthesis in nonmodel species has improved, researchers have explored biotechnological options for producing oil with high levels of HFA or other modified FA in crops more amenable to temperate agriculture.

The production of ricinoleic acid in castor occurs via the hydroxylation of oleic acid (18:1), which is esterified to the sn-2 position of phosphatidylcholine (PC) by the enzyme FATTY ACID HYDROXYLASE12 (RcFAH12; Bafor et al., 1991). When RcFAH12 was expressed in the seeds of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), a mixture of 18- and 20-carbon HFA was produced (Kumar et al., 2006). To increase substrate for the hydroxylation reaction, RcFAH12 was expressed in the Arabidopsis fatty acid elongation1 (fae1) mutant, which fails to elongate 18- to 20-carbon FA, producing seeds with elevated 18:1 (Kunst et al., 1992). This work resulted in the creation of lines like CL37, which accumulate HFA to 17% of the total seed oil (Lu et al., 2006). In these model Arabidopsis lines, not only is the proportion of HFA in the total seed oil much lower than that of the current source of HFA, but the amount of total oil produced in each seed is greatly reduced. Each of these issues bodes ill for the successful transfer of the technology to other temperate oilseed crops.

The low oil content has been addressed directly using transgenic experiments where HFA-accumulating Arabidopsis either overexpresses a transcriptional regulator of seed development (Adhikari et al., 2016) or increases lipid droplet size (Lunn et al., 2018), each of which modestly improves the amount of oil in those seeds. The second problem of low HFA proportion has been addressed principally by the coexpression of castor TAG biosynthesis enzymes that have coevolved with RcFAH12 (Burgal et al., 2008; van Erp et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2012), on the hypothesis that these enzymes would exhibit substrate preference in the synthesis of lipids containing HFA. Two lines incorporating this strategy are CL7:RcDGAT2 (DG2; Burgal et al., 2008) and CL37:RcPDA1A (PD1a; van Erp et al., 2011). Line DG2 coexpresses castor ACYL-COA:DIACYLGLYCEROL ACYLTRANSFERASE2 (RcDGAT2), which produces TAG by the incorporation of an acyl substrate from the intracellular acyl-CoA pool onto the sn-3 position of diacylglycerol. The PD1a line coexpresses the castor PHOSPHATIDYLCHOLINE:DIACYLGLYCEROL ACYLTRANSFERASE1A (RcPDAT1A), which also synthesizes TAG by the incorporation of an acyl group onto the sn-3 position of diacylglycerol, but in this case the acyl group is transferred from the sn-2 position of a PC molecule. Coexpression of either of these enzymes increases the HFA proportion from 17% to about 24% of the total seed oil (Burgal et al., 2008; van Erp et al., 2011). Interestingly, increasing the flux of HFA into TAG in these lines also partially restores total oil levels to those of their parent. Furthermore, coexpression of these acyltransferase genes in lines engineered for reduced expression of the orthologous Arabidopsis genes produces an additional increase in the proportion of HFA incorporated into TAG, reaching a maximum accumulation of 31% of the total oil (van Erp et al., 2015). Unfortunately, however, this level is still less than the expected requirement for commercial exploitation (Cahoon et al., 2006).

Reduced seed vigor is a third significant barrier to the commercial development of crops accumulating nonnative FA. When seeds germinate, their metabolism is heterotrophic before the seedlings achieve photoautotrophic growth. The source of energy sustaining early growth is the consumption of FA derived from TAG through β-oxidation, producing acetyl-CoA to be metabolized by the glyoxylate cycle (Chapman et al., 2012). Alteration of seeds producing common FA often leads to the loss of reproductive vigor, although the impact of modified FA on reproduction has not been examined in detail. Reduced germination and establishment has been reported in Arabidopsis seeds producing conjugated (Cahoon et al., 2006) and epoxidated (Li et al., 2012) FA. Poor germination has been reported in Arabidopsis and camelina (Camelina sativa) accumulating HFA (Snapp et al., 2014; Adhikari et al., 2016), a defect somewhat ameliorated by the addition of Suc (Lunn et al., 2018). Although Suc is the preferred substrate for utilization during postgerminative growth, it inhibits the breakdown of storage lipids, making interpretation of these results more difficult (Pinfield-Wells et al., 2005). The limited information available about germination and establishment highlights the need for a detailed analysis of the impact that modified FA production has on these nonnative species during early development, which is a critical step in transferring the production of these valuable FA to economically practicable crop species.

In this report, we examine the impact of seed-specific HFA accumulation on germination and seedling establishment using a well-characterized Arabidopsis line to model these processes in developing oilseeds. We show that line CL37 achieves parental levels of radicle emergence but often fails to establish a new plant, atrophying in its transition to photoautotrophic growth. We determine that reduced levels of polar lipids lead to reduced photosynthetic capacity and demonstrate that TAG molecules containing HFA moieties are more slowly mobilized than those without HFA components. Finally, we show that the use of castor enzymes to increase the flux of HFA into TAG both decreases the contamination of polar lipid fractions by HFA and increases lipid mobilization, largely recovering seedling establishment.

RESULTS

Defective Seedling Establishment of Arabidopsis Accumulating HFA Is Partially Recovered by Castor Acyltransferases

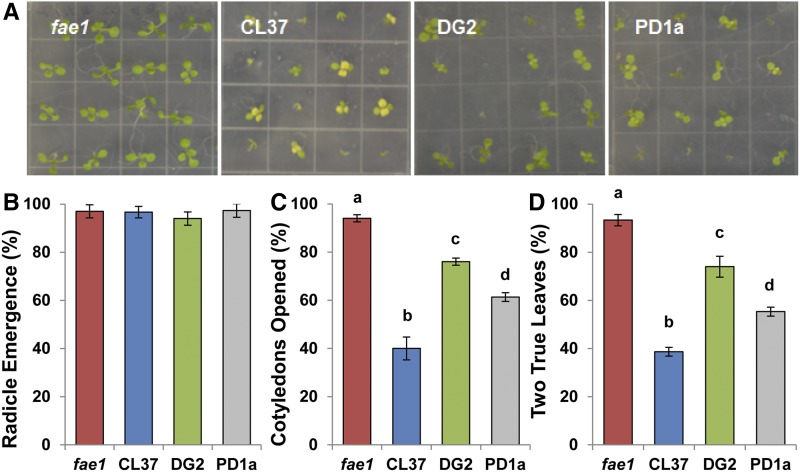

Arabidopsis line CL37, which accumulates HFA to about 17% of its total seed oil, is defective in reproduction (Lunn et al., 2018). We quantified this reproductive defect by measuring the proportion of plants that survived to three developmental stages. We compared CL37 (Lu et al., 2006) with its parent fae1 (Kunst et al., 1992), which does not accumulate HFA, as well as with lines that coexpress castor acyltransferases with RcFAH12 in their seed: DG2 (Burgal et al., 2008) and PD1a (van Erp et al., 2011). Seed samples were sown on agar plates without Suc and scored for the proportion of seeds attaining radicle emergence at 1 d after stratification (DAS), fully opened cotyledons at 4 DAS, and seedlings with two true leaves at 10 DAS, at which point the plates were photographed. Compared with its fae1 parent, fully opened cotyledons of CL37 were chlorotic and few seeds successfully established seedlings at 10 DAS (Fig. 1A). In contrast, all seedlings that opened cotyledons in DG2 and PD1a were green and healthy. Average radicle emergence for fae1 seed was 97% ± 2.73% (sd), and the other lines were similarly successful (Fig. 1B). The proportion of fae1 seedlings that displayed fully opened cotyledons at 4 DAS was 94% ± 1.4%. CL37 was significantly (P = 0.001, ANOVA) different at this stage, with only 40% ± 4.71% open cotyledons, a reduction of 2.3-fold compared with the fae1 parent. Both DG2 and PD1a were significantly more successful than CL37 at continuing development (Fig. 1C). For line DG2, 76% ± 1.49% of the seeds reached this stage, and for PD1a, 61.3% ± 1.82% produced open cotyledons, 1.9- and 1.5-fold more than CL37, respectively. The DG2 seeds were more successful than PD1a at this stage by 1.2-fold. By 10 DAS, fae1 seeds produced 93.3% ± 2.35% seedlings with two true leaves, while only 33% ± 2.73% of CL37 seeds produced such leaves, a 2.8-fold decrease from its parent (Fig. 1D). The proportions of seeds producing two true leaves from DG2 and PD1a were 74% ± 4.34% and 55.3% ± 1.82%, respectively, with DG2 having, on average, 1.3-fold greater success than PD1a. These experiments show that CL37 is severely restricted in its reproductive development compared with its non-HFA-expressing fae1 parent, but the defect is partly relieved in lines coexpressing a castor acyltransferase, DG2 and PD1a. For each HFA-accumulating line, radicle emergence was successful, but many seedlings of each transgenic line then cease development. Seedlings that produce fully opened cotyledons almost uniformly produce two true leaves, indicating that the development of these hydroxylase-expressing lines arrests after radicle emergence but before full opening of the cotyledons.

Figure 1.

Early development of fae1, CL37, DG2, and PD1a. A, Representative images of seedlings at 10 DAS. B, Proportion of seedlings with an emerged radicle at 1 DAS. C, Proportion of seedlings with fully opened cotyledons at 4 DAS. D, Proportion of seedlings with two true leaves of 1 mm at 10 DAS. Colors denote fae1 (red), CL37 (blue), DG2 (green), and PD1a (gray). Values indicate means ± SD; n = 5 independent replicates of 30 seeds. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA (P < 0.001) with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Columns with different letters are statistically different.

Postgerminative CL37 Has Low Chlorophyll and Reduced Photosynthetic Activity

The chlorosis of CL37 cotyledons (Fig. 1A) resembles phenotypes observed in our laboratory resulting from impaired photosynthetic capacity (McConn and Browse, 1998; Barkan et al., 2006). To measure the chlorophyll content of these hydroxylase lines, 30 seeds from each line were sown on five independent occasions and cultivated for 10 d of growth under 100 µmol m−2 s−1 continuous white light at 22°C, followed by chlorophyll extraction from weighed whole seedlings. The chlorophyll content in fae1 was 1.02 ± 0.06 μg g−1 fresh weight, while CL37 averaged significantly (P = 0.0001, Student’s t test) less at 0.62 ± 0.06 μg g−1, a 1.6-fold reduction (Table I). Both DG2 and PD1a were statistically similar to fae1 at 1.09 ± 0.07 and 1.03 ± 0.01 μg g−1, respectively. We also measured the chlorophyll a/b ratio to assess the proportion of light-harvesting complexes to reaction centers. The average chlorophyll a/b ratio of fae1 was 2.66 ± 0.17, and no significant differences were measured among the test lines (Table I). These data show a reduction in the synthesis and maintenance of functional photosystems in CL37 but no impact on the ratio of reaction centers to light-harvesting complexes.

Table I. Photochemical capacity of hydroxylase-expressing Arabidopsis.

Values indicate means ± sd; n = 3 independent replicates of 30 seeds.

| Photosynthetic Measurement | fae1 | CL37 | DG2 | PD1a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll (μg g−1) | 1.021 ± 0.06 | 0.620 ± 0.06 | 1.092 ± 0.07 | 1.038 ± 0.01 |

| Chlorophyll a/b ratio | 2.667 ± 0.17 | 2.497 ± 0.17 | 2.653 ± 0.17 | 2.522 ± 0.21 |

| Fv/Fm | 0.728 ± 0.04 | 0.759 ± 0.05 | 0.742 ± 0.08 | 0.721 ± 0.10 |

| ФPSII | 0.638 ± 0.06 | 0.231 ± 0.05 | 0.634 ± 0.06 | 0.619 ± 0.04 |

A reduction in chlorophyll content suggests that CL37 is defective in its transition to photoautotrophic growth. To determine the competence of the photosystems, we measured the potential quantum efficiency of PSII using Fv/Fm in dark conditions. A total of three independent replicate plates of 30 plants were sown and stratified for 2 d before a 10-d growth period and measurement of Fv/Fm. For fae1, Fv/Fm averaged 0.72 ± 0.04, with none of the test lines significantly different (Table I). However, we did see differences when we measured ФPSII, which quantifies the steady-state quantum efficiency under illuminated conditions. Three independent replicates of plates containing seeds were grown for 10 d. The ФPSII value of fae1 was 0.63 ± 0.06, but the values for CL37 averaged 0.23 ± 0.05, a 2.7-fold reduction (P = 0.0001, Student’s t test). While there was no significant difference between fae1 and DG2, values of ФPSII in PD1a were reduced slightly compared with both fae1 and DG2, averaging 0.61 ± 0.04. The Fv/Fm data indicate that, in CL37, the reaction centers of PSII retain energy transduction, although the ФPSII values indicate that overall photosynthetic capacity is reduced, while in DG2 and PD1a, this defect is ameliorated.

Reduced Total FA and HFA Containing Polar Lipid in DG2 and PD1a

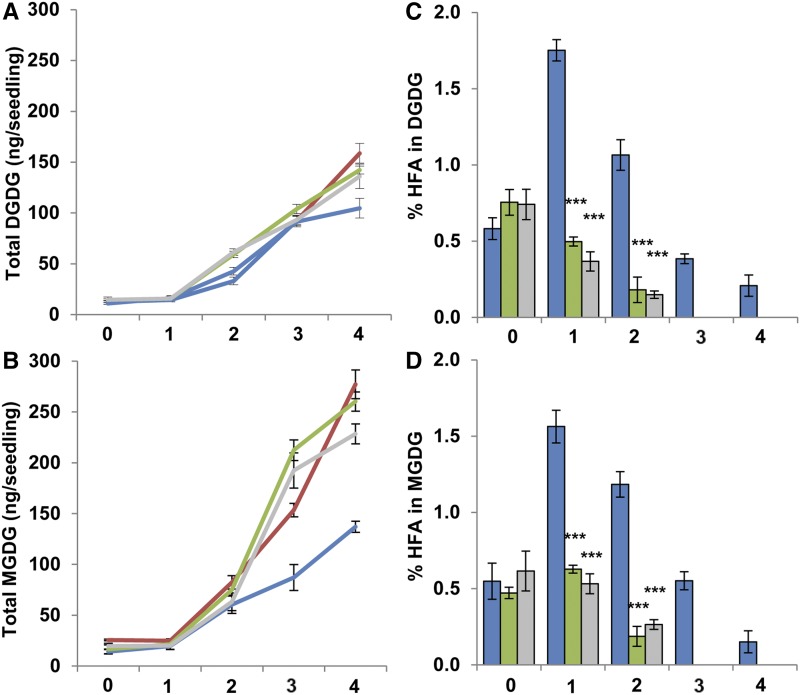

Since polar lipids are critical to the membrane structures that support photosynthesis, we examined these lipids by determining the absolute FA and HFA contents of monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG), digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), and PC in our experimental lines. We sowed seeds from each line on agar plates on three independent occasions, harvested the seedlings daily from 0 to 4 DAS, and then extracted the polar lipids to examine the transition from radicle emergence to fully opened cotyledons. Using thin-layer chromatography (TLC), we isolated the MGDG, DGDG, and PC lipid fractions, then quantified the HFA content of each by gas chromatography.

Chloroplast function is dependent on MGDG and DGDG, which combine to form 74% of the chloroplast lipid (Miquel and Browse, 1992). Analysis of the total MGDG and DGDG over time showed a rapid expansion of these lipids during early development. Levels of DGDG in fae1 increased from 12.57 ± 0.84 to 158.67 ± 9.69 ng seedling−1 over 4 d (Fig. 2A). CL37 showed significantly reduced DGDG, averaging 104.73 ± 6.29 ng seedling−1 at 4 DAS, a 1.5-fold reduction from the parental line. Both DG2 and PD1a were significantly higher than CL37 at 4 DAS, averaging 142.28 ± 3.91 and 136.10 ± 12.08 ng seedling−1, respectively, but were not equivalent to fae1. The amount of the most abundant chloroplast lipid, MGDG, also increased in fae1 over the time course, from 25.69 ± 0.86 to an average of 277.15 ± 14.07 ng seedling−1 at 4 DAS (Fig. 2B). Total MGDG at 4 DAS was less in CL37 than in fae1, averaging 136.99 ± 5.44 ng seedling−1. Both DG2 and PD1a were significantly higher in MGDG content than CL37, averaging 260.17 ± 9.35 and 228.36 ± 9.75 ng seedling−1, respectively, and the MGDG content of DG2 was similar to that of fae1 at 4 DAS. Analysis of HFA in chloroplast lipids among the transgenic lines demonstrated that they declined rapidly in the DG2 and PD1a lines, dropping below the detection limit by 3 DAS (Fig. 2, C and D). In contrast, MGDG- and DGDG-containing HFA increased in CL37 at 1 DAS from 0.54% ± 0.11% to 1.56% ± 0.1% and from 0.51% ± 0.07% to 1.75% ± 0.06%, respectively. The HFA proportions in both these chloroplast lipids then began to decline over time but persisted at detectable levels throughout the 4-d time course. Collectively, these data show both that CL37 has decreased amounts of MGDG and DGDG and that these same lipids retain measurable HFA at 4 DAS. Coexpression of the castor DGAT2 acyltransferase largely restores the levels of MGDG and DGDG to that of fae1. Coexpression of the castor PDAT also substantially recovers the accumulation of these lipids, but to a lesser extent than the expression of DGAT2. Both the DG2 and PD1a lines have proportionally less HFA in their chloroplast lipids than CL37 at this stage of development.

Figure 2.

Proportion of HFA in major chloroplast polar lipids during early development. Total DGDG (A), total MGDG (B), proportion of HFA in DGDG (C), and proportion of HFA in MGDG (D) are shown at 0 to 4 DAS. Colors denote fae1 (red), CL37 (blue), DG2 (green), and PD1a (gray). Values indicate means ± SD; n = 3 independent replicates of 90 seeds. Statistical analysis: Student’s t test. Values statistically different from CL37 are marked with asterisks (***, P < 0.001).

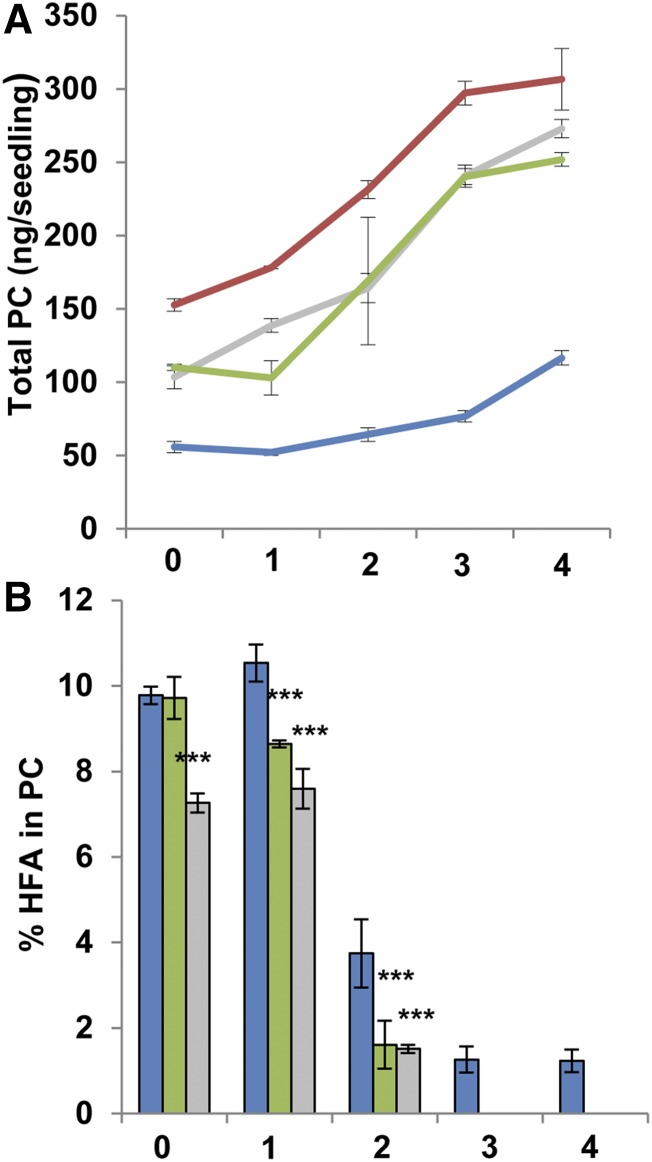

There also were differences in both the total amount of PC and the accumulation of HFA-PC. During the time course, fae1 accumulated a total of 306.62 ± 20.99 ng seedling−1 PC (Fig. 3A). This total was dramatically lower in CL37, with a maximum of 116.63 ± 4.86 ng seedling−1 by 4 DAS, a reduction of 2.6-fold compared with fae1. The total amount of PC was significantly higher in both the DG2 and PD1a lines compared with CL37, averaging 272.93 ± 6.3 and 251.91 ± 4.65 ng seedling−1, respectively. However, neither acyltransferase coexpression line recovered PC levels to the fae1 value. All three HFA-accumulating lines contained HFA-PC, which declined as a proportion of total oil over time (Fig. 3B). Throughout the time course, HFA levels in the PC of CL37 were significantly higher than those of the DG2 and PD1a lines. Notably, by 3 DAS, the HFA in the PC fraction of lines DG2 and PD1a fell below the detection limit of our analysis. In sharp contrast, the PC in CL37 still contained 1.44% ± 0.3% HFA even at 4 DAS, which was similar to the value found at 3 DAS. This analysis demonstrates not only that HFA-PC persists in this lipid for at least 4 d but that the total PC accumulation is reduced in CL37 compared with the parental line. In contrast, the presence of HFA-PC and the reduced quantity of PC present in CL37 are largely ameliorated in lines DG2 and PD1a.

Figure 3.

Proportion of HFA in PC during early development. Total PC (A) and proportion of HFA in PC (B) are shown at 0 to 4 DAS. Colors denote fae1 (red), CL37 (blue), DG2 (green), and PD1a (gray). Values indicate means ± SD; n = 3 independent replicates of 90 seeds. Statistical analysis: Student’s t test. Values statistically different from CL37 are marked with asterisks (***, P < 0.001).

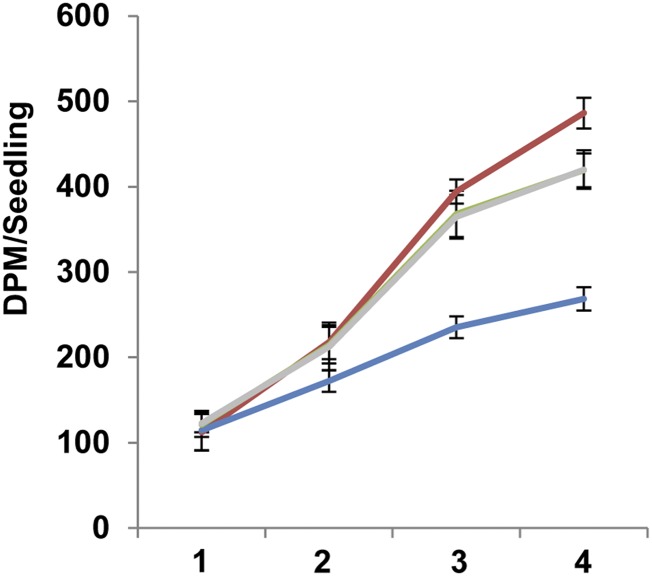

FA Synthesis during Establishment Is Reduced in CL37

Our data show that polar lipid is rapidly synthesized during early seedling development (Figs. 2 and 3), so it was surprising that HFA-PC levels of CL37 did not quickly fall below detectable levels. One explanation for both the presence of HFA and the low level of PC could be a partial failure of FA synthesis as the seedlings develop. To test this hypothesis, we measured the rate of FA synthesis from 1 to 4 DAS by labeling nascent FA with 3H incorporated from 3H2O during the reduction steps of FA synthesis (Jungas, 1968). On three independent occasions, 90 seedlings from fae1, CL37, DG2, and PD1a were grown on agar plates and transplanted onto medium containing 3H2O. The accumulation of 3H-labeled FA was measured after 1, 2, 3, and 4 d, then normalized against the number of seedlings (Fig. 4). The rate of FA synthesis at 1 DAS in fae1 averaged 112.11 ± 21.56 dpm seedling−1, and the other lines were similar. By 4 DAS, the synthesis rate of FA in fae1 increased to 486.17 ± 17.84 dpm seedling−1. The FA synthesis rate in CL37 seedlings was significantly lower, averaging 268.7 ± 13.72 dpm seedling−1, 1.8-fold less than the parental level. In DG2 and PD1a, FA synthesis averaged 419.17 ± 19.74 and 420 ± 22.59 dpm seedling−1, respectively, which were 1.5-fold increases above the CL37 level, albeit still lower than in the fae1 parent. This analysis reveals a lower rate of FA synthesis in CL37 compared with fae1, a defect that is significantly relieved in the DG2 and PD1a lines.

Figure 4.

Rate of FA synthesis during early development. The dpm of 3H2O normalized per seedling is shown at 1 to 4 DAS. Colors denote fae1 (red), CL37 (blue), DG2 (green), and PD1a (gray). The data for DG2 and PD1a are virtually identical, so the DG2 data are obscured by the PD1a data. Values indicate means ± SD; n = 3 independent replicates of 90 seeds.

Increased Mobilization of TAG in DG2 and PD1a

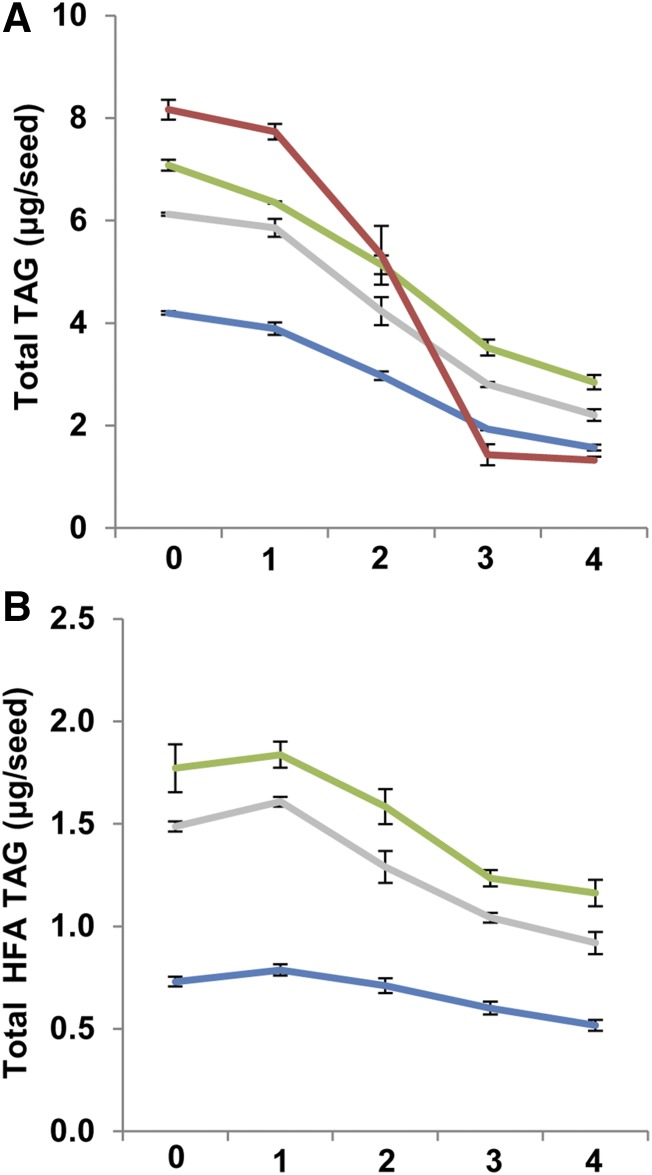

The reduced polar lipid synthesis suggests that the breakdown of neutral storage lipid might be different among the three HFA-containing lines, since storage lipids are used to provide energy for FA synthesis. To test this, we sowed seeds from fae1, CL37, DG2, and PD1a in three independent replicates on agar plates and extracted the neutral lipids at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 DAS. Bulk TAGs were separated by TLC and then collected for analysis by FA methyl ester derivatization and gas chromatography. At 0 DAS, fae1, CL37, DG2, and PD1a contained an average of 8.16 ± 0.19, 4.19 ± 0.03, 7.08 ± 0.1, and 6.12 ± 0.03 μg TAG seed−1, respectively (Fig. 5A). Over the 4-d time course, total TAG in fae1 fell by 6.84 μg seed−1, a 6.1-fold reduction. CL37 total TAG also fell during the time course, but only by 2.61 ± 0.06 μg seed−1, a 2.8-fold reduction and significantly less than that in fae1. TAG levels in PD1a fell by 3.91 ± 0.13 μg seed−1, and DG2 by 4.23 ± 0.18 μg seed−1, reductions of 2.7- and 2.4-fold relative to their 0-DAS value. When we determined the total HFA-TAG in each line, CL37 contained 0.73 ± 0.02 μg seed−1 at 0 DAS (Fig. 5B). The HFA-TAG in PD1a was 1.16 ± 0.06 μg seed−1, while DG2 contained 1.77 ± 0.11 μg seed−1, the highest level of the three lines. Over the time course, HFA-TAG in CL37 declined from 0 to 4 DAS by 0.214 ± 0.02 μg seed−1, a 1.4-fold reduction. Line PD1a dropped by 0.56 ± 0.05 μg seed−1 and DG2 by 0.6 ± 0.12 μg seed−1, 1.2- and 1.5-fold reductions, respectively. This lipid analysis shows that CL37 not only mobilizes much less TAG than fae1 but also that the rate of mobilization is slower. Interestingly, despite containing higher proportions of HFA, DG2 and PD1a have higher mobilization rates than CL37 both for common FA and for HFA-TAG moieties.

Figure 5.

TAG mobilization during early development. Total TAG (A) and total HFA content in TAG (B) are shown. Colors denote fae1 (red), CL37 (blue), DG2 (green), and PD1a (gray). Values indicate means ± sd; n = 3 independent replicates of 90 seeds.

HFA-Containing TAG Species Are Poorly Mobilized during Germination

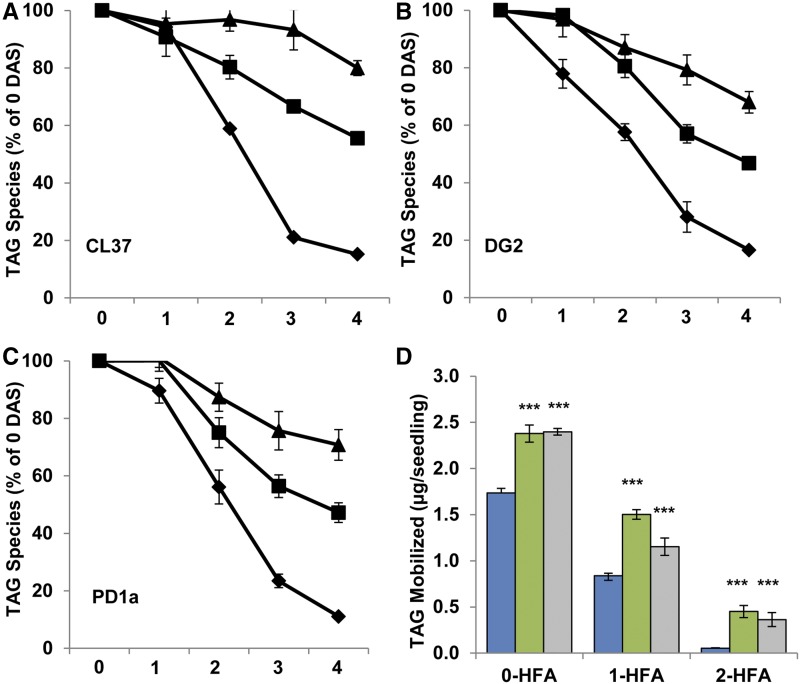

In CL37, DG2, and PD1a, the relative rate of HFA mobilization was reduced compared with that of the FA naturally found in Arabidopsis seeds. Since the initial step in mobilizing storage lipid is hydrolysis to diacylglycerol by a TAG lipase (Eastmond, 2006), we hypothesized that Arabidopsis enzymes might show substrate specificity in favor of TAG with no HFA moiety. We quantified the TAG species in CL37, DG2, and PD1a during development from 0 to 4 DAS. On three separate occasions, agar plates containing seeds for each line were sown and collected daily. Total lipid was extracted and separated by TLC to reveal three distinct TAG species: 2-, 1-, and 0-HFA-TAG; no 3-HFA-TAG was detected. The 2-, 1-, and 0-HFA-TAG bands were collected, and each fraction was analyzed individually by FA methyl ester derivatization. In all lines, 0-HFA-TAG was most rapidly and completely mobilized, averaging reductions of 84.81% ± 0.87%, 83.45% ± 0.74%, and 88.94% ± 0.67% for CL37, DG2, and PD1a, respectively (Fig. 6). However, differences in the mobilization of HFA-TAG species were evident throughout the time course. For CL37, 1-HFA-TAG at 4 DAS was reduced by 44.43% ± 1.76% and 2-HFA-TAG by 20.03% ± 2.59% of the 0-DAS value, representing 1.9- and 4.2-fold reductions, respectively, of the HFA-containing species (Fig. 6A). Line DG2 retained less of its original HFA-TAG than CL37, with 1-HFA-TAG reduced by 53.19% ± 1.74% and 2-HFA-TAG reduced by 31.99% ± 3.47% on average (Fig. 6B). A trend similar to that in DG2 was seen in the PD1a line, with reduction of 1-HFA-TAG by 52.79% ± 3.39% and 2-HFA-TAG by 29.23% ± 5.34% (Fig. 6C). This greater reduction of 1- and 2-HFA-TAG in both DG2 and PD1a compared with CL37 is particularly noteworthy. To further quantity the differences in HFA-TAG between lines, we calculated the total HFA-TAG mobilized. In DG2 and PD1a, the mobilization of 1-HFA-TAG was 1.5 ± 0.05 and 1.15 ± 0.09 µg seedling−1, which was higher than that in CL37 by 1.8- and 1.3-fold, respectively. Total 2-HFA-TAG in DG2 and PD1a mobilization was 0.45 ± 0.06 and 0.36 ± 0.07 µg seedling−1, respectively, which was 9- and 7.2-fold higher than in CL37. These data show that, in all lines, 0-HFA-TAG is preferentially mobilized compared with its HFA-containing counterparts, but DG2 and PD1a each break down HFA-TAG more readily than CL37.

Figure 6.

TAG species during early development. A to C, The percentage of each HFA TAG species remaining is compared with 0 DAS for CL37 (A), DG2 (B), and PD1a (C). Shapes denote 0-HFA (diamonds), 1-HFA (squares), and 2-HFA (triangles). D, Proportion of each species mobilized at 4 DAS. Colors denote CL37 (blue), DG2 (green), and PD1a (gray). Values indicate means ± sd; n = 3 independent replicates of 90 seeds. Statistical analysis: Student’s t test. Values statistically different from CL37 are marked with asterisks (***, P < 0.001).

Seedlings from HFA-Accumulating Seeds Have Reduced Hypocotyl Elongation and Soluble Sugar Levels

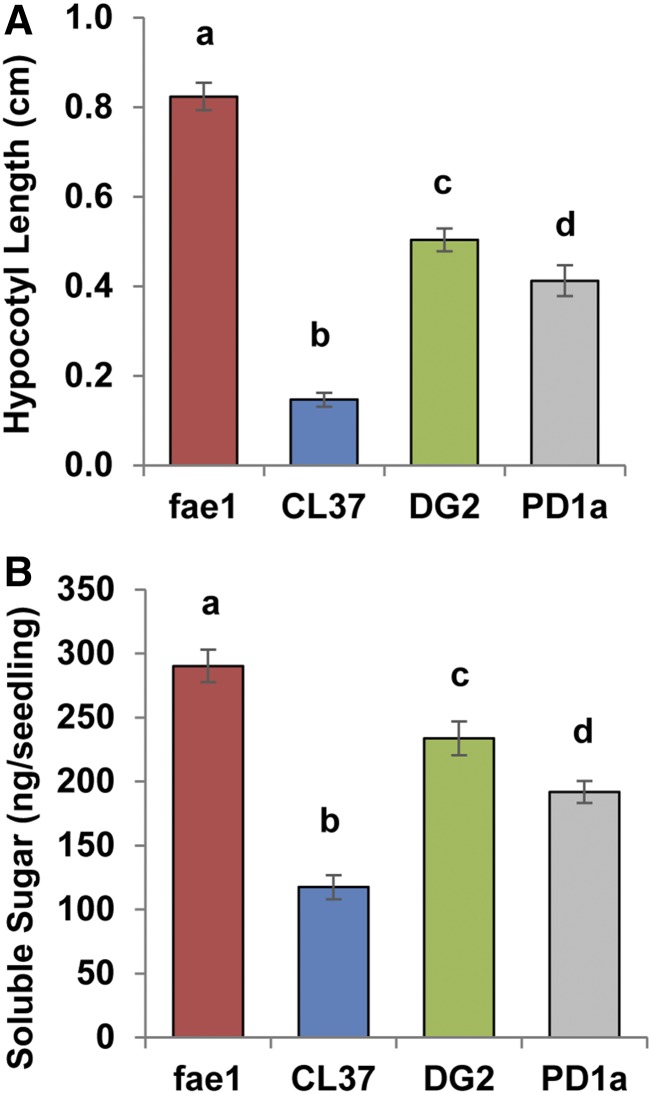

All HFA-containing lines were lower in both total and rates of HFA-TAG mobilization compared with TAG containing only common FA. Under the hypothesis that this would have a significant impact on seedlings grown in the dark, we measured hypocotyl elongation, which, without the support of photosynthesis, relies on carbon skeletons derived from the breakdown of storage oil. Samples from fae1, CL37, DG2, and PD1a were sown on 10 independent agar plates with three sets of seeds and incubated in the dark until 4 DAS, when the hypocotyl lengths were measured (Fig. 7A). The average hypocotyl length in line fae1 was 0.824 ± 0.03 cm, while CL37 hypocotyls were significantly shorter at 0.147 ± 0.01 cm, 5.6-fold less. Both DG2 and PD1a hypocotyls were significantly longer than those of CL37, averaging 0.504 ± 0.02 and 0.412 ± 0.03 cm, respectively, although neither line produced hypocotyls with lengths equaling those of fae1.

Figure 7.

Reduced hypocotyl elongation and soluble sugar levels in seedlings. A, Length of hypocotyls at 4 DAS. B, Soluble sugar levels at 2 DAS. Colors denote fae1 (red), CL37 (blue), DG2 (green), and PD1a (gray). Values indicate means ± sd; n = 30. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA (P < 0.001) with post-hoc Tukey’s test. Columns with different letters are statistically different.

Plants defective in oil mobilization often exhibit lower soluble sugar content (Eastmond et al., 2015). We analyzed the sugar content of seedlings from lines fae1, CL37, DG2, and PD1a before the onset of carbon fixation in seedlings, when soluble sugar levels increase as a result of the breakdown of oil storage reserves. We cultivated seeds on agar plates for a total of 2 d, then analyzed the soluble sugars with a colorimetric assay (Fig. 7B). The average soluble sugar content of fae1 at 2 DAS averaged 290 ± 12 ng seedling−1, with CL37 being significantly lower at 117 ± 9.3 ng seedling−1. Similar to the analysis of hypocotyl length, both DG2 and PD1a were significantly higher than CL37, averaging 233 ± 13 and 191 ± 8.5 ng seedling−1, respectively. These results align with the hypocotyl results, since DG2 and PD1a both have higher sugar levels but do not equal those of fae1. Together, these results support the conclusion that CL37 has reduced mobilization of storage oil.

DISCUSSION

The potential economic value of plants engineered to produce modified FA is quite large, but only limited success has been achieved in increasing the accumulation of these important products in model plant systems or crops. Seed vigor, while receiving scant notice in the literature, is crucially important to the commercial application of this technology. Unfortunately, the production of modified FA in oilseeds can have the effect of decreasing reproductive success (Cahoon et al., 2006; Li et al., 2012). In the case of HFA-accumulating lines, rates of successful reproduction have varied depending on the plant species and which genes are coexpressed with the hydroxylase (Snapp et al., 2014; Adhikari et al., 2016). The reproductive success of the HFA-accumulating CL37 line (Lu et al., 2006) falls far short of that of its fae1 parent (Fig. 1). Although most CL37 seeds produced a radicle, only 40% of the seeds advanced to the cotyledon stage (Fig. 1B). The coexpression of castor enzymes that are important to TAG synthesis, DG2 (Burgal et al., 2008) or PD1a (van Erp et al., 2011), increased the number of seeds developing to the open cotyledon stage, but neither coexpressed enzyme fully recovered the reproductive success of the fae1 parent (Fig. 1B). We explored the changes in lipid metabolism fostered by coexpression of these genes to better understand why reproduction partially recovered in these lines.

Seedlings of CL37 that grew beyond radicle emergence produced chlorotic cotyledons, but this phenotype was not evident in DG2 and PD1a lines (Fig. 1A). Such chlorosis is an indicator of reduced photosynthetic capacity in lines with altered FA composition (McConn and Browse, 1998; Barkan et al., 2006). Determination of total chlorophyll indicated a 40% reduction in CL37 compared with fae1, while both DG2 and PD1a had chlorophyll contents similar to those of fae1 (Table I). Lower chlorophyll content suggested that it was a failure of photosynthesis that halted the development of CL37 during the transition to photoautotrophic growth. Given the low-chlorophyll and chlorotic phenotype of CL37, we examined the fluorescence characteristics of the leaves using Fv/Fm, which measures the maximum quantum yield of photosynthesis. These measurements were similar for CL37 and fae1 (Table I), indicating that the reaction centers of PSII were operating efficiently (Maxwell and Johnson, 2000). However, the value obtained for ФPSII in CL37 was 64% lower than that in fae1, indicating a disruption in linear electron transport and a significant reduction in overall photosynthetic capacity (Maxwell and Johnson, 2000). Notably, ФPSII values for DG2 and PD1a were equivalent to those of fae1, as for all photosynthetic parameters (Table I). Since the expected differences among these lines are contingent on their lipid metabolism, we proceeded to examine their polar lipids.

In the chloroplast, the predominant lipids are MGDG and DGDG. In our data, these lipids were reduced by 51% and 34%, respectively, in CL37 compared with fae1 at 4 DAS (Fig. 2, A and B). This reduction of galactolipid is likely the major cause of the reduced photosynthetic capacity. Support for this hypothesis comes from DG2 and PD1a, which have higher MGDG and DGDG compared with CL37 and produce healthy cotyledons. While the recovery of MGDG and DGDG synthesis is the most probable cause of the restoration of photosynthesis, it also is worth noting that, at 1 DAS, CL37 contained more than 1.5% HFA in each of these critical plastid lipids and that some HFA persisted in these lipids for at least 4 d (Fig. 2, C and D). Crystallography has shown that these galactolipids interact closely with components of PSII (Jordan et al., 2001; Loll et al., 2005, 2007), so the presence of HFA at 4 DAS may be disruptive and affect downstream electron transport. While the small total HFA in chloroplast lipids in DG2 and PD1a at 4 DAS (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2) makes this seem unlikely, it is nevertheless true that no HFA was detected in lines DG2 and PD1a at 3 DAS, and these lines recovered photosynthetic capacity by 10 DAS (Table I).

A key component of membranes in developing seedlings is PC, which is important not only for its structural role but also as the precursor to the eukaryotic galactolipid synthesis pathway (Miquel and Browse, 1992). We found that CL37 seedlings at 1 DAS were reduced in total PC by 71% while accumulating 10% HFA-PC (Fig. 3). In addition, HFA-PC was detected during the complete 4-d time course (Fig. 3A). This was surprising because PC levels increased dramatically during this period, so the expectation was that, in the absence of new HFA synthesis, the concentration of the modified FA would be diluted. In these lines, the hydroxylase responsible for HFA synthesis is driven by a phaseolin seed-specific promoter not expressed in emerging seedlings (Sengupta-Gopalan et al., 1985). In contrast to CL37, HFA-PC in DG2 and PD1a fell below the detection limit by 4 DAS (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Table S3). Coupled with the reduction in HFA-PC, both these lines had significantly higher PC synthesis during the time course, increasing at 4 DAS by 42% and 46% for DG2 and PD1a, respectively (Fig. 2A). Decreased production of FA in CL37 provides one explanation for the detection of HFA in PC at 4 DAS. In developing CL37, the rate of FA synthesis is, in fact, reduced by 45% compared with the fae1 parent at 4 DAS (Fig. 4). Lines DG2 and PD1a recovered FA synthesis by 55% and 56% compared with CL37, although neither achieved levels similar to those of fae1.

It is possible that HFA or some derived degradation product reduces establishment success for HFA-accumulating lines. Although such toxicity has long been postulated (Cahoon et al., 2006), we are unaware of any concrete data in support of toxic effects in plant cells of either HFA or its derivatives. Our data make this hypothesis less likely, since both DG2 and PD1a accumulate and mobilize significantly more HFA-TAG than CL37 (Supplemental Table S4) yet both are more successful in establishing new plants than CL37 (Fig. 1). These are opposite to the effect expected by the hypothesis that HFA is toxic to the cell. A second hypothesis, that HFA itself is disruptive to membrane function, cannot be completely ruled out. However, as PC is a major membrane component, we note that both DG2 and PD1a lines have more HFA-PC at 0 DAS than CL37, and the proportion of HFA-PC in PD1a is equal to that of CL37 yet its establishment success is far greater (Fig. 3). In the photosynthetic lipids, the amounts of HFA-MGDG and HFA-DGDG are higher in DG2 and PD1a than in CL37 (Fig. 2), and again, they both establish more successfully, further arguing that the mere presence of HFA in the membranes is not disruptive.

Since storage oil is used to provide carbon skeletons for early development, the lower oil content seen for all the lines that accumulate HFA provides one explanation for the reduced FA synthesis (Fig. 4A). Mutants with reduced oil storage often suffer reduced establishment. For example, the tag1 Arabidopsis mutant has 25% less seed oil than its wild-type parent and a 25% reduction in establishment (Lu and Hills, 2002). While this suggests that seed oil is linked directly to seedling establishment, the relationship is more complicated in our experiment, because oil levels do not synchronize with the proportion of fully opened cotyledons. While fae1 has more than 8 μg seed−1 total oil (Fig. 5A), PD1a had 6 μg seed−1 oil, which is equal to that of the tag1 mutant, but only 61% of PD1a seedlings attain fully opened cotyledons. This disparity between seed oil content and successful cotyledon opening also is evident in CL37 and DG2. Line CL37 contained 4 μg seed−1 oil and 40% of the seeds attained opened cotyledons, while seeds of DG2 contained 7 μg seed−1 oil and opened 76% of their cotyledons, which is significantly less than expected for a linear correlation between establishment and oil.

Although lower total oil likely plays a part in the poor seedling development of our lines, evidence suggests that the rate of TAG mobilization can play a more important role in establishment (Kelly et al., 2011). The rate of TAG mobilization in CL37 was 38% of that of fae1 (Fig. 4A). In fact, the rate of TAG mobilization differed for every line, since DG2 and PD1a converted 65% and 49% more than CL37 (Fig. 5A). Germination phenotypes similar to those of CL37 are often noted in plants with poor TAG mobilization. Arabidopsis lines mutated in lipases that catalyze the initial step of TAG breakdown arrested before their cotyledons opened fully (Kim et al., 2014), and in experiments using diphenyl methylphosphonate to prevent the breakdown of oil bodies, TAG was retained in seedlings that became chlorotic and only partially opened cotyledons (Brown et al., 2013). In addition, mutants with defective FA utilization through β-oxidation also show arrested development before cotyledon opening (Fulda et al., 2004; Hayashi et al., 2005; Pinfield-Wells et al., 2005; Park et al., 2013). Interestingly, all the described mutants can be at least partially rescued by exogenous Suc, similar to findings that CL37 seeds more often produce fully open cotyledons when supplemented with Suc (Lunn et al., 2018). Lines DG2 and PD1a may establish more effectively because they are able to mobilize more TAG through β-oxidation during the time course. In comparison with CL37, DG2 and PD1a were able to consume 39% and 34% more TAG, respectively (Fig. 4). Additional support for this interpretation came when we measured decreased hypocotyl elongation and low levels of soluble sugar when CL37 was grown in the dark, as both these processes depend on the mobilization of storage reserves for carbon skeletons. In accord with our interpretation, hypocotyl elongation and sugar accumulation defects of CL37 were relieved substantially in both DG2 and PD1a, indicating that these plants had greater reserves available in the absence of photosynthesis due to higher rates of TAG mobilization (Fig. 4). This higher rate of mobilization for DG2 and PD1a would greatly augment resources for the developing seedling.

The presence of novel FA in seeds may generally slow storage lipid utilization, as shown for lines engineered to contain increased ω-3 polyunsaturated FA that have decreased rates of TAG mobilization (Shrestha et al., 2016). While the failure of HFA utilization might be due to a general weakness of TAG metabolism, our analysis showed that the mobilization of HFA-TAG was affected specifically, and in all cases a clear preference was shown for utilizing 0-HFA-TAG (Fig. 6). This preference must occur in the hydrolysis of TAG, as shown by the retention of HFA-TAG during the earliest stages of oil use (Fig. 6). In many species, TAG lipases have shown a preference for specific FA. In Arabidopsis, the first step of TAG mobilization is its conversion to diacylglycerol plus an FA by the lipases SUGAR-DEPENDENT1 (SDP1) and SDP1-LIKE (Eastmond, 2006). After the conversion to diacylglycerol, sequential reactions by an Arabidopsis diacylglycerol and monoacylglycerol lipase yield FA plus glycerol (Müller and Ischebeck, 2017). Indeed, SDP1 shows substrate preference toward the TAG molecules triolein and trieicosenoin (Eastmond, 2006). In castor, OIL BODY LIPASE1 actively hydrolyzes TAG, favoring the hydrolysis of triricinoleic acid over triolein or trieicosenoin (Eastmond, 2004). The resistance of HFA-TAG to mobilization is best explained by the lack of a lipase in Arabidopsis that efficiently removes the HFA components from TAG, so that HFA-TAG species are retained (Fig. 6).

The reduced rate of HFA-TAG mobilization in CL37 can only further compound its resource starvation under conditions where 51% of all TAG molecules were HFA-TAG. This starvation was not as acute in DG2 and PD1a, although they contained 59% and 55% HFA-TAG, since these lines also contained 50% and 38% more 0-HFA-TAG than CL37 (Supplemental Table S4). The higher establishment of DG2 and PD1a most likely occurred due to their higher rate of 0-HFA-TAG mobilization, which was 42% and 38% greater than in CL37 (Fig. 6D). In addition, DG2 and PD1a were able mobilize significantly greater amounts of HFA-TAG, providing them with even greater resources. The mechanism through which DG2 and PD1a increase the mobilization of HFA-TAG is unclear, but there are suggestive differences between the lines in the stereochemical distribution of HFA moieties. For CL37, the preponderance of HFA is incorporated at the sn-2 position, while both RcDGAT2 and RcPDAT1a incorporate HFA at the sn-3 position of TAG (van Erp et al., 2011). Since the principal TAG lipase of Arabidopsis, SDP1, is related to sn-2 position phospholipase enzymes (Fan et al., 2014), it may prefer hydrolysis of the sn-2 TAG moiety and display reduced activity if that position is occupied by HFA. However, our data show that all lines were able to mobilize HFA-TAG to some extent (Fig. 6); thus, because DG2 and PD1a have greater fractions of HFA-TAG, it becomes more likely that these molecules will be hydrolyzed as 0-HFA-TAG is depleted. This higher level of HFA-TAG mobilization may be an additional contributor to successful establishment.

It is possible that the mobilization of 0-HFA-TAG may produce a positive feedback, whereby greater capacity for TAG hydrolysis fosters increased oil breakdown. In fact, there were differences in HFA-TAG breakdown for all lines, and this hypothesis provides an explanation for the difference in establishment between DG2 and PD1a. Our data show that all lines were able to mobilize HFA-TAG to some extent (Fig. 6). Thus, because DG2 and PD1a had greater fractions of HFA-TAG, it is more likely that these molecules will be hydrolyzed as 0-HFA-TAG is depleted. The accelerated rate of HFA-TAG mobilization may be an additional factor in the establishment differences between all lines and provides an explanation for the divergence between DG2 and PD1a. In fact, DG2 mobilized 22% more HFA-TAG than PD1a (Fig. 6), with a concomitant increase of establishment by 15% (Fig. 1). This significant increase in the mobilization of resources available during establishment provides a plausible explanation for the differences seen between the two lines.

The establishment of DG2 and PD1a is clearly improved over CL37, but it is uncertain if this success will grow with further increases in acyltransferase expression. In that case, pathways of TAG biosynthesis might become more efficient, concentrating HFA in HFA-TAG, as observed when DG2 and PD1a expression doubled the level 2-HFA-TAG (van Erp et al., 2011). However, as HFA proportions increase, the availability of 0-HFA-TAG for mobilization will be reduced, and our conclusions predict that gains in establishment would slow or even be reversed. These results suggest that achieving levels of HFA similar to that of castor oil will likely require the manipulation of TAG, diacylglycerol, and monoacylglycerol hydrolysis with dedicated lipase enzymes.

In this report, we provide a mechanistic explanation for the low establishment rates of plants producing high levels of HFA in their seeds. Our data imply that, in the absence of an HFA-specific TAG lipase, reduced carbon availability leads to reduced FA synthesis, decreasing the expansion of PC and leading to the retention of HFA in both polar and storage lipids. The downstream impact of FA synthesis inhibition reduces the total amount of chloroplast lipids while HFA accumulates in MGDG and DGDG, visually manifested as chlorosis of the cotyledons. This process can be partially circumvented by the coexpression of RcDGAT2 or RcPDAT1A with RcFAH12, sequestering HFA into TAG during seed development, which increases 0-HFA-TAG and the subsequent availability of common FA for β-oxidation. This expansion of resources leads to greater FA synthesis and decreased retention of HFA in the polar lipid during establishment. These findings both diagnose the defects caused by HFA accumulation and provide tools for alleviating a major barrier in the production of tailored oils.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seeds were sterilized with 1 mL of 5% (v/v) bleach and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, followed by a wash with 1 mL of 70% (v/v) ethanol and two washes of water. The seeds were spread on plates of Murashige and Skoog medium without Suc. The seeds were stratified for 2 d at 5°C and then transferred for growth to 22°C with 120 µmol m−2 s−1 continuous white light from broad-spectrum florescent lamps for 1 to 10 d depending on the experiment.

Lipid Extraction

Seedlings were removed from agar plates, extracted in 1 mL of isopropanol containing 0.01% (w/v) butylated hydroxy toluene at 85°C for 15 min, and then thoroughly homogenized. The homogenized tissue was collected with washes of 2 mL of CHCl3 plus 3 mL of methanol, and phase separation of the resulting mixture was induced by adding 1.6 mL of water, 2 mL of CHCl3, and 2 mL of 0.88% (w/v) KCl. The CHCl3 layer was collected, and two back extractions were conducted to increase recovery. The combined chloroform fractions were dried under N2 and resuspended before analysis in 50 μL of toluene. This and all solvents used for lipid analysis contained 0.005% (v/w) butylated hydroxy toluene as antioxidant.

Characterization of TAG Species

Lipid extracts were separated by TLC (Uniplate; Silica gel H; 20 × 20 cm). Lipid species were resolved by development to 12 cm in CHCl3:methanol:acetic acid (93:3:1, v/v/v), dried for 15 min, then further developed for 19 cm in CHCl3:methanol:acetic acid (99:1:1, v/v/v). Lipid bands were visualized under UV after staining with 0.005% (v/w) primulin in 80% acetone. Bands comigrating with 1- and 2-HFA-TAG standard were collected for further analysis.

Characterization of Polar Lipids

A column containing silica gel was equilibrated with 5 mL of CHCl3:methanol (99:1, v/v) and 5 mL of CHCl3:methanol:water (5:5:1, v/v/v). Concentrated lipid extract in CHCl3 was loaded into the column, and neutral lipids were eluted using 5 mL of CHCl3:methanol (99:1, v/v). Polar lipids were eluted using 5 mL of CHCl3:methanol:water (5:5:1, v/v/v). Phase separation was forced on each sample using 2 mL of CHCl3 and 2 mL of 0.88% (v/w) KCl. The CHCl3 phase was collected and dried under N2 and then resuspended in 50 μL of toluene. Polar lipids were separated by TLC using TLC Silica gel 60 F254 plates (EMD Chemicals) impregnated with 0.15 m (NH4)2SO4 and heat activated at 110°C for 3 h. Plates were developed using a solvent system of acetone:toluene:acetic acid (91:30:8, v/v/v). Bands corresponding to PC, MGDG, and DGDG authentic standards were collected for further analysis.

Metabolic Labeling

Seeds were transferred from their stratification medium to agar plates containing 1 μCi mL−1 3H2O for up to 4 d. At each time point, whole seedlings were extracted in 1 mL of isopropanol at 85°C for 15 min. Lipids were extracted from 90 seedlings as before. The chlorophyll fraction was transmethylated and purified by TLC using TLC Silica gel 60 F254 plates (EMD Chemicals) developed with hexane:diethyl ether:acetic acid (70:30:1, v/v/v). Radiolabeling was quantified using a Tri-CARB liquid scintillation analyzer (Packard Instruments).

Photosynthetic Chlorophyll Determination

Seedlings grown for 10 d were homogenized in 80% (v/v) acetone, and the absorbance was measured at both 663 and 645 nm. Chlorophyll (μg g−1) and the chlorophyll a/b ratio were calculated as described (Porra, 2002).

PSII Measurements

Seedlings were grown on agar plates for 10 d under 100 µmol m−2 s−1 continuous white light at 22°C. To determine PSII parameters, plants were measured under light for ФPSII and dark adapted for 2 h for Fv/Fm. These parameters were then analyzed using a FluorCam FC 800-C (Photon Systems Instruments). To determine chlorophyll concentration and chlorophyll a/b ratio, seedlings were homogenized in 80% acetone, and the absorbance was measured at both 663 and 645 nm and calculated using the method described previously (Porra, 2002).

FA Determination

FA composition was determined by transmethylation of whole seedlings using 5% (v/v) sulfuric acid in methanol at 80°C for 90 min. After partition into hexane, samples were analyzed by gas chromatography on a wax column (EC Wax; 30 m × 0.53 m i.d. × 1.20 µm; Alltech) with flame ionization detection. Total oil determination included the addition of a 17:0 TAG standard to the transmethylation reaction.

Determination of Soluble Sugar

A total of three replicates of 300 seedlings were collected at 2 DAS and homogenized with 100% acetone to remove interfering pigments. Samples were centrifuged at 4,000g for 20 min and filtered before the soluble sugars were extracted with two washes of 2.5 mL of 80% ethanol. A further centrifugation was conducted as above, and the supernatant was taken for analysis. To 1 mL of test solution, 5 mL of anthrone reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and incubated at 99°C for 11 min. Sugar concentration was determined by A630 using a Hitachi U-3900 spectrophotometer against water by calculation from a standard curve.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). Data presented in Figures 1 and 7 were analyzed using ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey’s test. All other data were analyzed using Student’s t test.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers Q41131.2 (RcFAH12), XM_002514026 (RcPDAT1A), and ACB30544.1 (RcDGAT2).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Table S1. Total HFA content within DGDG fractions.

Supplemental Table S2. Total HFA content within MGDG fractions.

Supplemental Table S3. Total HFA contained in PC fractions.

Supplemental Table S4. Total and percentage TAG and HFA-TAG species content per seedling 1 DAS.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation Plant Genome Research Program (grant no. IOS-1339385) and the Agricultural Research Center at Washington State University.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Adhikari ND, Bates PD, Browse J (2016) WRINKLED1 rescues feedback inhibition of fatty acid synthesis in hydroxylase-expressing seeds. Plant Physiol 171: 179–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bafor M, Smith MA, Jonsson L, Stobart K, Stymne S (1991) Ricinoleic acid biosynthesis and triacylglycerol assembly in microsomal preparations from developing castor-bean (Ricinus communis) endosperm. Biochem J 280: 507–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan L, Vijayan P, Carlsson AS, Mekhedov S, Browse J (2006) A suppressor of fab1 challenges hypotheses on the role of thylakoid unsaturation in photosynthetic function. Plant Physiol 141: 1012–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Larson TR, Graham IA, Hawes C, Paudyal R, Warriner SL, Baker A (2013) An inhibitor of oil body mobilization in Arabidopsis. New Phytol 200: 641–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgal J, Shockey J, Lu C, Dyer J, Larson T, Graham I, Browse J (2008) Metabolic engineering of hydroxy fatty acid production in plants: RcDGAT2 drives dramatic increases in ricinoleate levels in seed oil. Plant Biotechnol J 6: 819–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon EB, Dietrich CR, Meyer K, Damude HG, Dyer JM, Kinney AJ (2006) Conjugated fatty acids accumulate to high levels in phospholipids of metabolically engineered soybean and Arabidopsis seeds. Phytochemistry 67: 1166–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KD, Dyer JM, Mullen RT (2012) Biogenesis and functions of lipid droplets in plants. Thematic Review Series: Lipid Droplet Synthesis and Metabolism: From Yeast to Man. J Lipid Res 53: 215–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer JM, Stymne S, Green AG, Carlsson AS (2008) High-value oils from plants. Plant J 54: 640–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond PJ. (2004) Cloning and characterization of the acid lipase from castor beans. J Biol Chem 279: 45540–45545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond PJ. (2006) SUGAR-DEPENDENT1 encodes a patatin domain triacylglycerol lipase that initiates storage oil breakdown in germinating Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell 18: 665–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond PJ, Astley HM, Parsley K, Aubry S, Williams BP, Menard GN, Craddock CP, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR, Hibberd JM (2015) Arabidopsis uses two gluconeogenic gateways for organic acids to fuel seedling establishment. Nat Commun 6: 6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Yan C, Roston R, Shanklin J, Xu C (2014) Arabidopsis lipins, PDAT1 acyltransferase, and SDP1 triacylglycerol lipase synergistically direct fatty acids toward β-oxidation, thereby maintaining membrane lipid homeostasis. Plant Cell 26: 4119–4134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda M, Schnurr J, Abbadi A, Heinz E, Browse J (2004) Peroxisomal acyl-CoA synthetase activity is essential for seedling development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 16: 394–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Yagi M, Nito K, Kamada T, Nishimura M (2005) Differential contribution of two peroxisomal protein receptors to the maintenance of peroxisomal functions in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 280: 14829–14835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Ren Z, Lu C (2012) The phosphatidylcholine diacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase is required for efficient hydroxy fatty acid accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 158: 1944–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan P, Fromme P, Witt HT, Klukas O, Saenger W, Krauss N (2001) Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 A resolution. Nature 411: 909–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungas RL. (1968) Fatty acid synthesis in adipose tissue incubated in tritiated water. Biochemistry 7: 3708–3717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AA, Quettier AL, Shaw E, Eastmond PJ (2011) Seed storage oil mobilization is important but not essential for germination or seedling establishment in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 157: 866–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Yang SW, Mao HZ, Veena SP, Yin JL, Chua NH (2014) Gene silencing of Sugar-dependent 1 (JcSDP1), encoding a patatin-domain triacylglycerol lipase, enhances seed oil accumulation in Jatropha curcas. Biotechnol Biofuels 7: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Wallis JG, Skidmore C, Browse J (2006) A mutation in Arabidopsis cytochrome b5 reductase identified by high-throughput screening differentially affects hydroxylation and desaturation. Plant J 48: 920–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst L, Taylor DC, Underhill EW (1992) Fatty acid elongation in developing seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol Biochem 30: 425–434 [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Yu K, Wu Y, Tateno M, Hatanaka T, Hildebrand DF (2012) Vernonia DGATs can complement the disrupted oil and protein metabolism in epoxygenase-expressing soybean seeds. Metab Eng 14: 29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loll B, Kern J, Saenger W, Zouni A, Biesiadka J (2005) Towards complete cofactor arrangement in the 3.0 A resolution structure of photosystem II. Nature 438: 1040–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loll B, Kern J, Saenger W, Zouni A, Biesiadka J (2007) Lipids in photosystem II: interactions with protein and cofactors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1767: 509–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Hills MJ (2002) Arabidopsis mutants deficient in diacylglycerol acyltransferase display increased sensitivity to abscisic acid, sugars, and osmotic stress during germination and seedling development. Plant Physiol 129: 1352–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Fulda M, Wallis JG, Browse J (2006) A high-throughput screen for genes from castor that boost hydroxy fatty acid accumulation in seed oils of transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant J 45: 847–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn D, Wallis JG, Browse J (2018) Overexpression of Seipin1 increases oil in hydroxy-fatty acid accumulating seeds. Plant Cell Physiol 59: 205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell K, Johnson GN (2000) Chlorophyll fluorescence: a practical guide. J Exp Bot 51: 659–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConn M, Browse J (1998) Polyunsaturated membranes are required for photosynthetic competence in a mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant J 15: 521–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel M, Browse J (1992) Arabidopsis mutants deficient in polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis: biochemical and genetic characterization of a plant oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine desaturase. J Biol Chem 267: 1502–1509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller AO, Ischebeck T (2017) Characterization of the enzymatic activity and physiological function of the lipid droplet-associated triacylglycerol lipase AtOBL1. New Phytol 217: 1062–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Gidda SK, James CN, Horn PJ, Khuu N, Seay DC, Keereetaweep J, Chapman KD, Mullen RT, Dyer JM (2013) The α/β hydrolase CGI-58 and peroxisomal transport protein PXA1 coregulate lipid homeostasis and signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 1726–1739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinfield-Wells H, Rylott EL, Gilday AD, Graham S, Job K, Larson TR, Graham IA (2005) Sucrose rescues seedling establishment but not germination of Arabidopsis mutants disrupted in peroxisomal fatty acid catabolism. Plant J 43: 861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra RJ. (2002) The chequered history of the development and use of simultaneous equations for the accurate determination of chlorophylls a and b. Photosynth Res 73: 149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta-Gopalan C, Reichert NA, Barker RF, Hall TC, Kemp JD (1985) Developmentally regulated expression of the bean β-phaseolin gene in tobacco seed. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 3320–3324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severino LS, Auld DL, Baldanzi M, Cândido MJ, Chen G, Crosby W, Tan D, He X, Lakshmamma P, Lavanya C (2012) A review on the challenges for increased production of castor. Agron J 104: 853–880 [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha P, Callahan DL, Singh SP, Petrie JR, Zhou XR (2016) Reduced triacylglycerol mobilization during seed germination and early seedling growth in Arabidopsis containing nutritionally important polyunsaturated fatty acids. Front Plant Sci 7: 1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snapp AR, Kang J, Qi X, Lu C (2014) A fatty acid condensing enzyme from Physaria fendleri increases hydroxy fatty acid accumulation in transgenic oilseeds of Camelina sativa. Planta 240: 599–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Erp H, Bates PD, Burgal J, Shockey J, Browse J (2011) Castor phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase facilitates efficient metabolism of hydroxy fatty acids in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 155: 683–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Erp H, Shockey J, Zhang M, Adhikari ND, Browse J (2015) Reducing isozyme competition increases target fatty acid accumulation in seed triacylglycerols of transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 168: 36–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]