Abstract

Background: The need to prevent postoperative adhesions after surgery has been considered a significant challenge in thoracic surgery, especially with the advent of video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS). While preventive materials for postoperative adhesions have been studied for many years, they are all still in the development phases.

Methods: In this animal study, an insoluble hyaluronic acid membrane was used in VATS for wedge resection to test its operability and to examine the body's response to the membrane. Ten beagles were divided into two groups, an experimental group and a negative control group. In the experimental group, an insoluble hyaluronic acid membrane containing glycerol was used as the test membrane (10 x 10 x 0.1 cm3). The test membrane was implanted in the left thoracic cavity of the animal under VATS following wedge resection. The animals were observed for two weeks and then euthanized for examination.

Results: Macroscopically, the median adhesion score was lower in the experimental group (0) than in the control group (2.5). On histopathological examination, the test membrane elicited only a minor inflammatory response and foreign body reaction.

Conclusion: The test membrane showed satisfactory operability and appears to be a practical material to prevent postoperative adhesions after thoracic surgery in VATS.

Keywords: Preventing adhesion, VATS, thoracic surgery, insoluble hyaluronic acid membrane

Introduction

Postoperative adhesions occur at a high rate after surgery, and their adverse effects are widely recognized as peritoneal adhesions after abdominal surgery, which are known to cause organ disorders such as abdominal pain, ileus, and infertility 1, 2. Moreover, such postoperative adhesions after abdominal surgery are known to occur after endoscopic surgery, as well as after laparotomy 3. While postoperative adhesions also occur at a high rate after thoracic surgery, their association with organ disorders has rarely been reported 4. Nonetheless, postoperative adhesions after thoracic surgery can cause major adverse effects in cases requiring repeated thoracic surgery 5-9.

In addition, problems with postoperative adhesions are also described in video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) 10-12. Since the surgical manoeuvers available in VATS are restricted, the presence of adhesions is predicted to be a greater problem, because the surgical field of view is limited compared with thoracotomy. From the standpoint of VATS development in the future, the prevention of postoperative adhesions is the challenge. In prevention of adhesions after abdominal surgery, a film consisting primarily of a cellulose derivative (carboxymethyl-cellulose) was developed and subsequently commercialized. This has been shown to be effective in reducing postoperative adhesions after abdominal surgery 13, 14 and also in prevention of adhesions after thoracic surgeries in pediatric cardiac surgery 15, as well as in rat mediastinoscopy 10. There are several methods by which carboxymethyl-cellulose membranes are used in laparoscopy 16-18, and this method has shown effectiveness in laparoscopy 19, 20. On the other hand, an anti-adhesion film for use in thoracic surgery is not commercially available 21-24.

An insoluble hyaluronic acid membrane containing glycerol has been developed that shows greater effects in preventing postoperative adhesions after thoracic surgery than the above-mentioned carboxymethyl-cellulose membrane 25. In a previous study in which thoracotomy was performed in dogs with the use of a novel membrane that uses surface water induction technology to prevent adhesions (insoluble hyaluronic acid membrane), we also showed that this membrane is effective in preventing postoperative adhesions after thoracotomy 26.

Based on the above, it is predicted that materials that are highly effective in preventing postoperative adhesions after thoracic surgery and can be used in VATS with a small incision of about 3-6 cm 27 will become essential in cardiac and respiratory surgeries. In a previous study, when a large incision was made in situations such as thoracotomy, we were able to cover the whole target site by inserting the membrane into the thoracic cavity after gently folding it in half. However, because the membrane was not strong enough to withstand damage caused by solid instruments such as tweezers and forceps, their use in VATS surgery should be evaluated.

This study examined the operability, safety, and efficacy of an anti-adhesive insoluble hyaluronic acid membrane in VATS.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (Permit number 27-36). All treatments involving experimental animals were conducted in accordance with the Animal Experiments Subcommittee of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals Eighth Edition (Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals; National Research Council).

Test membrane implantation

Ten male TOYO beagles (9.8-10.5 kg) were purchased from Kitayama Labs Co. Ltd. (Nagano, Japan). The experiment consisted of two groups: the experimental group and the control group (n=5 each). Animals were given cefovecin sodium (8 mg/kg, sc; Convenia®, Zoetis Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) to prevent infection and buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg, sc; Buprenorphine for injection 0.2 mg, Nissin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for analgesia. Subsequently, animals were pre-treated with atropine sulphate, butorphanol tartrate (0.2 mg/kg, iv; Vetorphale®, Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and midazolam (0.2 mg/kg, iv; Midazolam injection [SANDOZ], Sandoz K.K., Tokyo, Japan), followed by general anesthesia induction with propofol (6 mg/kg, iv; “Mylan,” Mylan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Following tracheal intubation, anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane inhalation (1-2%, Isoflurane for animals, Intervet K.K., Tokyo, Japan). Respiratory management was performed with manual bag-mask ventilation and intermittent positive pressure breathing through an artificial anesthesia device.

An insoluble hyaluronic acid membrane containing glycerol was used as the test membrane (10 cm x 10 cm x 0.1 cm). The test membrane was implanted in the left thoracic cavity of the animal under VATS. A 12-mm-diameter port was created at the tenth intercostal space on the left side with a trocar, and a 35-mm-diameter small incision for operation was subsequently created at the fifth intercostal space on the left side under video camera monitoring. A wound protector (for 35-mm-diameter incisions) (Wrap Protector FF0707, Hakko Co., Ltd., Nagano, Japan) was inserted at the small incision for operation. Intercostal nerve block was performed in advance with bupivacaine (Marcaine injection 0.5%, AstraZeneca plc, Osaka, Japan) for port and small incision sites. An automatic suture device (Endo GIA, 45 mm, Covidien Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was inserted from the port at the tenth intercostal space. Grasping forceps were then inserted from the small incision to hold the lung parenchyma, and the automatic suture device was used for stapling and dissection. Then, dissected lung tissue was removed from the small incision. In the experimental group, after the adhesion-preventing membrane was inserted from the small incision and placed between the visceral pleura and parietal pleura, and placed the center of the test membrane just under the small incision. A drain tube (Phycon tube SH No. 3: 2.5 mm inner diameter, 4.0 mm outer diameter, Fuji Systems Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted. After gradually re-expanding the lung lobes, the trocar was removed. The wound was closed using 2/0 synthetic absorbable suture (Biosyn, Covidien Japan Inc.) using a conventional method. For the control group, a similar procedure was used without inserting the adhesion-preventing membrane, and the wound was subsequently closed.

Any abnormalities such as pneumothorax and pleural effusion were checked on the day after surgery. Pleural effusions were removed, if present, once a day, and their volumes were recorded. Chest drains were removed when pleural effusions were no longer observed.

At postoperative week 2, animals were anaesthetized similarly to the operation for membrane insertion and then euthanized with an overdose of potassium chloride solution under deep general anesthesia. Subsequently, blood was removed, and the chest was re-opened with median sternotomy.

Observation and test methods

The day of implantation was specified as day 1 of observation. At the time of sacrifice when the chest was re-opened, adhesions, if present, were dissected macroscopically using Kelly forceps, Metzenbaum scissors, and cotton swabs, and the strength of adhesions was evaluated and scored based on the degree of bluntness or sharpness of the dissection process (0=no need to dissect; 1=film-like adhesion, can be dissected easily; 2=mild adhesion, can be dissected; 3=moderate adhesion, difficult to dissect; 4=strong adhesion, impossible to dissect), using the same scoring systems as in a previous report 26. The macroscopic findings of adhesions after thoracotomy were compared statistically by comparing the adhesion scores of the Experimental group and the Control group using the Mann-Whitney U test.

For histological examination, parietal pleura and lung samples were collected near the test membrane insertion site. Samples were taken from two parts. The one was from the parietal pleura adjacent to the suture site of the small incision of the fifth intercostal space. The other one was from the visceral pleura adjacent to lung resection site in the cranial lobe of the left lung. Removed pleural and lung tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution for one week at room temperature. After fixation, intercostal tissues were cut perpendicularly from the parietal to the visceral direction to create tissue slice samples that were embedded in paraffin blocks. After sectioning, samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Under an optical microscope, histopathological lesions were categorized according to the criteria for histopathological classification described below, and images of a representative view for each finding were taken. To compare the effects of the test membrane in preventing adhesions, the adhesion site and dorsal aspect of the lungs (including visceral pleura) were histopathologically evaluated in terms of tissue adhesion, fibrosis, mesothelial cell hypertrophy, cuboidal epithelialization of type II alveolar epithelial cells, and mononuclear cell infiltration in animals with adhesions between the lung and chest wall and in animals with interlobular adhesions. In animals without adhesions, the dorsal aspect of the lungs (including visceral pleura) was similarly evaluated.

The criteria for histopathological classification were the following: (adhesion: -, absent; +, present), (fibrosis in pleura: +, localized; ++, diffuse), (mesothelial cell hypertrophy in pleura: -, absent; +, mild), (alveolar epithelial cell cuboidal epithelialization in alveoli: -, absent; +, localized; ++, diffuse), (mononuclear cell infiltration in alveoli: -, absent; +, localized), and (mononuclear cell infiltration in interstitium: -, absent; +, localized; ++, diffuse).

Results

Insertion of an adhesion prevention membrane

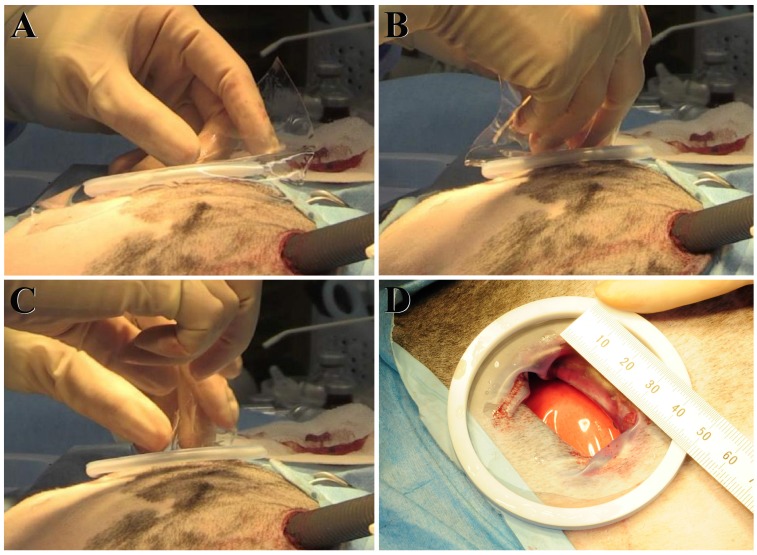

After immersion in saline, the membrane became rapidly and sufficiently pliable, and it was not cracked by normal handling. In one animal (E4), the membrane was torn into multiple pieces while delivering it from the small ~3.5-cm incision for left-sided VATS in the thoracic cavity, making it difficult to completely cover the target site. Membrane insertion in all other animals in the experimental group was achieved successfully (Fig 1). Moreover, there were no differences in operability with wet gloves or with a wet wound protector placed at the small incision site. The membrane did not hinder the chest closing procedure.

Fig 1.

Membrane insertion procedure. In the experimental group, the adhesion-preventing membrane is inserted from the small incision and placed between the visceral pleura and parietal pleura. Membrane insertion in all animals except for E4 in the experimental group was achieved successfully in the order of panel A to panel D.

Macroscopic findings after thoracotomy

In the experimental group, adhesions were observed between the chest wall and lungs in 2/5 animals, and blunt dissection of the adhesions was difficult to achieve in one animal (E4) (adhesion scores: 3 for E4, 0 for E5, 2 for E6, 0 for E7, and 0 for C10). Pulmonary interlobular adhesions were observed in 2/5 animals, but blunt dissection could be achieved in all adhesions (adhesion scores: 0 for E4, 0 for E5, 0 for E6, 2 for E7, and 2 for E10). The median adhesion score was 0. In the control group, adhesions were observed between the chest wall and lungs in 3/5 animals, and blunt dissection of the adhesions was difficult to achieve in one animal (C2) (adhesion scores: 0 for C1, 3 for C2, 0 for C3, 1 for C8, and 1 for C9). Interlobular adhesions were observed in all 5/5 animals, and blunt dissection was difficult to achieve in 4 animals (adhesion scores: 3 for C1, 3 for C2, 2 for C3, 4 for C8, and 3 for C9). The median adhesion score was 2.5. (Table 1) The adhesion score of the Experimental group was significantly lower (P<0.01, Mann-Whitney U test). In both the implant group and the control group, adhesions were completely absent at the VATS insertion port (tenth dorsal intercostal space).

Table 1.

Macroscopic findings of adhesions after thoracotomy

| Control group | Experimental group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of animals examined | 5 | 5 | |

| Adhesion score | |||

| Between the chest wall and lungs (1/2/3/4) | 3 (2/0/1/0) | 2 (0/1/1/0) | |

| Pulmonary interlobular adhesions (1/2/3/4) | 5 (0/1/3/1) | 2 (0/2/0/0) | |

| Median adhesion score | 2.5 | 0.0 | |

Adhesion scores: the degree of bluntness or sharpness of the dissection process (0, no need to dissect; 1, film-like adhesion, can be dissected easily; 2, mild adhesion, can be dissected; 3, moderate adhesion, difficult to dissect; 4: strong adhesion, impossible to dissect).

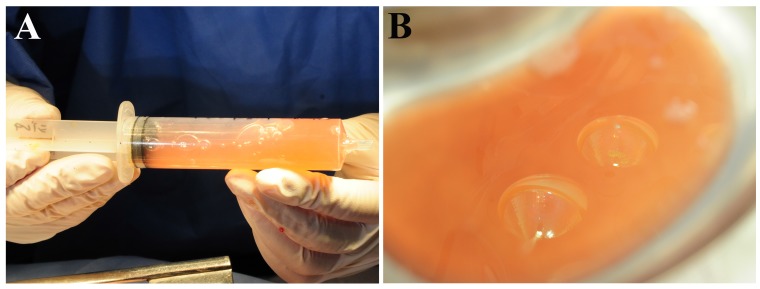

With regard to the pleural effusions, 4/5 animals in the experimental group (excluding E4) showed pale yellow, viscous pleural effusions (90-110 mL/dog) (Fig 2). Most of the test membranes showed a mucoid-like appearance, with some showing a mass of a few mm mixed in the pleural effusion.

Fig 2.

Pleural effusions observed at the re-thoracotomy. Four of five animals in the experimental group (excluding E4) show pale yellow, viscous pleural effusions (90-110 mL/dog).

Histopathological evaluation

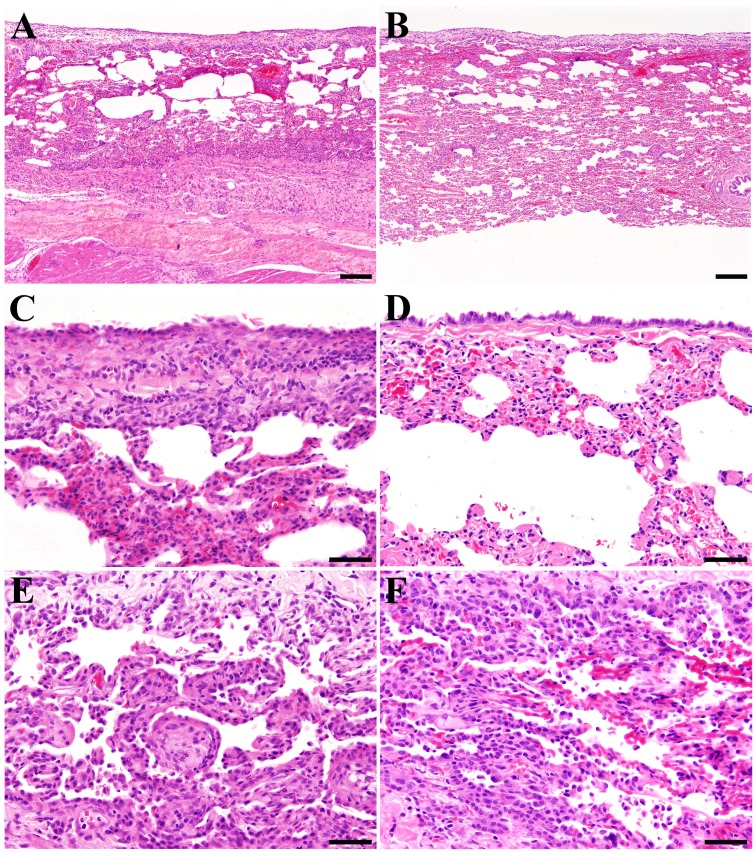

There were no obvious difference between the experimental group and the control group in the incidence or severity of adhesion of the lung and chest wall, pulmonary interlobular adhesion, pleural fibrosis (Fig 3A and B), pleural mesothelial cell hypertrophy (Fig 3C and D), alveolar epithelial cell cuboidal epithelialization (Fig 3E and F), alveolar mononuclear cell infiltration (Fig 3E and F), and interstitial mononuclear cell infiltration (Table 2).

Fig 3.

Histopathological changes in the chest wall and lungs at the re-thoracotomy. The test membrane elicits only a minor inflammatory response and foreign body reaction compared with the control group. (A, B) Pleural fibrosis (++) in a control animal (A) and an experimental group animal (B). (C, D) Mesothelial cell hypertrophy (+) in a control animal (C) and an experimental group animal (D). (E, F) Alveolar epithelial cell cuboidal epithelialization (+) and mononuclear cell infiltration (+) in a control animal (E) and an experimental group animal (F). (A-F: Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Bar: A, B = 200 μm, x 10, C-F = 50 μm, x 40.

Table 2.

Incidence of histopathological changes in the left lung and left chest wall

| Control group | Experimental group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of animals examined | 5 | 5 | |

| Adhesions | |||

| Lung and chest wall (+) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| Pulmonary interlobular (+) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | |

| Pleura | |||

| Fibrosis (+/++) | 5 (2/3) | 5 (0/5) | |

| Mesothelial cell hypertrophy (+) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) | |

| Alveoli | |||

| Epithelial cell cuboidal epithelialization (+/++) | 3 (3/0) | 5 (4/1) | |

| Mononuclear cell infiltration (+) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| Interstitium | |||

| Mononuclear cell infiltration (+/++) | 4 (4/0) | 3 (2/1) | |

Criteria for histopathological classification: Adhesions: +, present; Fibrosis in the pleura: +, localised; ++, diffuse; Mesothelial cell hypertrophy in the pleura: +, mild; Alveolar epithelial cell cuboidal epithelialization: +, localised; ++, diffuse; Alveolar mononuclear cell infiltration: +, localised; Interstitial mononuclear cell infiltration: +, localised; ++, diffuse.

Discussion

One of the major differences between thoracotomy and VATS is the size of the incisions associated with the surgery 27. The insoluble hyaluronic acid membrane can be cracked and torn into multiple pieces if it is completely folded. In fact, in one animal of the experimental group (E4), the membrane tore into several pieces during its delivery from the small incision to the thoracic cavity, and complete coverage of the target site could not be achieved. However, it was possible to insert the test membrane by grasping the four corners of the test membrane. With this procedure, the membrane forms a drawstring pouch and can be dropped into the thoracic cavity by pushing the center of the membrane into the thoracic cavity, without folding it from the small incision. Although it is necessary to have some experience to insert the membrane from a small incision, the technique does not require skillful technique. Moreover, this procedure can be achieved with both wet and dry surgical instruments and gloves. The membrane showed adhesion-preventing effects simply by placing the membrane without attachment to wrap the target site. From this point of view, this membrane was superior to the carboxymethyl-cellulose membrane for laparoscopy use. The size of the small incision created in the present study (~3.5 cm) was similar to the typical size of incision that is created to remove pulmonary lobes in clinical lobectomy 27, indicating that this membrane can be used in a practical manner in VATS in the clinical setting.

In the experimental group, only one animal (E4) developed an adhesion (left chest wall and lung) with an adhesion score of 3 (blunt dissection of the adhesion difficult to achieve), which can be clinically problematic with VATS. In this animal, the test membrane cracked during insertion and was torn into multiple pieces. The reason for the development of the clinically problematic adhesion was insufficient coverage of the target site. This animal did not show a pleural effusion at sacrifice. This was because the test membrane was manufactured by applying surface water induction technology, which enables integration of water by glycerol and then absorption of a large amount of water by insoluble hyaluronic acid to create a barrier 25. Consequently, this physical property of this test membrane enables prevention of adhesions between the chest wall and lung. As possible causes of the development of adhesions, the test membrane may lose its physical properties as a barrier. By cracking the membrane during insertion, this membrane loses its surface water induction property, and the uncovered portion may develop adhesions.

In the macroscopic examination at sacrifice, no exudative changes suggestive of inflammatory responses were observed in the thoracic cavity in the experimental group. Histopathological analysis also showed no apparent induction of inflammatory changes or a foreign body reaction. This result suggests that the test membrane dissolves spontaneously within the thoracic cavity to be absorbed into the body and does not remain as a foreign substance, thus not causing an inflammatory response or foreign body reaction. Although the chest drain was removed a few days postoperatively when a pleural effusion was no longer observed, a pale yellow pleural effusion (90-110 mL/dog) was observed in 4/5 animals in the experimental group at sacrifice. This pale yellow pleural effusion might be generated during the process to dissolve and absorb the test membrane. In human medicine, the clinical symptoms of pleural effusions are considered to be dependent on the underlying lung disease 23, 28, 29, and the pleural effusion observed in the present study would be unlikely to become a problem in the clinical setting.

The extent of surgical invasiveness is one of the important issues that must be addressed. While postoperative adhesions after thoracic surgery occurs at a high rate 5-7, 9, the incidence of adhesions depends on the intraoperative invasiveness of the surgical procedure. In the present study, only wedge resection of the lung lobe was performed using an automatic suture device. In this procedure, intraoperative tissue dissection was not necessary, and only a small amount of bleeding can be expected. This is the reason for the fewer adhesions that occurred even in the control group, and VATS is less invasive than thoracotomy. Actually, problems with postoperative adhesions have been described in VATS 10-12. Therefore, in future investigations, induction of adhesions will need to be compared between use and non-use of the test membrane in surgeries with a greater degree of invasiveness, such as lobectomy or pericardial incision, instead of wedge resection.

In conclusion, the test membrane used in this study showed satisfactory operability not only in typical thoracotomy, but also in VATS, which is becoming increasingly common. Its easy delivery and spread within the thoracic cavity may be well suited for VATS procedures. This test membrane elicited only a minor inflammatory response and foreign body reaction and appears to be practical as a material to prevent postoperative adhesions after thoracic surgery and VATS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dainichiseika Color & Chemicals Mfg. Co., Ltd. for providing the test membrane samples used in this study.

Author Contributions

AU summarized the experimental findings, wrote the main manuscript text, and prepared Tables 1 and 2 and Figures 1 and 2. TF and TT were the anesthetists or assistants during the implantation of the experimental test membrane. YH and MS prepared Figure 3 and performed histopathological diagnoses. RT was the primary investigator and was responsible for the study design and funding. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

RT received funding from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (National Research and Development Agency) as the Head of the Department of Veterinary Surgery of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology and these funds were used to purchase the dogs and medicine used in this study. AU, TF and TT used these dogs and medicine for this study. YH and MS declare no potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hong G, Vilz TO, Kalff JC, Wehner S. [Peritoneal adhesion formation] Chirurg. 2015;86:175–80. doi: 10.1007/s00104-014-2975-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ten Broek RP, Issa Y, van Santbrink EJ, Bouvy ND, Kruitwagen RF, Jeekel J. et al. Burden of adhesions in abdominal and pelvic surgery: systematic review and met-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5588. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muschalla F, Schwarz J, Bittner R. Effectivity of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (TAPP) in daily clinical practice: early and long-term result. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4985–94. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satoh H, Kurishima K, Kagohashi K. Pneumothorax with postoperative complicated pleural adhesion. Tuberk Toraks. 2013;61:357–9. doi: 10.5578/tt.6268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oizumi H, Naruke T, Watanabe H, Sano T, Kondo H, Goya T. et al. [Completion pneumonectomy-a review of 29 cases] Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;38:72–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yim AP, Liu HP, Hazelrigg SR, Izzat MB, Fung AL, Boley TM. et al. Thoracoscopic operations on reoperated chests. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:328–30. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Getman V, Devyatko E, Wolner E, Aharinejad S, Mueller MR. Fleece bound sealing prevents pleural adhesions. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2006;5:243–6. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2005.121129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loop FD. Catastrophic hemorrhage during sternal reentry. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984;37:271–2. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)60727-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braxton JH, Higgins RS, Schwann TA, Sanchez JA, Dewar ML, Kopf GS. et al. Reoperative mitral valve surgery via right thoracotomy: decreased blood loss and improved hemodynamics. J Heart Valve Dis. 1996;5:169–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buyukkale S, Citak N, Isgorucu O, Sayar A. A bioabsorbable membrane (Seprafilm(R)) may prevent postoperative mediastinal adhesions following mediastinoscopy: an experimental study in rats. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:11544–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruggmann D, Tchartchian G, Wallwiener M, Munstedt K, Tinneberg HR, Hackethal A. Intra-abdominal adhesions: definition, origin, significance in surgical practice, and treatment options. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:769–75. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Goor H. Consequences and complications of peritoneal adhesions. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(Suppl 2):25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamond MP, Burns EL, Accomando B, Mian S, Holmdahl L. Seprafilm((R)) adhesion barrier: (2) a review of the clinical literature on intraabdominal use. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9:247–57. doi: 10.1007/s10397-012-0742-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozerhan IH, Urkan M, Meral UM, Unlu A, Ersoz N, Demirag F. et al. Comparison of the effects of Mitomycin-C and sodium hyaluronate/carboxymethylcellulose [NH/CMC] (Seprafilm) on abdominal adhesions. Springerplus. 2016;5:846. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2359-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefort B, El Arid JM, Bouquiaux AL, Soule N, Chantreuil J, Tavernier E. et al. Is Seprafilm valuable in infant cardiac redo procedures? J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;10:47. doi: 10.1186/s13019-015-0257-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sumi Y, Yamashita K, Kanemitsu K, Yamamoto M, Kanaji S, Imanishi T. et al. Simple and Easy Technique for the Placement of Seprafilm During Laparoscopic Surgery. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:1462–5. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuruta A, Itoh T, Hirai T, Nakamura M. Multi-layered intra-abdominal adhesion prophylaxis following laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1400–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koketsu S, Sameshima S, Okuyama T, Yamagata Y, Takeshita E, Tagaya N. et al. An effective new method for the placement of an anti-adhesion barrier film using an introducer in laparoscopic surgery. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:551–3. doi: 10.1007/s10151-015-1340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altuntas YE, Kement M, Oncel M, Sahip Y, Kaptanoglu L. The effectiveness of hyaluronan-carboxymethylcellulose membrane in different severity of adhesions observed at the time of relaparotomies: an experimental study on mice. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1562–5. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusuki I, Suganuma I, Ito F, Akiyama M, Sasaki A, Yamanaka K. et al. Usefulness of moistening seprafilm before use in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:e13–5. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828f6ec1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takagi K, Tsuchiya T, Araki M, Yamasaki N, Nagayasu T, Hyon SH. et al. Novel biodegradable powder for preventing postoperative pleural adhesion. J Surg Res. 2013;179:e13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izumi Y, Takahashi Y, Kohno M, Nomori H. Cross-linked poly(gamma-glutamic acid) attenuates pleural and chest wall adhesions in a mouse thoracotomy model. Eur Surg Res. 2012;48:93–8. doi: 10.1159/000337033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karkhanis VS, Joshi JM. Pleural effusion: diagnosis, treatment, and management. Open Access Emerg Med. 2012;4:31–52. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S29942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akerberg D, Posaric-Bauden M, Isaksson K, Andersson R, Tingstedt B. Prevention of pleural adhesions by bioactive polypeptides - a pilot study. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:1720–6. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noishiki Y, Shintani N. Anti-adhesive membrane for pleural cavity. Artif Organs. 2010;34:224–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2009.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uemura A, Nakata M, Goya S, Fukayama T, Tanaka R. Effective new membrane for preventing postthoracotomy pleural adhesion by surface water induction technology. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrott PW Jr, Jones DR. Teaching video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) lobectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(Suppl 3):S207–11. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.07.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu H. Management of pleural effusion, empyema, and lung abscess. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011;28:75–86. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1273942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Na MJ. Diagnostic tools of pleural effusion. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2014;76:199–210. doi: 10.4046/trd.2014.76.5.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]