Background

As health care moves toward value‐based care and population health, incorporating social determinants (SDs: social, economic, legal, environmental factors) in curricula is important to understand traditionally marginalized populations, social context, and potential for civic advocacy by physicians.1, 2 SDs account for 50% of the overall impact on health, whereas clinical care accounts for 20%.3 Learners may have different backgrounds from their patients and may not understand challenges presented by SDs and the need for patient‐centered care.4 Only 15% of U.S. medical students were of low socioeconomic status (2003–2006)5 and 19% had family income < $62,725/year (2012).6 Not surprisingly, learners may not view social factors as clinically relevant7 and have an increasingly negative attitude toward the underserved as they progress in their training,8 despite the ACGME calling for teaching residents to “obtain and use information about their own population of patients and the larger population from which their patients are drawn.”9

Social determinants are not part of the EM core curriculum.10, 11 However, EDs bear a disproportionate burden in caring for patients who are un‐ or underinsured. Some residencies have identified teaching SDs as important to improving patient care and have taught in classroom or in situ using methods such as an orientation month including activities such as home visits, community tours, and community visits,7 rotating at community organizations.12, 13 SDs have not been part of our curriculum until now. We incorporated the Missouri Community Action Network's Poverty Simulation during Intern Orientation (2017) to give the interns an understanding of the challenges our patients face with SDs so that they would factor in SDs as part of their treatment plan.

Explanation

During our institution's intern orientation week, the department of emergency medicine led a poverty simulation that placed new interns from the departments of emergency medicine, internal medicine, family medicine, and obstetrics & gynecology in the shoes of low‐income patients. Learners were grouped into families of 1 to 5, assigned the role of a family member, and tasked with getting through a simulated month, broken down into four 15‐minute weeks during the 1‐day simulation session, during which they had to accomplish instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs: e.g., going to work, applying for public benefits, paying bills).

Twelve stations were manned by faculty, senior residents, and individuals from community‐based organizations who re‐created realistic situations, which fostered relationship building between physicians and community partners (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ground Rule and Role Descriptions

| Ground Rules | Description |

|---|---|

| Family | Starts with a certain amount of cash on hand and resources (appliances, durable good, maybe a car title). If housed must make mortgage, utility, food/clothing payments. Children > 5 years must go to school. Children < 5 years must be dropped off at childcare. Adults with jobs should go to the employer. Other than this, families have discretion of which stations to go to in order to accomplish all of the tasks on hand. |

| Transportation | Going to each station requires a transportation pass, which is collected at that station and represents transportation costs (if has car—cost of gas/maintenance; if no car—cost of public transit). |

| Timing of week. | Keeps time (15‐minute weekday, 5‐minute weekend for total of 20 minutes each week). Total simulation is 4 weeks or 1 month. |

| Role | Description |

| Family | Made up of one to five individuals. May be a combination of adults and children. Plans to accomplish IADLs each week and goes to stations of choosing each week to accomplish IADLs. |

| Employer | Ensures that employees are not more than 3 minutes late. Pays employees each week. Fires employees. Takes job applications. Interviews new job applicants. |

| Interfaith services | Runs homeless shelter. Provides resources for families seeking assistance. |

| Banker | Cashes checks. Redeems “luck‐of‐the‐draw” cards. |

| Utilities company | Takes utilities payments. Issues utility shut off warnings for those who are late in payments. Issues utility shut off notices starting week 3 of simulation. |

| School | Provides supervision for children during school time. Collects fees for children's school‐related expenses. Issues tardy notices to parents whose children are late. |

| Community action agency | Provides assistance to families requesting assistance. Issues vouchers that are redeemable at Supercenter for food. Helps families with forms. |

| Mortgage company | Takes mortgage payments. Issues eviction notices for those who are late in payments starting in week 3 of simulation. Goes out and reminds families about late payments starting week 3 of simulation. |

| Social services | Schedules individuals for appointments to apply for public benefits (food stamps, cash aid). Issues public benefits applications. Reviews public benefits applications. Issues food stamps cards and cash aid checks. |

| QuikStop | Sells transportation passes. Makes payday loans. Issues loans against car titles. |

| Supercenter | Sells food and clothing. Issues starvation notices to families who are behind on food and clothing payments. Employs individuals part time. |

| Childcare | Provides childcare for minor children too young for school. Collects childcare payments. |

| Pawnshop | Negotiates with individuals who are looking to pawn appliances and durable goods. Issues cash for items pawned by families. |

| Police | Arrests individuals who are stealing or fighting. Places these individuals in jail. Investigates claims of robbery. |

| Thief | Steals from families as opportunities arise. Avoids police. |

| Facilitator | Keeps time. Hands out “luck‐of‐the‐draw cards.” Answers questions. Leads large group debrief. |

IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

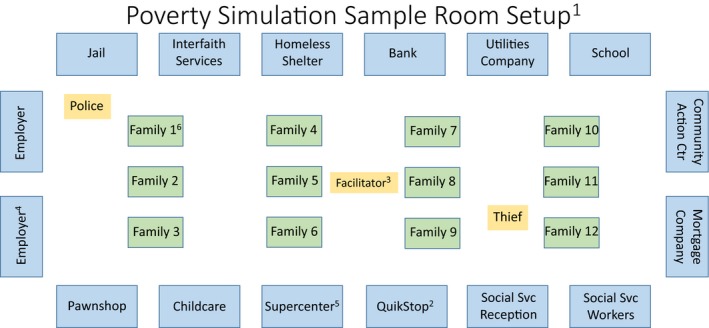

Learners visited different stations, where different IADLs occurred and reflected the stress that families may face (Figure 1). Learners strategized which stations to visit to accomplish their IADLs. For example, those with full‐time employment spent 7 of their 15‐minute week at work. Participants waited in line for services like payday loans, which impeded their ability to adhere to a schedule (e.g., picking children up from school). During the weekend (5 minutes), families regrouped, reviewed the past week, and strategized for the upcoming week. At the end of the 1‐day simulation, the facilitator led a debriefing, giving participants an opportunity to reflect upon their experiences.

Figure 1.

Poverty simulation sample room setup.11 Each week is 15 minutes, with a 5‐minute weekend. Total simulation month is 4 weeks.2 To move between stations, learners must use a transportation pass, which represents costs of travel by public transit or public vehicle (purchased at QuikStop).2 Facilitator keeps time and hands out “Luck of the Draw” cards, which represent positive and negative life events, such as finding money on the street or having one's car broken into. Learners must follow the directions on the card.2 Full‐time employees must be at employer for 7 minutes/week. Part‐time employees must be at employer for 4 minutes/week. Employees cannot be more than 3 minutes late.3 Supercenter sells medications, food, and clothing. Also provides part‐time employment.4 Participants included learners from the departments of emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, and obstetrics & gynecology at Harbor UCLA Medical Center and guest learners from the University of California at Los Angeles‐Olive View emergency medicine and internal medicine residency programs.

Description

Our simulation provided learners with insight into the daily challenges their low‐income patients face. During the simulation, many appeared frustrated with service providers and other family members; others almost came to tears. After the hour‐long simulation, we held a large group debrief where learners expressed stress of juggling various ADLs under extreme time constraints and sensed a lack of control. When costs exceeded income, learners had to choose between housing, utilities, food, medications, and clothing. One learner withheld medications so their family could eat.

Learners highlighted the challenges of applying for public benefits, as multiple visits to social services resulted only in waiting months for approval. They experienced difficulty obtaining employment, even if they wanted to work. Those who found employment suffered from inflexibility that impeded their IADLs.

We linked the learners’ insights back to the challenges that our patients face. We discussed topics such as why patients come late at night or on weekends to the ED for medication refills or other seemingly nonurgent problems, why patients may not fill their antibiotics, and how learners could engage in advocacy to address some of these challenges.

The simulation engendered camaraderie among the interns, who are from diverse backgrounds but, together, will care for our underserved patient population. Learners also understood the importance of considering and discussing SDs when caring for our patients and creating treatment plans. Although learners were subjected to extreme stress for only a few hours, it was evident that they suspended reality and truly experienced the emotions and struggles their patients routinely face.

The poverty simulation introduced new interns to challenges that low‐income patients face and why SDs are significant. Combined with ongoing training and collaboration with community partners, physicians may better understand their patients and practice patient‐centered care.

AEM Education and Training 2018;2:51–54.

New Ideas in B‐E‐D‐side Teaching

These are educational case reports. These may be single‐center reports that do not contain robust evaluation data. Authors are invited to describe innovations and techniques in bedside teaching that may include a focus on instructional methods, team and/or patient involvement, procedural teaching, and the art of clinical medicine. Submissions should follow the structure B‐E‐D as described below. Tips that may be generalizable to other clinical settings are most desirable.

1. Background. Provide relevant background information and literature review that led to the development of the bedside teaching tip.

2. Explanation. Explain the technique in detail, including the roles of all persons involved (teacher, learner, patient, other team members, etc.).

3. Description. Describe the outcomes realized by implementing the technique. These may include (but are not limited to) change in learner engagement, patient satisfaction, reduction of medical error, improved teamwork, etc.

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1. National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine . A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frist WH. Overcoming disparities in U.S. health care. Health Aff 2005;24:445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Givens M, Gennuso K, Jovaag A, Van Dijk JW. County Health Rankings Key Findings Report 2017. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hardeman RR, Burgess D, Phelan S, Yeazel M, Nelson D, van Ryn M. Medical student socio‐demographic characteristics and attitudes toward patient centered care: do race, socioeconomic status and gender matter? A report from the Medical Student Changes study. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:350–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. AAMC . Medical students’ socioeconomic background and their completion of the first two years of medical school. Anal Brief 2010;9(11). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Youngclas J, Fresne JA. Physician Education Debt and the Cost to Attend Medical School 2012 Update. Washington, DC: AAMC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fornari A, Anderson M, Simon S, Korin E, Swiderski D, Strelnick AH. Learning social medicine in the Bronx: an orientation for primary care residents. Teach Learn Med 2011;23:85–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crandall SJ, Reboussin BA, Michielutte R, Anthony JE, Naughten MJ. Medical students’ attitudes toward underserved patients: a longitudinal comparison of problem‐based and traditional medical curricula. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2007;12:71–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education . Advancing Education in Practice‐Based Learning and Improvement: An Educational Resource From the ACGME Outcome Project Available at: http://www.acgme.org/outcome/implement/complete PBLIBooklet.pdf. Accessed Oct 20, 2017.

- 10. Counsel of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors. 2013 Model Curriculum Available at: https://www.cordem.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageID=3635. Accessed Oct 10, 2017.

- 11. Axelson DJ, Still MJ, Coates WC. Social Determinants of Health: A Missing Link in Emergency Medicine Training. AEM Education and Training Early View. Available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10056/abstract. Accessed Oct 22, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. Primary Care Pediatrics. Oakland, CA: Children's Hospital of Oakland, 2017. Available at: https://www.childrenshospitaloakland.org/main/pediatric-residency-departments.aspx. Accessed Aug 14, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Community Pediatrics and Advocacy Rotation. Los Angeles, CA: Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, 2017. Available at: https://www.chla.org/community-pediatrics-and-advocacy-rotation. Accessed Aug 14, 2017. [Google Scholar]