Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the most lethal cancers in the world. The fight against breast cancer has also become a major task for medical workers. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are often aberrantly expressed in diverse cancers and are involved in progression and metastasis. Many studies have found that miRNAs can act as oncogenes or as tumor suppressor genes. Here, we show that miR-433 is significantly decreased in breast cancer cells. In addition, we demonstrate the effects of miR-433 on breast cancer cell apoptosis, migration and proliferation in an attempt to elucidate the mechanism of action of miR-433. Moreover, Rap1a was predicted to be a potential target of miR-433 using bioinformatic approaches, and we found that the expression of Rap1a is inversely correlated with the level of miR-433. Further studies through overexpression and knockdown of Rap1a confirmed that Rap1a, as a direct target gene of miR-433, contributes to the functions of miR-433. In addition, we found that Rap1a activates the MAPK signaling pathway, which can contribute to cell migration and proliferation and can inhibit apoptosis. Overall, these findings highlight miR-433 as a tumor suppressor gene in the regulation of the progression and metastatic potential of breast cancer and may benefit the future development of therapies targeting miR-433 in breast cancer.

Keywords: miR-433, breast cancer, Rap1a, MAPK, proliferation, apoptosis

Introduction

Breast cancer is the world's most common cancer among women and the second most common cause of cancer-related mortality in women1. Breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease because of its complex etiology, which includes many environmental factors and genetic alterations that cause cellular process changes; thus, breast cancer patients will show a range of clinical behaviors and different pathological entities2, 3. The current treatment strategies for breast cancer have adverse side effects, such as chemotherapy, which cannot distinguish between normal and cancer cells; thus, breast cancer is considered incurable, and the goal of therapy is to prolong the patient's survival time. There is thus an urgent need to understand the biological mechanisms underlying breast cancer and to develop novel, effective strategies for the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of breast cancer.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small noncoding RNAs of ~23 nucleotides that are thought to modulate the expression of at least 30% of all human protein-coding genes by specifically binding to the 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR) of the target mRNA4, 5. Endogenous miRNAs exert their effects on the base-pairing of the target mRNA gene 3'-UTR with the seed region of the miRNA (nucleotides 2-8 from its 5' end)6. Although the number of miRNAs is small, miRNAs are powerful regulators of complex processes, such as development, cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation and metabolism. This is mainly due to imperfect complementary miRNAs and their target genes; each miRNA may possess >100 targets7-10. An increasing number of studies have shown that aberrant miRNA expression participates in many diseases, including a variety of cancers11, 12. Breast cancer is one of these cancers, and miRNA may function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors13, 14. Therefore, as a key factor in signaling cascades, miRNAs are a potentially useful biomarker for clinical diagnosis and may serve as both a target and a tool in cancer therapy development15.

Rap1 is a small G protein of the Ras guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) superfamily and is important in cell motility junction formation16, 17. Rap1A is one of the two isoforms of Rap1 (Rap1a and Rap1b) that are expressed in mammals18. Serving as a GTPase, Rap1 acts as a molecular switch by alternating between an inactive GDP-bound and an active GTP-bound state. Previous reports have elaborated that Rap1a is involved in various essential cellular processes, such as proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation and survival19. Rap1 has been found to regulate the p38/AKT/ERK pathway to exert its effect20, 21. The MAPK pathway plays a critical role in many aspects of tumorigenesis and development by being involved in the regulation of cancer cell processes, such as growth, proliferation, survival, migration and apoptosis22. However, the mechanism of the Rap1a/MAPK axis in breast cancer is unclear.

In the present study, the expression of miR-433 in breast cancer was evaluated, and the potential role of miR-433 in breast cancer cell lines was investigated. Cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis were detected in miR-433 overexpression and knockdown models. In a further study, we demonstrated Rap1a to be a direct target gene of miR-433. Moreover, we evaluated the possible underlying mechanisms of Rap1a in breast cancer and tested its downstream factors.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cultures

The 4T1 cells used in this study were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences cell bank (Shanghai, China), and the MCF-7 and human HEK293 cells were purchased from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA). All cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2.

RNA extraction and qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from the tissue and cell lines using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The total RNA was treated with DNase I and reverse transcribed into cDNA. The expression levels of miRNA were assessed using a Hairpin-itTM microRNA qPCR Quantitation Kit (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) according to the standard protocol. The expression of U6 was used as an endogenous control. The total cDNA was used as the starting material for real-time PCR with FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) using the StepOne real-time PCR System (Life Technologies Corp. Waltham, MA, USA). The Primer Premier software (PREMIER Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used to design specific primers for miR-433-3p, Rap1a and GAPDH based on known sequences (Table 1). The expression levels of each target gene were normalized to the corresponding GAPDH or U6 threshold cycle (CT) values using the 2-△△CT comparative method.

Table 1.

Primer sequence for qPCR

| Gene | Primer sequence(5'-3') | product size(bp) |

|---|---|---|

| Rap1a | Forward:CAAGCTAGTAGTCCTTGGTTCAG | 106 |

| Reverse:GGAATCTTCTATCGTTGGGTCAT | ||

| GAPDH | Forward:AACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTC | 111 |

| Reverse:CCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTATT | ||

| miR-433 | Stem-loop:CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATTCAGTTGAGacaccgag | |

| Forward:TCGGCAATCATGATGGGCTCCTC | ||

| Reverse:CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTC | ||

| U6 | Stem-loop:CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATTCAGTTGAGcaatcagc | |

| Forward:CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA | ||

| Reverse:AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

Transient transfection (Transfections of miRNA and small interfering RNA (siRNA))

Oligonucleotide miR-433 mimics, inhibitors, Rap1a siRNA and their respective negative control oligonucleotides were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Overexpression of Rap1a in cells was achieved via transfection with a Rap1a ORF expression clone (GeneCreate, Wuhan, China). The 4T1 and MCF-7 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates at a density of 2×105 cells/ml per well. Then, the cells were washed once with prewarmed (37°C) serum-reduced Opti-MEM I medium (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The transfection of the miR-433 mimic/ inhibitor or miR-control involved 0.4 ml of Opti-MEM at a final concentration of 100 nM and 10 µg/ml Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA, USA) per well. The cells were incubated for 6 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Subsequently, the transfection medium was replaced with complete medium containing 10% FBS.

Cell proliferation assay

The 4T1 and MCF-7 cells were seeded on 96-well plates at a density of 6.0×103 cells/well. The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo Laboratories, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan) was used to assess cell proliferation. After being transfected with miR-433 mimics, miRNA-inhibitor, and their respective negative controls for 24 h, 48 h and 72 h, the cells were continuously cultured with 10 μL of CCK-8 in each well at 37°C for 2 h. Cell proliferation was measured by absorbance (optical density) with a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Instruments, Hercules, CA, USA) at 450 nm. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Cell migration assay

A wound healing assay was used to assess cell migration. As a previously described method in a study23, the 4T1 and MCF-7 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates and were transfected with siRNA, miR-433 mimics, miR-433 inhibitor, and their respective negative controls, as described in the figure legends using Lipofectamine 2000. After the cells were almost covered, wounding was accomplished by dragging a 200 μL pipette tip through the monolayer. After washing the cells two times, the wound closures were photographed when the scrape wound was introduced (0 h) and at a designated time (24 and 48 h) using an inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation, CKX41, Japan). The assay was independently repeated three times.

Cell apoptosis analysis

The effect of miR-433 on cell apoptosis was determined using flow cytometry. Briefly, the cells were seeded onto 6-well plates overnight and transfected, and the cells were then harvested and washed twice in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were stained using the Annexin-V-PI apoptosis detection kit (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NH, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and they were analyzed by FACS (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Western blot analysis

The total protein of the tissue and cells was extracted according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Samples with equal amounts of protein (50 μg) were fractionated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST for 1.5 hat 25°C. The membranes were then incubated at 4°C overnight with 1:1000 dilutions (v/v) of the primary antibodies. This study used Rap1a, a MAPK pathway sampler kit, MMP-9 antibodies purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA), and caspase-3, caspase-9 and PARP1 antibodies purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). After washing the membranes with TBST, incubations with 1:4000 dilutions (v/v) of the secondary antibodies were conducted for 2 hrs at 25°C. Protein expression was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Plasmid construction and cell transfection

To confirm the possibility of miR-433 targeting the predicted candidate gene, the 3'-untranslated region (UTR) of Rap1a containing the miR-433 binding site was inserted into the Xba I and Sac I sites of the pGL3 promoter vector. Mutant Rap1a containing single-mutated and double-mutated base sites were constructed using a fast mutagenesis kit. The 293T cells were plated onto 6-well plates at a density of 4×105 cells/ml per well and cotransfected with pGL3‑Rap1a or pGL3‑Rap1a‑MUT and miR‑433 mimics using Lipofectamine 2000.

Dual luciferase assays

Forty-eight hours after transfection, the luciferase activity was assessed using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay kit (Promega, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. In addition, luminescence intensity was read with a microplate luminometer following the manufacturer's protocol. The relative luciferase activity levels were determined by normalizing the levels to the activity of Renilla luciferase. Transfections were performed in duplicate and were repeated three times.

Immunofluorescence staining

After the 4T1 and MCF-7 cell lines were transfected with miR-433 mimics or si-Rap1a in 6-well-plates, the cells were collected onto slides and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Immunofluorescence staining was performed. The cells were incubated with special antibody for p-p38/pERK (1:100) overnight at 4°C and then incubated with secondary antibody in the dark for 2 h at 25°C. Next, the p-p38/pERK protein was mounted using a mounting medium supplemented with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Beyotime, China) for nuclear counterstaining, and the protein was observed using fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Japan).

In vivo experiment

Six- to eight-week-old BALB/C female mice were purchased from the Hubei Provincial Center for Experimental Animal Research (Wuhan, China). The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee for Animal Care and Use of Huazhong Agricultural University and was in line with the United States National Institutes of Health's published experimental animal care and use guide. All mice were fed a standard diet and were housed in a temperature-controlled room with a 12-h dark/light cycle for one week prior to the experiments. There were approximately 1.0×107 4T1 cells without any contamination that were harvested, suspended in 200 μL of PBS and then subcutaneously injected into each mouse's fourth breast pad. One month later, 15 mice were randomly selected, and allogeneic xenograft samples and paratumor tissue were collected.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the means ± (SEM) from at least three separate experiments. Multiple group comparisons were performed with two-tailed Student's t-tests, and P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The expression of miR-433 was significantly reduced in breast cancer cells and tissue

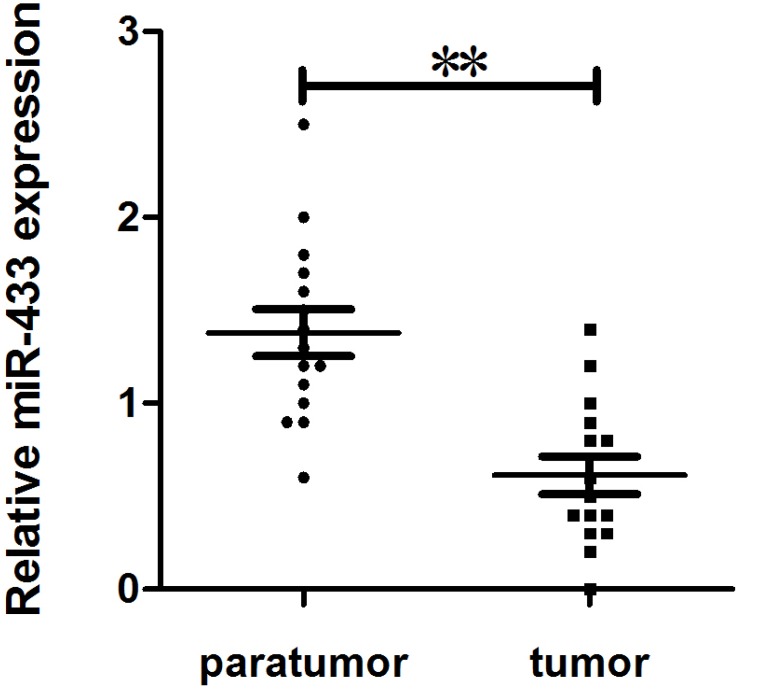

To explore the potential role of miR-433 in breast cancer, we collected 15 mammary gland homotransplants with their adjacent tissue from female Balb/c mice. To evaluate the expression of miR-433 using quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qPCR). As shown in Figure 1, the expression of miR-433 in breast cancer was obviously reduced.

Figure 1.

Expression of miR-433 in breast cancer specimens. Comparison of miR-433 expression in 15 paired tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues using qRT-PCR. These specimens were collected in homotransplants from Balb/c female mice. The experiments were performed three times. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. The symbol ** denotes a significant difference of P< 0.01.

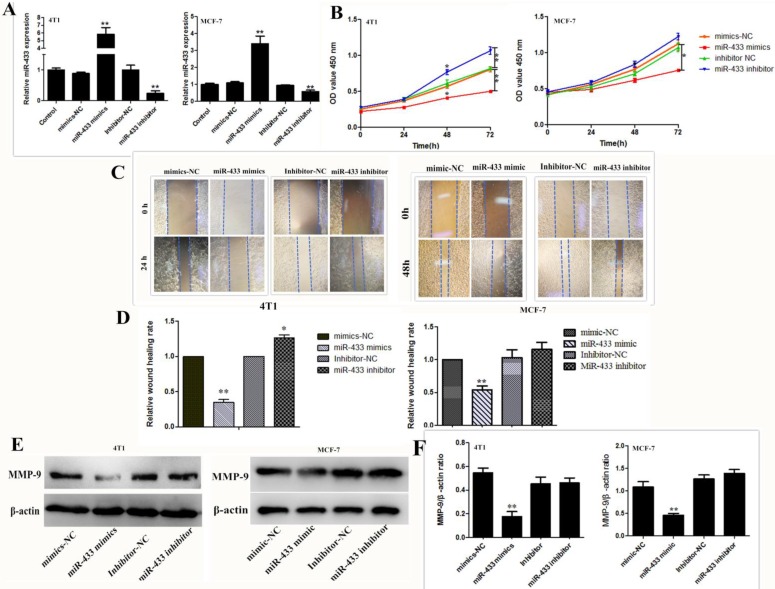

MiR-433 affected cell viability, migration and invasion in breast cancer cells

To investigate the effect of miR-433 on breast cancer cell viability, invasion and migration, the miR-433 mimic and inhibitor were transfected into the 4T1 and MCF-7 cells. Transfection efficiency was validated by using RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 2A, the expression level of miR-433 was significantly increased in the miR-433 mimics group; however, miR-433 expression was reduced in cells transfected with the miR-433 inhibitor. The results of the cell proliferation assay indicated that compared with the control, overexpression of miR-433 significantly inhibited cell proliferation (Figure 2B). Similarly, the wound scraping assay indicated miR-433 inhibitor cell migration (Figure 2C and D). MMP-9 is a well-known matrix metalloproteinases proteinase (MMPs) that disrupts the extracellular matrix (ECM), which induces the invasion of cancer cells; thus, it has been widely studied as a major target of cancer metastasis24-26. In the present study, we assessed the ability of cells to invade by measuring the expression of MMP-9. The level of MMP-9 was clearly lower in the cells transfected with miR-433 mimics than it was in the control (Figure 2E and F). To conclude, miR-433 is an important element that can help inhibit breast cancer development.

Figure 2.

High expression of mir-433 inhibited cell proliferation, migration and invasion. A. The expression levels of miR‑433 in 4T1 and MCF-7 cells transfected with mimics-NC, miR-433 mimics, inhibitor-NC and miR-433 inhibitor were detected using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reactions. B. CCK-8 were used to assess the proliferation of 4T1 and MCF-7 cells transfected with oligonucleotides at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. C, D. Wound healing assays of 4T1 and MCF-7 cells after transfection with miR-NC, miR-433 mimics, inhibitor-NC and miR-433 inhibitor. Representative images depicting the beginning (t = 0 h) and the end (t = 24 h) of the recording period are shown. E, F. The protein expression levels of MMP-9 were detected using western blots. β-actin was used as the control. All results are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. The symbols * and ** denote significant differences of P<0.05 and P< 0.01, respectively.

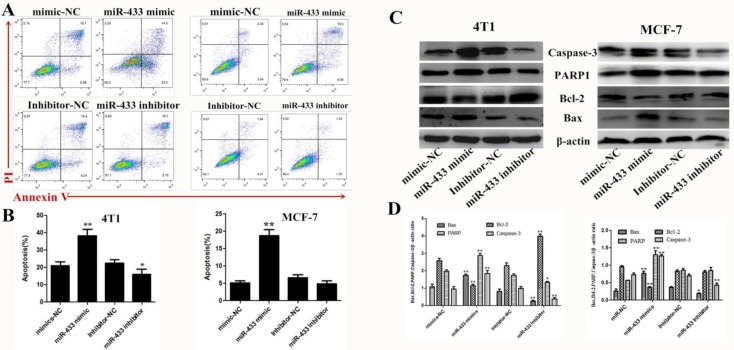

Overexpression of miR-433 induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells

There is no doubt that induced apoptosis is the most effective treatment strategy for breast cancer. Therefore, using flow cytometry, we confirmed that miR-433 induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells compared with the NC group transfected with miRNA (Figure 3A and B). Then, expression of the apoptosis-related protein was measured by western blot, such as caspase-3, PARP1, Bax and Bcl-2 (Figure 3C and D). The results indicated that miR-433 increased pro-apoptosis protein expression and decreased anti-apoptosis protein expression, while the opposite occurred in the miR-433 inhibitor group. In summary, miR-433 is consistent with a tumor-suppressive function for this miRNA in 4T1 and MCF-7 cells.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of miR-433 induced apoptosis in 4T1 and MCF-7 cells. A, B. Cell apoptosis assays of 4T1 and MCF-7 cells treated with NC, miR-433 mimics, inhibitor-NC or miR-433 inhibitor using FACS. Cells were collected and labeled with Annexin V-FITC and PI. C, D. Western blot analyses of caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2 and PARP1 treated with NC, miR-433 mimics, inhibitor-NC or miR-433 inhibitor. β-actin was used as an internal control. All results are expressed as the mean± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. The symbols * and ** denote significant differences of P<0.05 and P< 0.01, respectively.

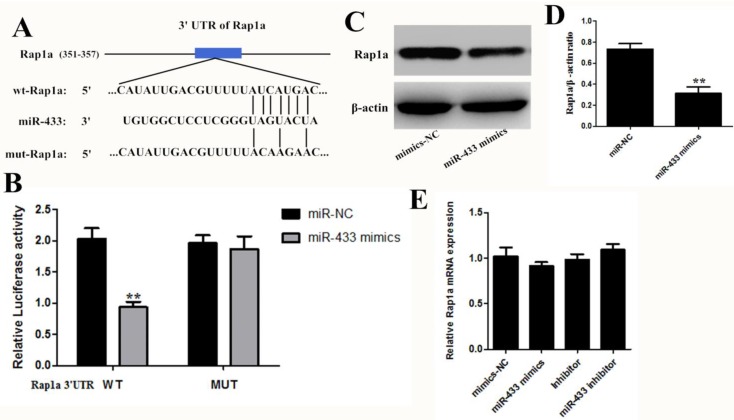

Rap1a is a direct target of miR-433

To further reveal the mechanism of miR-433, we first identified the target gene of miR-433. Bioinformatic analysis is the main research method used for screening miRNA target genes, so we compared the results obtained from different searches, such as TargetScan, miRDB, and the miRanda algorithms. The results predicted Rap1a as a target of miR-433 and predicted a possible binding region of miR-433 in the 3' untranslated region (3'-UTR) of Rap1a (Figure 4A). Then, we used a dual luciferase experiment to verify the targeting effect relationship. As shown in Figure 4B, in the cotransfected miR-433 mimics, the PGL-3-Rap1a-3'UTR plasmid 293T cells, the luciferase activity significantly decreased compared with the other group. However, the cotransfected PGL-3-mut-Rap1a-3'UTR and the mimics scramble or miR-433 mimics did not affect the luciferase activity, and their luciferase activities did not display any significant differences compared with the control. In addition, the expression of Rap1a at the protein level was decreased in the transfected with miR-433 mimics cell group in 4T1 (Figure 4C and D). However, the expression of Rap1a at the mRNA level did not change significantly (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Rap1a is a gene target of miR-433. A. Schematic of predicted miR-433 binding sites in the Rap1a-3′UTR. B. The pmirGLO-3 reported plasmids, those containing the 3'-UTRs of the wild-type Rap1a mRNA or those with a 3'-UTR with mutated miR-433-binding sites were cotransfected along with miR-433 mimics or mimics-NC into HEK293T cells, after 24 h of which, the luciferase activity was measured using the dual luciferase reporter assay system. C, D. The protein expression levels of Rap1a in the 4T1 cells transfected with miR-433 mimics were determined using western blot. β-actin was used as an internal control. E. The mRNA expression levels of Rap1a were detected in 4T1 cells transfected with miR-433 using qRT-PCR. All results are expressed as the mean± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. The symbol ** denotes a significant difference of P< 0.01.

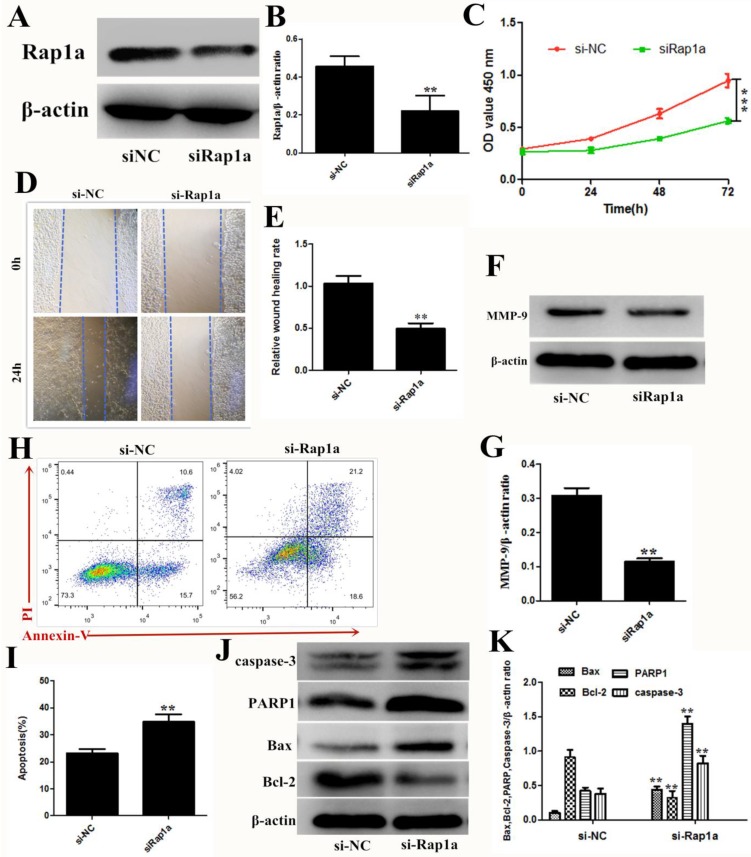

The effect of knockdown Rap1a is consistent with the overexpression of miR-433

To elucidate the role of Rap1a in 4T1 cells, we detected the cell viability, proliferation, and apoptosis after siRNA knockdown of Rap1a. Targeting Rap1a with siRNA decreased Rap1a protein expression in 4T1 cells (Figure 5A and B), and significant reductions in cell proliferation, invasion and migration were observed with the transfection of siRNA against Rap1a mRNA (Figure 5C-G). Flow cytometric analysis and western blot assays also revealed a high proportion of apoptotic cells after transfection of Rap1a siRNA (Figure 5H and K). These data suggested that Rap1a is a functional target of miR-433.

Figure 5.

Rap1a is a functional target of miR-433. A, B. The protein expression levels of Rap1a in si-Rap1a transfected 4T1 cells were determined using Western blot. β-actin was used as an internal control. C. CCK-8 were used to assess the proliferation of 4T1 cells transfected with si-Rap1a at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. D, E. Wound healing assays of 4T1 cells after transfection with si-Rap1a. Representative images depicting the beginning (t = 0 h) and the end (t = 24 h) of the recording period are shown. F, G. The protein expression levels of MMP-9 were detected using western blot. H, I. Cell apoptosis assays of 4T1 cells treated with si-Rap1a using FACS. J, K. Western blot analyses of caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2 and PARP1 treated with si-Rap1a. β-actin was used as an internal control. All results are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. The symbols ** and *** denote significant differences of P<0.01 and P< 0.001, respectively.

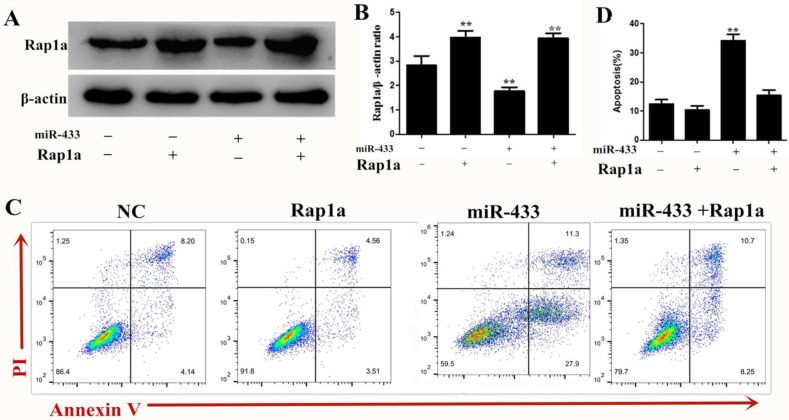

Overexpression of Rap1a partially rescued the induced apoptosis effect of miRNA-433 on breast cancer cells

To investigate the role of Rap1a in the miRNA-433-mediated inhibition of breast cancer cell apoptosis, 4T1 cells were transfected with miRNA-433 mimics or mimic-NC for 24 h and were subsequently transfected with Rap1a ORF clone or empty vector (pcDNA3.1(+)) for another 24 h. Western blots showed that the transfection with the Rap1a ORF clone significantly increased the Rap1a protein level compared with the control group, while cotransfection with miRNA-433 mimics + Rap1a ORF clone significantly restored the expression of Rap1a compared with the miR-433 mimic + pcDNA3.1(+) group (Figure 6A). As expected, we found that the overexpression of Rap1a significantly rescued the induced apoptosis effect of miRNA-433 on breast cancer cells (Figure 6B). Overall, these data suggested that the overexpression of Rap1a could rescue the effect of miRNA-433 induced breast cancer cell apoptosis.

Figure 6.

overexpression Rap1a can reverse the effect of miR-433 induced apoptosis. A, B. The protein expression level of Rap1a in Rap1a ORF clone transfected 4T1 cells were determined using Western blot. β-actin was used as an internal control. C, D. Cell apoptosis assays of 4T1 cells treated with Rap1a ORF cDNA clone expression plasmid using FACS. All results are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. The symbols ** denote significant differences of P< 0.01.

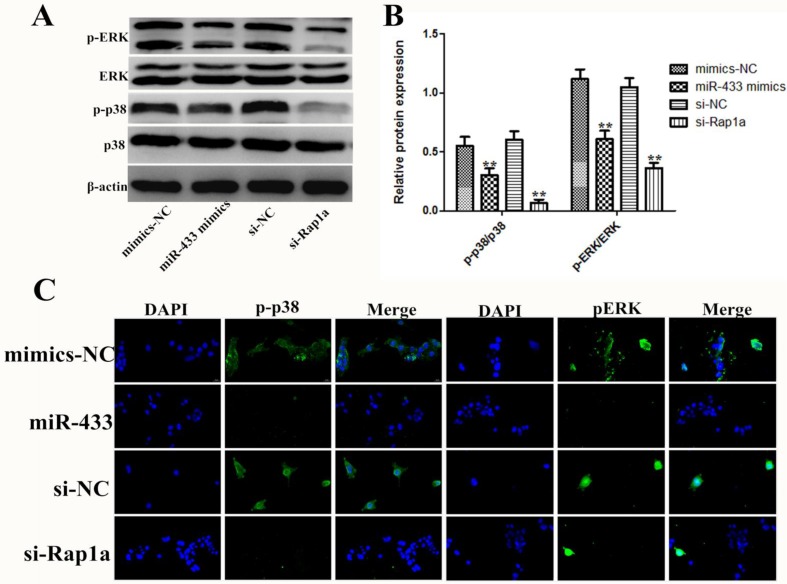

The effect of miR-433 is partially dependent on the MAPK signal pathway

As described above, Rap1a is a direct target gene of miR-433, but the mechanism of the effect of Rap1a still needs to be studied in 4T1 cells. Previous studies have shown that Rap1a, similar to other small G proteins, can regulate multiple signaling pathways 27-29. In this study, we found that miR-433 inhibits the phosphorylation of p-p38 and pERK (Figure 7A and B). The results of the immunofluorescence also led to the same conclusion, in which miR-433 inhibited the activation of the MAPK signaling pathway (Figure 7C). In addition, the results indicated the reverse in silenced Rap1a in the presence of miR-433 inhibition.

Figure 7.

The effect of miR-433 on 4T1 cells was exerted through regulation of the MAPK signal pathway. A, B. After 4T1 cells were transfected with miR-433 mimics, si-Rap1a and the corresponding controls, the protein expression levels of p38, p-p38, ERK and pERK were detected by western blot. β-actin was used as an internal control. C. Immunofluorescence images showing transfection with miR-433 mimics or si-Rap1a inhibits p-p38 and pERK activation in 4T1 cells. All of the data represent the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. The symbol ** denotes a significant difference of P< 0.01.

Discussion

Breast cancer patients experience relapse after treatment, primarily because the traditional treatment strategies are less sensitive and specific, resulting in cancer cells being able to survive. This emphasizes the high demand for reasonable and systematic therapies. Over the past decade, miRNAs have emerged as a critical factor in various cellular processes 30-32. An accumulating number of studies have indicated miRNA as salient regulators of cancer progress and have considered them novel diagnostic tools and valuable therapeutics33. Here, in this study, we demonstrated that miR-433 is downregulated in breast cancer cell lines and tissue using qRT-PCR. Then, we conjectured that miR-433 exerts an important effect on the development of breast cancer. To confirm this hypothesis, we established miR-433 overexpression and knockdown models in breast cancer cell lines. In a further study, we indicated that overexpression of miR-433 significantly attenuated breast cancer cell migration and proliferation and that this overexpression induced apoptosis.

The miRNAs are divided into two main types in cancer: oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, and miRNAs have been shown to be differentially expressed in different types of cancer, meaning that one miRNA has different functions in different tissues. Previous studies mostly defined miR-433 as an oncogene. As in ovarian cancer, miR-433 induced cellular senescence by disrupting cell cycle progression34. In gastric cancer cells, miR-433 targets KRAS to inhibit cell migration and proliferation in vitro35. In colorectal cancer, the upregulation of miR-433 was able to reduce viability and promote apoptosis by downregulating MACC136. In hepatocellular carcinoma, miR-433 is a potent inhibitor of HCC cell proliferation by targeting PAK415, GRB2 and HDAC637. However, the mechanism of miR-433 in breast cancer remains unclear. In this study, we demonstrated that the aberrant expression of miR-433 is involved in the progression of breast cancer. Because one miRNA can control multiple genes by binding to the 3′-UTRs of target mRNAs, the combined biological effects are largely influenced by the specific genetic background of the types of cells or tumors in which the miRNA is expressed38. Thus, the seemingly distinct functions of miR-433 in different types of cancer reflect the intrinsic complexities and diversities of tumor biology. In this study, we found that the miR-433 expression levels were significantly reduced in breast cancer and that the overexpression of miR-433 inhibited cell proliferation and migration and induced apoptosis.

To further investigate the mechanism of miR-433 in breast cancer, we searched for miR-433 potential target genes using a variety of bioinformatic methods. The genes that were predicted by all the algorithm programs we used (TargetScan, miRDB and miRanda) were selected as the candidate targets. The candidate target gene Rap1a was confirmed as a direct target of miR-433 using dual fluorescein reporter assays. Rap1a, a member of the RAS oncogene family, has been shown to demonstrate aberrant expression in multiple malignant tumors39. As mentioned before, Rap1a has been implicated in the processes of cell division, proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation. However, a previous study suggested the efficacy of Rap1a in cell and/or environment-specific contexts40. Recent evidence suggested that knocking down Rap1a can sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy and then regulate the prognoses of cancer patients, such as in lung cancer41. In prostate cancer, activation of Rap1 promotes metastasis42. There is a consensus from studies of several kinds of cancer that the over-activation of Rap1 induces cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis43, 44. In the present study, we found that knockdown of Rap1a inhibited cell proliferation and invasion and induced apoptosis, and overexpression of Rap1a partially rescued the induced apoptosis effect of miRNA-433 on breast cancer cells. These findings all indicated that Rap1a is a functional target of miR-433, and this evidence suggested that miR-433 exerts its tumor-suppressive effects through the downregulation of Rap1a in breast cancer cells.

In addition, we noted that miR-433 overexpression decreased the levels of proteins related to the MAPK pathway, and this function of miR-433 could act directly or indirectly through this pathway. A further study showed that Rap1a silencing could phenocopy the regulatory effects of miR-433 on the MAPK pathway. Interestingly, since Rap1 was first identified, the relationship between the ras/ERK signaling and the effect of Rap1 on cell proliferation has been closely examined45. Currently, Rap1 is thought to participate in many cellular processes by mediating the MAPK pathway, which has been demonstrated in a variety of cell types46-48. The results of the present study indicated that miR-433 silences Rap1a, thereby inhibiting the MAPK signaling pathway, in its role as a tumor suppressor gene.

Briefly, we identified miR-433 as a tumor suppressor gene in breast cancer and Rap1a as a novel functional target of miR-433. The functions of miR-433 include suppressing cell proliferation, migration and invasion and inducing apoptosis via inactivation of the MAPK signaling pathway. All of these data revealed a novel tumor-suppressing mechanism in breast cancer, indicating that miR-433 may serve as a diagnostic and potential therapeutic target in breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Major Project for Breeding of Transgenic Pig (2016ZX08006-002), and the Cooperative Innovation Center for Sustainable Pig Production.

Contributions

T.Z., K.J., and G.D.,C.Q. conceived and designed the experiments. T.Z., K.J., G.Z., X.Y, H.W., and C.Q. performed the experiments. T.Z., K.J., H.W., and C.Q. analyzed the data. T.Z., K.J., G.D., and C.Q. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- miR-433

microRNA-433, CCK-8: Cell Counting Kit-8, Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma-2, FACS: Fluorescence activated cell sorting, MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase, ERK: extracellular regulated protein kinase, qRT-PCR: quantitative Real-time RT-PCR (Reverse Transcription-PCR).

References

- 1.Anderson BO, Lipscomb J, Murillo RH, Thomas DB. Breast Cancer. In: Gelband H, Jha P, Sankaranarayanan R, Horton S, editors. Cancer: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 3) Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank (c) 2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bombonati A, Sgroi DC. The molecular pathology of breast cancer progression. The Journal of pathology. 2011;223:307–17. doi: 10.1002/path.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reis-Filho JS, Lakhani SR. The diagnosis and management of pre-invasive breast disease: genetic alterations in pre-invasive lesions. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2003;5:313–9. doi: 10.1186/bcr650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shukla GC, Singh J, Barik S. MicroRNAs: Processing, Maturation, Target Recognition and Regulatory Functions. Molecular and cellular pharmacology. 2011;3:83–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inui M, Martello G, Piccolo S. MicroRNA control of signal transduction. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2010;11:252–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wahid F, Shehzad A, Khan T, Kim YY. MicroRNAs: synthesis, mechanism, function, and recent clinical trials. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2010;1803:1231–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yanaihara N, Caplen N, Bowman E, Seike M, Kumamoto K, Yi M. et al. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer cell. 2006;9:189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhan MN, Yu XT, Tang J, Zhou CX, Wang CL, Yin QQ. et al. MicroRNA-494 inhibits breast cancer progression by directly targeting PAK1. Cell death & disease. 2017;8:e2529. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schickel R, Boyerinas B, Park SM, Peter ME. MicroRNAs: key players in the immune system, differentiation, tumorigenesis and cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:5959–74. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heyn H, Engelmann M, Schreek S, Ahrens P, Lehmann U, Kreipe H. et al. MicroRNA miR-335 is crucial for the BRCA1 regulatory cascade in breast cancer development. International journal of cancer. 2011;129:2797–806. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavazoie SF, Alarcon C, Oskarsson T, Padua D, Wang Q, Bos PD. et al. Endogenous human microRNAs that suppress breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2008;451:147–52. doi: 10.1038/nature06487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trang P, Weidhaas JB, Slack FJ. MicroRNAs as potential cancer therapeutics. Oncogene. 2008;27(Suppl 2):S52–7. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu H, Guo X, Zou L, Zhu H, Zhang J. Upregulation of microRNA-372 associates with tumor progression and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2013;375:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1521-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue J, Chen LZ, Li ZZ, Hu YY, Yan SP, Liu LY. MicroRNA-433 inhibits cell proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting p21 activated kinase (PAK4) Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2015;399:77–86. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boettner B, Van Aelst L. Control of cell adhesion dynamics by Rap1 signaling. Current opinion in cell biology. 2009;21:684–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Jiang Y, Shi D, Quilliam LA, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Wittchen ES. et al. Activation of Rap1 inhibits NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS generation in retinal pigment epithelium and reduces choroidal neovascularization. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2014;28:265–74. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-240028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu A, Chen H, Xu C, Zhou J, Chen S, Shi Y. et al. miR-203a is involved in HBx-induced inflammation by targeting Rap1a. Experimental cell research. 2016;349:191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gloerich M, Bos JL. Regulating Rap small G-proteins in time and space. Trends in cell biology. 2011;21:615–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu L, Wang J, Wu Y, Wan P, Yang G. Rap1A promotes ovarian cancer metastasis via activation of ERK/p38 and notch signaling. Cancer medicine. 2016;5:3544–54. doi: 10.1002/cam4.946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JY, Juhnn YS. cAMP signaling increases histone deacetylase 8 expression via the Epac2-Rap1A-Akt pathway in H1299 lung cancer cells. Experimental & molecular medicine. 2017;49:e297. doi: 10.1038/emm.2016.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song G, Zhang Y, Wang L. MicroRNA-206 targets notch3, activates apoptosis, and inhibits tumor cell migration and focus formation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:31921–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orgaz JL, Pandya P, Dalmeida R, Karagiannis P, Sanchez-Laorden B, Viros A. et al. Diverse matrix metalloproteinase functions regulate cancer amoeboid migration. Nature communications. 2014;5:4255. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chabottaux V, Noel A. Breast cancer progression: insights into multifaceted matrix metalloproteinases. Clinical & experimental metastasis. 2007;24:647–56. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nature reviews Cancer. 2002;2:161–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, Fotheringham L, Wittchen ES, Hartnett ME. Rap1 GTPase Inhibits Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha-Induced Choroidal Endothelial Migration via NADPH Oxidase- and NF-kappaB-Dependent Activation of Rac1. The American journal of pathology. 2015;185:3316–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teo H, Ghosh S, Luesch H, Ghosh A, Wong ET, Malik N. et al. Telomere-independent Rap1 is an IKK adaptor and regulates NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression. Nature cell biology. 2010;12:758–67. doi: 10.1038/ncb2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Y, Zhou J, Li Y, Zhou Y, Cui Y, Yang G. et al. Rap1A Regulates Osteoblastic Differentiation via the ERK and p38 Mediated Signaling. PloS one. 2015;10:e0143777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai YH, Liu H, Chiang WF, Chen TW, Chu LJ, Yu JS, Chen SJ, Chen HC, Tan BCM. MiR-31-5p-ACOX1 Axis Enhances Tumorigenic Fitness in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Via the Promigratory Prostaglandin E2. Theranostics. 2018;8(2):486–504. doi: 10.7150/thno.22059. doi:10.7150/thno.22059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Wen S, Yao X, Liu W, Shen J, Deng W. et al. MicroRNA-378 protects against intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury via a mechanism involving the inhibition of intestinal mucosal cell apoptosis. Cell death & disease. 2017;8:e3127. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo J, Yang Z, Yang X, Li T, Liu M, Tang H. miR-346 functions as a pro-survival factor under ER stress by activating mitophagy. Cancer letters. 2018;413:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kota J, Chivukula RR, O'Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Montgomery CL, Hwang HW. et al. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell. 2009;137:1005–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiner-Gorzel K, Dempsey E, Milewska M, McGoldrick A, Toh V, Walsh A. et al. Overexpression of the microRNA miR-433 promotes resistance to paclitaxel through the induction of cellular senescence in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer medicine. 2015;4:745–58. doi: 10.1002/cam4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo LH, Li H, Wang F, Yu J, He JS. The Tumor Suppressor Roles of miR-433 and miR-127 in Gastric Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences. 2013;14:14171–84. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Mao X, Wang X, Miao G, Li J. miR-433 reduces cell viability and promotes cell apoptosis by regulating MACC1 in colorectal cancer. Oncology letters. 2017;13:81–8. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon D, Laloo B, Barillot M, Barnetche T, Blanchard C, Rooryck C. et al. A mutation in the 3'-UTR of the HDAC6 gene abolishing the post-transcriptional regulation mediated by hsa-miR-433 is linked to a new form of dominant X-linked chondrodysplasia. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19:2015–27. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long M, Zhan M, Xu S, Yang R, Chen W, Zhang S. et al. miR-92b-3p acts as a tumor suppressor by targeting Gabra3 in pancreatic cancer. Molecular cancer. 2017;16:167. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0723-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kometani K, Ishida D, Hattori M, Minato N. Rap1 and SPA-1 in hematologic malignancy. Trends in molecular medicine. 2004;10:401–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yajnik V, Paulding C, Sordella R, McClatchey AI, Saito M, Wahrer DC. et al. DOCK4, a GTPase activator, is disrupted during tumorigenesis. Cell. 2003;112:673–84. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du L, Subauste MC, DeSevo C, Zhao Z, Baker M, Borkowski R. et al. miR-337-3p and its targets STAT3 and RAP1A modulate taxane sensitivity in non-small cell lung cancers. PloS one. 2012;7:e39167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bailey CL, Kelly P, Casey PJ. Activation of Rap1 promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer research. 2009;69:4962–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao L, Feng Y, Bowers R, Becker-Hapak M, Gardner J, Council L. et al. Ras-associated protein-1 regulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and migration in melanoma cells: two processes important to melanoma tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cancer research. 2006;66:7880–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang L, Chenwei L, Mahmood R, van Golen K, Greenson J, Li G. et al. Identification of a putative tumor suppressor gene Rap1GAP in pancreatic cancer. Cancer research. 2006;66:898–906. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kitayama H, Sugimoto Y, Matsuzaki T, Ikawa Y, Noda M. A ras-related gene with transformation suppressor activity. Cell. 1989;56:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90985-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto A, Tanaka M, Takeda S, Ito H, Nagano K. Cilostazol Induces PGI2 Production via Activation of the Downstream Epac-1/Rap1 Signaling Cascade to Increase Intracellular Calcium by PLCepsilon and to Activate p44/42 MAPK in Human Aortic Endothelial Cells. PloS one. 2015;10:e0132835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorn A, Zoellner A, Follo M, Martin S, Weber F, Marks R. et al. Rap1a deficiency modifies cytokine responses and MAPK-signaling in vitro and impairs the in vivo inflammatory response. Cellular immunology. 2012;276:187–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stadtmann A, Brinkhaus L, Mueller H, Rossaint J, Bolomini-Vittori M, Bergmeier W. et al. Rap1a activation by CalDAG-GEFI and p38 MAPK is involved in E-selectin-dependent slow leukocyte rolling. European journal of immunology. 2011;41:2074–85. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]