Abstract

Objectives

In medical education and training, increasing numbers of institutions and learners are participating in global health experiences. Within the context of competency‐based education and assessment methodologies, a standardized assessment tool may prove valuable to all of the aforementioned stakeholders. Milestones are now used as the standard for trainee assessment in graduate medical education. Thus, the development of a similar, milestone‐based tool was undertaken, with learners in emergency medicine (EM) and global health in mind.

Methods

The Global Emergency Medicine Think Tank Education Working Group convened at the 2016 Society for Academic Medicine Annual Meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana. Using the Interprofessional Global Health Competencies published by the Consortium of Universities for Global Health's Education Committee as a foundation, the working group developed individual milestones based on the 11 stated domains. An iterative review process was implemented by teams focused on each domain to develop a final product.

Results

Milestones were developed in each of the 11 domains, with five competency levels for each domain. Specific learning resources were identified for each competency level and assessment methodologies were aligned with the milestones framework. The Global Health Milestones Tool for learners in EM is designed for continuous usage by learners and mentors across a career.

Conclusions

This Global Health Milestones Tool for learners in EM may prove valuable to numerous stakeholders. The next steps include a formalized pilot program for testing the tool's validity and usability across training programs, as well as an assessment of perceived utility and applicability by collaborating colleagues working in training sites abroad.

Increasing numbers of academic institutions and learners are participating in global health experiences.1, 2 These experiences are undertaken by undergraduates, medical students, residents, and fellows across all medical specialties. In emergency medicine (EM), 91% of residency programs offer global health rotations.3 In recent years, rapid expansion in both size and scope of global health programs has created challenges in many areas, including that of curriculum development. Authors have previously described the lack of standardization of curricula and competencies for learners in global health.4, 5 Numerous efforts have been undertaken to develop curricular frameworks and identify competencies in global health.6, 7 Prior consensus work has called for improved curricula and assessment methodologies for learners, specifically in the field of EM.8, 9, 10

Meanwhile, there is a movement in medical education toward competency‐based education, with an outcomes‐oriented focus.11, 12 Since 2015, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has adopted ACGME Milestones as a standard competency‐based tool for assessment across all specialties.13 These milestones are conceptually based on the progressive nature of learning and performance, illustrating the transition from student to independent practitioner consistent with the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition.14 Ideally, a similar model may be applied to learners in EM participating in global health experiences.

There is marked variability in the structure of global health experiences, ranging from clinical experiences to educational or research‐focused programs to public health programs in tremendously diverse settings around the globe. Participants in these experiences are also diverse in their baseline level of experience. All of these factors add significant complexity to the curriculum development and assessment process. However, we propose that all learners in EM who are participating in global health experiences should acquire a fund of knowledge, ranging from basic to advanced, which is standardized and measurable. Building on the milestones framework, the scope of learning may progress as learners continue to engage in global health experiences over time. Acknowledging the challenging nature of competency assessment in global settings, strategies include increased focus on self‐directed assessment and obtaining input from multiple stakeholders as foundational principles.15 Furthermore, we suggest that a standardized assessment tool will provide cohesion across experiences.

Methods

On May 10, 2016, a Global Emergency Medicine Think Tank was held in conjunction with the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) annual meeting to assess progress made in goals set during the 2013 consensus conference and to identify next steps for moving forward. The Education Working Group (EWG) was formed as a subgroup to focus on education specific issues identified in the 2013 SAEM consensus conference. The 19 members of the EWG include residents, fellows, and junior and senior faculty members from 13 U.S.‐based universities, representing a breadth of global health experience. All EWG members are currently active global health practitioners. Numerous issues were identified as priorities, including standardization of global health curriculum and methods of assessment. As a concrete effort to move forward, the EWG set out to develop “milestones” for global health experiences for learners in EM.

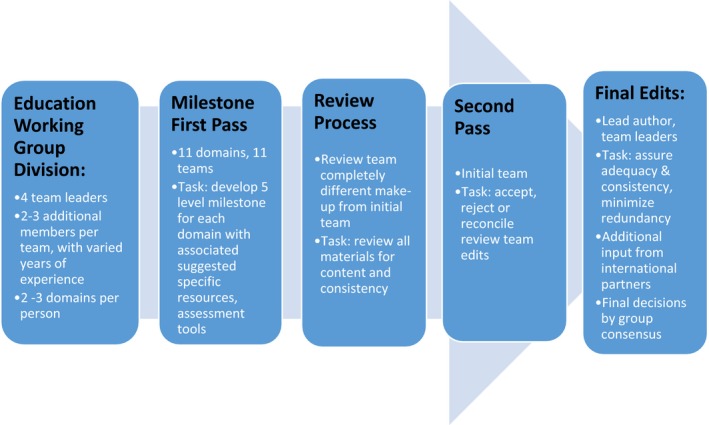

In 2015, the Consortium of Universities for Global Health's (CUGH) Subcommittee on Global Health Competency published a set of interprofessional global health competencies.6 The EWG used these competencies as a basis for milestone development as they cover the core/accepted domains of global health assessment. Given the variability of clinical exposure in global health experiences, focus was maintained on knowledge and professionalism issues (in line with the CUGH approach). The EWG divided into teams of three to four persons per domain to develop milestones, which consisted of five progressive levels per domain, with associated specific suggested resources for learning and assessment methods for each level. Specific suggested resources and assessment methods were identified by team members based on prior experience. A separate team subsequently reviewed each domain for content and consistency. A final comprehensive review was conducted to assure consistency and minimize redundancy across the domain, and final editing decisions were made by group consensus (see Figure 1). Additional feedback was sought from international partners regarding the content and format of the milestones.

Figure 1.

Process for milestone development and review.

Results

Milestones were developed for each of the CUGH domains (Table 1), based on progressive levels of learners from novice to expert. The complete milestones for each domain are listed in Table 2. While it is assumed that most learners will never achieve Level 5 in some or perhaps any of the domains, ideally individuals participating in global health experiences at a basic level will achieve the introductory levels in most domains. Specific suggested resources for learning were also identified for each of the milestone levels (see Table 3; also Data Supplement S1, available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at https://doi.org/onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10046/full). The assessment methods were aligned with each milestone as well, but then condensed into general guidelines given that we found generally applicability throughout (Table 4).

Table 1.

Consortium of Universities for Global Health Domains

| Domain 1 | Global burden of disease |

| Domain 2 | Globalization of health and health care |

| Domain 3 | Social and environmental determinants of health |

| Domain 4 | Capacity strengthening |

| Domain 5 | Collaboration, partnering, and communication |

| Domain 6 | Ethics |

| Domain 7 | Professional practice |

| Domain 8 | Health equity and social justice |

| Domain 9 | Program management |

| Domain 10 | Sociocultural and political awareness |

| Domain 11 | Strategic analysis |

Table 2.

Complete milestones for each domain

|

Domain 1: Global Burden of Disease Encompasses basic understandings of major causes of morbidity and mortality and their variations between high‐, middle‐ and low‐ income regions, and with public health efforts to reduce health disparities globally. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|

Describes the major causes of morbidity and mortality globally. Understands how the risk of disease varies with geographic location. Describes major trends in current disease prevalence. |

Describes the concept of epidemiological transition and its consequences. Understands historical context of health disparities and burden of disease. Describes major current and historical public health efforts to reduce disparities in global public health. |

Validates the health status of populations using available data. Understands the context in which population health data is collected. Analytically reviews epidemiologic research. |

Assesses population health data collection systems. Implements data collection systems. Participates in or contribute to population health research. |

Designs and implement systems for data collection in a sustainable and scalable manner. Leads interpretation and synthesis of data from various sources. Utilizes source data to produce summary documents and policy recommendations. |

|

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 2: Globalization of Health & Health care Focuses on understanding how globalization affects health, health systems, and the delivery of health care. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

| Understands different national models/systems for health care delivery. |

Describes how different health care systems impact health care outcomes and expenditures. Describes how global political and cultural events, commerce, and trade contribute to the spread of communicable and chronic diseases. |

Observes how different health care systems impact health care outcomes and expenditures. Observes how global political and cultural events, commerce, and trade contribute to the spread of communicable and chronic diseases. Describes general trends and influences in the global availability and movement of health care workers. |

Participates in multinational agreements (e.g. international assistance programs) and multinational organizations to contribute to the quality and availability of health and health care internationally. | Leads multi‐national agreements or multinational organizations to improve the quality of international health and health care. | |

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 3: Social and Environmental Determinants of Health Focuses on an understanding that social, economic, and environmental factors are important determinants of health, and that health is more than the absence of disease | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|

Demonstrates curiosity about cultural systems within communities and recognize how culture interacts with environment, economy, and politics to directly affect health. Demonstrates basic understanding of major social and cultural determinants of health and their effects on access to and quality of emergency care and other health services. |

Describes how cultural context influences perceptions of health and disease (e.g. cultural beliefs about basis of and remedies for disease, etc.). Recognizes how bias impacts the way patients think about health and disease. Demonstrates understanding of the major causes of morbidity and mortality between and within countries and identifies contributing social and environmental factors. |

Synthesizes available data to identify social, economic, and environmental determinants of health. |

Develops independent research to identify novel environmental, cultural, or societal determinants of health or further characterize known determinants. Contributes to culturally relevant programs or interventions to specifically address social and environmental factors affecting the health of global communities. |

Develops, advocates for, and implements policy recommendations or public health interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with social and environmental factors impacting the health and well‐being of global communities. Creates and disseminates curricula to teach trainees about social and environmental determinants of health |

|

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 4: Capacity Strengthening Capacity strengthening is sharing knowledge, skills, and resources for enhancing global public health programs, infrastructure, and workforce to address current and future global public health needs. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|

Understands host/partner organization's mission and can articulate it. Can define the meaning and importance of public health programs, infrastructure, and workforce. Defines the role and importance of community assets and resources that can be used to improve the health of individuals and populations. Demonstrates an understanding of the concepts of sustainability as it relates to capacity strengthening. |

Participates in host/partner organization's program and can articulate capacity at the level they are working (community‐based, district, region, or national). Understands and communicates the status of community capabilities and current health assets and disparities within the community. Participates in activities that facilitate the host/partner organization to utilize the community assets to benefit the population. |

Participates in host/partner organization's program and can identify strengths and deficiencies within the capacity at the level they are working. Identifies features that will make programs sustainable within their community and participate in activities that facilitate program sustainability. With partners, defines and applies strategies that can be used to strengthen community capabilities, reduce health disparities, and improve community health. |

Works with stakeholders to plan and implement assessments for operational capacity at the level they are working (community‐based, district, region, or national). Works with stakeholders to evaluate the impact of capacity development programs. Works with stakeholders to plan and assess impacts of activities that facilitate program sustainability. |

Coordinates with leadership of host/partner organization(s) to set up and evaluate collaborative programs/projects to grow operational capacity. Works with collaborating stakeholders to strategize and create an implementation plan and subsequent evaluation for activities that scale programs to broader implementation. Formalized policy change to include regional/national policies or laws that solidify the program implemented. |

|

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 5: Collaboration, Partnering and Communication Collaborating and partnering is the ability to select, recruit, and work with a diverse range of global health stakeholders to advance research, policy, and practice goals, and to foster open dialogue and effective communication with partners and within a team. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|

Identifies fundamental principles of communication which will enable effective collaboration and partnership in complex global health environments. Recognizes importance of locally driven problem solving, collaborative decision making, and fundamentals of partnership. Understands basics of participating in and/or establishing a collaborative project. Describes flexible, caring, and adaptive methods of communication, that embody cultural humility. Describes behavior that conveys caring, honest and genuine interest when interacting with diverse populations. Develops basic language skills (if applicable). |

Communicates with all members of the team in respectful & culturally appropriate manner. Participates in observational experiences with focus on partnership and relationship building. Demonstrates an understanding of the importance of compassion, integrity, respect, sensitivity, and responsiveness, and exhibits these attitudes consistently in common/uncomplicated situations. Demonstrates basic to intermediate language skills (if applicable). |

Participates in and contributes to advancing a long‐term collaborative project. Develops working relationships. Recognizes how own personal beliefs and values affect interactions and manages them appropriately. Demonstrates an understanding of the importance of compassion, integrity, respect, sensitivity, and responsiveness and exhibits these attitudes consistently in complicated situations. Teaches basic concepts of communication and partnering. Demonstrates intermediate to advanced language skills (if applicable). |

Leads teams/projects at site level, participate in national/international collaborative partnership. Advances a long term collaborative project and begins to develop ideas for future projects and/or participates in a leadership position. Develops long‐term relationships. Teaches intermediate concepts in communication and partnering. |

Collaborates with regional, national, and international partners to assess and develop plans to address locally identified priorities in global health and emergency medical care (National guidelines, national training/staffing plans, etc.). Teaches others the importance of compassion, integrity, respect, sensitivity, and responsiveness and how to exhibit these attitudes consistently in complicated situations. Teaches advanced concepts in communication and partnering. |

|

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 6: Ethics Encompasses the application of basic principles of ethics to global health issues and settings. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|

Demonstrates an awareness of local, national, and international codes of ethics relevant to emergency care. Develops an understanding of basic principles of medical ethics (autonomy, beneficence, justice, non‐maleficence). |

Acts in accordance with the basic principles of medical ethics when participating in global health experiences. Demonstrates an ability to resolve common ethical issues and challenges that arise when working within global health experiences, with vulnerable populations, and/or in low‐resource settings. |

Thinks critically about ethical and professional issues that arise in responding to humanitarian emergencies. Understands and synthesizes the fundamental principles of international standards for the protection of humans in a diverse cultural setting. Understands the ethical issues surrounding research in international settings. |

Promotes and advocates for integrity, accountability, and transparency in the field of global emergency medicine. Applies the fundamental principles of international standards for the protection of human subjects in diverse cultural settings. |

Performs research and authors scholarly publications on global health ethics. Guides and mentors students, residents, and fellows in understanding and overcoming ethical challenges that arise during global health experiences. Develops, disseminates and teaches curricula on ethics in global emergency medical care. |

|

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 7: Professional Practice Professional Practice is the ability of the Emergency Medicine physician or trainee to demonstrate integrity, regard and respect for others in all aspects of global health, including but not limited to field experiences. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|

Identifies common barriers to health and health care in resource‐limited settings at the individual, community, and systemic levels. Articulates common challenges relevant to providing and receiving health care in global settings. Discusses and appreciates varying cultural and regional standards for professionalism issues such as attire, scheduling and communication. |

Discusses the challenges of adapting clinical practice or discipline‐specific skills in a resource‐limited setting. Functions efficiently and in congruence with local cultural and professional standards. |

Demonstrates the ability to adapt clinical practice or discipline‐specific skills in a resource‐limited setting. Acknowledges one's limitations in skills, knowledge and abilities. Contributes to or participates in interventions, quality assurance or educational projects. |

Undertakes a leadership role with respect to a global health project (i.e. as running resident rotation in global health). Oversees a project or team and coordinate efforts at the organizational or local level. |

Acts as an ambassador of the discipline, contributing to the development of emergency medical care in the global context. Oversees multiple global health projects or teams. Coordinates professional advocacy, administrative, or practice improvement efforts at the national or international level. |

|

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 8: Health Equity and Social Justice Health equity and social justice is the framework for analyzing strategies to address health disparities across socially, demographically, or geographically defined populations. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|

Develops an awareness of social justice and human rights principles that exist in global health through gaining knowledge of health disparities. Understands the distinction between equity and equality. Introduces the concept of social responsibility. |

Demonstrates a basic understanding of the relationships between health, human rights, and global inequities. Develops an awareness of the healthcare system and barriers to care in the developing world, and the factors that contribute to this. Identifies organizations dedicated to social responsibility/articulate concepts of social responsibility. Participates in observational experiences with a focus on cultural understanding. |

Describes the role of WHO in linking health and human rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. Develops a detailed plan to interact with and engage marginalized and vulnerable populations. Identifies and partners with organizations committed to health equity and social justice. |

Engages marginalized and vulnerable populations in making decisions that affect their health and well‐being. Develops projects in conjunction with stakeholder partners, with the foundation of the work resting on core tenets of promoting health equity and social justice. |

Partners with international stakeholders and policymakers to identify and implement effective programs and policies focused on mitigating health disparities and promoting social justice. | |

| Demonstrates a commitment to social responsibility. | |||||

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 9: Program Management Program management is the ability to design, implement, and evaluate global health programs to maximize contributions to effective policy, enhanced practice, and improved and sustainable health outcomes. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

| Defines the elements of program management: ability to design, implement, and evaluate global health programs to maximize contributions to effective policy, enhanced practice, and improved and sustainable health outcomes. |

Describes features of effective programs and the characteristics that lead to efficacy in policy, practice and health outcomes. Describes some pitfalls of ineffective programs. |

Identifies and describes specific design elements, implementation tools, program components and their applicability to a specific program or system. Describes and demonstrates examples of evaluation tools/methods used in program management. Designs pilot systems with appropriate assistance and mentorship. |

Designs a global health program management intervention. Implements a global health program management intervention. Creates and implements an evaluation tool to measure program outcomes. |

Participates in, contributes to, and/or leads interpretation/synthesis of data for the production of summary documents and policy recommendations. Offers modifications and implements changes as a result of measured outcomes/analysis. Collaborates in the development, implementation and evaluation of multinational policy and program management. Participates in multi‐institutional/national committees or programs for educational advancement of program management. |

|

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 10: Sociocultural and Political Awareness Sociocultural and political awareness is the conceptual basis with which to work effectively within diverse cultural settings and across local, regional, national, and international political landscapes. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|

Demonstrates understanding of general concepts cultural proficiency, aptitude and competency. Identifies key international organizations and their general roles and relationships (UNHCR, UNICEF, WHO, USAID, Ministry of Health, etc.). Defines culture and identifies own cultural characteristics. |

Identifies pertinent sociocultural and political relationships in reference to a specific site/community (demographics, history, current political climate, cultural norms, etc.). Performs self‐assessment of one's own potential biases. Describes differences in own and cross‐cultural settings. Articulates anticipated barriers that may arise while working in new cultural context. Identifies current political situation and individuals and/or groups that contribute to local organizational structure. |

Critically analyzes a program or intervention for potential sociocultural or political conflicts. Adopts tools to mitigate cultural barriers. Recognizes own biases. Identifies larger political organizations/international organizations that shape regional and national structure. |

Teaches basic sociocultural and political awareness concepts and relationships to junior learners. Understands relationship between regional, national and international political structures. Critically analyzes a program or intervention for potential sociocultural or political conflicts. |

Creates or strengthens multidisciplinary partnerships across organizations, including those outside the health sector. Develops curricula to help others understand and work successfully in cross‐cultural landscapes. Participates in direction of local, national, regional or international policy. |

|

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

|

Domain 11: Strategic Analysis Strategic analysis is the ability to use systems thinking to analyze a diverse range of complex and interrelated factors shaping health trends to formulate programs at the local, national, and international levels. | |||||

| Has not achieved Level 1 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|

Identifies how demographic and other major factors can influence patterns of morbidity, mortality, and disability in a defined population. Demonstrates ability to conduct a literature search, and identify morbidity and mortality factors. Identifies key partners and stakeholders and their role. |

Demonstrates the ability to apply a planning framework to a disease issue or situation. | Demonstrates the ability to conduct a community health needs assessment. Steps include determination of an appropriate methodology for assessment, as well as creation and/or validation of survey tools for assessment. |

Conducts a situation analysis across a range of cultural, economic and health contexts. Integrates priority setting, and demonstrate the ability to apply findings to a larger framework. |

Designs and implements context specific health interventions based on situational analysis. Develops appropriate accompanying evaluation tools, and effective means for both piloting and roll‐out of intervention. |

|

| ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ | |||||

| Comments: | |||||

Table 3.

Sample‐specific Suggested Resources for Learning

| Domain 1: Global Burden of Disease | |

|---|---|

| Level 1 |

|

| Level 2 |

|

| Level 3 |

|

| Level 4 |

|

| Level 5 |

|

| Domain 2: Globalization of Health and Health Care | |

| Level 1 |

|

| Level 2 |

|

| Level 3 |

|

| Level 4 |

|

| Level 5 |

|

Table 4.

Assessment Methods

| Level 1 |

|

| Level 2 |

|

| Level 3 |

|

| Level 4 |

|

| Level 5 |

|

Limitations

The Global Health Milestones Tool was developed by a working group of EM practitioners based in the United States. While representing a variety of levels of training and a breadth of experience, and while we did receive feedback from international partners, this is still a significant limitation. We acknowledge this limitation and intend to more actively engage international partners in the pilot phase of the project. Furthermore, the EWG and subsequently the tool that has been developed is specialty specific in EM. This was a deliberate decision made in the context of the Think Tank and acknowledging the significant number of fellowship programs in EM and global health around the world, but nonetheless is a limitation of this work.

Conclusions and next steps

The Global Health Milestones Tool presented here may provide a useful instrument for learners and teachers in emergency medicine. Ideally, this progressive approach to learning and assessment can provide guidance for the most basic exploration of global health experiences in emergency medicine as well as more advanced practitioners. It may serve as a longitudinal assessment tool that can be utilized for learners from medical school, through residency and fellowship and into professional practice.

The next step for the Education Working Group will be to distribute and pilot this tool and assess for both validity and functionality. Any educational tool is only as good as it is usable; thus, we have aimed for our tool to be accessible and to appeal to a broad spectrum of stakeholders including learners and teachers, both domestically and abroad. This tool is designed to be used in conjunction with mentorship and other assessment tools. For example, if a resident will be participating in a clinical global health elective, one strategy could be to use this set of milestones together with specific relevant emergency medicine milestones. Then, the learner, mentor, and in‐country supervisor would each complete some piece of the combined milestones, providing opportunity for both external assessment and self‐assessment. Together this may provide a more comprehensive, holistic understanding of the learners' knowledge and skills in both clinical areas and global health.

While this tool has been designed with learners in EM in mind, most of the elements are not specialty specific. The tool could be easily adaptable to learners in primary and acute care settings, especially because EM and acute care are integrally related and often overlapping on the continuum of care. It may be minimally modified for application to another specialty or application in any resource‐limited setting.

The Global Health Milestones Tool provides a framework for learners in emergency medicine to attain the knowledge necessary for global health work and mentors to work toward more effective assessment. Future research will elucidate how it can be optimally put into practice.

We thank the Society for Emergency Medicine and its Global Emergency Medicine Academy for hosting the Global Emergency Medicine Think Tank. We also acknowledge the support of all the members of the Global Emergency Medicine Think Tank Education Working Group listed below:

Supporting information

Data Supplement S1. Remainder of specific suggested resources for learning.

An electronic version of the milestones outlined in this paper, in addition to other usable tools, can be obtained from the authors. Please contact Katherine Douglass, MD, MPH, FACEP at kdouglass@mfa.gwu.edu.

Working Group Members

John Acerra, MD, MPH, Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine

Christina Bloem, MD, MPH, State University of New York, Downstate

Jay Brenner, MD, SUNY‐Upstate Medical University

Elizabeth DeVos, MD, MPH, University of Florida, Jacksonville

Katherine Douglass, MD, MPH, The George Washington University

Brad Dreifuss, MD, University of Arizona

Alison S Hayward, MD, MPH, Yale University School of Medicine

Sue Lin Hilbert, MD, MPH, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine

Gabrielle A. Jacquet, MD, MPH, Boston University School of Medicine

Janet Lin, MD, MPH, University of Illinois, Chicago

Andrew Muck, MD, University of Texas, San Antonio

Sigrid Nasser, MD, The George Washington University

Rockefeller Oteng, MD, University of Michigan

Natasha N. Powell, MD, MPH, The George Washington University

Megan M. Rybarczyk, MD, Boston Medical Center

Jessica Schmidt, MD, MPH, University of Wisconsin

Jim Svenson, MD, MS, University of Wisconsin

Janis P. Tupesis MD, University of Wisconsin

Kyle Yoder, MD, The George Washington University

AEM Education and Training 2017;1:269–279.

Financial support for the organization of the Global Emergency Medicine Think Tank was provided by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. No additional financial support was provided for the development of this article.

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1. Drain P, Primack A, Hunt D, Fawzi W, Holmes K, Gardner P. Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med 2007;82:226–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Drain P, Holmes K, Skeff K, Hall T, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs and opportunities. Acad Med 2009;84:320–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. King RA, Liu KY, Talley BE, Ginde AA. Availability and potential impact of international rotations in emergency medicine residency programs. J Emerg Med 2013;44:499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khan O, Guerrant R, Sanders J, et al. Global health education in U.S. medical schools. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Battat R, Seidman G, Chadi N, et al. Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jogerst K, Callender B, Adams V, et al. Identifying interprofessional global health competencies for 21st‐century health professionals. Ann Glob Health 2015;81:240–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Redwood‐Campbell L, Pakes B, Rouleau K, et al. Developing a curriculum framework for global health in family medicine: emerging principles, competencies, and educational approaches. BMC Med Educ 2011;11:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tupesis JP, Jacquet GA, Hilbert S, et al. The role of graduate medical education in global health: proceedings from the 2013 Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:1216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martin IB, Devos E, Jordan J, et al. Global health and emergency care: an undergraduate medical education consensus‐based research agenda. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:1224–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tupesis JP, Babcock C, Char D, Alagappan K, Hexom B, Kapur GB. Optimizing global health experiences in emergency medicine residency programs: a consensus statement from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors 2011 Academic Assembly global health specialty track. Int J Emerg Med 2012;5:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beeson MS, Carter WA, Christopher TA, et al. Emergency medicine milestones. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5(1 Suppl 1):5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swing S. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach 2007;29:648–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamstra SJ, Edgar L, Yamazaki K, Holmboe E; Milestones Team . Milestones Annual Report 2016. ACGME. 2016. Oct. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/MilestonesAnnualReport2016.pdf Accessed Feb 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dreyfus S. The five‐stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bull Sci Technol Soc 2004;24:177. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eichbaum Q. The problem with competencies in global health education. Acad Med 2015;90:414–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Supplement S1. Remainder of specific suggested resources for learning.

An electronic version of the milestones outlined in this paper, in addition to other usable tools, can be obtained from the authors. Please contact Katherine Douglass, MD, MPH, FACEP at kdouglass@mfa.gwu.edu.