Abstract

Objectives

To determine and explore the influences on care preferences of older people with advanced illness and integrate our results into a model to guide practice and research.

Design

Systematic review using Medline, Embase, PsychINFO, Web of Science, and OpenGrey databases from inception to February 2017 and reference and citation list searching. Included articles investigated influences on care preference using qualitative or quantitative methodology. Thematic synthesis of qualitative articles and narrative synthesis of quantitative articles were undertaken.

Setting

Hospital and community care settings.

Participants

Older adults with advanced illness, including people with specific illnesses and markers of advanced disease, populations identified as in the last year of life, or individuals receiving palliative care (N = 15,164).

Measurements

The QualSys criteria were used to assess study quality.

Results

Of 12,142 search results, 57 articles were included. Family and care context, illness, and individual factors interact to influence care preferences. Support from and burden on family and loved ones were prominent influences on care preferences. Mechanisms by which preferences are influenced include the process of trading‐off between competing priorities, making choices based on expected outcome, level of engagement, and individual ability to form and express preferences.

Conclusion

Family is particularly important as an influence on care preferences, which are influenced by complex interaction of family, individual, and illness factors. To support preferences, clinicians should consider older people with illnesses and their families together as a unit of care.

Keywords: systematic review, patient preference, terminally ill, terminal care, palliative care

Worldwide demographic changes mean that more people are living with and dying from chronic illness and multimorbidity, and this number is expected to rise.1, 2 The prevalence of chronic illness rises with age,3 so delivery of high‐quality care in this growing population group is a priority.4, 5

Care of older people with chronic illness is often complex,6, 7 and to deliver person‐centered care in this population, a clear understanding of the person's preferences for care is needed.8 Person‐centered care seeks to provide what is necessary to meet individuals’ physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs by focusing on what is important to them,5 and care preferences can be defined as what people want from their care.9 They can be broadly classified as preferences for the context in which care is delivered; preferences for care relationships; preferences for involvement in care; and preferences for care outcomes, such as comfort versus extending life or place of death.10, 11 Observational studies have determined the content of care preferences in this population.12, 13

Nevertheless, people do not simply have preferences, so we need to know more than the content of preferences to deliver responsive care. Preferences may become clear only as they are elicited or may vary in importance at different times. Equally, changes in contextual factors or experience may influence preferences.14, 15, 16 Influences on care preferences have been investigated in qualitative and quantitative studies,17, 18, 19 particularly factors associated with preference for home care or home death.20, 21 One model lists illness‐related factors, individual factors, and environmental factors associated with place of death.22 Qualitative studies have highlighted the importance of family support, personal experience and values as influences on preferences,23, 24 but this evidence is mainly from small observational studies. This body of evidence has never been synthesized.

To deliver care in line with personal preferences, it is important to understand how they are influenced at a broader level. Therefore, this review aimed to synthesize evidence regarding the influences on preferences for care of older people with advanced illness, producing a model of the influences on care preferences in this population.

Methods

This systematic review followed the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses guidelines25 and was based on a pre‐agreed protocol.

Search strategy and selection of articles

We searched online databases (Medline (Ovid), Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science), grey literature repositories (Open Grey), and theses (EThos database) from inception to February 2017. The search strategy used Medical Subject Headings and synonyms related to “preferences,” “advanced illness,” and “older people” and was adapted from search strategies used in previous systematic reviews.10, 13, 26, 27 See Appendix S1 for the full search strategy. No limits were placed on language or date. We also hand‐searched reference and citation lists of included articles. The search was updated in December 2017. See Table 1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria, and article selection process.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

Articles were screened by title and abstract, and those unrelated to influences on care preferences were discarded. Full texts of remaining articles were assessed for inclusion by one researcher (SE), with 10% cross‐checking by another researcher (AB). Disagreements were resolved by discussion within the multidisciplinary research team. When full text was unavailable, an attempt was made to contact the original authors. Attempts were also made to find follow‐up articles from relevant conference abstracts.

Quality assessment

Because this review includes studies of varied design, we used the validated QualSys guidelines, designed for this purpose, to assess the quality of included articles.30 QualSys incorporates separate checklists of criteria for qualitative and quantitative studies. Each criterion is rated on a scale from 0 to 2, and a total score is calculated. The research team agreed that a score of 75% or greater was required for high quality and 60% or greater for medium quality. No articles were excluded on quality, although we used QualSys scores, alongside quantity and agreement of evidence, to appraise the strength of evidence supporting the quantitative synthesis, based on existing criteria designed for this purpose.22, 31

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted from included articles using a bespoke pro forma that the research team agreed on in advance. Basic data from each study (e.g., authors, country, sample size) were extracted. For quantitative articles, findings regarding influences on care preferences were extracted. For qualitative studies, the entire Results or Findings section was extracted for thematic synthesis.

The “three synthesis” approach proposed for reviews of mixed studies was used in the analysis.32 Thus two initial syntheses were undertaken, one each for quantitative and qualitative studies, followed by a third integrative synthesis.33, 34, 35, 36

Thematic synthesis, supported by NVIVO Software version 10 (QSR International (UK) Ltd.), was used for qualitative synthesis. This involved reading, re‐reading, and then coding all relevant text within the Results sections of included articles. We first coded inductively, allowing for themes to emerge from the data.35 Deductive coding, based on existing models, was then applied to ensure relevance to previous work.22, 23, 35 In particular, we used the Gomes model, which identifies illness, individual, and environmental influences on place of death,22 and the experience, health condition, and family components of the Hattori model.23 Inductive and deductive coding were combined to produce a final model that fit with the original data. Using the entire Results section for analysis meant that raw data and author interpretations were synthesized, allowing us to build on existing work.35, 37

For the quantitative synthesis, the variation in outcomes across included articles precluded meaningful meta‐analysis. Therefore a descriptive synthesis of factors associated with care preferences was undertaken. Factors were grouped by preference category, and the direction of the effect was recorded. Associations were linked to the strength of evidence supporting them.

In the integration stage, findings from the quantitative synthesis were mapped onto the qualitative model to produce an integrated model of the influences on care preferences, using existing models as a starting point.22, 23 Triangulation of qualitative and quantitative data was used to identify areas where evidence from different methodology concurred and areas where there was disagreement.

Results

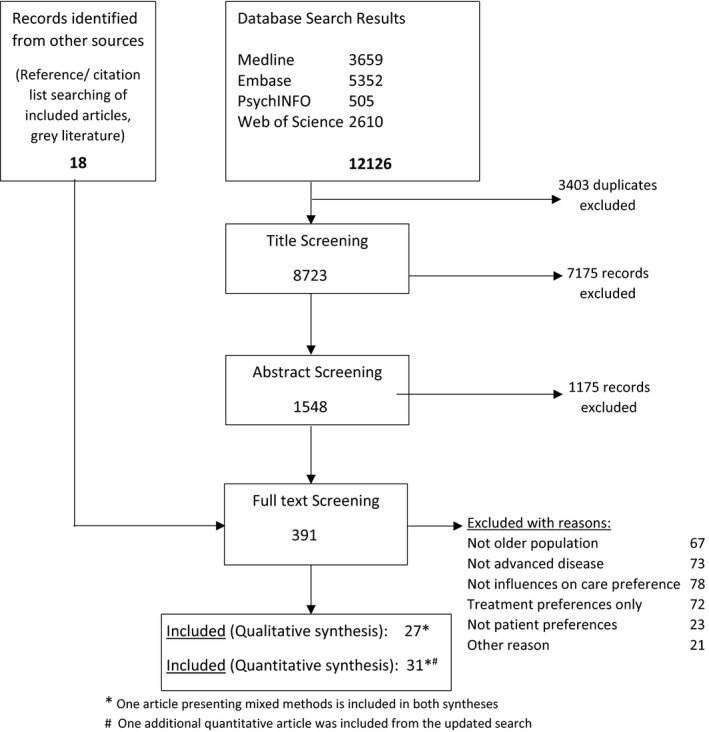

The search retrieved 8,723 records once duplicates were removed; 391 full‐text articles were reviewed, and of these, 26 qualitative papers, 30 quantitative papers, and 1 mixed‐methods analysis were included (Figure 1). Included papers were published between 1995 and 2017. In total 14,474, unique participants were included in the quantitative papers and 857 in the qualitative papers. Twenty‐five (44%) studies were conducted in North America, 19 (33%) in Europe, 8 (14%) in Asia, and 3 (5%) in Australasia, and 2 (4%) collected data internationally.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses chart.

The 27 qualitative papers (Table 2) investigated influences on preferences for care context (place of care), care involvement (communication and decision‐making), and care outcomes (quality of life, place of death). Thirteen papers were of high quality, 13 of medium quality, and 1 of low quality. All studies used interviews, ranging from structured interviews to unstructured in‐depth interviews. The 30 quantitative papers (see Appendix S3 for details) varied in sample size from 38 to 2,452, and methodology ranged from in‐person questionnaires to national postal surveys. Sixteen were high quality, 11 medium quality, and 3 low quality.

Table 2.

Details of Included Qualitative Studies

| Article information | Design | Sample Size, n | Care preference domain11 | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdul‐Razzak, 2014, Canada17 | Semistructured interviews | 16 | Involvement, relationships | High |

| Bradley, 1999, United States24 | Open‐ended interviews | 10 | Outcomes | High |

| Broom, 2013, Australia38 | In‐depth interviews | 20 | Relationships, outcomes | Medium |

| Caldwell, 2007, Canada39 | In‐depth interviews | 20 | Involvement | High |

| Fleming, 2016, United Kingdom40 | Topic‐guided interviews | 42 | Involvement, relationships, outcomes | Medium |

| Fried, 1999, United States41 | Interviews in mixed‐methods study | 29 | Outcomes | Low |

| Fried, 1998, United States42 | Interviews in mixed‐methods study | 29 | Context, outcomes | High |

| Gardner, 2010, United States43 | Semistructured interviews | 20 | Involvement, outcomes, relationships | High |

| Goodman, 2013, United Kingdom44 | Guided conversations | 18 | Involvement, relationships, outcomes, context | Medium |

| Hanratty, 2013, United Kingdom45 | In‐depth interviews | 32 | Context, relationships | High |

| Hattori, 2005, Japan23 | Interviews | 30 | Relationships, outcomes, involvement | Medium |

| Kelner, 1995, Canada46 | Interviews | 38 | Involvement | Medium |

| Klindtworth, 2015, Germany47 | Serial interviews | 25 | Involvement, outcomes | High |

| Kuluski, 2013, Canada48 | Qualitative interviews | 27 | Relationships, outcomes | High |

| Laakkonen, 2004, Finland49 | In‐depth interviews | 11 | Relationships, involvement | High |

| Lambert, 2005, Canada50 | Semistructured interviews | 9 | Involvement | Medium |

| Lowey, 2013, United States51 | Serial semistructured interviews | 20 | Outcomes | High |

| Mathie, 2012, United Kingdom52 | Serial qualitative interviews | 63 | Involvement, outcomes | Medium |

| McCall, 2005, United Kingdom53 | Semistructured interviews | 13 | Context, outcomes | Medium |

| Naik, 2016, United States54 | Serial structured interviews | 146 | Outcomes | High |

| Piers, 2013, Belgium55 | Semistructured interviews | 38 | Involvement | Medium |

| Romo, 2016, United States56 | Semistructured interviews | 20 | Involvement | High |

| Selman, 2007, United Kingdom57 | Semistructured interviews | 20 | Outcomes, relationships, involvement | Medium |

| Tang, 2003, United States58 | Semistructured interviews | 180 | Outcomes | Medium |

| Thomas, 2004, United Kingdom59 | In‐depth interviews | 41 | Outcomes | Medium |

| Vig, 2002, United States60 | Semistructured interviews | 16 | Outcomes, relationships | Medium |

| Vig, 2003, United States61 | In‐depth semistructured interviews | 26 | Outcomes, relationships, involvement | High |

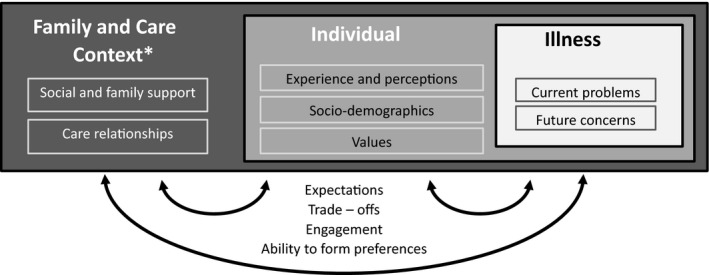

Based on qualitative, quantitative, and integration syntheses, we produced a model of the influences on preferences for care, which extends the Gomes model of influences on place of death.22 Factors influencing care preferences relating to family and care context, the individual, and the illness were identified and explored. We also identified mechanisms by which preferences are influenced (Figure 2). The synthesis indicates that it is the norm in this population for preferences to be incompletely expressed, and a clear decision‐making process regarding preferences is rare. Instead, preferences emerge from a complex interaction of the areas and mechanisms identified in this model, as described below.

Figure 2.

Model of influences on care preferences (extension of Gomes model22). See Appendix S5 for full coding frame. *Includes the ‘environment’ component of the Gomes model.

Three areas describe the influences on care preferences in this population: family and care context, the individual, and the illness. How these are derived from the included qualitative papers and aligned to the model is outlined below.

Family and care context

The strongest influences on preferences came from concerns of and about family, and the wider care environment. We found that trusting care relationships influence preferences for communication and that the level of support available from health professionals and family is an important determinant of preferences for care. The wish to avoid being a burden often influenced preferences, and the views of and concerns about family were of paramount importance:

Just to keep my daughter as calm as possible—that's the main thing. I don't want to upset her any more than I have to. What can you do? Your parents die, that's going to happen, so … there is nothing to be done about it, but I want to, want her to be as calm as possible. (82‐year‐old female) Gardner et al. 43

Frequently, concerns about family were more prominent than individuals’ own concerns about care preferences.

Although patients’ wishes may not be their preference, such was their concern about their carer and not wanting to become a burden; they were not prepared to consider any other option for place of end‐of‐life care. McCall et al.53

The Individual

Characteristics of individuals such as age influenced preferences in some cases. Past experience of care, especially caring for others at the end of life, influenced preferences for one's own care, whether relevant to one's situation or not.

One of the most universal and influential events in the lives of the residents was the death of a family member or close friend. This influence was attributed to grief, and by facts about end‐of‐life decisions and death learned from the experience. In many cases, the situation of the loved one was not comparable with the resident's current situation. Nevertheless, many residents applied the experience of the deceased as if it were identical to their own situation. The opinions generated by these experiences were so strong that they were not overridden by factual information about the residents’ own health. Lambert et al.50

Perceptions of care, often based on experience, were seen to shape preferences, sometimes very strongly.

Beliefs about what medical care was possible … shaped preferences so fundamentally that a number of respondents could not form a preference distinct from these beliefs. Fried et al. (1998).42

Personal values, which are often long‐held views, were another strong influence on preferences, for example a value of maintaining comfort may result in prioritization of quality over quantity of life.

The desire to “die easily, without suffering” was the most prevalent underlying wish, and one which never changed. Hattori et al.23

A long‐held desire to maintain independence may influence preference for place of care.

I want to be self‐sufficient. I don't want to be sick. Until I'm overwhelmed, I want to be able to deal with it [my illness] on my terms (CA1030).54

The Illness

The illness context strongly influenced preferences, particularly for those who were aware of their disease status and accepted their situation.

But you know it has to end sometime when you are 80 and are also terminally ill [cancer]. Then you know that you have to accept it. [interview 25] Piers et al.55

Concerns about future changes in health were another area influencing care preferences.

A number of participants wished to be placed in a nursing facility when the time came, assuming their physical functions would deteriorate and they would require nursing care in the future. Hattori et al.23

Mechanisms

In the qualitative synthesis, we identified mechanisms by which these areas interact, namely, expectations, trade‐offs, engagement, and ability to form and express preferences.

Expectations

Personal experience, perceptions, illness context, and level of knowledge combined to produce expectations about the future, which guided care preferences, especially with regard to place of care.

Preferences for site of care depended on the anticipated outcome of the illness episode. Fried et al. 1998.42

Maintaining and maximising personal dignity given the prospect of loss of control over bodily functions, of extreme pain, or of ‘going mad,’ was bound up with a preference to place their final care in the hands of professionals in a hospice setting. Thomas et al.59

Trade‐Offs

Personal values, illness context, and the wider care environment may be traded off in formulation of preferences. Presence and support of family exerted a strong influence on preferences, and the views of loved ones may supersede personal views and perceptions.

I would prefer to be at home. Um, but then again, by the same token, if hubby doesn't think he can cope, which, it may come to that point, where he can't cope, with the whole physical thing, the mental thing of me being at home, then I will willingly come in [again]. (Female, married, 51–60). Broom et al.38

Engagement

Preferences were not always actively expressed, and disengagement, or “living in the moment,” was common. Leaving decisions to chance or delegating to others may result.

I never thought about that. I think it should be left to the doctor. Fleming et al.40

Conversely, some seek to keep control and maintain independence and may express stronger preferences. Engagement also depends on temporal focus, acceptance of the illness context and personal self‐efficacy.

I am my own boss, am I not? My children don't control me. I decide what I want. Whether they like it or not, yes it's my decision. It's my body. That's my opinion and no one can help me with that, no. [interview 30]. Piers et al.55

Ability to form and express preferences

Illness, cognitive impairment, or disengagement commonly resulted in low self‐efficacy, such that preferences were not formed or expressed. Expectations, trade‐offs, and engagement were less relevant to this group, who were unable to form preferences using these mechanisms.

The data suggested that perceptions of self‐efficacy may influence not only the likelihood of setting explicit goals but also the nature of goals themselves. Low self‐efficacy resulted in either the setting of no or less challenging goals. Bradley et al.24

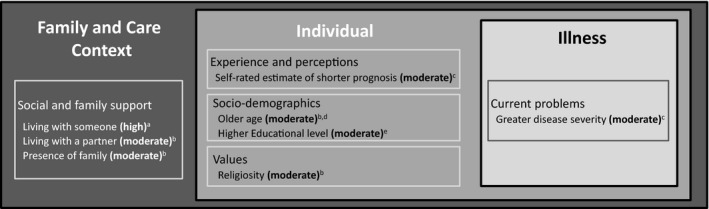

The quantitative synthesis also identified factors associated with care preferences, which we used to confirm and extend this model. In particular, sociodemographic variables (including age, sex, religiosity, educational level, presence or absence of social support) were associated with preferences for care. The associations supported by moderate or high strength evidence are presented in Figure 3. For a full list of associations, see Appendix S4. In particular, education and social class were associated with preferences for greater involvement in communication, whereas a higher level of social and family support was associated with preferences for home care and home death.

Figure 3.

Associations with care preferences from quantitative synthesis—high‐ and moderate‐strength evidence. aAssociated with preference for home death. bAssociated with preference for home care. cAssociated with preference for comfort versus life prolonging care. dAssociated with preference for less information about end of life. eAssociated with preference for greater involvement in decision‐making. Strength of evidence is indicated in bold in brackets. High‐strength evidence requires at least 3 high‐quality papers with >70% agreement in findings; moderate‐strength evidence requires at least 2 papers of medium or high quality with >50% agreement in findings.

Triangulation between qualitative and quantitative syntheses provides support for this model of influences on care preference. Variables related to family (presence of family, trust in family, living with a partner, marital status) were associated with preference for home death, with strong evidence, in line with the extensive discussion of the influence of family in the qualitative data. Illness factors including diagnosis, comorbidity level, and disease severity were associated with care preferences, in line with qualitative findings, although the specific associations were inconsistent, resulting in weaker evidence.

Discussion

This systematic review and thematic synthesis brings together, for the first time, qualitative and quantitative evidence regarding influences on care preferences in older people with advanced illness. Family and care context, particularly support from family, are dominant influences on care preferences in this population. These factors interact with individual—sociodemographic characteristics, personal experience, and values—and illness‐related factors to influence care preferences. We identify four mechanisms affecting how these areas interact, conscious or unconscious trade‐offs, consideration of what is expected to occur, engagement with preferences, and ability to form or express preferences.

The great importance of family support is evident in qualitative and quantitative data. “Living with someone” was the only factor associated with a care preference with high strength evidence. In the qualitative synthesis, concerns about family and concerns of family were strong enough to cause many people to change their preferences. The nuances of family relationships are therefore important in determining preferences. This supports the concept in the palliative care literature that the unit of care should be the person and his or her family, not the person alone.62 Previous work has demonstrated the importance of family in decision‐making63, 64 but has not demonstrated the influence of family support on a wide range of preferences.

Our findings highlight the overarching importance of family and perceived family support when discussing preferences in practice, and it is clear that family should be part of these conversations. Because concerns about family may result in people expressing preferences different from their underlying wishes, clinicians cannot necessarily take stated preferences at face value. Instead, they should consider how they can best provide support to patients and their families to allow patients to achieve their preferences, particularly when there is conflict in views between individuals and those close to them.

We also identify potential areas clinicians could focus on to support patient preferences. It may be impossible to change illness or individual factors, but it is potentially possible to make positive changes to care and to support family involvement.65 An individual whose preference for place of care is home but is concerned about the effect on his or her family may trade off and change his or her preference to institutional care. Discussion about how the family may be better supported might allow the individual to stay in their preferred place of care.

The mechanisms we identify in this synthesis extend existing theory. Economic theories of preference, such as expectancy value theory, consider preferences as a process of trading off expected outcome and the value one would place on that outcome.66 Expectations are highlighted as a mechanism for “response shift,”16 and cognitive theories of preference also consider the process of trading off to be important,67 although these theories do not consider the importance of individual engagement and the ability to form and express preferences, which came across strongly in our synthesis. Older people, especially those with cognitive impairment, may choose to cede control or may not wish to consider preferences overtly. Others may be cognitively unable to express preferences.44 In this situation, the importance of the care context and family support grows.8 Our model therefore highlights the importance of broader, nonrational processes influencing preferences,9, 68 as well as the trade‐offs and expectation‐based mechanisms proposed in economic and cognitive models.

This review has found considerable research into care preferences in this population, but many studies are small and not of high quality, with inconsistent reporting of nonsignificant findings. Some areas that might be expected to influence preferences—ethnicity, culture, religion—were not prominent in this synthesis, although there was some evidence that religiosity is associated with preference for place of care. This probably represents absence of evidence, rather than evidence that these areas do not influence preferences, and further study is needed.

Most included quantitative studies are cross‐sectional, which limits the inferences that can be drawn from associations. The influence of time on preferences is evident in some of the qualitative data, but it is unclear how the various influences on preference interact to affect the stability of preferences over time. Studies that collect data serially show that a large minority of participants change their preferences,69, 70 so it is important to know how changes in illness, individual, family, and environmental factors over time may affect preference stability. Further prospective research is needed to describe and explore influences on the stability of care preferences in this population.

A strength of this review is the systematic methodology, resulting in a robust model based on international qualitative and quantitative data. The three synthesis approach allowed triangulation between methodologies, which increased the robustness of our model. Inclusion of articles investigating a range of care preferences increased the scope of the model and its applicability. Although the evidence in this area is spread across fields and is challenging to identify, our use of a systematic, evidence‐based search strategy without limitations on language or publication date means that we are confident we have identified the relevant evidence, although it is possible that some studies were missed. We found that quantitative studies inconsistently reported nonsignificant findings. Our synthesis therefore focused primarily on significant findings, which may have introduced a bias against negative findings, although including the nonsignificant findings that were reported did not affect our final model. Focusing on a more specific set of care preferences might have resulted in a more precise, albeit less broadly applicable synthesis. Additionally, thematic analysis of published articles inevitably limits the conclusions that can be drawn from the data because there is no access to the original data set.

In conclusion, this systematic review shows the importance of family and care context, particularly family support, as influences on care preferences. These factors combine with individual and illness‐related factors to influence preferences through mechanisms of trade‐offs, expectations, engagement, and the ability to form and express preferences. Clinicians must take these factors and mechanisms into account when considering preferences. Influences on the stability of care preferences are unclear, and further investigation with prospective longitudinal research is needed.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Full search strategy for each database.

Appendix S2. Definitions.

Appendix S3. Details of quantitative papers.

Appendix S4. Full quantitative synthesis.

Appendix S5. Qualitative coding framework.

Appendix S6. Strength of evidence assessment details.

Appendix S7. Additional references.

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Cottrell (Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care Policy & Rehabilitation, Kings College London, London, United Kingdom) for assistance with qualitative data analysis and all collaborators and advisors, including service users, and members of the International Access, Rights and Empowerment II study group: Lara Klass, Bridget Johnston, Peter May, Regina McQuillan, Karen Ryan, Diane Meier, Sean Morrison, Charles Normand, Deokhee Yi, Melissa Aldridge, Natalie Johnson.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions: Designing and winning funding for study and fellowship, overall leadership of programme: IJH. Systematic review concept and development, including writing of protocol: SE, FM, IJH. Undertaking search, screening of results, data extraction and quality assessment: SE, AB, NL. Analysis: SE, NL, AB. Drafting of paper and approval of final draft: SE, AB, NL, FM, IJH.

Sponsor's Role: This work was independent research funded by Cicely Saunders International and the Atlantic Philanthropies (Grant 24610). The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of this paper. This research was supported by the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care, South London, which is part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and is a partnership between King's Health Partners, St. George's University London, and St George's Healthcare National Health Service (NHS) Trust. IJH is an Emeritus NIHR Senior Investigator. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or the Department of Health.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation . Projections of mortality and causes of death, 2015 and 2030 [on‐line]. Available at http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/projections/en/. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- 2. Etkind SN, Bone AE, Lovell N, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med 2017;15:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross‐sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eaton S, Roberts S, Turner B. Delivering person centred care in long term conditions. BMJ 2015;350:h181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The Health Foundation . Person‐Centred Care Made Simple. London, UK: The Health Foundation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coventry PA, Small N, Panagioti M, Adeyemi I, Bee P. Living with complexity; marshalling resources: a systematic review and qualitative meta‐synthesis of lived experience of mental and physical multimorbidity. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Onder G, Palmer K, Navickas R et al. Time to face the challenge of multimorbidity. A European perspective from the joint action on chronic diseases and promoting healthy ageing across the life cycle (JA‐CHRODIS). Eur J Intern Med 2015;26:157–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanson LC, Winzelberg G. Research priorities for geriatric palliative care: Goals, values, and preferences. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1175–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Street RL, Elwyn G, Epstein RM. Patient preferences and healthcare outcomes: An ecological perspective. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaldjian LC, Curtis AE, Shinkunas LA, Cannon KT. Review article: Goals of care toward the end of life: A structured literature review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2009;25:501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient‐centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000;284:2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sandsdalen T, Hov R, Høye S, Rystedt I, Wilde‐Larsson B. Patients’ preferences in palliative care: A systematic mixed studies review. Palliat Med 2015;29:399–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Winter L, Parker B. Current health and preferences for life‐prolonging treatments: An application of prospect theory to end‐of‐life decision making. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:1695–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979;47:263–291. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwartz CE, Sprangers MA. Adaptation to Changing Health: Response Shift in Quality‐of‐Life Research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abdul‐Razzak A, You J, Sherifali D, Simon J, Brazil K. ‘Conditional candour’ and ‘knowing me’: An interpretive description study on patient preferences for physician behaviours during end‐of‐life communication. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chu LW, Luk JKH, Hui E et al. Advance directive and end‐of‐life care preferences among Chinese nursing home residents in Hong Kong. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011;12:143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tang ST, Liu TW, Chow JM et al. Associations between accurate prognostic understanding and end‐of‐life care preferences and its correlates among Taiwanese terminally ill cancer patients surveyed in 2011–2012. Psychooncology 2014;23:780–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iecovich E, Carmel S, Bachner YG. Where they want to die: Correlates of elderly persons’ preferences for death site. Soc Work Public Health 2009;24:527–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brogaard T, Neergaard MA, Sokolowski I, Olesen F, Jensen AB. Congruence between preferred and actual place of care and death among Danish cancer patients. Palliat Med 2013;27:155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: Systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:515–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hattori A, Masuda Y, Fetters MD et al. A qualitative exploration of elderly patients’ preferences for end‐of‐life care. Japan Med Assoc J 2005;48:388–397. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bradley EH, Bogardus ST Jr, Tinetti ME, Inouye SK. Goal‐setting in clinical medicine. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sladek R, Tieman J, Fazekas BS, Abernethy AP, Currow DC. Development of a subject search filter to find information relevant to palliative care in the general medical literature. J Med Libr Assoc 2006;94:394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sharp T, Moran E, Kuhn I, Barclay S. Do the elderly have a voice? Advance care planning discussions with frail and older individuals: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e657–e668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ditto PH, Jacobson JA, Smucker WD, Danks JH, Fagerlin A. Context changes choices: A prospective study of the effects of hospitalization on life‐sustaining treatment preferences. Med Decis Making 2006;26:313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Auriemma CL, Nguyen CA, Bronheim R et al. Stability of end‐of‐life preferences: A systematic review of the evidence. JAMA Inter Med 2014;174:1085–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. Edmonton, Canada: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoogendoorn WE, van Poppel MN, Bongers PM, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Systematic review of psychosocial factors at work and private life as risk factors for back pain. Spine 2000;25:2114–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. California, USA: Sage, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harden A, Garcia J, Oliver S et al. Applying systematic review methods to studies of people's views: An example from public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:794–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oliver S, Harden A, Rees R et al. An emerging framework for including different types of evidence in systematic reviews for public policy. Evaluation 2005;11:428–446. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harden A, Thomas J. Mixed methods and systematic reviews: Examples and emerging issues In: Teddlie C, Tashakkori A, eds. Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. California, USA: Sage, 2010, pp. 749–774. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005;52:546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Broom A, Kirby E. The end of life and the family: Hospice patients’ views on dying as relational. Sociol Health Illn 2013;35:499–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caldwell PH, Arthur HM, Demers C. Preferences of patients with heart failure for prognosis communication. Can J Cardiol 2007;23:791–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fleming J, Farquhar M, Brayne C et al. Death and the oldest old: Attitudes and preferences for end‐of‐life care—qualitative research within a population‐based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2016;11:e0150686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fried TR, Van Doorn C, O'Leary JR, Tinetti ME, Drickamer MA. Older persons’ preferences for site of terminal care. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fried TR, van Doorn C, Tinetti ME, Drickamer MA. Older persons’ preferences for site of treatment in acute illness. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:522–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gardner D, Kramer B. End‐of‐life concerns and care preferences: Congruence among terminally ill elders and their family caregivers. Omega (Westport) 2010;60:273–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goodman C, Amador S, Elmore N, Machen I, Mathie E. Preferences and priorities for ongoing and end‐of‐life care: A qualitative study of older people with dementia resident in care homes. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:1639–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hanratty B, Addington‐Hall J, Arthur A et al. What is different about living alone with cancer in older age? A qualitative study of experiences and preferences for care. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kelner M. Activists and delegators: Elderly patients’ preferences about control at the end of life. Soc Sci Med 1995;41:537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Klindtworth K, Oster P, Hager K, Krause O, Bleidorn J, Schneider N. Living with and dying from advanced heart failure: Understanding the needs of older patients at the end of life. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kuluski K, Gill A, Naganathan G, Upshur R, Jaakkimainen RL, Wodchis WP. A qualitative descriptive study on the alignment of care goals between older persons with multi‐morbidities, their family physicians and informal caregivers. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Laakkonen ML, Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE. Terminally ill elderly patient's experiences, attitudes, and needs: A qualitative study. Omega (Westport) 2004;49:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lambert HC, McColl MA, Gilbert J, Wong J, Murray G, Shortt SED. Factors affecting long‐term‐care residents’ decision‐making processes as they formulate advance directives. Gerontologist 2005;45:626–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lowey SE, Norton SA, Quinn JR, Quill TE. Living with advanced heart failure or COPD: Experiences and goals of individuals nearing the end of life. Res Nurs Health 2013;36:349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mathie E, Goodman C, Crang C et al. An uncertain future: The unchanging views of care home residents about living and dying. Palliat Med 2012;26:734–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McCall K, Rice AM. What influences decisions around the place of care for terminally ill cancer patients? Int J Palliat Nurs 2005;11:541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Naik AD, Martin LA, Moye J, Karel MJ. Health values and treatment goals of older, multimorbid adults facing life‐threatening illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Piers RD, van Eechoud IJ, Van Camp S et al. Advance care planning in terminally ill and frail older persons. Patient Educ Couns 2013;90:323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Romo RD, Allison TA, Smith AK, Wallhagen MI. Sense of control in end‐of‐life decision‐making. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:e70–e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T et al. Improving end‐of‐life care for patients with chronic heart failure: “Let's hope it'll get better, when I know in my heart of hearts it won't”. Heart 2007;93:963–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tang ST. When death is imminent: Where terminally ill patients with cancer prefer to die and why. Cancer Nurs 2003;26:245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thomas C, Morris SM, Clark D. Place of death: Preferences among cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:2431–2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vig EK, Davenport NA, Pearlman RA. Good deaths, bad deaths, and preferences for the end of life: A qualitative study of geriatric outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1541–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vig EK, Pearlman RA. Quality of life while dying: A qualitative study of terminally ill older men. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1595–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kovacs PJ, Bellin MH, Fauri DP. Family‐centered care. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2006;2:13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kirk P, Kirk I, Kristjanson LJ. What do patients receiving palliative care for cancer and their families want to be told? A Canadian and Australian qualitative study. BMJ 2004;328:1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. You JJ, Dodek P, Lamontagne F et al. What really matters in end‐of‐life discussions? Perspectives of patients in hospital with serious illness and their families. Can Med Assoc J 2014;186:E679–E687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sarmento VP, Gysels M, Higginson IJ, Gomes B. Home palliative care works: But how? A meta‐ethnography of the experiences of patients and family caregivers. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:390–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Atkinson JW. An Introduction to Motivation. Oxford, England: Van Nostrand, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bower P, King M, Nazareth I, Lampe F, Sibbald B. Patient preferences in randomised controlled trials: Conceptual framework and implications for research. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:685–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Peters E, Lipkus I, Diefenbach MA. The functions of affect in health communications and in the construction of health preferences. J Commun 2006;56(Suppl):S140–S162. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pardon K, Deschepper R, Vander Stichele R et al. Changing preferences for information and participation in the last phase of life: A longitudinal study among newly diagnosed advanced lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2473–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Schols JM, Wouters EF. Dynamic preferences for site of death among patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure, or chronic renal failure. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:826–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Full search strategy for each database.

Appendix S2. Definitions.

Appendix S3. Details of quantitative papers.

Appendix S4. Full quantitative synthesis.

Appendix S5. Qualitative coding framework.

Appendix S6. Strength of evidence assessment details.

Appendix S7. Additional references.