Abstract

Background

Ultrasound guidance has become an integral component to procedural and diagnostic practice for the emergency physician. Whereas landmark‐guided methods were used for peripheral nerve blocks in the past, the use of ultrasound has made regional anesthesia procedures faster, more successful, and feasible as a pain management modality in the emergency department. Not only the utilization, but also the teaching of ultrasound has become an essential aspect of emergency medicine residency training. Prior studies have found a substantial variation in practice and policies with regard to ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia (UGRA) and this translates to the education of both residents and fellows.

Objectives

The objective was to describe the current state of UGRA education, trends, and barriers in emergency medicine residency and ultrasound fellowship programs in the United States.

Methods

A cross‐sectional survey was conducted via the Internet utilizing the Qualtrics software platform. It was distributed to ultrasound directors and program directors of both Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Osteopathic Association (AOA) accredited emergency medicine residency programs and ultrasound fellowships. Data analysis, cross‐tabulation, and subgroup analysis were performed utilizing the software.

Results

We received a total of 138 responses (response rate of 66.3%). There was substantial variability with regard to implementing UGRA education. Additionally, there was a trend correlating a greater likelihood of UGRA education among programs with more than two ultrasound faculty members. Faculty training is considered to be the greatest barrier to teaching UGRA to residents and fellows.

Conclusion

Resident and fellow education with regard to UGRA varies significantly among individual programs. Although there are currently no ACGME or AOA guidelines, nearly all residency programs believe that this is a skill that emergency physicians should learn. With the identification of key barriers and the need for an increased number of trained faculty, pain management utilizing UGRA may become an integral part to emergency medicine resident and fellow education.

Ultrasound is routinely utilized for procedural guidance in the emergency department (ED). Since its inclusion in the 2001 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine, bedside diagnostic and procedural ultrasound has become established as an integral and required component of the training of an emergency physician.1 Considered a best practice for central line placement, the use of ultrasound guidance confers the advantages of enhanced procedural success and patient safety and furthermore has transformed other procedures such as paracentesis, arthrocentesis, and nerve blocks.2, 3 Landmark‐guided peripheral nerve blocks have long been utilized for laceration repairs,4, 5 joint reductions,6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and pain control;12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 however, one study noted that more than 30% of nerve blocks fail if performed by anatomic landmarks alone. The addition of ultrasound guidance has made regional anesthesia procedures faster, more accurate, and more successful as a pain management modality.18 Despite a growing demand for training, effective teaching strategies for ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia (UGRA) procedures have yet to be established in the ED setting.

Amini et al.21, 22 found that there was substantial variation in UGRA practice and polices in academic EDs. Most frequently, UGRA procedures were performed for fracture management and laceration repair. The most commonly performed blocks are forearm nerve blocks and femoral nerve blocks, likely due to their relative ease and the breadth of medical evidence supporting their utility. Practice seems to be lagging behind for blocks that are more proximal and perceived to be more advanced, such as brachial plexus blocks, and this is largely due to educational gaps.

Understanding the ways in which residents are currently being taught UGRA skills will clarify the need and build a foundation for curriculum development. Little is known regarding the current UGRA instructive techniques being utilized at the program level. The aim of this study was to investigate the current state of UGRA education, as well as attitudinal trends and barriers to UGRA training in EM residency training programs.

Methods

A cross‐sectional study was designed to examine the current training practices in UGRA among academic institutions with emergency medicine residency training programs in the United States. Through an electronic survey, we collected information about educational methods, attitudes toward UGRA training, barriers to incorporating UGRA into the emergency ultrasound (EUS) curriculum, and presence of interdepartmental collaboration. The institutional review board at Johns Hopkins Hospital approved the study.

Participants

Participants were recruited from all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)‐ and American Osteopathic Association (AOA)‐approved emergency medicine residency programs in the United States between December 2015 and February 2016 (n = 208). The targeted respondent was the EUS director; in instances where the residency program had no ultrasound director, the residency program directors were contacted in their place. Contact information for ultrasound directors and program directors were extracted from American College of Emergency Physicians database, cross‐referenced with the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine database, and all contact information was verified verbally with the department's program coordinator by phone.

Protocol

A survey questionnaire was employed to measure respondent's attitudes, knowledge, opinions, and perspectives. A 20‐question survey consisting of multiple‐choice and free‐text elements was developed and reviewed by a content expert in ED‐performed UGRA, as well as a biostatistician. A pilot of the questionnaire was distributed to a small sample of reviewers similar to the study population to ensure that content, format, and intent of the instructions and responses were presented as intended. On average, the sample questionnaire took 2.5 minutes to complete. The survey was administered electronically through Qualtrics (http://www.qualtrics.com), a secure Web‐based survey research platform. E‐mail links to the survey with automated reminders were sent to all ACGME (n = 166) and AOA (n = 42) approved residency programs, and programs were subsequently contacted once by phone if no response was received. In several instances, there were multiple responders from a given program, usually the ultrasound director and the residency program director. When this occurred, only the data provided by the ultrasound director were included in the analysis.

Data Analysis

Survey responses were tracked on the Qualtrics platform and raw data were downloaded for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to report survey responses. Cross‐tabulations and subgroup analysis examined whether regional differences, program duration, affiliation, presence of a fellowship program, and number of ultrasound faculty had any correlation with UGRA implementation in resident and fellow education.

Results

Survey Respondents

Of the 208 programs, there were 152 total respondents from a total 138 programs, corresponding to a 66.3% total program response rate. There were 14 programs where more than one person responded. An additional 28 respondents did not complete the entire survey, so these responses were not included in the results. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of programs that responded to the survey. Among the total population of programs that responded, 69 programs (50%) were university based, 33 programs (24%) were community hospitals with university affiliation, and 36 programs (26%) were community hospitals.

Table 1.

Program Characteristics of Survey Respondents

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Duration/affiliation | |

| Allopathic 3 year | 95 (69%) |

| Allopathic 4 year | 29 (21%) |

| Osteopathic (all 4 year) | 14 (10%) |

| Dual accredited | 10 (7%) |

| EUS fellowship offered | 75 (54%) |

| Mean number of EUS faculty | 3.84 |

Training Environment

Among emergency medicine residency programs, there is variability in the required training in EUS and particularly UGRA. A total of 127 (92%) respondents require an ultrasound rotation for residents, 112 (82%) during intern year. A total of 119 (86%) offer an ultrasound elective for residents and 88 (64%) offer an elective for medical students. More than 70 programs (53%) that responded require 4 weeks of ultrasound training during residency, while only 25 (18%) programs required 2 weeks of training.

Three‐year programs were more likely to incorporate UGRA into their resident and fellow education than 4‐year programs (n = 73, 77% vs. n = 29, 71%). However, the data reflect all 4‐year programs, including all osteopathic programs. Only seven of 14 (50%) osteopathic programs responded that they incorporated UGRA into their resident curriculum. In fact, of the 4‐year programs that did not teach UGRA to residents and fellows, the osteopathic programs comprised 59% (n = 7) of the total results.

There was a trend toward decreased rates of UGRA training for residents and fellows in programs with fewer ultrasound faculty (Table 2). Subgroup analysis did not demonstrate any significant geographic or regional variations among programs that teach UGRA. Additionally, 91% (n = 68) of programs with ultrasound fellowships incorporated UGRA into their curriculum versus 53% (n = 33) of programs without fellowships.

Table 2.

Relationship Between EUS Faculty Numbers and Presence of UGRA Training Curriculum

| UGRA in resident or fellow education | Number of Core Ultrasound Faculty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1–2 | >2 | Total | |

| Yes | 2 | 35 | 65 | 102 |

| No | 1 | 23 | 9 | 33 |

| Total | 3 | 58 | 74 | 135 |

EUS = emergency ultrasound; UGRA = ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia.

Attitudes and Educational Practices

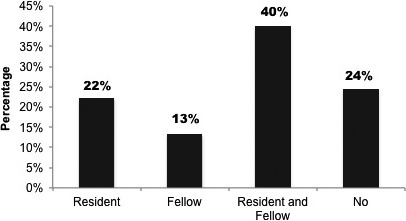

Overall, a great majority (n = 128, 93%) of EUS program leaders believe that UGRA is an important skill for residents, and almost all (n = 137, 99%) believe that fellows should acquire this skill. In practice, 75% (n = 102) of residents and fellows have formal education in UGRA during their training. The breakdown of programs can be seen in Figure 1. Fifty‐three percent of programs (n = 71) include UGRA in the ultrasound core content, while 30% (n = 40) provide this education during elective time. The majority of UGRA education is delivered through hands‐on training and didactics (n = 98, 73% and n = 93, 69% respectively), with a combined approach being most common among programs. Thirteen percent (n = 18) of programs had other ways of incorporating UGRA training, which varied from procedure labs, grand rounds, or interdepartmental conferences with anesthesia.

Figure 1.

Frequency of ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia training in emergency medicine residencies and emergency ultrasound fellowships.

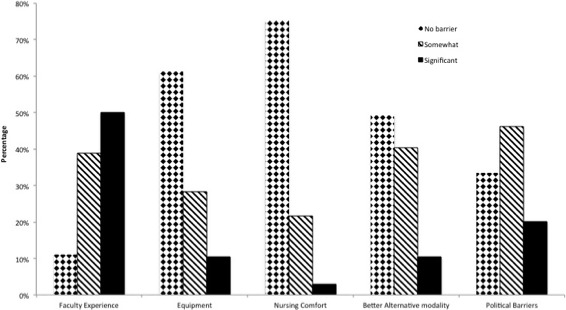

Obstacles to Resident and Fellow Education in UGRA

Among programs that provide training in UGRA, the majority of instruction is provided by ED attending physicians (n = 103, 77%). Notably, 43% (n = 58) of faculty respondents never received formal UGRA training, and 54% (n = 73) are dissatisfied with their current knowledge. This represented the most significant barrier to incorporating UGRA into the ultrasound curriculum. Figure 2 lists additional barriers to UGRA training and use in the ED. Notably, interdepartmental and political obstacles within the hospital were the second most common challenge. Interestingly, a majority of programs found that available equipment and nursing comfort were not at all barriers to implementing UGRA.

Figure 2.

Frequency of reported barriers to incorporating ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia into ED ultrasound curriculum.

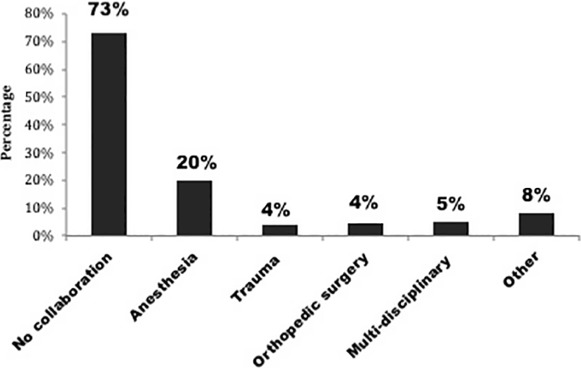

In most academic emergency medicine programs, “No interdepartmental collaboration” exists (n = 112, 76%). Among those with interdepartmental collaborations, those with anesthesia are most common, followed by orthopedic surgery, trauma surgery, and multidisciplinary collaborations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Most common interdepartmental ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia education collaborations with EM.

Discussion

This study was successful in describing the current state of UGRA education, attitudes, and barriers in emergency medicine residency and ultrasound fellowship programs in the United States.

Training Environment

Departments with EUS fellowship programs tended to prioritize UGRA initiatives in both fellow and resident education, although some felt that it was more pertinent for the fellows. This is in line with the inclusion of UGRA among the procedural skills within the Core Content of Clinical Ultrasonography Fellowship Training guidlines.26 Since academic departments with fellows frequently have a more robust cohort with advanced ultrasound expertise to contribute to the educational mission, this may be driving greater inclusion of UGRA in their programs.

The traditional model of “see one, do one, teach one” is still commonplace, but learners now have access to and desire for alternative modalities of procedural training. Simulation and cadaver labs are effective tools for UGRA education, but were not found to be widely utilized in EM training programs.22 The psychomotor feedback and opportunities for repetition provided by simulation have been shown to be a promising avenue for teaching UGRA to anesthesia and pediatrics residents.22, 23, 24, 25 UGRA focused simulators are commercially available but often at high expense; several low‐fidelity models exist with proven efficacy.27, 28

Attitudes and Educational Practices

The responsibility of EUS curriculum development and training primarily lies in the domain of the EUS faculty, and indeed our survey showed that programs with more EUS faculty members had more prolific UGRA curricula. Despite many faculty respondents reporting lack of formal training and dissatisfaction with their own knowledge base, they still uniformly expressed the desire for their fellows and residents to acquire these skills. A subset of EUS directors (n = 27, 20%) noted that they were championing relationships with their anesthesia departments and developing off‐service electives, joint conferences, and grand rounds talks on this topic.

Obstacles to Resident and Fellow Education in UGRA

The most significant barrier to routine UGRA incorporation cited was the lack of ED faculty experience. Survey results by Amini et al.22 revealed that only 7% of academic EDs had credentialing pathways in place for attending physicians. Knowing this, academic programs should consider building training and credentialing pathways for their faculty to gain more comfort and experience with UGRA. Self‐teaching and CME workshops seem to be the predominant method that physicians in practice are choosing to learn this skill.22 A well‐developed local UGRA curriculum would be useful to novice trainees and expert faculty alike.

The second most cited barrier was interdepartmental politics or lack of collaboration; as such, this could be a potential strategy to further develop EM‐based UGRA curriculum. Regional anesthesia is a required aspect of anesthesia residency training, and UGRA electives and training pathways are already commonplace in anesthesia programs.29 Since many EM residency programs have formal relationships with anesthesia for airway training, this could segue into an advanced regional anesthesia elective.

Limitations

Our method of investigation by survey was limited by response rate and responder bias. While attempts were made to contact all EM residency programs in the United States, responder bias may have led to a higher response rate from those programs with more established EUS departments, fellowships, or preexisting UGRA curricula. With any self‐reported survey, social desirability bias is introduced; the survey respondents may have answered questions in a manner that would be viewed favorably by others.30

Osteopathic programs posed a particular challenge in obtaining responses. AOA program underrepresentation in this survey means that their results should be interpreted with caution. Given that community EDs were not surveyed, the results of this study are not generalizable. This was not a validated survey, and thus there are fundamental limitations in the potential interpretation of the questions and the limited ability to draft a free‐text response.

Future Considerations

With the upcoming merger of allopathic and osteopathic programs, AOA programs will now be held to the same ultrasound training requirements as the ACGME programs. This may pose a significant challenge for the AOA programs with no current EUS director or well‐developed EUS curriculum. Additionally, there will be a need to assess performance of educational techniques and procedural learning curves of both physicians in training and in practice. Methods for assessing competency for UGRA procedures and credentialing pathways are topics for further investigation and development.

Ultrasound‐guided regional anesthesia may be a promising adjunct to acute pain management in the ED, particularly in the climate of a national opioid crisis and increased scrutiny of analgesic prescribing. Defining the role of UGRA in emergency medicine training and practice will be a topic for ongoing discussion and research.

AEM Education and Training 2017;1:158–164

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1. Lewiss RE, Pearl M, Nomura JT, et al. CORD‐AEUS: consensus document for the emergency ultrasound milestone project. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:740–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amini R, Kartchner JZ, Nagdev A, Adhikari S. Ultrasound‐guided nerve blockade in emergency medicine practice. J Ultrasound Med 2016;35:e37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Making Healthcare Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices Summary. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, No. 43. AHRQ Publication No. 01‐E058. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herring AA, Stone MB, Fischer J, et al. Ultrasound‐guided distal popliteal sciatic nerve block for ED anesthesia. Am J Emerg Med. 2011; 29:697.e3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Flores S, Herring AA. Ultrasound‐guided greater auricular nerve block for emergency department ear laceration and ear abscess drainage. J Emerg Med 2015;50:651–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herring AA, Stone MB, Frenkel O, Chipman A, Nagdev AD. The ultrasound‐guided superficial cervical plexus block for anesthesia and analgesia in emergency care settings. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:1263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blaivas M, Adhikari S, Lander L. A prospective comparison of procedural sedation and ultrasound‐guided interscalene nerve block for shoulder reduction in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:922–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liebmann O, Price D, Mills C, et al. Feasibility of forearm ultrasonography‐guided nerve blocks of the radial, ulnar, and median nerves for hand procedures in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:558–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stone MB, Wang R, Price DD. Ultrasound‐guided supraclavicular brachial plexus nerve block vs procedural sedation for the treatment of upper extremity emergencies. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:706–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tezel O, Kaldirim U, Bilgic S, et al. A comparison of suprascapular nerve block and procedural sedation analgesia in shoulder dislocation reduction. Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:549–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herring AA, Stone MB, Nagdev A. Ultrasound‐guided suprascapular nerve block for shoulder reduction and adhesive capsulitis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2011; 29:963.e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clattenburg E, Herring A, Hahn C, Johnson B, Nagdev A. ED ultrasound‐guided posterior tibial nerve blocks for calcaneal fracture analgesia. Am J Emerg Med 2015; 34:1183.e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frenkel O, Herring AA, Fischer J, Carnell J, Nagdev A. Supracondylar radial nerve block for treatment of distal radius fractures in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2011;41:386–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dickman E, Pushkar I, Likourezos A, et al. Ultrasound‐guided nerve blocks for intracapsular and extracapsular hip fractures. Am J Emerg Med 2015;34:586–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duchicela S, Lim A. Pediatric nerve blocks: an evidence‐based approach. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 2013;10:1–19; quiz 19–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frenkel O, Liebmann O, Fischer JW. Ultrasound‐guided forearm nerve blocks in kids: a novel method for pain control in the treatment of hand‐injured pediatric patients in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2015;31:255–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yoshida H, Yaguchi S, Matsumoto A, Hanada H, Niwa H, Kitayama M. A modified paravertebral block to reduce risk of mortality in a patient with multiple rib fractures. Am J Emerg Med 2015; 33:735.e3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thomas KP, Sainudeen S, Jose S, Nadhari MY, Macaire PB. Ultrasound‐guided parasternal block allows optimal pain relief and ventilation improvement after a sternal fracture. Pain Ther 2016;5:115–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marhofer P, Schrogendorfer K, Koinig H, Kapral S, Weinstabl C, Mayer N. Ultrasonographic guidance improves sensory block and onset time of three‐in‐one blocks. Anesth Analg 1997;85:854–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barrington MJ, Kluger R. Ultrasound guidance reduces the risk of local anesthetic systemic toxicity following peripheral nerve blockade. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2013;38:289–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Amini R, Adhikari S, Fiorello A. Ultrasound competency assessment in emergency medicine residency programs. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:799–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amini R, Kartchner JZ, Nagdev A, Adhikari S. Ultrasound‐guided nerve blocks in emergency medicine practice. J Ultrasound Med 2016;35:731–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Udani AD, Kim TE, Howard SK, Mariano ER. Simulation in teaching regional anesthesia: current perspectives. Local Reg Anesth 2015;8:33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bretholz A, Doan Q, Cheng A, Lauder G. A presurvey and postsurvey of a web‐ and simulation‐based course of ultrasound‐guided nerve blocks for pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012;28:506–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Broking K, Waurick R. How to teach regional anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2006;19:526–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lewiss RE, Tayal VS, Hoffmann B, et al. The core content of clinical ultrasonography fellowship training. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sparks S, Evans D, Byars D. A low cost, high fidelity nerve block model. Crit Ultrasound J 2014; 6:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Micheller D, Chapman MJ, Cover M, et al. A low fidelity, high functionality, inexpensive ultrasound‐guided nerve block model. Clin J Em Med 2016;1:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Helwani MA, Saied NN, Asaad B, et al. The current role of ultrasound use in teaching regional anesthesia: a survey of residency programs in the United States. Pain Med 2012;10:1342–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paulhus DL.Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes In: Measurement and Control of Response Biases. San Diego: Academic Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]