Abstract

Background

Although low alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels have been associated with poor outcomes in the elderly population, the determinants subtending this association have been poorly explored. To gain insight into this topic, we analyzed data from a prospective population-based database (InCHIANTI study) in which frailty, disability, sarcopenia, and pyridoxine levels were systematically assessed.

Methods

Data are from 765 participants aged more than 65 years (mean age 75.3 years, women 61.8%), without chronic liver disease, malignancies, or alcohol abuse. Frailty was defined according to Fried criteria, sarcopenia through peripheral Quantitative-Computed-Tomography (lowest gender-specific tertile of the residuals of a linear regression of muscle mass from height and fat mass), and disability as self-reported need for help in at least one basic daily living activity. Associations of ALT with overall and cardiovascular mortality were assessed by Cox-models with time-dependent covariates.

Results

ALT activity was inversely associated with frailty, sarcopenia, disability, and pyridoxine deficiency; however, higher ALT was confirmed to be protective with respect of overall and cardiovascular mortality even in multiple-adjusted models including all these covariates (overall: hazard ratio [HR] 0.98 [0.96–1], p = .02; cardiovascular: 0.94 [0.9–0.98], p < .01). The association between ALT activity and mortality was nonlinear (J-shaped), and subjects in the lower quintiles of ALT levels showed a sharply increased overall and cardiovascular mortality.

Conclusions

These results suggest that reduced ALT levels in older individuals can be considered as a marker of frailty, disability, and sarcopenia, and as an independent predictor of adverse outcomes. The possible relationship between reduced ALT and impaired hepatic metabolic functions should be explored.

Keywords: Transaminases, Outcomes, Nonalcoholic fatty liver, Mortality

Reliable clinical and laboratory markers have been identified that predict morbidity and mortality in older patients. While diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, chronic renal failure, and chronic pulmonary disease, are among the strongest clinical predictors of mortality (1–3), low serum albumin and cholesterol levels have emerged as the principal laboratory parameters that predict multiple adverse outcomes in this age group (4,5).

While the activity of liver enzymes is routinely assessed in clinical practice to screen for liver dysfunction and pathology, in recent studies liver enzymes activity has been identified as a predictor of nonliver-related morbidity and mortality. A growing number of studies in older populations reported that low alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels are associated with higher total and cardiovascular mortality (6–8). ALT is predominantly found in the liver, and it catalyzes the reversible transformation of α-keto-acids into amino-acids by transfer of amino groups, thereby facilitating basic metabolic steps. It is released in the blood by damaged hepatocytes and higher activity indicates liver disease. Thus, an inverse association has been observed between ALT levels and mortality seems counterintuitive. A progressive reduction of ALT levels with aging has been described (9,10); however, the inverse association between ALT and mortality was always found to be independent from age (6–8,11,12). Potentially explaining these findings, there is some evidence that low ALT is a biomarker for frailty, disability, sarcopenia, and malnutrition, which herald a shorter life span (6–8,11,12). Moreover, since ALT activity is consistently associated with body mass index (BMI), likely due to liver damage determined by nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (13), the lower BMI levels in subjects with low ALT activity may reflect a worse nutritional status. In this regard, it should be considered that pyridoxal-5’-phosphate is a coenzyme for transaminases, and a reduction of ALT levels may express pyridoxine deficiency, either alone or as part of malnutrition.

The majority of previous studies that investigated ALT levels in relation to mortality in older persons did not account for many of the potential confounders and mediators that can explain this association. Therefore, we used data from the “Invecchiare inChianti” (Aging in the Chianti area, InChianti) study, a prospective population-based study of older persons in which frailty, disability, sarcopenia and pyridoxine levels, together with ALT activity, were comprehensively assessed, to explore the biological determinants of the association between ALT activity and mortality.

Methods

Data Source

The InCHIANTI study is a prospective, population-based study of randomly selected 1,453 subjects from the city registries of Greve in Chianti and Bagno a Ripoli in the Chianti area, Tuscany, Italy. The project was designed by the Laboratory of Clinical Epidemiology of the Italian National Research Council on Aging (INRCA, Florence, Italy), and was aimed at investigating the factors contributing to the development of late-life disability. The Italian National Institute of Research and Care on Aging Ethical Committee ratified the study protocol and all participants provided written consent to participate. Eligible subjects were firstly interviewed at their homes using a structured questionnaire aimed at investigating their health status, and their physical and cognitive performance. The interview was followed by physical examination and blood tests at study clinic. History of chronic liver disease and of other comorbid diseases was ascertained examining clinical history and medical records. Baseline evaluation started in 1998 and participants were followed-up at 3 and 6 years (2001–2003 and 2004–2006), undergoing repeated phlebotomy, laboratory testing, and physical performance assessment. A detailed description of the sampling procedure and data collection method has been previously published (14).

Sample Selection and Variable Assessment

From the original study population with available laboratory data at baseline (N = 1,434), we selected participants aged more than 65 years and with an available ALT determination (N = 1,043). Thereafter, we excluded those with chronic liver disease or malignancies (N = 71), and those who reported chronic alcohol assumption more than 40 g/day if male or 20 g/day if female (N = 207). The final sample size for our analysis consisted of 765 subjects. Vital status was available for all participants up to April 2010. Causes of death were registered through the International Classification of Disease (ICD)-9 code. Cardiovascular death was defined with ICD-9 codes ranging from 390 to 459. Medications were recorded through the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification code, and, according to previous studies, the following were considered drugs potentially leading to alteration of ALT values: systemic glucocorticoids, serum lipid-reducing agents, penicillins, β-lactams, tetracyclines, quinolones, antimycotics, antimycobacterials, antivirals, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressant, sex hormones and oral contraceptives, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and immunosuppressive agents. ALT was measured using a commercial kit (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) based on the UV kinetic method and a Roche analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH); the test does not include the addition of pyridoxine. Normal values of the test were 10–40 U/L. Pyridoxine was determined only at baseline using a commercial high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay with fluorescence detection (Vitamin B6 HPLC-application; Immundiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany), and patients with less than 5 ng/mL were considered deficient, according to the lower limit of normality of the test. Frailty indicators were assessed according to Fried and colleagues’ criteria (15). By counting the number of the Fried’s indicators, frailty was defined if ≥3 were present. When performance measures were not collected, the anamnestic frailty phenotype with cutoff ≥2 was considered, since it was shown to retain similar discriminative capacities of the original Fried’s frailty phenotype (16). Physical activity was quantified based on the intensity (light, moderate, or severe) and the time per week (1–2 hours, 2–4 hours, or >4 hours) spent by the subject performing exercise. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was estimated through the Crockcroft-Gault formula. Smoking habit was measured in pack-years. Disability was defined as loss of one of the basic activities of daily living: dressing, moving in and out of bed, using the toilet, washing, eating, and control urine and fecal continence (17). Sarcopenia was assessed through a right leg peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography, that evaluated the cross-sectional muscle and fat areas of the calf scanned at the 66% of the tibial length starting from the tibiotarsal joint. Sarcopenia was, then, defined according to the lowest gender-specific tertile of the residuals of a linear regression model that predicted the dependent variable muscle mass area (in cm2) from height (in cm) and fat mass area (log value of cm2; independent variables) (18). Data on ALT, comorbidities, BMI, sarcopenia, frailty, and disability were collected also at the first and second follow-up, when available.

Statistical Analysis

For descriptive purposes, baseline characteristics of the study population were compared according to ALT quintiles using analysis of variance test or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables, as appropriate, and by χ2 test for categorical variables. The association between ALT and incidence of frailty, sarcopenia, and disability was estimated through log-normal regressions and expressed as 6-year risk ratios (RR). Conversely, to evaluate the longitudinal association between ALT (as continuous variable and, then, categorized by quintiles) and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular death we used Cox proportional hazard regressions in which ALT and all the other covariates (excluding pyridoxine deficiency) were modeled as time-dependent. Four models were fitted for each outcome: unadjusted, age-sex adjusted and two multiple-adjusted models including BMI, comorbidities (congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, respiratory disease), smoke, physical activity level, frailty, sarcopenia, disability, and pyridoxine deficiency. Of note, these latest covariates were all found to be significantly associated (p < .10) with outcomes in univariate analyses, and the proportional hazard assumption of these models was tested through the Schoenfeld residuals. Survival curves were analyzed according to ALT groups and compared by the log-rank test. Statistical significance was assumed at p less than 0.05. All analysis were performed using R 3.2.3 software for Mac (R Foundation).

Results

The general characteristics of the study population, overall and according to quintiles of serum ALT activity, are reported in Table 1. Twenty subjects (2.6%) were found with elevated ALT levels according to the upper normal limit of the test, that is, 40 U/L. At baseline, 164 (21.43%) subjects were taking medications potentially leading to elevation of ALT levels, but their mean ALT value was not significantly different compared to subject who were not taking them (p = .23). Subjects with abnormal ALT levels or taking potentially hepatotoxic drugs were not excluded from study population since sensitivity analyses after their exclusion left the regression coefficients almost completely unchanged (data not shown).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables of Interest According to Quintiles of ALT at Baseline

| All | ALT Quintiles | p** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <14 | (14, 16) | (16, 19) | (19, 24) | ≥24 | |||

| N | 765 | 204 | 120 | 146 | 155 | 140 | - |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 75.3 (7.5) | 79.1 (7.9) | 76.8 (7.1) | 74.3 (6.8) | 72.9 (6.3) | 72.2 (6.7) | <.001 |

| Sex (Female), % | 61.8% | 70.1% | 66.7% | 66.4% | 56.1% | 47.1% | <.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.4 (4.1) | 26.5 (4) | 27.2 (3.8) | 27.1 (3.9) | 27.8 (3.9) | 28.8 (4.3) | <.001 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.916 (0.07) | 0.911 (0.07) | 0.909 (0.066) | 0.905 (0.065) | 0.922 (0.075) | 0.933 (0.069) | <.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 67.3% | 67.2% | 69.2% | 66.4% | 65.8% | 68.6% | ns |

| Diabetes Mellitus, % | 12.5% | 10.8% | 12.5% | 8.2% | 15.5% | 16.4% | ns |

| COPD, % | 10.3% | 10.8% | 11.7% | 5.5% | 11.6% | 12.1% | ns |

| CHF,% | 25.8% | 27.9% | 31.7% | 19.9% | 25.8% | 23.6% | ns |

| ALT >UNL (40 U/L), % | 2.6% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 217.3 (39.6) | 211.2 (38.1) | 216.3 (39.5) | 225.2 (39.3) | 221.7 (41.7) | 213.8 (38.6) | <.01 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 136.5 (34.5) | 131.4 (31.9) | 136.2 (34.3) | 142.8 (34.7) | 140.6 (37.7) | 132.9 (33.5) | .01 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 127.1 (70) | 121 (64.8) | 118 (51.3) | 126.6 (61.2) | 128.7 (77.4) | 142.4 (87.3) | ns |

| eGFR (mL/min), mean (SD) | 63.9 (19) | 55.3 (17.5) | 59.8 (18) | 65.1 (18) | 68.5 (17.5) | 72.7 (18.9) | <.001 |

| Pyridoxine (ng/mL), mean (SD) | 6.7 (6.6) | 5.4 (6.2) | 5.9 (4.2) | 7 (3.7) | 7.6 (7.9) | 7.8 (8.9) | <.001 |

| Smoke (Pack-year), mean (SD) | 9.4 (17.9) | 8.4 (17.3) | 9.3 (18.7) | 8.9 (17.2) | 9.8 (19.3) | 11 (17.5) | ns |

| Physically Active*, % | 34.3% | 24.6% | 32.8% | 36.6% | 38.7% | 42.4% | <.01 |

| Frailty, % | 11.1% | 18.1% | 15% | 8.2% | 7.1% | 5% | <.001 |

| Disability, % | 8.9% | 16.7% | 8.3% | 5.5% | 3.9% | 7.1% | <.001 |

| Sarcopenia, % | 11.6% | 20.5% | 16.5% | 9.1% | 8.3% | 1% | <.001 |

| Follow-up (months), mean (SD) | 92.2 (31.5) | 80.8 (36.1) | 87.1 (33.7) | 98.3 (26.9) | 98.8 (25.2) | 99.5 (27.5) | <.001 |

| Deaths, % | 38.3% | 56.9% | 47.5% | 29.5% | 27.7% | 24.3% | <.001 |

| CV-deaths, % | 18.2% | 30.8% | 23.3% | 12.9% | 10% | 9.6% | <.001 |

Note: ALT = Alanine aminotransferase; BMI = Body mass index; COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF = Congestive heart failure; CV = Cardiovascular; eGFR = Estimated glomerular filtration rate; LDL = Low density lipoprotein; UNL = Upper normal limit.

*Physical activity at least moderate exercise once or twice a week or light exercise more than 4 times per week. **Comparison carried out by analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate, for continuous variable or chi-square test for categorical variable.

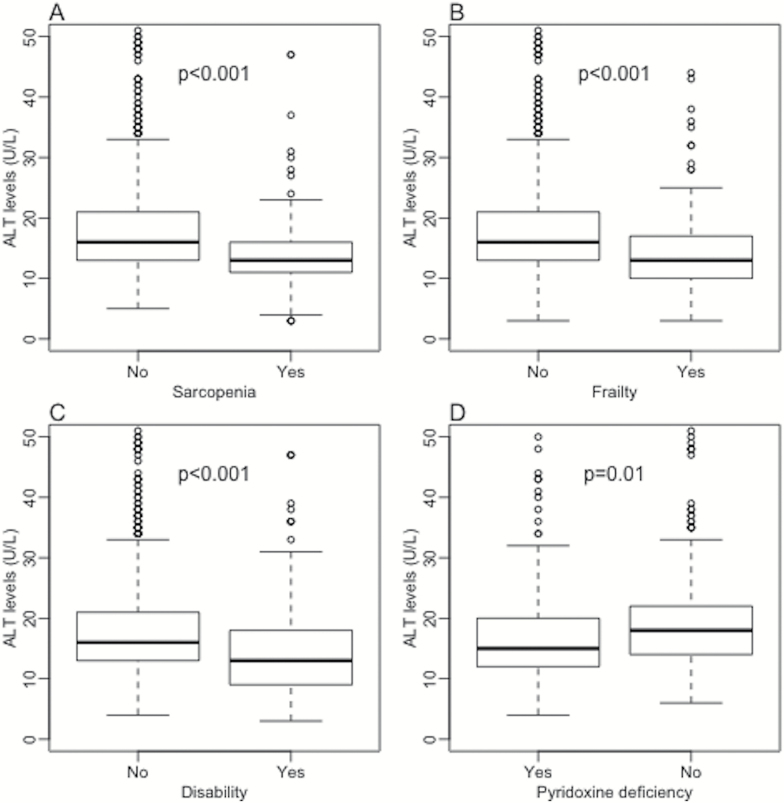

ALT activity was inversely associated with age and female sex, while it was directly associated with BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, estimated glomerular filtration rate, physical activity, pyridoxine levels, total and LDL cholesterol. The association between ALT levels and triglycerides was not significant. Lower quintiles of ALT levels showed a higher overall and cardiovascular mortality and, consistently, patients in these groups presented a shorter mean follow-up. As presented in Figure 1, individuals with the frail phenotype, and those with disability, sarcopenia, and reduced pyridoxine levels, showed significantly lower serum ALT levels. Moreover, subjects with baseline ALT less than 19 U/L (lowest two quintiles) showed significant 6-year RRs of developing frailty (RR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3–2.9), and disability (RR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2–3.7), while the association with incident sarcopenia was not significant (RR 1.1, 95% CI 0.5–2.2).

Figure 1.

ALT activity distributions according to presence or absence of frailty (A), sarcopenia (B), disability (C), and pyridoxine deficiency (D). ALT = Alanine aminotransferase.

After a mean follow-up of 92.2 ± 31.5 months, 293 subjects had died, 135 (46%) due to cardiovascular events. When ALT levels were tested for prediction of mortality according to a linear model (Table 2), each unit of ALT activity was significantly associated with a 2%–8% reduction of the risk of overall and cardiovascular mortality, both in the unadjusted and in the multiple-adjusted models.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazard models for ALT activity and overall and cardiovascular mortality.

| Overall Mortality | Cardiovascular Mortality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT | HR | 2.5% | 97.5% | p | HR | 2.5% | 97.5% | p |

| Unadjusted | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.97 | <.01 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.95 | <.01 |

| Age-sex adjusted | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1 | .03 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1 | .07 |

| m-adjusted mod1 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | .01 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.98 | <.01 |

| m-adjusted mod2 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1 | .02 | 0.94 | 0.9 | 0.98 | <.01 |

Note: Model 1 including age, sex, BMI, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, smoke, physical activity, and glomerular filtration rate; Model 2 including model 1 plus sarcopenia, frailty, disability, and pyridoxine. ALT = Alanine aminotransferase; HR = Hazard ratio.

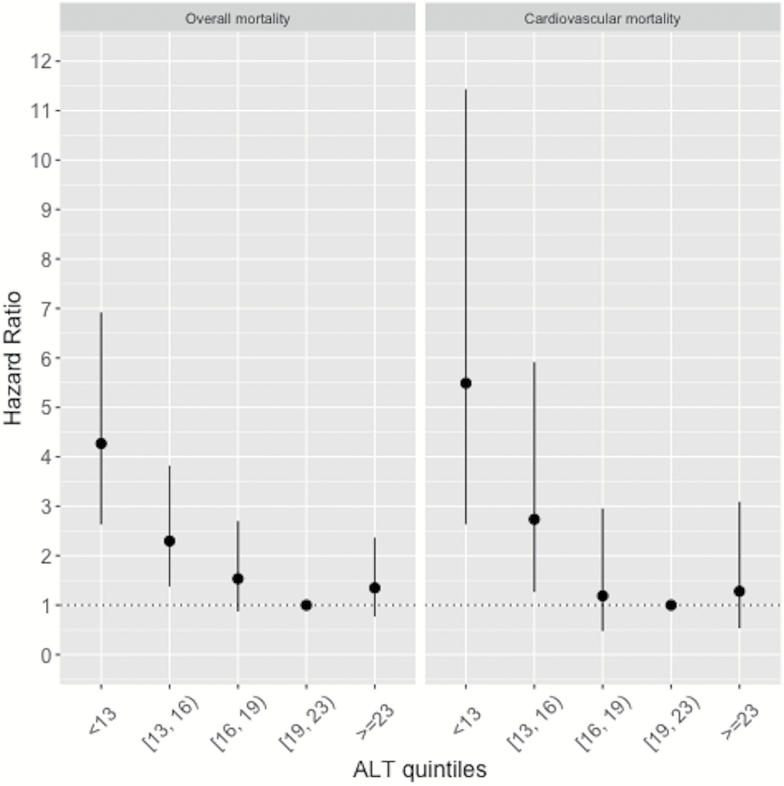

Figure 2 illustrates hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of ALT activity quintiles for overall and cardiovascular mortality. The fourth quintile of ALT concentrations, associated with the lowest mortality, was chosen as reference. The association between ALT activity and mortality was nonlinear, J-shaped. Indeed, subjects in the two lower quintiles of ALT levels showed a significantly increased overall (I quintile: HR 4.3, 95% CI 2.6–6.9; II quintile: HR 2.3, 95% CI 1.4–3.8) and cardiovascular mortality (I quintile: HR 5.5, 95% CI 2.6–11.4; II quintile: HR 2.7, 95% CI 1.3–5.9), and those in the fifth quintile presented a non-significant increase of the risk. For the sake of completeness, also abnormally elevated ALT levels (2.6%) were tested and not found to be associated with overall or cardiovascular mortality (overall: HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.29–1.68; cardiovascular: 0.30, 95% CI 0.04–2.13).

Figure 2.

Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for overall and cardiovascular mortality according to quintiles of ALT levels. ALT = Alanine aminotransferase.

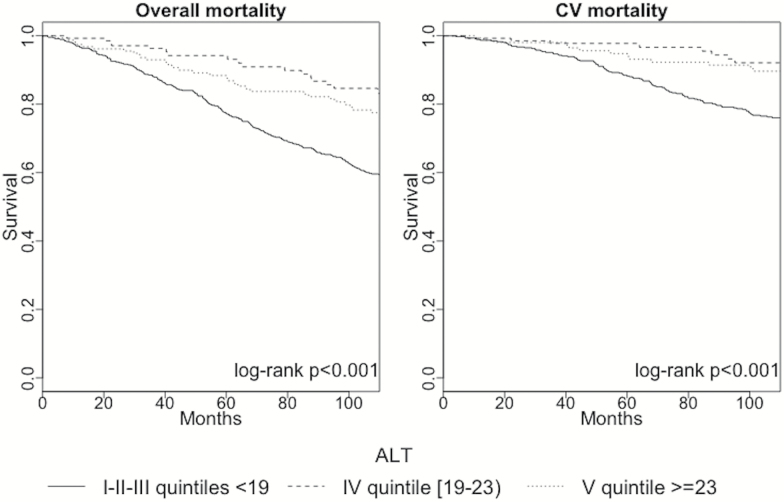

Due to their worst prognosis, the first three quintiles of ALT activity were grouped and the survival curve of these subjects analyzed with respect to those in the fourth and in the fifth quintile, respectively. As presented in Figure 3, subjects with ALT less than 19 I.U. showed a significantly reduced survival with respect to the other two groups.

Figure 3.

Survival curves of patients belonging to I-II-III, IV, and V quintiles of ALT activity. ALT = Alanine aminotransferase; CV = Cardiovascular.

Discussion

The present results, obtained in participants aged 65 years or older from the InChianti study, confirm the inverse association between ALT and total and cardiovascular mortality in the elderly population. Confirming previous observations, ALT was associated with frailty, disability, sarcopenia, and low pyridoxine levels. However, the association between low ALT and mortality was still statistically significant after adjusting for all these possible confounders. While further studies are needed to individuate the missing biological determinants of this relationship, we think that there is already sufficient evidence to consider low ALT levels as a risk factor for adverse outcomes in older patients.

As previously mentioned, in the last years, there has been increasing attention to liver enzymes as possible predictors of cardiovascular or overall mortality. Indeed, liver test determination is widespread, cheap, and, excluding specific situations, quite reproducible. Consistent with the finding that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is the first cause of liver enzyme abnormalities in the general population (19), serum ALT and γ-glutamyl-transferase levels have been strongly associated with metabolic factors, such as BMI, glucose, total cholesterol, and triglycerides (20–24). Following this same line of interpretation, as surrogate marker of metabolic syndrome, oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and cardiovascular disease risk, γ-glutamyl-transferase showed almost linear dose-response relationships with cardiovascular and overall mortality risk in different previous studies (7,12,25–27). In contrast to this strong body of evidence regarding γ-glutamyl-transferase, studies of community or population-based samples investigating the association of ALT with mortality are less congruent. Indeed, while some epidemiological studies in Europe, United States, and Asia found elevated ALT levels to be associated with higher mortality risk (28–31), recent cohort studies in the elderly population have shown consistently that lower ALT serum concentrations are associated with increased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality (Supplementary Table 1) (6–8,32). One possible explanation for this apparent paradox is that serum ALT levels may have different meaning in different age groups. By analyzing a cohort of more than 300,000 participants who had undergone medical check-ups, Oh and colleagues found serum ALT levels to be linearly associated with all-cause mortality in subjects less than 60 years, while the association was nonlinear, or better U-shaped, in subjects ≥60 years (33). A nonlinear, J-shaped, relationship between ALT and mortality was observed in our study as well in the study by Elinav and colleagues in a population of patients aged ≥70 years (6). It has been speculated that, while in younger subjects serum ALT essentially marks the metabolic risk, in older subjects free of specific liver diseases reduced ALT levels mostly represent a bio-marker for frailty, disability, sarcopenia, and/or reduced pyridoxine levels (6–8,11,12). However, this hypothesis was never empirically tested. Williams and colleagues did not find association between ALT levels and the eight domains from the SF-36 questionnaire (physical functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, energy/fatigue, emotional wellbeing, social functioning, pain, and general health) (12). Frailty, as defined according to the frailty criteria used in the Cardiovascular Health Study (34), was individuated as the confounding factor mediating the inverse relationship between ALT and mortality by Le Couteur and colleagues, while lean body mass was not associated with ALT activity (8).

One of the strengths of the present study is that all the possible confounders which have been previously hypothesized for the association between ALT and mortality have been assessed and verified. It is confirmed that frailty, disability, sarcopenia, and pyridoxine deficiency are associated with reduced ALT serum concentrations, but the association of lower ALT with poor prognosis is still maintained after adjusting for these potential confounders. These results were confirmed when statistics was calibrated to the nonlinear relationship between ALT and mortality risk, and patients in the lower three quintiles of ALT activity showed and almost doubled risk of overall and cardiovascular mortality compared to those in the fourth quintile, which was chosen as the reference group. Another strength of the present work is that, differently from all previous similar studies, ALT was not determined only at baseline but also other two times during follow-up, and a time-dependent analysis was carried-out. This approach significantly limits possible misclassifications due to ALT variation during follow-up.

Clearly, independent association does not imply causality, nor there are easily discernable mechanisms by which a reduced ALT activity would contribute to the increased mortality risk. It seems more plausible to suppose that other unrecognized confounders act on the background of this relationship. It has already been speculated that low ALT activity may better represent hepatic rather than overall frailty (7), and hepatic aging (6). Experimental models have demonstrated that hepatic aging is associated with greater oxidative stress and hepatic cell apoptosis (35), which, if exaggerated, may lead to a decrease in total hepatocyte number and to lower ALT activity. Since the liver has a central metabolic role and protects the body from circulating endogenous and exogenous toxins, any change in liver function has potential implications on extrahepatic systems and on overall health. However, it should be noted that, to date, there are no studies correlating ALT activity with hepatic metabolic functions.

This study has also some limitations. The principal is that participants were not screened for hepatitis B "s" antigen (HBsAg) and anti hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) antibodies, and only subjects with known history of liver disease were excluded. Actually, this limitation, which has been faced by previous similar studies (7,8,11), should be expected to weaken, rather than to contribute to, the inverse association between ALT and mortality. Another limitation of the study is being a retrospective analysis of data, in which potential biases cannot be ruled out and, as already discussed, causality cannot be claimed.

In conclusion, by conducting a time-dependent analysis of different ALT determinations in a population of subjects aged 65 years and older from the InChianti study, the present study confirms that low ALT levels are associated with increased overall and cardiovascular mortality in elderly patients. The independence of the association between ALT and outcomes, in the first study simultaneously assessing frailty, disability, sarcopenia, and pyridoxine levels, revamps the interest on the possible biological determinants of this relationship. Mainly, these results confirm that there is already sufficient evidence to consider reduced ALT activity in older individuals as a marker of frailty, disability, and sarcopenia, and as a predictor of adverse outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data is available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences online.

Funding

The InCHIANTI study baseline (1998 and 2000) was supported as a “targeted project”(ICS110.1/RF97.71) by the Italian Ministry of Health, and in part by the National Institute on Aging (Contracts: 263 MD 9164 and 263 MD 821336). The Follow-up 1 (2001 and 2003) was funded by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contracts: N.1AG-1-1 and N.1-AG-1-2111); the Follow-up 2 and 3 studies (2004 and 2010) were financed by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contract: N01-AG-5-0002). The study was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Campbell AJ, Diep C, Reinken J, McCosh L. Factors predicting mortality in a total population sample of the elderly. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1985;39:337–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fried LP, Kronmal RA, Newman AB, et al. Risk factors for 5-year mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA. 1998;279:585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Psaty BM, Furberg CD, Kuller LH, et al. Traditional risk factors and subclinical disease measures as predictors of first myocardial infarction in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1339–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Volpato S, Leveille SG, Corti MC, Harris TB, Guralnik JM. The value of serum albumin and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in defining mortality risk in older persons with low serum cholesterol. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1142–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schatz IJ, Masaki K, Yano K, Chen R, Rodriguez BL, Curb JD. Cholesterol and all-cause mortality in elderly people from the Honolulu Heart Program: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358:351–355. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05553-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elinav E, Ackerman Z, Maaravi Y, Ben-Dov IZ, Ein-Mor E, Stessman J. Low alanine aminotransferase activity in older people is associated with greater long-term mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1719–1724. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00921.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koehler EM, Sanna D, Hansen BE, et al. Serum liver enzymes are associated with all-cause mortality in an elderly population. Liver Int. 2014;34:296–304. doi:10.1111/liv.12311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Le Couteur DG, Blyth FM, Creasey HM, et al. The association of alanine transaminase with aging, frailty, and mortality. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:712–717. doi:10.1093/gerona/glq082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Gallo P, Piccinocchi G, et al. Determinants of alanine aminotransferase levels in a large population from Southern Italy: relationship between alanine aminotransferase and age. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:909–915. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2014.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elinav E, Ben-Dov IZ, Ackerman E, et al. Correlation between serum alanine aminotransferase activity and age: an inverted U curve pattern. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2201–2204. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41822.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramaty E, Maor E, Peltz-Sinvani N, et al. Low ALT blood levels predict long-term all-cause mortality among adults. A historical prospective cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:919–921. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2014.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams KH, Sullivan DR, Nicholson GC, et al. Opposite associations between alanine aminotransferase and γ-glutamyl transferase levels and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes: analysis of the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) study. Metabolism. 2016;65:783–793. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marchesini G, Moscatiello S, Di Domizio S, Forlani G. Obesity-associated liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11 suppl 1):S74–S80. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, et al. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1618–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pedone C, Costanzo L, Cesari M, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L, Antonelli Incalzi R. Are performance measures necessary to predict loss of independence in elderly people?J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:84–89. doi:10.1093/gerona/glv096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Newman AB, Kupelian V, Visser M, et al. ; Health ABC Study Investigators. Sarcopenia: alternative definitions and associations with lower extremity function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1602–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pendino GM, Mariano A, Surace P, et al. ; ACE Collaborating Group. Prevalence and etiology of altered liver tests: a population-based survey in a Mediterranean town. Hepatology. 2005;41:1151–1159. doi:10.1002/hep.20689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Piton A, Poynard T, Imbert-Bismut F, et al. Factors associated with serum alanine transaminase activity in healthy subjects: consequences for the definition of normal values, for selection of blood donors, and for patients with chronic hepatitis C. MULTIVIRC Group. Hepatology. 1998;27:1213–1219. doi:10.1002/hep.510270505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prati D, Taioli E, Zanella A, et al. Updated definitions of healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:1–10. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu WC, Wu CY, Wang YJ, et al. Updated thresholds for serum alanine aminotransferase level in a large-scale population study composed of 34346 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:560–568. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kariv R, Leshno M, Beth-Or A, et al. Re-evaluation of serum alanine aminotransferase upper normal limit and its modulating factors in a large-scale population study. Liver Int. 2006;26:445–450. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kang HS, Um SH, Seo YS, et al. Healthy range for serum ALT and the clinical significance of “unhealthy” normal ALT levels in the Korean population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:292–299. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kunutsor SK, Apekey TA, Seddoh D, Walley J. Liver enzymes and risk of all-cause mortality in general populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:187–201. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Breitling LP, Claessen H, Drath C, Arndt V, Brenner H. Gamma-glutamyltransferase, general and cause-specific mortality in 19,000 construction workers followed over 20 years. J Hepatol. 2011;55:594–601. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kunutsor SK, Apekey TA, Khan H. Liver enzymes and risk of cardiovascular disease in the general population: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Atherosclerosis. 2014;236:7–17. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schindhelm RK, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, et al. Alanine aminotransferase predicts coronary heart disease events: a 10-year follow-up of the Hoorn Study. Atherosclerosis. 2007;191:391–396. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee TH, Kim WR, Benson JT, Therneau TM, Melton LJ., 3rd Serum aminotransferase activity and mortality risk in a United States community. Hepatology. 2008;47:880–887. doi:10.1002/hep.22090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim HC, Nam CM, Jee SH, Han KH, Oh DK, Suh I. Normal serum aminotransferase concentration and risk of mortality from liver diseases: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2004;328:983. doi:10.1136/bmj.38050.593634.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nakamura K, Okamura T, Kanda H, Hayakawa T, Okayama A, Ueshima H; Health Promotion Research Committee of the Shiga National Health Insurance Organizations The value of combining serum alanine aminotransferase levels and body mass index to predict mortality and medical costs: a 10-year follow-up study of National Health Insurance in Shiga, Japan. J Epidemiol. 2006;16:15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ford I, Mooijaart SP, Lloyd S, et al. The inverse relationship between alanine aminotransferase in the normal range and adverse cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular outcomes. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1530–1538. doi:10.1093/ije/dyr172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Oh CM, Won YJ, Cho H, et al. Alanine aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyl transferase have different dose-response relationships with risk of mortality by age. Liver Int. 2016;36:126–135. doi:10.1111/liv.12879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blyth FM, Rochat S, Cumming RG, et al. Pain, frailty and comorbidity on older men: the CHAMP study. Pain. 2008;140:224–230. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martin R, Fitzl G, Mozet C, Martin H, Welt K, Wieland E. Effect of age and hypoxia/reoxygenation on mRNA expression of antioxidative enzymes in rat liver and kidneys. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:1481–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.