Abstract

While genetic testing gains adoption in specialty services such as oncology, neurology, and cardiology, use of genetic and genomic testing has yet to be adopted as widely in primary care. The purpose of this study is to identify and compare patient and primary care provider (PCP) expectations of genetics services in primary care. Patient and PCP perspectives were assessed through a mixed-method approach combining an online survey and semi-structured interviews in a primary care department of a large academic medical institution. A convenience sample of 100 adult primary care patients and 26 PCPs was gathered. The survey and interview questions focused on perceptions of genetic testing, experience with genetic testing, and expectations of genetic services in primary care. Patients felt that their PCP was knowledgeable about genetic testing and expected their PCP to be the first to recognize a need for genetic testing based on family history. Nonetheless, patients reported that PCPs rarely used family history information to discuss genetic risks or order testing. In contrast, PCPs felt uncertain about the clinical utility and scientific value of genetic testing. PCPs were concerned that genetic testing could cause anxiety, frustration, discrimination, and reduced insurability, and that there was unequal access to testing. PCPs described themselves as being “gatekeepers” to genetic testing but did not feel confident or have the desire to become experts in genetic testing. However, PCPs were open to increasing their working knowledge of genetic testing. Within this academic medical center, there is a gap between what patients expect and what primary care providers feel they are adequately prepared to provide in terms of genetic testing services.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12687-017-0349-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Genetics, Patient-centered care, Physician decision support, Primary care, Personalized medicine

Introduction

As US healthcare increasingly emphasizes patient-centered and personalized medicine, the availability and use of genetic and genomic tests has grown rapidly (Hall et al. 2014; Vassy et al. 2014). Simultaneously, both non-genetics healthcare providers and the general public are becoming more aware of and interested in genetic testing. However, visits with genetics specialists are often limited by both geography and by limited availability of appointments. While genetic testing has been adopted to some extent in specialty services such as oncology (Tung 2011), neurology (Pitceathly 2016), and cardiology (Wolf et al. 2016), genetic testing has yet to be widely adopted in primary care. Despite this, primary care providers are increasingly being asked to perform genetics “triage” and provide some basic genetics services themselves.

Over 90% of healthcare visits are to primary care physicians (PCPs) (Edwards et al. 2014). Patients build relationships with their PCPs, are followed over time, and rely on their PCPs for guidance in making medical decisions. These features make primary care an ideal setting to assess health risks and implement preventive strategies using genomic data (David et al. 2015). Moreover, some providers have called for greater integration of genetics into primary care (David et al. 2015; Hamburg and Collins 2010), but it is unclear how primary care patients and physicians expect that call to be heeded. Limited studies from Europe indicate that patients might prefer a primary care setting for genetic testing. For example, Dutch chronic disease patients ranked PCPs above both written materials and specialists as their preferred source of information (Morren et al. 2007). An older qualitative study in the UK of 19 patients with a family history of colorectal cancer came to a similar conclusion (Emery et al. 1998). However, there are no data as to how these results translate to the more complex present day genetic testing environment and the patient and provider expectations of primary care in the USA.

In contrast, PCPs themselves identify some barriers to the provision of genetics services in routine practice. These include lack of confidence in genetics knowledge (Christensen et al. 2016; Houwink et al. 2011); limited time or focus on effective family history taking (Rich et al. 2004); and ethical and legal uncertainties about genetic testing (Houwink et al. 2011). A number of strategies to educate PCPs about genetics and facilitate incorporation of genetics services have been developed (Horowitz et al. 2015; Korf et al. 2014; Saul 2013; Zazove et al. 2015), but none has been widely implemented.

We sought to elucidate the perspectives of contemporary US patients and PCPs on the role of genetics in primary care. We surveyed 100 patients and conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with 20 of them. Additionally, we surveyed 26 and interviewed 10 of their PCPs in one major academic medical center.

Methods

Sample

Patients and PCPs responded to an online survey and completed semi-structured interviews to assess their perspectives through a mixed-methods approach. The online survey was emailed to 1169 primary care patients age 18 years or older, and to 36 PCPs within the same clinical practice setting. Consent forms and survey measures were administered through Qualtrics between May and September 2015. All survey participants could volunteer for interviews. A member of the research team contacted participants by email to schedule telephone interviews. The University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all interview participants provided oral consent before the start of their interview. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. An interdisciplinary team of individuals with backgrounds in primary care, clinical genetics and genetic counseling, genetic laboratory testing, and qualitative research developed and pilot tested surveys and semi-structured interview guides.

Measure and data collection

The patient survey (Supplementary information 1 online) assessed patient experience with and expectations of PCPs regarding genetic testing. Questions drew from previously published studies (Henneman et al. 2006; Kaphingst et al. 2012; Morren et al. 2007) and covered topics such as discussion of family history with PCP, experience with genetic testing, expectations of genetic testing in primary care, genetic literacy (adapted from the Genetic Literacy and Comprehension measure (Hooker et al. 2014), and numeracy (Schwartz et al. 1997).

A maximum variation sampling was used to select a diverse group of patients for interviews to ensure that we had a demographically representative sample of interviewees (Miles et al. 2013). Preference was given to recruit patients who previously had genetic testing, were younger than age 60, and males, as these groups were underrepresented in the available participant pool. We compensated patients with $20 gift cards for their participation in the interview. A single interviewer (LP) conducted semi-structured interviews lasting 27–83 min (μ = 43 min). Questions focused on the patients’ health status, family history, relationship with PCP, genetic testing experience, and expectations of future genetic testing (Supplementary information 2 online).

The PCP survey (Supplementary information 3 online) assessed demographics, genetics training, patient-expressed interest in genetic and genomic tests, and ordering patterns for such testing. For PCP interviews, a criterion sampling strategy was used to select purposefully PCPs with ≥ 50% time spent in clinics. A single interviewer (AN) conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with PCPs lasting 25–59 min (μ = 33 min). Questions focused on PCPs’ perceptions of genetic and genomic testing, barriers to testing in primary care, interest in learning about genetic testing, and support needed to implement genetic testing in a primary care setting.

Data analysis

Survey data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software, version 23. Patient surveys were assessed for statistically significant differences between participant responses based on demographic factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Patient survey | Patient interviews | Stanford Research Registrya | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (n) | (n) | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 61% | (57/93) | 65% | (7/20) | 59% | (1857/3149) |

| Mean age | 54.8 years | range 19–85 years | 58.6 years | range 24–82 years | 51.0 years | range 11–98 years |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 3% | (3/91) | 0% | (0/19) | 10% | (296/3005) |

| Non-Hispanic | 91% | (83/91) | 100% | (19/19) | 84% | (2525/3005) |

| Other, unknown or decline to answer | 5% | (5/91) | 0% | (0/19) | 6% | (184/3005) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 83% | (76/92) | 89% | (17/19) | 64% | (1617/2511) |

| Asian | 13% | (12/92) | 11% | (2/19) | 12% | (297/2511) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2% | (2/92) | 0% | (0/19) | 0.6% | (14/2511) |

| Black or African American | 1% | (1/92) | 0% | (0/19) | 3% | (85/2511) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1% | (1/92) | 0% | (0/19) | 0.1% | (2/2511) |

| Other, unknown, or decline to answer | 2% | (2/92) | 0% | (0/19) | 20% | (496/2511) |

| Education | ||||||

| 4-year college graduate or higher | 80% | (74/93) | 89% | (17/19) | 65% | (447/688) |

| Median household income | $100,000–$199,999 | $100,000–$199,999 | ||||

| Has children | 62% | (58/93) | 70% | (14/20) | 21% | (138/669) |

| Genetic literacy | ||||||

| 8/8 correct multiple choice questions | 74% | (72/97) | 70% | (14/20) | ||

| Mean score of word familiarity | 6.1/7 | 6.4/7 | ||||

| Numeracy mean score | 2.4/3 | 2.4/3 | ||||

| Genetics mean knowledge | 6.6 ± 3.6/12 | range (−5) to 12 |

||||

aThese demographics do not include Registry members who are not Stanford patients since they did not take the intake survey

Patient and PCP interview transcripts were analyzed using a process of inductive and deductive coding using matrices (Miles et al. 2013) and thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). A primary coder (LP, AN) reviewed and summarized all transcripts into a matrix based on the domains of the interview guide. A secondary coder (KO, EL) conducted an independent analysis of 30 and 50% of the transcripts, respectively. Each pair of coders compared the coding summaries and discussed discrepancies to reach consensus (Saldana 2015). We conducted a thematic analysis on completed matrices by reviewing each column for similarities, differences, and repetitions (Braun and Clarke 2006). We also compared themes from the patient and PCP data. Lastly, as part of our mixed-methods design, we performed data triangulation by comparing the survey results and interview themes to identify similarities and differences.

Results

Patient responses

One hundred thirty-three patients responded to the patient survey, 100 of whom met inclusion criteria (primary care patients age 18 years or older). Patients were primarily White, non-Hispanic, female, well-educated, and had children (Table 1). The subset of 20 patients who completed interviews was demographically similar to the survey respondent group. Genetic literacy and numeracy among participants were notably high. Four main themes emerged from the mixed-method analysis. Table 2 contains exemplary quotations for each theme described below.

Table 2.

Comparison of patient/PCP interview results

| Patient perspective | Primary care physician perspective | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Value of genetic testing | |||

| Patients believe genetic testing is generally beneficial | “You get this test and it tells you everything about your risks and your genetic makeup. So, I just think it could be interesting to know, you know, just again to help me keep healthy for the future. One of my goals is to live to a hundred. So, you know why not do this and be able to live a good life as long as possible?” | PCPs are uncertain about the clinical utility of genetic testing | “The problem right now is that we don’t know what to do with that information. We don’t know—like, if it’s a do you have 40% chance that you’ll develop this cancer in your lifetime. What do we do with that information?” “I’m very leery of things that don’t have hardcore evidence to improve outcomes. Especially because we’re doing such a miserable job in primary care.” |

| Concerns about genetic testing | |||

| Patients are concerned about the high cost of genetic testing | “It’s so new and probably really expensive I’m assuming. I’m guessing that insurance probably wouldn’t cover it.” | PCPs are concerned genetic testing may harm patients | “We need to educate the patients. What does genetic testing mean? Because a lot of people they think this can be a diagnostic disease problem. And again, that makes a lot of anxiety and frustration for people. I mean think about [if] I have a patient that has a risk factor for dementia/Alzheimer and I do genetic test and I say, ‘Oh, well you have a risk factor of a genetic. That you may have Alzheimer but I have no treatment for you.’ That kind of thing we should be careful about how we offer the genetic test. I mean what’s the goal of this, offering the genetic test?” |

| Patients believe genetic testing may cause harm to other people | “Somebody with very serious illnesses, and then they’re worried about whether their insurance will cover them because they find this out, or, anything like that, that makes it really hard for people.” | ||

| PCP role in genetic testing | |||

| Patients expect their PCPs to discuss genetic testing and offer referrals to genetic specialists | “And if she were to see something I would number one: I would expect she would be smart enough to see it if it were there; and two: she would mention it. And I’d be certainly willing and interested to talk with her about it.” “I would be open of course, but if no one brings it up I just let it go. Why should I, you know?” |

PCPs have limited knowledge about genetic testing and are cautious about their role in offering genetic testing. | “My concern is that we need to have a basic level of knowledge and competency to guide ordering of testing. Some of the obstacles or barriers would be that we don’t have systems to support routine genetic counseling in primary care yet.” “I will learn what I need to know as it becomes more established as a field and as it becomes evident that I need to know it.” |

Patients believe genetic testing is beneficial

Overall, patients had positive views of clinical genetic testing. Patients cited the potential to predict future health issues as the primary benefit of genetic testing. Most thought genetic testing could provide medically actionable information, such as making a diagnosis, taking steps to prevent a condition, or choosing the appropriate treatment. Some patients brought up additional benefits of genetic testing, such as satisfying curiosity, contributing to research, learning about ancestry, and helping family members. A few had ordered Direct to Consumer (DTC) genetic testing and brought it to their PCP to incorporate into their medical care. However, other participants thought DTC testing was different from testing ordered by a healthcare provider and wanted more information about its completeness or accuracy. Whether or not they believed the test provided medically actionable information, patients who had DTC testing expressed positive views about the experience. Over 80% of patients surveyed agreed with all of the favorable statements regarding genetic testing, which was consistent with patient interviews.

Patients are concerned about the high cost of genetic testing

The cost of genetic testing was a major theme for patients, both on a personal level and with regard to its impact on the healthcare system overall. During the interviews, patients expressed concern that their insurance company would not cover testing and that it would be very expensive to pay out of pocket. For some, this was the only barrier to having genetic testing. Furthermore, the majority of patients surveyed reported that cost was a barrier, and indicated that if a genetic test cost more than $500 out of pocket they would be less likely (37%, n = 34) or significantly less likely (26%, n = 24) to consider it.

Patients believe genetic testing may cause harm to other people

Patients brought up several concerns about genetic testing that were not personal for them, but might be for others. These issues included anxiety about results, difficulty understanding probability/risk numbers, data privacy, and insurance discrimination. A majority of patients surveyed (57%) indicated the use of genetic tests could lead to discrimination (Fig. 1), but 88% of patients reported they would want to know about their risk of severe disease and inform family members (Table 3). Although patients recognized the potential concerns about genetic testing, most would still want it.

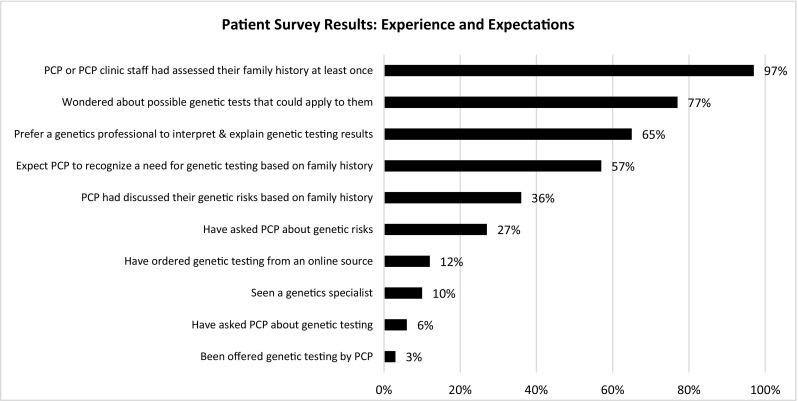

Fig. 1.

Patient experience and expectations

Table 3.

Patient attitudes toward genetic testing in primary care

| Disagree or strongly disagree | Neutral | Agree or strongly agree | ||||

| % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | |

| The use of genetic tests could lead to discriminationa | 19.4% | 18 | 23.7% | 22 | 57.0% | 53 |

| As long as a disease cannot be treated, I don’t want a genetic test for itb | 68.8% | 64 | 17.2% | 16 | 14.0% | 13 |

| Knowing my risk of getting a serious disease, I would be able to control my life morea | 3.2% | 3 | 15.1% | 14 | 81.7% | 76 |

| To prevent disease I would want to know my risk of getting certain diseasesa | 4.3% | 4 | 7.5% | 7 | 88.2% | 82 |

| I would inform my family about the results of a genetic test for a specific diseaseb | 3.2% | 3 | 8.6% | 8 | 88.2% | 82 |

| I think that the development of genetic testing is a positive medical progressb | 0.0% | 0 | 6.5% | 6 | 93.5% | 87 |

| Not confident/ not comfortable |

Neutral | Confident/comfortable | ||||

| % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | |

| How confident are you in your PCP’s awareness of genetic testing? | 5.5% | 5 | 38.5% | 35 | 56.0% | 51 |

| How confident are you in your PCP’s knowledge of genetics? | 6.5% | 6 | 36.6% | 34 | 57.0% | 53 |

| How comfortable are you asking about or discussing genetics with your PCP? | 4.3% | 4 | 10.8% | 10 | 84.9% | 79 |

Patients expect their PCPs to discuss genetic testing and offer referrals to genetic specialists

In both surveys and interviews, patients were confident in their PCP’s knowledge and awareness of genetics and comfortable discussing genetics with their PCP (Table 3). In interviews, most patients said they would prefer to have their PCP explain genetic test results to them and that they assumed their PCP was comfortable with genetics but had never discussed it with them. In contrast, when selecting from a list of healthcare providers, 65% of survey respondents preferred a genetics professional, such as a geneticist or genetic counselor, as the provider who should interpret and explain genetic testing (vs. 21% who chose their PCP). However, the majority (57%) still indicated that they would expect their PCP to be the first to recognize a need for genetic testing based on family history. In both interviews and surveys, patients reported that PCPs or clinic staff collected family history information but seldom used the information to discuss genetic risks.

PCP responses

The 26 primary care physicians surveyed were primarily White, non-Hispanic, and female (Table 4). The majority had not received any genetics training in the past year, and 54% had not ordered any genetic tests in the past 6 months. Many PCPs had patients bring genetic test results to their appointments and patients have asked nearly all PCPs about genetic testing. Ten of these primary care providers participated in surveys and semi-structured, telephone interviews. Eighty percent of the PCPs interviewed did not undergo genetic training and half of them ordered genetic testing at least once in the past 6 months. Table 2 provides exemplary quotations, from providers who participated in the telephone interviews, for each of the following three themes.

Table 4.

Primary care provider survey results

| Demographic data | Physician survey N = 26 |

Physicians interviewed N = 10 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 34.6 | 50.0 |

| Female | 65.4 | 50.0 |

| Agea | ||

| Mean | 45.88 ± 9.6 | 47.22 ± 10.8 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 3.8 | 90.0 |

| Non-Hispanic | 96.1 | 10.0 |

| Race | ||

| White | 57.7 | 50.0 |

| Asian | 34.6 | 30.0 |

| Black or African American | 3.9 | 10.0 |

| Other | 3.9 | 0 |

| Medical specialty | ||

| General Internal Medicine | 50 | 30.0 |

| Family Medicine | 46.2 | 50.0 |

| Missing | 3.8 | 0 |

| Years of practice | ||

| 1–9 | 34.6 | 30.0 |

| 10–19 | 26.9 | 30.0 |

| 20–29 | 30.8 | 30.0 |

| More than 30 | 3.8 | 10.0 |

| Time spent in clinic | ||

| > 50% | 65.4 | 70.0 |

| < =50% | 23 | 30.0 |

| Missing | 11.5 | 0 |

| Within the past year, have you had any genetic training or genetic/education (e.g., CME)? | ||

| Yes | 15.4 | 20.0 |

| No | 84.6 | 80.0 |

| In the past 6 months, how many times have your patients asked you about genetic testing? | ||

| None | 7.7 | 20.0 |

| 1–10 | 57.7 | 50.0 |

| 11–20 | 30.8 | 0 |

| More than 20 | 3.8 | 0 |

| In the past 6 months, how many times have you ordered genetic testing (single gene test, carrier) | ||

| None | 53.8 | 50.0 |

| 1–10 | 46.2 | 50.0 |

| 11–20 | 0 | 0 |

| More than 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Have your patients come to you with genetic test results that you didn’t order? | ||

| Yes | 73.0 | 80.0 |

| No | 26.9 | 20.0 |

aData in percentage unless stated otherwise

PCPs are uncertain about the clinical utility of genetic testing

PCPs conveyed uncertainty about the clinical utility of genetic testing in primary care. For example, although some PCPs expressed interest in using pharmacogenomics to improve decision-making about medications, most were unsure how relative risk information from genetic testing would alter treatment approaches in the primary care setting. Similarly, PCPs were often not aware or convinced of the evidence to support the use of genetic testing in primary care.

PCPs are concerned genetic testing may harm patients

PCPs emphasized how genetic testing could harm patients by resulting in anxiety and frustration, discrimination and reduced insurability, unequal access to testing, and financial burden. PCPs stressed that patients might not anticipate the negative implications of genetic testing; especially in instances when a test result was positive but treatment was not available, or when there was uncertainty about if or when a disease would manifest. PCPs also expressed concern regarding the potential for breaches in privacy and insurance discrimination. Lastly, PCPs described genetic tests as expensive, which could lead to unequal access to testing across different patient populations, and reported limited knowledge regarding insurance coverage and cost of testing to patients. Some were concerned that genetic tests might not be a wise use of healthcare dollars.

PCPs have limited knowledge about genetic testing and are cautious about their role in offering genetic testing

PCPs explained that they had limited training/preparation about which types of genetic tests to order, how to interpret results, and how to discuss genetic testing and test results with patients. Consequently, PCPs did not want to risk misinforming patients. PCPs were cautious about their role in providing genetic testing to patients beyond well-known genetic tests (e.g., BRCA, prenatal testing). PCPs described themselves as being “gatekeepers” to genetic testing but did not feel confident or interested in having a central role in genetic testing. They preferred to refer to genetics specialists to provide testing and counseling. Their disinterest or lack of confidence was partly due to already having to maintain the broad skill set needed to manage diverse conditions in a primary care setting. However, PCPs were open to enhancing their working knowledge of genetic testing, collaborating with genetics professionals, and learning about the clinical application of advancements in genetic medicine.

PCPs have recommendations for integrating genetic testing into primary care

PCPs offered suggestions on how to address the three themes described above. Some PCPs recommended waiting to incorporate genetic testing into primary care until the implications for patient management were clearly established. Others recommended research on the best way to integrate genetic testing into primary care. To address potential harms to patients, PCPs suggested having open and transparent discussions with patients about the factors described above (e.g., inconclusive results, patient anxiety). Finally, PCPs consistently recommended more genetics education targeted at PCPs, guidance on interpreting results, and clarification around their role as “gatekeepers” to specialized genetic testing and counseling.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first mixed-methods study comparing patient and PCP attitudes toward incorporating genetics into primary care practice. Patients and PCPs agree that PCPs are the “gatekeepers” to genetics services and see value in referring to or meeting with genetics specialists. Both groups also identify concerns about the high cost of testing to individuals and the healthcare system, as well as concerns about the potential for insurance discrimination. There is a disconnect, however, between patients’ and PCPs’ perceptions of the value of genetic testing in primary care and their expectations of PCPs’ role in the provision of genetics services. This is clearly demonstrated in patients’ expectation that PCPs will review the results of genetic testing that they did not recommend or order, such as DTC testing, and incorporate this information into clinical care. These gaps may adversely affect the provider-patient relationship and in some cases may have an adverse impact on patient care.

Our data is consistent with previous research, showing patients have positive attitudes toward genetic testing as a useful healthcare tool (Fitzgerald-Butt et al. 2014; Haga et al. 2013; Hall et al. 2014). PCPs acknowledge that genetic testing is or can become a valuable tool in healthcare (Haga et al. 2012) but require more evidence that incorporating it into primary care will improve patient outcomes (Vassy et al. 2015). Also, several surveys of PCPs note gaps in knowledge and lack of clear and consistent guidelines and professional education geared toward PCPs (Acton et al. 2000; Chambers et al. 2015; Klitzman et al. 2013).

PCPs were more concerned than patients in this study about the potential harms of genetic testing. While genetic testing, like many medical tests, may raise patients’ anxiety levels in the short term, most patients return to baseline anxiety levels within 6 months of testing (Bloss et al. 2011; Bloss et al. 2013). PCPs and patient concerns about insurance discrimination are also rarely borne out. The federal Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) has protected patients from health insurance and employment discrimination based on genetic status since 2008. Following GINA, documented cases of genetic discrimination have been very limited (Feldman 2012; Green et al. 2015). PCPs worry about unequal access to genetic testing, a concern which is not unique to genetic services. However, costs are decreasing over time, and insurance companies are establishing criteria for coverage, particularly when consensus testing and management guidelines exist.

Perhaps the most difficult divide to bridge is between the genetics services that patients expect of their PCPs and what PCPs feel capable of delivering. Patients believe their PCP is evaluating their family history for genetic risks and will bring up the topic or refer if warranted. However, PCPs do not feel they have the time or training to take a detailed family history and evaluate risk (Mainous et al. 2013; Rich et al. 2004). Even with clear evidence-based guidelines such as US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guideline for BRCA testing or the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) guideline for Lynch Syndrome (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2005), many PCPs do not make appropriate genetics referrals (Wood et al. 2013). Patients assume that when physicians do not discuss genetic risk or testing, those genetic services are unwarranted. However, providers may simply not have the resources to assess family history or referral pathways adequately in place for genetic counseling when indicated.

Frameworks and recommendations have been developed for integrating genetics into the practice of medicine across disciplines, including primary care (EGAPP Working Group 2016; Korf et al. 2014). The Institute of Medicine Genomics Roundtable proposed potential solutions using clinical implementation science (David et al. 2015). PCPs have suggested some interventions that could facilitate their use of appropriate genetic testing. These include genetics training with additional links to information that they could use as needed, prompts in the electronic medical record to have an additional discussion of family history, and alerts for PCPs when relevant genetic test results are available. Clinical decision support systems to facilitate incorporation of genetics services in primary care have been developed, but none has been widely implemented (Horowitz et al. 2015; Scheuner et al. 2014; Zazove et al. 2015).

All technological innovations require providers to learn new information if they are to incorporate it into their existing practice. Other specialties, such as obstetrics and oncology, have begun to integrate genetic testing and appropriate referrals into daily practice. The benefits of doing so in primary care are not yet as clearly demonstrated, but there are many opportunities and, as pointed out by PCPs, potential pitfalls to navigate. Genetics professionals should continue to work with primary care physicians and their patients to incorporate appropriate genetic services and to bridge the gap between their expectations and practice.

Limitations

This study offers a preliminary look at the gap between patient and PCP expectations of genetic testing in primary care. However, it is important to note that the sample size is small, lacks racial/ethnic diversity, and many potential participants did not respond to survey and interview requests. The low proportion of African American, Asian, and Hispanic/Latino participants in the survey and interviews is similar to the proportion of these groups in the larger Stanford Research Registry (Table 1) and reflects both challenges to recruiting minority participants for genetics research and the demographics of the mid-peninsula region of the Bay Area. Research participants at this major academic medical center in Silicon Valley may also be more enthusiastic about new technologies than patients at other institutions. Further research is needed to understand the current spectrum of patient and PCP opinions on this topic in the USA.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 90 kb)

(PDF 65 kb)

(PDF 27 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Division of Primary Care and Population Health (PCPH) of Stanford University School of Medicine for providing access to the Stanford Research Registry and providing funds to patient survey respondents to allocate to a PCPH research topic of their choice. This work was supported by Stanford Health Care and the Stanford Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) to Spectrum (UL1 TR001085). The CTSA program is led by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Stanford Health Care or the NIH. Lastly, we would like to acknowledge Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment (STRIDE), a research and development project at Stanford University which creates a standards-based informatics platform supporting clinical and translational research.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was supported by Stanford Health Care and the Stanford Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) to Spectrum (UL1 TR001085). Ethics approval was obtained from the University’s Institutional Review Board, whose identification was deliberately omitted to protect patients’ identities.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Conflict of interest

Lauren Puryear, Natalie Downs, Andrea Nevedal, Eleanor T. Lewis, Kelly E. Ormond, Maria Bregendahl, Carlos J. Suarez, Sean P. David, Steven Charlap, Isabella Chu, Steven M. Asch, Neda Pakdaman, Sang-ick Chang, Mark R. Cullen, and Latha Palaniappan declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Lauren Puryear and Natalie Downs indicate equal contribution.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12687-017-0349-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Acton RT, Burst NM, Casebeer L, Ferguson SM, Greene P, Laird BL, Leviton L. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of Alabama’s primary care physicians regarding cancer genetics. Acad Med. 2000;75(8):850–852. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200008000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss CS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Effect of direct-to-consumer genomewide profiling to assess disease risk. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):524–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss CS, Wineinger NE, Darst BF, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Impact of direct-to-consumer genomic testing at long term follow-up. J Med Genet. 2013;50(6):393–400. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(May 2015):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) Lynch Syndrome EGAPP recommendation

- Chambers C, Axell-house D, Mills G, Bittner-Fagan H, Rosenthal M, Johnson M, Stello B. Primary care physicians’ experience and confidence with genetic testing and perceived barriers to genomic medicine. J Fam Med. 2015;2(2):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen KD, Vassy JL, Jamal L, Lehmann LS, Slashinski MJ, Perry DL, et al. Are physicians prepared for whole genome sequencing? A qualitative analysis. Clin Genet. 2016;89(2):228–234. doi: 10.1111/cge.12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SP, Johnson SG, Berger AC, Feero WG, Terry SF, Green LA, Phillips RL, Ginsburg GS. Making personalized health care even more personalized: insights from activities of the IOM genomics roundtable. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(4):373–380. doi: 10.1370/afm.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ST, Mafi JN, Landon BE. Trends and quality of care in outpatient visits to generalist and specialist physicians delivering primary care in the United States, 1997-2010. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):947–955. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2808-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGAPP Working Group (2016) EGAPP Working Group Recommendations. Retrieved March 22, 2016, from http://www.egappreviews.org/recommendations/index.htm

- Emery J, Kumar S, Smith H. Patient understanding of genetic principles and their expectations of genetic services within the NHS: a qualitative study. Community Genet. 1998;1(2):78–83. doi: 10.1159/000016141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman EA. The genetic information nondiscrimination act (GINA): public policy and medical practice in the age of personalized medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(6):743–746. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-1988-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald-Butt SM, Klima J, Kelleher K, Chisolm D, McBride KL. Genetic knowledge and attitudes of parents of children with congenital heart defects. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(12):3069–3075. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RC, Lautenbach D, McGuire AL. GINA, genetic discrimination, and genomic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):397–399. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1404776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga S, Burke W, Ginsburg G, Mills R, Agans R. Primary care physicians’ knowledge of and experience with pharmacogenetic testing. Clin Genet. 2012;82(4):388–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga SB, Barry WT, Mills R, Ginsburg GS, Svetkey L, Sullivan J, Willard HF. Public knowledge of and attitudes toward genetics and genetic testing. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013;17(4):327–335. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MJ, Forman AD, Montgomery SV, Rainey KL, Daly MB (2014) Understanding patient and provider perceptions and expectations of genomic medicine. J Surg Oncol (April 2014), 9–17. doi:10.1002/jso.23712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hamburg MA, Collins FS. The path to personalized medicine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(4):301–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneman L, Timmermans DRM, Van Der Wal G. Public attitudes toward genetic testing: perceived benefits and objections. Genet Test. 2006;10(2):139–145. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.10.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker GW, Peay H, Erby L, Bayless T, Biesecker BB, Roter DL. Genetic literacy and patient perceptions of IBD testing utility and disease control: a randomized vignette study of genetic testing. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(5):901–908. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz CR, Abul-Husn NS, Ellis S, Ramos MA, Negron R, Suprun M, Zinberg RE, Sabin T, Hauser D, Calman N, Bagiella E, Bottinger EP. Determining the effects and challenges of incorporating genetic testing into primary care management of hypertensive patients with African ancestry. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;47:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houwink EJ, van Luijk SJ, Henneman L, van der Vleuten C, Jan Dinant G, Cornel MC. Genetic educational needs and the role of genetics in primary care: a focus group study with multiple perspectives. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(5):9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaphingst KA, Facio FM, Cheng M-R, Brooks S, Eidem H, Linn A, Biesecker BB, Biesecker LG. Effects of informed consent for individual genome sequencing on relevant knowledge. Clin Genet. 2012;82(5):408–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman R, Chung W, Marder K, Shanmugham A, Chin LJ, Stark M, Leu CS, Appelbaum PS. Attitudes and practices among internists concerning genetic testing. J Genet Couns. 2013;22(1):90–100. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9504-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf BR, Berry AB, Limson M, Marian AJ, Murray MF, O’Rourke PP, Passamani ER, Relling MV, Tooker J, Tsongalis GJ, Rodriguez LL. Framework for development of physician competencies in genomic medicine: report of the Competencies Working Group of the Inter-Society Coordinating Committee for Physician Education in Genomics. Genet Med. 2014;16(11):1–6. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainous AG, Johnson SP, Chirina S, Baker R. Academic family physicians’ perception of genetic testing and integration into practice: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2013;45(4):257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 3. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Morren M, Rijken M, Baanders AN, Bensing J. Perceived genetic knowledge, attitudes towards genetic testing, and the relationship between these among patients with a chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitceathly RDS. Mitochondrial extrapyramidal syndromes: using age and phenomenology to guide genetic testing. JAMA Neurol. 2016;1(6):5–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich EC, Burke W, Heaton CJ, Haga S, Pinsky L, Short MP, Acheson L. Reconsidering the family history in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J (2015) Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd Edition. (J. Seaman, Ed.). SAGE Publications

- Saul RA. Genetic and genomic literacy in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2013;132(Suppl 3):S198–S202. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1032C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner MT, Hamilton AB, Peredo J, Sale TJ, Austin C, Gilman SC, Bowen MS, Goldzweig CL, Lee M, Mittman BS, Yano EM. A cancer genetics toolkit improves access to genetic services through documentation and use of the family history by primary-care clinicians. Genet Med. 2014;16(1):60–69. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Black WC, Welch HG. The role of numeracy in understanding the benefit of screening mammography. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(11):966–972. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-11-199712010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung N. Management of women with BRCA mutations: a 41-year-old woman with a BRCA mutation and a recent history of breast cancer. JAMA. 2011;305(21):2211–2220. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(5):355–361. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-5-200509060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassy JL, Lautenbach DM, McLaughlin HM, Kong SW, Christensen KD, Krier J, et al. The MedSeq project: a randomized trial of integrating whole genome sequencing into clinical medicine. Trials. 2014;15(85):85. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassy JL, Christensen KD, Slahinski MJ, Lautenbach DM, Raghavan S, Robinson JO, et al. Someday it will be the norm’: physician perspectives on the utility of genome sequencing for patient care in the MedSeq Project. Personalized Med. 2015;12(1):23–32. doi: 10.2217/pme.14.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf MJ, Noeth D, Rammohan C, Shah SH. Complexities of genetic testing in familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2016;9(1):95–99. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood ME, Flynn BS, Stockdale A. Primary care physician management, referral, and relations with specialists concerning patients at risk for cancer due to family history. Public Health Genomics. 2013;16(3):75–82. doi: 10.1159/000343790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazove P, Plegue MA, Uhlmann WR, Ruffin MT. Prompting primary care providers about increased patient risk as a result of family history: does it work? J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(3):334–342. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.03.140149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 90 kb)

(PDF 65 kb)

(PDF 27 kb)