Abstract

Trichophyton rubrum and T. violaceum are prevalent agents of human dermatophyte infections, the former being found on glabrous skin and nail, while the latter is confined to the scalp. The two species are phenotypically different but are highly similar phylogenetically. The taxonomy of dermatophytes is currently being reconsidered on the basis of molecular phylogeny. Molecular species definitions do not always coincide with existing concepts which are guided by ecological and clinical principles. In this article, we aim to bring phylogenetic and ecological data together in an attempt to develop new species concepts for anthropophilic dermatophytes. Focus is on the T. rubrum complex with analysis of rDNA ITS supplemented with LSU, TUB2, TEF3 and ribosomal protein L10 gene sequences. In order to explore genomic differences between T. rubrum and T. violaceum, one representative for both species was whole genome sequenced. Draft sequences were compared with currently available dermatophyte genomes. Potential virulence factors of adhesins and secreted proteases were predicted and compared phylogenetically. General phylogeny showed clear gaps between geophilic species of Arthroderma, but multilocus distances between species were often very small in the derived anthropophilic and zoophilic genus Trichophyton. Significant genome conservation between T. rubrum and T. violaceum was observed, with a high similarity at the nucleic acid level of 99.38 % identity. Trichophyton violaceum contains more paralogs than T. rubrum. About 30 adhesion genes were predicted among dermatophytes. Seventeen adhesins were common between T. rubrum and T. violaceum, while four were specific for the former and eight for the latter. Phylogenetic analysis of secreted proteases reveals considerable expansion and conservation among the analyzed species. Multilocus phylogeny and genome comparison of T. rubrum and T. violaceum underlined their close affinity. The possibility that they represent a single species exhibiting different phenotypes due to different localizations on the human body is discussed.

Key words: Adhesion, Arthrodermataceae, Character analysis, Dermatophytes, Genome, Phylogeny, Protease, Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton violaceum

Introduction

Dermatophytes (Onygenales: Arthrodermataceae) are filamentous fungi that invade and grow in keratin-rich substrates. Many species of this family reside as saprobes in the environment or as commensals in animal fur, but particularly among the anthropophiles there are species that are able to invade hairless human skin and nails and cause infection. About 10 dermatophyte species commonly occur on the human host, and it is estimated that about 20–25 % of the world's population carries a dermatophyte infection (Ates et al., 2008, Kim et al., 2015). Nearly 80 % of these are caused by Trichophyton rubrum and its close relatives (Havlickova et al. 2008). The genus Trichophyton in the modern sense contains 16 species, of which seven are anthropophilic (de Hoog et al. 2017), among which are T. rubrum and T. violaceum.

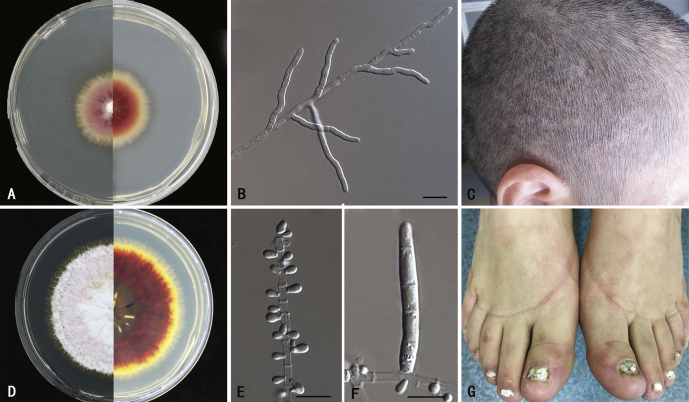

Trichophyton rubrum and T. violaceum share some significant ecological traits. Both are anthropophilic, i.e. restricted to the human host, causing chronic, non- or mild-inflammatory infections. Their high degree of molecular similarity is expressed in widely used barcoding genes, e.g. rDNA Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS), translation elongation factor 1 and partial β-tubulin (Gräser et al., 2000, Rezaei-Matehkolaei et al., 2014, Mirhendi et al., 2015). However, the species show significant phenotypic and clinical differences. Trichophyton rubrum typically presents as fluffy to woolly, pinkish colonies with moderate growth speed, while T. violaceum appears as wrinkled, deep purple colonies with slow growth. Microscopically T. rubrum has a profusely branched and richly sporulating conidial system with tear-shaped micro- and cigar-shaped macroconidia. In contrast, hyphae of T. violaceum are broad, tortuous and distorted, without sporulation and with chlamydospore-like conidia in older cultures. These morphological differences coincide with marked clinical differences. Trichophyton rubrum usually causes infections of glabrous skin leading to tinea corporis, tinea pedis, tinea manuum or onychomycosis (Ates et al. 2008). Trichophyton violaceum usually infects hair and adjacent skin of the scalp, leading to black dot tinea capitis (Farina et al., 2015, Gräser et al., 2000; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypes of two anthropophilic dermatophytes. A–C.Trichophyton violaceum, CBS 141829. A. colony on SGA, 3 wk, 27 °C, obverse and reverse. B. non-sporulating hyphae. C. clinical image of the isolate (tinea capitis). D–G.Trichophyton rubrum, CBS 139224. D. colony on SGA, 3 wk, 27 °C, obverse and reverse. E. microconidia. F. macroconidia. G. clinical image of the isolate (onychomycosis). Scale bar = 10 μm.

The molecular basis of the pathogenicity-associated traits among dermatophytes is currently insufficiently understood to explain the striking differences between the clinical predilections of Trichophyton rubrum and T. violaceum (Gräser et al. 2000). In 2011, the first genomes of dermatophyte species became available; 97 % of the 22.5 Mb genome of Trichophyton benhamiae and T. verrucosum were completed and aligned (Burmester et al. 2011). Shortly afterwards five further genomes of important dermatophytes, T. rubrum, T. tonsurans, T. equinum, Microsporum canis and Nannizzia gypsea were added (Martinez et al. 2012). This enabled a comparative analysis of gene families that might be responsible for specific types of pathogenesis, such as proteases, kinases, secondary metabolites and proteins with LysM binding domains. The above species account for the majority of tinea infections; however, the main agent of tinea capitis, T. violaceum was not included. To further understand the genetics of T. rubrum siblings and their divergent pathomechanisms, we sequenced the genomes of two clinical strains T. rubrum CMCC(F)T1i (=CBS 139224) and T. violaceum CMCC(F)T3l (=CBS 141829) from South China using Illumina HiSeq®2000 platform. To obtain optimal quality of the reference sequence, PacBio RS single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing was also applied to the strain of T. rubrum, besides the Illumina methods. Very high genome quality was yielded for both isolates. The draft sequences from our strains were compared with each other and with seven dermatophyte genomes available in the public domain, with a focus on proteases and adhesins. The study allowed us to explore genomic polymorphism in dermatophytes and its implications for pathogenesis and adaptation, aiming to lead to better understanding of genome organization and evolution of specific pathogenic traits.

Materials and methods

Strains and culture conditions

Strains preserved in the reference collection of Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (housed at Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute) were used to construct a multilocus phylogeny of the family Arthrodermataceae. In total, 264 strains were included, of which 261 were from CBS and 3 from BCCM/IHEM Biomedical Fungi and Yeasts Collection, Brussels, Belgium (Table 1). Strains were cultured on Sabouraud's Glucose Agar (SGA) plates inoculated by lyophilized, cryo-preserved or fresh mycelial material. Most of the cultures were grown for 7–14 d at 24 °C. Two strains used for whole-genome sequencing were grown in Sabouraud's glucose broth (SGB); see below.

Table 1.

Strains information in phylogeny study.

| CBS number | Current taxon name | New taxon name | Status | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBS 221.75 | A. borellii | A. borellii | Rat | |

| CBS 967.68 | A. borellii | A. borellii | ST Nannizzia borellii | Bat |

| CBS 272.66 | C. georgiae | A. ciferrii | T Arthroderma ciferrii | Soil |

| CBS 492.71 | A. cuniculi | A. cuniculi | ST Arthroderma cuniculi | Rabbit burrow |

| CBS 495.71 | A. cuniculi | A. cuniculi | ST Arthroderma cuniculi | Rabbit burrow |

| CBS 353.66 | A. curreyi | A. curreyi | ET Arthroderma curreyi | Soil |

| CBS 117155 | T. eboreum | A. eboreum | T Trichophyton eboreum | Skin |

| CBS 292.93 | T. sp. | A. eboreum | Skin | |

| CBS 473.78 | A. flavescens | A. flavescens | ST Arthroderma flavescens | Kingfisher |

| CBS 474.78 | A. flavescens | A. flavescens | ||

| CBS 598.66 | A. gertleri | A. gertleri | ST Trichophyton vanbreuseghemii | Soil |

| CBS 666.77 | A. gertleri | A. gertleri | ||

| CBS 228.79 | A. gloriae | A. gloriae | T Arthroderma gloriae | Soil |

| CBS 663.77 | A. gloriae | A. gloriae | ||

| CBS 664.77 | A. gloriae | A. gloriae | ||

| CBS 521.71 | A. insingulare | A. insingulare | Soil | |

| CBS 522.71 | A. insingulare | A. insingulare | Soil | |

| CBS 307.65 | A. lenticulare | A. lenticulare | T Arthroderma lenticulare | Gopher burrow |

| CBS 308.65 | A. lenticulare | A. lenticulare | T Arthroderma lenticulare | Gopher burrow |

| CBS 120.30 | T. tonsurans | A. melis | Human | |

| CBS 669.80 | A. melis | A. melis | T Arthroderma melis | Badger burrow |

| CBS 419.71 | A. multifidum | A. multifidum | ST Arthroderma multifidum | Rabbit burrow |

| CBS 420.71 | A. multifidum | A. multifidum | ST Arthroderma multifidum | Rabbit burrow |

| CBS 132920 | T. sp. | A. onychocola | T Trichophyton onychocola | Human |

| CBS 364.66 | T. phaseoliforme | A. phaseoliforme | ST Trichophyton phaseoliforme | Mountain rat |

| CBS 117.61 | A. quadrifidum | A. quadrifidum | AUT Arthroderma quadrifidum | Soil |

| CBS 118.61 | A. quadrifidum | A. quadrifidum | AUT Arthroderma quadrifidum | Soil |

| CBS 138.26 | A. curreyi | A. quadrifidum | ||

| CBS 310.65 | A. quadrifidum | A. quadrifidum | Soil | |

| CBS 311.65 | A. quadrifidum | A. quadrifidum | Soil | |

| CBS 134551 | T. redellii | A. redellii | T Trichophyton redellii | Bat |

| CBS 132929 | T. thuringiense | A. sp. | Nail | |

| CBS 417.71 | T. thuringiense | A. thuringiense | T Trichophyton thuringiense | Mouse |

| CBS 473.77 | A. tuberculatum | A. tuberculatum | T Arthroderma tuberculatum | Blackbird |

| CBS 101515 | A. uncinatum | A. uncinatum | T Keratinomyces ajelloi | Soil |

| CBS 119779 | T. ajelloi var. ajelloi | A. uncinatum | Nail | |

| CBS 128.75 | A. uncinatum | A. uncinatum | ST E. stockdaleae | Soil |

| CBS 179.57 | A. uncinatum | A. uncinatum | Soil | |

| CBS 180.57 | A. uncinatum | A. uncinatum | Soil | |

| CBS 180.64 | A. uncinatum | A. uncinatum | ST Keratinomyces ajelloi var. nanum | Soil |

| CBS 315.65 | A. uncinatum | A. uncinatum | ST Arthroderma uncinatum | Soil |

| CBS 316.65 | A. uncinatum | A. uncinatum | ST Arthroderma uncinatum | Soil |

| CBS 355.93 | C. vespertilii | A. vespertilii | T Chrysosporium vespertilium | Bat intestine |

| CBS 187.61 | Ctenomyces serratus | Ctenomyces serratus | NT Ctenomyces serratus | Soil |

| CBS 544.63 | Ctenomyces serratus | Ctenomyces serratus | Soil | |

| CBS 100148 | A. uncinatum | E. floccosum | Skin | |

| CBS 108.67 | E. floccosum var. floccosum | E. floccosum | Human | |

| CBS 230.76 | E. floccosum var. floccosum | E. floccosum | NT Epidermophyton floccosum | Human |

| CBS 240.67 | E. floccosum var. floccosum | E. floccosum | Skin | |

| CBS 457.65 | E. floccosum var. nigricans | E. floccosum | ||

| CBS 553.84 | E. floccosum var. floccosum | E. floccosum | Human | |

| CBS 269.89 | Keratinomyces ceretanicus | Guarromyces ceretanicus | ||

| CBS 100083 | A. grubyi | L. gallinae | ||

| CBS 243.66 | A. grubyi | L. gallinae | T Nannizzia grubyi | Dog |

| CBS 244.66 | A. grubyi | L. gallinae | Scalp | |

| CBS 300.52 | A. grubyi | L. gallinae | NT Lophopyton gallinae | |

| CBS 545.93 | M. audouinii | M. audouinii | NT Microsporum audouinii | Scalp |

| CBS 495.86 | A. otae | M. audouinii | T Nannizzia otae | |

| CBS 102894 | M. audouinii | M. audouinii | Scalp | |

| CBS 108932 | M. audouinii | M. audouinii | ||

| CBS 108933 | M. audouinii | M. audouinii | Human | |

| CBS 108934 | M. audouinii | M. audouinii | Human | |

| CBS 119449 | M. audouinii | M. audouinii | Scalp | |

| CBS 404.61 | M. audouinii | M. audouinii | AUT Sabouraudites langeronii | Human |

| CBS 101514 | A. otae | M. canis | T Microsporum distortum | Scalp |

| CBS 114329 | M. canis | M. canis | Skin | |

| CBS 130922 | M. canis | M. canis | Skin | |

| CBS 130931 | M. canis | M. canis | Skin | |

| CBS 130932 | M. canis | M. canis | Skin | |

| CBS 130949 | M. canis | M. canis | Human | |

| CBS 156.69 | A. otae | M. canis | Skin | |

| CBS 191.57 | A. otae | M. canis | Dog | |

| CBS 214.79 | A. otae | M. canis | Rabbit | |

| CBS 217.69 | A. otae | M. canis | Nail | |

| CBS 238.67 | A. otae | M. canis | Human | |

| CBS 274.62 | A. otae | M. canis | Monkey | |

| CBS 281.63 | A. otae | M. canis | Scalp | |

| CBS 283.63 | A. otae | M. canis | ||

| CBS 284.63 | A. otae | M. canis | Gibbon | |

| CBS 445.51 | M. ferrugineum | M. canis | ||

| CBS 482.76 | A. otae | M. canis | Skin | |

| CBS 496.86 | A. otae | M. canis | ST Nannizzia otae, NT Microsporum canis | Cat |

| CBS 109478 | M. audouinii | M. canis | Scalp | |

| CBS 317.31 | M. ferrugineum | M. ferrugineum | ||

| CBS 373.71 | M. ferrugineum | M. ferrugineum | Human | |

| CBS 449.61 | M. ferrugineum | M. ferrugineum | ||

| CBS 452.59 | T. concentricum | M. ferrugineum | Skin | |

| CBS 497.48 | M. ferrugineum | M. ferrugineum | Scalp | |

| CBS 366.81 | A. corniculatum | N. corniculata | ST Nannizzia corniculata | Soil |

| CBS 364.81 | A. corniculatum | N. corniculata | ST Nannizzia corniculata | Soil |

| CBS 349.49 | M. duboisii | N. duboisii | T Sabouraudites duboisii | Skin |

| CBS 599.66 | A. fulvum | N. fulva | T Microsporum boullardii | Soil |

| CBS 130934 | M. fulvum | N. fulva | Soil | |

| CBS 130942 | M. fulvum | N. fulva | Human | |

| CBS 146.66 | M. gypseum | N. fulva | AUT Favomicrosporon pinettii | Contaminant |

| CBS 147.66 | M. gypseum | N. fulva | AUT Favomicrosporon pinettii | Contaminant |

| CBS 243.64 | A. fulvum | N. fulva | T Keratinomyces longifusus | Scalp |

| CBS 287.55 | A. fulvum | N. fulva | T Microsporum fulvum | Human |

| CBS 385.64 | A. otae | N. fulva | Human | |

| CBS 529.71 | A. fulvum | N. fulva | T Microsporum ripariae | Birdnest |

| CBS 120675 | M. gypseum | N. gypsea | ||

| CBS 100.64 | M. gypseum var. vinosum | N. gypsea | ST Microsporum gypseum var. vinosum | Skin |

| CBS 118893 | M. gypseum | N. gypsea | Skin | |

| CBS 130936 | M. gypseum | N. gypsea | Skin | |

| CBS 130939 | M. gypseum | N. gypsea | Skin | |

| CBS 171.64 | A. gypseum | N. gypsea | Soil | |

| CBS 258.61 | A. gypseum | N. gypsea | NT Gymnoascus gypseus | Soil |

| CBS 130948 | M. gypseum | N. incurvata | Skin | |

| CBS 173.64 | A. incurvatum | N. incurvata | Skin | |

| CBS 174.64 | A. incurvatum | N. incurvata | T Nannizzia incurvata | Skin |

| CBS 314.54 | A. obtusum | N. nana | T Microsporum gypseum var. nanum | Scalp |

| CBS 321.61 | A. obtusum | N. nana | ST Nannizzia obtusa | Human |

| CBS 322.61 | A. obtusum | N. nana | ST Nannizzia obtusa | Human |

| CBS 632.82 | A. obtusum | N. nana | Human | |

| CBS 421.74 | A. persicolor | N. persicolor | ||

| CBS 871.70 | A. persicolor | N. persicolor | ST Nannizzia quinckeana | Skin |

| CBS 288.55 | M. praecox | N. praecox | AUT Microsporum praecox | Human |

| CBS 128066 | M. praecox | N. praecox | Skin, from horse | |

| CBS 128067 | M. praecox | N. praecox | Skin, from horse | |

| CBS 121947 | M. amazonicum | N. sp. | Skin | |

| CBS 450.65 | A. racemosum | N. sp. | T Microsporum racemosum | Rat |

| CBS 130935 | M. racemosum | P. cookei | Soil | |

| CBS 227.58 | A. cajetanum | P. cookei | ||

| CBS 228.58 | A. cajetanum | P. cookei | T Microsporum cookei | Soil |

| CBS 337.74 | A. cajetanum | P. cookei | Soil | |

| CBS 423.74 | A. racemosum | P. cookei | ST Nannizzia racemosa | Soil |

| CBS 424.74 | A. racemosum | P. cookei | ST Nannizzia racemosa | Soil |

| CBS 101.83 | A. cookiellum | P. cookiellum | ST Nannizzia cookiella | Soil |

| CBS 102.83 | A. cookiellum | P. cookiellum | ST Nannizzia cookiella | Soil |

| CBS 124422 | M. mirabile | P. mirabile | ST Microsporum mirabile | Chamois |

| CBS 129179 | M. mirabile | P. mirabile | ST Microsporum mirabile | Nail |

| CBS 646.73 | A. vanbreuseghemii | T. vanbreuseghemii | T Arthroderma vanbreuseghemii | |

| CBS 809.72 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | ||

| CBS 112368 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | Skin, from guinea pig | |

| CBS 112369 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | Skin, from guinea pig | |

| CBS 112370 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | Skin, from guinea pig | |

| CBS 112371 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | Skin, from guinea pig | |

| CBS 112857 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | Skin, from guinea pig | |

| CBS 112859 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | Skin, from rabbit | |

| CBS 120669 | T. mentagrophytes | T. benhamiae | Guinea pig | |

| CBS 280.83 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | Skin | |

| CBS 623.66 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | ST Arthroderma benhamiae | Human |

| CBS 624.66 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | ST Arthroderma benhamiae | |

| CBS 806.72 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | Guinea pig | |

| CBS 934.73 | A. benhamiae | T. benhamiae | ||

| CBS 131645 | T. bullosum | T. bullosum | Skin | |

| CBS 363.35 | T. bullosum | T. bullosum | T Trichophyton bullosum | Horse |

| CBS 557.50 | T. bullosum | T. bullosum | ||

| CBS 196.26 | T. concentricum | T. concentricum | NT Trichophyton concentricum | Skin |

| CBS 448.61 | T. concentricum | T. concentricum | Skin | |

| CBS 563.83 | T. concentricum | T. concentricum | Skin | |

| CBS 109036 | T. equinum | T. equinum | Skin | |

| CBS 100080 | T. equinum | T. equinum | T Trichophyton equinum var. autotrophicum | Horse |

| CBS 270.66 | T. equinum | T. equinum | NT Trichophyton equinum | Horse |

| CBS 285.30 | T. tonsurans | T. equinum | T Trichophyton areolatum | |

| CBS 634.82 | T. equinum | T. equinum | Horse | |

| CBS 344.79 | T. erinacei | T. erinacei | Skin | |

| CBS 474.76 | T. erinacei | T. erinacei | T Trichophyton proliferans | Skin |

| CBS 511.73 | T. erinacei | T. erinacei | T Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. erinacei | Hedghog |

| CBS 124411 | T. sp. | T. erinacei | Dog | |

| CBS 220.25 | T. eriotrephon | T. eriotrephon | T Trichophyton eriotrephon | Skin |

| CBS 108.91 | T. erinacei | T. interdigitale | ||

| CBS 110.65 | T. mentagrophytes | T. interdigitale | Groin | |

| CBS 113880 | T. mentagrophytes | T. interdigitale | Nail | |

| CBS 117723 | A. vanbreuseghemii | T. interdigitale | Skin | |

| CBS 119447 | T. violaceum | T. interdigitale | Scalp | |

| CBS 232.76 | A. vanbreuseghemii | T. interdigitale | Skin | |

| CBS 425.63 | A. vanbreuseghemii | T. interdigitale | T Trichophyton batonrougei | |

| CBS 428.63 | A. vanbreuseghemii | T. interdigitale | NT Trichophyton interdigitale | Skin |

| CBS 449.74 | A. vanbreuseghemii | T. interdigitale | Skin | |

| CBS 475.93 | A. vanbreuseghemii | T. interdigitale | T Trichophyton krajdenii | Skin |

| CBS 559.66 | A. vanbreuseghemii | T. interdigitale | Skin | |

| CBS 647.73 | A. vanbreuseghemii | T. interdigitale | T Trichophyton candelabrum | Nail |

| CBS 124426 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | Dog | |

| CBS 124410 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | Dog | |

| CBS 124419 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | ||

| CBS 124424 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | Chamois | |

| CBS 124425 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | Cat | |

| CBS 304.38 | T. radicosum | T. mentagrophytes | T Trichophyton radicosum | |

| IHEM 4268 | T. mentagrophytes | T. mentagrophytes | NT Trichophyton mentagrophytes | |

| CBS 126.34 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | T Bodinia abyssinica | Skin |

| CBS 120324 | T. mentagrophytes | T. mentagrophytes | Skin | |

| CBS 120356 | T. mentagrophytes | T. mentagrophytes | Scalp | |

| CBS 124401 | A. benhamiae | T. mentagrophytes | Guinea pig | |

| CBS 124404 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | Rabbit | |

| CBS 124408 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | Dog | |

| CBS 124415 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | Cat | |

| CBS 124421 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | Rabbit | |

| CBS 124420 | T. interdigitale | T. mentagrophytes | Rabbit | |

| CBS 120357 | T. mentagrophytes | T. mentagrophytes | Scalp | |

| CBS 158.66 | T. mentagrophytes | T. quinckeanum | Skin | |

| CBS 318.56 | T. mentagrophytes | T. quinckeanum | NOT NT Microsporum mentagrophytes | Skin |

| IHEM 13697 | T. quinckeanum | T. quinckeanum | NT Trichophyton quickeanum | Mouse |

| CBS 100081 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | T Trichophyton fischeri | Contaminant |

| CBS 100084 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | T Trichophyton raubitschekii | Skin |

| CBS 100238 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | ||

| CBS 102856 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Nail | |

| CBS 110399 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Skin | |

| CBS 115314 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Nail | |

| CBS 115315 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Skin | |

| CBS 115316 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Skin | |

| CBS 115317 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Human | |

| CBS 115318 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Nail | |

| CBS 117539 | T. rubrum var. flavum | T. rubrum | Nail | |

| CBS 118892 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Nail | |

| CBS 289.86 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | T Trichophyton kanei | Skin |

| CBS 376.49 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | T Trichophyton rodhainii | Skin |

| CBS 392.58 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | NT Epidermophyton rubrum | Skin |

| CBS 592.68 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | T Trichophyton fluviomuniense | Skin |

| CBS 120425 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Nail | |

| CBS 202.88 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Skin | |

| CBS 288.86 | T. rubrum | T. rubrum | Contaminant | |

| CBS 118537 | T. schoenleinii | T. schoenleinii | Scalp | |

| CBS 118538 | T. schoenleinii | T. schoenleinii | Scalp | |

| CBS 118539 | T. schoenleinii | T. schoenleinii | Scalp | |

| CBS 433.63 | T. schoenleinii | T. schoenleinii | Scalp | |

| CBS 458.59 | T. schoenleinii | T. schoenleinii | NT Trichophyton schoenleinii | Human |

| CBS 417.65 | A. simii | T. simii | Poultry | |

| CBS 448.65 | A. simii | T. simii | ST Arthroderma simii | Poultry |

| CBS 449.65 | A. simii | T. simii | ST Arthroderma simii | Poultry |

| CBS 520.75 | A. simii | T. simii | Macaca | |

| CBS 109033 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Horse | |

| CBS 109034 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Horse | |

| CBS 112186 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Human | |

| CBS 112187 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Human | |

| CBS 112188 | T. equinum | T. tonsurans | Horse | |

| CBS 112189 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Human | |

| CBS 112190 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Horse | |

| CBS 112191 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Human | |

| CBS 112192 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Horse | |

| CBS 112193 | T. equinum | T. tonsurans | Horse | |

| CBS 112194 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Horse | |

| CBS 112195 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Horse | |

| CBS 112198 | T. equinum | T. tonsurans | Human | |

| CBS 112856 | A. benhamiae | T. tonsurans | Scalp, zoo transmission | |

| CBS 182.76 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | Horse | |

| CBS 318.31 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | T Trichophyton floriforme | |

| CBS 338.37 | T. immergens | T. tonsurans | T Trichophyton immergens | Skin |

| CBS 496.48 | T. tonsurans | T. tonsurans | NT Trichophyton tonsurans | Scalp |

| CBS 130944 | T. verrucosum | T. verrucosum | Scalp | |

| CBS 130945 | T. verrucosum | T. verrucosum | Skin | |

| CBS 130946 | T. verrucosum | T. verrucosum | Scalp | |

| CBS 130947 | T. verrucosum | T. verrucosum | Skin | |

| CBS 134.66 | T. verrucosum | T. verrucosum | Scalp | |

| CBS 161.66 | T. verrucosum | T. verrucosum | Skin | |

| CBS 282.82 | T. verrucosum | T. verrucosum | Cow | |

| CBS 326.82 | T. verrucosum | T. verrucosum | Cow | |

| CBS 365.53 | T. verrucosum | T. verrucosum | NT Trichophyton verrucosum | Cow |

| CBS 517.63 | T. rubrum | T. violaceum | T Trichophyton kuryangei | Scalp |

| CBS 452.61 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | Scalp | |

| CBS 118535 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | Scalp | |

| CBS 119446 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | Scalp | |

| CBS 120316 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | Scalp | |

| CBS 120317 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | Scalp | |

| CBS 120318 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | Scalp | |

| CBS 120319 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | Scalp | |

| CBS 120320 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | Scalp | |

| CBS 178.91 | T. sp. | T. violaceum | Nail | |

| CBS 201.88 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | Skin | |

| CBS 118548 | M. ferrugineum | T. violaceum | Scalp | |

| CBS 305.60 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | T Trichophyton yaoundei | Scalp |

| CBS 359.62 | T. balcaneum | T. violaceum | T Trichophyton balcaneum | Human |

| CBS 374.92 | T. violaceum | T. violaceum | NT Trichophyton violaceum | Skin |

| IHEM 19751 | T. soudanense | T. violaceum | NT Trichophyton soudanense | Scalp |

A = Arthroderma; C = Chrysosporium; E = Epidermophyton; M = Microsporum; N = Nannizzia; L = Lophophyton; P = Paraphyton; AUT = authentic; ET = epitype; NT = neotype; ST = syntype; T = (ex-)holotype

DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing

DNA extraction for phylogeny was performed using MasterPure™ Yeast DNA Purification Kit from Epicentre, using preserved material or material harvested from living cultures using methods and PCR protocols of Stielow et al. (2015) and de Hoog et al. (2017). In total eight gene regions were amplified: ITS and LSU loci of the rDNA operon, partial β-tubulin II (TUB2), γ-actin (ACT), translation elongation factor 1-α (TEF1), RNA polymerase II (rPB2), 60S ribosomal protein L10 (RP 60S L1) and two primer sets for the fungal-specific translation elongation factor 3 (TEF3). The chosen loci, corresponding primer sets, primer sequences, PCR volumes and PCR reactions are given by Stielow et al. (2015). After visualization of amplicons on 1 % agarose, positive products were sequenced using ABI big dye terminator v. 3.1, with one quarter of its suggested volume (modified manufacturer's protocol). Bidirectional sequencing was performed using a capillary electrophoresis system (Life Technologies 3730XL DNA analyser). Obtained sequences of CBS strains were manually edited and stored in a Biolomics database at Westerdijk Institute (Vu et al. 2012). Consensus sequences of IHEM strains were edited using SeqMan in the Lasergene 219 software (DNAStar, WI, U.S.A.).

Alignment, phylogeny and locus assessment

A subset of 123 strains was firstly tested with nine sets of primers for eight DNA loci. In the second analysis, 141 strains were added for which five chosen loci were analyzed. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using tools provided at http://www.phylogeny.fr/ with and without Gblocks to eliminate poorly aligned positions and divergent regions because of the large phylogenetic distance and high divergence of studied taxa. In the T. rubrum complex, all known ex-type/ neotype strains of synonymized species were included. In total, 134 strains were successfully amplified.

Obtained sequences were aligned with Mafft v. 8.850b using default settings, except for the ‘genafpair’ option (Katoh et al. 2009). The nine alignments obtained from the initial dataset of 123 strains were subjected to phylogenetic analysis using maximum likelihood (ML) in Mega v. 8.0 software. In the second analysis of the total dataset of with 264 strains, Raxml analysis v. 8.0.0 employing gtrcat model and 1 000 bootstrap replicates and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm with MrBayes v. 3.2.6 in the Cipres portal (https://www.phylo.org/) were performed.

Multilocus analysis of T. rubrum complex

A total of 44 strains were amplified for five genes: ITS with primers ITS4 and ITS5, the D1-D2 region of LSU with primers LR0R and LR5, partial b-tubulin (TUB2) with primers TUB2Fd and TUB4Fd, 60S ribosomal protein L10 with 60S-908R and 60-S506F and translation elongation factor 3 (TEF3) with primers EF3-3188F and EF3-3984R (Stielow et al. 2015). Sequences were aligned with web alignment tool Mafft. ITS phylogeny tree was reconstructed by Mega v. 6.06 using Maximum likelihood with Tamura-Nei model and 500 bootstrap replications with Trichophyton benhamiae as outgroup. The remaining genes were explored with SNP analysis because of their high degrees of conservation.

Strains and DNA extraction for genome sequencing

Strains used were fresh isolates from cases of onychomycosis (CBS 139224 = CMCC(F)T1i = T. rubrum) and tinea capitis (CBS 141829 = CMCC(F)T3l = T. violaceum) of patients in Nanchang, China. Strains were identified as T. rubrum and T. violaceum on the basis of both phenotypic characters and sequencing (ITS and partial β-tubulin). Cultures were grown in Sabouraud's glucose broth (SGB) incubated at 27 °C for 7–20 d. Cells were harvested during late log phase by centrifugation at 6 000 g for 30 min. Genomic DNA was extracted using the EZNA Fungal DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Doraville, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified DNA was quantified by TBS-380 fluorometer (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). High quality DNA (OD260/280 = 1.8–2.0 > 10 μg) was used for further research.

Library construction and sequencing

For Illumina sequencing, at least 2 μg genomic DNA was used for each strain for library construction. Paired-end libraries with insert sizes of ∼300 bp were constructed according to the manufacturer's instructions (AIR™ Paired-End DNA Sequencing Kit, BioScientific, Beijing, China). Sequencing was done using Illumina HiSeq2000 technology with PE100 or PE125 mode. Raw sequencing data was generated by Illumina base calling software Casava v. 1.8.2 (http://support.illumina.com/sequencing/sequencing_software/casava.ilmn). Contamination reads, such as ones containing adaptors or primers were identified by SeqPrep (https://github.com/jstjohn/SeqPrep) with parameters: “-q 20 -L 25 -B AGATCGGAAGAGCGTCGTGT-A AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTC”. Sickle (https://github.com/najoshi/sickle) was applied to conduct reads data trimming with default parameters to get clean data in this study. Clean data obtained by above quality control processes were used to do further analysis.

For PacBio RS (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) sequencing, 8–10 k insert whole genome shotgun libraries were generated and sequenced using standard protocols. An aliquot of 10 μg DNA was spun in a Covaris g-TUBE (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA) at 3 500 g for 60 s using an Eppendorf 5 424 centrifuge (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY, U.S.A.). DNA fragments were purified, end-repaired and ligated with SMRTbell™ sequencing adapters following manufacturer's recommendations (Pacific Biosciences). Resulting sequencing libraries were purified three times using 0.45 × vols of Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's recommendations. PacBio RS sequencing work was performed with C2 reagents.

Genome assembly and annotation

The T. rubrum CBS 139224 genome was sequenced using a combination of PacBio RS and Illumina sequencing platforms. The T. violaceum CBS 141829 was sequenced by Illumina only. Data were used to evaluate the complexity of the genome and assembled using Velvet (v. 1.2.09) with a k-mer length of 17. Contigs with lengths of less than 200 bp were discarded to increase reliability. The assembly was first produced using a hybrid de novo assembly solution modified by Koren et al. (2012), in which a de-Bruijn based assembly algorithm and a CLR reads correction algorithm were integrated in a PacBio To CA with Celera assembler pipeline. The final assembled genome was verified manually.

The protein coding genes (CDS) were predicted with a combination of three gene prediction methods, GeneMark-ES v. 2.3a (Ter-Hovhannisyan et al. 2008), Augustus v. 2.5.5 (Stanke & Morgenstern 2015) and Snap (http://korflab.ucdavis.edu/software.html) prediction. The resulting predictions were integrated using Glean (Elsik et al. 2007).

Open-reading frames with less than 300 base pairs were discarded. The remaining ORFs were queried against non-redundant database (nr in NCBI), SwissProt (http://uniprot.org), KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), and EggNOG (http://eggnogdb.embl.de/#/app/home) in view of functional annotation (BlastX cutoff: e-value < 1e−5).

Repetitive elements and microsatellites

The assembled genomes of T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829 were searched for repetitive elements by RepBase (http://www.girinst.org/server/RepBase/index.php) (Bao et al. 2015). and RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org/) using the eukaryotic repeat database. A Perl-based script Matfinder v. 2.0.9 was used for microsatellite identification from assembled scaffolds. The mononucleotide repeats were ignored by modifying the configuration file. The repeat thresholds for di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexa-nucleotide motifs were set as 8, 5, 5, 5 and 5, respectively. Microsatellite sequences with flanking sequences longer than 50 bp at both sides were collected for future marker development.

Adhesin prediction

Gene families were determined using OrthoMCL v. 2.0.3 (Inflation value = 1.5, E-value < 1e−5) and domains were annotated for each orthologous cluster using InterProScan software (http://www.ebi.ac.uk) with default parameters. On the basis of previous reports of fungal adhesin prediction, six software products were tested, viz. FungalRV (Chaudhuri et al. 2011), SignalP 4.0 (de Groot et al., 2013, Teixeira et al., 2014), PredGPIpredictor (http://gpcr2.biocomp.unibo.it/predgpi/pred.htm), FaaPred (Ramana & Gupta 2010), big-PIPredictor (Teixeira et al. 2014) and TMHMM (de Groot et al., 2013, Teixeira et al., 2014). Overall results were evaluated to provide best combinations.

Mitochondrial genome assembly and annotation

The mitochondrial genomes of T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829 were assembled from the Illumina reads using GRAbB (https://github.com/b-brankovics/grabb; Brankovics et al. 2016). The mitochondrial genome sequence of T. rubrum BMU 01672 (GenBank acc. Nr. FJ385026) was used as a reference for the GRAbB assembly. The final assembly was done using SPAdes 3.8.1 (Bankevich et al. 2012), which resulted in the assembly of a single circular contig in both cases.

The initial mitochondrial genome annotations were done using MFannot (http://megasun.bch.umontreal.ca/) and were manually curated. Annotation of tRNA genes was improved using tRNAscan-SE (Pavesi et al. 1994), annotation of intron-exon boundaries was improved by comparing to available reference sequences. Intron encoded proteins were identified using NCBI's ORF Finder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) and annotated using InterPro (Mitchell et al. 2015) and CD-Search (Marchler-Bauer & Bryant 2004).

Phylogeny of proteases

Whole genome sequences (nucleotide and amino acid levels) of the nine dermatophytes (T. rubrum CBS 118892, T. tonsurans CBS 112818, Nannizzia gypsea CBS 118893, Microsporum canis CBS 113480, T. equinum CBS 127.97, T. benhamiae CBS 112371, T. verrucosum HKI0517) were set as a local database in CLC genomics bench 7.0. Reference protease sequences within the protease families of subtilisins (S8A family), fungalysins (M36 family) and deuterolysins (M35 family) were loaded from Uniprot database (http://www.uniprot.org/) and homologous sequences were searched in a dermatophyte comparative database (https://olive.broadinstitute.org/projects/Dermatophyte%20Comparative). Orthologs were selected when E-values were less than 10−10 and similarities were higher than 90 % at nucleotide level. Mega v. 6.0 was used to construct the phylogenetic tree. The robustness of the phylogenetic trees calculated by NJ, and the ML approach was estimated by bootstrap analyses with 500 replications using maximum likelihood and Bayesian techniques. The trees were modified in Adobe Photoshop CS5.

Secondary metabolite biosynthesis

Analysis with the antibiotic and Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell (antiSmash; Weber et al. 2015) predicted several potential secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters.

Results

ITS phylogeny of dermatophytes

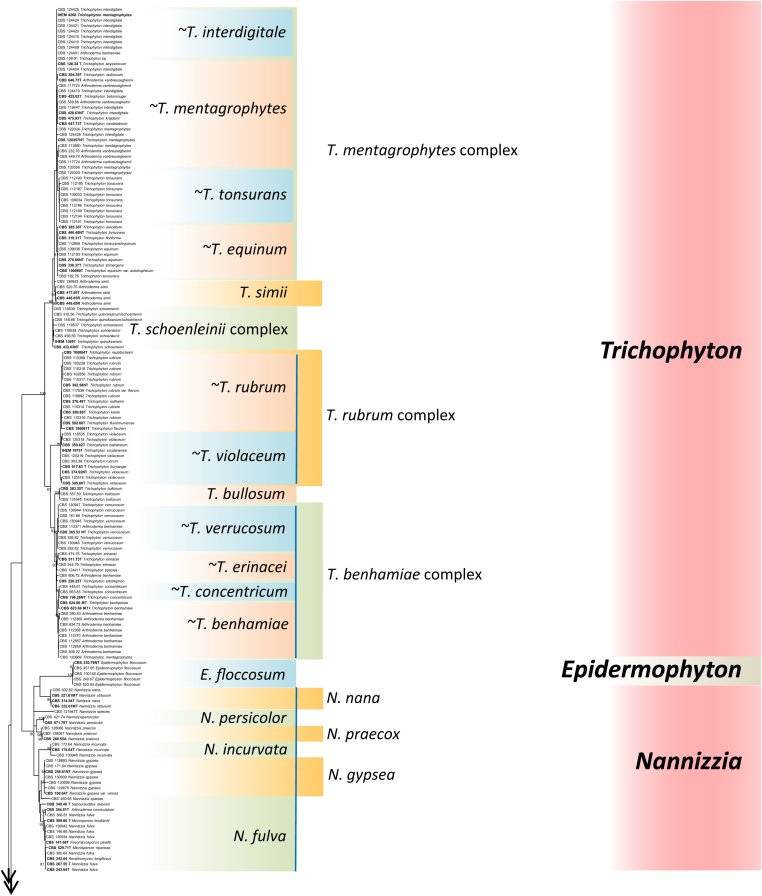

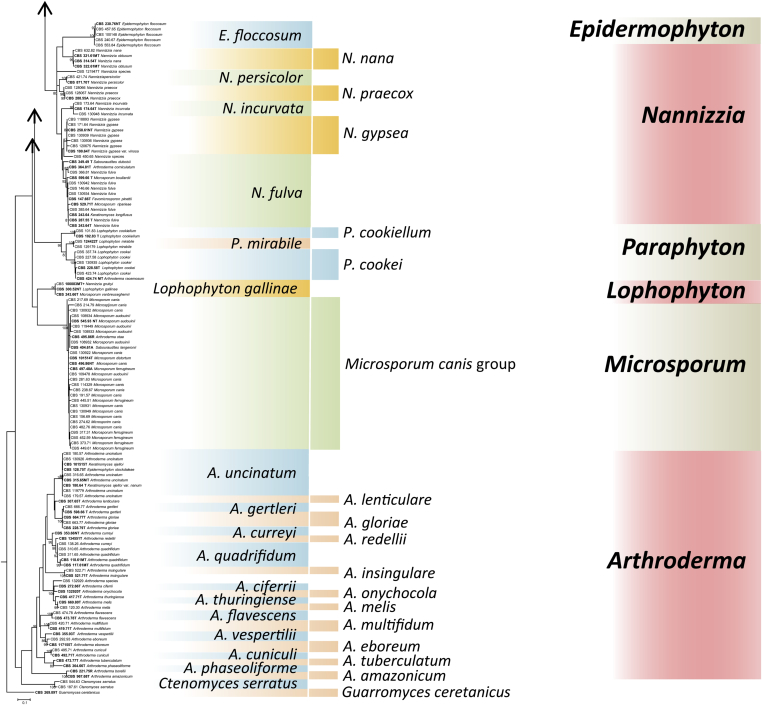

Obtained rDNA ITS sequences were used to construct a taxonomic overview of Arthrodermataceae allowing comparison of relative distances between species when ITS is used as barcoding marker. Guarromyces ceretanicus was used as outgroup in the tree constructed with Maximum likelihood using RAxML v. 8.0.0 under gtrcat model and 1000 bootstrap replications (Fig. 2). Bootstrap support above 80 % is shown above branches. In addition to Guarromyces and Ctenomyces, seven bootstrap-supported clades can be observed which were interpreted by de Hoog et al. (2017; Clades A‒G) as genera: Arthroderma, Epidermophyton, Lophophyton. Microsporum, Nannizzia, Paraphyton, and Trichophyton. In this review, Arthroderma contains 21 currently accepted species and the ITS tree shows 16 bootstrap-supported branches (76 %); similarly, the multi-species genera Microsporum (3 species), Nannizzia (9 species), Paraphyton (3 species) and Trichophyton (16 species) had a ratio of bootstrap-support of 0 %, 56 %, 100 % and 56 %, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of rDNA ITS of 264 dermatophyte strains, using RaxML v. 8.0.0 under gtrcat model and 1000 bootstrap replications. Bootstrap support above 80 % is shown above branches. Species complexes are indicated when ITS distinction of taxa was not unambiguous (marked with ∼). Guarromyces ceretanicus CBS 269.89 was used as outgroup. Abbreviations used: A = authentic, ET = epitype, NT = neotype, T = type; MT = mating type. Numbers in bold are authentic or reference for described taxa.

For an assessment of primer sets and resulting phylogenetic trees, we employed four parameters to select loci with superior identification and phylogenetic power and to exclude the ones with poor performance: (1) PCR robustness, (2) number of obtained amplicons, (3) total number of supported clades (BS > 80 %) in trees, and (4) monophyly of the genera. Based on these parameters, TUB2, RP 60S L1, and TEF3 were chosen for further analysis along with the standard ITS and LSU loci. From the total set of 264 strains five alignments were created of successfully amplified sequences, containing n = 238 (ITS), n = 219 (LSU), n = 198 (TUB2), n = 211 (TEF3) and n = 222 (RP 60S L1) sequences respectively (Table 2). The alignments were analyzed using Raxml v. 8.0.0 and MrBayes v. 3.2.6 analysis with additional Raxml v. 8.0.0 analysis (R147) on the five alignments containing 147 sequences from successfully amplified loci (Table 3). The highest number of supported clades (n = 40) was found in ITS three, followed by RP 60S L1 (n = 30), TUB2 (n = 29), and LSU (n = 17) and TEF3 (n = 17) (Table 2). Monophyly of seven ITS-defined genera (Arthroderma, Epidermophyton, Lophophyton, Microsporum, Nannizzia, Paraphyton, and Trichophyton) in Arthrodermataceae was taken as lead for attributing clades in the other genes using the three analyses mentioned above are displayed in (Fig. 3). ITS trees were stable, independent from size of data sets or used algorithm. In the largest comparisons, the more remote Guarromyces ceretanicus was selected as outgroup because of an unclear position of Ctenomyces serratus in these trees, but ITS topology was identical. Nannizzia was a supported clade in all three analyses, with lower bootstrap and posterior probability values. In none of the remaining trees, the genus Nannizzia was recognized as a monophyletic group. Poor resolution was achieved with TUB2 and RP 60S L1, while LSU and TEF3 had very poor performance as phylogenetic markers. Since the ITS produced by far the largest number of supported clades, taking another gene as reference would not yield trustworthy results. Therefore, datasets of ITS sequences were concluded to be superior compared to the other four loci, decomposing the entire tree in clades with BS > 80 %. In a final analysis, the TEF3 dataset was excluded. The tree of concatenated sequences of ITS, TUB2, RP 60S L1 and partial LSU had similar topology as ITS alone (de Hoog et al. 2017).

Table 2.

Robustness of phylogenetic trees for ITS LSU, TUB2, TEF3, RP 60S L1.

Number of amplicons per locus for the data set of 264 strains.

Number of clades with bootstrap value BS > 70 %, in phylogenetic trees obtained from 147 strains possessing all 5 amplicons.

Table 3.

Assessment of phylogenetic trees for ITS, LSU, TUB2, TEF3, and RP 60S L1 obtained by Maximum Likelihood in RAxML v8.0.0 and MrBayes v.3.2.6. Numbers represent bootstrap supports and posterior probabilities of the clades higher than 80% and 0.9 (BS > 80%, PP > 0.9) respectively, representing the genera.

| Locus |

ITS |

LSU |

TUB2 |

TEF3 |

RP 60S L1 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software | B238 | R147 | R238 | B219 | R147 | R219 | B198 | R147 | R198 | B211 | R147 | R211 | B222 | R147 | R222 |

| T | 1 | 100 | 100 | X | X | X | 1 | 99 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 98 | 100 |

| E | 1 | 100 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 94 |

| N | 0.98 | 85 | 84 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| P | 1 | 100 | 100 | 0.99 | X | 86 | 0.99 | 0 | 86 | X | X | 99 | 1 | 100 | X |

| M | 1 | 100 | 100 | 1 | 99 | 99 | 1 | 100 | 99 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 100 |

| A | 1 | 99 | 95 | 0 | X | 83 | 0.99 | 95 | 0 | X | X | X | X | 0 | 0 |

| L | 1 | ND | 100 | 0.97 | ND | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 | ND | 100 |

Abbreviations used: R = RAxML v8.0.0 software; B = MrBayes v.3.2.6 software; T = Trichophyton; E = Epidermophyton; N = Nannizzia; P = Paraphyton; M = Microsporum; A = Arthroderma; L = Lophophyton; ND = no data; X = no clade.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of five gene-trees based on maximum datasets of strains analyzed (ITS n = 238, LSU n = 219, TUB2 n = 198, TEF3 n = 211, RP-60S L1 n = 222), compared with a set of strains for which all genes were sequenced (n = 147). Phylogenetic analysis was done with RaxML, MrBayes, using Guarromyces ceretanicus or Ctenomyces serratus as outgroup. Bootstrap values > 80 % are shown with the branches.

Polymorphism of T. rubrum complex

Polymorphism of the T. rubrum complex was explored in 47 strains was analyzed in the T. rubrum (n = 30) and T. violaceum (n = 17) (Table S1). LSU, TUB2, RP 60S L1 and TEF3 were nearly invariable with only a few SNPs found (data not shown). TUB2 has two genotypes due to a single difference at position 106 (Fig. S1). In TEF3 three haplotypes were found, among which 38 (81 %) belonged to a single genotype 1. Four strains (T. violaceum CBS 730.88, T. rubrum CBS 110399, T. violaceum CBS 120319, T. violaceum CBS 120318) presented as genotype 2, with six 6 SNPs compared to genotype 1. Five strains (T. violaceum CBS 305.60, CBS 374.92, CBS 118535, CBS 120320, CBS 120317) presented as genotype 3 with a single SNP (Fig. S1). In LSU three genotypes were found (Fig. S1). RP 60S L1 comprised two genotypes, with nine strains of T. violaceum deviating from the prevalent type (Fig. S1). ITS showed limited variability (Fig. S2). A group including the neotype CBS 392.58 was nearly monomorphic, with T. violaceum separated by four SNPs. A group of strains from various African countries and with T. rubrum phenotypes shared characteristics with both main clusters. Strains of the T. rubrum cluster had 7 AT repeats at the end of ITS2 while T. violaceum mostly had 8‒14 and the African T. rubrum were variable in this character.

Trichophyton rubrum and T. violaceum genomes

For T. rubrum CBS 139224, 49.01 M (Pair-End Library) raw reads were generated by Hiseq2000 with PE100 mode. The Q30 value of raw reads was 91.74 % and Q30 of clean data was 95.53 %. In addition, 130473 PacBio subfilter reads (N50 = 2 867 bp) were obtained. A total of 762 contigs (N50 = 53 276 bp) were assembled and were joined to create 19 super-scaffolds (scaffold N50 of 2 198 313 bp) with the genome size 22.3 Mb. The overall G + C content of entire genome was 48.34 % and the ambiguous bases accounted for 0.055 %. Sequences without Ns that could not be extended at either end were generated to obtain 7 170 unigenes with an average length of 1 677 bp per gene. Coding-gene regions (CDS) accounted for 53.9 % of the genome. Consequently, the intergenic regions were 10 277 739 bp.

In T. violaceum CBS 141829, 28.72 M (Pair-End Library) and 21.55 M (Mate-Pair Library) raw reads were generated by Hiseq2000 with PE125 mode. The Q30 value of raw reads was above 90 % and Q30 of clean data was above 93 %. Subsequently 278 scaffolds (N50 = 1 335 347 bp) were obtained with a total length of 23 310 379 bp, among of which 77 scaffolds which were longer than 1 000 bp. The G + C content of the genome was 47.22 % with an N-rate of 0.476 %. In total 7 415 genes were predicted with 1,596 bp as average length. Raw data of the two genomes are summarized in Table 4 together with the previously sequenced T. rubrum strain CBS 118892.

Table 4.

Raw genome data of T. rubrum CBS 139224 and CBS 118892, T. violaceum CBS 141829.

| Index | CBS 139224 | CBS 118892 | CBS 141829 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated sites | China, nail | Germany, nail | China, Scalp |

| Isolated time | 2012 | 2004 | 2013 |

| Mating type | MAT1-1 | MAT1-1 | MAT1-1 |

| Scaffold number | 19 | 36 | 278 |

| Length of all scaffolds | 22 301 977 | 22 530 013 | 23 378 626 |

| G + C (%) | 48.344 % | 48.31 % | 47.22 % |

| Scaffolds N50 | 2 198 313bp | / | 1 335 347bp |

| No. of genes | 7 170 | 8 804 | 7 415 |

| N % | 0.055 % | / | 0.476 % |

| GC content in gene region (%) | 51.2 % | / | 51.0 % |

| Gene/Genome | 53.9 % | / | 50.6 % |

| Gene average length | 1 677 bp | 1 393bp | 1 595 bp |

| Intergenetic region length | 10 277 739bp | / | 11 549 290 bp |

| GC content in intergenetic region (%) | 44.9 % | / | 43.2 % |

| Intergenetic length/genome (%) | 46.1 % | 51.69 % | 49.4 % |

Comparing T. rubrum CBS 139224 vs. CBS 118892 (Fig. S2), the latter had a slightly larger genome size (22.5 Mb) with more scaffolds (35) compared to strain CBS 139224 of 22.3 Mb. The genomes were highly similar despite their different geographic origins, but CBS 139224 sequences joined more appropriately with longer scaffolds. At the nucleotide level, the strains revealed a 99.83 % similarity rate. For annotation, the reads were mapped against CBS genome sequences, and combined with ab initio gene prediction we annotated 7 170 genes in total in CBS 139224, compared with 7 415 genes in CBS 118892.

Our newly sequenced strains of T. rubrum vs. T. violaceum (CBS 139224 and CBS 141829) shared high colinearity at the nucleotide level, with 99.0 % identity (Fig. S3). Eighteen protein coding sequences were annotated, among of which two were specific for CBS 139224 and 16 for CBS 141829 by Interpro analysis. The eighteen genes were involved in ATP transferase activity, calcium ion binding and lipid transportation, in addition to four null interpret domains (Table 5). Since they cannot explain the observed differences in pathogenesis, we analyzed the sequence similarity among orthologs of these two strains. In total 6 708 orthologs were obtained, and 85 and 237 paralogs were discovered in CBS 139224 and CBS 141829, respectively. Table 6 lists 14 paralogs with variant duplications. Compared to T. rubrum CBS 139224, T. violaceum CBS 141829 appeared to have some paralogs with quite different function. For example, A7D00_1963 in T. rubrum and A7C99_6543 in T. violaceum code for a ribosome biogenesis protein BRX1, while the same ortholog of T. violaceum had two additional different domains, coding for a hypothetical protein (A7C99_6542) and an F-box protein (A7C99_6544). A7D00_2958 encodes a dipeptidylaminopeptidase, while it has two entirely different paralogs in T. violaceum (A7C99_207 and A7C99_208). These homologs with diverse evolution maybe related to dermatophyte tissue preference and specialization.

Table 5.

Specific domains for T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829 by interpro analysis. “Null”refers to absence of records in Interpro database.

| E-value | ACESSION | IPR-ID | Functional domain | Annotation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. rubrum CBS 139224 | 0 | A7D00_4483 | NULL | NULL | |

| T. rubrum CBS 139224 | 0 | A7D00_5801 | NULL | NULL | |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 5.30E-11 | A7C99_7410 | IPR022414 | ATP:guanidophosphotransferase, catalytic domain | transferase activity |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 3.70E-18 | A7C99_7399 | NULL | NULL | |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 1.20E-21 | A7C99_7396 | IPR010009 | Apolipophorin-III | lipid transport |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 2.20E-11 | A7C99_7390 | IPR011992 | EF-hand domain pair | calcium ion binding |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 1.50E-06 | A7C99_7408 | NULL | NULL | |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 4.70E-39 | A7C99_7391 | IPR022414 | ATP:guanidophosphotransferase catalytic domain | transferase activity |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 3.10E-20 | A7C99_7375 | IPR005204 | Hemocyanin, N-terminal | |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 1.10E-19 | A7C99_7415 | IPR022413 | ATP:guanidophosphotransferase, N-terminal | transferase activity |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 5.40E-39 | A7C99_7385 | IPR000896 | Hemocyanin/hexamerin middle domain | |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 2.80E-12 | A7C99_7394 | IPR011992 | EF-hand domain pair | calcium ion binding |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 1.10E-23 | A7C99_7376 | IPR005204 | Hemocyanin, N-terminal | |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 2.90E-102 | A7C99_7381 | IPR022414 | ATP:guanidophosphotransferase, catalytic domain | transferase activity |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 1.50E-65 | A7C99_7374 | IPR005203 | Hemocyanin, C-terminal | |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 8.20E-11 | A7C99_7395 | IPR011992 | EF-hand domain pair | calcium ion binding |

| T. violaceum CBS 141829 | 4.30E-36 | A7C99_7404 | IPR022413 | ATP:guanidophosphotransferase, N-terminal | transferase activity |

Table 6.

Notable different paralogs of T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829.

| TRCMCC | Probable function | TVCMCC | Probable function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthomcl-22 | A7D00_722 | NIMA-interacting protein TinC | A7C99_4561 A7C99_4562 A7C99_4563 A7C99_4564 |

NIMA-interacting protein TinC hypothetical protein hypothetical protein hypothetical protein |

| Orthomcl-33 | A7D00_1963 | Ribosome biogenesis protein BRX1 | A7C99_6542 A7C99_6543 A7C99_6544 |

hypothetical protein 60S ribosome biogenesis protein Brx1 F-box protein |

| Orthomcl-37 | A7D00_2627 | phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase, PIP5K | A7C99_6653 A7C99_6654 A7C99_6655 |

hypotheticalprotein CMGC/SRPK protein kinase Serine/threonine-protein kinase SKY1 |

| Orthomcl-39 | A7D00_2721 | Cell division protein Sep4a | A7C99_523 A7C99_524 A7C99_525 |

Mitochondrial carrier protein hypothetical protein vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein TDA6 |

| Orthomcl-43 | A7D00_2958 | dipeptidylaminopeptidase | A7C99_206 A7C99_207 A7C99_208 |

dipeptidylaminopeptidase succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit 26S protease regulatory subunit, putative; |

| Orthomcl-46 | A7D00_3180 | AAA family ATPase | A7C99_7 A7C99_8 A7C99_9 |

MFS drug transporter Protein cft1 AAA family ATPase |

| Orthomcl-50 | A7D00_3895 | ABC transporter | A7C99_2690 A7C99_2691 A7C99_2692 |

Aminotransferase ABC transporter hypothetical protein |

| Orthomcl-53 | A7D00_4340 | Succinate/fumarate mitochondrial transporter | A7C99_5424 A7C99_5425 A7C99_5426 |

actin monomer binding protein, putative succinate:fumarateantiporter hypothetical protein |

| Orthomcl-55 | A7D00_4766 | Cutinase transcription factor 1 alpha | A7C99_2923 A7C99_2924 A7C99_2925 |

Killer toxin subunits alpha/beta Cutinase transcription factor 1 alpha hypothetical protein |

| Orthomcl-57 | A7D00_5325 | DEAD/DEAH box DNA helicase | A7C99_945 A7C99_946 A7C99_947 |

hypothetical protein DEAD/DEAH box DNA helicase UDP-galactose transporter |

| Orthomcl-59 | A7D00_7080 | phospholipase | A7C99_3575 A7C99_3576 A7C99_3577 |

Phospholipase hypothetical protein small nuclear ribonucleoprotein |

| Orthomcl-60 | A7D00_814 | wd and tetratricopeptide repeat protein | A7C99_4699 A7C99_4700 A7C99_4701 |

hypothetical protein wd and tetratricopeptide repeat protein hypothetical protein |

| Orthomcl-4 | A7D00_5168 A7D00_5823 A7D00_6142 |

beta-glucosidase beta-glucosidase beta-glucosidase |

A7C99_1137 A7C99_1727 A7C99_1728 A7C99_1729 A7C99_1730 A7C99_1731 A7C99_6784 |

Probable beta-glucosidase E hypothetical protein beta-1,4-glucosidase 5′-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase Bud site selection protein 22 sugar isomerase beta-glucosidase |

| Orthomcl-10 | A7D00_1852 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 54 | A7C99_1678 A7C99_5926 A7C99_5927 A7C99_5928 |

Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 54 hypothetical protein cytochrome P450 Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 54 |

Repetitive sequences and transposable elements

Repetitive sequences (RS) have been shown to serve as vehicle to maintain genomic variability and serves evolutionary change (Chibana et al. 2005). Compared to Aspergillus and Candida, T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829 have extremely few repeats (Chibana et al., 2005, Nierman et al., 2005). We identified a total of 77 LRFs (long repeat fragments) in T. rubrum occupying 0.04 % of the global genome, and 166 LRFs in T. violaceum with a percentage of 0.33 %. The number of transposable elements (TEs) was also low, i.e. 46 in T. rubrum (9 209 bp) and 51 in T. violaceum (11 354 bp). A total of 92 retrotransposons were predicted within T. rubrum with a total length of 10 765 bp and 213 in T. violaceum measuring 83 153 bp.

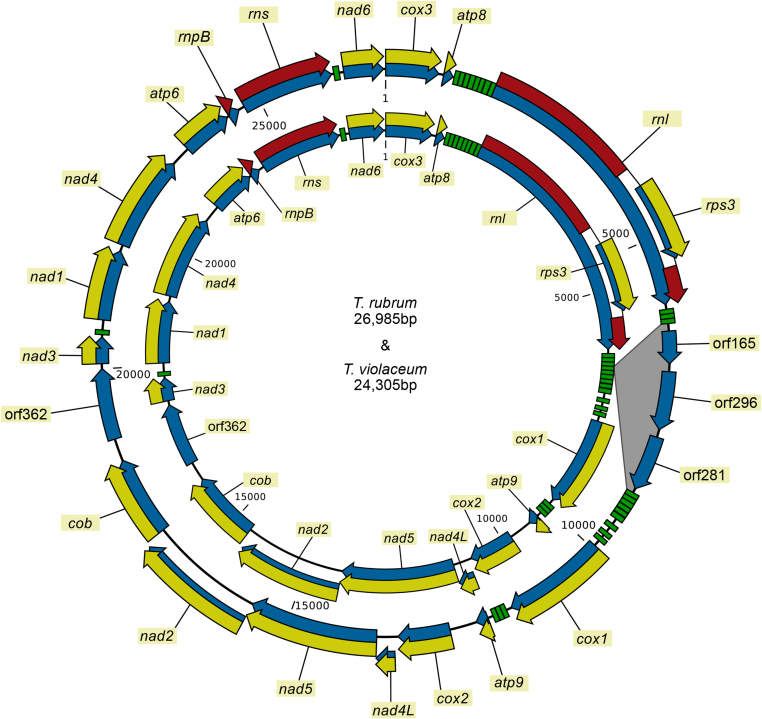

Mitochondria

Mitochondrial genomes were successfully assembled from Illumina reads using Grabb and SPAdes. The mitochondrial genomes assembled into single circular contigs for both species (Fig. 4). The lengths of the sequences were 26 985 bp and 24 305 bp for T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829, respectively. The mitochondrial genomes encoded for 13 proteins typical for filamentous fungi, the rRNAs of the small and large subunit of the ribosome (rns and rnl, respectively) and 25 tRNAs. The rnl gene contained a group I intron that codes for rps3. Both mitochondrial genomes contain a ribozyme gene, rnpB, and an ORF with unknown function between the cob and nad3 genes. The genes in both genomes are in the same orientation and show complete conservation.

Fig. 4.

Mitochondrial genomes of Trichophyton rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829. Green blocks: tRNA coding genes, blue arrows: genes, yellow arrows: protein coding sequences, red arrows: rDNA coding sequence. ORFs are shown with blue arrows without corresponding yellow arrows.

The most striking difference between the two mitochondrial genomes is that there is a 2.6 kb insertion in the mitogenome of T. rubrum between two tRNA genes that are found downstream the rnl gene. The insert is located between trnV(tav) and trnM(cat); in T. violaceum there is only a single nucleotide separating the two genes, while in T. rubrum there is a more than 2.6 kb region separating them. This region contains 3 ORFs, the first of them encodes a putative GIY-YIG endonuclease, the other two have no functional prediction. GIY-YIG endonucleases belong to the homing endonucleases that are frequently found in group I introns.

Functional classification of EggNOG

The gene sequences of T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829 were compared against NCBI, SWISS-Prot, KEGG and EggNOG databases. The prediction of gene function from EggNOG revealed 3 491 orthologous genes which accounted for 48.8 % of entire genome in T. rubrum CBS 139224, while T. violaceum CBS 141829, 6 081 orthologs were generated by EggNOG annotation and took a percentage of 82.01 % of the genome. A comparison of EggNOG classification of T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829 is provided in Table S2.

Although the total numbers of genes annotated by the database tools are similar, the annotation power seems to be different in each category. In main traits T. violaceum and T. rubrum histograms were similar, but the former was consistently somewhat higher, which might due to more orthologous genes annotated in T. violaceum. Genes involved in cell wall biogenesis [M], cell motility [N] and extracellular structures [W] take small percentages in COG classification, related to the lack of reference databases.

Genes related to metabolism

A total of 2 585 genes involved in 277 metabolic pathways were annotated in T. rubrum CBS 139224 according to KEGG functional analysis, while 2 888 genes were predicted for T. violaceum CBS 141829 involving in 174 pathways. Table S3 displays the top-14 pathways containing more than 50 genes. Genes of carbohydrate metabolism corresponding to glycosis/gluconeogenesis, TCG cycle, and degradation of pentose phosphate, fructose, mannose, sucrose, and ketone are all present in T. rubrum and T. violaceum. Key genes responsible for lipid biosynthesis and catabolism were also annotated, including metabolism of triglycerides, glycerophospholipids, and sphingolipids. However, metabolism of arachidonic acid and linoleic acid, and the alpha-linolenic acid pathway were not complete in both fungi analyzed. Trichophyton rubrum and T. violaceum possess all pathways for biosynthesis and metabolism of the 20 basic amino acids. In addition, arginine succinate lyase, ornithine carbamoyl transferase are also identified and so does a complete urea cycle. Critical genes in porphyrin metabolic pathways are enriched; however, chlorophyll synthesis pathway is interrupted in these two dermatophytes.

Most vitamins, such as thiamine, riboflavin, vitamin B6, nicotinate and icotinamide, pantothenate, and CoA biosynthesis, folate and biotin metabolism were all found in T. rubrum and T. violaceum, but ascorbate and aldarate metabolism were missing. Both dermatophytes encode the genes that transfer nitrogen residues to l-asparagine, glycine and l-glutamate and break down the latter into ammonia. The sulfur reduction and fixation pathway is also complete in these two strains. Trichophyton violaceum has been reported to be vitamin B dependent, growing better and sporulating abundantly in vitamin B-rich media (Gräser et al. 2000). Surprisingly, however, the fungus shares this vitamin pathway with T. rubrum and shows no deficiency. Overall, the above analysis demonstrates that T. rubrum and its molecular siblings possess basic metabolic abilities as most eukaryotic organisms.

Mating type locus

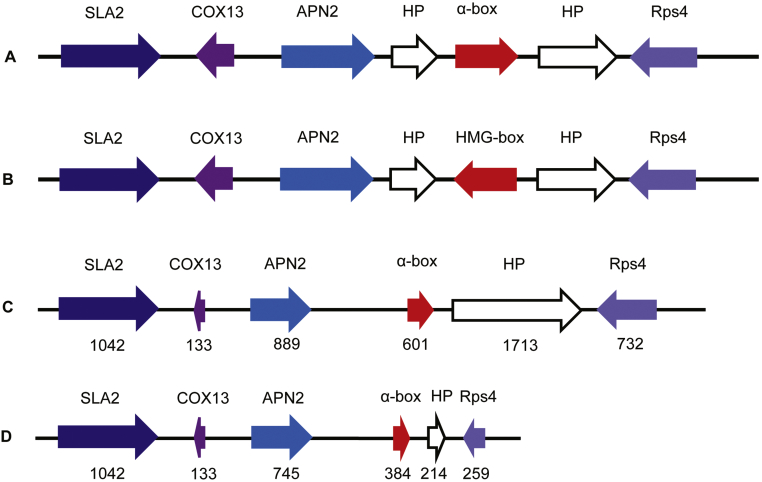

While a sexual life cycle with ascigerous gymnothecia has been described for some zoophilic Trichophyton species, mating within T. rubrum and T. violaceum has not been observed, and it is unclear whether sexuality plays an important role in their natural ecology. Sexual reproduction in heterothallic ascomycetes is governed by a single mating type locus (MAT) with two idiomorphs of highly divergent sequences: either alpha (MAT1-1) or high mobility group, HMG (MAT1-2) (Li et al. 2010). Trichophyton rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829 are identified as of MAT1-1 type, with upstream SLA2, COX3 and APN2 and downstream the 40S rDNA encoding gene as the flanking regions (Fig. 5). With the exception of T. equinum CBS 127.97, which is MAT1-2, all remaining strains are MAT1-1 type. The MAT region, compared in nine dermatophyte species by local blast in the CLC genomics bench, proved to be highly conserved (Fig. 5). Some variation is noted in the number of amino acids of MAT flanking regions of T. rubrum and T. violaceum (Fig. 5C and D).

Fig. 5.

A, B. Approximate MAT1-1 locus of dermatophytes. A. Locus as present in T. rubrum CBS 118892, T. tonsurans CBS 112818, T. verrucosum HKT0517, T. benhamiae CBS 112371, N. gypsea CBS 118893, and M. canis CBS 113480. B.MAT1-2 locus present in T. equinum CBS 127.97. C, D.MAT1-1 locus with numbers of amino acids. C.T. rubrum CBS 139224. D.T. violaceum CBS 141829.

Adhesion

Following previous reports, six web servers/platforms with fungal adhesin predictors were consulted to search putative adhesin-like proteins (see Methods). However, unexpected results of these applications emerged. Firstly, the online database of Faapred can only receive 25 sequences each time, which is not applicable for genome data. Secondly, Fungal RV is suitable for prediction for some medically important yeasts and Aspergillus strains (Chaudhuri et al. 2011), but results were inappropriate for dermatophytes: e.g. 5 probable adhesins were yielded for T. rubrum CBS 118892 and 25 for T. rubrum CBS 139224. Thirdly, GPI-anchor Predictor has a similar problem as Fungal RV, with unstable results for dermatophytes. For these reasons three software products were selected for our prediction, i.e. SignalP, GPI-modification and TMHMM Server, which produced consistent results among nine genomes. Putative adhesins were chosen with the following parameters: SignalP 4.0 positive; TMHMM 2.0 < 1 helices and number of AA to exclude as 45 from N-terminus and 35 for C-terminus; Big-PI positive.

Table S4 lists the probable adhesins for nine dermatophytes. Nannizzia gypsea carried only five adhesins, while Microsporum canis had 17 adhesins. In Trichophyton, the number varied from 20 to 26, most being hypothetical proteins but some were known adhesins and GPI-anchor proteins, e.g. EGE03127.1 of T. equinum and EEQ28337.1 of M. canis. These sequences are ecm33, a gene encoding adhesins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. EFQ97364.1 and EFQ97072.1 of N. gypsea are gel4 and gel12, important genes facilitating adherence of A. fumigatus (Free 2013). Among the 21 genes predicted as adhesins for T. rubrum, 17 sequences are very similar to those of T. violaceum, which implies that T. rubrum has four specific adhesins and T. violaceum has eight.

Secreted proteases

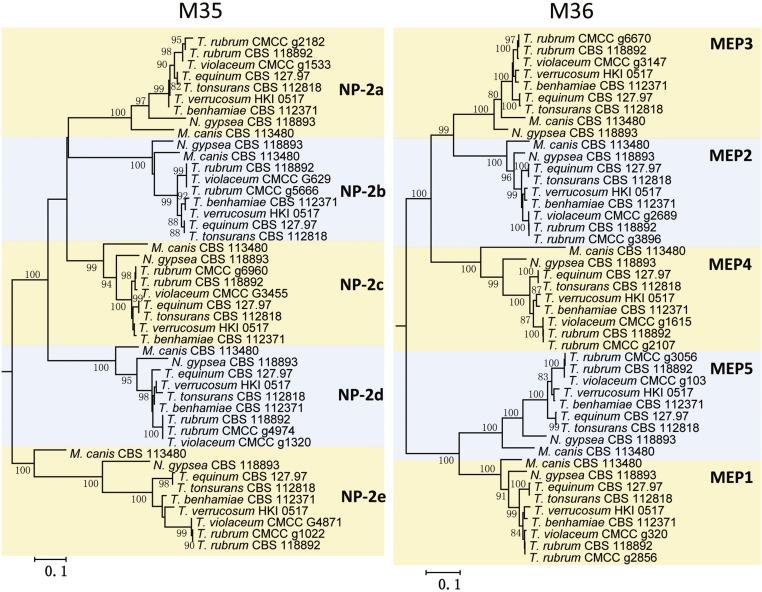

Three kinds of endoproteases belonging to three families were analyzed in the nine dermatophytes under study, including metalloproteases (M36 family), deuterolysins (M35 family) and subtilisins (S8A family) (Li and Zhang, 2014, Tran et al., 2016, Martinez et al., 2012). Five duplicated genes belonging to metalloprotease and five genes belonging to deuterolysin persist in the genomes. M35 family members have high sequence similarity with neutral protease 2 and clustered in the M35-A clade (Li & Zhang 2014), which is specific for Arthrodermataceae. The different protease families showed comparable patterns of similarity, with four clusters: (1) T. tonsurans and T. equinum, (2) T. verrucosum and T. benhamiae, (3) T. rubrum and T. violaceum, and (4) M. canis and N. gypsea. This corresponds to known phylogenetic distances where sequences of T. rubrum and T. violaceum are highly similar, rather closely related to other T. tonsurans/ equinum, while Microsporum and Nannizzia are remote (Rezaei-Matehkolaei et al., 2014, de Hoog et al., 2017). Previous studies suggested that exoprotease genes have expanded independently (Li & Zhang 2014). The non-rooted trees of M35 and M36 showed similar topology suggesting that the families evolve with comparable speed, and the clustering was largely consistent with known phylogenetic relationships among the studied fungi. For this reason, we denominated the M35 genes as NP-2a to NP-2e in the order of MEP1‒5 genes, for easy comparison (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Non-rooted Maximum likelihood trees of dermatophyte deuterolysins (M35 family) and fungalysins (metalloproteinases, M36 family) constructed with Mega v. 6.0 with 500 bootstrap replications. *M35 family members denominated herewith.

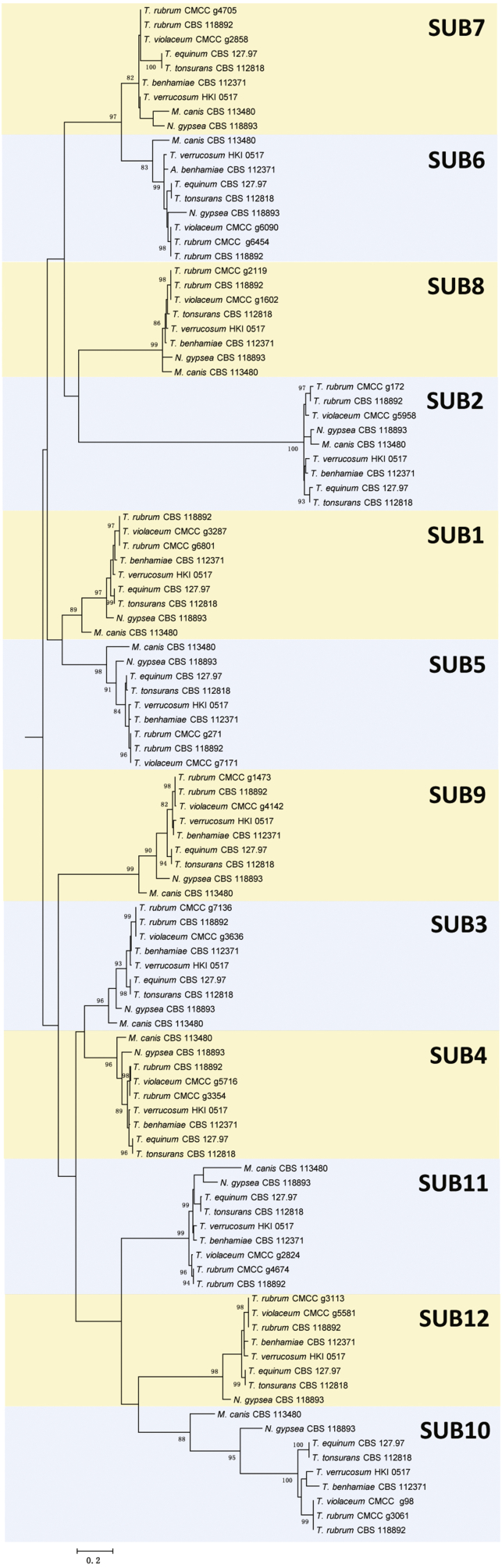

A total of 106 sequences were identified in the S8A family, comprising 12 sequences types which designated as Sub1 to Sub12 in the tree, except for Sub12 which was lost in M. canis and Sub8 lost in T. equinum (Fig. 7, Table S5). Two other subtilisin-like proteases (A7D00_1654 and A7D00_4929) which also contained an S8 domain were found in the genome of T. rubrum CBS 139224, but they had low identity with the classical S8A family. No similar sequences were found in T. violaceum CBS 141829. The S8A family showed much more diversity and a correspondence with phylogenetic relations was noted, as Sub7 is much closer to Sub6 and Sub8 and Sub2 may have evolved from this ancestor. The sequences could be grouped in two main clusters, with the upper one including Sub7, Sub6, Sub8, Sub2, Sub1 and Sub5, while the lower contained Sub9, Sub3, Sub4, Sub11, Sub12 and Sub10. Comparing the dendrogram of dermatophyte proteinase trees to the ribosomal tree, a similar topology became apparent. Members within the above families are listed in Table S5.

Fig. 7.

Non-rooted Maximum likelihood trees of dermatophyte secreted proteases (S8A families) constructed with Mega v. 6.0 with 500 bootstrap replications.

In addition to endoproteases, exoproteases play an important role in the degradation of hard keratin; these include dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV), dipeptidyl peptidase V (DPPV), leucine aminopeptidases (LAPs), carboxypeptidase A (MCPA), carboxypeptidase B (MCPB), carboxypeptidase S1 homolog A (SCPA), and carboxypeptidase S1 homolog B (SCPB) (Monod, 2008, Tran et al., 2016). SED1and SED2 are genes belonging to tripeptidyl-peptidases which degrade proteins at acidic pH and are known to be involved in virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus (Reichard et al. 2006). Genes A7D00_5713 and A7C99_545 have high identity (over 90 %) with SED2 of A. fumigatus, but for SED1 no homologs were found. All proteinases annotated were displayed in Table S6.

Secondary metabolism

Table S7 lists the results of secondary metabolism of T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829. Totally nine metabolite clusters are present in both fungi, seven of which are conserved. Additionally, there is an ochratoxin A biosynthetic gene cluster specific for T. rubrum with high identity (66 %) to Penicillium nordicum (AY557343), which is absent in T. violaceum. Two specific clusters, i.e. patulin biosynthetic and fusaridione A biosynthetic gene cluster, seem to be present in T. violaceum, but the results are uncertain, with only 13 % and 12 % identity with reference sequences.

Discussion

The family Arthrodermataceae has recently been revised on the basis of molecular phylogeny (de Hoog et al. 2017). Ancestral, mostly geophilic dermatophytes with thick-walled macroconidia were placed in Arthroderma, while Trichophyton was restricted to a clade which covers all anthropophiles in addition to some zoophilic species. Ribosomal genes ITS and partial LSU are sequenced as standard, but in order to obtain better resolution, TUB2, RP 60S L1, TEF3 were included in addition. Surprisingly and in conflict with most other groups of filamentous fungi, best resolution (highest number of supported clades) was obtained with ITS (Table 3). Monophyly was confirmed for the currently distinguished seven genera (de Hoog et al. 2017). All seven genera were represented as clades by ITS with BS > 80 %, and for Nannizzia ITS was even the only marker with sufficient support. Average performance was achieved with TUB2 and RP 60S L1, while LSU and TEF3 had very poor performance.

The final phylogenetic overview of Arthrodermataceae was reconstructed on the basis of ITS is used as barcoding marker, with Guarromyces ceretanicus as outgroup in the tree constructed with Maximum likelihood using Raxml v. 8.0.0 under gtrcat model and 1000 bootstrap replications (Fig. 2). The obtained phylogeny has a topology which in main traits confirmed early phylogenies published by Gräser et al. (2000), with seven bootstrap-supported clades now recognized as genera (de Hoog et al. 2017). Since Homo sapiens is the phylogenetically most recent mammal host of dermatophytes, the strictly anthropophilic species should appear in derived position in the tree. Arthroderma, comprising prevalently geophilic species, is found as an ancestral group. Arthroderma contains 21 currently accepted, mostly well-resolved species associated with burrows and furs of wild animals. Species occurring on domesticated animals are found near the anthropophiles (Fig. 2). Accordingly, the tree shows an evolutionary trend of increasing association with mammal hosts. We may assume that this reflects a true phylogenetic history and therefore it can be expected that the tree is robust, providing stable nomenclature.

While Arthroderma species are easily distinguished with large barcoding gaps, and frequently produce elaborate gymnothecial sexual states, the anthropophilic Trichophyton species are difficult to distinguish molecularly, and no sexual fruit bodies are known. Some species are phenotypically reduced, in culture just producing hyphal elements or chlamydospore-like structures. Significant adaptations are needed to colonize the hairless human skin, which may explain the loss of sexuality and reduced conidiation. Transmission takes place by skin flakes rather than by conidia or ascospores.

The close affinity of clinically different entities poses a diagnostic problem. The species T. violaceum is a highly specialized sibling of T. rubrum, having a predilection for the human scalp, while T. rubrum is found on skin and nails. As an alternative, it may be hypothesized that T. violaceum is just a phenotypically different strain of T. rubrum that has emerged because of differences in physiological stress exerted in different habitats. For correct affiliation of species and determination of species borderlines, understanding of virulence and adaptation are essential.

Epidemiological analyses suggested that the Trichophyton rubrum originated with humans in Africa and subsisted on this continent for a long time, often without causing significant disease (Gräser et al. 1999). This changed around the end of the nineteenth century when the fungus was transported on a worldwide scale via human travels and social activities. The fungus was also introduced to the Western world and became epidemic due to the preference of wearing closed leather shoes and sneakers as a part of modern life style (Gräser et al., 2000, Gräser et al., 2007, Dismukes et al., 2003). In contrast, its close relative T. violaceum has remained in some endemic pockets in Africa and Asia as an agent of tinea capitis (Zhan et al. 2015) and was brought to Europe mainly by scattered, recent immigration events; it shows no tendency to epidemic expansion (Nenoff et al. 2014). In contrast to the globally widespread T. rubrum, T. violaceum as an endemic fungus is restricted to semiarid climate zones of the Mediterranean, Northern Africa, Iran and Northwestern and Southern China (Ayanbimpe et al., 2008, Patel and Schwartz, 2011, Zhan et al., 2015). Using microsatellites, Ohst et al. (2004) demonstrated that T. violaceum showed more variation, while T. rubrum was nearly monomorphic suggesting a founder effect after adaptation to a new ecological niche. As a zoophilic species, Trichophyton benhamiae causes inflammatory disease when transmitted to humans (Drouot et al. 2009), while obligatorily anthropophilic species such as T. rubrum show low inflammation. In addition, the zoophile T. benhamiae is sexually competent. Li et al. (2010) reported that common features of the MAT locus are shared among five common dermatophytes (N. gypsea, M. canis, T. equinum, T. rubrum and T. tonsurans). Evolution of the MAT locus apparently is not synchronous with that of ecologically relevant parameters, and occasional successful mating between classical species can be observed (Kawasaki 2011). Our data in nine dermatophytes are consistent with these reports showing that the MAT locus is shared among species. Both T. rubrum and T. violaceum presented as MAT1-1 mating type in our study, suggesting drift of unbalanced mating types leads to loss of mating in anthropophilic species (Gräser et al. 2008).

Genome sequencing has become one of the conventional means to study the biology and ecological abilities of microbes. Pacific Biosciences developed the single-molecule real-time sequencing technique (SMRT) which enables long reads (up to 23 000 bp) and has high efficiency of 1 080 Mb each run. However, the raw data generated from the PacBio RS platform is inherently error-prone, with up to 17.9 % errors having been reported (Chin et al. 2011). Most of these concerns indel events caused by incorporation events, or intervals that are too short to be reliably detected (Eid et al. 2009). The PacBio platform has been widely used in viruses, bacteria and small genome size organisms, but thus far rarely for fungi of medical interest. In our study we applied two genome sequencing platforms to obtain maximum genome quality, i.e. an Illumina platform with high accuracy, as well as a PacBio RS platform which allows long reads. Considering the high consistence of the compared species, and given the high cost of PacBio, there is no need for additional SMRT sequencing of T. violaceum. Trichophyton rubrum CBS 139224 yielded sequences with less scaffolds and with an N % as low as 0.055 %, which is much better than the presently available genome of T. rubrum CBS 118892. In addition we reconstructed the complete mitochondrial genome of T. rubrum CBS 139224 and T. violaceum CBS 141829, which showed high similarity to the previous report on this species (Wu et al. 2009).

The oriental strain T. rubrum CBS 139224 had a genome size of 22.3 Mb, CBS 118892 was published to be 22.5 Mb, while T. violaceum (CBS 141829) had 23.4 Mb. The genomes were compared with each other and with seven dermatophyte species available in the public domain. Four Trichophyton species ranged in size from 22.6 to 24.1 Mb. Draft genomes of dermatophytes show very high degrees of conservation, both at nucleotide and at amino acid levels (Martinez et al. 2012).

Most genomes of Eukaryotes, including fungi contain significant amounts of repetitive DNA, which usually occur in multiple copies and are with or without coding domains. In Candida albicans, major repeat sequences (MRS) have been identified in all but one chromosome (Lephart & Magee 2006). The Aspergillus fumigatus genome harbors rich duplication events, the majority clustering in 13 chromosomal islands, which are related to pathogenesis of clinical strains (Fedorova et al. 2008). Copy numbers and location may differ between populations and are stably inherited; the elements have widely been used in epidemiological profiling. Contrary to these fungi, dermatophytes show an extraordinarily high coherence at nucleotide and gene level, with very few repeat elements in the genome. These data indicate that dermatophytes are consistent pathogens with a short divergence time; very few genetic events occurred in the evolutionary history of dermatophytes.

Secreted proteases are key virulence factors for dermatophytes. Two types of endo-proteases are prevalent in dermatophytes, i.e. subtilisins belonging to the S8A family, and metalloproteinases which comprise two different subfamilies, the deuterolysins (M35) and the fungalysins (M36) (Monod, 2008, Li and Zhang, 2014). These proteases share high consistence among members of the same family, but have low degrees of identity among different families (Li & Zhang 2014). The protease families M35 (deuterolysins) and M36 (fungalysin) are among the most important metalloproteinases, in which zinc is an essential metal ion required for catalytic activity. These genes are found in numerous pathogenic fungi, but show expansion in Arthrodermataceae (dermatophytes) and Onygenaceae (the family containing Coccidioides; Li & Zhang 2014). Members of the M35 and M36 families seem to be highly conserved among dermatophytes with signatures that are specific for Arthrodermataceae and have low identity with other Onygenales (Li & Zhang 2014). In our study, M35 and M36 have the same five copies in all nine dermatophytes. As suggested by Li & Zhang (2014), M35 duplicated and M36 was lost in Coccidioides compared to dermatophytes, probably due to different life styles of these fungi as systemic and cutaneous pathogens, respectively.

Thus far twelve subtilisin-encoding genes within the S8A family have been reported (Martinez et al. 2012) and in our study, they were successfully annotated in nine genomes (see Methods), with the exception of M. canis (Sub12 lost) and T. equinum (Sub8 lost), which both have their natural niche in animal fur (Martinez et al. 2012). Phylogenetically, T. rubrum (human skin) is close to T. violaceum (human scalp), T. equinum (horse) is close to T. tonsurans (human skin), and T. verrucosum (cattle) close to T. benhamiae (guinea pigs), while all these species are remote from Microsporum canis (dog) and Nannizzia gypsea (soil). These data matched well with known phylogenetic relationships (de Hoog et al. 2017). A high degree of similarity was found between T. rubrum and T. violaceum; no unambiguous protease difference explaining the clinical difference between the two species was found, suggesting that the divergence between the entities concerns a very recent evolutionary event.