Abstract

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most frequent episodic vestibular disorder. It is due to otolith rests that are free into the canals or attached to the cupulas. Well over 90% of patients can be successfully treated with manoeuvres that move the particles back to the utriculus. Among the great variety of procedures that have been described, the manoeuvres that are supported by evidenced-based studies or extensive series are commented in this review. Some topics regarding BPPV treatment, such as controlling the accuracy of the procedures or the utility of post-manoeuvre restrictions are also discussed.

Keywords: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo, Treatment, Vestibular disorder

1. Introduction

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) is the most frequent vestibular disorder, with a life time prevalence of 10% (von Brevern et al., 2007). It is characterized by rotational vertigo induced by head position changes, especially when extending or turning the neck, lying down or rolling over in bed.

There are two accepted theories supporting BPPV, known as canalolithiasis and cupulolithiasis (Honrubia et al., 1999, House and Honrubia, 2003).

Canalolithiaisis refers to the presence of cumulates of otolith rests that are free into the canals. Whereas they are displaced according to the head movements, an endolymphatic current that abnormally stimulates the cupula is generated, leading to clinical symptoms.

Cupulolithiasis involves a deposit of otolith rests adhered to the cupula of the canal, changing its specific gravity. Thus, the cupula is made sensible to linear accelerations, such as the acceleration of gravity.

Canalolithiasis are more frequent than cupulolithiasis, as the former needs less mass to be symptomatic. It has been calculated that a mass of particles of 0,087 ug are required for a canalolithiasis in contrast to cupulolithiasis, that needs a mass of at least 0,69 ug to be provoqued (House and Honrubia, 2003).

These two variants of BPPV means different characteristics of the nystagmus elicited by the provoking manoeuvres. Canalolithiasis nystagmus is brief (lasting less than a minute), paroxysmal and it is preceded by a latency of few seconds. On the contrary, cupulolithiasis nystagmus has no latency or a brief one and lasts more than a minute.

Recently, the Committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society has stablished the criteria for the diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (von Brevern et al., 2015). It is based upon physiopathology, considering canalolithiasis and cupololthiasis of every canal as different sub-entities. Although BPPV might affect every canal, this document only recognizes the forms that have been documented by eye movements recording. Thus, cupulolithiasis of the anterior canal has not been considered.

Diagnosis of BPPV is made by specific test that exposes each canal to gravity, causing a nystagmus that matches the stimulation of the canal. A canalolithiasis or a cupulolithiasis will be determined by the latency and the duration of the nystagmus.

Given that the treatment of choice for BPPV, the repositioning manoeuvres, are intended to move the particles from the semi-circular canals to the utriculus, diagnosis is crucial for the treatment planning.

2. Treatment of the posterior canal canalolithiasis (pc-BPPV)

Posterior canal canalolithiasis is the most frequent variant of BPPV, accounting for 80–90% of cases. It is diagnosed when a Dik-Hallpike or a side-lying test elicits a torsional nystagmus with the upper pole of the eyes beating toward the lower ear combined with vertical nystagmus beating upward, that lasts less than a minute and is precluded by a short latency (von Brevern et al., 2015).

It has been extensively proved that Epley (1992) (Fig. 1) and Semont (Semont et al., 1988) (Fig. 2) manoeuvres are both suitable for treating pc-BPPV. The results, measured as the number of manoeuvres required for clearing the symptoms and the nystagmus, are comparable (Fife et al., 2008, Helminski, 2014, Liu et al., 2016). Only a small difference was found in the posterior to horizontal canal switch rate between both manoeuvres, being slightly more frequent in Epley manoeuvre than in Semont one (Anagnostou et al., 2014). Given that speed of rotation is critical for a successful Semont manoeuvre whereas adequate neck extension and flexibility is required for a successful Epley treatment (Faldon and Bronstein, 2008), choosing one of them depends on the particular features of the patients, such as weight or neck mobility.

Fig. 1.

Epley manoeuvre for treating posterior canal canalolithiasis (depicted for a right-sided pc-BPPV). 1) The patient is seated with the head turned 45° to the affected side (right in this case). 2) The patient is tilted back with the neck in slight extension. 3) The head is turned 90° to the healthy (left in this example) side. 4) The entire body is rotated 90° until the patient is laying on the healthy side, while keeping the head position against the trunk. 5) The patient is raised to the initial position. Then the head is turned towards the front. Each position is maintained 1 min or until the induced nystagmus has extinguished.

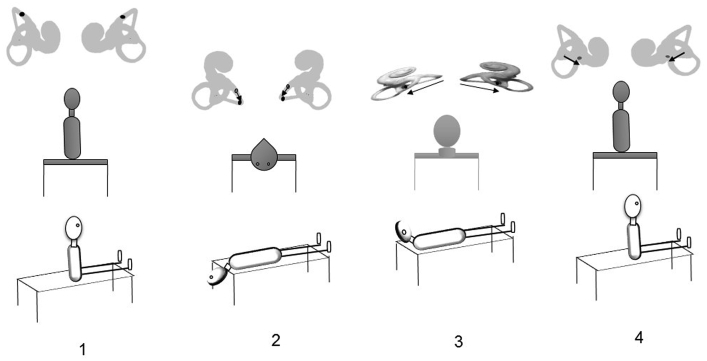

Fig. 2.

Semont manoeuvre for treating posterior canal canalolithiasis (exemplified for a right-sided pc-BPPV). 1) The patient is seated with the head turned 45° to the healthy side (left in this case). 2) The patient is quickly moved to lie on the affected side (right in this picture). 3) The patient is suddenly turned 180° to lay on the unaffected side while maintaining the position of the head relative to the trunk. 4) The patient is raised to the initial position.

Brandt-Daroff exercises cannot be considered as first choice treatment because it has been proved to be significantly less effective than Epley and Semont procedures (Amor-Dorado et al., 2012, Soto Varela et al., 2001). Brandt-Daroff exercises are designed to disperse the canaliths and to increase the patient's tolerances for the BPPV symptoms; thus, they cannot be classified as a repositioning procedure. Nevertheless, Brandt-Daroff exercises might be useful in selected cases combined to Epley or Semont manoeuvres (Soto-Varela et al., 2012).

For successful repositioning, the particles should be moved away from the ampulla to the dependent position during each step of the Epley or the Semont manoeuvres (Faldon and Bronstein, 2008). This means that a nystagmus indicating ampullofugal migration may be observed (Epley, 2001). This nystagmus, beating upward with a torsional component toward the involved ear, is called orthotropic nystagmus and is a sign of an appropriate migration of the particles toward the utriculus (Fyrmpas et al., 2013, Oh et al., 2007, Soto-Varela et al., 2011). While the appearance of the orthotropic nystagmus is a sign of good prognosis, the lack of such nystagmus does not mean that the manoeuvre will not be effective. This absence of nystagmus could be due to otoconial debris disintegration so that a correct displacement is nevertheless incapable of generating a sufficient endolymph flow to trigger an observable nystagmus (Fyrmpas et al., 2013, Oh et al., 2007, Soto-Varela et al., 2011). Conversely, a reversed pattern of positioning nystagmus during the manoeuvre indicates a ampullopetal migration of the debris and points to a repositioning failure (Fyrmpas et al., 2013, Oh et al., 2007, Soto-Varela et al., 2011).

In sum, for an optimal control of its realization, the observation of the nystagmus during the therapeutic manoeuvres is highly recommended (Paz Pérez-Vázquez, Virginia Franco-Gutiérrez, Andrés Soto-Varela et al., 2017).

The original description of the Epley manoeuvre included the use of a mastoid vibrator device. The mastoid vibration would contribute to disperse the particles that form the canalith, helping the manoeuvre to resolve the BPPV. Macias et al. found no evidence of benefit for mastoid oscillation applied during the Epley manoeuvre (Macias et al., 2004) and a Cochrane review has supported this statement (Hunt et al., 2012). However, the mastoid oscillation may help to mobilize the particles when they are jamming within the canal (the so called canalith jam) (Epley, 2001).

Epley also recommended patients to keep their heads upright for two days following the procedure, in order to prevent particles from moving back to the posterior canal (Epley, 1992). With this aim in mind, other classical restrictions have been stated, such as to avoid sudden head movements, to wear a cervical collar and to avoid lying on the affected side (Cakir et al., 2006). Several studies have been conducted to clarify this topic, most of them failing to show a benefit from postural restrictions (Casqueiro et al., 2008, De Stefano et al., 2011, Devaiah and Andreoli, 2010, Fyrmpas et al., 2009, Ganança et al., 2005, Marciano and Marcelli, 2002, Moon et al., 2005, Papacharalampous et al., 2012, Roberts et al., 2005). In a Cochrane review (Hunt et al., 2012), the conclusion is that there is a statistically significant effect of post-Epley postural restrictions in comparison to Epley manoeuvre alone (Semont manoeuvre was not evaluated in this study), but the improvement in treatment efficacy is very small.

Since Foster et al. (2012) published their results, it has been widely accepted that performing the provocative testing just after the completion of the treatment will favour the particles to flow back into the posterior canal or to enter in another canal. Although Gordon et al. (Gordon and Gadoth, 2004), in a previous study found that a single session of repeated manoeuvres seemed to be superior to one single procedure and well tolerated, this issue has not been extensively studied. Nowadays the usual practice is to perform a single therapeutic manoeuvre by session.

There is no consensus about the optimal time to test the effectivity of the manoeuvre. On one hand, to do it immediately may favour the reflux of the canalith and repeated positioning may also show a false successful treatment due to a fatigue response (Foster et al., 2012, Helminski et al., 2010). On the other hand, 30% of the patients with pc-BPPV may experience a spontaneous remission after a week (Imai T, Ito M, Takeda N, Uno A, Marsunaga T, Sekine K, 2005), resulting in a successful result, wrongly attributed to the treatment manoeuvre. Even more, a long-term trial may show a false positive provoking test due to a recurrence (Helminski et al., 2010). When a canalith enters the utriculus it is expected to be dissolved in the low calcium containing normal endolymph. As normal endolymph can dissolve an otoconia in about 20 h (Zucca G, Valli S, Valli P, Perin P, 1998), the empiric period of 24 h suggested by some authors should be appropriate. Nevertheless, the optimal time interval between treatment and outcome assessment has not been yet stablished.

Pc-BPPV is usually resolved with one to three manoeuvres (Song et al., 2015, Soto-Varela et al., 2012, Steenerson et al., 2005), being considered a benign disease. But sometimes daily practice supply clinicians with difficult cases, the so called intractable BPPV(Choi et al., 2012, Horii et al., 2010). Intractable BPPV comprises 1) persistent BPPV (which continues despite appropriate physical therapy), and 2) recurrent BPPV (frequent relapses after the disappearance of the initial symptoms and nystagmus). The incidence of persistent BPPV has been estimated for 12.5% and recurrent BPPV for 10–25% (Choi et al., 2012, Pérez et al., 2012, Soto-Varela et al., 2012).

During the last few years many factors involved in the intractability of BPPV have emerged. Potential risk factors associated to the BPPV treatment failure are: age over 50 years old, secondary BPPV, head trauma, the concurrency of comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension and osteoarthrosis, ductal inflammatory narrowness, osteoporosis and vitamin D deficiency (Babac et al., 2014, Bela et al., 2013, De Stefano et al., 2014, Ogun et al., 2014, Parham et al., 2013, Pérez et al., 2012, Talaat et al., 2014).

Intractable BPPV management is mainly based on repeating repositioning manoeuvres. Recently, treatments based upon the putative risk factors of intractability have merged, such as corticosteroid intratympanic treatment (Pérez et al., 2016) and D vitamin intake (Talaat et al., 2016). Surgical treatments, such as posterior canal blocking and singular nerve section, should be the final step (Kisilevsky et al., 2009, Leveque et al., 2007).

3. Treatment of the horizontal canal BPPVs

Horizontal canal canalolithiasis (hc-BPPV) is diagnosed when the supine roll test elicits a horizontal nystagmus beating toward the undermost ear (geotropic direction changing nystagmus), after a brief latency or no latency and lasting less than a minute. Horizontal canal cupulolithiasis (hc-BPPV-cu) is diagnosed when the supine roll test provokes a nystagmus beating horizontally to the uppermost ear (apogeotropic direction changing nystagmus), after a brief latency or no latency and lasting more than a minute (von Brevern et al., 2015).

A third variant may be considered. It is the canalolithiasis of the anterior arm of the horizontal canal. The diagnosis is based on the supine roll test eliciting a horizontal nystagmus beating towards the uppermost ear (apogeotropic direction changing nystagmus), after a brief latency or no latency and lasting less than a minute (Aw et al., 2005, Pérez-Vázquez et al., 2017).

Apogeotropic and geotropic variants have similar treatments but very different positions are concerned. Besides, knowing the affected side plays a crucial role in the manoeuvre development (Paz Pérez-Vázquez, Virginia Franco-Gutiérrez, Andrés Soto-Varela et al., 2017). The pathologic ear can be identified by applying the Ewald's second law: the quick phases of the most intense nystagmus point to the affected side (Pérez-Vázquez et al., 2017, von Brevern et al., 2015); but, many times it is difficult to recognize the stronger nystagmus. The bow and lean manoeuvre (Choung et al., 2006, Kim et al., 2016, Lee et al., 2010; von Brevern et al., 2015; Yetiser and Ince, 2015) may be very useful and, in case of cupulolithiasis, the pseudospontaneous nystagmus (Asprella-Libonati, 2014, Asprella-Libonati, 2008, von Brevern et al., 2015) can also help to identify the pathologic side.

Because horizontal canal BPPV is less frequent than pc-BPPV, there are less series about its treatment. Several therapeutic procedures have been described (Korres et al., 2011, Asprella-Libonati, 2005, Riga et al., 2013), although Gufoni's manoeuvres and Lempert manoeuvre (barbeque manoeuvre, Fig. 3), together with head shacking manoeuvre, have been tested using prospective, randomized and placebo-controlled trials (Kim et al., 2012a, Kim et al., 2012b; Mandalà et al., 2013). Other manoeuvres to be mentioned are Forced Prolonged Position (Chiou et al., 2005) or the modification to the barbeque procedure proposed by Tirelli (Tirelli and Russolo, 2004) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Lempert (Barbeque) manoeuvre for treating horizontal canalolithiasis (depicted for a right-sided hc-BPPV). 1) Starting supine position. 2) Head rotation toward the healthy side. 3) Head rotation the nose down position. 4) Final head turn to the affected-ear-down position and sitting up. (The body is rotated between the head movements). Each position is maintained for 60 s or until the provoked nystagmus is dissipated. If the manoeuvre is going well, the quick phases of the nystagmus should beat to the healthy side (ampullofugal nystagmus).

Fig. 4.

Tirelli manoeuvre for treating horizontal canal cupulolithiasis (depicted for a right cupulolithiasis). 1) Starting supine position. 2) The head is first rotated to the affected side. 3) The head is rotated to the healthy side. 4) Head rotation the nose down position. 5) Final head turn to the affected-ear-down position and sitting up. (The body is rotated between the head movements). Each position is maintained for 60 s or until the provoked nystagmus is dissipated. If the manoeuvre is going well, the quick phases of the nystagmus should beat to the healthy side (ampullofugal nystagmus).

Gufoni's manoeuvres deserve special attention since two types of Gufoni's treatments can be considered and certain confusion may be caused. The first Gufoni manoeuvre was described for treating horizontal canal canalolithiasis and sometimes it is called Gufoni for the geotropic variant manoeuvre (Appiani et al., 2002) (Fig. 5). But there is a second variant, at times named as Gufoni for the apogeotropic variant, designed for treating horizontal canal cupulolithiasis or anterior arm canalolithiasis (Appiani et al., 2005).Most of the times Gufoni Manoeuvre, without any other description, is simply cited. As the first description of this variant was done by Appiani and cols (Appiani et al., 2005), we suggest employing the term Appiani manoeuvre for a better understanding of the treatment that is being described (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Gufoni manoeuvre for treating canalolithiasis of the horizontal canal (depicted for a right-sided hc-BPPV). 1) Patient seated head-straight 2) The patient is brought down on the healthy side from the sitting position. 3) The head is turned down 45° (nose is on the bed). 4) The patient is returned to the upright position. Each position is maintained for 60 s or until the provoked nystagmus is dissipated. If the manoeuvre is going well, the quick phases of the nystagmus should beat to the healthy side (ampullofugal nystagmus).

Fig. 6.

Appiani manoeuvre for treating cupulolithiasis and anterior arm canalolithiasis of the horizontal canal (depicted for a right-sided horizontal canal cupulolithiasis). 1) The patient is seated head-straight. 2) The patient is brought down on the affected side from the sitting position. 3) The head is turned 45° upright (nose directed upward). 4) The patient is returned to the upright position. Notice that the canalith may just reach the posterior arm of the canal, instead of attaining the utriculus. Each position is maintained for 60 s or until the provoked nystagmus is dissipated. If the manoeuvre is going well, the quick phases of the nystagmus should beat to the healthy side (ampullofugal nystagmus).

Hc-BPPV can be resolved with a single manoeuvre such as Lempert or Gufoni manoeuvres (Kim et al., 2012b, Asprella-Libonati, 2005). But hc-BPPV-cu or the canalolithiasis of the anterior arm may need a second procedure, provided that many times the initial procedure moves the canalith just to the posterior arm of the canal, converting an apogeotropic form in a geotropic one (Kim, J S, Oh SY, Lee SH, Kang JH, Kim DU, Jeong SH, Choi KD, Moon IS, Kim BK, Oh HJ, 2012a). In fact, the original description of the Appiani manoeuvre includes a subsequent Gufoni manoeuvre to complete de treatment (Appiani et al., 2005). An excellent procedure to test the manoeuvre is the bow and lean test; once the affected side is known, this test can be useful to check for persistence of particles inside the horizontal canal and to know if they have reached its posterior arm. For example, a right hc-BPPV-cu would show a right-beating nystagmus when bending and a left-beating nystagmus when bowing; If the treatment has lead the canalith to the posterior arm of the canal, then the nystagmus should be right-beating when bowing and left-beating when leaning (besides, the nystagmus should be shorter as it is expected for a canalolithiasis).

The questions about the proper time to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment or the relevance of post-manoeuvre restrictions have not been taken into consideration for the horizontal canal BPPV. The number of the manoeuvres by session has not been studied yet. Bearing in mind that the horizontal canal is the most exposed to natural head movements it has been said that its incidence is underestimated because it easily recovers in a spontaneous way (up to 50% of patients suffering for horizontal canal BPPV may experience a spontaneous remission after a week) (Imai T, Ito M, Takeda N, Uno A, Marsunaga T, Sekine K, 2005); in fact, horizontal canal is the most frequent target for the debris to re-entering after treating other canals BPPV(Epley, 2001, Steenerson et al., 2005). The effectivity of the treatment manoeuvres is slightly inferior for the horizonal canal than for the posterior one as well, especially for the cupulolithiasis (Kim et al., 2012a, Kim et al., 2012b). Thus, some intriguing questions regarding the horizontal canal BPPV behaviour are yet waiting to be clarified.

Recently, two types of cupulopathy, the so called light and heavy cupula, have merged as possible subjects for the differential diagnosis with horizontal canal BPPV. The heavy cupula would match exactly the diagnostic criteria for cupulolithiasis of the horizontal canal and the light cupula would be like a canalolithiasis but the nystagmus is persistent, without latency and a pseudo-spontaneous nystagmus beating to the healthy side is showed. Obviously, since they are not BPPV forms, these cupulopathies will be resistant to repositioning manoeuvres (Hiruma et al., 2011, Imai et al., 2014, Imai et al., 2009, Kim et al., 2015, Kim et al., 2014, Schratzenstaller et al., 2001).

4. Treatment of canalolithiasis of the anterior canal (ac-BPPV)

Canalolithiasis of the anterior canal is rare, probably related to the anatomical orientation of the canal (Andrés Soto-Varela et al., 2013b). The diagnosis is made by the Dix-Hallpike test and/or the straight head-hanging position. These tests elicit a nystagmus that beats predominantly vertically downward after a latency of few seconds and lasts less than a minute. This nystagmus has a torsional component which defines the affected side, since both Dix-Hallpike tests and the straight head-hanging test stimulate both anterior canals at the same time. The torsional component should be clockwise when the BPPV lies in the left side and counterclockwise when it is in the right one. But, many times, this torsional component is difficult to notice (Pérez-Vázquez et al., 2017, von Brevern et al., 2015).

Perhaps due to the mentioned diagnostic difficulties, the most popular therapeutic procedure is the manoeuvre described by Yacovino y cols (Yacovino et al., 2009) (Fig. 7). This manoeuvre is independent of the affected side. The exact effectiveness of this manoeuvre and, in general, of various manoeuvres described for treating the ac-BPPV is unknown, since appropriate series or double-blind controlled studies have not been yet performed (Anagnostou et al., 2015, Casani et al., 2011, Yoon et al., 2005).

Fig. 7.

Yacovino manoeuvre for treating canalolithiasis of the anterior canal (for both, left and right-sided anterior canal BPPV). 1) Patient sitting head straight. 2) The patient is brought backward to the head-hanging position. 3) The head is moved forward “chin to chest”. 4) The patient is returned to the sitting position. Each position is maintained for 30 s.

However, it is advisable to be very cautious when diagnosing an anterior canal BPPV, since it may be difficult to differentiate from central positional vertigo (Bertholon et al., 2002, Büki et al., 2014, Lea et al., 2014, Soto-Varela et al., 2013a). If the therapeutic essays are unsuccessful, a central nervous system disease should be ruled out (von Brevern et al., 2015).

It is not still clear if the anterior canal BPPV is under or overestimated. There are several reports describing downbeat persistent nystagmus, with or without an appreciable torsional component, lasting, in general, more than a minute and frequently without latency (Amor-Dorado et al., 2012, Cambi et al., 2013, JM, 1992; von Brevern et al., 2015; Parnes and Price-Jones, 1993, Squires et al., 2004, Yetiser, 2015). It has been claimed that, related to the anterior canal, cupulolithiasis should be more frequent than canalolithiasis, especially in posttraumatic cases (Dlugaiczyk et al., 2011). But, to date, we cannot state that the cupulolithiasis of the anterior canal has been already documented (von Brevern et al., 2015).

As a corollary, BPPV treatment needs an accurate diagnosis, always based upon the observation of the characteristic nystagmus that points to the affected canal. Some interesting questions regarding BPPV treatment are still vague. Unifying the diagnostic criteria may help to plan accurate research studies leading to clarify the pending questions.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of PLA General Hospital Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery.

References

- Amor-Dorado J.C., Barreira-Fernández M.P., Aran-Gonzalez I., Casariego-Vales E., Llorca J., González-Gay M.A. Particle repositioning maneuver versus Brandt-Daroff exercise for treatment of unilateral idiopathic BPPV of the posterior semicircular canal. Otol. Neurotol. 2012;33:1401–1407. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318268d50a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostou E., K I., Spengos K. Diagnosis and Treatment of anterior-canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a systematic review. J. Clin. Neurol. 2015;11:262–267. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2015.11.3.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostou E., Stamboulis E., Kararizou E. Canal conversion after repositioning procedures: comparison of Semont and Epley maneuver. J. Neurol. 2014;261:866–869. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appiani C.G., Catania G., Gagliardi M., Cuiuli G. Repositioning maneuver for the treatment of the apogeotropic variant of horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol. Neurotol. 2005;26:257–260. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200503000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appiani G.C., Catania G., Gagliardi M. A liberatory maneuver for the treatment of horizontal canal paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol. Neurotol. 2002;22:240–241. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asprella-Libonati G. Lateral canal BPPV with pseudo- spontaneous nystagmus masquerading as vestibular neuritis in acute vertigo: a series of 273 cases. J. Vestib. Res. 2014;24:343–349. doi: 10.3233/VES-140532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asprella-Libonati G. Pseudo-spontaneous nystagmus: a new sign to diagnose the affected side in lateral semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2008;28:73–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asprella-Libonati G.A. Diagnostic and treatment strategy of lateral semicircular canal canalolithiasis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2005;25:277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw S.T., Todd M.J., Aw G.E., McGarvie L.A., Halmagyi G.M. Benign positional nystagmus: a study of its three-dimensional spatio-temporal characteristics. Neurology. 2005;64:1897–1905. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000163545.57134.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babac S., Djeric D., Petrovic-Lazic M., Arsovic N., Mikic A. Why do treatment failure and recurrences of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo occur? Otol. Neurotol. 2014;35:1105–1110. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bela B., Michael E., Heinz J.L.Y. Vitamin D deficiency and benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo. Med. Hypotheses. 2013;80:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholon P., Bronstein A.M., Davies R.A., Rudge P., Thilo K.V. Positional down beating nystagmus in 50 patients: cerebellar disorders and possible anterior semicircular canalithiasis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 2002;72:366–372. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.3.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büki B., Mandalà M., Nuti D. Typical and atypical benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: literature review and new theoretical considerations. J. Vestib. Res. 2014;24:415–423. doi: 10.3233/VES-140535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakir B.O., Ercan I., Cakir Z.A., Turgut S. Efficacy of postural restriction in treating benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:501–505. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambi J., Astore S., Mandalà M., Trabalzini F., N D. Natural course of positional down-beating nystagmus of peripheral origin. J. Neurol. 2013;260:1489–1496. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6815-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casani A.P., Cerchiai N., Dallan I., Sellari-Franceschini S. Anterior canal lithiasis: diagnosis and treatment. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011;144:412–418. doi: 10.1177/0194599810393879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casqueiro J.C., Ayala A., Monedero G. No more postural restrictions in posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol. Neurotol. 2008;29:706–709. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31817d01e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou W.-Y., Lee H.-L., Tsai S.-C., Yu T.-H., Lee X.-X. A single therapy for all subtypes of horizontal canal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1432–1435. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000168092.91251.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.J., Lee J. Bin, Lim H.J., Park H.Y., Park K., In S.M., Oh J.H., Choung Y.-H. Clinical features of recurrent or persistent benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012:1–6. doi: 10.1177/0194599812454642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choung Y.-H., Shin Y.R., Kahng H., Park K., Choi S.J. “Bow and lean test” to determine the affected ear of horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1776–1781. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000231291.44818.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano A., Dispenza F., Citraro L., Petrucci A.G., Di Giovanni P., Kulamarva G., Mathur N., Croce A. Are postural restrictions necessary for management of posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2011;120:460–464. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano A., Dispenza F., Suarez H., Perez-Fernandez N., Manrique-Huarte R., Ban J.H., Kim M.B., Strupp M., Feil K., Oliveira C.A., Sampaio A.L., Araujo M.F.S., Bahmad F., Ganança M.M., Ganança F.F., Dorigueto R., Lee H., Kulamarva G., Mathur N., Di Giovanni P., Petrucci A.G., Staniscia T., Citraro L., Croce A. A multicenter observational study on the role of comorbidities in the recurrent episodes of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2014;41:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaiah A.K., Andreoli S. Postmaneuver restrictions in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010;142:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugaiczyk J., Siebert S., Hecker D.J., Brase C., Schick B. Involvement of the anterior semicircular canal in posttraumatic benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo. Otol. Neurotol. 2011;32:1285–1290. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31822e94d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epley J.M. Human experience with canalith repositioning maneuvers. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;942:179–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epley J.M. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:399–404. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faldon M.E., Bronstein A.M. Head accelerations during particle repositioning manoeuvres. Audiol. Neurootol. 2008;13:345–356. doi: 10.1159/000136153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fife T.D., Iverson D.J., Lempert T., Furman J.M., Baloh R.W., Tusa R.J., Hain T.C., Herdman S., Morrow M.J., Gronseth G.S. Practice parameter: therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008;70:2067–2074. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313378.77444.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster C.A., Zaccaro K., Strong D. Canal conversion and reentry: a risk of Dix–Hallpike during canalith repositioning procedures. Otol. Neurotol. 2012;33:199–203. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31823e274a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrmpas G., Barkoulas E., Haidich A.B., Tsalighopoulos M. Vertigo during the Epley maneuver and success rate in patients with BPPV. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2013;270:2621–2625. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrmpas G., Rachovitsas D., Haidich A.B., Constantinidis J., Triaridis S., Vital V., Tsalighopoulos M. Are postural restrictions after an Epley maneuver unnecessary? First results of a controlled study and review of the literature. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36:637–643. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganança F.F., Simas R., Ganança M.M., Korn G.P., Dorigueto R.S. Is it important to restrict head movement after Epley maneuver? Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71:764–768. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31246-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C.R., Gadoth N. Repeated vs single physical maneuver in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2004;110:166–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helminski J.O. Effectiveness of the canalith repositioning procedure in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Phys. Ther. 2014;94:1373–1382. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helminski J.O., Zee D.S., Janssen I., Hain T.C. Effectiveness of particle repositioning maneuvers in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a systematic review. Phys. Ther. 2010;90:663–678. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma K., Numata T., Mitsuhashi T., Tomemori T., Watanabe R., Okamoto Y. Two types of direction-changing positional nystagmus with neutral points. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011;38:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honrubia V., Baloh R.W., Harris M.R., Jacobson K.M. Paroxysmal positional vertigo syndrome. Am. J. Otol. 1999;20:465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horii A., Kitahara T., Osaki Y., Imai T., Fukuda K., Sakagami M., Inohara H. Intractable benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo: long-term follow-up and inner ear abnormality detected by three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging. Otol. Neurotol. 2010;31:250–255. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181cabd77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House M.G., Honrubia V. Theoretical models for the mechanisms of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Audiol. Neuro-Otol. 2003;8:91–99. doi: 10.1159/000068998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt W.T., Zimmermann E.F., Hilton M.P. Modifications of the Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008675.pub2. CD008675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T., Matsuda K., Takeda N., Uno A., Kitahara T., Horii A., Nishiike S., Inohara H. Light cupula: the pathophysiological basis of persistent geotropic positional nystagmus. BMJ Open. 2014;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006607. e006607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T., Takeda N., Ito M., Sekine K., Sato G., Midoh Y., Nakamae K., Kubo T. 3D analysis of benign positional nystagmus due to cupulolithiasis in posterior semicircular canal. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129:1044–1049. doi: 10.1080/00016480802566303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T., Ito M., Takeda N., Uno A., Marsunaga T., Sekine K., K T. Natural course of the remission of vertigo in patients with benign paroxysmal positional. Neurology. 2005;64:920–921. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152890.00170.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JM E. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:399–404. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.S., Oh S.Y., Lee S.H., Kang J.H., Kim D.U., Jeong S.H., Choi K.D., Moon I.S., Kim B.K., Oh H.J., K H. Randomized clinical trial for apogeotropic horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2012;78:159–166. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823fcd26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.H., Kim M.B., Ban J.H. Persistent geotropic direction-changing positional nystagmus with a null plane: the light cupula. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:15–19. doi: 10.1002/lary.24048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.H., Kim Y.G., Shin J.E., Yang Y.S., Im D. Lateralization of horizontal semicircular canal canalolithiasis and cupulopathy using bow and lean test and head-roll test. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2016;273:3003–3009. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-3894-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.H., Shin J.E., Kim Y.W. A new method for evaluating lateral semicircular canal cupulopathy. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1921–1925. doi: 10.1002/lary.25181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.S., Oh S.Y., Lee S.H., Kang J.H., Kim D.U., Jeong S.H. Randomized clinical trial for geotropic horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2012;78:159–166. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182648b8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisilevsky V., Bailie N.A., Dutt S.N., R J. Lessons learned from the surgical management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: the university health network experience with posterior semicircular. J. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2009;38:212–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korres S., Riga M.G., Xenellis J., Korres G.S., Danielides V. Treatment of the horizontal semicircular canal canalithiasis: pros and cons of the repositioning maneuvers in a clinical study and critical review of the literature. Otol. Neurotol. 2011;32:1302–1308. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31822f0bc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea J., Lechner C., Halmagyi G.M., Welgampola M.S. Not so benign positional vertigo: paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus from a superior cerebellar peduncle neoplasm. Otol. Neurotol. 2014;35:e204–e205. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Bin, Han D.H., Choi S.J., Park K., Park H.Y., Sohn I.K., Choung Y.-H. Efficacy of the “bow and lean test” for the management of horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:2339–2346. doi: 10.1002/lary.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leveque M., Labrousse M., Seidermann L., Chays A. Surgical therapy in intractable benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:693–698. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang W., Zhang A.B., Bai X., Zhang S. Epley and Semont maneuvers for posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a network meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:951–955. doi: 10.1002/lary.25688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias J.D., Ellensohn A., Massingale S., Gerkin R. Vibration with the canalith repositioning maneuver: a prospective randomized study to determine efficacy. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1011–1014. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandalà M., Pepponi E., Santoro G.P., Cambi J., Casani A., Faralli M., Giannoni B., Gufoni M., Marcelli V., Trabalzini F., Vannucchi P., Nuti D. Double-blind randomized trial on the efficacy of the Gufoni maneuver for treatment of lateral canal BPPV. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1782–1786. doi: 10.1002/lary.23918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciano E., Marcelli V. Postural restrictions in labyrintholithiasis. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2002;259:262–265. doi: 10.1007/s00405-001-0445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S.J., Bae S.H., Kim H.D., Kim J.H., Cho Y.B. The effect of postural restrictions in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:408–411. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0836-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogun O.A., Janky K.L., Cohn E.S., Büki B., Lundberg Y.W. Gender-based comorbidity in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H.J., Kim J.S., Han B.I., Lim J.G. Predicting a successful treatment in posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2007;68:1219–1222. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259037.76469.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papacharalampous G.X., Vlastarakos P.V., Kotsis G.P., Davilis D., Manolopoulos L. The role of postural restrictions after BPPV treatment: real effect on successful treatment and BPPV's recurrence rates. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/932847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham K., Leonard G., Feinn R.S., Lafreniere D., Kenny A.M. Prospective clinical investigation of the relationship between idiopathic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and bone turnover: a pilot study. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2834–2839. doi: 10.1002/lary.24162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnes L.S., Price-Jones R.G. Particle repositioning maneuver for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1993;102:325–331. doi: 10.1177/000348949310200501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Vázquez P., Franco Gutiérrez V., Soto-Varela A., Amor-Dorado J.C., Martín-Sanz E., Oliva-Domínguez M., Lopez-Escamez A. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otoneurology committee of Spanish otorhinolaryngology and head and neck surgery society consensus document. Acta Otorrinolaryngol. Esp. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2017.05.001. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez P., Franco V., Cuesta P., Aldama P., Alvarez M.J., Méndez J.C. Recurrence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol. Neurotol. 2012;33:437–443. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182487f78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez P., Franco V., Oliva M., López Escámez J.A. A pilot study using intratympanic methylprednisolone for treatment of persistent posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2016;12:321–325. doi: 10.5152/iao.2016.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riga M., Korres S., Korres G., Danielides V. Apogeotropic variant of lateral semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: is there a correlation between clinical findings, underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms and the effectiveness of repositioning maneuvers? Otol. Neurotol. 2013;34:1155–1164. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318280db3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R.A., Gans R.E., Deboodt J.L., Lister J.J. Treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: necessity of postmaneuver patient restrictions. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2005;366:357–366. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.16.6.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schratzenstaller B., Wagner-Manslau C., Alexiou C., Arnold W., Arnol W. High-resolution three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of the vestibular labyrinth un patients with atypical and intractable benign positional vertigo. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2001;63:165–177. doi: 10.1159/000055734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semont A., Freyss G., Vitte E. Curing the BPPV with a liberatory maneuver. Adv. Otorhinolaryngol. 1988;42:290–293. doi: 10.1159/000416126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C.I., Kang B.C., Yoo M.H., Chung J.W., Yoon T.H., Park H.J. Management of 210 patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: AMC protocol and outcomes. Acta Otolaryngol. 2015;135:422–428. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2014.993089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Varela A., Rossi-Izquierdo M., Sánchez-Sellero I., Santos-Pérez S. Revised criteria for suspicion of non-benign positional vertigo. QJM. 2013;106:317–321. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Varela A., Rossi-Izquierdo M., Santos-Pérez S. Can we predict the efficacy of the semont maneuver in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posterior semicircular canal? Otol. Neurotol. 2011;32:1008–1011. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182267f02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Varela A., Santos-Perez S., Rossi-Izquierdo M., Sanchez-Sellero I. Are the three canals equally susceptible to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Audiol. Neurotol. 2013;18:327–334. doi: 10.1159/000354649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Varela A., Rossi-Izquierdo M., Martínez-Capoccioni G., Labella-Caballero T., Santos-Pérez S. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posterior semicircular canal: efficacy of Santiago treatment protocol, long-term follow up and analysis of recurrence. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2012;126:363–371. doi: 10.1017/S0022215111003495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto Varela A., Bartual Magro J., Santos Pérez S., Vélez Regueiro M., Lechuga García R., Pérez-Carro Ríos A., Caballero L. Benign paroxysmal vertigo: a comparative prospective study of the efficacy of Brandt and Daroff exercises, Semont and Epley maneuver. Rev. Laryngol. Otol. Rhinol. (Bord) 2001;122:179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires T.M., Weidman M.S., Hain T.C., Stone H.A. A mathematical model for top-shelf vertigo: the role of sedimenting otoconia in BPPV. J. Biomech. 2004;37:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenerson R.L., Cronin G.W., Marbach P.M. Effectiveness of treatment techniques in 923 cases of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:226–231. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000154723.55044.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talaat H.S., Abuhadied G., Talaat A.S., Abdelaal M.S.S. Low bone mineral density and vitamin D deficiency in patients with benign positional paroxysmal vertigo. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2014;272:2249–2253. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talaat H.S., Kabel A-M.H., Khaliel L.H., Abuhadied G., El-Naga H.A.E-R.A., Talaat A.S. Reduction of recurrence rate of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo by treatment of severe vitamin D deficiency. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016;43:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirelli G., Russolo M. 360-degree canalith repositioning procedure for the horizontal canal. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Brevern M., Bertholon P., Brandt T., Fife T., Imai T., Nuti D., Newman-Toker D. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: diagnostic criteria. J. Vestib. Res. 2015;25:105–117. doi: 10.3233/VES-150553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Brevern M., Radtke A., Lezius F., Feldmann M., Ziese T., Lempert T., Neuhauser H. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 2007;78:710–715. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacovino D.A., Hain T.C., Gualtieri F. New therapeutic maneuver for anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J. Neurol. 2009;256:1851–1855. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yetiser S. A new variant of posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo : a nonampullary or common crus canalolithiasis. Case Rep. Otolaryngol. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/816081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yetiser S., Ince D. Diagnostic role of head-bending and lying-down tests in lateral canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol. Neurotol. 2015;36:1231–1237. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon K.K., Jeong E.S., Jong W.C. The effect of canalith repositioning for anterior semicircular canal canalithiasis. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2005;67:56–60. doi: 10.1159/000084336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucca G., Valli S., Valli P., Perin P., Mira E. Why do benign paroxysmal positional vertigo episodes recover spontaneously? J. Vest. Res. 1998;8:325–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]